#Luís Miguel Cintra

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Abraham’s Valley (1993) | dir. Manoel de Oliveira

#abraham's valley#vale abraão#manoel de oliveira#cécile sanz de alba#leonor silveira#luís miguel cintra#films#movies#cinematography#scenery#screencaps

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

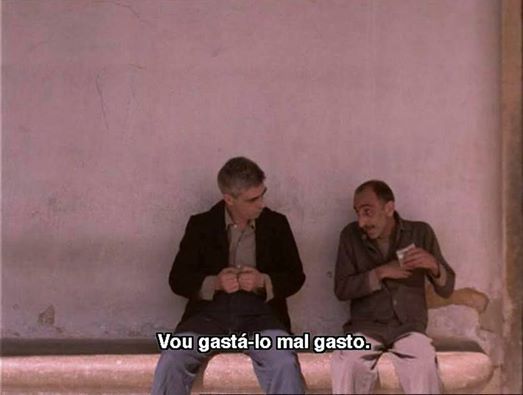

A Divina Comédia [The Divine Comedy] (Manoel De Oliveira, 1991)

#A Divina Comédia#drama film#Portugal#cinema português#Manoel de Oliveira#Maria de Medeiros#allegory#Dostoevsky#The Brothers Karamazov#Miguel Guilherme#Luís Miguel Cintra#experimental movie#Mário Viegas#Leonor Silveira#Nietzsche#La divina commedia#Diogo Dória#Paulo Matos#Ruy Furtado#José Wallenstein#José Régio#morality#religion#philosophy#European cinema#bible#ethics#Adam and Eve#atheism#cinema de Portugal

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Silvestre (1981) de João César Monteiro

#silvestre (1981)#joão césar monteiro#maria de medeiros#luís miguel cintra#cinema português#portuguese cinema#european cinema#medieval fantasy#screencaps#film still#cinematography

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

MANOEL DE OLIVEIRA: A CAREER by Richard Peña

Chances are that within a few years Portuguese director Manoel de Oliveira will be the first filmmaker in history to celebrate his own centenary with the release of a brand-new film. Having just turned 96 (at the time of this writing), and showing no signs of slowing down, the remarkably vigorous Oliveira, who could easily pass for a man 20 years younger, is brimming with plans and ideas for the future. Yet Oliveira's longevity is really just a footnote on what already is one of the extraordinary bodies of work in film history.

Born in 1908 in Oporto, the son of a successful and innovative industrialist, Oliveira developed a passion for cinema early, influenced at first especially by the work of Griffith, Stroheim and the French avant-garde. He recalls the tremendous impact Dreyer's JEANNE D'ARC had on him, as well as the first Soviet montage films screened in Portugal. Joining in with a group of like-minded enthusiasts, Oliveira attempted to make a film about Portugal's involvement in World War One-the first of many projects throughout his career that he would be forced to abandon. After gaining some practical experience working with Italian director Rino Lupo on a film about the Virgin of Fatima, Oliveira in 1931-at the age of 23-completed his first film, the half-hour HARD LABOR ON THE RIVER DOURO. A portrait of a river that geographically defines Oporto, as well as of the workers who make their livings along its bank, the film demonstrates Oliveira's familiarity with the "city symphony" genre that by then was a staple of avant-garde work. Here as in so much of his later work Oliveira's approach to editing is essentially musical, more focused on creating rhythms and movements than establishing temporal or spatial relationships.

Throughout the 1930's, Oliveira mainly worked in the family's business, helping supervise his father's factories when he wasn't driving race cars (another early passion) or, occasionally, making short films on subjects ranging from baroque sculpture to the Portuguese automotive industry. In 1941, he began work on what would become his first feature, ANIKI-BOBO. A quietly powerful look at children's games, and their relationship to adult behavior, ANIKI-BOBO was shot almost entirely in real locations using natural light sources. Two professional actors headed the cast, but the rest of his players were kids recruited off the streets. Widely criticized when released-the Salazar dictatorship was in full swing-the film was also a failure at the box office, but today is commonly cited as a kind of precursor to the neo-realist style that would sweep across Italy and then the rest of Europe in just a few years.

Discouraged, and by then a husband and father, Oliveira again devoted himself primarily to his family business endeavors, partially satisfying his artistic urges by working on scripts that he would only share with a small circle of friends. In the mid-1950's, intrigued by the possibilities of color, he embarked on his next film, THE PAINTER AND THE CITY, a stunning visual essay on his friend, the Oporto painter Antonio Cruz. The film was well received and was even shown in o number of international film festivals. A commission from the government enabled him to make

BREAD (1959), a brilliantly edited, Vertov-like study of the Portuguese baking industry.

THE PASSION OF CHRIST (1963) brought Oliveira to the small town of Curalha, in the remote Tras-os-Montes region of northeast Portugal. Each year, its inhabitants re-enact the passion and death of Christ—a common enough spectacle throughout Europe, yet here Oliveira masterfully shows how the experience of putting on and then performing the actual play affects its players throughout the rest of the year. In a decade known for various experiments in mixing documentary with fic-tion, Oliveira's THE PASSION OF CHRIST is surely one of the most remarkable, patiently revealing the complex interpersonal relationships and tensions that lay just below the surface of the spectacle.

In 1971, Oliveira turned 63, and he finally released his second feature, THE PAST AND THE PRESENT. All of Oliveira's work up to this point had had its basis in the documentary, in the encounter or confrontation of the camera with the physical world; beginning with this film, his work would shift 180 degrees and focus almost obsessively on notions of theatricality, on artifice and convention. Based on Vicente Sanchez's play, THE PAST AND THE PRESENT is a deceptively light (but actually quite brutal) dissection of upper-class morality; it was followed relatively quickly (for Oliveira) with his third feature, and one of his best, BENILDE OR THE VIRGIN MOTHER (1973). Adapted from a play by his friend Jose Regio, BENILDE deals with a case of "hysterical pregnancy" that increasingly takes on religious overtones; Oliveira refuses to "open up" the play, as is so often done in screen adaptations of theatrical works, but rather uses his camera to explore the limits of the theatrical.

If Oliveira had stopped filming after ANIKI-BOBO, he most probably would have deserved a generous footnote in film history; if he had stopped after BENILDE, that note might have been expanded to a paragraph or two, lamenting the director's great but unfulfilled potential. With his next film, however, Oliveira leapt into the first ranks of contemporary directors. Commissioned by Portuguese television, and originally broadcast in six episodes, DOOMED LOVE (1978) tells the story of two young lovers, Teresa and Simao, whose families oppose their union. Here, Oliveira perfects the style he had been developing since returning to fiction: shots are very long and generally static; his actors, facing frontally, deliver their lines often with a minimum of inflection; the sets make little or no attempt at verisimilitude. And yet, by emphasizing the artifice, by highlighting conventions of speech and movement, Oliveira manages to create a purer expression of the red-hot emotions that lay at the heart of Castelo Branco's classic novel.

This strange artifact from what had been an almost unknown only just thrown off the shackles of dictatorship a few years before landed like a UFO on the international festival circuit in the late 1970's, and after producing equal amounts of bafflement and amazement, became one of the most talked about films of the time. DOOMED LOVE would have been a tough act for anyone to follow, but Oliveira came through with the film that for many critics remains his masterpiece. FRANCISCA (1981) is based on a novel by Agustina Bessa Luis, another of Oliveira's favorites, that deals with an incident in the life of Castelo Branco, the author of DOOMED LOVE. In love with Fanny, a young English girl, he is despondent when she chooses his friend Jose Augusto instead. Yet after marriage, Jose Augusto refuses to have anything to do with her, and she dies a virgin. Critics had already written about Oliveira's "trilogy of frustrated loves," noting the thematic similarities between THE PAST AND THE PRESENT, BENILDE and DOOMED LOVE; with FRANCISCA one could now speak of a "tetralogy," as the film deepened Oliveira's treatment of that theme as well as moved even further into his "theatricalized" cinematic style.

With the relative box office success and critical acclaim of DOOMED LOVE and FRANCISCA, Oliveira could finally look forward to a "normal" career as a director-only of course he was now in his mid-70s. Happily, his age proved no limitation on his output, and over the next two decades he would direct sixteen additional features, a number of shorts, and a masterful seven-hour screen adaptation of Claudel's THE SATIN SLIPPER (1985). He would also begin work on a feature for which he is shooting several minutes a year that will be released only after his death.

Oliveira's filmmaking style has continued to evolve; the rigidly formal theatricality of his 70's and early 80's features has given way to more conventional styles of staging action. He has also had the chance to work with some of cinema's finest actors-Marcello Mastroianni, Catherine Deneuve, Irene Papas, Michel Piccoli, John Malkovich, etc.—so his work with actors has become more naturalistic. Yet there is rarely any mistaking a film by Manoel de Oliveira for one by anyone else. There has continued to be in his work a fascination with the process of A Talking Picture (2003) adaptation: what happens to a text, something Oliveira regards as inherently unstable, when it is "fixed" on the screen? There is an extraordinary economy of gesture in his work, as he seems almost painfully aware how each cut, camera movement or framing will affect the text. Another recurring feature of Oliveira's work is his sense of narrative rhythm; as noted earlier, his approach to montage has much less to do with the demands of storytelling then they do with his attention to rhythm, tone and movement. Shots and even sequences are often repeated, held what might seem to be too long or glimpsed only briefly.

A TALKING PICTURE (2003) exemplifies much of what is best and most distinctive in Oliveira's work. The film examines the interaction of history and myth, and the interaction of both with the monuments, buildings and places in the world around us. A kind of guided tour of the Mediterranean basin given by a history professor to her young daughter, their journey becomes a kind of modern odyssey, reversed in direction and now an attempt to re-join the husband instead of the wife. On their journey, they are joined by three famous actresses-Catherine Deneuve, Irene Papas, Stefania Sandrelli — each in their way linked to the sites of civilization visited along the way. As each is also depicted as a kind of legend in her own right, the actresses take on a kind of mythic quality, the contemporary version of goddesses or muses or some other supernatural deities. Their halting dialog, caused at least partially by their often being asked to speak languages with which they don't feel entirely comfortable, makes them seem as if at times they're actually quoting, another aspect of their otherworldliness.

Oliveira weaves a dense, provocative allegory here, with the education of the child seen as a complex mix of both the world and the ideas that have shaped it over time. Yet, lurking in the background is humanity's capacity for negation, for a violence and destructiveness that all the works of civilization visited on the journey here have tried to tame or at least control. The final image of the film, in a sense, says it all: Malkovich's, and our, confrontation with the darkest corner of the human psyche.

It's a stunning and harrowing moment, and one that only Oliveira could have pulled off.

— Richard Peña, Program Director, Film Society of Lincoln Center Associate Professor, Film Studies, Columbia University

A Talking Picture (2003) Kino Video 333 West 39th Street NY, NY 10018 www.kino.com

#Manoel de Oliveira#Leonor Silveira#Filipa de Almeida#John Malkovich#Catherine Deneuve#Stefania Sandrelli#Irene Papas#Luís Miguel Cintra#Michel Lubrano di Sbaraglione#François Da Silva#Nikos Hatzopoulos#António Ferraiolo#Alparslan Salt#Ricardo Trêpa#David Cardoso#Júlia Buisel#Kino Video#Richard Peña#Um Filme Falado#A Talking Picture

1 note

·

View note

Text

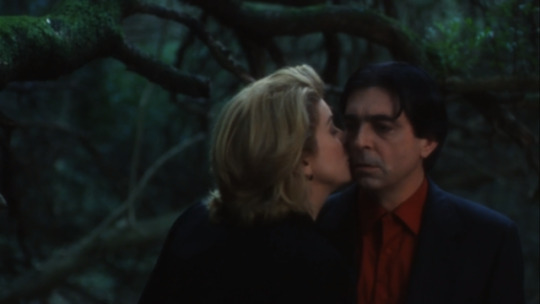

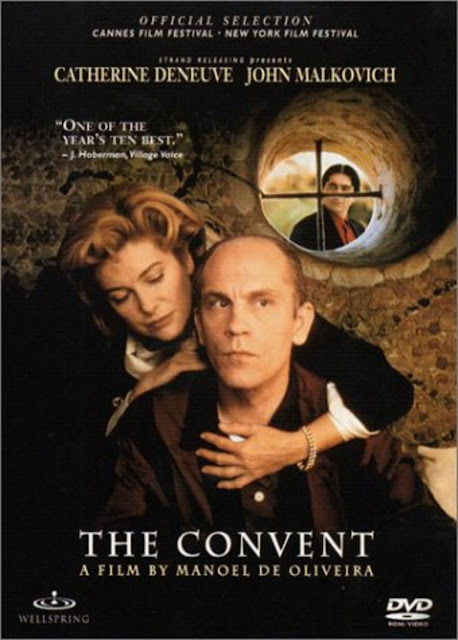

O convento [Manoel de Oliveira, 1995]

#cine#cine portugués#cine francés#Manoel de Oliveira#Agustina Bessa-Luís#Catherine Deneuve#Luis Miguel Cintra

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

SILVESTRE João César Monteiro, 1981

#Luís Miguel Cintra#teresa madruga#maria de medeiros#portuguese cinema#portuguese movies#portuguese film#cinema#movies#great cinematography#film#Jorge Silva Mel#João César Monteiro#silvestre

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Convent (Manoel de Oliveira, 1995)

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mário Bonito 1OO anos | 23.09-31.12 2021

01.10: [mesa redonda + filme] Consciência Crítica - homenagem a Mário Bonito, Cinemateca Portuguesa - Museu do Cinema, Lisboa

“Arte sem o humano, apenas será indústria, tal como cinema sem arte será apenas técnica”1.

O estudo do cinema de autor e a participação ativa na sua divulgação e compreensão é campo experimental que permite a Mário Bonito ensaiar conceitos e interpretações que constituem os alicerces da sua arquitetura, como expressão cultural e forma de arte, consolidando o seu entendimento sobre a importância do processo criativo e do papel da arte na sua dimensão social e expressão de forma culta e universal na personificação do progresso, como fator de transformação.

Em 1956, por ocasião da exibição de “La Pueblerina: um filho que não pedi” (1949), de Emilio Fernández, no Cineclube de Espinho, Mário Bonito escreve uma palestra que é reprovada pela comissão de censura.

A abordagem ao cinema de Emílio Fernandez possibilita a Mário Bonito apresentar e desenvolver temas interditos que condicionam a evolução da própria sociedade portuguesa, recorrendo a uma citação dos arquitetos P. L. Weiner e J. L. Sert para expressar a veracidade dos registos e correspondente ética artística do realizador mexicano: “o cinema não foi senão um meio de exteriorizar os mais prementes problemas de uma maioria desfavorecida e miserável, «ainda enraizada na velha cultura sobrevivente às leis rígidas da era colonial e às repressões periódicas»”2.

Associando-se à celebração dos 100 anos de Mário Bonito, a 1 de outubro, a Cinemateca Portuguesa – Museu do Cinema recebe, às 18h00, mesa-redonda sobre as várias facetas do trabalho de Mário Bonito e projeta, às 19:30, o filme “La Pueblerina: um filho que não pedi”.

Na mesa-redonda estarão reunidos os amigos de Mário Bonito: Luís Miguel Cintra e Jorge de Silva Melo, fundadores do Teatro da Cornucópia (1973), e Rui Mendes, ator, encenador e antigo estudante de arquitetura colaborador de Mário Bonito. Com eles estarão, também, Mário Gabriel Bonito e Mário Sérgio Bonito.

Durante a sessão será dada a conhecer a palestra censurada de Mário Bonito.

1. Bonito, Mário, “O que é um Cine-clube”, Catálogo de inauguração de Cine-Clube de Guimarães, maio/julho 1958.

2. “Notas sobre a história e a vida social no Mexico” por P. L. Wiener e J. L. Sert, in L’architecture d´Aujourd´hui, janeiro 1951.

www.mariobonito100anos.com

Organização: Matéria. conferências brancas em parceria com Cinemateca Portuguesa – Museu do Cinema.

0 notes

Photo

FILME O Convento de Manoel de Oliveira Elenco Catherine Deneuve (Hélène), John Malkovich (Michael), Luís Miguel Cintra (Baltar), Leonor Silveira (Piedade), Duarte de Almeida (Baltazar), Heloísa Miranda (Berta), Gilberto Gonçalves (pescador) Realização Manoel de Oliveira Produção Madragoa Filmes, La Sept (França), Gemini Films; Autoria Manoel de Oliveira baseado na obra "As Terras do Risco" de Agustina Bessa-Luís Música Igor Stravinsky, Toshirô Mayuzumi, Sofiya Gubaidulina; Ano 1995; Duração 91 minutos; Género Drama; Classificação M/12 SINOPSE O Convento Filme de Manoel de Oliveira, com Catherine Deneuve e John Malkovich, baseado na obra "As Terras do Risco" de Agustina Bessa-Luís O investigador norte-americano Michael Padovic está a trabalhar numa tese que se destina a provar que Shakespeare, o expoente máximo da dramaturgia britânica, era, afinal de ascendência espanhola, mas faltam-lhe alguns documentos essenciais, que julga estarem nos arquivos do antiquíssimo Convento da Arrábida, em Portugal. Acompanhado pela mulher, Hélène, viaja de Paris até à Arrábida, onde se instalam. O seu anfitrião é o guardião do convento, Baltar, uma estranha personagem que fica de imediato cativado por Hélène. Para distrair a atenção de Padovic, Baltar sugere ao professor que contrate a nova arquivista do convento, Piedade, como sua assistente. Hélène anda ressentida por ver o marido mais interessado pelas pesquisas do que por ela. A presença da jovem e bonita Piedade agrava ainda mais a situação e tanto serve para as manipulações do diabólico Baltar como completa os hábeis enredos de Hélène. Os acontecimentos vão-se tornando cada vez mais bizarros até que culminam de forma inesperada. Manoel de Oliveira filma esta busca de uma tese sobre o dramaturgo William Shakespeare na Arrábida, intitulada "O Convento". https://cinecartaz.publico.pt/Filme/18262_o-convento Exteriores Convento da Arrábida LINK https://youtu.be/Il4j_0R1doE OPINIÃO ARGHHHHhhhhhhhhhhhhh detestei. Secaaaaaaaaaaaa 20220727 Entretenimento,Filme,Opinião,Diário, #LopesCa #LopesCaOpiniaoFilme #Entretenimento #Filme #Cinema #Opinião #Diário http://lopesca.blogspot.com/2022/09/filme-o-convento-de-manoel-de-oliveira.html ►Like/Gosta◄ https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=468982011907167&set=a.143408627797842&type=3

0 notes

Text

Abraham's Valley (1993) | dir. Manoel de Oliveira

#abraham's valley#vale abraão#manoel de oliveira#cécile danz de alba#leonor silveira#luís miguel cintra#films#movies#cinematography#scenery#screencaps

85 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Divina Comédia [The Divine Comedy] (Manoel De Oliveira, 1991)

#A Divina Comédia#drama film#Portugal#cinema português#Manoel de Oliveira#Maria de Medeiros#allegory#Dostoevsky#The Brothers Karamazov#Miguel Guilherme#Luís Miguel Cintra#experimental movie#Mário Viegas#Leonor Silveira#Nietzsche#La divina commedia#Diogo Dória#Paulo Matos#Ruy Furtado#José Wallenstein#José Régio#morality#religion#philosophy#European cinema#bible#ethics#Adam and Eve#atheism#cinema de Portugal

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Doutoramento Honoris Causa de Jorge Silva Melo e Luís Miguel Cintra

Doutoramento Honoris Causa de Jorge Silva Melo e Luís Miguel Cintra

A Universidade de Lisboa, sob proposta da Faculdade de Letras , vai atribuir o grau de Doutor Honoris Causa a Jorge Silva Melo e Luís Miguel Cintra. Publicado inicialmente em https://ift.tt/3dTqLTY

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Open Call: "Entre Linhas, Tela e Palco"

Os Caminhos do Cinema Português celebram a sua XXX edição com a exposição “Entre Linhas, Tela e Palco”. Em parceria com o KOLETIVOK, lançamos esta Open Call convidando artistas visuais a submeterem obras que dialoguem com a filmografia de Luís Miguel Cintra. Procuramos ilustrações, poéticas visuais ou colagens que explorem a interseção entre o cinema e as artes visuais, celebrando o legado deste…

#ArteECinema#ArteVisual#ArtistasPorgueses#CaminhosDoCinemaPortuguês#CinemaPortuguês#coimbra#CulturaPortuguesa#EntreLinhasTelaPalco#ExposiçãoDeArte#FestivalDeCinema#ilustração#KOLETIVOK#LuísMiguelCintra#OpenCall#tagv

0 notes

Photo

SILVESTRE João César Monteiro, 1981

#Luís Miguel Cintra#teresa madruga#maria de medeiros#portuguese cinema#portuguese movies#portuguese film#cinema#movies#great cinematography#film#Jorge Silva Mel#João César Monteiro#silvestre

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Convent (Manoel de Oliveira, 1995)

5 notes

·

View notes