#London Consultant Psychiatrist

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Last month, England and Wales took the first step towards legalising assisted dying (a separate bill is under consideration in Scotland, while Northern Ireland is described as “left behind” on the issue). After a five hour debate in Parliament, MPs voted by 330 to 275 in favour of the The Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill. As it stands, the bill would allow terminally ill adults with an expected six months left to live to end their own lives. They would have to make two separate declarations, signed by either themselves or a proxy (who can be someone who has known them for two years or someone of “good standing” in the community), and their eligibility would have to be confirmed by two doctors and a High Court judge.

The vote to approve this bill is being presented by supporters of the right to assisted death as a victory for dignity, compassion and bodily autonomy. The ultimate in the right to choose. And on these bases you might assume that I am one of those people. After all, I do believe in bodily autonomy. I hope it goes without saying that I believe in dignity and compassion in death as in life. And, of course, I believe fervently in the right to choose what happens to your own body.

But rather than these beliefs leading me to support this bill, they are in fact the reason that I have my doubts. Let me explain.

Like most good liberals, when I historically thought at all about assisted dying I considered myself to be in favour of it — although admittedly without having thought through any of the details. There is no doubt whatsoever that current end of life care leaves far too many people suffering a painful and undignified end. There is also no doubt that some people, out of fear of such an end, have ended their lives earlier than they might otherwise have chosen to, while they still had the ability to travel to Dignitas in Switzerland. Family members have faced the choice of letting their loved one travel and die alone in a foreign country, or to go with them and face the risk of prosecution on their return. None of this is humane. And legalising assisted dying seems like an obvious way to address these issues. That, in any case, was what I historically thought.

But a few years ago, doubts were introduced in my mind when I was a judge on the Royal Society of Literature’s Christopher Bland Prize. One of the books submitted to us was a memoir by Alastair Santhouse, a consultant neuropsychiatrist at The Maudsley Hospital in London. The book, Head First: A Psychiatrist’s Stories of Mind and Body, didn’t make the shortlist in the end, but it did make a lasting impact on me, most notably on my opinion of assisted dying.

Santhouse opens his section on the topic by recounting his first experience of a practice he was later to discover was so common it had a name: “granny dumping.” That is, the depositing of an unwanted elderly relative (the name suggests usually a female relative — we’ll come back to this) at a hospital over Christmas. The elderly woman in question here was brought in by her son and daughter-in-law who told Santhouse, “She just isn't right,” before leaving and turning off their phones. On her own, the woman, now in tears, told Santhouse there was nothing wrong with her. “They just don’t want me over Christmas.”

This episode may shock you as it did me. The thought of doing such a thing to my own mother causes me physical pain in my stomach and a lump in my throat. I simply cannot bear it. But, says Santhouse, the medical profession quickly disabused him of his “notions of people always behaving honourably or having respect for the elderly.” And it is his decades of experience, his repeated witnessing of this lack of honour and respect for older people, that makes him so implacably opposed to assisted dying.

While some may have taken a calm and rational choice to end their lives, there are an unquantifiable number of people who may be pressured or coerced into doing so. […] As they approach the end of their lives, people feeling unwell and scared can experience a pressure, spoken or implied, to let their families collect the inheritance that they would otherwise not get if they had to pay for medical or nursing home fees. They may also feel a pressure to release their families from the burden of caring for them. Vulnerable, frightened patients may only feel loved, accepted and valued by their families if they take the decision to end their lives by assisted suicide. — Santhouse (2021) pp. 206-7

As my parents have aged I too have witnessed some of this lack of honour and respect for older people in action. For example the time an impatient male carer made my strong, capable, fiercely independent mother cry when she was, in the immediate aftermath of a hip operation, feeling none of those things. I have also seen how quickly someone who is strong, capable and fiercely independent can suddenly become scared, uncertain and vulnerable when they lose their independence, even if, as with my mother, it was only temporary. It is far from unbelievable that someone in this state could be quite easily coerced into agreeing to end their own life. Rather, it is frighteningly believable. Indeed I personally know of at least one case where someone felt pressured (to my knowledge never overtly vocalised, but as Santhouse points out, this pressure does not need to be spoken to be felt) into arranging their own death, before at the last minute changing their mind. How many others have simply gone through with it?

Well, according to a recent report on assisted dying, “mercy killings” and failed suicide pacts, that is a question for which we do not have an answer and nor are we likely to get one any time soon. Written by the think-tank “The Other Half, the “Safeguarding women in assisted dying” report notes the “secrecy” that is “built into the latest assisted dying proposals in the UK.”

This is also true of countries thought to be exemplars like Oregon and the Australian states. In Oregon, death certificates do not include a note of assisted dying. All provider information on assisted deaths is deleted after the annual report is prepared. This simple data report does not, and would not, reveal the kind of abuses we fear here. In Canada, there are stories now emerging of families who have tried to prevent their relative being given MAID [medical assistance in dying] —as they believe they are not terminally ill. Families cannot get access to medical records to understand if their relative was coerced. The state protects itself and those who are involved in delivering death. — The Other Half (2024)

The abuse the authors of this report in particular fear is state-delivered domestic homicide — and not without good reason. Although the UK inexplicably only started including over 75s in domestic abuse statistics in 2020, we know that elder abuse is far from uncommon. We also know that women live more years than men in ill health, and that having a disability doubles a woman’s risk of being domestically abused. The law in England and Wales has also recently recognised suicide as an outcome of domestic abuse (indeed, data suggests it may be more common even than homicide) and has outlawed the “rough sex defence” through which men who killed their sexual partner via strangulation achieved leniency in prosecution and sentencing.

We cannot claim therefore to be ignorant of the clear vulnerabilities women face, nor of capacity of violent men to exploit the law to justify their abuse. And yet despite this knowledge, the potential for these laws to be used in the furtherance of violence against women has been shamefully absent from the assisted dying debate.

And not just here in Britain. The report highlights that most countries that have legalised assisted dying don’t even consider domestic abuse in their safeguards (which are mostly concerned with will beneficiaries), let alone collect or publish any data on the issue. Meanwhile, assisted dying campaigners in the UK have championed two male mercy killers with a history of domestic violence, one of whom had previously been imprisoned for bludgeoning his second wife with a mallet.

The result of this data gap on domestic abuse and assisted dying is that it’s hard to quantify exactly how widespread the problem is. We do have some indications, however. We know that in Canada, women “seem 2 times more likely to seek MAID track 2—which allows for those with non ‘reasonably foreseeable’ deaths to die” — that is, women who are not terminally ill. We know in Belgium that women dominate the figures of those given “psychiatric euthanasia.” Why are these psychologically troubled women so much more likely to seek death than their male counterparts? The data is silent on this issue, and the states in question seem in no hurry to uncover the reason behind the sex discrepancy.

In the Bill as it currently stands in England and Wales, assisted death for the mentally unwell would not be an immediate issue, since the law would apply only to terminally ill patients — but the example of countries that have gone before us shows how easily and quickly the concept of “terminal illness” can be and has been stretched.

…it is estimated that now 3 per cent of Belgian and Dutch assisted deaths are for psychiatric disorder. Psychiatric illness is not usually terminal and suicidal impulses are often part of the illness itself. To have a state-sanctioned way for such people to end their lives should be a cause of concern for everyone.

One study showed that 50 per cent of Dutch psychiatric patients asking to die had a personality disorder* (a very unstable diagnosis with symptoms sensitive to social pressures), a figure similar to that in Belgium. Twenty per cent had never been hospitalized because of mental health problems (which calls into question how severe they are) and, in 56 per cent of cases, loneliness and social isolation was thought to be an important factor. This in turn raises the question as to whether assisted suicide is being used instead of proper social and mental health care. Perhaps the most troubling statistic in the study was that in 12 per cent of cases in the Netherlands, the three assessors had not agreed unanimously on the decision, and yet the assisted death went ahead anyway. — Santhouse (2021) p. 209

This final statistic is echoed in a finding from The Other Half report, which notes that in Western Australia, guidance states that “feeling a burden” is meant to be a red flag for assessors determining a patient’s eligibility. But despite “more than a third of those approved reporting they felt a burden, Western Australian medics decided that everyone who applied for VAD was eligible in acting voluntarily and not being subject to coercion in 2023-24.” Which, to say the least, stretches credulity; as the authors of the report put it: “It is startling that despite the prevalence of domestic and elder abuse in Australia, the assisted dying safeguards for these picked up absolutely no one at all.”

Well, quite.

Santhouse also raises concerns about safeguarding, noting that “as the experienced expert who would be asked to undertake [safeguarding] assessments,” their presence is “no reassurance whatsoever.” It is, he writes, “extremely difficult to truly know someone's motives, including the motives in someone asking for assisted dying. This is particularly the case where the individual concerned is frightened, vulnerable or wants to please others, and do what they believe others want them to do.”

Source: The Other Half (2024)

[Image description: an excerpt from The Other Half, "The 2006 killing of Mandy Horne in Shetland was widely reported as a Romeo and Juliet, mercy killing by her husband - Mandy had MS. Both died so there was no investigation. Only through Mandy's father and a curious Times journalist was it later revealed to be a very violent murder and suicide by Mandy's husband: he's also killed their pets. The night before she died, Mandy had asked friends to stay because she was scared of her husband."]

But despite the failure of states that have legalised assisted dying to collect data on its intersection with domestic violence, we are not entirely without pertinent evidence. By combing through “news reporting, inquest findings, sentencing remarks and court of appeal judgements where killings and attempted killings were said by a judge, coroner or defence to be part of a mercy killing, or (failed) suicide pact,” The Other Half report authors have identified and reviewed more than 100 “mercy killings” and “failed suicide pacts” — and they make for sobering reading.

The Other Half’s research revealed that “at least 5 UK men per year violently kill women who are disabled, elderly or infirm, under the guise of mercy killings.” Eighty-eight per cent of the killers were male, overwhelmingly husbands and sons, and the killings were extremely violent, involving “cutting women’s throats, bludgeoning them, shooting them, or using stabbing, suffocation and strangulation.” One woman was thrown off a balcony by her son. Another was strangled with her dressing-gown cord by her husband. Many women had their throat slit. “Overkill,” the authors found, was frequent. Meanwhile, men are “overwhelmingly the survivors of ‘failed suicide pacts’.”

Having my throat slit, or being strangled with my dressing gown cord, or being thrown off a balcony does not sound particularly merciful to me, and whether or not you wish to die, it is hard to imagine anyone choosing to die in such a violent manner. But the vast majority of these women did not ever express a wish to die at all, let alone to die violently. 78% of them were not even terminally ill, being simply “disabled or elderly and infirm.” The report identified an increase in a woman’s care needs as a trigger for a mercy killing.

The majority of these men were let off with suspended sentences and sympathy from judges who repeatedly spoke of the “exceptional” nature of these strikingly similar cases (the report found that the few women who engage in “mercy killing” generally get a life sentence), with “very limited data, if any, data [being] collected by the state on these deaths, and no learning or curiosity.” One man let off with a suspended sentence had written the joint suicide note himself with no input from his wife; another had a history of domestic violence against his dead wife. And, let’s not forget, these lenient sentences all took place in a context where assisted dying is illegal. It’s also worth pointing out that this analysis would not have been possible if these mercy killings had taken place under the auspices of the new bill, because none of the information would be publicly available.

Source: The Other Half (2024)

[Image description: excerpt from The Other Half, The judicial safeguard: even criminal court judges are not able to spot patterns in so called mercy killings. Selected judicial remarks to mercy and failed suicide pact killers. "This is indeed an exceptional case" - Scotland husband smothered wife who'd returned home from hospital. "A tragedy for you...exceptional in the experiences of this court. You were under immense emotional pressure...you acted out of love." - Husband wrote his wife's suicide note then cut her throat. Suspended sentence. "I conclude the mental torment engendered by the impossible situation in which you found yourself must have been intolerable." - Husband strangled wife after she had broken her vertebrae and had been unable to look after him. Suspended sentence. "[The judge] decided to suspend the sentence due to the 'exceptional' circumstances" - Father helped his daughter take an overdose then suffocated her. She had been receiving (poor) inpatient mental health care in hospital. Suspended sentence. "It was, in part, an act which you believed to be one of mercy." - Husband knocked his wife out with a dumbbell then slit her throat. She had dementia. Suspended sentence. "the defendant was not coping with the strain of being the principle carer...I accept at the time he did believe he was doing what he believed to be an act of mercy." - Husband smothered wife with clingfilm. She had Parkinsons and had recently has a fall. Suspended sentence. "the case was exceptional and jail would not be appropriate" -Husband gave his wife an overdose of antidepressants and suffocated her in a plastic bag. "I accept in killing your wife you were doing so because you felt this was the only way to limit or prevent her suffering." - Husband pushed his wife down the stairs and then strangled her. She had dementia. Suspended sentence. "The taking of a life is always a grave crime, but the exceptional circumstances of this case require the court to show compassion." - Husband cut his wife's throat after her dementia worsened. Suspended sentence. "indeed true love...an exceptional case" - Husband attempted to bludgeon his wife to death with a hammer. Suspended sentence. "a most unusual and very sad case" - Husband struck his wife with an iron pole, then smothered her as she sat in bed. Suspended sentence. "You were convinced that she was suffering and it was more than you could bear." - Son threw his mother off a balcony as she was receiving end of life care. Suspended sentence.]

But what about all the people who are not coerced, you may be thinking at this point. Don’t they have a right to bodily autonomy? Don’t they have the right to choose?

To this I have two points, the first of which is that rights in a democracy must be balanced and the right of one person to willingly choose to end his life must be weighed against the right of another person to choose to continue with hers. Nothing about the debate so far, nor the bill in question, makes me at all confident that this balance has even been considered, much less achieved. As Sarah Ditum noted in her excellent piece in The Times, published shortly before the vote took place:

But for legislation that relies on the principle of informed consent, there seems to be a strange haste to get it on the books without fully investigating its implications. The full text of the bill was published last Tuesday; MPs will vote on its second reading less than two weeks from today. This is not ideal, particularly when the issue is as consequential, ethically and practically, as medically administered death.[…] Before taking a neutral stance on a bill, the government should scrutinise it, including producing an impact assessment and a legal issues memorandum. These are supposed to be made available one month before the second reading, but as they don’t currently exist and the second reading is less than a month away anyway, that isn’t going to happen. — Ditum (2024)

Beyond this lack of proper scrutiny is the question of whether the state of care for those living with illness, whether terminal or not, gives people a meaningful choice to make. Certainly, the Health Secretary Wes Streeting doesn’t think it does, leading to his voting against the bill. Neither, apparently, does the Voluntary Assisted Dying (VAD) programme in Australia, if the pamphlet cited by The Other Half is anything to go by, featuring as it does this family quote: “The voluntary assisted dying process was really the first time that any medical and allied health practitioners had given such understanding and empathy to my sister's suffering, and that was such a relief.”

And, sure, you could read this as approbation of the VAD programme. Or you could read it as an indictment on the care system.

For his part, Santhouse says his experience is that when people are asking to die, “they are commonly communicating something different.”

They are asking for help to live. They are saying that they can't see how they can cope with the problems that they have, and are asking for help in finding a way through the seemingly impossible difficulties that lie ahead. To take their request at face value, and to whisk them over to the nearest assisted dying clinic, is to abrogate our responsibilities to the patient. — Santhouse (2024), p.210

If people are not making a free choice, if people are choosing death not because they want to die but because we have failed so abjectly to make living bearable for those who need care, what does that say about us as a society?

Similarly, as the Other Half notes in its examination of female suicidality in response to domestic violence, it “is impossible not to imagine a scenario that a woman in abusive situations would find it easier to access NHS assisted dying than support to create new life away from her abuser.” Certainly, assisting her death would be cheaper, a concern which was also raised by Santhouse, who fears that legalising assisted dying would make it “far easier to give up on people once the going gets tough.”

Advocates for assisted dying often rebut concerns about the morality or ethics of assisted dying by pointing to the strong public support that their position holds. And it’s true: my opinion is, as they say, unpopular: a poll conducted by Opinium earlier this year on behalf of pressure group Dignity in Dying found that 75% of the British public supports assisted dying.

But how many of the British public really understand the implications of how this works in practice? How many of them are thinking about the violence of the mercy killings we are asked to sympathise with, or the ease with which vulnerable people can be coerced into unwillingly ending their own lives? I ask, because when you poll British people who are more likely to have a good grasp of how assisted dying might work out in reality, the support drops rather precipitously.

A recent survey by the British Medical Association found that 50% of doctors were in favour of the legalisation of assisted dying, which is already a substantial drop from the position of the general public. The difference was even more pronounced when considering only palliative care doctors, that is, the doctors who are most likely to have direct experience of the realities for the patients involved (how good care can change their attitude to life; how vulnerable to coercion patients might be). Among these doctors, 76% were against a change in the law — almost the exact inverse of the opinion of the general public.

Where we go from here is unclear. The Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill is now at the committee stage, where it will hopefully receive some of the scrutiny that has to date been sorely lacking —although given parliamentary timetabling restrictions this is by no means guaranteed. In the meantime, social and palliative care continues to be underfunded and under-resourced. And some men will continue to violently kill some women, and the state will continue to allow most of them to get away with it.

In a weird coincidence, shortly after I wrote this piece a friend of mine told me about the Christmas care package that had been sent by Age UK to her mother and aunt:

[Image description: A collection of gifts that includes slippers, a blanket, shortbread biscuits, a box of Celebrations chocolates, other unidentifiable edible or wearable treats.]

Age UK apparently sends these packages out to people on benefits with age-related health problems, and it’s such a brilliantly practical and caring idea I was inspired to set up a monthly donation to the charity.

Here’s why you should too: ageing is a feminist issue. Older women are poorer (thanks to the pay and pensions gap) and more frail and in poorer health (thanks to the health data and treatment gap) than older men. They are also more likely, thanks to sex differences in unpaid care (see Invisible Women for stats on this), to have spent their life taking care of other people. So, this Christmas, instead of “granny dumping,” let’s return the favour and make sure older women are taken care of themselves as they have taken care of all of us.

The link to donate again is here.

#disablility#feminism#invisible women#right to die laws#assisted dying#trigger warning#violence against women#violence against disabled women#domestic abuse

412 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black Wings at Midnight

Shyly sharing my first Hannibal fanfic: a reimagining of Seasons 1-3 set during World War II in Britain. It comes complete with vintage-style illustrations and links to suggested listening (ranging from Handel to 1940s' swing).

See below for the summary, and under the cut for an extract.

When former detective Will Graham is pulled away from his intelligence work at Bletchley Park in 1942, to consult on a hauntingly familiar crime scene, he feels alive for the first time in years. But when his life begins falling apart, he finds himself thrown into a complex dance of trust and suspicion with the man assigned to help him: an aristocratic Lithuanian flying ace and peacetime psychiatrist, whose intentions are anything but clear…

If you do decide to give it a read, I hope you enjoy it, and would love it if you took the time to leave a comment. Hearing people's expectations and thoughts as they read has been the most enjoyable part of sharing this online. Thank you all, and sending hugs from London.

From Black Wings at Midnight: Chapter 3

‘May I come in?’

The voice is deep, with a warm lilt of an Eastern European accent. Crawford’s eyes brighten and he rises from the desk with what Will considers unseemly haste.

‘Aha! Now here’s a familiar face. Come in, come in, old chap. Pull up a chair. This is Will Graham, who I mentioned on the phone. Brilliant mind. Brilliant.’

Will scowls at the praise and turns in his chair, prepared to be combative. He has no great love for the airmen of the RAF. They are nothing more than overgrown public schoolboys, with their chummy nicknames and their maverick flair. In their presence, Will feels his carapace stripped away, exposed as an awkward provincial with a clumsy accent, a different breed from these sauntering gods of the sky.

The newcomer does little to dispel his prejudices. The flattering RAF uniform makes most men look good, but this fellow seems to have stepped straight out of an advertisement. J.C. Leyendecker in the flesh, Will thinks bitterly, feeling short, and dark, and rustic.

Nothing about this man is rustic: dark blond hair parted with almost surgical precision; a broad chest and shoulders beneath the blazon of the RAF wings; trousers ironed to crisp perfection; tie perfectly centred. Everything about him screams money, from the scent of his cologne to the small gold signet ring just visible on his little finger.

After spending long hours digging into the minds of the Nazi commanders, Will can’t resist a snort. Good God, how they would love you!

Light brown eyes linger on Will for a moment, already looking amused.

‘Good afternoon, Mr Graham. I apologise for interrupting your colloquy, but Jack is an old friend. I was delighted to hear he was visiting us. May I?’ He gestures to the unused chair before the desk and Will raises a shoulder minutely, neither inviting nor repelling. He settles for glaring across at Jack. He doesn’t wish to spend any longer here than necessary, and he certainly doesn’t want to play third wheel to some back-slapping reunion.

‘Will,’ says Jack, ‘this is Flight Lieutenant Hannibal Lecter – or should I say Dr Lecter?’ The two men exchange a twinkle of camaraderie and Will stifles a desire to stab the table with his pencil. ‘We met before the war,’ Jack continues. ‘Dr Lecter has a private psychiatry practice on Harley Street, and helped us with a profile for the Bethnal Green Killer in ’38.’

Will remembers the case. It wasn’t long after he’d been signed off, still gathering together the shreds of himself in the nursing home. He allows himself a glance sideways.

‘Strange to swap the comforts of Harley Street for a wet field in Hampshire, Dr Lecter. Get tired of listening to rich old ladies?’

‘I “got” patriotic,’ Lecter says gently. ‘My country was invaded last year. Lithuania,’ he adds, for Will’s benefit. ‘I have not lived there for many years, but old affections still linger: a sense of duty, if you will. I learned to fly when I was younger’ – Of course you did, thinks Will bitterly – ‘so why not put my skills in the service of my adopted country?’

‘And he’s become quite the terror,’ Jack says cheerfully. ‘Give him a Spitfire and he’s absolutely fearless. They say Göring’s offered a bounty to anyone who brings him down.’ He dismisses Lecter’s gesture of modest denial and turns back to Will. ‘When I heard he was stationed here, I thought it’d be helpful to have his thoughts – and his support too, of course.’

‘Convenient,’ Will says under his breath, studying his fingers. He feels Lecter’s eyes lingering on him with something that’s uncomfortably close to satisfaction. For a moment he entertains himself, wondering whether he loathes fighter aces more or less than psychiatrists. It comes out as a balance. The airmen are more irritating, but he has bitter personal experience of his own with psychiatry.

‘Come now, Jack,’ Lecter says, ‘you are not being completely honest with Mr Graham.’ He leans a little closer, offering Will a lungful of his expensive cologne, and his voice drops, as though this is a secret to be shared between them. ‘Jack has asked me to have a few conversations with you before you start on this case. Just to help prepare your armour for the field of battle, as it were.’

Will’s eyes snap up to Jack Crawford, who has the grace to look embarrassed.

‘Will, I’ve read your files. It’s my job to make sure you’re fit for duty. I want to help you in any way I can.’

‘I don’t find it helpful to be covertly psychoanalysed!’

‘This is not psychoanalysis,’ Lecter says placidly into the awkward silence, ‘merely a common interest. You have nothing to fear, Mr Graham. Besides,’ he adds, straightening his cuffs, ‘I am not a psychoanalyst. Freud may have some interesting principles, and Jung has made many valuable insights into my field, but I do not ride under their banner. Biological psychiatry is very different from asking you to tell me your dreams.’ Dark eyes dart up and catch Will’s just as he makes the mistake of looking up. Something coils in the pit of his stomach. ‘Though I have no doubt your dreams must be a fascinating place.’ …

‘Just a conversation,’ Will hears himself say.

‘But of course.’ Lecter shrugs in a Gallic fashion. ‘And we can give dear Jack a good night’s sleep. Just a conversation or two among friends.’

‘Associates,’ Will snaps back. Lecter laughs as if he has said something delightful.

‘God forbid we should become friendly. Come with me to the mess, Mr Graham. Let’s get some tea.’

Will feels wrong-footed. He wants to prod; to offend; to get under Lecter’s skin and force him to feel even the faintest echo of Will’s crippling discomfort. He feels like a parcel passed from Jack to Lecter, a fragile curiosity to be wrapped in cotton wool and discussed in lowered voices. He feels lonely and patronised, and because, to his deep-seated disgust, he finds himself wanting Lecter to like him, Will lashes out.

‘I doubt we’ll be friends, Dr Lecter. I don’t find you that interesting.’

A hand falls on his shoulder. To Jack, frowning in his chair, it’ll look comradely, a way to show that no offence has been taken. To Will, the touch is unsettling: part warning, conveyed through the grip of fingers far stronger than he’d anticipated; and part protective caress. I don’t, Will repeats doggedly in his head, find you interesting.

‘Ah,’ Lecter says softly in his ear, ‘but you will.’

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Hadley Freeman

Date: Feb 11, 2023

It wasn’t easy for Hannah Barnes to get her book published. As the investigations producer for Newsnight and a long-term analytical and documentary journalist, she is used to covering knotty stories and this particular one, she knew better than most, was complex. She had been covering the Gender Identity Development Service (Gids), based at the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust in north London — the only one of its kind for children in England and Wales — since 2019 and decided to write a book about it. “I wanted to write a definitive record of what happened because there needs to be one,” she tells me. Not everyone agreed. “None of the big publishing houses would take it,” she says. “Interestingly, there were no negative responses to the proposal. They just said, ‘We couldn’t get it past our junior members of staff.’ ”

Whatever their objections were, they could not have been about the quality of Barnes’s book — Time to Think: The Inside Story of the Collapse of the Tavistock’s Gender Service for Children is a deeply reported, scrupulously non-judgmental account of the collapse of the NHS service, based on hundreds of hours of interviews with former clinicians and patients. It is also a jaw-dropping insight into failure: failure of leadership, of child safeguarding and of the NHS. When describing the scale of potential medical failings, the clinicians make comparisons with the doping of East German athletes in the 1960s and 1970s and the Mid Staffs scandal of the 2000s, in which up to 1,200 patients died due to poor care. Other insiders discuss it in reference to the Rochdale child abuse scandal, in which people’s inaction led to so many children being so grievously let down.

Gids treats children and young people who express confusion — or dysphoria — about their gender identity, meaning they don’t believe their biological sex reflects who they are. Since the service was nationally commissioned by the NHS in 2009 it has treated thousands of children, helping many of them to gain access to gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, known as “puberty blockers”, originally formulated to treat prostate cancer and to castrate male sex offenders, and also used to treat endometriosis and fertility issues. The service will shut this spring, following a deeply critical interim report in February 2022 by Dr Hilary Cass, a highly respected paediatrician who was hired by NHS England to look into the service. Dr Cass concluded that “a fundamentally different service model is needed”.

Gids should be an easy story to tell: many people have been trying to blow the whistle for a long time, but Anna Hutchinson, a clinical psychologist who used to work at the Tavistock Centre, told Barnes that those who spoke up were “always driven out one way or another”.

“It is really not normal for mental health professionals to talk to journalists as openly as they talked to me, and that shows how desperate they were to get the story out,” Barnes says. The clinicians struggled to be heard, just as Barnes later struggled to get her book out; some people prefer censorship to the truth if the latter conflicts with their ideology. And yet, concerns about the service had been in plain sight for years: in February 2019, a 54-page report compiled by Dr David Bell, then a consultant psychiatrist at the trust and the staff governor, was leaked to The Sunday Times. Dr Bell said Gids was providing “woefully inadequate” care to its patients and that its own staff had “ethical concerns” about some of the service’s practices, such as giving “highly disturbed and distressed” children access to puberty blockers. Gids, he concluded, “is not fit for purpose”. Many of Bell’s concerns had been expressed 13 years earlier in a 2006 report on Gids completed by Dr David Taylor — then the trust’s medical director — who described the long-term effects of puberty blockers as “untested and unresearched”.

“Taylor’s recommendations were largely ignored,” Barnes writes, and, in the decade and a half between Taylor and Bell’s reports, Gids would refer more than 1,000 children for puberty blockers, some as young as nine years old. It’s impossible to obtain a precise figure because neither the service nor the endocrinologists who prescribe the blockers could or would provide them to people who have asked for them, including Barnes. One figure they have given is that between 2014 and 2018, 302 children aged 14 or under were referred for blockers. It is generally accepted now that puberty blockers affect bone density, and potentially cognitive and sexual development. “Everything was there — everything. But the lessons were never learnt,” Barnes says.

Because this story touches on gender identity — one of the most sensitive subjects of our era — it has been difficult to get past the ideological battles to see the truth. Was the service helping children become their true selves, as its defenders contended? Or was it pathologising and medicalising unhappy kids and teenagers, as others alleged?

This reflects the fraught, partisan ways people see gender dysphoria: is it akin to being gay and therefore something to be celebrated?; or is it an expression of self-loathing, like an eating disorder, requiring therapeutic intervention? This has led to the current confusion over whether the planned conversion therapy ban should include gender as well as sexuality. “Conversion therapy” obviously sounds terrible, and politicians across the spectrum — from Crispin Blunt on the right to Nadia Whittome on the left — have loudly voiced their support for the inclusion of gender on the bill, which would thereby suggest that therapy for gender dysphoria is analogous to trying to “cure” someone of homosexuality.

But many clinicians argue that including gender would potentially criminalise psychotherapists exploring with their patients the reason for their confusion; after all, a doctor wouldn’t simply validate a bulimic’s desire to be thin — they’d try to find the cause of their inner discomfort and help them learn to love their body. Gids itself has long been conflicted about this complex issue. Dr Taylor wrote in 2005 that staff didn’t agree among themselves about what they were seeing in their patients: “were they treating children distressed because they were trans,” Barnes writes in Time to Think, “or children who identified as trans because they were distressed?”

How did the country’s only NHS clinic for gender dysphoric children not even understand what they were doing, and yet keep doing it? Thanks to Barnes and her book, we now know the answers to those questions, and many more.

Gids was founded in 1989 by Domenico Di Ceglie, an Italian child psychiatrist. His aim was to create a place where young people could talk about their gender identity with “non-judgmental acceptance”. Puberty blockers were available for 16-years-olds who wanted to “pause time” before committing themselves — or not — to gender-changing surgery. (Gids never offered that surgery, which is illegal in England for those under the age of 17, but it did refer patients to the endocrinology clinic, which provided the blockers. Blockers stop the body going through puberty, thereby making it easier — in some ways — for a person later to undergo the surgery.) In 1994 the service became part of the Tavistock and Portman NHS Trust, which was known for its focus on talking therapies. By the early 2000s those working within Gids noted that certain gender activist groups — such as Mermaids, which supports “gender-diverse” kids and their families — were exerting an “astonishing” amount of influence on Gids, especially in regard to encouraging the prescribing of puberty blockers. Barnes writes in her book that Sue Evans, a nurse who worked at Gids at the time, asked a senior manager why Gids couldn’t just focus on talking therapy and not give out body-altering drugs. According to her and another clinician, Barnes writes, the senior manager replied, “It’s because we have this treatment here that people come.”

In around the year 2000, the trust asked Di Ceglie to draw up a report of who its patients were. The results were astonishing. Most of Gids’s patients were boys with an average age of 11. More than 25 per cent of them had spent time in care, 38 per cent came from families with mental health problems and 42 per cent had lost at least one parent, either through separation or death. Most had histories of other problems such as anxiety and physical abuse; almost a quarter had a history of self-harm. No conclusions were drawn and Gids continued to treat gender dysphoria as a cause, rather than a symptom, of adolescent distress.

It was a gender identity clinic in the Netherlands in the late Nineties that came up with the idea of giving blockers to children under 16, and in doing so furnished Gids with the justification it needed. The Dutch clinic said that 12-year-olds could be put on blockers if they had suffered from long-term gender dysphoria, were psychologically stable and in a supportive environment. This was known as the “Dutch protocol”. Pressure groups and some gender specialists encouraged the clinic to follow suit.

Dr Polly Carmichael took over as Gids’s director in 2009 and, in 2011, the service undertook an “early intervention study” to look at the effect of blockers on under-16s, because so little was known about their impact on children. Instead of waiting for the study results, Gids eliminated all age limits on blockers in 2014, letting kids as young as nine access them. At the same time referrals were rocketing, meaning clinicians had less time to assess patients before helping them access blockers. In 2009 Gids had 97 referrals. By 2020 there were 2,500, with a further 4,600 on the waiting list, and clinicians were desperately overstretched. “As the numbers seeking Gids’s help exploded around 2015, there was increased pressure to get through them. In some cases that meant shorter, less thorough assessments. Some clinicians have said there was pressure on them to refer children for blockers because it would free up space to see more children on the waiting list,” Barnes says.

Clinicians were seeing increasingly mentally unwell kids, including those who didn’t just identify as a different gender but as a different nationality and race: “Usually east Asian, Japanese, Korean, that sort of thing,” Dr Matt Bristow, a former Gids clinician, tells Barnes. But this was seen by Gids as irrelevant to their gender identity issues. Past histories of sexual abuse were also ignored: “[A natal girl] who’s being abused by a male, I think a question to ask is whether there’s some relationship between identifying as male and feeling safe,” Bristow says. But, clinicians point out, any concerns raised with their superiors always got the same response: that the kids should be put on the blockers unless they specifically said they didn’t want them. And few kids said that. As one clinician told Barnes: “If a young person is distressed and the only thing that’s offered to them is puberty blockers, they’ll take it, because who would go away with nothing?”

Then there was the number of autistic and same-sex-attracted kids attending the clinic, saying that they were transgender. Less than 2 per cent of children in the UK are thought to have an autism spectrum disorder; at Gids, however, more than a third of their referrals had moderate to severe autistic traits. “Some staff feared they could be unnecessarily medicating autistic children,” Barnes writes.

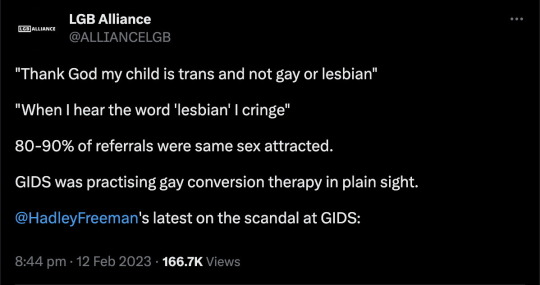

There were similar fears about gay children. Clinicians recall multiple instances of young people who had suffered homophobic bullying at school or at home, and then identified as trans. According to the clinician Anastassis Spiliadis, “so many times” a family would say, “Thank God my child is trans and not gay or lesbian.” Girls said, “When I hear the word ‘lesbian’ I cringe,” and boys talked to doctors about their disgust at being attracted to other boys. When Gids asked adolescents referred to the service in 2012 about their sexuality, more than 90 per cent of females and 80 per cent of males said they were same-sex attracted or bisexual. Bristow came to believe that Gids was performing “conversion therapy for gay kids” and there was a bleak joke on the team that there would be “no gay people left at the rate Gids was going”. When gay clinicians such as Bristow voiced their concerns to those in charge, they say it was implied that they were not objective because they were gay and therefore “too close” to the work. (Gids does not accept this claim.)

What if becoming trans is — for some people — a way of converting out of being gay? If a boy is attracted to other boys but feels shame about it, then a potential way around that is for him to identify as a girl and therefore insist he’s heterosexual. This possibility complicates the government’s plan — which has cross-party support — for including gender alongside sexuality in the bill to ban conversion therapy, if enabling a young person to change gender is, in itself, sometimes a form of conversion therapy.

I ask Barnes what she thinks and she answers with characteristic caution: “It’s a bit surprising that the NHS has commissioned one of the most experienced paediatricians in the country to undertake what appears to be an incredibly thorough review of this whole area of care, and not wait until she makes those final recommendations before legislating,” she says, weighing every word. (Dr Hilary Cass’s final review is due later this year.)

The sex ratio was also changing to a remarkable degree. When Di Ceglie started his gender clinic, the vast majority of his patients were boys with an average age of 11, and many had suffered from gender distress for years. By 2019-20, girls outnumbered boys at Gids by six to one in some age groups, especially between the ages of 12 to 14, and most hadn’t suffered from gender dysphoria until after the onset of puberty.

Some said this was simply because teenage girls felt more free to be open about their dysphoria. Some clinicians suspected there were other reasons. The clinicians Anna Hutchinson and Melissa Midgen worked at Gids and, after they left, wrotea joint article in 2020 citing a number of potential other factors: the increased “pinkification” and later “pornification” of girlhood; fear of sex and sexuality; social media; collapsing mental health services for adolescents, and so on. “It is important to acknowledge that girls and young women have long recruited their bodies as ways of expressing misery and self-hatred,” Hutchinson and Midgen wrote. And yet Gids’s response was to send these girls to endocrinology for puberty blockers.

The clinicians knew their patients were nothing like those in the Dutch protocol. The latter had been heavily screened, suffered from gender dysphoria since childhood and were psychologically stable with no other mental health issues. “Gids — according to almost every clinician I have spoken to — was referring people under 16 for puberty blockers who did not meet those conditions,” Barnes writes. The majority of children aged 11 to 15 referred to the clinic between 2010 and 2013 were put on blockers. The clinicians tried to reassure themselves by saying the blockers were just giving their patients time to think about what they wanted. They might even alleviate their distress. But in 2016 Gids’s research team presented the initial findings from its early intervention study, which looked at the effect of prescribing blockers to those under 16: although the children said they were “highly satisfied” with their treatment, their mental health and gender-related distress had stayed the same or worsened. And every single one of them had gone on to cross-sex hormones — synthetic testosterone for those born female, oestrogen for natal males. Far from giving them time to think, blockers seemed to put them on a pathway towards surgery. Clinicians were concerned that the service had abandoned NHS best practice. They repeatedly raised this with Carmichael and the executive team, but nothing changed. In just six months in 2018, 11 people who worked at Gids left due to ethical concerns. People who spoke up, such as David Bell and Sonia Appleby, the children’s safeguarding lead for the Tavistock trust, say they were bullied or dismissed. Appleby later won an employment tribunal case against the trust. Bell has said the trust threatened him with disciplinary action in connection with his activities as a whistleblower. He later retired.

Everything the whistleblowers tried to say has been borne out. A 2020 Care Quality Commission inspection of Gids rated the service “inadequate”, and pointed out that some assessments for puberty blockers consisted of only “two or three sessions” and that some staff “felt unable to raise concerns without fear of retribution”. Around the same time, the former Gids patient Keira Bell instigated a judicial review against the trust, arguing that at 16 she had been too young to understand the repercussions of being put on blockers, and that she bitterly regretted her transition. The High Court found in her favour that children are unable to give informed consent to puberty blockers. The Court of Appeal later overturned their verdict on the grounds that it should be up to doctors and not the court to determine competence to consent, but the damage was done: thanks to Bell’s case, it was now public knowledge how shambolic the service had become, unable to provide any data on, for example, how many children with autism they had put on blockers.

So what actually happened at Gids? And why did no one stop it? Barnes’s book suggests multiple credible factors. Activist groups from outside, such as Mermaids and Gendered Intelligence, came to exert undue influence on the service and would complain if they felt things weren’t being done their way. For example, Gendered Intelligence complained to Carmichael, the Gids director, when a clinician dared to express the view publicly that not all children with gender dysphoria would grow up to be transgender. In 2016 an expert in gender reassignment surgery warned Gids that putting young boys on puberty blockers made it more difficult for them to undergo surgery as adults, because their penis hadn’t developed enough for surgeons to construct female genitalia. Instead, surgeons had to use “segments of the bowel” to create a “neo-vagina”. But senior managers rejected calls from its clinicians to put this on a leaflet for patients and families. In the book, Hutchinson is quoted as saying, “I may be wrong, but I think Polly [Carmichael] was afraid of writing things down in case they got into Mermaids’s hands.”

Susie Green was at this point the chief executive of Mermaids and had taken her son, who had been on puberty blockers, to Thailand for gender reassignment surgery on his 16th birthday. In an interview, which is still on YouTube, Green laughingly recalls the difficulties surgeons had in constructing a vagina out of her child’s prepubescent penis. Green stepped down from Mermaids last year.

Money is suspected to have been another issue. When Gids became part of the Tavistock trust, it was such a minor player it wasn’t even in the main building. But by 2020-21, gender services accounted for about a quarter of the trust’s income. David Bell says this allowed the trust to be “blinkered”. The children and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) possibly had similar blinkers. They were so overstretched it appears they were happy to offload as many kids as possible onto Gids, and then disregard what was actually happening there.

“It’s really striking how few people were willing to question Gids. As one clinician said to me, because it was dealing with gender, there was this ‘cloak of mystery’ around it. There was a sense of ‘Oh, it’s about gender, so we can’t ask the same questions that we would of any other part of the NHS. Such as: is it safe? Where’s the evidence? Where’s the data? And are we listening to people raising concerns?’ These are basic questions that are vital to providing the best care,” Barnes says.

And then there was the outside culture. Basic safeguarding failures at Gids seem to have accelerated from 2014 onwards, at the same time that there was a push for the rights of transgender people. Stonewall, having helped to secure equal marriage, had now turned its sights on the rights of trans people. Susie Green, at Mermaids, gave a TED talk that suggested taking her teenage son for a sex change operation was a parenting template to admire. Meanwhile, the TV networks weighed in. In 2014 CBBC aired a documentary, I Am Leo, about a 13-year-old female on puberty blockers who identifies as a boy — mainly, it seems, because of an abhorrence of dresses and long hair. In 2018 ITV showed the three-part drama Butterfly, about an 11-year-old boy whose desire to be a girl is expressed as a desire to wear dresses and make-up. Susie Green was the lead consultant on the show.

David Bell suggests that the Tavistock trust protected Gids “because they saw it as a way of showing that we weren’t crusty old conservatives; that we were up with the game and cutting-edge”. That the Tavistock clinic was briefly, in the 1930s, a place where homosexual men were brought to be “cured” probably also played a part in the trust’s embrace of gender ideology, as if it were an atonement for a past wrong.

As per Dr Cass’s suggestions, Gids will shut this spring and be replaced with regional hubs, where young people will be seen by doctors with multiple specialties. The obsession with gender, and the ensuing lack of intellectual curiosity at Gids about factors that might contribute to a person’s distress and sense of their identity will, hopefully, be gone.

On the one hand, it feels incredible that such a disaster happened. How did an NHS service medicalise so many autistic and same-sex-attracted young people, unhappy teenage girls and children who simply felt uncomfortable with masculine or feminine templates, with so little knowledge of the causes of their distress or the effects of the medicine? And how did Carmichael, still the director of Gids, suffer no repercussions, whereas those who tried to blow the whistle say they were bullied out of their jobs? On the other hand, it is a miracle that the information is now out. For too long, too many people have turned a blind eye to problems arising from gender ideology, including healthcare for gender dysphoric children — because they have been focused on trying to be on the right side of history, they refused to look at the glaring wrongs.

Barnes knows that some will be angry at her for having written the book. But she also knows that she had to write it: “There’s been this idea that the kind of treatment young people got at Gids — physical interventions — is safe treatment for all gender-distressed children,” she says. “But even among the clinicians working on the front line of this issue, there is no consensus about the best way to care for these kids. There needs to be debate about this, and it needs to come out of the clinic and into society, because this isn’t just about trans people — it’s bigger than that. It’s about children.”

[ Via: https://archive.is/Fv41w ]

==

Modern-day Lysenkoism.

#LGB Alliance#Hadley Freeman#Hannah Barnes#Tavistock#GIDS#genderwang#gender ideology#queer theory#ideological capture#ideological corruption#medical scandal#medical malpractice#medical transition#medical corruption#gay conversion therapy#gay conversion#gender dysphoria#dysphoria#puberty#puberty blockers#hormone blockers#homophobia#anti gay#woke activism#wokeness as religion#cult of woke#woke#wokeism#trans the gay away#trans away the gay

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Barbiturates could be bought almost as easily as sweets on the London streets, Mr Ian Milne, the St Pancras Coroner, said yesterday, when he found that Mrs Reginald Kray, aged 23, had killed herself with an ‘enormous dose’ of phenobarbitone.

Mrs Kray, who was referred to by her maiden name of Frances Elsie Shea during the inquest, was the wife of one of the Kray twins. She was found dead at the home of her brother last week.

Mr Frank Brian Shea, of Wimbourne Court, Wimbourne Street, Hackney, E., told the Coroner that his sister had reverted to her maiden name when she went to live with him and his wife of three months before. She had hoped for a reconciliation with her husband.

Dr Julian Silverstone, consultant psychiatrist at Hackney Hospital, said Mrs Kray began psychiatric treatment in 1965. She was admitted to hospital in June 1966, and remained there until September the same year. He agreed with the Coroner that she had had a ‘personality disorder.’ Dr Silverstone said that in October last year she was admitted to St Leonard’s Hospital after an overdose of barbiturates. In January she was again admitted after being found in a gas-filled room. On the second occasion barbiturate poisoning was diagnosed.

Mrs Kray was married at Bethnal Green in April, 1965, soon after the Kray twins were acquitted at the Central Criminal Court of charges of demanding protection money from a Soho club owner.

Mr Reginald Kray was in court at the inquest, but did not give evidence.”

The Times, 1967

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

9th November 2024.

𝐓𝐡𝐮𝐫𝐬𝐝𝐚𝐲 𝟗𝐭𝐡 𝐍𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐦𝐛𝐞𝐫 𝟏𝟗𝟕𝟖. Maurice Dale of Lena’s fan club, took photographs of her at Andy and Carmen Grudko’s parents house in Whitton, Near Twickenham.

𝐅𝐫𝐢𝐝𝐚𝐲 𝟗𝐭𝐡 𝐍𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐦𝐛𝐞𝐫 𝟏𝟗𝟕𝟗. Somewhere South Of Macon was released as a promotional record by Galaxy Records.

𝐓𝐮𝐞𝐬𝐝𝐚𝐲 𝟗𝐭𝐡 𝐍𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐦𝐛𝐞𝐫 𝟏𝟗𝟖𝟐. In the Glasgow Herald, Dorothy Solomon denied that Lena had been ‘Slave Driven’ to complete her TV series by the BBC.

Many BBC employees would disagree with her.

𝐓𝐮𝐞𝐬𝐝𝐚𝐲 𝟗𝐭𝐡 𝐍𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐦𝐛𝐞𝐫 𝟏𝟗𝟖𝟐. The Times reported that Lena was suffering from Anorexia Nervosa.

𝐓𝐮𝐞𝐬𝐝𝐚𝐲 𝟗𝐭𝐡 𝐍𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐦𝐛𝐞𝐫 𝟏𝟗𝟖𝟐. The Daily Star reported that Lena had been bribed to lose weight by the Solomons.

𝐓𝐮𝐞𝐬𝐝𝐚𝐲 𝟗𝐭𝐡 𝐍𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐦𝐛𝐞𝐫 𝟏𝟗𝟖𝟐. The Edinburgh Evening News printed an update from All Saints Hospital.

𝐒𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐚𝐲 𝟗𝐭𝐡 𝐍𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐦𝐛𝐞𝐫 𝟐𝟎𝟎𝟐. The Aberdeen Evening Express looked back 20 years to 1982 when Lena was in hospital with anorexia.

𝐓𝐮𝐞𝐬𝐝𝐚𝐲 𝟗𝐭𝐡 𝐍𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐦𝐛𝐞𝐫 𝟐𝟎𝟎𝟒. The Daily Mirror ran a story about rich and famous people shoplifting.

Byline: TONY BONNICI

THEY are rich, famous and fabulously successful - but certain celebrities aren't averse to a five-finger discount when they're out shopping.

This week, Coronation Street star Jimmi Harkishin was arrested after staff at Brent Cross shopping centre in North West London accused him of swapping price tags on clothes. Jimmi, 45, who - ironically - plays shopkeeper Dev Alahan, accepted a police caution for suspicion of theft by deception. He told his bosses at Granada TV that the allegations were "complete rubbish".

Jimmi is not the first star to run into trouble when nipping down the shops. And a consultant psychiatrist says some celebrities may do it in a desperate attempt to communicate.

Dr Neil Brener, of the Priory Hospital North London, explains: "People who are in the limelight all the time may find they have no other way to communicate.

"In 80 per cent of cases they will carry on stealing until they are caught. Then they will not shoplift again.

"Unlike a true kleptomaniac, people who steal because of emotional problems are fairly common. And it is rarely, if ever, thrill-seeking for its own sake."

Here are some more light- fingered stars who fell foul of the long arm of the law.

WINONA RYDER

THE Mermaids star was fined, put on probation and ordered to do community service after shoplifting from a Beverly Hills store in December 2001.

The elfin-faced actress, who earned up to pounds 4million a film, cut off anti-theft tags and stole 20 items worth pounds 3,000 from Saks, including clothes, hair accessories and a handbag.

She claimed she was preparing for a movie role, but in an interview a few years earlier she had revealed that as a teenager she was caught stealing a comic book and taken home to her parents by police.

HEDY LAMARR

THE 40s Hollywood sex siren was long past her prime when she was caught stealing from a Florida chemist.

The six-times-married star, who died in 2000, was 76 when she was accused of taking eyedrops and laxatives worth pounds 12.

Charges were dropped after she promised not to break any laws for a year. Her lawyer claimed it was simply "absent-mindedness".

In 1965 she was arrested in Los Angeles for stealing a pair of gold slippers. She was cleared, but the publicity is said to have cost her a movie part in Picture Mommy Dead.

TRACY SHAW

THE troubled Coronation Street star claimed she had a secret compulsion brought on by a slimming disease that drove her to steal from shops.

The actress was 22 when she was stopped by Safeways staff for walking out with a 99p punnet of strawberries. She put it down to anorexia and added: "To this day I don't know why I did it."

The star, who earned pounds 50,000 a year playing crimper Maxine, had already been banned from her local Co-op in Belper, Derbys, for stealing fruit and cereals and once admitted going on shoplifting jaunts as a youngster, often getting arrested.

JENNIFER CAPRIATI

THE millionaire tennis ace narrowly escaped prosecution for allegedly taking a pounds 20 ring.

She was 17 when she was held with a friend after trying to walk out of a Florida shopping mall with it on her finger. She claimed she forgot to take it off. Store owners decided not to press charges.

STUART HALL

FOOTBALL commentator Hall has never denied taking a jar of coffee and a packet of sausages, worth pounds 3.94, from his local Safeways in 1991. But he was cleared by a jury after explaining how he had suffered a series of personal disasters and could not remember taking the items.

A collection of clocks he and his father had restored had been stolen, he was facing financial ruin as a result of being a Lloyds Name and the BBC had just ended his TV contract.

He said: "When you are faced with the loss of everything, you don't think about what you're doing half the time. I had no recollection of taking those things."

LADY ISOBEL BARNETT

THE popular TV panellist committed suicide in 1980 after being fined over a can of tuna and a carton of cream.

The 62-year-old - a star of What's My Line? and Twenty Questions - stole them from her village grocer. Four days after the case she took an overdose of painkillers.

Shortly before her death she admitted to an interviewer that she was a compulsive thief.

OLGA KORBUT

OLYMPIC gymnastics phenomenon Olga was charged in 2002 with shoplifting pounds 10 worth of groceries in Atlanta, Georgia.

She said it was a misunderstanding and she had been going to the car to get her purse.

She avoided prosecution for the theft of the items - including cheese, tea and chocolate syrup - by agreeing to take a course on "values" and stay away from the store.

LENA ZAVARONI

THE tragic former child star was accused of stealing a 50p packet of jelly from her local supermarket in 1999.

She shot to fame as a little girl after appearing on Opportunity Knocks but saw her career destroyed by anorexia nervosa and was living on benefits.

The charge was dropped, but a few months later she died after a radical operation which she hoped would cure her.

STEVE STRANGE

NEW Romantic Strange, real name Steven Harrington, was given a three-month suspended prison sentence after stealing a pounds 10.99 Tellytubby doll.

He was already on bail for stealing a woman's jacket from Marks & Spencer in Cardiff.

Defending him, Mel Butler told Bridgend magistrates Strange "found it difficult to cope with falling from grace after being a man of considerable wealth in the 80s."

Strange later said he started shoplifting after the suicide of his best friend, rocker Michael Hutchence, in November 1997.

BEATRICE DALLE

THE stunning French actress starred in the cult 1986 film Betty Blue and adorned the bedroom walls of almost every red-blooded male student.

But sultry Beatrice was given a six-month suspended sentence in 1992 for shoplifting bracelets and rings worth pounds 3,000.

She is reported to have told the court in Paris: "Jewels, I love zem."

0 notes

Text

19/09/24

TW

I've been in an eating disorders unit in London for 17 days now. The first week I really struggled to comply with my meal plan. I ate half the starter plan (around the same as what I'd been having before) and lost a further kg. I found it strangely tolerable, most likely since I was eating the amount I could tolerate at the time, I also had my stash of sweeteners in a hairbrush in my room and went to the garden (twice).

On the fourth day, I was asked by my new consultant psychiatrist to come with her to the clinic room. I sat on the bed waiting. She looked concerned and told me my lithium levels were too high, I wasn't too fussed, I was sure that could be amended. Only she went through symptom after symptom. The only ones I had weren't related to it (dizziness and chest pain to which I'd been experiencing for some time so wasn't worried about anyway).

So asked how I was getting on with my meal plan, to which I said I was struggling. She got to the point quickly and asked if I'd consider the NG. I said I couldn't since it had gone so wrong before and didn't want it to happen again. She nodded and we spoke about my physical health as she was saying I was very unwell and at such a low body weight. I told her I was ok and was probably wasting a bed here. So, she told me that normally she gives longer but she needed to apply for a mental health act assessment as my physical health was too unstable.

I felt sad and frustrated, but in a way I had already had a feeling it may be suggested. I saw my dad that afternoon, where I got a cherry pepsi max and we caught up with each others week before I went to the garden for my second supervised sit down on a bench with another patient. The OT came over and said she'd do an assessment with on Monday, to which I said I probably wouldn't be there for (I was planning to self- discharge the next morning prior to the MHA assessment).

I thought nothing more of it when my psychiatrist came knocking at my door with a member of staff, a mixture of concern and irritation on her face. She said she had just received a call from the OT saying I was going to abscond (I never said that) right before she was about to go home. I explained I was going to pack my things that night and self-discharge the following day as I wasn't using my bed well and didn't feel I needed to be there. Again, she spoke about how physically compromised I was and combined with my lithium levels I was very unwell.

With that, she said she wanted me on 1:1, I reminded her I was a voluntary patient and had the right to refuse that. She agreed, then put me on a section 52 (holding section) as well as stuck me on a 1:1. That was not the response I thought she would have. I had hoped she would have been irritated enough to tell me to just leave and I could have gone. It clearly didn't work out that way!

The following day, just before lunch I was called into the MDT room where two people were waiting (a man and a woman) the man, Seb introduced himself as an AMHP and the lady was the psychiatrist. They were there for a MHA assessment and I inwardly groaned. It didn't last too long, they asked a few questions, before saying how my consultant psych feels I'm at high risk of cardiac arrest among other life threatening complications as a result of "severe" anorexia and very low body weight, especially combined with high lithium levels. Not to mention the fact I wanted to leave.

They went on to say I had a severe lack of insight to the severity of my anorexia and placed me on the dreaded section 3. They didn't even ask me to leave the room so they could discuss, just straight onto a section 3 there and then.

Since then it's been a very testing time. I've managed to mostly avoid the NG, only having it once last week which was enough to cause flashbacks and dissociation. I've gained 1.6kg in 1 week and completely panicked. I can feel the weight gain already and I absolutely hate it.

0 notes

Text

Relocate to the UK - Qualified Psychiatrist

Consultant Level Psychiatrists Needed in the UK.Sanctuary International, a dedicated and award-winning recruitment agency with a Trustpilot score of 4.9/5 with 1000+ reviews, is currently seeking experienced and dedicated Consultant level Psychiatrists to join our teams in Kent, London, Oxford, and Scotland, where we have some positions available.Salary for Consultant level: £93,666 – £126,281…

0 notes

Text

West London NHS Trust: Consultant Forensic Psychiatrist

West London NHS Trust: Consultant Forensic Psychiatrist £99,532 – £131,964: West London NHS Trust: This is an exciting opportunity to work as a Consultant Forensic Psychiatrist in Broadmoor Hospital. Berkshire Information Courtesy By: , HospitalJobs, European, Healthcarejobs | Feeds £99,532 – £131,964: West London NHS Trust: This is an exciting opportunity to work as a Consultant Forensic…

0 notes

Text

ADHD Specialist London - adhd Assessment & Diagnosis

Our mental health clinic specialises in the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD and any other associated conditions with this diagnosis. Our emphasis is to provide the highest services leading to positive results.

Dr Stefan Ivantu - Private Psychiatrist London - ADHD Specialist

10 Harley St, London W1G 9PF, UK

+44 20 7467 8366

Map: https://maps.google.com/?cid=8416843431092268509

0 notes

Link

#adolescenti#Bambini#ChiaraColonnelli#DottoreLondon#francescatagliente.lorenzogragnani#IlCircoloLondon#mentalhealth#stefanodirico

0 notes

Text

🌟 Discover mental well-being with Dr. Pav Kooner, London's expert Private Psychiatrist! Specializing in ADHD and complex cases, Dr. Kooner offers confidential consultations. Your journey to balance starts here. Book now! 🧠💼 #Psychiatry #ADHD #LondonPsychiatrist #MentalHealth

1 note

·

View note

Text

By: Henry Samuel

Published: Mar 23, 2024

French Senators want to ban gender transition treatments for under-18s, after a report described sex reassignment in minors as potentially “one of the greatest ethical scandals in the history of medicine”.

The report, commissioned by the opposition centre-Right Les Republicains (LR) party, documents various practices by health professionals, which it claims are indoctrinated by a “trans-affirmative” ideology under the sway of experienced trans-activist associations.

The report, which cites a “tense scientific and medical debate”, accuses such associations of encouraging gender transition in minors via intense propaganda campaigns on social media.

Jacqueline Eustache-Brinio, an LR senator who led the working group behind the report, concluded that “fashion plays a big role” in the rise of gender reassignment treatments.

If this factor and the risks involved are underestimated, she added, “the sexual transition of young people will be considered as one of the greatest ethical scandals in the history of medicine”.

LR senators now want to table a Bill by the summer that would effectively ban the medical transition of minors in France by halting the prescription or administration of puberty blockers and hormones to people under the age of 18.

Sex reassignment surgery could also be banned for minors.

Reacting to the report, Ypomoni, a French parents’ group, said: “We welcome this return to reason.”

Maud Vasselle, a mother whose daughter underwent gender transition treatment, told Le Figaro: “A child is not old enough to ask to have her body altered.

“My daughter just needed the certificate of a psychiatrist, which she obtained after a one-hour consultation. But doctors don’t explain the consequences of puberty blockers,” she added.

“My daughter didn’t realise that life wasn’t going to be so easy with all these treatments... She was a brilliant little girl but now she’s failing at school. And she is far from having found the solution to her problems.”

Shocking and ideological

Transgender activists and certain health professionals expressed alarm at the report.

Clément Moreau, the clinical psychologist and coordinator of the mental health unit of the association Espace Santé Trans (Trans Health Space), said the report was “shocking” and called the move “ideological”.

“Using blockers if necessary or hormones before coming of age reduces the rate of suicidality, depression and anxiety,” he added.

The French report comes after the NHS banned children from receiving puberty blockers on prescription earlier this month.

France’s health regulation body, the Haute Autorité de Santé, was already examining a similar move.

The LR senators want to accelerate the process following the report.

Citing British, Swedish and American studies, the report said that the number of children identifying themselves as trans has exploded over the past decade.

One hospital in Paris receives around 40 new requests from minors every year, with 16 per cent of those under the age of 12 and the report points out that many suffer from other issues.

A quarter of the children seen at the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital for gender dysphoria have dropped out of school, 42 per cent have been victims of harassment, and 61 per cent have experienced an episode of depression. One in five has attempted suicide.

Their conclusions are in line with those of British experts called in to investigate London’s Tavistock clinic over its use of mass gender reassignment surgery on minors.

David Bell. a British psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, found that a third of the children consulted at the Tavistock suffered from autistic disorders, and many were victims of family violence or had difficulty in accepting or expressing homosexuality, yet they were rushed into gender transition regardless.

#France#medical scandal#medical malpractice#medical corruption#queer theory#gender identity ideology#gender ideology#intersectional feminism#gender affirming healthcare#gender affirming care#gender affirmation#gay conversion therapy#gay conversion#puberty blockers#wrong sex hormones#cross sex hormones#gender lobotomy#gender pseudoscience#pseudoscience#gender homeopathy#religion is a mental illness

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ultimate Guide on Depression Treatment: 5 Proven Strategies by Dr. Ali Kala

Are you or someone you know struggling with depression? You're not alone. Depression affects millions of people worldwide, making it crucial to understand effective Depression Treatment in London options. In this article, we'll explore five top strategies for treating depression that are not only recognized by experts but also backed by Google searches. Let's dive in and find the path to a brighter, healthier life.

Understanding Depression

Depression is more than just feeling sad; it's a complex mental health condition that affects thoughts, emotions, and daily functioning. It's crucial to differentiate between occasional blues and clinical depression, which often requires specialized treatment.

The Importance of Seeking Professional Help

If you're experiencing persistent symptoms of depression, seeking help from a mental health professional is essential. Therapists, psychologists, and psychiatrists can provide personalized guidance and evidence-based interventions to support your journey to recovery.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

CBT is a widely recognized therapy for depression. It focuses on identifying negative thought patterns and replacing them with healthier ones. Through structured sessions, individuals learn coping skills and strategies to manage their emotions effectively.

Medication and its Role in Treatment

Antidepressant medications can be effective in managing depression, especially when combined with therapy. SSRIs and SNRIs are commonly prescribed, but it's essential to consult a medical professional to determine the right approach for you.

Lifestyle Changes and Self-Care

Simple lifestyle changes can have a significant impact on mental well-being. Adequate sleep, a balanced diet, and engaging in activities you enjoy can contribute to overall mood improvement.

Exercise's Impact on Mental Health

Physical activity is linked to the release of endorphins, which are natural mood lifters. Incorporating regular exercise into your routine can help alleviate symptoms of depression and boost self-esteem.

The Power of a Support System

Having a strong support system is invaluable. Surround yourself with friends and family who understand and encourage your journey. Their presence can provide emotional nourishment during tough times.

Exploring Alternative Therapies

In addition to traditional treatments, alternative therapies like art therapy, music therapy, and acupuncture have shown promise in complementing depression treatment in London. However, consult professionals before trying these approaches.

Mindfulness and Meditation Practices

Practices like mindfulness and meditation can enhance emotional regulation and reduce stress. They encourage living in the present moment, fostering a sense of calm and reducing rumination.

Overcoming Barriers to Treatment

Many individuals face barriers such as stigma or lack of access to treatment. It's important to address these challenges and seek help despite them. Online therapy and support groups can be accessible alternatives.

Recognizing Early Warning Signs

Being aware of early signs of depression recurrence empowers individuals to take action promptly. These signs can include changes in sleep patterns, appetite, energy levels, and interest in activities.

Building Resilience and Preventing Relapse

Developing resilience is crucial in maintaining long-term well-being. Learning healthy coping mechanisms and stress management techniques can help prevent relapses.

Depression in Children and Adolescents

Depression can affect people of all ages, including children and adolescents. It's essential for parents, caregivers, and educators to recognize signs in young individuals and provide appropriate support.

Nurturing Emotional Well-Being

Prioritizing emotional well-being is an ongoing journey. Engaging in activities that bring joy, practicing gratitude, and fostering healthy relationships contribute to overall mental health.

Conclusion