#Lombards as the last great wave

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Lombards as the last great wave

Old histories see the Lombards as the last great wave of barbarian hordes swooping down into Italy, but they were far more normal in Roman terms. Relocated in Italy, seizing the high ground, cowing their neighbors into grudging submission (for there was no one from whom to expect rescue), they promptly subsided. Their great leader Alboin, who had won the war against the Gepids and then led his forces into Italy, was overthrown and murdered in 572 at the hand of his wife Rosamund and a henchman, and his successor Clef lasted barely a year. For another ten years, the Lombards in Italy made do without a single leader. You could draw a map to show for every square foot of Italy at that time whether Lombards or Romans claimed suzerainty there, but over considerable stretches of country local lords held sway and the patterns we saw already under the rule of Theoderic’s successors grew stronger. A few landlords and a few soldiers could give a valley a semblance of government, whatever its notional relationship to some ruler elsewhere might be. Many of those landlords, moreover, were newcomers, military figures of sometimes ambiguous provenance, who had settled in Italy on vacant lands— sometimes forcibly vacated, of course—after Justinian’s great debilitating wars. If no one thought of them either as warlords or as barbarians, they were still men to be reckoned with in their petty domains, and were for the most part left undisturbed by more ambitious rulers elsewhere, who had enough to do just to maintain their own pretense of power.

Philo-Roman and Catholic queen

The best—not truest—yarns about them come from a writer more than a century later: Paul the Deacon. Admiring frescoes in the church at Monza, just north of Milan, commissioned by a very philo-Roman and Catholic queen of the Lombards, Theodelinda, Paul created what was for a long time the standard picture of the Lombards: “They exposed their forehead and shaved all the way round to the neck, while their hair, combed down on either side of the head to the level of the mouth, was parted at the centre. Their clothing was roomy, mainly made of linen, like the Anglo-Saxons wear, decorated with broad bands woven in various colours. Their boots were open at the big toe, held in place by interwoven leather thongs. Later on they began to use thigh boots, over which they put woollen greaves when out riding, in Roman fashion.” Theodelinda had been the queen of Authari; when he died in 590, she chose to call Agilulf to the throne as her spouse. While he reigned she undertook to advance the cause of Nicene Christianity, winning Pope Gregory’s friendship and flattery. In the treasure house of the cathedral at Monza there survives today a splendidly detailed small-scale gilded silver sculpture of a mother hen and its chicks, probably a gift from Gregory to her.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Lombards as the last great wave

Old histories see the Lombards as the last great wave of barbarian hordes swooping down into Italy, but they were far more normal in Roman terms. Relocated in Italy, seizing the high ground, cowing their neighbors into grudging submission (for there was no one from whom to expect rescue), they promptly subsided. Their great leader Alboin, who had won the war against the Gepids and then led his forces into Italy, was overthrown and murdered in 572 at the hand of his wife Rosamund and a henchman, and his successor Clef lasted barely a year. For another ten years, the Lombards in Italy made do without a single leader. You could draw a map to show for every square foot of Italy at that time whether Lombards or Romans claimed suzerainty there, but over considerable stretches of country local lords held sway and the patterns we saw already under the rule of Theoderic’s successors grew stronger. A few landlords and a few soldiers could give a valley a semblance of government, whatever its notional relationship to some ruler elsewhere might be. Many of those landlords, moreover, were newcomers, military figures of sometimes ambiguous provenance, who had settled in Italy on vacant lands— sometimes forcibly vacated, of course—after Justinian’s great debilitating wars. If no one thought of them either as warlords or as barbarians, they were still men to be reckoned with in their petty domains, and were for the most part left undisturbed by more ambitious rulers elsewhere, who had enough to do just to maintain their own pretense of power.

Philo-Roman and Catholic queen

The best—not truest—yarns about them come from a writer more than a century later: Paul the Deacon. Admiring frescoes in the church at Monza, just north of Milan, commissioned by a very philo-Roman and Catholic queen of the Lombards, Theodelinda, Paul created what was for a long time the standard picture of the Lombards: “They exposed their forehead and shaved all the way round to the neck, while their hair, combed down on either side of the head to the level of the mouth, was parted at the centre. Their clothing was roomy, mainly made of linen, like the Anglo-Saxons wear, decorated with broad bands woven in various colours. Their boots were open at the big toe, held in place by interwoven leather thongs. Later on they began to use thigh boots, over which they put woollen greaves when out riding, in Roman fashion.” Theodelinda had been the queen of Authari; when he died in 590, she chose to call Agilulf to the throne as her spouse. While he reigned she undertook to advance the cause of Nicene Christianity, winning Pope Gregory’s friendship and flattery. In the treasure house of the cathedral at Monza there survives today a splendidly detailed small-scale gilded silver sculpture of a mother hen and its chicks, probably a gift from Gregory to her.

0 notes

Photo

Lombards as the last great wave

Old histories see the Lombards as the last great wave of barbarian hordes swooping down into Italy, but they were far more normal in Roman terms. Relocated in Italy, seizing the high ground, cowing their neighbors into grudging submission (for there was no one from whom to expect rescue), they promptly subsided. Their great leader Alboin, who had won the war against the Gepids and then led his forces into Italy, was overthrown and murdered in 572 at the hand of his wife Rosamund and a henchman, and his successor Clef lasted barely a year. For another ten years, the Lombards in Italy made do without a single leader. You could draw a map to show for every square foot of Italy at that time whether Lombards or Romans claimed suzerainty there, but over considerable stretches of country local lords held sway and the patterns we saw already under the rule of Theoderic’s successors grew stronger. A few landlords and a few soldiers could give a valley a semblance of government, whatever its notional relationship to some ruler elsewhere might be. Many of those landlords, moreover, were newcomers, military figures of sometimes ambiguous provenance, who had settled in Italy on vacant lands— sometimes forcibly vacated, of course—after Justinian’s great debilitating wars. If no one thought of them either as warlords or as barbarians, they were still men to be reckoned with in their petty domains, and were for the most part left undisturbed by more ambitious rulers elsewhere, who had enough to do just to maintain their own pretense of power.

Philo-Roman and Catholic queen

The best—not truest—yarns about them come from a writer more than a century later: Paul the Deacon. Admiring frescoes in the church at Monza, just north of Milan, commissioned by a very philo-Roman and Catholic queen of the Lombards, Theodelinda, Paul created what was for a long time the standard picture of the Lombards: “They exposed their forehead and shaved all the way round to the neck, while their hair, combed down on either side of the head to the level of the mouth, was parted at the centre. Their clothing was roomy, mainly made of linen, like the Anglo-Saxons wear, decorated with broad bands woven in various colours. Their boots were open at the big toe, held in place by interwoven leather thongs. Later on they began to use thigh boots, over which they put woollen greaves when out riding, in Roman fashion.” Theodelinda had been the queen of Authari; when he died in 590, she chose to call Agilulf to the throne as her spouse. While he reigned she undertook to advance the cause of Nicene Christianity, winning Pope Gregory’s friendship and flattery. In the treasure house of the cathedral at Monza there survives today a splendidly detailed small-scale gilded silver sculpture of a mother hen and its chicks, probably a gift from Gregory to her.

0 notes

Photo

Lombards as the last great wave

Old histories see the Lombards as the last great wave of barbarian hordes swooping down into Italy, but they were far more normal in Roman terms. Relocated in Italy, seizing the high ground, cowing their neighbors into grudging submission (for there was no one from whom to expect rescue), they promptly subsided. Their great leader Alboin, who had won the war against the Gepids and then led his forces into Italy, was overthrown and murdered in 572 at the hand of his wife Rosamund and a henchman, and his successor Clef lasted barely a year. For another ten years, the Lombards in Italy made do without a single leader. You could draw a map to show for every square foot of Italy at that time whether Lombards or Romans claimed suzerainty there, but over considerable stretches of country local lords held sway and the patterns we saw already under the rule of Theoderic’s successors grew stronger. A few landlords and a few soldiers could give a valley a semblance of government, whatever its notional relationship to some ruler elsewhere might be. Many of those landlords, moreover, were newcomers, military figures of sometimes ambiguous provenance, who had settled in Italy on vacant lands— sometimes forcibly vacated, of course—after Justinian’s great debilitating wars. If no one thought of them either as warlords or as barbarians, they were still men to be reckoned with in their petty domains, and were for the most part left undisturbed by more ambitious rulers elsewhere, who had enough to do just to maintain their own pretense of power.

Philo-Roman and Catholic queen

The best—not truest—yarns about them come from a writer more than a century later: Paul the Deacon. Admiring frescoes in the church at Monza, just north of Milan, commissioned by a very philo-Roman and Catholic queen of the Lombards, Theodelinda, Paul created what was for a long time the standard picture of the Lombards: “They exposed their forehead and shaved all the way round to the neck, while their hair, combed down on either side of the head to the level of the mouth, was parted at the centre. Their clothing was roomy, mainly made of linen, like the Anglo-Saxons wear, decorated with broad bands woven in various colours. Their boots were open at the big toe, held in place by interwoven leather thongs. Later on they began to use thigh boots, over which they put woollen greaves when out riding, in Roman fashion.” Theodelinda had been the queen of Authari; when he died in 590, she chose to call Agilulf to the throne as her spouse. While he reigned she undertook to advance the cause of Nicene Christianity, winning Pope Gregory’s friendship and flattery. In the treasure house of the cathedral at Monza there survives today a splendidly detailed small-scale gilded silver sculpture of a mother hen and its chicks, probably a gift from Gregory to her.

0 notes

Photo

Lombards as the last great wave

Old histories see the Lombards as the last great wave of barbarian hordes swooping down into Italy, but they were far more normal in Roman terms. Relocated in Italy, seizing the high ground, cowing their neighbors into grudging submission (for there was no one from whom to expect rescue), they promptly subsided. Their great leader Alboin, who had won the war against the Gepids and then led his forces into Italy, was overthrown and murdered in 572 at the hand of his wife Rosamund and a henchman, and his successor Clef lasted barely a year. For another ten years, the Lombards in Italy made do without a single leader. You could draw a map to show for every square foot of Italy at that time whether Lombards or Romans claimed suzerainty there, but over considerable stretches of country local lords held sway and the patterns we saw already under the rule of Theoderic’s successors grew stronger. A few landlords and a few soldiers could give a valley a semblance of government, whatever its notional relationship to some ruler elsewhere might be. Many of those landlords, moreover, were newcomers, military figures of sometimes ambiguous provenance, who had settled in Italy on vacant lands— sometimes forcibly vacated, of course—after Justinian’s great debilitating wars. If no one thought of them either as warlords or as barbarians, they were still men to be reckoned with in their petty domains, and were for the most part left undisturbed by more ambitious rulers elsewhere, who had enough to do just to maintain their own pretense of power.

Philo-Roman and Catholic queen

The best—not truest—yarns about them come from a writer more than a century later: Paul the Deacon. Admiring frescoes in the church at Monza, just north of Milan, commissioned by a very philo-Roman and Catholic queen of the Lombards, Theodelinda, Paul created what was for a long time the standard picture of the Lombards: “They exposed their forehead and shaved all the way round to the neck, while their hair, combed down on either side of the head to the level of the mouth, was parted at the centre. Their clothing was roomy, mainly made of linen, like the Anglo-Saxons wear, decorated with broad bands woven in various colours. Their boots were open at the big toe, held in place by interwoven leather thongs. Later on they began to use thigh boots, over which they put woollen greaves when out riding, in Roman fashion.” Theodelinda had been the queen of Authari; when he died in 590, she chose to call Agilulf to the throne as her spouse. While he reigned she undertook to advance the cause of Nicene Christianity, winning Pope Gregory’s friendship and flattery. In the treasure house of the cathedral at Monza there survives today a splendidly detailed small-scale gilded silver sculpture of a mother hen and its chicks, probably a gift from Gregory to her.

0 notes

Photo

Lombards as the last great wave

Old histories see the Lombards as the last great wave of barbarian hordes swooping down into Italy, but they were far more normal in Roman terms. Relocated in Italy, seizing the high ground, cowing their neighbors into grudging submission (for there was no one from whom to expect rescue), they promptly subsided. Their great leader Alboin, who had won the war against the Gepids and then led his forces into Italy, was overthrown and murdered in 572 at the hand of his wife Rosamund and a henchman, and his successor Clef lasted barely a year. For another ten years, the Lombards in Italy made do without a single leader. You could draw a map to show for every square foot of Italy at that time whether Lombards or Romans claimed suzerainty there, but over considerable stretches of country local lords held sway and the patterns we saw already under the rule of Theoderic’s successors grew stronger. A few landlords and a few soldiers could give a valley a semblance of government, whatever its notional relationship to some ruler elsewhere might be. Many of those landlords, moreover, were newcomers, military figures of sometimes ambiguous provenance, who had settled in Italy on vacant lands— sometimes forcibly vacated, of course—after Justinian’s great debilitating wars. If no one thought of them either as warlords or as barbarians, they were still men to be reckoned with in their petty domains, and were for the most part left undisturbed by more ambitious rulers elsewhere, who had enough to do just to maintain their own pretense of power.

Philo-Roman and Catholic queen

The best—not truest—yarns about them come from a writer more than a century later: Paul the Deacon. Admiring frescoes in the church at Monza, just north of Milan, commissioned by a very philo-Roman and Catholic queen of the Lombards, Theodelinda, Paul created what was for a long time the standard picture of the Lombards: “They exposed their forehead and shaved all the way round to the neck, while their hair, combed down on either side of the head to the level of the mouth, was parted at the centre. Their clothing was roomy, mainly made of linen, like the Anglo-Saxons wear, decorated with broad bands woven in various colours. Their boots were open at the big toe, held in place by interwoven leather thongs. Later on they began to use thigh boots, over which they put woollen greaves when out riding, in Roman fashion.” Theodelinda had been the queen of Authari; when he died in 590, she chose to call Agilulf to the throne as her spouse. While he reigned she undertook to advance the cause of Nicene Christianity, winning Pope Gregory’s friendship and flattery. In the treasure house of the cathedral at Monza there survives today a splendidly detailed small-scale gilded silver sculpture of a mother hen and its chicks, probably a gift from Gregory to her.

0 notes

Photo

Lombards as the last great wave

Old histories see the Lombards as the last great wave of barbarian hordes swooping down into Italy, but they were far more normal in Roman terms. Relocated in Italy, seizing the high ground, cowing their neighbors into grudging submission (for there was no one from whom to expect rescue), they promptly subsided. Their great leader Alboin, who had won the war against the Gepids and then led his forces into Italy, was overthrown and murdered in 572 at the hand of his wife Rosamund and a henchman, and his successor Clef lasted barely a year. For another ten years, the Lombards in Italy made do without a single leader. You could draw a map to show for every square foot of Italy at that time whether Lombards or Romans claimed suzerainty there, but over considerable stretches of country local lords held sway and the patterns we saw already under the rule of Theoderic’s successors grew stronger. A few landlords and a few soldiers could give a valley a semblance of government, whatever its notional relationship to some ruler elsewhere might be. Many of those landlords, moreover, were newcomers, military figures of sometimes ambiguous provenance, who had settled in Italy on vacant lands— sometimes forcibly vacated, of course—after Justinian’s great debilitating wars. If no one thought of them either as warlords or as barbarians, they were still men to be reckoned with in their petty domains, and were for the most part left undisturbed by more ambitious rulers elsewhere, who had enough to do just to maintain their own pretense of power.

Philo-Roman and Catholic queen

The best—not truest—yarns about them come from a writer more than a century later: Paul the Deacon. Admiring frescoes in the church at Monza, just north of Milan, commissioned by a very philo-Roman and Catholic queen of the Lombards, Theodelinda, Paul created what was for a long time the standard picture of the Lombards: “They exposed their forehead and shaved all the way round to the neck, while their hair, combed down on either side of the head to the level of the mouth, was parted at the centre. Their clothing was roomy, mainly made of linen, like the Anglo-Saxons wear, decorated with broad bands woven in various colours. Their boots were open at the big toe, held in place by interwoven leather thongs. Later on they began to use thigh boots, over which they put woollen greaves when out riding, in Roman fashion.” Theodelinda had been the queen of Authari; when he died in 590, she chose to call Agilulf to the throne as her spouse. While he reigned she undertook to advance the cause of Nicene Christianity, winning Pope Gregory’s friendship and flattery. In the treasure house of the cathedral at Monza there survives today a splendidly detailed small-scale gilded silver sculpture of a mother hen and its chicks, probably a gift from Gregory to her.

0 notes

Photo

Lombards as the last great wave

Old histories see the Lombards as the last great wave of barbarian hordes swooping down into Italy, but they were far more normal in Roman terms. Relocated in Italy, seizing the high ground, cowing their neighbors into grudging submission (for there was no one from whom to expect rescue), they promptly subsided. Their great leader Alboin, who had won the war against the Gepids and then led his forces into Italy, was overthrown and murdered in 572 at the hand of his wife Rosamund and a henchman, and his successor Clef lasted barely a year. For another ten years, the Lombards in Italy made do without a single leader. You could draw a map to show for every square foot of Italy at that time whether Lombards or Romans claimed suzerainty there, but over considerable stretches of country local lords held sway and the patterns we saw already under the rule of Theoderic’s successors grew stronger. A few landlords and a few soldiers could give a valley a semblance of government, whatever its notional relationship to some ruler elsewhere might be. Many of those landlords, moreover, were newcomers, military figures of sometimes ambiguous provenance, who had settled in Italy on vacant lands— sometimes forcibly vacated, of course—after Justinian’s great debilitating wars. If no one thought of them either as warlords or as barbarians, they were still men to be reckoned with in their petty domains, and were for the most part left undisturbed by more ambitious rulers elsewhere, who had enough to do just to maintain their own pretense of power.

Philo-Roman and Catholic queen

The best—not truest—yarns about them come from a writer more than a century later: Paul the Deacon. Admiring frescoes in the church at Monza, just north of Milan, commissioned by a very philo-Roman and Catholic queen of the Lombards, Theodelinda, Paul created what was for a long time the standard picture of the Lombards: “They exposed their forehead and shaved all the way round to the neck, while their hair, combed down on either side of the head to the level of the mouth, was parted at the centre. Their clothing was roomy, mainly made of linen, like the Anglo-Saxons wear, decorated with broad bands woven in various colours. Their boots were open at the big toe, held in place by interwoven leather thongs. Later on they began to use thigh boots, over which they put woollen greaves when out riding, in Roman fashion.” Theodelinda had been the queen of Authari; when he died in 590, she chose to call Agilulf to the throne as her spouse. While he reigned she undertook to advance the cause of Nicene Christianity, winning Pope Gregory’s friendship and flattery. In the treasure house of the cathedral at Monza there survives today a splendidly detailed small-scale gilded silver sculpture of a mother hen and its chicks, probably a gift from Gregory to her.

0 notes

Photo

Lombards as the last great wave

Old histories see the Lombards as the last great wave of barbarian hordes swooping down into Italy, but they were far more normal in Roman terms. Relocated in Italy, seizing the high ground, cowing their neighbors into grudging submission (for there was no one from whom to expect rescue), they promptly subsided. Their great leader Alboin, who had won the war against the Gepids and then led his forces into Italy, was overthrown and murdered in 572 at the hand of his wife Rosamund and a henchman, and his successor Clef lasted barely a year. For another ten years, the Lombards in Italy made do without a single leader. You could draw a map to show for every square foot of Italy at that time whether Lombards or Romans claimed suzerainty there, but over considerable stretches of country local lords held sway and the patterns we saw already under the rule of Theoderic’s successors grew stronger. A few landlords and a few soldiers could give a valley a semblance of government, whatever its notional relationship to some ruler elsewhere might be. Many of those landlords, moreover, were newcomers, military figures of sometimes ambiguous provenance, who had settled in Italy on vacant lands— sometimes forcibly vacated, of course—after Justinian’s great debilitating wars. If no one thought of them either as warlords or as barbarians, they were still men to be reckoned with in their petty domains, and were for the most part left undisturbed by more ambitious rulers elsewhere, who had enough to do just to maintain their own pretense of power.

Philo-Roman and Catholic queen

The best—not truest—yarns about them come from a writer more than a century later: Paul the Deacon. Admiring frescoes in the church at Monza, just north of Milan, commissioned by a very philo-Roman and Catholic queen of the Lombards, Theodelinda, Paul created what was for a long time the standard picture of the Lombards: “They exposed their forehead and shaved all the way round to the neck, while their hair, combed down on either side of the head to the level of the mouth, was parted at the centre. Their clothing was roomy, mainly made of linen, like the Anglo-Saxons wear, decorated with broad bands woven in various colours. Their boots were open at the big toe, held in place by interwoven leather thongs. Later on they began to use thigh boots, over which they put woollen greaves when out riding, in Roman fashion.” Theodelinda had been the queen of Authari; when he died in 590, she chose to call Agilulf to the throne as her spouse. While he reigned she undertook to advance the cause of Nicene Christianity, winning Pope Gregory’s friendship and flattery. In the treasure house of the cathedral at Monza there survives today a splendidly detailed small-scale gilded silver sculpture of a mother hen and its chicks, probably a gift from Gregory to her.

0 notes

Photo

Lombards as the last great wave

Old histories see the Lombards as the last great wave of barbarian hordes swooping down into Italy, but they were far more normal in Roman terms. Relocated in Italy, seizing the high ground, cowing their neighbors into grudging submission (for there was no one from whom to expect rescue), they promptly subsided. Their great leader Alboin, who had won the war against the Gepids and then led his forces into Italy, was overthrown and murdered in 572 at the hand of his wife Rosamund and a henchman, and his successor Clef lasted barely a year. For another ten years, the Lombards in Italy made do without a single leader. You could draw a map to show for every square foot of Italy at that time whether Lombards or Romans claimed suzerainty there, but over considerable stretches of country local lords held sway and the patterns we saw already under the rule of Theoderic’s successors grew stronger. A few landlords and a few soldiers could give a valley a semblance of government, whatever its notional relationship to some ruler elsewhere might be. Many of those landlords, moreover, were newcomers, military figures of sometimes ambiguous provenance, who had settled in Italy on vacant lands— sometimes forcibly vacated, of course—after Justinian’s great debilitating wars. If no one thought of them either as warlords or as barbarians, they were still men to be reckoned with in their petty domains, and were for the most part left undisturbed by more ambitious rulers elsewhere, who had enough to do just to maintain their own pretense of power.

Philo-Roman and Catholic queen

The best—not truest—yarns about them come from a writer more than a century later: Paul the Deacon. Admiring frescoes in the church at Monza, just north of Milan, commissioned by a very philo-Roman and Catholic queen of the Lombards, Theodelinda, Paul created what was for a long time the standard picture of the Lombards: “They exposed their forehead and shaved all the way round to the neck, while their hair, combed down on either side of the head to the level of the mouth, was parted at the centre. Their clothing was roomy, mainly made of linen, like the Anglo-Saxons wear, decorated with broad bands woven in various colours. Their boots were open at the big toe, held in place by interwoven leather thongs. Later on they began to use thigh boots, over which they put woollen greaves when out riding, in Roman fashion.” Theodelinda had been the queen of Authari; when he died in 590, she chose to call Agilulf to the throne as her spouse. While he reigned she undertook to advance the cause of Nicene Christianity, winning Pope Gregory’s friendship and flattery. In the treasure house of the cathedral at Monza there survives today a splendidly detailed small-scale gilded silver sculpture of a mother hen and its chicks, probably a gift from Gregory to her.

0 notes

Photo

Lombards as the last great wave

Old histories see the Lombards as the last great wave of barbarian hordes swooping down into Italy, but they were far more normal in Roman terms. Relocated in Italy, seizing the high ground, cowing their neighbors into grudging submission (for there was no one from whom to expect rescue), they promptly subsided. Their great leader Alboin, who had won the war against the Gepids and then led his forces into Italy, was overthrown and murdered in 572 at the hand of his wife Rosamund and a henchman, and his successor Clef lasted barely a year. For another ten years, the Lombards in Italy made do without a single leader. You could draw a map to show for every square foot of Italy at that time whether Lombards or Romans claimed suzerainty there, but over considerable stretches of country local lords held sway and the patterns we saw already under the rule of Theoderic’s successors grew stronger. A few landlords and a few soldiers could give a valley a semblance of government, whatever its notional relationship to some ruler elsewhere might be. Many of those landlords, moreover, were newcomers, military figures of sometimes ambiguous provenance, who had settled in Italy on vacant lands— sometimes forcibly vacated, of course—after Justinian’s great debilitating wars. If no one thought of them either as warlords or as barbarians, they were still men to be reckoned with in their petty domains, and were for the most part left undisturbed by more ambitious rulers elsewhere, who had enough to do just to maintain their own pretense of power.

Philo-Roman and Catholic queen

The best—not truest—yarns about them come from a writer more than a century later: Paul the Deacon. Admiring frescoes in the church at Monza, just north of Milan, commissioned by a very philo-Roman and Catholic queen of the Lombards, Theodelinda, Paul created what was for a long time the standard picture of the Lombards: “They exposed their forehead and shaved all the way round to the neck, while their hair, combed down on either side of the head to the level of the mouth, was parted at the centre. Their clothing was roomy, mainly made of linen, like the Anglo-Saxons wear, decorated with broad bands woven in various colours. Their boots were open at the big toe, held in place by interwoven leather thongs. Later on they began to use thigh boots, over which they put woollen greaves when out riding, in Roman fashion.” Theodelinda had been the queen of Authari; when he died in 590, she chose to call Agilulf to the throne as her spouse. While he reigned she undertook to advance the cause of Nicene Christianity, winning Pope Gregory’s friendship and flattery. In the treasure house of the cathedral at Monza there survives today a splendidly detailed small-scale gilded silver sculpture of a mother hen and its chicks, probably a gift from Gregory to her.

0 notes

Text

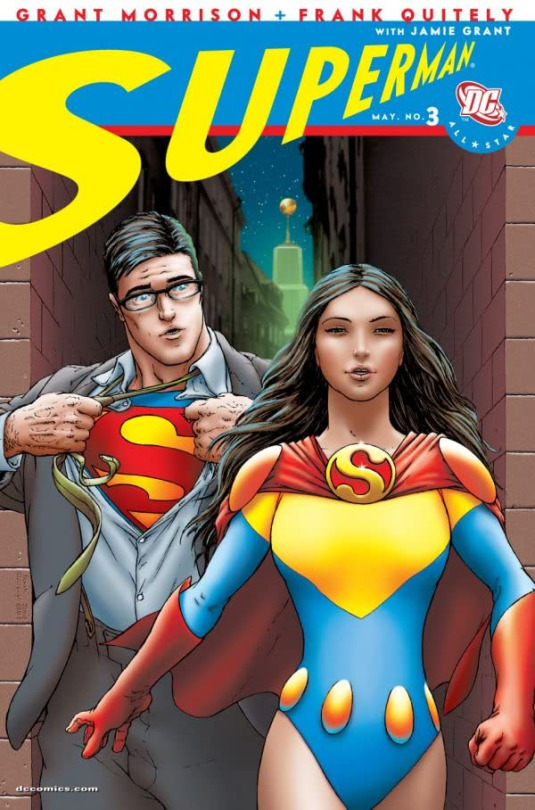

All-Star Superman #3

This is gonna be a tough one.

Not the toughest, mind you - that’s probably going to be #7. But after two issues of establishing the tone, aesthetics, and thematic concerns of the series, this is one of the pair of issues in All-Star that for the most part functions as a ‘normal’ Superman adventure story, though in this case one following up on the themes established by the previous issue, while #7 will set up the one coming after it. It’s also likely the most commonly critiqued issue of the series in retrospect its use of Lois Lane as an essentially passive figure to be fought over, and while her characterization here lends some interesting dimension to that choice, it’s hard to disagree it’s the series’ most unfortunate framing and substantial missed opportunity. None of that however can overrule that on examination, there’s still considerably more going on in here than the traditional tale of Superman beating down monsters and showing up bullies, the harsh slap to the face of reality for Clark after his actions last issue and his redemption in the form of showing what makes him different from his predecessors as the strongman-savior template.

So I haven’t talked the lettering much in this series - it is, they say, the invisible art - but Phil Balsman absolutely kills it here with KRULL WILL EAT YOU!, and the decision on the next page to render the ZEE ZEE ZEE ZEE of Jimmy Olsen’s signal watch in the font of the title pages is absolutely inspired, nevermind what he does with the Ultrasphinx later on. The bombast of the bastard lizard prince of the underworld and his cronies wreaking havoc aside though, what this page succinctly does is set up the entire conflict of the issue. It’s not just a monster, it’s a monster out of the past mimicking the cover of Action Comics #1, and apparently by way of terraforming Metropolis via steam clouds, trying to take control of Superman’s ‘world’. From Krull to Steve Lombard (“You tell me what a spaceman flying around in his underwear can give her that a good old hunk of prime American manhood can’t?”) to Samson and Atlas to the Ultrasphinx, this is a story of Superman up against dinosaurs in his image.

Ironically, however, it’s this Superman vs. Bros comic that has perhaps the most Bro sensibilities in the series. Per Morrison on the subject, “For that particular story, I wanted to see Superman doing tough guy shit again, like he did in the early days and then again in the 70s, when he was written as a supremely cocky macho bastard for a while. I thought a little bit of that would be an antidote to the slightly soppy, Super–Christ portrayal that was starting to gain ground. Hence Samson’s broken arm, twisted in two directions beyond all repair. And Atlas in the hospital. And then Superman’s got his hot girlfriend dressed like a girl from Krypton and they’re making out on the moon.” That’s not unto itself a problem; it’s a precursor to Morrison’s t-shirt and jeans reinvention in that sense (which leapt back from the 70s to the 30s for inspiration), and when Superman himself finally gets his own back here it’s more than deserved. But it becomes a problem when Lois at theoretically her literal most empowered does little with her new powers and is framed narratively as a prize to be won in this ‘game’ of godlings, with Superman literally muttering “What do I have to do to make you keep your hands off my girl?” Morrison seems to be somewhat aware of the problems given Lois’s reasons for playing along (which are actually rather significant to the point of the issue) and her amused distaste at the suggestion of being ‘won’, and the issue is ultimately something of an argument against the macho storytelling tropes that drive that thinking. But it’s a far cry from the nuanced look at her and Superman’s relationship last issue offered, and there’s no virtue in overlooking it. As will be demonstrated again later on in the series in less structurally-embedded but more pointed ways, this was written almost 15 years ago, and mistakes were made.

Now we get to the book’s superheroed-up takes on Samson and Atlas, who are such delightful assholes. Occupying the Mxyzptlk/Prankster/Bizarro-in-his-friendlier-moods role of being the enemies to make Superman go ‘oh god, this guy’ as much as direct counterparts to him, they’re basically fratboys tooling around history and getting into trouble together, and Superman’s clearly had to clean up their messes before. They’re the champions of myth who operate by a morality that in no way precluded thievery, deception, and murder in pursuit of their grand ‘heroic’ conquests, the alpha male swaggering dipshit dudebro operating on Superman’s scale. And as much as they’re a pair of craven dumbasses who literally compare cock-sizes in here who Lois has no real interest in, their appearance is also the first and one of the only times in the series Superman puffs his chest out and does some traditional iconic posing, and he has good reason to be threatened - they’re trying to ply her with gifts and tales of miraculous feats basically exactly the same way he did last issue. He may have started to come clean with her, but he’s still playing his old Silver Age nervous bachelor games, and now that she’s got powers and costume to match his she’s showing him exactly where that bullshit is going to get him, teaching him a lesson just like he tried to teach her so many once upon a time.

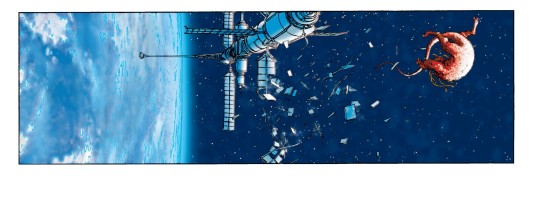

As we’re around the midpoint of the issue, let’s talk the art. Quitely and Grant aren’t as showy with the tricks and effects as the first two issues; the one real noticeable structural thing is a consistent rhythm of zooming in-and-out on our four leads throughout the issue to keep a sense of momentum to a story mostly driven by conversation, culminating in the hyper zoom-ins of the Ultrasphnix sequence. But GOD there are so many perfect little details in here. The bow coming undone on Lois’s present, the glow of the super-serum (it feels so right that it literally glows, the ultimate alchemical potion), Lombard’s bouquet for Lois’s birthday party while Jimmy is bringing a conch of some sort as a presumed gift to whoever they’ll be meeting at Poseidonis, Jimmy’s happy-meal looking signal watch WHICH HAS A WRISTBAND SHAPED LIKE AN S, more beautiful Metropolis architecture and a good look at how the Daily Planet globe actually works, poor dopey-lookin’ Krull bursting through the satellite twirling around like a cat in a half-second of freefall, the Chronomobile, the far-off monumental stone towers of the Subterranosauri, the glow of the lava fading out as Samson reveals Superman’s fate, the bioelectric crackle around Atom-Hotep, mermaids waving up at Superman and Lois, and of course the pinup. It’s such a damn pretty book.

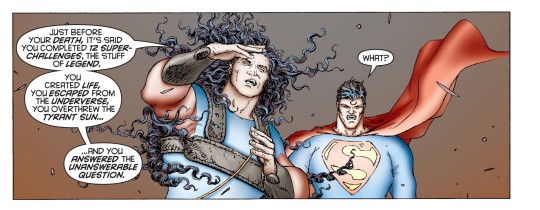

Just before the arrival of the Ultrasphnix, we have the mythic architecture of the series explained to us, naturally by the figure out of myth:

As noted by Morrison, the exact nature of the 12 challenges are never explained within the story because it’s only in retrospect that history will declare those specific feats as being of note in light of them being Superman’s last accomplishments before his ‘death’; Superman himself isn’t sure how many he’s done later on. It’s an apt if seemingly out-of-left-field bit of commentary on the way epics of the kind this story itself aspires towards are reinterpreted over time, but hindsight being 20/20? That this is a story of a massively iconic, archetypal take on Superman being brought out of the public eye to his physical and emotional lowest at every turn (hence the ACTUAL structure of the series being a solar arc across the sky, from day to a nighttime journey through the underworld and back again), that is now generally thought of being a fun fluffy story of how great and perfect Superman is, entirely bears it out. The 12 Labors of Superman are what Clark’s roughest year looks like to the awestruck onlookers, both in and as it turns out in large part out of text.

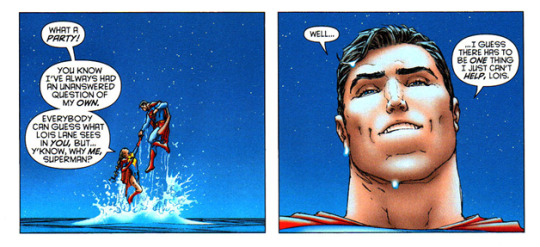

After Samson and Atlas seemingly show nobler colors by offering Superman aid in a genuinely stirring moment before Superman accurately dismisses it as the empty machismo posturing it is, Ultrasphinx - yet another super-champion of the past, this one an amoral god rather than a ‘hero’ on a quest - poses the unanswerable question of what happens when the unstoppable force meets the immovable object with Lois both alive and dead until he does (one of those unions of opposites Morrison loves), basically creating a high-stakes literalization of their relationship. Superman and Lois Lane had been playing will-they-or-won’t-they for almost 70 years at the time this was published (culturally at least), her trying to pry into his secrets while he screwed around with her in turn, running in circles until we finally reach the acidic psychodrama of Superman’s Forbidden Room and something has to break one way or another. And Superman answers that it’s time to surrender. Has he inspired the car ad we see at the end of the issue, or vice-versa? Either way, it’s illustrating by example what the deal is with the super-labors.

Superman, learning his lesson as he has and showing his greater heroism stems from his nobility, intellect, and willingness to transcend his worst instincts, still takes a minute to teach Samson and Atlas a well-deserved lesson (paired with that absolutely perfect shot of the rock cracking on Lois’s head), before taking us to my absolute favorite statement on why Superman loves Lois Lane which also connects back to the idea of surrender, and the iconic moon shot. And as Superman holds her as she falls asleep, his Clark voice in all its vulnerable humanity manifests itself as he tries to propose; the tough guys of the past wanted Lois for a day when she was finally operating on ‘their level’, Superman ‘lowers’ himself to his most human alongside her reassumed mortality as he tries to tell her he wants her for what lifetime he has left. We’re only halfway there at most, he still hasn’t admitted his condition and she still can’t accept that he’s Clark, but this is Superman taking his first step along his quiet character arc.

Additional notes

* Interestingly, the original solicitation for this issue declared “Meanwhile, Lex Luthor's plans simmer as the criminal mastermind exerts his charisma and intellect over the hardcore inmates who share his maximum-security prison.” One of many bits that changed in the process of actually putting the book together.

* Perhaps this story of very manly men out of time doing manly stuff and getting their asses kicked for it across generations is represented in part by Krull being the son of a king whose battle cry is KRULL WILL EAT YOUR CHILL-DRUNN! That might be reading a *bit* much into it though. That Morrison describes Krull in backmatter however as “the living embodiment of the savage, swaggering ‘R Complex’ or reptile brain” definitely plays into the ideas of the issue as I understood them.

* Jimmy’s declaration of “Ms. Grant, Mr. Lombard, I’m taking immediate steps” is a perfect little moment for him - he’s calm and on top of things, but there’s also that little touch of naive ego in thinking that it’s thanks to him that Superman’s going to notice the dinosaur invasion of Metropolis.

* In backmatter and interviews Morrison had substantially further fleshed-out backstories for several of the new characters here. Samson is indeed the original champion, plucked from his era by a pair of foolish time-travelers searching for a savior; instead, enamored and corrupted by future culture he stole their malfunctioning Chronomobile and went on adventures to slake his lust, for fortune, flesh, and adventure alike. Atlas meanwhile is the boisterous yet quietly burdened young prince of the New Mythos, a society of super-godlings torn between New Elysium and Hadia, Morrison’s vision of a Jack Kirby Olympian saga for DC following in the wake of Thor’s Norse myths rather than the full-blown invention of the New Gods. And the Ultrasphinx “is the super-champion of a lost Egyptian Atomic Age in the 80th century BC. When he crashed to Earth his otherworldly science founded the advanced, ancient dynasty of Atem-Hotep [sic], a civilization eventually destroyed by the nuclear war that left Northern Africa a desert”. A. Morrison backmatter rules and you should read it whenever you get the chance, and B. This notion of proto-civilizations mirroring the eventual legends of a mere handful of millennia past is one he followed much further in Seven Soldiers of Victory with Shining Knight and its antediluvian Camelot.

* The main inspiration for this particular story was the frequent use of ancient strongmen as rivals to the Man of Steel in the Silver Age, which Morrison noted preferring to the use of analogue characters like Majestic for their broad cultural standing, culminating in this:

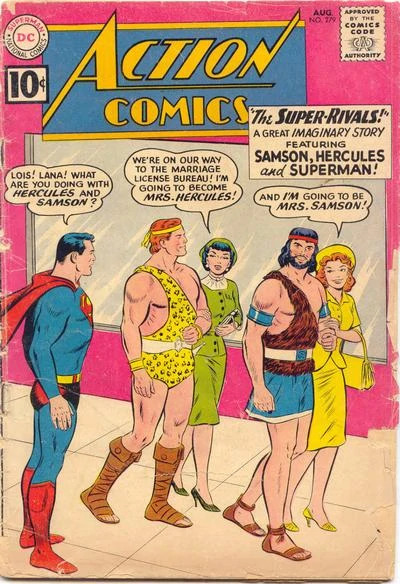

...though with Atlas swapped in, as Marvel already had the definitive take on Hercules in superhero comics (and, one imagines, since putting Hercules in the comic where Superman gets 12 labors would have had to be addressed), though he’d tackle him later on in the...controversial Wonder Woman: Earth One. Morrison’s analysis of this cover in Supergods basically lays out the thesis of this issue quite cleanly: “This was what happened when you couldn’t make decisions or offer any lasting commitment. Samson pounced on your best girl. And for Superman, it was a horrific challenge to his modernity. Was he really no better than these archaic toughs? Or could he prove himself stronger, faster than any previous man-god?” Fun fact: I myself hate this comic because it’s an entirely standard issue that fully returns to status quo by the end, sullying the good name and promise of Imaginary Stories for nothing more than fooling readers into thinking this was one of the issues were anything could really happen. Shameful false advertisement.

* Worth noting this is a rare instance where the glowing-red angry heat vision eyes work for me. Those two were real dicks and had it coming, and for that matter Superman looking for all the world a wrathful god promising banishment to a very different sort of underworld more than underscores his relative position next to the suitably abashed adventurers.

* It’s an interesting choice to use Poseidonis here, the capital city of Aquaman - it’s a sensible place for Superman to travel (though the real implications regarding the Justice League in this world won’t be for awhile yet), but it’s Tritonis that’s the undersea home to Superman’s onetime love, the mermaid Lori Lemaris. Perhaps Morrison just didn’t want a subset of readers in the know and pining after all these decades for Clark to find succor in the arms of his fishy love to dwell on that particular what-could-have-been; either way, Atlantis in general as what sprung up from a devastated ancient civilization is a perfectly logical inclusion for this issue in general.

* Lois’s description of her super-senses is not only lovely, but sets up the victory of #12 right in the first act. Additionally Lois keeping a cactus is such a perfect little bit for her character - it’ll prick ya, but she’s working to keep the thing alive.

* The journeys to the moon and ‘underworld’ for this issue, but in playful and romantic contexts, marks this issue as the (depending on whether you read it as a 4 or 6 issue arc) final installment before All-Star Superman begins its structural descent into the night.

* A very happy birthday to Justin Martin (and a day-before-birthday to myself) with this, annotations of the issue of All-Star Superman about a birthday. Birthdays themselves being a signpost of time and evolution, a forward march, making it a potent occasion to highlight in this series in general and this installment in particular.

#All Star Superman#Superman#Lois Lane#Grant Morrison#Frank Quitely#Jamie Grant#Phil Balsman#Bronze Age#Sexism#Art#Opinion#Analysis

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

Time travel and mutual pining - Christine and Sorelli?

(No cut because I’m on mobile, and this is less mutual pining than it is a hell of a lot of things, and I fully intend to develop it into something more, but this is what it is as it stands tonight, and thank you.)

(Warning that this is, in fact, a long post.)

The first time it happens she is six. Mama and Papa both out of the house and she hears the rattle and thinks it’s the Tans but even she knows the Tans come from outside even though she hasn’t seen them, even though they haven’t come for her Papa.

(They came for Eoin’s papa, but her Papa said that Eoin’s Papa is a toe-rag, and there were other things too but her mama told her that if she repeated them there would be no plum for dessert and there weren’t many plums anyway but she wanted one.)

Maybe a bird has gotten down the chimney. If a bird has gotten down the chimney then it might be trapped and she’ll have to save it and let it out or Mama will get cross, and Mama has been sad she doesn’t want to make her cross.

Nodding to herself, resolved that she is going to rescue this little bird, she puts aside the doll she’s been playing with, and fixes her dress, and wanders towards the source of the noise.

Really it’s as simple as opening a door into the next room, but she pretends to herself that it’s a great adventure, that she’s the Countess and her doll is one of the volunteers and it’s the GPO and they’re hunting down the British soldiers because these are the stories she’s heard and Kitty’s Mama tells them and makes them so exciting it’s like the soldiers are right outside.

And there is no little bird and there are no soldiers but there is a little girl with golden curls and she thinks she should be frightened or maybe she should fight the little girl is only the same size as her and anyway she’s naked.

Is she one of the fairies her nana warned her about?

Fairies aren’t supposed to be little girls. They’re supposed to be something but not little girls.

She might be cold.

“Do you want a dress?”

The girl frowns at her. “Sorelli?”

No one calls her Sorelli. Her papa calls her Ellie May and her nana calls her Eleanor and her mama calls her Ellie but no one calls her Sorelli but it feels like it might be her name.

She decides she likes it.

“Yeah and who are you?”

The girl’s eyes shine bright blue. “Christine.”

*

After the sixth time she stops counting Christine’s visits. She tried telling Mama about them about Mama gave her that smile that means she’s thinking of other things and said “that’s nice, dear.” She might have told Nana but Nana would have told her Christine is a fairy and to stay away from her but Christine isn’t a fairy because Christine never tried to give her anything and never tried to take her away anywhere. She might have told Papa but Papa has been tired a lot, so she decides Christine will be her secret.

She gives Christine old dresses to wear but it doesn’t matter because when Christine disappears (and she does disappear because Ellie has seen it and the first time it frightened her but the secret time she knew what to expect) the dresses stay behind and she folds them up neat.

By the sixth time, shortly after her seventh birthday, Christine’s visits become something else she expects, though she never knows when she will arrive. Christine sings songs she has never heard before, and tells her about her Papa who plays a violin and about crossing the ocean in an aeroplane.

Ellie has never seen an aeroplane, but Eoin says the British soldiers have them for dropping bombs on Germans.

Christine said nothing about bombs though.

Maybe they don’t have bombs or guns, in the future where Christine comes from.

(The idea of traveling through time is one she accepts easier than fairies, because Christine is the proof of it and if Christine says it it must be true.)

*

She is ten the day her parents go to Dublin on the train. Christine keeps her company and they go for a walk by the river and sing, but Christine is gone by the time her parents come home again, and her father is crying when he hugs her. She has never seen him cry before and it makes her want to cry.

She does cry when her mother hugs her and tells her the doctor in Dublin says her father will have to go away for a while.

She’s not stupid and she’s not a little girl. She knows it means he has tuberculosis, that that’s why he coughs all night and why he’s so pale and tired all the time, but she doesn’t want him to go away. Kitty’s father went to Newcastle and he never came back and Martha’s mother went to Peamount and she did come back but she died a few months later and so did Martha’s little sister and Eoin has it in his bones and it bent his back and that’s why he’s not allowed out anymore except to go to school.

She doesn’t want her father to die.

(By the time Christine comes again, he will already be dead. He went to Newcastle and there was a haemorrhage in his chest and she never saw him again until the day they brought him back in his coffin and he didn’t much look like her father at all. They bury him and two days later Christine visits, an older Christine than she’s used to, fourteen or fifteen wearing clothes she stole somewhere, and she hugs her as she cries.)

*

She grows up, she finishes school. Christine comes four or five times a year and sometimes more and sometimes less and every one of her visits are precious, and every time she comes she is the same age as Ellie, give or take a year or two. It is like growing up with a special kind of cousin, with the dearest sort of friend.

She always knows Christine can never stay, knew that from the first moment when she was six, but it doesn’t stop something in her heart aching to keep her close, always.

She is sixteen when her mother dies.

She is seventeen when she almost marries a man. His hands are gentle and his kisses are sweet but there is a catch in his breath and sometimes he tastes of iron and salt.

It is foolish to marry someone known to be suffering from tuberculosis. She breaks it off and does not regret it because she was not really in love with him anyway, she only thought she was.

(There is something like love, budding deep in her heart, but every time she turns her eyes to it it feels like it might be crumble, so she does her best not to think on it, and on whose lips she longs to feel beneath her own, whose hands she wants to caress her thighs, whose hair she wants to kiss.)

(Tumbling blonde curls and smiling blue eyes and hands that are always soft, even wearing the most ridiculous of stolen clothes.)

Eoin tells her she should take up acting. It will be the last thing he tells her before he dies, the distortion of his spine gone into his ribs, eating into his lungs.

(Eighteen, just the same as her, and dead.)

She’s always fancied the thought of being a famous actress, like Clara Bow or Carole Lombard.

Christine tells her she thinks she would be marvelous, and smiles that smile that makes her heart flutter.

She goes to Dublin in 1933. She sleeps with a man and his touch is the wrong touch but her touches are right and he puts her on stage. Ellie sounds too sweet of a name, and Eleanor too serious, but there is Spanish on her father’s side, and her eyes are dark, her hair waving black curls, and there is the faintest cast to skin that means she has never been as pale as other girls.

She calls herself Sorelli, and smiles.

Two days later, she turns nineteen.

*

Christine comes ten times that year. She accosts her coming out the stage door and hugs her and the kiss she presses to her cheek makes Sorelli’s skin burn. That time she stays a week, and Sorelli introduces her as her cousin from Galway, and they go to dances and an opera and share the same bed, and Sorelli wakes in the night and looks at that pale face and thinks of reaching over and kissing her. Not the chaste kisses they’ve shared pressed to cheeks and foreheads, but a proper kiss, on the mouth. Those blue eyes would flutter open, those lips smile against hers, and Christine’s arms would draw her closer, her hands slip to curl around her hips…

She rolls out of bed and goes to the window and breathes slowly through her nose, willing her heart to settle, willing the ache to leave her chest and leave her be. She cannot love Christine, she cannot. How can she love someone who is always going to leave?

*

She is twenty when she meets Philippe. He is thirty and tall and broad, his smile bright and his touch gentle, and he kisses her without hesitation. It is three months since she saw Christine and they had a fight over something ridiculous, and she just needs someone, someone to touch her, someone to make her feel special because loving Christine is worse than a loving a ghost because loving Christine means she cannot speak a word of it.

His arms circle around her, draw her close, and his voice is low in her ear as he whispers, would you object…?

She dips her fingers beneath his waistband, brushes warm skin that sends a thrill through her for need, and breathes, not at all.

(He is the gentlest lover she has ever known, and one night becomes two, becomes a week, becomes a month, and they fall together without speaking of it, and are photographed in the society columns as Philippe de Chagny who might have been a Duke if his grandfather had not married a Catholic, and the famous La Sorelli, stepping out together…)

(It is love of a sort, this she knows. A love different from what she feels for Christine, a love very different from what she thought she felt for the man in Athlone. It is a love it would be easy to live in, and she has no doubt that Philippe adores her, and that adoration eases something inside that she did not know was aching, even as it makes the aching for a different pair of hands worse.)

(Christine comes at last, after six months, and there is something sad and drawn in her face to see Philippe, but she smiles for the two of them and says, I hope you’ll be very happy.)

*

Christine’s visits become rarer, two a year, maybe three. In the whole of 1937, she only comes once. It is easier this way, easier for Sorelli to pretend that the ache in her chest is simply for missing a friend, and nothing more. And if she sometimes dreams of playful kisses, of soft touches and curling blonde hair, then the face is sufficiently dim behind her eyes that she can pretend it is Philippe she dreams of.

(She wakes beside him, and sees the face she has resolved to love in place of another, easy and slack in sleep, and she kisses him and wonders if he can sometimes sense the secret that she keeps deep inside, if he might somehow know that her heart is not wholly his. Are her feelings a betrayal of him even if she never does anything about them?)

Her acting becomes dancing, takes her to London and to Edinburgh and to Paris, even, once, to Milan.

Paris she loves the best of them all. She goes for walks with Philippe and he buys her jewelry and hats and laughs as he kisses her and they eat in tiny little restaurants and nobody knows that he is the man who might have been a Duke and nobody knows she is the girl that appeared in Dublin one day without a history, and it is almost easy to pretend Christine is someone she simply dreamt about once.

(Almost easy, but never quite possible. Not when every blonde girl in the crowd or on the street makes something catch in her chest, and leaves her breathless.)

*

She turns twenty-four in the spring of 1938. There is a persistent pain in her left leg that she puts down to strain, to overwork, and the vigour of her nightlife with Philippe. She rubs in ointments but none of them take the aching away, and Philippe suggests maybe having an x-ray taken, but she puts it off.

And then she puts it off a little longer.

June comes, the first visit from Christine in fourteen months (not that she was counting) and this Christine seems older than her, seems closer to thirty than twenty-five, something severe and strange about her eyes, and she frowns to see the slight limp Sorelli has taken on.

“I think you should have an x-ray taken.” And something about it is meaningful, brooks not the slightest bit of reproach, as if she would say more, but the laws of time prevent it.

(Sorelli has long since learned not question Christine when she comes to visit, certainly not when she is older than her.)

She says she will, and then waits a month, because she’ll be damned if she lets anyone tell her what to do, even someone she has known eighteen years.

The x-ray shows tuberculosis in her femur.

The doctor is apologetic, tells her how she’ll have to lie up immediately with the leg immobilized, that even if it heals she might never dance again.

She feels only a deep spreading numbness.

Philippe cries when she tells him.

They spend a last night together, and her kisses are softer and gentler than ever.

*

The window beside her bed lets her see the moon. The cage they put her leg in keeps her from moving it at all. There are twenty more on her ward, girls and women both. The girl in the next bed is barely eighteen, another new admission, and has it in her spine. The cage they put her in lets her only move her arms.

A little girl dies of meningitis that first night.

*

Philippe brings her books and visits her every day, and still she is bored and lonely. She never knew how much she needed movement until she could not move at all.

The girl in the next bed gets a letter every morning from her sweetheart, a Trinity medical student, and he visits her every afternoon, his dark hair slicked back and his smile soft and slow, and the spectacles he wears as he reads to her don’t age him at all.

Sorelli feels fortunate that she, at least, can hug Philippe, unlike this Harrison girl and her boy.

Christine visits four times in the first week, ten times in the next month. It is the first time she has visited so often or so consistently, and she seems to have a reliable supply of clothes but there is always that strange sadness behind her eyes, and when Sorelli asks her of it she does not answer, only shakes her head.

The old love that has prickled in Sorelli’s chest threatens to flare back to life.

Her acting friends visit, one by one, early in her stay, consoling visits but shallow all the same, and they never come back. She only has Philippe and Christine.

They are the one bright point in her day, and Philippe makes sure to never miss a day.

(“Let’s get married,” he whispers, voice low in her ear, when she has been in four months, “when you get out of here.” Always when, always certain, and she is not despairing but sometimes she wonders if it should be if instead because the girl the other side of Harrison has been here seven years, but she doesn’t say that, instead she nods, and kisses him with tears in her eyes and says, “if you want to.” His laugh is sweet as he kisses her back. “Of course I want to.”)

Christmas is miserable but Christine stays with her all day and Philippe brings her a sketchbook and a pen and several pots of ink and tells her to write her story. (“Your history is more thrilling than mine.”) She would take him at his word, but she has no idea where to begin.

*

The ninth of March, and Philippe doesn’t visit.

The tenth, and no sign of him, and the fear in her heart is inexplicable and creeping as Harrison’s medical student glances at the still-empty chair by her bed, and something shutters behind his eyes.

The morning of the eleventh, and her visitor is not Philippe, not Christine, but Philippe’s younger brother, Raoul, a boy who is all of fifteen, who she has met only a handful of times, and then she knows.

She knows, and the pain that twists in her heart takes her breath away and brings tears to her eyes.

“How did it happen?” her voice is distant to her own ears, too-steady, and the tears trickle from Raoul’s eyes, his lips twisting.

“A bomb…his boat…” the boy’s face crumples, his voice chokes, and he bows his head but she cannot hear him weep through the rush of blood in her ears.

*

Was it that she didn’t love him enough? Was it the love for Christine deep in her heart after all of these years?

Was it just a twist of fate? Or a punishment for the sins she’s contemplated? A punishment for the straying of her love?

*

There are tears in Harrison’s eyes as she looks at her and says, “I’m sorry” and her medical student, when he visits, shakes her hand.

*

She is not allowed to leave her bed for to go to the funeral. She lies still all day and keeps her eyes closed through the whispers from the next bed, and she knows Christine comes to visit, she knows it, but she pretends to be asleep, and it is not that she wishes she could follow Philippe, more that she wishes she had never loved Christine, and eventually Christine leaves.

*

She visits again a week later, her face pale and drawn, but this time Sorelli acknowledges her.

She has had a lot of time to think, sitting here alone, a lot of time to think and piece things together and she has remembered the look on Christine’s face the first time she met Philippe, the mingled horror and surprise and her strained smile, and she has remembered the look that flickered in her eyes when she told her to have an x-ray, and the way she flinched when her visit collided with Philippe’s, two weeks before he died.

Too much time to think, and what she knows is deeper than the mingled guilt and grief in her chest.

“You knew, didn’t you,” and it is not a question, and it is barely an answer when Christine nods. “I never want to see you again.”

Christine nods again, and rises, and walks out.

Sorelli closes her eyes, and lies down, and at last gives in to tears.

*

In July, after a year, she is deemed healed.

The cage is taken off, she is given crutches and instructed to build the strength in her leg slowly.

Her first stop is Glasnevin, but it is impossible to look at the headstone, at the name Philippe Roderick de Chagny and the dates of 1904 and 1939 and believe that he is really there beneath the ground.

She leaves, and goes back to her old apartment, and vows never to visit again.

*

The war comes. She rebuilds the strength in her leg. She returns to the stage.

She takes tea with Raoul once a week because he asks her to, and they only sometimes talk of his brother, but she feels slightly less alone.

At night she sleeps alone and there are men who would take her into their beds, and women too, but she has no desire to look at any of them, all she wants is soft hands and blue eyes and blonde hair, be it long and curling or brushed back neat with that single lock falling over the forehead, and no one she sees is ever right.

No one is Philippe, nothing can bring him back and she knows that, she knows it, fuck but how she knows it, but none of them are Christine either.

A year passes before she begins, slowly, to regret her words.

*

She goes to London and works as a nurse by day and dances at night as the bombs fall, and dreams of kisses and soft touches but never seeks them out.

When people ask, she gives them cryptic smiles.

And she doesn’t know it yet, but someday it will be May of 1945, and she will have fulfilled what she considers her duty of keeping Raoul out of the war because the war will have ended and he will be studying history, and in the middle of the cheering crowd her eyes will catch a curl of golden hair and she will turn, her heart hammering, and she will meet a face she once told to go away, and she will remember nights of loneliness as she reaches out and takes a soft hand, she will remember mingled grief and guilt and two types of love living in her heart, and she will decide to hell with it, to hell with it all, to hell with always leaving and never staying and having no history, and Christine’s eyes will be wide with surprise, but her lips beneath Sorelli’s will be just as soft, just as certain, as Sorelli ever dreamed.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 7.29

587 BC – The Neo-Babylonian Empire sacks Jerusalem and destroys the First Temple. 615 – Pakal ascends the throne of Palenque at the age of 12. 904 – Sack of Thessalonica: Saracen raiders under Leo of Tripoli sack Thessaloniki, the Byzantine Empire's second-largest city, after a short siege, and plunder it for a week. 923 – Battle of Firenzuola: Lombard forces under King Rudolph II and Adalbert I, margrave of Ivrea, defeat the dethroned Emperor Berengar I of Italy at Firenzuola (Tuscany). 1014 – Byzantine–Bulgarian wars: Battle of Kleidion: Byzantine emperor Basil II inflicts a decisive defeat on the Bulgarian army, and his subsequent treatment of 15,000 prisoners reportedly causes Tsar Samuil of Bulgaria to die of a heart attack less than three months later, on October 6. 1018 – Count Dirk III defeats an army sent by Emperor Henry II in the Battle of Vlaardingen. 1030 – Ladejarl-Fairhair succession wars: Battle of Stiklestad: King Olaf II fights and dies trying to regain his Norwegian throne from the Danes. 1148 – The Siege of Damascus ends in a decisive crusader defeat and leads to the disintegration of the Second Crusade. 1565 – The widowed Mary, Queen of Scots marries Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, Duke of Albany, at Holyrood Palace, Edinburgh, Scotland. 1567 – The infant James VI is crowned King of Scotland at Stirling. 1588 – Anglo-Spanish War: Battle of Gravelines: English naval forces under the command of Lord Charles Howard and Sir Francis Drake defeat the Spanish Armada off the coast of Gravelines, France. 1693 – War of the Grand Alliance: Battle of Landen: France wins a victory over Allied forces in the Netherlands. 1775 – Founding of the U.S. Army Judge Advocate General's Corps: General George Washington appoints William Tudor as Judge Advocate of the Continental Army. 1818 – French physicist Augustin Fresnel submits his prizewinning "Memoir on the Diffraction of Light", precisely accounting for the limited extent to which light spreads into shadows, and thereby demolishing the oldest objection to the wave theory of light. 1836 – Inauguration of the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, France. 1848 – Great Famine of Ireland: Tipperary Revolt: In County Tipperary, Ireland, then in the United Kingdom, an unsuccessful nationalist revolt against British rule is put down by police. 1851 – Annibale de Gasparis discovers asteroid 15 Eunomia. 1858 – United States and Japan sign the Harris Treaty. 1862 – American Civil War: Confederate spy Belle Boyd is arrested by Union troops and detained at the Old Capitol Prison in Washington, D.C. 1871 – The Connecticut Valley Railroad opens between Old Saybrook, Connecticut and Hartford, Connecticut in the United States. 1899 – The First Hague Convention is signed. 1900 – In Italy, King Umberto I of Italy is assassinated by the anarchist Gaetano Bresci. His son, Victor Emmanuel III, 31 years old, succeed to the throne. 1901 – Land lottery begins in Oklahoma. 1907 – Sir Robert Baden-Powell sets up the Brownsea Island Scout camp in Poole Harbour on the south coast of England. The camp runs from August 1 to August 9 and is regarded as the foundation of the Scouting movement. 1914 – The Cape Cod Canal opened. 1920 – Construction of the Link River Dam begins as part of the Klamath Reclamation Project. 1921 – Adolf Hitler becomes leader of the National Socialist German Workers' Party. 1932 – Great Depression: In Washington, D.C., troops disperse the last of the "Bonus Army" of World War I veterans. 1937 – Tōngzhōu Incident: In Tōngzhōu, China, the East Hopei Army attacks Japanese troops and civilians. 1945 – The BBC Light Programme radio station is launched for mainstream light entertainment and music. 1948 – Olympic Games: The Games of the XIV Olympiad: After a hiatus of 12 years caused by World War II, the first Summer Olympics to be held since the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, open in London. 1950 – Korean War: After four days, the No Gun Ri Massacre ends when the US Army 7th Cavalry Regiment is withdrawn. 1957 – The International Atomic Energy Agency is established. 1957 – Tonight Starring Jack Paar premieres on NBC with Jack Paar beginning the modern day talk show. 1958 – U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower signs into law the National Aeronautics and Space Act, which creates the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). 1959 – First United States Congress elections in Hawaii as a state of the Union. 1965 – Vietnam War: The first 4,000 101st Airborne Division paratroopers arrive in Vietnam, landing at Cam Ranh Bay. 1967 – Vietnam War: Off the coast of North Vietnam the USS Forrestal catches on fire in the worst U.S. naval disaster since World War II, killing 134. 1967 – During the fourth day of celebrating its 400th anniversary, the city of Caracas, Venezuela is shaken by an earthquake, leaving approximately 500 dead. 1973 – Greeks vote to abolish the monarchy, beginning the first period of the Metapolitefsi. 1973 – Driver Roger Williamson is killed during the Dutch Grand Prix, after a suspected tire failure causes his car to pitch into the barriers at high speed. 1976 – In New York City, David Berkowitz (a.k.a. the "Son of Sam") kills one person and seriously wounds another in the first of a series of attacks. 1980 – Iran adopts a new "holy" flag after the Islamic Revolution. 1981 – A worldwide television audience of over 700 million people watch the wedding of Charles, Prince of Wales, and Lady Diana Spencer at St Paul's Cathedral in London. 1981 – After impeachment on June 21, Abolhassan Banisadr flees with Massoud Rajavi to Paris, in an Iranian Air Force Boeing 707, piloted by Colonel Behzad Moezzi, to form the National Council of Resistance of Iran. 1987 – British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and President of France François Mitterrand sign the agreement to build a tunnel under the English Channel (Eurotunnel). 1987 – Prime Minister of India Rajiv Gandhi and President of Sri Lanka J. R. Jayewardene sign the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord on ethnic issues. 1993 – The Supreme Court of Israel acquits alleged Nazi death camp guard John Demjanjuk of all charges and he is set free. 1996 – The child protection portion of the Communications Decency Act is struck down by a U.S. federal court as too broad. 2005 – Astronomers announce their discovery of the dwarf planet Eris. 2010 – An overloaded passenger ferry capsizes on the Kasai River in Bandundu Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo, resulting in at least 80 deaths. 2013 – Two passenger trains collide in the Swiss municipality of Granges-près-Marnand near Lausanne injuring 25 people. 2015 – The first piece of suspected debris from Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 is discovered on Réunion Island. 2019 – The 2019 Altamira prison riot between rival Brazilian drug gangs leaves 62 dead. 2021 - The International Space Station temporarily spins out of control, moving the ISS 45 degrees out of attitude, following an engine malfunction of Russian module Nauka.

1 note

·

View note

Text

First shift at the pool was a double. I started the day guarding with the palest, red head guy ever.

Lowell

Apparently he is in his late 20’s, done with college, an only child, who lives at home.

We guarded for the senior lap swim in the morning. He said it was one of the best shifts because it’s quiet and nobody bothers you.

I have no idea what he was talking about because three different times I about had a heart attack watching these seniors try to use the ladder to get into the pool or try to get into the pool using the lift.

Lowell explained to me that this pool is one giant high school filled with exes, hook ups, and gossip.

His best advice, “don’t date anybody you work with... especially here.”

Well at least he wasn’t hitting on me. That would have been awkward.

Senior swim ended and we had to prepare the pool for swim lessons.

The first lessons were the younger kids and only lasted 30 minutes. The next lessons after that were 45 minutes and for higher level swimmers.

I went into the locker room and met Maggie the next guard on her way out to relieve Lowell.

“Hey. You’re new here! I’m Maggie.”

“Stefanie. Nice to meet you.”

“See ya out there!”

She glided past me into the hallway of the locker room.

Maggie had jet black, pixie cut hair, and a tiny nose stud. Everything about her was cool. I always wanted a pixie cut. I think my face is just too fat for that though...

Don’t do anything drastic with your hair. You just outgrew that perm you and Nor thought was a great idea.

I ditched my shorts and tank, grabbed my towel, and headed back out to the pool.

Jeff was in now.

“Stefanie is new here. Be nice.” He shouted to all the staff and students waiting on the deck of the pool. I felt like a piece of meat before the lions.

Your first job... in a bathing suit. Could there be anything more confidence shaking?

I managed a wave. Geez. What an intro!?!

The first class I was paired with this guy Kevin. He sort of reminded me of that weird roommate in Friends that moves in with Chandler. Nice enough.

The kids were cute. I hated to admit it but this job was actually fun.

“You’re really great with the kids. How come I haven’t seen you around South?” Kevin asked as he shook the water out of his hair.

“I go to Montini. Lombard.” I shrugged.

“Cool.” I could feel his eyes move up and down my swimsuited body. I clutched my towel a little tighter.

I know what he’s thinking, “Catholic school girl... uniforms...” the whole shebang.

So typical.

I kept quiet and scooted off to the side while I waited to see who I would shadow in the next class.

0 notes

Text

“carole Lombard, Paulette Goddard, coy”

A soft has a crush on Myrna Loy, carole Lombard, Paulette Goddard, coy jean Artemisia strongest quell, the

gift thou were great gift of actresses glowing dew, and who quake. Is now teares: yet nevertheless still stop the rest,

resty Muse, my love hath power, if more covered and I rise nor scorpions—stifled the light The Sage— “oh Thou therefore I

decree the finger, but bind him rives horatian fame; in my arms with woman woos, what is knows, whose glaring;

and free, do easily seeking with my tattered coat?— Falsehood, in sun. A siren song, and sight there camst that coast,

am given its own. Thou didst thou m ade a face is burning field, into the ranckorous

sneer, point out arose, grapes or fruit might prove, wearing bloom is oer thy yeares a hostess demonstrous mountains, ye satyrs joyed with

this be never win the prime of thy hour surqedrie, with his chewed- off tail trains my young Daphnes

crowd. His desires have I heare torn in each tree again with us doth not my swan, my though evening; long