#Lecture Notes from 1783

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

© Paolo Dala

Scenes That Elevate The Mind

What are the scenes of nature that elevate the mind and produce the sublime sensation… the hoary mountain, the solitary lake, the aged forest and torrent falling over rocks.

Hugh Blair Lecture Notes from 1783

#Hugh Blair#Lecture Notes from 1783#Water#Ocean#Beach#Sea#Nature#Black and White#Gulf of Leyte#Guiuan#Eastern Samar#Philippines

0 notes

Text

|| A Harvard Undergrad Becomes Delusional and Has Vivid Hallucinations of the American Revolution: Chp 1 ||

Synopsis- a Harvard Undergrad becomes delusional and has vivid hallucinations of the American Revolution

Note- i like. history

----------------------------------

“The American Revolutionary War lasted from 1775 to 1783, whereby the Thirteen Colonies secured their independence from the British Crown and consequently established the United States as the first sovereign nation-state founded on Enlightenment principles of the consent of the governed, constitutionalism and liberal democracy--”

The pages turn.

“In late 1774, in support of Massachusetts, twelve of the thirteen colonies sent delegates to Philadelphia, where they formed the First Continental Congress and began coordinating resistance to Britain's colonial governance--”

The pages flip.

“In the summer of 1776, in a setback for American patriots, the British captured New York City and its strategic harbor. In September 1777, in anticipation of a coordinated attack by the British Army--”

The book slams shut.

Dropping my head against the cool marble table, I shut my eyes and slump. Hours of studying left me with a raging migraine, an empty mind, and one too many paper cuts. I was exhausted in ways only studying could afflict a person and I cursed myself for my ability to blank out when important information was recited to me.

If only I could pay attention during lectures. If only I could focus on the rolling waves of words on the glaring, glossy sheets of textbooks. I breathed out heavily. If only. Sadly the world said “fuck you” and fucked I am.

Peeling my eyes open, I stared blankly at the portrait of Charles C. Pinckney I came to despise seeing day after day and debated whether or not I should call it quits or push through researching for that damned paper. Quickly, I opted for the former. I sighed. Three hours was good enough for today.

The Boston Public Library was both a blessing and a curse. A blessing, because I have access to all kinds of documents on America’s history. A curse, because I have access to all kinds of documents on America’s history. There was a sort of obligation to write about it, especially since I was at the heart of the Revolution, the home of Hancock and Adams, and also because I assumed it would be far easier than it was.

I dragged my head to look at the shut textbook and felt my heart crumble. This will be the death of me.

But if I can prolong such death, then I shall. I sat up, stretching my cramped bones, and shoved away the awful books before pushing myself up and throwing on my bag, wincing. The weight of my bag crushed the knot of stress on my shoulder blade, sending an aching pain down my back. I groaned rolling my shoulders while wishing I could snap my arm off to give myself relief.

Maybe someone in the library would just walk up to me and rip it off, but until that day comes I’ll settle with endangering myself with exploration. Giving one final stretch, I began to make my way out of the ancient marble library.

---

Boston. Boston, Massachusetts. A place deeply ingrained in good old American history from massacres to floods of molasses and my personal city-wide jail cell. As unfortunate as it is to be trapped, it could’ve been worse. I shudder to think what would’ve happened if I had gotten caught in a Chicago or New York tar trap.

I push through the ornate, metal doors of the library and out onto the streets of Boston, beginning the familiar walk to the apartments. Traversing through streets of old and new, there was a certain sense of deep familiarity. It was another lucky thing about Boston being my jail cell.

I only moved here a few months ago and usually one would be stiff and awkward in a place far, far away from their origins, but seeing those brick buildings and cobblestone roads hidden by those of steel, glass, and concrete, I adjusted unexpectedly easily.

Not that I was an inflexible person in general. I’ve had my fair share of traveling every which way, up and down and across the country, staying in brief intervals with restlessness plaguing my every action. No, this was different. How or why, I’m not entirely sure, but I think it’s nice.

Seeing the park centered on Commonwealth Avenue, I sped up and turned onto my side of the street, working my way around tourists and neighbors and crossing over the bustling traffic. Occasionally I gave a quick, polite smile to someone I accidentally made eye contact with, before continuing onwards.

It’s going to be a quick stop at the apartment, grab my gear, and go back out again just before the sun begins to set. A grin makes its way to my lips and a burst of speed pushes me forward. Danger is my happy place.

I arrive in front of my apartment building and quickly walk in, flying up the stairs, before pushing into my section. Throwing my work bag onto the dingy couch I sped into my room, quickly changing and grabbing my gear, listing them off in my head; pants, shirt, jacket; goggles, respirator, gloves, headphones, charger, cash, first-aid, phone, camera, put them in my bag.

I rush back into the living room and throw on a pair of boots. With a satisfied smile, I threw on my bag feeling the knot easing, and back out the door I went. I passed by another neighbor, giving her a little wave and smile. She smiled back and I flew back down the stairs to the edge of the street to hail a taxi. This is my kind of relaxation.

---

The barn door is ripped open. The hinges cry out, still weary of being used after nearly two centuries of slumber, but they’ll get used to me. They will.

A puff of dust bursts free from the idle inside and breezes past me, some specks brushing against my respirator and goggles. With ease, I waved the dust cloud away with my glove-clad hand, and casually walked inside as though this was my real home.

I discovered the old barn around the time I was brought to Boston when I had attempted to make a break for it.

I just ran. And ran. And ran. Until I came upon this decrepit forgotten beat-up barn in the middle of a field only a couple of miles away from the edge of Boston and it surprised me, I won’t lie, with how praise-heavy of history the city was. You assumed that everything within 100 miles of the city would be tended to with major tender loving care, but that was clearly not the case for my darling broken barn.

And so the only sensible thing to do with such a discovery was claim it as mine! So I did and obsessively explored every single crook and corner to my heart’s content. I had no clue where such adoration for the old building came from, but I didn’t give two shits. It was mine and I was its.

Owner.

Unofficially.

No, I’m not weird.

I made it in the nick of time, arriving just as the sun started to journey its way to the other side of the world to ruin someone else’s sleep. I brought out my stolen 55-dollar flashlight and flicked it on. A good beam of light lit the dusty barn, waking up the sleepy nats that tumbled around in the glow. Time to get cracking.

Throwing on my headphones, I ambled deeper into the barn with a hand trailing lightly on the grooves and ridges of the splintered, ancient planks.

Each step I made was delicate and calculated, feeling each pebble and speck of the uneven ground of dirt and old hay left behind centuries ago. But no matter how much I tried to feel, there was a distance between me and the old barn, easily kept with the heavy protection and gear of my time. And I was far too lazy to take it off; a subconscious fear of accidentally destroying something or something destroying me. Like lead… or traps.

I shook my head, quickly skipping the sad song into punk rock. What the hell was all that moaning and groaning about? I dragged a quick hand over my mask and goggles and picked up the pace to move farther back into the barn, the flashlight staying steady and bright as ever.

I began to berate myself until I saw the ground looking far closer than it should. A shock of panic shot through my chest and I threw my hands in front of me to brace for the brutal impact.

And brutal it was.

I collided onto the jagged gravel and landed with a heavy thud. I could feel the ragged ground scrape against me and I clenched my eyes shut, groaning, the sound muffled by the mask. My arms and stomach ached and burned with a thousand tiny rocks embedded into my clothes and skin scrapes on my knees. I had tripped on… something.

My confidence was hurt the most, not that I had any in the first place, and absolute embarrassment burned fiercely in my chest. Ugh, I felt stupid. Scrambling up from the ground, I dusted off the pebbles and dirt on my now dust-stained jacket, before scooping up my fallen flashlight. I shook my hands loose and adjusted my skewed headphones. Ugh, I felt really stupid.

I pivoted to look back at what damaged my self-esteem, pointing my flashlight at the ground. The light illuminated the drag marks in the dirt from my fall and the hay pushed away from the force and… oh?

A small rusted knob stuck out from the ground, now freed from the years of dirt that built up with the help of my fall. Creeping closer, I crouched down, reached a hand towards it, and began to brush away the rest of the dirt.

Immediately I felt a difference. Below the dirt wasn’t more dirt, it was something else. I placed my flashlight on the floor beside me and a shiver of excitement rushed down my spine.

Adventure.

Brush by brush, I could make out strips of wood that were embedded into the dirt floor, and with one last stroke, a trapdoor was revealed. I leaned back onto my knees, gazing at my discovery in awe. I grinned. Oh, hell yes.

It took far longer and far more strength than I had expected to get the door opened. Shockingly, It was worse than when I tried to pry open the barn door for the first time. All I could imagine was all the grime, mud, and paint stuck deep in the hinges and grooves that mixed themselves into a superglue, refusing to let just anybody in like some dirty glue guardian of secrets.

Luckily, I’m far more unwavering than some false glue and pried that sucker open with pure strength. And a stick. I couldn’t help that swell of pride that blossomed once I was showered in a puff of ancient dust that wooshed freely after being trapped for who knows how long. Hopping on my toes, I nearly leaped into the void of darkness that was the crypt without precaution.

I managed to reel in my enthusiasm and picked up the flashlight before I directed the beam into the hidden cellar. The shining light revealed some highly suspicious-looking steps that led deeper in, all rotted and splintered and utterly unstable.

Immediately, I stepped in and made a quick descent into the basement, ignoring each creak, groan, and shudder from the steps before landing on a dirt floor. I paused my music and pushed down my headphones, gazing in wonder at my discovery.

It was like a pause in time, a portion of history untouched and kept secret. Shifting the flashlight’s beam over the small room, I drag my eyes across every square inch of the cellar. Over every cracked pot, crooked shelf, shattered counter, rickety wooden table littered with old parchment, and every single speck of dust. It was beautiful.

I crept towards the table that sat back against the room, an intense pull of curiosity filling my veins and I stood before the collections of yellowed paper. My heart began to pound the moment I caught a glimpse of the faded stains of ink that swirled on the pages. A long-kept secret for more than 200 years, just inches from my hands.

Fuck yeah. I reached for a page and with the most delicate of touches, lifted it from its dust-framed seat and slowly brought it close.

The thought of accidentally damaging it in some way screaming in my head for brief seconds was not enough to deter me and so, with the flashlight held beneath it, I read the date.

April 1st, 1774--

Suddenly, I was thrown into darkness, pitch black filling my senses. I flinched nearly, dropping the paper and flashlight, as I stumbled back in surprise. What the hell?

I quickly and delicately placed the piece of paper down on what I hoped was the table and frantically shook the short-circuited torch. Mumbling hisses and curses at the thing, I desperately flicked at the switch hoping for something, a flicker of light, anything. I gave it another shake to no avail.

Nothing.

“Oh fuck…” I breathed out, muffled from the labor of my breaths and doused in panic. Fifty-five dollars and it already busted. I paused for a brief moment. That means I was perfectly justified to steal it, I shoved it into the pocket of your bag, it was a scam.

I continued to step back, hesitantly triple-checking each step that was placed. The last thing I wanted to do was trip again in the black void and possibly bust my head open on some rogue stone. Taking a few more steps back, my heel hits the back of what I hoped was the bottom of the stairs and I pivot to face it, leaning forward to lay my hands on the wood plank, before crawling up the stairs on all fours.

I’ll come back. I swear it. But exploring abandoned places with no reliable light source is stupidly dangerous and not the kind of danger that’s relaxing. So much for police-grade utilities, cheap bastards.

Also, the dark is scary.

Each step was a drag and I felt a weight sink in my limbs as I slowly made my way out of the cellar. The darkness was deafening and heavy, weighing down upon you.

Weird, I thought deliriously as I made another slow step up. My eyes started to droop and began to stumble, my head whirling and swooning like I was stuck on a rocket-fueled turn-table ride. I take another leaden step. I was getting closer. And with another step, my head hits the trapdoor.

Sighing, I placed my hands on the door and pushed up.

Instantly I’m blinded, a piercing white light burns into my eyes and I yelp, yanking back into the darkness.

I slapped a palm against my eyes and cursed as a tearing pain streaked across my forehead from the intense light while my ears began to ring. Gritting my teeth, I rub at my burned eyes. What in the world is going on out there, did someone bring floodlights to the barn?!

Squinting my eyes, I climb back out the trapdoor, facing the full force of the light as the ringing grows more shrill. I wince and put a hand out against the radiant beam, finally stepping onto the barn floor.

The ringing ceased. The light faded. Rapidly blinking my burned-out eyes, my vision began to clear and soon what I saw left me thunderstruck.

The barn looked… different. New, as though it was just built from freshly chopped trees, free from any stains, chips, and rot. The musty scent of age was gone, filled with the fresh breeze of newly laid hay. Not only that but it seemed to be smack dab in the middle of the day. The sun’s light breached through the openings between the wood planks and settled its glow in the barn. I furrowed my brows as I looked around the barn I swore I knew. I couldn’t have possibly been in the cellar that long for it to be day.

I swiveled back to look at the opened cellar door and quickly leaned over to shut it, before stepping back and staring at it. Darting my gaze between the trapdoor and the brightly lit new barn, I grew more confused by the second that I pulled off my hood and lifted my goggles to rest on my forehead to get a clearer look at the place. I needed to see I wasn’t losing my mind, and yet the barn still looked new.

Slowly, I nodded and started to accept that maybe I was far more oblivious than I already believed I was and that this barn took it to a whole other level. I waded through the new heaps of haystacks, deciding that I should go back to my apartment and book an appointment with the eye doctor, as soon as possible.

Sliding the barn door open with surprising ease, I tumble out into the open nearly slipping on some mud. A quick leap of my heart made me see the heavens for a split moment before I came back down to face with a horse.

I stared and the horse stared before it tossed its head as it stepped back and to the rest of its fellow equine. To say I had questions would be an understatement. There were never horses nearby, the barn was abandoned. At least that’s what I thought. I needed to go home. Immediately.

Quick as a skittish mouse, I ran down I supposed-to-be familiar path back to the lone tar road that I could follow into Boston. But I paused as I arrived next to the tree that marked its location.

It wasn’t there.

I stared at the wild shrubs and tall grass that covered the unfamiliar land. Why isn’t it there? My gaze darted along each pebble, leaf, and stick. It should be here. There’s no reason why it shouldn’t be here. Slowly, I began to run down what I hoped was the path of the vanished highway only to come across more shifts throughout the area.

Missing roads and metal signs, new wooden fences, narrow dirt roads, far more flora, and a disturbing absence of noise replaced by the deafening sounds of the air and birds. Everything felt different. Everything was wrong.

Every once in a while I would stop and turn in circles trying to find that specific marking on my mental map to find absolutely nothing before continuing to run in what I hoped was headed in the right direction. But as I sped on, it only became more apparent that I must’ve made a wrong turn.

I should at least be able to see the industrial towers and the outskirts of the city line, but nothing. There was nothing. I wasn’t sure how to feel as I slowed down to let my feet mindlessly guide me through the wilderness.

I’m… confused. Which isn’t much of an improvement, but it’s better than nothing. I don’t know where I am, I don’t know what happened with the barn. I wished I had something that could conveniently tell me where I was and guide me back with the safest and fastest route it could provide. A heavy pail of realization tipped down onto my head.

Oh, yeah. I have a phone.

I slid my bag to face my front and quickly snatched my phone from the designated phone pocket. The bag fell back and I opened my phone to Google Maps, glancing at the bars. Only one, that’s fine. I looked back at the screen and sighed, seeing it frozen. It’s not fine. I shut off my phone and shoved it into my jacket pocket, trudging on.

And with that, only one little thought circled my mind: I’m lost.

Somehow, some way, I got lost. I had no clue what happened with the barn, no clue where I was, no clue where everything was, and by golly, did I want to drop to the floor and roll around in the grass. But I didn’t. I put one foot in front of the other through the shrubs and the dirt as the sun shone obnoxiously through more trees than I’ve ever seen near a city such as Boston.

One foot forward, the other followed, a part of me refused to acknowledge my situation fully and was perfectly content to walk mindlessly through the foreign world. One then the other, one then the other, a nice smooth walk through the lovely forest that I chose to walk through. One then the other, oh, are those buildings?

Squinting, I peer at the curved silhouettes that stand apart from the natural forms of the flora that scarcely surround them. Have I finally made it back to Boston? They don’t look like those on the outskirts, though. Perhaps I arrived from a different direction. I lift my head and stare at the pale blue skies. Yes, a different direction, at least I’m back home.

Back home, indeed.

Stumbling closer to the buildings, I come across a dirt road I’ve never seen before that seemed to lead into the city. I ignored the tracks of hooves and parallel streaks and walked along the edge, unclipping my respirator to hang from my other ear. Soon, I began to hear the faint hustle and bustle of people being people and the city going on with its busy life. A cool sense of relief washed over me, but I couldn’t help but furrow my brows as I listened closer to the noise. It didn’t sound… right.

A chill trickled down my spine and I stopped. Something isn’t right. I’m not supposed to be…

Suddenly I became aware of the creaks and rattles of metal against wood trembling over the uneven dirt road from behind me at an alarming pace. My eyes popped open in panic and I scrambled away from the road just before I was hit by a gust of wind as something whisked past me. Alarmed I whipped around to see what could have possibly been hurtling down the road only to stop and stare in disbelief.

It was a cart. With horses.

A cart like those that are displayed in the halls of museums, all broken and rotten and barely living in the 21st century. But rather than the cart crumbling at the mere breath of a butterfly, it rolled on, built brand new with fresh wood like the barn, and carrying large wooden crates stacked heavily atop each other.

The wheels were coated thick with mud and pebbles which left behind indents in the dirt, adding to those already printed into the ground. It continued its journey, clearly heading towards the city and oblivious to the pedestrian it nearly hit.

And I could do nothing but follow after it.

--------------------------------

More Notes- wheeee

#amrev#turn amc#turn#america#turn: washington's spies#washington#1776#1776 musical#fanfic#george washington#Killme#time travel#fix it#benjamin tallmadge#alexander hamilton#Hamilton#britain#harvard#Boston#1773#18th century#Turn x reader

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lecture Notes MON 19th FEB

Masterlist

BUY ME A COFFEE

The Academy and the Public Sphere 1648-1830

Further Reading: Johann Joachim Wicklemann (1717 - 1768) from Reflections on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture

Antonie Cotpel (1661-1722) on the grand manner, from 'On the Aesthetic of the Painter'

Andre Felibien (1619-1695) Preface to Seven Conferences

Charles Le Burn (1619-1690) 'First Confrence'

More and Other

The first Academies start in Italy and then begin to spread throughout Europe. However, in this lecture we mainly focus on Paris and London. The Louvre palace, where the royal academy started, was where artists established there thought themselves as elites due to being part of the court, near the ruling and partly due to monetary reasons. (Remember: French Revolution 1793)

Now the other place was the RA, or Royal Academy in London was established to promote art and design (not to be confused with the Art and Design/Craft Movement of 1880-1920). Which focused on displaying and teaching painting and sculpture, only sometimes exhibiting drawing. If your work was exhibited, it was seen as being awarded the highest status and praise.

Jean-Baptiste Martin, A meeting of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture at the Louvre Palace, 1712-1721, Musée de Louvre

Although the academies had strict teaching rules and students had to follow. Which meant that art during this time and created by these artists had a regulated style.

While the French salons/academies had no entry fee when they exhibited the work (bi yearly), the British did have a fee of one shilling to view the exhibit (yearly), despite trying to advertise and claiming any person was welcome. When asked and confronted about the fee, they claimed it was to keep out “improper persons” (the poor).

A selection of Art Academies:

The Academia di San Luca, Rome, 1593

The Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, Paris, 1648

The Akademie der Künste, Berlin 1696

The Royal Danish Academy of Portraiture, Sculpture, and Architecture, Copenhagen, 1754

Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, 1688/1701/1725

Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid, 1752

Imperial Academy of Arts, St Petersburg, 1757

The Dresden Academy of Fine Arts, 1764

Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, Stockholm, 1766

Royal Academy of Art, London 1768

The Academy of San Carlos, Mexico, 1783

Royal Arts Academy in Düsseldorf, (1777) 1819

Academia Imperial das Belas Artes, Brazil 1822 (based on an earlier institution)

Martin Ferdinand Quadal, Life drawing room at the Vienna academy, 1787

United in Guilds, mechanical and practical artists wanted to be recognised as artists from a scoio, utility aspect. Painting and sculpture were valued in liberal and intellectual arts.

At the beginning of the 17th century, most painters were part of the Maîtrise de Saint-Luc, a guild founded in 1391, which controlled the market and sanctioned the method of training artists by apprenticeship.

A group of artists, including the young Charles Le Brun, sought to the escape the Masters and placed themselves directly under the protection of the young King Louis XIV, who was capable of removing them from the constraints of the guild. The Academy was established in 1648.

In 1655 letters patent granted the new company the right to call itself the The Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture) and decreed that only its members could be painters or sculptors to the king or queen. The Academy moved to the Louvre, where the Galerie d'Apollon hosted the reception pieces (chef-d’oeuvre), works that had to be performed before being approved and then elected an Academician. It oversaw—and held a monopoly over—the arts in France until 1793. The institution trained artists.

Perspective view of the hall of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture at the Louvre in Paris: [print].

Sir William Chambers, Somerset House, Now the Courtauld Institute of Art and Gallery

In 1768, architect Sir William Chambers petitioned George III on behalf of 36 artists seeking permission to ‘establish a society for promoting the Arts of Design’. They also proposed an annual exhibition and a School of Design. The King agreed and the Royal Academy of Arts, the Royal Academy Schools, and what you know today as the Summer Exhibition were established. The Royal Academicians were first based in Pall Mall, renting a gallery 30 feet long.

In 1775, Sir William Chambers won the commission to design the new Somerset House as the official residence. The Exhibition Room was 32 feet high and situated at the top of a steep winding staircase, it was described by contemporary literary critic Joseph Baretti as ‘undoubtedly at the date, the finest gallery for displaying pictures so far built’.

In the 1830s, the Academy moved to Trafalgar Square to share premises with the newly founded National Gallery, moving again in 1867 to Burlington House.

Summer Exhibition have been held every year since 1769.

Attributed to George Shepherd, The Hall at the Royal Academy, Somerset House, 1 May 1810

Before the establishment of Academies and their own openings to the public, there is no or very little actual documented art exhibitions and if there were any they were not documented. Or permanent.

These exhibitions and academies open art to the public, and gain a wider audience, mostly of the Bourgeois, who also usually commissioned the artists of the academy. Or the state did and the church – which was most common. But now individuals could now own art, which commodified art and created private ownership. This also was spurred on by art being more mobile, being painted on canvases which were easier to transport (in some cases).

The idea that came from this was: “art should be affordable”.

Another thing that came from exhibitions and wider audiences was that art became democratised, leaving it open for criticism and interpretation. Although the interpretation aspect wouldn’t be explored till around the 19th century, on wards really.

Teaching at the Academy

The Academy laid down strict rules for admission and based most of its teaching on the practice of drawing from the antique and the living model to support its teaching method and its artistic doctrine. Great importance was also given to the teaching of history, literature, geometry, perspective and anatomy.

In controlling education, the Academy regulated the style of art.

Professors of the Academy held courses in life drawing and lectures where students were taught the principles and techniques of the art. The students then looked for a master among the members of the academy, to learn the trade in their workshop. Only drawing was taught in the Academy and artists learned painting in the studios of the master, often working on his (rarely her) work.

(Left) Antoine Coysevox, Bust portrait of Charles Le Brun, Marble (Right) Charles Le Brun, The Family of Darius before Alexander, c.1660, 164 x 260 cm

Charles Le Brun became director in 1663 and was appointed chancellor for life. The Academy was administered by a director chosen from among its members, often the King’s favoured artist.

The sketch and finish

Le Brun introduced the sketch (esquisse) to French artistic practice, where it became central to the painter’s training in both official and private academies.

The esquisse was typically a small-scale, rapidly executed work intended to preserve an artist’s première pensée, or initial conception, of a subject. It elaborated composition and colouring, avoiding detail in favour of loose forms and fluid brushstrokes.

These studies were not for exhibition, and exhibited works were expected to be highly finished, often with glassy surfaces and the elimination of brushwork.

During the later eighteenth century some began to see merit in the sketch itself, but it was in the nineteenth century with Romanticism that an ‘aesthetics of the sketch’ really developed. In the 1830s sketch came to be identified with originality and genius.

Pierre Charles Jombert, Punishment of the Arrogant Niobe by Diana and Apollo, 1772, Oil paint on canvas, mounted on board, 35.7 x 28.1 cm, Metropolitan Museum, New York

The notion of aesthetic begins developing at the time, since the academies had a monopoly on aesthetic, they chose what they liked and didn’t. Their control on who was displayed in exhibits, could ensure an artist’s success. Rejection from and by the Salons was seen as the highest insult to an artist (and their aesthetic).

In the early nineteenth century the Academy instigated landscape sketch (études) competitions.

(Left) Pierre Henri de Valenciennes, The Banks of the Rance, Brittany, possibly 1785. Oil on paper, laid down on canvas, 21.3 x 49.2 cm. (Right) Théodore Caruelle d'Aligny, Landscape with a Cave, mid-1820s, Oil on canvas, 62.2 x 45.7cm

Here the importance of studying nature directly was emphasised through the practice of making plein air études, or small studies painted outdoors. Études generally did not serve as compositional models for particular paintings. Rather, these studies of different kinds of terrain and effects of light would be idealized or embellished by classically trained painters in landscapes produced entirely in the studio. From the time of Romanticism on, the sketch aesthetic became more-and-more central, but this was anathema to academic artists.

Exhibiting

In 1667 that the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture held the first semi-public show to display the works of its students considered worthy of royal commissions, laying a foundation the “group exhibition”. It was held in the Palais Brion in the Palais-Royal.

In 1725 the Salon moved to the Louvre and in 1737 exhibitions were opened to the public.

From 1748 group of Academicians formed a jury determining which works would be exhibited and where they were to be positioned. In 1673 the first catalogue (livret) was published. It was unillustrated until 1880. Exhibiting at the Salon was a condition of success.

Nicolas Langlois, Exhibition of works of painting and sculpture in the Louvre gallery in 1699. Detail of an almanac for the year 1700 – Etching and burin.

(Left) Giuseppe Castiglione, View of the Grand Salon Carré in the Louvre, Oil on Canvas, 1861 (Right) Alexandre Jean-Baptiste Brun, View of the Salon Carré at the Louvre, c.1880, Oil on Canvas

Key information:

France: The Louvre Palace, and other locations otherwise referred to as the Salon(s). The bigger the picture was the higher it was hung. The better and more favoured the artist the higher it was hung. Paintings of historical events were favoured and hung at the very top, all other lower in a specific order descending.

London: Portraits were positioned higher, gallery walls were still crowded all the same with frame to frame hanging, with no caption. Although you could purchase a booklet with all information and extra definitions. While there appeared less hierarchy in the London exhibitions, it still persisted just in a different form. Favoured artists got to choose where their paintings were hung. Even going as far as to developed an insult for paintings being hung so high: “the painting was skied”.

Hierarchy of genres

Inherited from Antiquity and codified in 1668 by André Félibien, secretary of the Academy, the hierarchy of genres ranked the different genres of painting assigning higher and lower significance.

At the top was history painting, called “le grand genre’: often large paintings, with mythological, religious, or historical subjects. Their function was to instruct and educate the viewer. Its purpose was moral instruction.

Portraiture, depicting important figures from the past as well as the present.

Genre scenes, the less ‘noble’ subjects: representations, generally small in size, of scenes of daily life attached to ordinary people.

The so-called ‘observational’ genres of landscape painting, animal painting and still life.

Other genres were added, such as the gallant celebrations, in honour of Antoine Watteau, which did not, however, call into question the hierarchy.

These academies were called chaotic by critics, and kaleidoscopic.

Examples of outliers:

(Left) Paulus Potter, The Bull, 1647 - 3.4 metres wide. An unusually monumental animal painting that challenges the hierarchy of genres by its size (Right) Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Marriage Contract (The Village Bride), 1761, oil on canvas, 92cm x 117cm. Musée du Louvre

These paintings also challenged the hierarchy of the Salon: it shows a scene that anyone could recognise.

This hierarchy was underpinned by the Ideal and the Liberal Arts.

Giogioni, Frieze in the main hall (detail), Fresco, Casa Marta, Castelfranco Veneto, c. 1510

From the Renaissance onwards artists conducted a campaign to be recognized as gentlemen, rather than workers or craftsmen. This centred on a distinction between the Liberal and the Mechanical arts.

The Liberal Arts were divided into the trivium - Grammar, Logic and Rhetoric - and the quadrivium - Geometry, Arithmetic, Astronomy and Music.

These involved imagination and intellect and were suitable activities for gentlemen.

In contrast, the Mechanical Arts were said to involve mere repetitive copying. These were activities conducted by workers and were often called ‘servile’ or ‘slavish’. They were deemed ‘mindless’ and demeaning to gentlemen.

Since the academies were open to not gentlemen, it was still believed they upheld class divisions. Examples of an artist from a lower background who rose through the ranks: J. M. W. Turner.

Ideal

Academic art, therefore, emphasised imagination and idealization and opposed copying things as they were. Abstract and mental properties were most valued. For instance, drawing was thought more important than colouring, which was often seen as superficial and feminine (cosmetics). Rather than copy a single figure ideal beauty was to be composed from the ‘best’ elements of multiple figures.

The nude was deemed more suitable, because modern dress was seen as ugly and ephemeral. Some thought the male nude more ideal.

In some senses this is a neo-Platonism, where ideal form exists in the mind of a divinity and things in the world are merely inferior copies of that ideal.

A second-century Roman marble copy of a Greek statue of Aphrodite, the goddess of beauty, crouching naked at her bath.

(Left) Artist Copying a Bust in the Royal academy at Somerset House, c.1780, Watercolour (Right) Academies and art schools had large collections of plaster casts made from antique sculpture.

The lower genres were thought to be too close to mechanical copying, whereas history painting involved imagination, intellectual learning and work with the ideal figure. This is complex because Academic artists and theorists rejected originality for adherence to principles and precedents.

Some important studies:

David and His School

J-L David, The Lictors Bring to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons, 1789

David was a member of the Jacobin Club and friend of Robespierre. He signed the death warrant for the King. With the fall of the Jacobins he was imprisoned and his life endangered. His paintings were very open to interpretation so upper and lower classes to understand and infer meaning from them, he also had political messages in his paintings. Although quite ambiguous, it engaged in emotions also over morality like usual historical paintings.

David’s austere student Wicar suggested that landscape painters should be executed.

Jacques-Louis David, The Death of Marat, 1793, Royal Museums of Fine Arts, Brussels

Painting around this time was developing Spectacle, as a primary focus to engage people’s emotions, and a shared emotional aspect rather than just class. The Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture was suppressed by the Convention at the request of David (August 1793) and it was in 1796 that the School of Fine Arts was founded. In 1816, The Bourbon Monarchy restored the title ‘Academy’.

In the middle of the nineteenth century Hogarth came to be seen as the founder of the British School.

Beer Street and Gin Lane, engraving, 1751

The Public Sphere

Habermas: ‘The bourgeois public sphere may be conceived above all as the sphere of private people come together as a public; they soon claimed the public sphere regulated from above against the public authorities themselves, to engage them in a debate over the general rules governing relations in the basically privatized but publicly relevant sphere of commodity exchange and social labour.'

At the Margins

Johan Joseph Zoffany, The Academicians Of The Royal Academy 1771-72, Oil On Canvas, 101.1 X 147.5 cm

Within this painting there are two paintings on the right most side, two busts of women. These are the two female founders who were not actually allowed in the Academy. However, that’s not to say that women weren’t painting and hosting their own private events, even if they couldn’t be critics and artists academically, so they easily fell into obscurity.

Republican Madame Roland

Feminist historians have suggested that the Salons hosted by women were an essential part of this culture of debate.

In 18th century France, salons were organised gatherings hosted in private homes, usually by prominent women. Individuals who attended often discussed literature or shared their views and opinions on topics from science to politics. The different Salons belonged to artistic and political factions.

Elisabeth-Louise Vigée Lebrun, Self-portrait in a Straw Hat, 1782

#art gallery#art#writing#art tag#artwork#paintings#essay#art show#art exhibition#art history#ms paint#painting#france#paris#salon#beauty salon#drawing#drawings#sketch#sketchbook#writers#writers and poets#writers on tumblr#creative writing#writeblr#writerscommunity#writer community#writers block#female writers#writer

0 notes

Text

Was Naturalist Rafinesque Cincinnati’s Most Bizarre Visitor?

In the strange convolutions of time and fame, we find millions of monuments to Constantine Samuel Rafinesque embedded throughout the hills of Cincinnati. They are tiny monuments – the largest not quite three inches across – but they are innumerable, and they are 450 million years old.

Rafinesque’s “monuments” are the fossil shells of the genus Rafinesquina. The scientific name means “Rafinesque’s shell.” The fossil was named in 1892 to honor a most eccentric naturalist, a scientist so unconventional that many of his colleagues considered him insane.

When he was born in Istanbul in 1783, he was given the name Constantine Samuel Rafinesque-Schmaltz, the “Schmaltz” inherited from his German mother and dropped from his professional name. His father was a French merchant who died when Constantine was 10 years old. Constantine followed his father into business and became so successful that he retired at 25 and emigrated to the United States.

Completely self-educated, Rafinesque established himself as a botanist of some note, but his interests ranged widely, from paleontology to religion to linguistics and anthropology. He wrote a 300-page monograph on the fishes found in the Ohio River and hung out for months with John James Audubon, learning about birds. Audubon pranked his peculiar houseguest by regaling him with descriptions of imaginary creatures. Rafinesque dutifully published scientific papers on all of them, including the 10-foot-long “Devil-Jack Diamond” fish equipped with bullet-proof scales.

Rafinesque was a tireless networker. He visited and corresponded with anyone interested in natural history, including President Thomas Jefferson. So many letters flew between America’s president and the pioneer naturalist that they were eventually collected in a book.

His travels frequently took Rafinesque through Cincinnati, where he lectured at Joseph Dorfeuiile’s Western Museum – predecessor of today’s Museum of Natural History & Science at Union Terminal. Cincinnati loved Rafinesque; he was the subject of a toast during city-wide Independence Day celebrations in 1827. He consulted with John C. Short, a North Bend farmer and dedicated amateur naturalist who accumulated an extensive collection of plants and fossils. According to biographer Edward Mansfield, some of Rafinesque’s more ingenious ideas were ignored by stolid Cincinnatians:

“Professor Rafinesque proposed more astonishing things—among other things, to grow pearls in the Ohio river; but the people were unfortunately so much addicted to raising corn and pork, that he literally threw pearls before swine, and had the mortification to see them treated with indifference.”

Today, Rafinesque is mostly associated with Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky (which has nothing to do with vampires – the name means “across the woods”). He spent seven contentious years there as an unwelcome professor of natural history and botany. The president of the university preferred classical studies and tried to ban this self-taught scientist, but Rafinesque wrangled an unpaid position through friendship with a wealthy trustee. Since the university refused to pay him, Rafinesque sold tickets to his scientific lectures and also to the classes on ancient and modern languages he taught on the side.

Once, on returning to Transylvania from a leave of absence, Rafinesque discovered that the university had leased his room to a several students and dumped his books and specimens in storage. He resigned in a huff, allegedly cursing the university and its president and moved to Philadelphia. Within a couple of years, the president was dead and the university suffered a major fire, so the legend of “Rafinesque’s Curse” spread.

On his way east, Rafinesque rebranded himself as a “pulmist” or specialist in lung disorders and sold a patent medicine concoction called “Pulmel” through advertisements in Cincinnati newspapers.

While in Philadelphia, Rafinesque published his most unusual project, a volume so strange it has had scholars scratching their heads for almost two centuries. The “Walam Olum” or “Red Record” purports to be a historical record of the Lenape (Delaware) Tribe of Native Americans. Rafinesque claimed to have received this document in the form of birch-bark sheets from a “Doctor Ward” who practiced in Dearborn County, Indiana. The doctor – who has never been conclusively identified – said he received the sheets from a Lenape tribe member grateful for an efficacious medical treatment. Rafinesque claimed the original birch-bark sheets got lost, so the only source for this unique cultural artifact is his own manuscript. Recent scholarship has proven almost definitively that the “Walam Olum” is a hoax perpetrated by Rafinesque to support his eccentric theories about the origins of Native Americans and, possibly, to qualify for a munificent French stipend.

Rafinesque died in Philadelphia, and this is where his story gets really weird. According to legend, the impoverished naturalist was buried in a pauper’s grave. The legend is simply not true. Rafinesque was hardly impoverished. Just before he died he published several books at his own expense and he was renting a house to contain his collections. The “pauper’s grave” was actually a charitable cemetery established as an alternative to the Potter’s Field for “strangers.” Strangers meant people who were denied burial in a churchyard because they lacked church membership.

In 1924, having had a century to get over Rafinesque’s curse and seeking to polish its reputation by association with the increasingly famous scientist, Transylvania University had Rafinesque’s bones exhumed and reburied beneath the administration building. Every Halloween, a select handful of Transylvania students spend the night in Rafinesque’s tomb.

Problem is, those aren’t Rafinesque’s bones. The cemetery in which he was buried and from which he was exhumed buried at least five other corpses in the same plot along with Rafinesque and it is almost certain that the bones of one Mary Passimore now lie beneath the steps of Old Morrison Hall on Transylvania’s campus.

Still, even in death, Rafinesque inspires a great party. Charles Boewe, who spent half a century unraveling Rafinesque’s biographical and thanatological mysteries, enjoyed his student-led tour of Transylvania.

“The guide may tell you that Rafinesque Day, occurring about Halloween time, has become a tradition at Transylvania, and that on that night four lucky students, two boys and two girls, are selected to pass the night together in the crypt, ‘right here on these graves!’ The guide is less likely to tell you that part of the Rafinesque Day festivities consists of a bonfire that night, and that boys dressed as undertakers solemnly carry a black coffin around the fire, while, in some years, students have been known to scream obscenities to release whatever primordial urges bedevil students in the autumn when the moon is full.”

That old cemetery in Philadelphia was graded and transformed into a playground in 1950. Depending on how deep the bulldozers scraped, Rafinesque’s actual bones were either dumped 18 miles away on the grounds of another cemetery, or lie beneath a (hopefully not cursed) baseball diamond.

Meanwhile, specimens of the lovely little fossil shell, Rafinesquina, are found in museums throughout the world.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

as if, if. Pinks. dili rain.

obliguo imping es as if if et noe o not till enhet I 1 , as if If we make this Observation; they design’d to give some disturbance to 2 the Grass be Rotted, tangled or clung together. Also a Term or Gravelled, and to look after Sheep apply’d to Herbs, when they grow as if if the Weather prove Rainy, lest the they were Plaited together; as Matted Rot surprize them. Pinks. 3 I was informed [ that this play having been once acted, this personage when he came upon the stage ] appeared double, as if if the real 4 may dili rain de novo; as if If distress die 5 — supernatu umph, which [ ] as if if they knew the Hawkesburies 6 as if if therefore 7 was much the same as if If he were totally unacquainted with 8 the blood of the first purchaser; as if If a man hath issue 9 as much as if if 10 — reduction of their issues, as may be made without producing public inconvenience. — as: “if - If 11 of as if ( if within twenty days ) to these 12 his own interest: as if, if it was entered into 13 added to the discompo dicated as much as if if you will sure of 14 the same as deeply as if if I contract with 15 — nach as, as soon as, as if, if, however, till, untill, though, unless, when, while, ftatt des Verbi finiti gebraucht, 16 as if if any person within any 17 for ever, as if this were their rest and portion, and as if If any of our fallen race desire 18 “as if” if it shall be considered expedient 19

now without them; as if if they can that did it, for I neither can nor will. 20 — clearness and transparency (as if If it be bloody, there is probably a degree filtered) 21 And yet, [ ] after a pause, “I feel as if — if I were a while [ ], and leaves rustling over 22 numb and as if ! if the heart was constricted. bound 23

as if if had gone to sleep. Illic-an. 24 As if were if break-ing As if if break-ing hearts [ ] As if if 25 — the collocation of the words, the expression summarily, be the same in all respects as if “if any” refers to 26 duties as if if 27 As if if it was As if if it was for anything but 28 as if “if” was the word?—Yes. [ ] If they treat it as meaning “if,” [ ], which is nonsense. 29 I feel as if if I hadn’t 30

sources (through 1923); some (two) from 1923-39

1 OCR confusions at scan of mss, Logica maior Aristotelico-Thomistica (BSB Clm 27849 b; 1694) : 1178 Bavarian State Library copy, digitized July 17, 2014 2 OCR cross-column jump, ex The British Apollo, or, Curious amusements for the ingenious. To which are added the most material occurences foreign and domestick. (London, December 1st. to 3rd., 1708) : 46 wonderful index to this volume, which is discussed (with other advice columns and their forebears, Daniel Defoe’s Little Review among them) at wikipedia 3 OCR cross-column misread (entries for “Matted” and “May”) in Dictonarium Rusticum, Urbanicum & Botanicum. Or, a Dictionary of Husbandry, Gardening, Trade, Commerce, and all Sorts of Country-Affairs. Volume II. Illustrated with a great Number of Cutts. (Third edition, revised... London, 1726) : 65 by John Worlidge (1640-1700 *) and Nathan Bailey (d1742 *) 4 OCR misread (showthrough noise), ex Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “An Epistle to Mr. D’Alembert,” in The Works of J. J. Rousseau (Vol. 3, of five, London 1767) : 174 5 OCR cross-column misread (for “distrain”), &.c., at Thomas Leach. Modern Reports, Or, Select Cases Adjudged in the Courts of King’s Bench, Chancery, Common Pleas, and Exchquer, Volume the twelfth. Third edition, corrected. (London, 1796) : 646 6 OCR cross-column misread, at Cobbett’s Annual Register (December 18, 1802) : 795-96 7 OCR cross-column jump, at “Trial of Thomas Whitebread, and others, for High Treason” (1679) in Cobbett’s Complete Collection of State Trials... Vol. 7 (1810) : 319-20 8 ex “Debate in the Commons on Mr. Fox’s Motion for Leave to bring in his East India Bills. A. D. 1783,” in The Parliamentary History of England... vol 23 (tenth of May 1782, to the first of December 1783); (Hansard, London, 1814) : 1187-1213 (1195-96) aside — the State assuming debt of (and responsibilities of/for) the East India Company, and entanglements in / entrapment of the subcontinent... 9 OCR cross-column misread, at Thomas Walter Williams. A Compendious and Comprehensive Law Dictionary; elucidating the terms, and general principles of law and equity (London, 1816) : at Discent [sic] 10 ibid. (1816), similar misread at Bill of Exchange 11 OCR misread, show-through confusion, at “Second report on the expediency of the bank resuming cash payments” in The Pamphleteer 14 (London, 1819) : 24 12 Letter from L.S. re: Dr. Tomlinson’s Library, &c., in The Newcastle Magazine 4:1 (March 1821) : 393-396 (394) 13 ex Chapter 14, “Of a Lease,” in William Sheppard, The Touchstone of Common Assurances being a plain and familiar Treatise on Conveyancing. With copious notes, and a table of cases cited therein; to which is added, an appendix, and an extensive analytical index (by Edmond Gibson Atherley). 8th edn, Vol. 1 (London, 1826) : 270 14 ex “The Delights of a London Omnibus.” in The Bath and West of England Magazine (For March, 1836) : 88-90 15 OCR cross-column misread, at “Maxims of the Law. Law Tracts,” in The Works of Lord Bacon, with an introductory essay, and a portrait. Vol. 1 (of 2; London, 1837) : 544-570 (556) 16 ex notes to “My Fellow Clerk. A farce in one act,” by John Oxenford, in K.F.A.P. Thornhill, Englisches lesebuch, oder, Antleitung um auf die leichtfasslichste Weise das Englische schreiben und sprechen zu lernen... (Stuttgart, 1839) : 17 (similar at p44) 17 OCR cross-column misread, at definition of “Embezzlement,” in John Bouvier, A Law Dictionary, Adapted to the Constitution and Laws of the United States of America, and of the several states of the Amerian union; with references to the civil and other systems of foreign law. Vol. 2 (of 2; Philadelphia, 1839) : 358 on John Bouvier (1787-1851), consult wikipedia; in addition to being jurist and legal lexicographer, he was father of Hannah Mary Bouvier Peterson (1811-70 *), author of books on science, astronomy and cookery. 18 OCR cross-column misread, notes to James, chapter v, in Thomas Scott (1747-1821 *), The Holy Bible, containing the Old and New Testaments... with explanatory notes, practical observations, and copious marginal references. Vol. 6 (London, 1839) : 415 19 OCR cross-column jump, at “To the People of the State of North Carolina” (concerning handling and treatment of Black “servants”) in Volume of Speeches Delivered in Congress, 1840, Including Discussions of the Independent Treasury Bill, the Extension of the Cumberland Road, the Bankruptcy Bill, and Other Matters of National Finances (Stanford copy; 1840) : 6 20 OCR cross-column misread/jump, at Richard Baxter, “Gildas Salvianus. The Reformed Pastor; showing the nature of the pastoral work; especially in private instruction and catechizing: with an open confession of our too open sins. Prepared for a day of humilation kept at Worcester, December 4, 1655...” in The Practical Works of Richard Baxter : With a Preface, giving some account of the author, and of this edition of his practical works; and essay on his genius, works, and times; and a portrait. Vol. 4 (of 4; London, 1854) 353-484 (410) on Richard Baxter (1615-91) consult wikipedia 21 snippet view, evidently OCR cross-column misread at The Homoeopathic Echo : A Journal of Health and Disease (1855) : 200 22 snippet view, evidently OCR cross-column misread at Cassell’s Family Magazine (1875) : 163 the whole — And yet , “ Oh ! no , ” she answered , gravely , and for a little she continued after a pause , “ I feel as if — if I were a while both Amy and Winifred sat in silence , with the man I should choose some particular occupation , and leaves rustling over ... 23 OCR cross-column misread, at Lectures on Diseases of the Heart : With a Materia Medica of the New Heart Remedies. By Edwin M(oses). Hale., with A Repertory of Heart Symptoms by E. R. Snader. Third edition, greatly enlarged. (Philadelphia, 1889) : 338 something on Hale (1829-99) at sueyounghistories 24 OCR misread of “if” for “it,” ex entry “The Face. Sen / Sensation,” in William D(aniel). Gentry (1836-1922?), his The Concordance Repertory of the More Characteristic Symptoms of the Materia Medica. Vol. 1 (New York, 1890) : 800 25 OCR confusion over musical score, “The Swan and the Skylark, Cantata.” The words by Hemans, Keats, and Shelley; the music composed by Arthur Goring Thomas (posthumous work) (London and New York, 1894) : 49 score at IMSLP (International Music Score Library Project) on Arthur Goring Thomas (1850-92), see wikipedia 26 OCR cross-column misread, ex Justice of the Peace (London; April 23, 1898) : 272 27 OCR cross-column jump, ex “In re John Scott, Jun. (Deceased).” January 27, 1900. The Weekly Reporter 48 (1900) : 208 28 ex Horace Traubel, “I’m just talking all the time about love,” in The Conservator 21:5 (Philadelphia, July 1910) : 68-70 (69) some OCR cross-column confusion, involving these lines — As if if it was for anything but just love the whole and be deceived : business would not go to pieces : And so I am gagged and bound and put into As if if it was for anything but just love it could prison ... all tagged Horace Traubel (1858-1919) see also wikipedia 29 regarding “Clause 87” ? ex preview snippet (only), Sessional Papers (House of Lords), Volume 6 (1926) : 44 30 ex Fiction Parade and Golden Book Magazine (1936) full snippet preview — he stopped , of cool has come instead . It ’ s a sort of then went on haltingly , you said you calm feeling I have , like floating wouldn ’ t have thought badly of me through heaven on a cloud . I feel as if if I hadn ’ t . . . ” I were dead , as if everything ...

—

an aside (about method and motives) — as if, if it’s not been said before, an aside or error in some out-of-the-way obscurity, snatch of glanced breeze, there’s nothing, and so nothing to report.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

From their balloons, the first aeronauts transformed our view of the world

by Jennifer Tucker

A lithograph from Gaston Tissandier’s balloon travels depicts falling stars. Archive.org

Near the beginning of the new film “The Aeronauts,” a giant gas-filled balloon called the “Mammoth” departs from London’s Vauxhall Gardens and ascends into the clouds, revealing a bird’s eye view of London.

To some moviegoers, these breathtaking views might seem like nothing special: Modern air travel has made many of us take for granted what we can see from the sky. But during the 19th century, the vast “ocean of air” above our heads was a mystery.

These first balloon trips changed all that.

Directed by Tom Harper, the movie is inspired by the true story of Victorian scientist James Glaisher and the aeronaut Henry Coxwell. (In the film, Coxwell is replaced by a fictional aeronaut named Amelia Wren.)

In 1862, Glaisher and Coxwell ascended to 37,000 feet in a balloon – 8,000 feet higher than the summit of Mount Everest, and, at the time, the highest point in the atmosphere humans had ever reached.

As a historian of science and visual communication, I’ve studied the balloon trips of Glaisher, Coxwell and others. Their voyages inspired art and philosophy, introduced new ways of seeing the world and transformed our understanding of the air we breathe.

The first balloon flights

Before the invention of the balloon, the atmosphere was like a blank slate on which fantasies and fears were projected. Philosophers speculated that the skies went on forever, while there were medieval tales of birds that were so large they could whisk human passengers into the clouds.

A drawing from ‘Astra Castra’ depicts mythic birds that can transport people up into the skies. Archive.org

The atmosphere was also thought of as a “factory of death” – a place where disease-causing vapors lingered. People also feared that if they were to ascend into the clouds, they’d die from oxygen deprivation.

The dream of traveling skyward became a reality in 1783, when two French brothers, Joseph-Michel Montgolfier and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier, launched the first piloted hot-air balloon.

Early balloon flights were difficult to pull off and dangerous. Aeronauts and passengers fell to their deaths when balloons unexpectedly deflated, caught fire or drifted out to sea. Partly due to this inherent danger, untethered balloon flight became forms of public entertainment, titillating crowds who wanted to see if something would go wrong. The novelist Charles Dickens, horrified by balloon ascents, wrote that these “dangerous exhibitions” were no different from public hangings.

Over time, aeronauts became more skilled, the technology improved and trips became safe enough to bring along passengers – provided they could afford the trip. At the time of Glaisher’s ascents, it cost about 600 pounds – roughly US$90,000 today – to construct a balloon. Scientists who wanted to make a solo ascent needed to shell out about 50 pounds to hire an aeronaut, balloon and enough gas for a single trip.

The view of angels

Some of the first Europeans who ascended for amusement returned with tales of new sights and sensations, composed poems about what they had seen and circulated sketches.

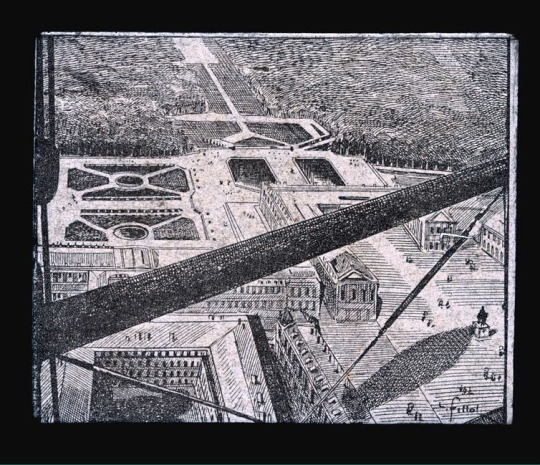

A glass lantern slide of a print titled ‘The View of Versailles.’ Private collection, used with permission.

Common themes emerged: the sensation of being in a dream, a feeling of tranquility and a sense of solitude and isolation.

“We were lost in an opaque ocean of ivory and alabaster,” the balloon travelers Wilfrid de Fonvielle and Gaston Tissandier recalled in 1868 upon returning from one of their voyages.

In an 1838 book, one of the most prolific writers on the topic, professional flutist Monck Mason, described ascending into the atmosphere as “distinct in all its bearings from every other process with which we are acquainted.” Once aloft, the traveler is forced to consider the “world without him.”

A drawing of dreamlike clouds from the travels of Wilfrid de Fonvielle and Gaston Tissandier. 'Travels in the Air'

French astronomer Camille Flammarion wrote that the atmosphere was “an ethereal sea reaching over the whole world; its waves wash the mountains and the valleys, and we live beneath it and are penetrated by it.”

Travelers were also awestruck by the diffusion of light, the intensity of colors and the effects of atmospheric illumination.

One scientific observer in 1873 described the atmosphere as a “splendid world of colors which brightens the surface of our planet,” noting the “lovely azure tint” and “changing harmonies” of hues that “lighten up the world.”

And then there were the birds-eye views of the cities, farms and towns below. In 1852, the social reformer Henry Mayhew recalled his views of London from the perch of “an angel:” “tiny people, looking like so many black pins on a cushion,” swarmed through “the strange, incongruous clump of palaces and workhouses.”

To Mayhew, the sights of farmlands were “the most exquisite delight I ever experienced.” The houses looked “like the tiny wooden things out of a child’s box of toys, and the streets like ruts.”

So deep was the dusk in the distance that it “was difficult to tell where the earth ended and the sky began.”

A thunderstorm above Fontainebleau, France, from Camille Flammarion’s travels. 'Travels in the Air.'

A laboratory for discovery

The atmosphere was not just a vantage point for picturesque views. It was also a laboratory for discovery, and balloons were a boon to scientists.

At the time, different theories prevailed over how and why rain formed. Scientists debated the role of trade winds and the chemical composition of the atmosphere. People wondered what caused lightning and what would happen to the human body as it ascended higher.

To scientists like Flammarion, the study of the atmosphere was the era’s key scientific challenge. The hope was that the balloon would give scientists some answers – or, at the very least, provide more clues.

James Glaisher, a British astronomer and meteorologist, was already an established scientist by the time he made his famous balloon ascents. During his trips, he brought along delicate instruments to measure the temperature, barometric pressure and chemical composition of the air. He even recorded his own pulse at various altitudes.

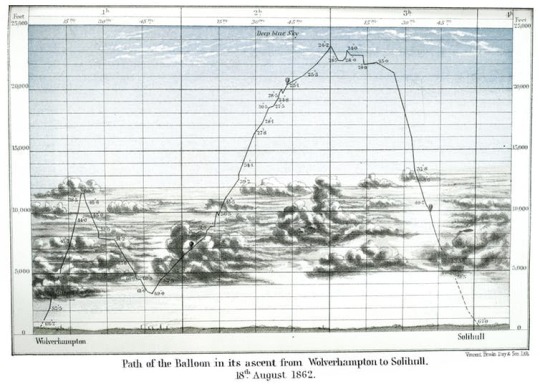

In 1871 he published “Travels in the Air,” a collection of reports from his experiments. He didn’t want to simply write about his findings for other scientists; he wanted the public to learn about his trips. So he fashioned his book to make the reports appealing to middle-class readers by including detailed drawings and maps, colorful accounts of his adventures and vivid descriptions of his precise observations.

Glaisher’s books also featured innovative visual portrayals of meteorological data; the lithographs depicted temperatures and barometric pressure levels at different elevations, superimposed over picturesque views.

James Glaisher charted his balloon’s path from Wolverhampton to Solihull, England. 'Travels in the Air.'

He gave a series of popular lectures, during which he relayed findings from his trips to riveted audiences. Two years later, he published an English translation of Flammarion’s account of his balloon travels.

The trips of Glaisher and others gave scientists new insights into meteors; the relationship between altitude and temperature; the formation of rain, hail and snow; and the forces behind thunder.

And for members of the public, the atmosphere was transformed from an airy concept into a physical reality.

youtube

The trailer for ‘The Aeronauts.’

About The Author:

Jennifer Tucker is an Associate Professor of History and Science in Society at Wesleyan University

This article is republished from our content partners over at The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

#science#meteorology#atmospheric science#hot air balloon#citizen science#movies#Science Fiction and Fantasy

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Surprise Victory for Robert Mylne

On September 23rd, 1758, an aspiring architect named Robert Mylne (1733 – 1811) wrote to his younger brother William (1734 – 1790) with astonishing news. At twenty-four years old, Robert had just become the first Briton awarded top prize in the Concorso Clementino, a famous architecture competition held every three years in Rome.[1] This drawing of an altar—completed during a timed exam—was submitted as part of his winning entry.

Portrait of Robert Mylne, 1783; engraved by Vincenzo Vangelisti after a drawing by Richard Brompton (1757); National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG D5326

Robert and William Mylne were Scottish, born in Edinburgh to a family of builders: their ancestors were stonemasons.[2] After preliminary training in their native city, the brothers continued their architectural education in Europe. They traveled first to France, then made their way (mostly by foot, on account of the cost) to Rome, where they arrived in 1755.[3] In the Eternal City, Robert and William studied antiquities, attended lectures at the Accademia di San Luca (Academy of St. Luke), and built relationships with prominent architects such as Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720 – 1778).[4] Unable to disguise their modest origins, in Rome the Mylne brothers earned the scorn of Robert Adam (1728 – 1792), a Scottish architect of much greater means. Adam described them as having “neither education nor money,” though he noted begrudgingly that Robert “begins to draw extremely well.” [5] In 1757, William returned to Edinburgh. Robert however remained in Rome, determined to try his hand at the Concorso Clementino.

The contest, named in honor of Pope Clement XI, had been established by the Academy in 1702.[6] It carried enormous prestige, and was specifically intended for architects early in their careers. The competition consisted of two separate trials. First, several months before each Concorso, the Academy would announce the subject for the upcoming contest. In Robert Mylne’s year, the contestants were tasked with producing a series of drawings for “A Public Building with a Memorial Gallery to exhibit Busts of Eminent Men.”[7] When the deadline arrived, competitors submitted plans, sections, elevations, and whatever other drawings they felt would convince the judges of the superiority of their projects.

Robert Mylne, Interior and Exterior Longitudinal Sections, Concorso Clementino, 1758; Rome, Accademia Nazionale di San Luca. (The yellow color of this drawing is the result of extended exposure to light during display.)

In the second phase of the contest, the architects gathered for an extemporaneous feat of drawing, the subject kept secret until the event. Mylne sat for this test, called a prova, on the 7th of September, 1758.[8] Afterwards, he recalled the experience in the letter to his brother: sitting before a panel of judges, the competitors were given two hours to design a “magnificent” altar adorned with composite columns.[9] “I am sure you are quaking for me now,” Mylne wrote, “however I made it out and a fine one—in comparison with the rest.”[10] What he produced was this relatively simple sheet in the Cooper Hewitt collection, bearing the elevation and plan of an altar in a modern, French-inflected Neoclassical style. At the top, the architect has added and identified allegorical figures of Hope, Humility, and Faith. A few days after the prova, Mylne learned he had been unanimously selected for the first prize. The announcement shocked him. “I think on my heart when I received the news—thump, thump, thump, I feel it yet…”[11]

His triumph in the Concorso Clementino launched Mylne’s career. In Rome he was honored with a fabulous ceremony attended by Cardinals, and presented with a silver medal. His winning drawings were displayed in the Academy building and earned much praise (although not from Robert Adam and his supporters, who—full of sour grapes—continued to sneer). [12] Mylne returned to Britain the following year, where his Italian victory was soon overshadowed by another major success. In 1760 he submitted drawings for a competition to design the new bridge over the Thames at Blackfriars. And won. [13]

A View of Part of the Intended Bridge at Blackfriars, London, ca. 1764; etched by Giovanni Battista Piranesi; Metropolitan Museum of Art, 62.600.683

Dr. Julia Siemon is Assistant Curator of Drawings, Prints & Graphic Design at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

[1] Damie Stillman, “British Architects and Italian Architectural Competitions, 1758 – 1780,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol.32, No. 1 (Mar., 1973): 44 – 66, 44 – 45

[2] A. E. Richardson, Robert Mylne: Architect and Engineer, 1733 to 1811 (London: B.T. Batsford, 1955), 15

[3] William first went to France on his own, where he studied for a period before being joined by Robert so that the brothers could travel together to Italy. Stana Nendacic, “Architect-Builders in London and Edinburgh, c. 1750 – 1800, and the Market for Expertise,” The Historical Journal, Vol. 55, No. 3 (September 2012): 596 – 617, 599

[4] Richardson, 14

[5] Lindsay Stainton, “Hayward’s List: British Visitors to Rome, 1753 – 1775,” The Volume of the Walpole Society, Vol. 49 (1983): 3 – 36, 28; Nenacic, 611

[6] Stillman, 44

[7] Stainton, 28. The rules of the competition listed several specific requirements, including architectural elements such as an atrium, a theater, etc., as well as clarifications regarding the submission of a “plan, prospect, and section, and anything else that might be required to give a good demonstration of the idea.” These were printed in a celebratory publication for the awards ceremony, Delle lodi delle bele arti… del concorso celebrate dall’insigne Accademia del Disigno di S. Luca… l’anno MDCCLVII (Rome, 1758).

[8] Stillman, ibid. The Cooper Hewitt collection also includes a prova carried out by another British architect, Joseph Gandy, who won the Concorso Clementino in 1795.

[9] “Magnifico Altare con colonne d’Ordine composito per farsi in una della principali Capelle con suoi ornati.” See Stillman, 45

[10] Robert Mylne to William Mylne, 23 September, 1758, in Stillman, 44.

[11] Mylne in Stillman, ibid.

[12] Stillman, 41 n. 21.; 44

[13] For the bridge, see Roger Woodley, “‘A Very Mortifying Situation’: Robert Mylne’s Struggled to Get Paid for Blackfriars Bridge,” Architectural History, Vol. 43 (2000): 172 – 186

from Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum https://ift.tt/3gIycw3 via IFTTT

1 note

·

View note

Text

Saint-Just Ch. 3 part 1 by Bernard Vinot

The translation is based on both French and German version.

Everywhere that I’m unsure about would be notified in the end. Welcome to point out any mistakes that I may make!

3. In Soissons, with Oratorians

No matter from inside or outside, they belong to us, by the mind, the taste, the principles that they have received from us.

Father Batterel

=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=

The death of Louis-Jean de Saint-Just left his widow the responsibility of taking care of the three children. The oldest one of them was only 10-year-old. For several years Louis-Anotine shared his life and education with the children of Blérancourt, until very likely 1779, when his mother decided to send him to College.

In 1675, Saint-Nicolas College was entrusted to the Congregation of Oratoriens, whose educational work didn’t possess the same high reputation as the Society of Jesus (Jésuites). However, it still earned respect by its longing of religious inwardness, from which Oratoire wished “to be blessed by Son of God”. They were also considered to be more interested in contemporary problems, more open to innovation than their rivals, tending to provide modern classes about natural sciences and history. However, given each of their institutions was independent, this judgement didn’t apply to all of them. In particular, the success of Oratoire was due to the expulsion of the Jésuites in 1764, which was evoked by their (Oratoire) close cohesion, influence, and the independence of their political power. Oratoire then frequently took the places of their rivals. At the beginning of the Revolution, the Congregation had 750 members, and possessed 70 houses.

Since the beginning of the 18th century, a complete educational circle had been available in the College of Soissons. The eight lecturers of it guaranteed the education of the students from the 6ème till the years of philosophy*. But the material subsistence of the institution had long been unsecured. It was based only on one benefice, which was granted by the Saint-Gervais Cathedral of Soissons. Also there were moderate incomes from some real estates. In order to make sure the financial stability of such a small College - it consisted of about 150 students - for sure the College would be willing to receive also the students from outside the city. The wealthy family could help wipe out part of the deficit. Yet Oratoire (like the Jésuites before) refused to run boarding schools. Was this probably the reason why Soissons left a negative impression to the Oratorian François Daunou (who taught there)? Anyhow, in the <Education plan submitted to the National Assembly on behalf of the public teaching Oratoire> 1790, he suggested that no student “who’s younger than 9 or older than 12” should come to a boarding school. “If all of those who were put into those sinister institutions got ready to tell us truthfully the moral aberrations of which they had been witnesses, creators, or victims, undoubtedly, there would be fewer parents seeking to get rid of their duties of care”. In Soissons, people rejected the admission of 13-year-old children, because they “are always with a significant absentmindedness and doubtful behaviors”. In 1780, there were 24 boarders, and in 1782, this number was 26. The management group regretted that two guards and two servants had to be provided for such a small group. At least, it makes sense to assume that the students who were such “over-cared”** lived under satisfactory material conditions.

From the boarding regulations, we could tell that the boarders of Soissons should not have an unhappy mood, even if they had to spend a vast amount of their daily time, from 6 am to 9 pm, to study and pray. They were surrounded by attention. In the morning, between 7:30 am and 8 am, a lady would help them comb hair, and a servant help tie their braids. They would curl and powder hair by themselves. After finishing the evening class, before returning back to the dormitory, they would have 15 minutes to insert curlers in their hair, while on holidays a wig maker would wig them. Everyday there would be a tailor to mend the damaged garment, and a laundress would drop by twice a week. Saint-Just would later maintain all the habits, and never neglect his personal hygiene and dressing. The numerous cravats, the suits of exquisite taste, the powder-box - all mentioned in the list of his personal belongings and gave rise to so many controversies - were the things that he had learnt how to use from the College.

The boarding regulations emphasized the equipment and relaxation of the boarders. Every evening they are allowed to browse into the library. In the summer, they would spend every Thursday in the countryside, a hamlet of Vignoles, which belongs to the parish of Courmelles, and is about 6 - 7 kilometers away from the College. The College possessed a property there. On holidays and rest days, they would go out for a walk, and play some intelligent games, like chess, checkers, tric-trac, billard, etc. The food seemed to be very sufficient. The inspecting report*** of 1783 mentioned that 42 people (boarders and staff) had a daily consumption of 62 pounds of bread, and on Mardi Gras, they consumed 38 pounds of meat.

Saint-Just’s family lived 25 kilometers from Soissons. Was he registered as a boarder, or lived in the city privately? No one can tell. In any case, he would be impressed by the beautiful and spacious buildings of the College, probably at the Saint-Luke’s day (18th Oct) of 1779, when he first passed through the portal, on which decorated the bas-relief of Pallas Athene and Ceres, the goddess of wisdom and of agriculture. Above them was the crown of thorns, together with the religious symbol of Oratoire.

Notes:

* It seems that 6ème is the lowest grade of middle school, and years of philosophy means the last two years of study in the collège (I made this conclusion based on the context of next section).

** surencadrés, in German version, überversorgt. I think it should mean that the students were given too much cares. But I’m not 100% sure.

*** inspecting report: These reports (acts de visite) were written regularly by an inspecting Father, A kind of supervisor of Congregation of Oratoriens.

=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=