#LAST GOODBYE the lost Jeff Buckley interview

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Hi! Found this answer on a Redit thread. Your take?

he was probably bi. My friend who i worked with at a record store went out to dinner with him and some band mates and Jeff had some drinks and came on to him. I also knew of a couple of his girlfriends in NYC. He was probably like many people open to many things. That's all I will say.

Then there's this long spiel:

I’m late to the party but I went down a hole with this last year after I too listened to ‘Dream of you and I’ and was like that felt very personal and astute for someone everyone seems to assume is het. I went looking here then too and couldn’t find anything so hopefully the next person like me will find this.

I’m a queer person and have always strongly identified and loved his music but besides just my personal opinion that many of his songs have that ~queer energy~ and coding in them I did find a couple of less subjective things. Unfortunately none which lead to solid answers but might make other queer people like me feel happy and satisfied with what we are seeing in him (people who are die hard 'he could never be gay blah blah he’s had all these gfs' are never going to come around but for the rest of us it might be enough).

First big one is this 1997 article published a month after his death. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1997-06-20-9706200305-story,amp.html it quotes him twice describing himself as a homosexual and gay. Unfortunately I can’t find the original articles from which the quotes are pulled for more context but for the most part... idk if we really need it. Feels to me like the author saw how he was being memorialised (perhaps knew him personally idk) and didn’t want this part of him to get lost. Here are the quotes in the event that article disappears one day too...

It's all about getting to a place where I can let my deepest eccentricities out," Buckley once said in an interview shortly after the Uncommon Ground show. "I just see things a little differently and express myself a little differently and I think it's because I haven't been in one place for very long (in four years, Buckley attended three high schools). So I was seen from my childhood as hyperactive, homosexual, weird, insane, obnoxious, offensive, funny. . . . It's a tremendous point of pain, my inability to relate to the status quo."

"I am a storyteller, lounge singer, I am the entertainer, I am the rock star, I am gay, I am wrong, I am there for the story to go down, the cocktail host-shaman, the little romantic chanteuse wanna-be," Buckley once said, trying to explain the image. He says he wanted it as the cover art for the album, but was talked out of it by friends and the record company. "All the men hated my Judy Garland jacket."

The article also mentions Judy Garland's jacket which he wears on the cover of Grace. Which would be my second obvious clue that he’s not a straight man. Idk how much you know about Judy but she was very much an icon in gay male circles at the time and prior - you can look that up if you’re unfamiliar and find plenty of info. He’s spoken about the jacket and other people have spoken about elsewhere too, you could look for more of that if you’re curious.

More directly from Jeff and related to his music is the Last Goodbye video which includes a clip of two men kissing. Pretty self explanatory. Whole video is pretty homo romantic tbh. Can’t imagine the record label was stoked about that if they didn’t even like the jacket. I imagine he would have had to fight to put that in which... why would you do that if you were straight?

Next I found some random forum thread (https://www.datalounge.com/thread/16719162-jeff-buckley) plenty of trolls and people being like no he’s straight and offering no real commentary but also some people who agreed. One gay guy who met him had assumed he was gay and didn’t find out he had a gf till after his death.

“Who actually knows? I met Jeff a bunch of times in NYC in 92/93. He was a nice guy. My BF went to NYU for grad school and I moved back there after leaving in 1988 when I graduated from there. Being back in the city, I threw myself back in the music scene. I would see him play and see him at other venues. I was 2 years older and liked Jazz. We mainly talked about music and guitars. I never asked, but always assumed he was gay. I was shocked when I found out that Joan Wasser was his girlfriend at the time of his death.”

Someone else there also mentions Judy Garland again and his cover of ‘The Man That Got Away’, you can listen to Jeff sing it on the Mystery White Boy live album. You could take his little intro to that song in a queer way too if you wanted.

Someone else in the thread also links to this 1995 MTV interview + outtakes video and just says “he seems gay in this video” which made me laugh but I mean.. they’re not really wrong. You should watch it either way because it’s a cute interview. https://youtu.be/vcxGwQKW6Ac

From the ‘In His Own Words’ book which fortunately and unfortunately is very obviously curated there are a couple things that are specifically queer. You’ll have to excuse any small errors in this, some of it is hard to read.

“Thanks for the beat, for the sumptuous rhythm you give that I continue at the silent handoff, watch me run baby. My baby’s got a strong right arm. The drag queen... such a queen, queen 4 my lust and juicy hope of happiness somewhere in this world... her back, her shoulders, her ecstatic downcast eyes that lead to her legs... just like my baby oh you should see her, you are both oh such the real thing, such the real thing... I smiled when you weren’t ready (word I can’t make out) the show and I brought you some (cut off page) kissed my cheek and it kept me (cut off page)”

“It’s something you don’t realize You’re funny that way Hatred and fascination Hatred and fascination

For the cultures closest to the earth For the lovers throughout history of the same sex For the feminine in all things For the body itself For the surrender and courage of the heart

DECODE THAT FUCKING EVANGELIST DEVIL DOCTRINE”

I feel like there was one more but I didn’t write it down and I can’t see it just flicking through the book again sorry - if I remember I’ll come back and add it next time I read it. There are other things in the book that also made me think he was queer but they were more subtle. Those are the two things that explicitly mention queerness. There’s also plenty in the book where he writes about sexual attraction to women or alludes to relationships with women so before someone comes at me about not acknowledging that - here I am. I will say though people who are gay have relationships with people of the opposite sex when they’re working themselves out, doesn’t make them any less gay. Also he could be any other variation of queer and be having relationships with people of any and all genders and identities.

You can read into all his lyrics or things he’s said in interviews or his general demeanour or whatever it is you want to. I could keep linking to what I recognise as queer coded but some of it’s more subjective and the rest of it is just too nuanced to try to articulate or argue on the internet.

Sentiment is basically that it’s very likely that he was gay or queer but that it was the 90s and that he grew up in the 70/80s - a time when being gay and out was not something one could comfortably or safely do much of the time. Especially not as a public figure. He was also very young, which unfortunately means maybe he never got to fully realise or authentically live out his queerness. Which really adds another layer of tragedy to his death if I’m honest.

If he was alive today with the evolution of queer language and general understanding we have now who’s to say how someone like Jeff - who was so obviously and openly in touch with his feminine side - would describe his gender identity let alone his sexuality.

Each to their own but if you’re queer and see yourself and your community reflected in him I don’t think anyone can accurately or definitively tell you otherwise.

It's all subjective opinion and an unsubstantiated claim imo...I don't think he was, but, as also claimed, "people that want to insist' won't be convinced otherwise...The Last Goodbye video...they seem to forget, or don't know, the part that involved Merri was inspired by Jean Cocteu who was, if the blurb I read is correct, gay... perhaps that was included to reflect that? Or maybe something similar was in something related to him that inspired? Who knows? They were also friends of her's, maybe she wanted them to be in it for whatever reason. They also miss a crucial thing: Jeff, to me anyway, did not think along lines, and may have acted in ways perceived as gay (hence being called so as a kid), but didn't think of it as being "gay" or "not gay", he just did whatever came, it doesn't necessarily mean he's gay...also, what they take as "codes" may not actually be (and people, please don't @ me, this is only my opinion and impression... I was asked, I'm replying, thanks)...

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grace & Jeff Buckley

Jeff Buckley was a singer/songwriter who became famous in the late 1990s with the release of his only studio album, Grace.

After touring extensively, developing a tremendous following, and receiving critical acclaim, Buckley was ready to begin recording material for his sophomore album. The next day, while waiting for his band to arrive in Memphis, he decided to swim fully clothed in Wolf Harbor, a tributary of the Mississippi.

Tragically, he got caught in the wake of a passing tugboat and dragged underwater, and he drowned. His autopsy showed no signs of drugs or alcohol, and his friend, who remained on shore, verified that he had not intended to end his own life.

The title song of the only album he would ever record had these haunting lyrics:

There's the moon asking to stay Long enough for the clouds to fly me away Well it's my time coming, I'm not afraid, afraid to die My fading voice sings of love But she cries to the clicking of time, oh, time Wait in the fire, wait in the fire Wait in the fire, wait in the fire

Reportedly, Buckley wrote this song after saying goodbye to his girlfriend at the airport and feeling the wave of emotions in the moment.

I've loved this song for a long time because, even though the title is "Grace," Buckley never uses the word once in the song. The lyrics, though, reveal something about Buckley's understanding of grace.

There's something about how he phrases this particular stanza, which is the most crucial part of the song, that speaks to a person who regrets things done and left undone. He feels his beloved's love wash over him, realizing he doesn't deserve its depth.

When he sings "Wait in the fire" repeatedly, he also realizes how this grace is refining him, making him new.

In an interview before his death, Buckley was asked why the idea of grace was so important to him and why he named both the song and the album Grace. This is what he said:

Grace is what matters in anything - especially life, especially growth, tragedy, pain, love, death. That's a quality that I admire very greatly. It keeps you from reaching out for the gun too quickly. It keeps you from destroying things too foolishly. It sort of keeps you alive.

The irony of that last line is not lost on me, considering Buckley's untimely and tragic passing right as he realized his dreams.

But when you look closely at the one line from the song where he sings, "Well, it's my time coming. I'm not afraid, afraid to die." Something is haunting and beautiful about it. It was grace, after all, that gave him the feeling of peace that enabled him to no longer fear what lay ahead.

None of us knows what lies around the bend in life's journey. But when we learn to embrace the grace we are given, we can face whatever comes with serenity.

And the grace we are given by God far surpasses any we might receive from others. God's grace covers us completely, but because we don't often stop to think deeply about just how all-encompassing it is, we frequently miss out on the experience of that realization.

The grace of God surrounds us, is within us, and is also something that we ought to let flow through us to a world in need of it.

May we learn to wait in the fire of the grace of God and be refined, renewed, and become the best and truest versions of ourselves because of it.

And may the grace and peace of our Lord Jesus Christ be with us all, now and forever. Amen.

#dailydevotion#dailydevotional#christian living#faith#dailydevo#leon bloder#spiritualgrowth#presbymusings#leonbloder#spirituality#jeff buckley

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jeff Buckley: The Lost Interview

In this previously unpublished conversation from 1994, captured just days before the release of ‘Grace,’ the mythic singer-songwriter pushes through self-doubt, professes his undying love for the Smiths and New York City, and interprets a dream wherein he critiqued a serial killer’s photography.

July 21, 2022 by Tony Gervino

In August of 1994, I interviewed the singer-songwriter Jeff Buckley for over an hour at the New York offices of Columbia Records. Other than pulling a few quotes for a regional music newspaper profile I wrote at the time, this conversation went unused. I put the recording in a box in my closet, where it remained for a quarter-century.

I went back over the transcript a couple of years ago and realized that our conversation offered a rare snapshot of the most pivotal moment in Buckley’s too-brief career. He hadn’t yet sat for many interviews and was trying to figure out his own narrative, just before he was to leave on a national tour that would make such quiet, thoughtful introspection a luxury.

The son of folk visionary Tim Buckley, he had made his mark in New York City as a solo artist in 1993, performing a suite of original songs and genre-spanning covers with only his guitar and multi-octave vocal range. The buzz didn’t really build; it seemed as if one day no one in the city’s music scene knew who Jeff Buckley was, and the next, everyone knew.

Prior to entering the studio to record his landmark debut album, Grace, which featured his most successful single, “Last Goodbye,” as well as his transcendent rendition of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah,” Buckley mothballed his troubadour set. To help bring dimension to the music swimming around in his head, he recruited the collaborative working band of guitarist Michael Tighe, bassist Mick Grondahl and drummer Matt Johnson. He wanted his solo album to sound big, ambitious and genre-slippery as he headed to Bearsville Studios in Woodstock, N.Y.

Even though our meeting was less than two weeks before the album release, Buckley was still tinkering with the mixes on Grace, tormenting producer Andy Wallace with sonic flourishes and rewritten bridges, and hoping to squeeze every bit of inspiration out of himself before the tape stopped rolling. In the pre-streaming world, this was an unheard-of high-wire act for a debut artist. But for a young musician who was signed to Columbia Records after a prolonged bidding war, it indicated a bit of acquiescence on the label’s part. From what they’d seen of him, Buckley was a can’t-miss artist. He just needed time, which, tragically, he was ultimately denied. Jeff Buckley drowned in Memphis in May of 1997, just 30 years old.

I’ve edited this interview for length and clarity and removed some passages where I thought Buckley’s sarcasm could be misinterpreted, or where it spun off into tangents that ended with Buckley impersonating everyone from Paul McCartney to the French poet Baudelaire. He had the nervous energy of someone about to embark on a long journey, uncertain of its destination, and I wanted to ensure his answers would properly reflect not just his wit but his wisdom. ***** How does it feel to have to do interviews?

Well, at the outset I guess I figured why would anybody care? But I’m smart enough to know that people would want to talk about my music. I just didn’t think anyone would for a publication. But at this point the fatigue hasn’t set in, and no question is a stupid one. It’s still early.

[laughs] Mainly it’s helpful because I’m getting some ideas out about exactly what I think about some things. And the important thing in doing interviews is not to have any pat answers. That would make it unenjoyable for me. Like a … a murder suspect or something, in terms of having your story straight. Have you finished mixing the new album? No, I have one last day in the studio — one last gasp of creative breath before I have to go away. I’m totally pissed. Absolutely.

Did you write in the studio, or did you go in with the songs ready?

One of them was completely organized in the studio. But that was still prepared beforehand. A lot of stuff we’d done at the last minute because I was trying to get the right people to play with, and it took a while before I found them.

But that was only three weeks before I’d gone up to Woodstock to record and we hadn’t known each other that long, and the band material hadn’t developed as much. Some things were completely crystallized, and some things needed care, and they got it. I’m still not satisfied.

Let’s see: I get to go into the studio on Wednesday, the day before I leave and the night after I perform at [defunct NYC club] Wetlands. So I have one, two, three, four, five precious days to [work on the music], along with all the other stuff I have to do. I have to shoot some pictures, possibly for the album cover. Then at night I’m free to get these ideas together, and I’ll still have one last shot on two songs in particular. The producer [Andy Wallace] doesn’t even know what I want to do to this one song. [laughs] He’ll be horrified.

Have you played it out?

Uh-huh. There are just things I want to crystallize about it.

Is figuring songs out onstage a conscious effort on your part to fly or fail?

Yeah, because I love flying so much. But, really, it’s still a kind of discipline. I guess it’s an engagement. It’s not like having “song 1 to song 6 and then a talk.” I don’t know anybody who really does that. I know a lot of performers talk about not being so structured. … Sometimes you can see bands that have a set of songs, and that shit is dead. That … shit … is … dead.

When I perform, I’m working off rhythms that are happening all over the place, real or imagined, and it’s interactive. It’s got a lot of detail to it, so I can’t afford to tie it up in a noose, and put it in a costume that doesn’t belong on me. So yeah, it’s free but it has its own logic, and sometimes it completely falls flat on its face. But it’s worth the fall, sometimes. Because that’s life.

To me it makes sense to do things in that manner, because that’s really just the way life is when you step out of it and see that, like, your car has a flat and somebody smashed in your windshield and then, shit, you’re walking home and all of a sudden you run into somebody that turns out to be your favorite person for the rest of your life. It’s always … unfolding. You just have to recognize it, I guess. And that’s my philosophy, that I haven’t really thought about until you asked me.

Have you been a solo performer out of desire or necessity?

Both. I did it to earn money to pay rent in the place I was staying, and bills, and my horrible CD habit, and failing miserably all the time, always playing for tips and always just getting by — by the skin of my teeth.

To get this sound in order, you can have a path laid out in front of you, but if you don’t have the vehicle to go down the road you’ll never get to where you want to go. So I guess I was building the parts piece by piece or going through different forms, reforming them and trying out different ideas and songs.

How long have you been building these parts?

Some of them I wrote when I was 18 or 19, and some of them I wrote weeks ago, and some of them I’m still writing. [laughs] The rest of this album is kind of a purging, because the rest of the albums ain’t gonna happen like this. [points to chest] You’ll never see this person again.

Who and what are you going to become, Jeff?

I don’t know, just something deeper. Nothing alien, just something deeper. I’m just not satisfied. I’m really, horribly unsatisfied. Cause I kind of got an idea of where I want this thing to go. It’s still gonna be songs. I think about deepening the work that I do, and other problems I try to solve, like, “If I go to see this band in a loft, or if I went to see this band in a theater, and I wanted to be very, very, very enchanted and very engaged and maybe even physically engaged to where I’m dancing or where I’m moshing, what would that sound like? If I wanted to be cradled like a baby or smashed around like a fucking Army sergeant, what would that sound like?” I daydream all the time about it. And that’s sort of what I work toward. It’s more of an intimate thing.

In America the rock band is not an intimate thing, but in America soul bands are very intimate and blues bands are very intimate, like way back in the day, when people who invented blues were doing it. It’s all very interdependent and it’s all very … people had to listen to make the music. And it comes around in a lot of different ways. Things I’m doing now are pretty old-fashioned: I’m going on tour to little places to play small cafés. [He lays his itinerary out in front of us.]

What do you expect the reaction to be? You play New York City and, by now, the people here know your deal, but there are some cities where they’re not going to know.

That’s OK.

Will you tailor your performance to different tour stops? Does it change the way you perform?

Every time I perform it’s different.

How long have you been in New York City?

Three years. But I’ll always be here. I’ll always live here.

What is it about New York?

Everything. You know all the clichés: It’s the electricity, it’s the creativity, it’s the motion. It’s the availability of everything at any moment, which creates a complete, innate logic to the place. It’s like, there’s no reason why I shouldn’t have this now. There’s no reason I shouldn’t have the best library in the country, and there’s no reason why the finest Qawwali singer in all of Pakistan shouldn’t come to my neighborhood and I’ll go see him, and there’s no reason that Bob Dylan shouldn’t show up at the Supper Club.

There’s no reason that I can’t do this fucking amazing shit. And if you have a certain amount of self-esteem, it’s the perfect place because there’s so much. It’s majestic and it’s the cesspool of America. And there’s amazing poetry in everything. There are amazing poets everywhere, and some real horrible mediocrity, and an equal amount of pageantry. There’s also a community of people that have been left with nothing but their ability to put on a show, no matter what it is — whether it’s a novel or a performance reading on Monday night at St. Mark’s Church for 20 minutes. Where do you do the bulk of your writing?

Everywhere. You know what? Mostly it’s in 24-hour diners, on too much coffee. That’s an old Los Angeles thing.

How much does the location affect the writing?

To me music is about time and place and the way that it affects you. There’s just something about it. There’s just some spirit that somebody conjures up and then it floats out at you and helps you or hinders you throughout your life. It’s either Handel’s Messiah or it’s “All Out of Love” by Air Supply.

Music is just fucking insane. It’s everything. Music is like this: It’s always seemed to me to be one of the direct descendants of the thing in the universe that’s making everything work. It’s like the direct child of … life, [of] what being “people” is all about. It’s incredibly human but it touches things that are around us anyway. [pauses, then quietly] It’s hard to explain.

Give it a shot.

It gets into your blood. It could be [the Ohio Express’] “Yummy Yummy Yummy” or whatever. It gets in. It’s not like paintings and it’s not like sculptures, although those are really amazing and powerful. But I identify with music most.

And is live music the next degree of intensity?

Oh yeah, if they’re singing to me. You never hear it again, but you never forget it. I mean, you never forget it. It’s like the first time your mother cries in front of you. But I like making [music] and … I want the music to live live, even be written live, so it’s always forming, it’s ever unfolding.

The king of improvisation is [the late Qawwali singer] Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan — the most I’ve ever been filled with any performer’s energy. I have over $500 of his stuff. And I never got to see Keith Jarrett, but there was a time when he was my big hero for the same reason. Big, huge improvisation. Improvisation is something that I identify with.

Which of your new songs is your favorite? Is there one that you can’t wait to get to in your live set?

Not yet. I give each song pretty much the same attention, and I have the same reservations and the same carefulness about making sure I bring out its best. No favorites.

What’s a song by another artist that you wish you’d written, that completely devastates you?

Most of Nina Simone’s songs completely devastate me, although she didn’t write [most of] them. A lot of things that Dylan did are so impressionistic, even though his originals are supposed to be folky. Like “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands”: If I was a woman and he sang that to me, I’d be like, “Whatever you want, Bob. You want casual sex whenever you want it and still be with your wife? I don’t care.”

I’d like to write something like “Moanin’ for My Baby” by Howlin’ Wolf, and I’d also like to write something like [Gerry and the Pacemakers’] “You’ll Never Walk Alone.” I have schoolgirl crushes on a lot of songs that never seem to go away. Lots of Cocteau Twins. That’s somebody I got to tell exactly what I thought of them.

Where were they playing?

In Los Angeles, a long time ago on the Heaven or Las Vegas tour. I’m immensely in love with their originality, their shyness. … But … um … the Smiths! [stands up abruptly, then sits back down] I wish I’d written half the fucking Smiths catalog. There are so many: “I Know It’s Over”; I wish I’d written “How Soon Is Now?” I wish I’d written “Holidays in the Sun” by the Sex Pistols. I could go on forever, and I know you don’t have forever.

Maybe sleep on it. I’m curious, do you sleep a lot? No, I don’t.

Is your mind constantly racing? Are you always just … fast forward?

Have you ever seen those film montages when a guy’s going crazy, and it just gets faster and faster and…

Yeah, sure, that’s exactly what I mean. It’s exactly like that. It’s like, I don’t want to miss a thing, and [I get the] feeling that I will miss something. But usually I’m wrong. [laughs] But when I do sleep, I sleep hard and have the best dreams.

Do you remember your dreams?

Sometimes, and they become the basis for a lot of my learning. That comes along with my development as a human being. Lately I’ve been having a lot of killer dreams — like a killer is coming after me or I have to confront a killer. And when a killer is coming after me, what am I going to have to do? To kill him.

Interesting. What do you think that means? That something in me is going to be murdered. That a psychic killer is coming. Actually, I met him. Sometimes I meet people inside of me that don’t like me; sometimes I meet people inside of me that want to make love with me more than anything; sometimes I meet the most bizarre animals and am in the most bizarre situations.

One dream, I met a serial killer who lived out in a small town in, like, Virginia. A small suburban town, very nice, white picket fence. And he lived in the town in a church with the pews taken out. And he was an artist.

You remember this much detail? Just wait. He was a very short young man, probably about 28 years old with thinning black hair that I think he was ashamed of. He also had all of these photos of these people mangled beyond belief, carved up, dissected alive. They were still alive in these photos, and there was a wall of all of these seductively beautiful, textured, processed black-and-white photos. One man had been made into a basket. One man had been totally deboned but still kept alive, and his skin had been made into a basket upon which his head stood, looking straight into the camera. And right before he died, this snapshot was taken. And this is what this guy’s job was. And my task in the dream, I was the person that saw this amazing horror and this amazing pain. The photographs were screaming, and all of this madness, all of this waste at the hands of this person with a warped soul.

The irony of the dream was that his self-esteem was nothing, and he was saying, “This sucks. This is horrible. I don’t even want to show you.” I was so afraid of him and wanted to keep him in the same place long enough for the police to get him and take him away — while not being killed myself. Obviously. [laughs] So in order to be cool I had to ultimately be compassionate and point out the details in the picture where I felt there was brilliance and really good workmanship — all the while feeling that I would vomit any second, all the while so scared I thought I would cry. And that was the dream.

Sometimes I have really rhapsodic dreams, and sometimes I have little bits of memory … but lately it’s been killer dreams, and the police almost don’t come in time, although they do come in time. And then I met a woman inside me that hates me. I met the girl, I met the person that doesn’t like me, and then I met this person who was so lascivious sexually that she masturbates publicly all of the time, like she’s fixing her hair. And she looks beautiful doing it and really great, but everyone’s around her and she’s practically naked. I’m pretty transfixed by [dreams]. I link them to the way I perform. I don’t see any separation, because when you sing there’s a psychic journey that happens.

Do you write a lot of poetry?

I garner my songs from my poetry. If anything looks like it’s vibrating, yeah. But it’s a raw thing.

Was the Live at Sin-é EP, released in November of ’93, supposed to hold people over until the album comes out?

No, it served that purpose, but no, it’s just because I love that place.

How often have you played there?

I’ve played there a lot. I played there for over a year. At first I couldn’t get a slot. Shane [Doyle], the owner, had too many demos to listen to. I gave him a demo and a review, which is something I never ever, ever fucking do: pay credence to any one journalist’s opinion. But this was a good review. [laughs] Some positive, some negative. Mainly the negative stuff was my fault. So I thought that maybe I could get a gig at this little place because I wanted to play in little places to establish my sound and do the work and learn how to sing the way I wanted to sing. Because I didn’t have any teachers. There were teachers around Sin-é to teach what I needed to learn, but Shane couldn’t be bothered.

Then somebody crapped out on a bunch of Monday nights and my friend Daniel Harnett got me in. He said, “I’m doing one, and so you can do one too.” I was like, “Wow, thank you.” As it turned out, that was it. Bang! I really worked my ass off to get that gig and get others and to make money. How did you hook up with Columbia Records? They came to me. I didn’t intend for them to. I was just making music. Were they the only label that came to you? Nope. I met Clive Davis. Shook his hand. I met Seymour Stein. Seymour’s at Sire; Clive is at Arista. A lot of people were interested. I met somebody from RCA. Peter Koepke at London. Were they in the audience at your shows? Then they’d come up to you afterward? Yeah, and I didn’t really like it. I didn’t like Clive showing up in a limousine on the Lower East Side, in a fine suit. Poor guy — it was so hot in that fucking room. This was Sin-é, right? Yep, you were there — like a fucking furnace. In the middle of the fucking summer. I had my shirt off; the guy’s still in his work clothes ’cause his life is fully air-conditioned.

Did you have any misgivings about signing? Of course I did. Being brought up around the music business in Los Angeles, you see the turnover of people being signed and dropped day after day after day, and it’s all written off as a tax loss. To the company, it’s no sweat off their nose.

But here in New York it’s more about the work, and you don’t get anywhere without the work and that’s what I was doing. But I had misgivings about the size of the places. I had misgivings about my deservedness, about how good I was. I had misgivings about who they thought I was and what they thought I was. And how I wasn’t what they thought. At all.

Which is? Don’t record companies think that every male solo performer with a guitar is the New Dylan?

No, they thought I was the second coming of Tim Buckley. [quietly] That’s what I thought they thought.

Is that a recurring worry of yours?

It was that as a child. But now I’m totally immersed in what I do. If someone asks a question about it, I just tell them as much truth about things as I know. I had no misgivings once I saw my first and only liaison to Columbia Records, [former head of A&R] Steve Berkowitz. He was there from a pretty early stage, just listening. Which is what he does. Because he loves music. And he’s smart. And he’s smart enough to work this fucking gig at Columbia and to do a good job. The personnel here [at Columbia] are what really changed my worries, but I’m really worried up until, like, now. How would you describe your sound? I can’t explain it because I’m actually confused. It’s not really a tremendous literary feat to describe it. It’s just an amalgam of everything I’ve ever loved and everything that’s ever inspired me. I’m using that now. How do the Columbia folks describe you? They don’t know. At a recent convention I played in Boca Raton for A&R folks at like 11 in the morning, the guy that introduced me said, “We really don’t know what this is. We don’t know what kind of record he’s gonna make. We just know he has to make it.” … a.k.a. “Introducing the boy genius…” I’m not a boy genius. I’m neither one, actually. But I’m aware that these people have to move units. I’m aware that this company, by inertia alone, has an agenda. That it can function without me, and I can function without it. But there’s a certain thing that I can’t have without it, and that’s making little plastic discs and traveling the world and being a musician, and they seem to want me. A lot. And I feel that where I’m going is worthwhile, that maybe when I get there this all will have been … whatever crappy shit I’ve ever done will be redeemed. Do you think you’ll ever get there? Sure. Or you’ll find me swinging from somebody’s dressing room [laughs] with a big blue arm holding a Jam tape.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Australie

Excerpts from the article in the Sydney Telegraph, Saturday 6th June, 1997, pp 38-39. It contained an interesting interview with John Pope, Jeff's Australian tour manager, and Donny Ienner, Head of Columbia Records. (thanks to Christine Warren)

THE LAST GOODBYE Music writer Dino Scatena examines an ironic finale.

The tragic details of Jeff Buckley's final few moments read like an overly dramatic draft for one of the artist's video clips. The imagery could have served as a perfect visual counterpart to his most famous song, Last Goodbye. A carefree Buckley, laughing and singing as he walks fully clothed into the Mississippi River, floating on his back until the water's swirling hidden life-force rises to hug his fragile frame and lead it into eternity. Les détails tragiques des derniers moments de Jeff Buckley sont comme un brouillon extrèmement dramatique d'un clip vidéo de l'artiste. L'image aurait pu servir de parfait équivalent visuel pour sa chanson la plus célèbre : Last Goodbye. Un Buckley insousciant, riant et chantant comme il va tout habillé dans le Mississipi, flottant sur le dos jusqu'au moment où la force vitale cachée dans l'eau tourbillonnante s'élève pour étreindre sa fragile charpente et la conduire dans l'éternité.

Buckley would have hated such a storyboard; too cliched, too grandiose. The 30-year-old singer/songwriter always strived to make his work uncluttered, simple, its power left to be carried through the innate beauty of his poetry and pure angelic voice. Buckley aurait détesté un tel story board ; trop cliché, trop grandiose. Le chanteur/songwriter, âgé de 30 ans, s'est toujours efforcé de désencombrer son travail, simple, son pouvoir se laissait porter par la beauté innée de sa poésie et de sa voix pure et angélique.

The extraordinary circumstances surrounding the death of Jeff Buckley has once again sent a generation of rock fans around the world into deep mourning. It's an all too familiar tale: an artist with a seemingly mystic gift, a tortured and tormented soul whose presence is whisked away from us before its full potential is realised. Les circonstances extraordianaires entourant la mort de Jeff Buckley a plongé à nouveau une génération de fans de rock du monde entier dans un deuil profond.

(...)

As it's turned out, Buckley was only on this world long enough to release a single album, Grace will remain one of the most astonishing and well-rounded debuts of the modern rock age. Vu la tournure des choses, Buckley a été dans ce monde seulement assez longtemps pour sortir un unique album, Grace restera un des premiers albums les plus étonnants et les mieux tournés du rock de l'âge moderne.

Of course, all the tragedy surrounding Buckley's passing is compounded by the fact that his father, Tim Buckley, met a similar premature end. Tim Buckley, who many still hail as the most original folk singer of his generation, died of a drug overdose in 1975 at the age of 28. Bien sûr, toute la tragédie entourant le décès de Buckley est constituée du fait que son père, Tim Buckley, eut également une fin prématurée.Tim Buckley, que beaucoup proclament encore comme le plus original chanteur folk de sa génération, est mort d'une overdose de drogue en 1975 à l'âge de 28 ans.

I lost myself on a cool damp night I gave myself in that misty light Was hypnotised by a strange delight Under a lilac tree (Lilac Wine)

Jeff Buckley's two visits to Sydney left an enduring impression. He came twice within six months, first in August of 1995 and then in February of last year. That first brief trip came on the back of an extended European tour. "I was getting tired of it in the last moments of playing in Europe, but it's entirely new here and I've had time to convalesce," he told a reporter on arrival. Les deux passages de Jeff Buckley à Sydney ont laissé une impression durable. Il est venu deux fois en 6 mois, d'abord en août 1995 puis en février de l'année dernière. Ce premier et bref voyage venait derrière une grande tournée européenne. "Je commençais à fatiguer les dernières fois où j'ai joué en Europe, mais c'est entièrement nouveau ici et j'ai eu le temps de me remettre", dit-il à un reporter à son arrivée.

Over the next few days, he gave two unforgettable performances: one at a small club called the Lounge in Melbourne and the other at Sydney's Metro nightclub. To those present, the Metro show on August 28 rates as one of the greatest musical performances ever witnessed in this city. In a magical 90 minutes, Buckley and his three-piece band delivered a remarkable set of light and shade featuring much of the Grace album as well as the aggressive covers of MC5's Kick Out the Jams" and Big Star's "Kangaroo". Buckley's pure, acrobatic voice sounded all the more extraordinary in the flesh. "You could hear a pin drop," recalled tour manager John Pope. "He held the audience in the palm of his hand. He'd take you on the ride with him. He'd lift you and take you down. He paced his gigs with finesse. When he walked on to a stage, he felt a responsibility, but it wasn't to the audience. It was to something else. God knows what." Les neuf jours suivants, il donna deux performances inoubliables : une dans un petit club appelé "the Lounge in Melbourne" et l'autre au Sydney's Metro nightclub. A ceux qui étaient présents, le show du Metro en août demeure une des plus extraordinaires performances jamais vue dans cette ville. En 90 minutes magiques, Buckley et les trois autres membres du groupe offrèrent un remarquable set de lumères et d'ombres jouant la plupart des chansons de l'album "Grace" comme des reprises agressives de "Kick Out the Jams" des MC5 et de "Kangaroo" de Big Star. La voix pure et acrobatique de Buckley sonnait le plus extraordinairement possible dans la salle. "Vous pouviez entendre une mouche voler" rappelle le tour manager John Pope. "Il tenait le public dans la paume de sa main. Il vous emmenait faire le voyage avec lui. Il vous levait et vous reposait. Il dosait ses shows avec finesse. Quand il montait sur scène, il sentait une responsabilité, mais pas envers le public. C'était autre chose. Dieu sait quoi."

"There was high anticipation which was rewarded 10-fold when he played, added Jen Brennan, manager of teh night's local support act Crow. "He just moved a lot of people. It was quite extraordinary. It's not often that you get a crowd at the Metro that's so silent and still. It was serene and very powerful." "Il y avait une grande anticipation qui avait été 10 fois récompensée quand il a joué", ajoute Jen Brennan, manager du Crow."Il a touché un grand nombre de personnes. C'était vraiment extraordinaire.Ce n'est pas souvent qu'on voit une foule au Metro qui soit si silencieuse et si calme. C'était serein et très puissant."

Indeed a couple of nights later at the Lounge show in Melbourne, the venue's management found it necessary to turn off the cash registers because their collective clanging messed with the ambience. De fait, deux nuits plus tard au Lounge show de Melbourne, le management trouva nécessaire de fermer les caisses enregistreuses parce que leur bruit collectif cassait l'ambiance.

That first visit was meant to be a simply a quick promotional trip to push Grace, but such was the impact of the Metro show that Buckley was persuaded to return to Sydney and play two extra gigs at the Phoenician Club to quench the city's sudden fascination with him. Cette première visite était censée être simplement un rapide voyage voyage promotionnel pour pousser Grace, mais l'impact au Metro show a été tel qu'on a convaincu Buckley de revenir à Sydney et de jouer deux nouveaux shows au Phoenician club étancher la soudaine fascination de la ville envers lui.

Within a few days of arriving, Buckley was gone. But he'd loved his time here and promised to return as soon as he could. Buckley kept his word and was back in February for a full-scale national tour. Peu de temps après son arrivée, Buckley était parti. Mais il avait adoré le temps passé ici et avait promis de revenir aussi vite que possible. Buckley tint parole et était de retour en février pour une tournée nationale.

It was now two years since the release of Grace and the pressures of life on the road as a high-profile recording artist were starting to show. "The whole Grace period has just been madness," he told the Daily Telegraph at the time. "I had no idea how completely crazy in the head I was until I came back and touched ground. I lost a lot of blood out there, meaning some things fell apart, some things got stronger. I think maybe I sensed my life would be altered forever, but not in any of the shapes it has. It's just like having a child. You can plan on it for years and years and think about it and daydream about it but when it actually happens, the ripple it causes in your life is really transforming." Cela faisait maintenant deux ans que Grace était sorti et les pressions de la vie en tournée d'un artiste de studio commençaient à se faire sentir. "Toute la période Grace a été de la folie", disait-il au Daily Telegraph à ce moment. "Je ne me rendais pas compte que j'étais complètement fou dans ma tête jusqu'à ce que je revienne et que je touche le sol. J'ai perdu beaucoup de sang là-bas, je veux dire que des choses ont disparu, certaines choses sont plus fortes. Je crois peut-être que je sentais que ma vie serait altérée pour toujours, mais pas du tout dans le sens où elle l'a été. C'est juste comme d'avoir un enfant. Vous pouvez le planifier sur des années et des années et penser à ça et rêver à ça mais en fait quand cela arrive, l'onde de choc que ça cause dans votre vie et vraiment "transformante"."

Although that second tour may have been a bit flat on stage, Buckley was still in good spirits, the same free-wheeling reckless self. He had his girlfriend with him this time, a violinist named Joan from a band called the Dambuilders. There was a screaming match back at the band's hotel one night when one of Buckley's bandmates came back to his room to find the singer and his girlfriend had trashed the room and had sex in both beds. Another night when Joan's band was playing a show at the Annandale hotel, Buckley went down and took care of the light show. When the Dambuilders started trashing their own instruments at the end of the show, Buckley abandoned his lighting duites and ran up on stage and helped them do it right. Même si cette seconde tournée peut avoir été un peu plate sur scène, Buckley était toujours dans de bons esprits, le même personnage imprudent en roue libre. Il avait sa copine avec lui cette fois, une violoniste nommée Joan dun groupe appelé the Dambuilders. Il y eut une effrayante baguarre à l'hôtel du groupe une nuit quand une des roadies de Buckley revint dans sa chambre pour s'apercevoir que le chanteur et sa copine avaient dégueulassé la chambre et fait l'amour dans les deux lits. Une autre nuit quand le groupe de Joan jouait un show à l'hôtel Annandale, Buckley descendit et s'occupa des lumières. Quand les Dambuilders commencèrent à détruire leurs propres instruments à la fin du show, Buckley abandonna la lumière et couru sur la scène pour les aider à bien faire.

Friends all describe Buckley as a warm, loving, open soul but the singer was often apprehensive when first approached by strangers. John Pope, who as tour manager for both visits spent virtually every day with Buckley while he was in Australia, described how the artist might appear cold as ice at first and then suddenly swing to the other extreme. "Someone on the street might say:'Are you Jeff Buckley?'" Pope explained. "And one day he night say: 'No he's over there, I saw him just go around the corner.' Or sometimes he might go, 'Yeah, I'm him' or 'Leave me alone'. Then they might say something funny and he'd open straight up to them and talk to them like they're long lost friends. It went that way in personal life, business life and with people he'd never met before." Ses amis décrivent tous Buckley comme une âme chaude, amoureuse et ouverte mais le chanteur appréhendait souvent ses premières approches avec des étrangers. John Pope, qui en tant que Tour Manager pour les deux passages passa virtuellement chaque jour avec Buckley pendant qu'il était en Australie, décrit comment l'artiste pouvait apparaître froid comme de la glace au début puis soudainement aller vers l'autre extrème. "Quelqu'un dans la rue pouvait dire "êtes-vous Jeff Buckley ?"", explique Pope. "Et un jour il pouvait répondre : "Non, c'est par là, je l'ai vu juste tourner au coin." Ou parfois ça pouvait être "ouais, c'est moi" ou "Laissez-moi tranquille". Puis ils pouvaient dire quelque chose de drôle alors il s'ouvrait directement à eux comme s'ils étaient de vieux amis perdus de vus. C'était comme ça dans sa vie personnelle, professionnelle et avec des gens qu'il n'avait jamais vus avant."

Pope's fondest personal memory of Buckley came during the first trip. The singer was furious when he found out that his tour manager hadn't told him that it was his birthday. Buckley promptly organised a penis-shaped cake and presented it to Pope on stage in Melbourne before shoving his face in the gift. Pope holds dear a photo of the pait on stage together, Buckley covered in cake and smiling broadly. Le premier souvenir personnel de Pope concernant Buckley date du premier voyage. Le chanteur était furieux quand il découvrit que son Tour Manager ne lui avait pas dit que c'était son anniversaire. Buckley organisa sur-le-champ un gâteau en forme de penis et le présenta à Pope sur scène à Melbourne avant de pousser son visage dans son cadeau. Pope montre tendrement une photo de l'événement sur scène ensemble, Buckley couvert de gateau et souriant vaguement.

"I can imagine him doing exactly what he did," Pope offered in reference to the circumstances of Buckley's disappearance, recalling the time he tried to talk the singer out of going for a night swim at Coolangatta Beach. "From when I knew him, you'd say: 'You shouldn't do that Jeff.' And he'd go:'Nah, it'll be all right. Don't worry about it.' And off he'd go. He was carefree and easy-going like that about life. "There was an edge to him that comes with creative people. He was definitely touched. He'd have those moments of of madness like any artisitc person does. But there was no self-destructiveness in it at all." "Je peux l'imaginer en train de faire exactement ce qu'il a fait", Pope fait référence aux circonstances de la disparition de Buckley, rappelant le temps où il essayait de convaincre le chanteur de ne pas aller nager à Coolangatta Beach. "Tel que je le connais, vous auriez dit : "Tu ne devrais pas faire ça Jeff". Et il aurait répondu : "Bah, ça va aller. Ne t'inquiète pas de ça". Et il aurait été. Il était imprudent et insousciant comme ça avec la vie. "Il y avait un côté chez lui qui est lié aux gens créatifs. Il était définitivement atteint. Il avait ces moments de folie comme tout artiste en a. Mais il n'y avait pas d'auto-destruction là-dedans du tout."

They're waiting for you Like I waited for mine And nobody ever came. (Dream Brother)

Jeff Buckley only ever met his famous father once. He spent a week with Tim, who left his mother Mary Guibert only a week after she gave birth to their only child, in April of 1975 when he was eight. Two months later, his father was dead. The weight his father's shadow cast on his life was the primary reason it took Jeff so long to take the leap into the limelight. "I knew there would be [comparisons] from the time I was a small child," Jeff once revealed. "From the time that his manager started calling my house when I was six or seven. I found my grandmother's guitar and [the manager] started calling the house:'Has he written songs yet?' So I've been waiting and doing the maths in my head about the inevitable comparisons all my life. But I don't care." Jeff a seulement rencontra son célèbre père seulement une fois. Il passa une semaine avec Tim, qui quitta sa mère Mary Guibert seulement une semaine après qu'elle ait donné naissance à son unique enfant, en avril 1975 quand il avait 8 ans. Deux mois plus tard, son père était mort. Le poids de l'ombre de la personnalité son père sur sa vie fut la principale raison pour laquelle cela prit si longtemps à Jeff de sortir de l'ombre. "Je savais qu'il y aurait des comparaisons depuis que je suis enfant," révéla Jeff un jour. "A partir du moment où son manager a commencé à appeler chez moi quand j'avais 6 ou 7 ans. J'ai trouvé la guitare de ma grand-mère et le manager a commencé à appeler à la maison : "A-t-il déjà écrit des chansons ?" Alors j'ai attendu et fait le calcul dans ma tête à propos de l'inévitable comparaison toute ma vie. Mais je m'en fiche."

Buckley was never comfortable discussing his father, deeply resented the fact that he wasn't invited to the funeral. But in 1991, he made an unannounced appearance at a Tim Buckley tribute concert in Brooklyn and performed a moving solo version of his father's I Never Asked to be Your Mountain. "I both admired and hated it," the young Buckley said afterwards on the song written about his parents' relationship. "That's why I did it. It was something really private to me. I figured that if I went to the tribute and sang and paid my respects, I could be done with it." Buckley ne se sentait jamais à l'aise pour parler de son père, ressentant profondément le fait qu'il ne fut pas invité aux funérailles. Mais en 1991, il fit une apparition surprise à un concert hommage à Tim Buckley à Brooklyn et joua une version solo "bougeante" de la chanson de son père "I Never Asked to Be your Mountain". "Je l'admirais et la haïssais à la fois," disait le jeune Buckley après-coup de la chanson écrite sur la relation de ses parents. "C'est pour ça que je l'ai fait. C'était quelque chose de vraiment très privé pour moi. Je m'imaginais que si je venais à l'hommage et chantais et payais mes respects, je pouvais en être quitte".

It's night time coming I'm not afraid to die ... My love, now the rain is falling I believe my time has come It reminds me of the pain I might leave behind. (Grace)

Jeff Buckley signed to Columbia records home to the likes of Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen, in 1993 and soon after released the EP Live At The Sin(e). Jeff Buckley signa avec Columbia Records en 1993 à l'instar de Bob Dylan et Bruce Springsteen et peu après sortit le EP "Live at Sin-é".

In an exclusive interview with the Daily Telegraph yesterday, an emotional Donny Ienner -- head of Columbia Records and the man directly responsible for signing Buckley -- shared his reminiscences aof that early period. "I remember the first time I went down to see Jeff after a few people had told me about his performances at SINE, I was so taken that night by the depth of his artist. Of all the artists that I've ever personally signed, Jeff made the most immediate impact on my life. I felt that his reverence for the past, not to mention obviously the opportunites for the future, was incredible. He knew every record of Miles Davis and Edith Piaf and opera records and classical records and Led Zeppelin records. He was just such a great teacher of diverse music. He defies any sort of characterisation or trend. He had that at a very, very early age and the impact that he made on the world with just an EP and an album is going to be felt for decades to come. Jeff never worried about rock stardom, never worried about money, and never worried about the things that a lot of young artists worry about today. He was really worried about making sure his integrity was intact at all times. He was just an incredible thing." Dans une interview exclusive avec le Daily Telegraph hier, un Donny Ienner ému - patron de Columbia Records et l'homme directement responsable du contrat de Buckley - partageait ses souvenirs de cette récente période. "Je me souviens de la première fois que je suis venu voir Jeff après que quelques personnes m'aient parlé de ses performances au Sin-é, j'ai été si frappé cette nuit-là par la profondeur de cet artiste. De tous les artistes que j'ai personnellement signés, Jeff a eu l'imapct le plus immédiat dans ma vie. Je sentais que sa révérence pour le passé, pour ne pas mentionner d'ailleurs les opportunités pour le futur, était incroyable. Il connaissait chaque disque de Miles Davis et Edith Piaf et des disques d'opéra et des disques classiques et les disques de Led Zeppelin. C'était un super professeur de diverses musiques. Il défie toutes sortes de caractérisation ou de tendance. Il a eu ça très très jeune et l'impact qu'il a eu sur le monde avec seulement un EP et un album s'estimera dans les décennies à venir. Jeff ne s'est jamais inquiété de la célébrité rock, ne s'est jamais inquiété de l'argent, ne s'est jamais inquiété des choses qui inquiètent beaucoup de jeunes artistes aujourd'hui. Il s'inquiétait vraiment d'être assuré de garder tout le temps intacte son intégrité. Il était juste une chose incroyable."

Ienner also took the opportunity to reject widespread rumours that Buckley had been depressed in the weeks leading up to his disappearance because of problems with his record comapny over the shape his follow up to Grace should take. "I think he was in a good place in terms of making his second record," Ienner said. "The thing that I personally promised him when he signed to Columbia records was that he could take all the time he needed in between his records and we would not interfere on any level. He had over 100 songs and he was ready to go in at the end of June to make his record. He was in wonderful spirits, he was having an amazingly good time spiritually, emotionally and professionally down in Memphis (where Buckley had been since February)". Ienner a également saisi l'opportunité de rejeter les rumeurs très répandues sur une déprime de Buckley dans les semaines précédant sa disparition à cause de problèmes avec sa maison de disque, au sujet de la forme que devait prendre l'album succédant à Grace. "Je pense qu'il était bien placé en vue de faire son second album," a dit Ienner. "La chose que je lui ai personnellement promise quand il a signé à Colombia Records était qu'il pourrait prendre tout le temps dont il avait besoin entre ses albums et que nous n'interférerions pas à aucun niveau. Il avait plus de 100 chansons et il était prêt à aller au bout à la fin du mois de juin pour faire son disque. Il était dans un état d'esprit merveilleux, il passait un étonnemment bon moment spirituellement, émotionnellement et professionnellement à Memphis (où Buckley était depuis février)".

Ienner confirmed that late last year, Buckley completed seven new songs during sessions in New York with producer and former Television lynch-pin, Tom Verlaine. "We have no plans to release anything right now. From what I understand from the people he's been working with, there are in excess of 50 or 60 songs that he was working on. So there's a wonderful legacy that he's left behind." Ienner a confirmé que, à la fin de l'année dernière, Buckley a terminé 7 nouvelles chansons pendant les sessions à New York avec le producteur et le fondateur de Television Tom Verlaine. "Nous n'avons pas prévu de le sortir pour le moment.D'après ce que j'ai compris des gens avec qui il travaillait, il y a en plus 50 ou 60 chansons sur lesquelles il travaillait. C'est donc un legs merveilleux qu'il laisse derrière lui."

Looking out the door I see the rain fall upon the funeral mourners Parading in a wake of sad relations as their shoes fill up with water Maybe I'm too young to keep good love from going wrong But tonight you're on my mind so you'll never know (Lover, You Should've Come Over)

Jeff Buckley is gone but, like all the other great artists who were cut down in their prime, his music will long outlive his tragically short life. Jeff Buckley est parti mais, comme tous les autres grands artistes fauchés dans leur force de l'âge, sa musique survivra longtemps à sa vie tragiquement courte.

(Translation: Jeff Buckley is gone but, like all other great artists cut down in their prime, his music will long outlast his tragically short life.)

#jeff buckley#jeffbuckley#Australia tribute#Australie#Excerpts from the article in the Sydney Telegraph#Saturday 6th June#1997#pp 38-39.#06.06.1997

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

LAST GOODBYE the lost Jeff Buckley interview

One of the most revealing – and spine-chilling – interviews of Jeff Buckley’s short life was conducted for a fanzine with a small readership. Phil Smith resurrects it here, with thanks to Andrew Truth for the interview and extensive contributions

In 1995, fanzine journalism was giving the established music press a run for its money. Andrew Truth had been producing Plane Truth since 1988 but issue 15 (circulation: 500) was to be his last. It had interviews with the usual unusual selection of bands, some fondly remembered and some largely forgotten.

Lurking at the back of the fanzine was an encounter with Jeff Buckley, son of Tim and on the way to becoming a legend in his own right. Andrew had conducted the interview on 3 September 1994, before Buckley’s show at what was then The Hop & Grape (now part of Manchester Academy). Buckley had only just released Grace and started touring with a full band, which Andrew remembers him enthusing about. The album was yet to slow-burn its way into the hearts of millions. He had been recording a Mark Radcliffe session and playing Reading Festival and likened the part he played at the latter to being “a circus performer”. He was about to leave for the continent for further dates. His father’s reputation preceded him and for that reason, Andrew steered away from questions about family. They got on like a house on fire, Buckley rambling excitedly about his favourite music, playing live, his choice of cover versions, songwriting and immortality.

Buckley introduced himself by impulsively diving onto Andrew’s cafeteria table. He launched unprompted and with a distant air into part of one of his favourite interview topics, a solo LP by Deep Purple’s Jon Lord, as if transmitting thoughts from a superior galaxy and with a mischievous glint in his eyes. He dabbed sandalwood oil behind his ear while mimicking a cockney accent and singing jauntily: “‘Now we’ve made it, I’d like to do my orchestral piece called Gemini Suite about the signs of the zodiac.’ [Lord’s LP is] Great! It’s partly Bonanza, partly every horrible cliché. Like in Warner Brothers cartoons, Bugs Bunny music. It’s the funniest shit alive, all that 70s stuff. I can’t listen to it for long [though]. There’s a difference between indulgence and exploration.”

It had been Buckley’s questing approach in addition to his poetic soul and natural vocal talent that had drawn Andrew towards him at this early stage in his international career. Buckley settled into the interview, describing his nomadic upbringing as “a preparation and a curse, but everyone’s childhood is. It’s made it easier [for me to tour]. You’re the stranger constantly. People will find occasions where they’re readily accepted but other times, equally [the] weight of hostility comes towards you for no reason at all. I still attract the same things from childhood. People come to the shows and either run away screaming or really like it.”

Andrew expressed his contempt for middle-ground mediocrity in music. Buckley was more nuanced in his response, describing its fleeting effect: “Nothing [from the middle ground] comes to mind, that is ’cos I’ve forgotten it already. I’ve forgotten the effect and which art it was that gave me the effect. Either you remember Bob Dylan or you remember Michael Bolton.” Bolton was another Buckley interview hobby horse and appears to have been the bane of his life, and he was arguably a collective figure of hate for all alternative music fans at the time.

At the gig, Andrew described Buckley as bouncing about in a style that induced cries of “Kangaroo!”, his face dramatic and furrowed in anguish, seeming to curse injustices with disbelief. “People project tremendous amounts of personal low self-esteem and high self-esteem upon the stage, in equal parts sometimes. That’s the catharsis of going to a live show. If the performer is right, this is very co-dependent, but people go there to unload. There is this loud person who has come to a few of my gigs and her friends insist that she’s a very nice person but she can’t help but shout at me up on the stage. It’s something I just accept. It’s not like when Murphy’s Law played at The Plaza and four or five fights erupted within the space of 46 minutes. I don’t look out to see whether I’m connecting because it’s not up to me. I look out to see where the music should go. If the crowd is hot because their skin is hot due to the temperature, the set will be different. Or if it’s very cold outside and still, I’ll want to be the fireplace as best I can though sometimes I can’t accomplish it. I’m aware of the energy in the room. Moods and music fly about of their own will and they have no order and you can be either open or closed to them and that’s how the gig will go. Either from the stage or the audience, people open to emotions, movement, stories, feeling and dancing.”

Andrew asked Buckley about the unusually high number of cover versions on his first couple of releases. “It’s usually everything about [the song that attracts me], not just one thing. It’s different in the case of [Van Morrison’s] The Way Young Lovers Do. That came about because my friend Michael, who eventually joined the band, had a dream about me and him singing [it]. On a whim, I got it together and performed it one night. Then it became something else because the tempo I liked, the feel of it; the words and the song got into me. Any time I take a cover and wear it on my sleeve, it’s because it had something to do with my life and still marks a time in my life when I needed that song more than anything ever.”

Andrew expressed some shock at how good a rescue job Buckley had done with his Lilac Wine cover, as he previously disliked the Elkie Brooks version. Buckley said: “The version I’ve heard is Nina Simone’s. I’m not even sure who Elkie Brooks is. I don’t think it’s always a fair decision to have homogeneity for its own sake. I think that human beings contain many people… I do believe that there’s this one soul that lies directly through Edith Piaf and the Sex Pistols, I really know that exists: Joni Mitchell and John Cage; Billie Holiday and Bad Brains. An album in itself is a moment and the music may require for me to make an album that’s totally homogenised but not as a rule. It’s good to be varied because without knowing what sides there are to you, knowing your depths, you pretty much die. You never change and you stay in the same unbeatable format but, sooner or later, you become obsolete.”

Failure to evolve is to stymie yourself, suggested Andrew.

“That’s true. I’m not even that concerned with changing,” Jeff replied. “Just with discovery, because through discovering you may stay on one thing for a long time. Just evolving is important. Deliberately changing all the time is like making off with somebody who must change position in order to get into every [sexual] position and you never get anything started. ‘Would you please keep still, throw away the Kama Sutra and love my ass!’”

Buckley confessed to a couple of songs to which he would feel unable to add anything: “Parchment Farm Blues by Bukka White and Well I Wonder by The Smiths because I always end up doing it exactly like Morrissey does. The impetus for having covers was necessity. In the middle of a show taking people into a world that was completely my world, ‘boom’, right over there we’re into I Know It’s Over from The Queen Is Dead.”

In a segment of the interview which Andrew admits makes him a little queasy now, he picked up on Buckley’s Eternal Life and asked him if he desired immortality. Tim Buckley died young of a heroin overdose and his son was to tragically drown in 1997, only a few years after the Plane Truth interview.

“It is possible and it happens all the time, but just not in the way you want or expect it,” Buckley Jr said. “Beyond death, I know nothing but in human life… some people have a love for people around them that is so powerful and carries so many gifts with it that even when they die, people are still accomplishing things through this person’s love in them, because this person said, ‘I see you’re a writer. I see this postcard here and you’re killing me in this, you’re a great writer.’ And he’s saying, ‘I never thought about writing before. ‘But anyway, you’re a great writer and this is a great piece of work. I don’t even want to touch War And Peace, this is it,’ and, ‘boom’, he gets hit by a car and this person goes on to be a great writer or remembers that belief, against his own hope. It’s very strange, in that way, he’ll become immortal, he’ll always be remembered. He’ll be alive in people’s hearts, inside people.

“Then there’s books, records, movies, images. Here’s immortality in a nutshell: Marilyn Monroe, James Dean. They’re all around you but they don’t exist. That’s immortality in my cynical world. That’s Tinsel Town immortality, which is bullshit. They’ve lost immortality because they’ve lost their appearance as mortals. They’re symbols, gods, tools and puppets for people. There’s a fine line between being a god and a puppet...The Bible is used as a puppet and it’s untouchable and sacred but people use it as a pair of roller-skates or joke toilet paper with a psalm on every sheet. Being mortal and rooted in the earth is a very excruciating joy and not a lot of people can take it. Sometimes they just want to be famous, with no substance underneath, no work, no reason. To be famous and known and loved. They think it’s being loved but it’s just being worshipped and idolised and that’s not even being understood. It’s not even in the ballpark. It’s better to have people around you who understand you and when you come up to people in the street and talk about bagels and talk about the game, to have that connection there, it’s very important to me.

“If I wanted to be famous, I’d assassinate the President. There’s no life in it. There’s nothing wrong with being famous for something you do well or uniquely like if I invented the cure for AIDS, I wouldn’t mind being very famous. It’d be a great achievement. Or if I wrote a song that everyone loved, I wouldn’t mind that. It wouldn’t mean everything. That wouldn’t be the object or I’d be a junkie for fame, ‘I wasn’t famous for my orange juice song. It’s a great song but nobody likes it! I must suck!’ I have to be attuned to that and must have an everlasting relationship with this particular thing that there’s a public and then there’s me. At any given time, I am the public and Evan Dando [Lemonheads] is him and I understand that exchange. It’s a very strange arena and lots of people get thrown to the lions. Lots of people come away victorious for a time but then they’re out of the arena, that’s the end of it.”

Andrew ended the interview by asking about whether Buckley regularly wrote songs based on dreams, as Mojo Pin had been. “Dreaming, both waking and asleep, [is] a reservoir of mine. The thing is, there’s no difference for me between dream states and living. They both carry truth to them. I can read them both. I feel things in my dreams and I feel all the things that human beings’ lives bring them, except sometimes there are purple monsters or a chocolate dog trying to wake you up, but it’s still all very valid to me and I read situations in waking hours just like I read them in my sleeping hours, my sleeping hour, my lack of sleep world.”

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://tidal.com/magazine/article/jeff-buckley-lost-interview/1-85988

Jeff Buckley: The Lost Interview

In this previously unpublished conversation from 1994, captured just days before the release of ‘Grace,’ the mythic singer-songwriter pushes through self-doubt, professes his undying love for the Smiths and New York City, and interprets a dream wherein he critiqued a serial killer’s photography.

July 21, 2022 by Tony Gervino

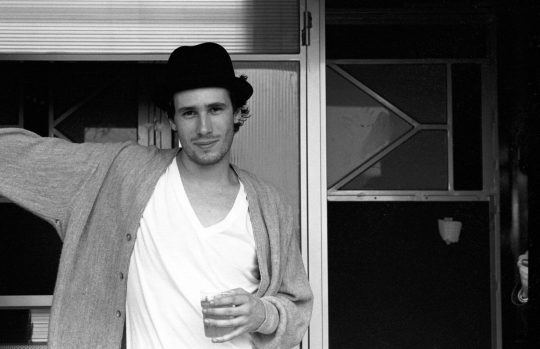

Q: Who and what are you going to become, Jeff? A: I don’t know, just something deeper: Buckley in 1994. Credit: Michel Linssen/Redferns.

In August of 1994, I interviewed the singer-songwriter Jeff Buckley for over an hour at the New York offices of Columbia Records. Other than pulling a few quotes for a regional music newspaper profile I wrote at the time, this conversation went unused. I put the recording in a box in my closet, where it remained for a quarter-century.

I went back over the transcript a couple of years ago and realized that our conversation offered a rare snapshot of the most pivotal moment in Buckley’s too-brief career. He hadn’t yet sat for many interviews and was trying to figure out his own narrative, just before he was to leave on a national tour that would make such quiet, thoughtful introspection a luxury.

The son of folk visionary Tim Buckley, he had made his mark in New York City as a solo artist in 1993, performing a suite of original songs and genre-spanning covers with only his guitar and multi-octave vocal range. The buzz didn’t really build; it seemed as if one day no one in the city’s music scene knew who Jeff Buckley was, and the next, everyone knew.

Prior to entering the studio to record his landmark debut album, Grace, which featured his most successful single, “Last Goodbye,” as well as his transcendent rendition of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah,” Buckley mothballed his troubadour set. To help bring dimension to the music swimming around in his head, he recruited the collaborative working band of guitarist Michael Tighe, bassist Mick Grondahl and drummer Matt Johnson. He wanted his solo album to sound big, ambitious and genre-slippery as he headed to Bearsville Studios in Woodstock, N.Y.

Even though our meeting was less than two weeks before the album release, Buckley was still tinkering with the mixes on Grace, tormenting producer Andy Wallace with sonic flourishes and rewritten bridges, and hoping to squeeze every bit of inspiration out of himself before the tape stopped rolling. In the pre-streaming world, this was an unheard-of high-wire act for a debut artist. But for a young musician who was signed to Columbia Records after a prolonged bidding war, it indicated a bit of acquiescence on the label’s part. From what they’d seen of him, Buckley was a can’t-miss artist. He just needed time, which, tragically, he was ultimately denied. Jeff Buckley drowned in Memphis in May of 1997, just 30 years old.

I’ve edited this interview for length and clarity and removed some passages where I thought Buckley’s sarcasm could be misinterpreted, or where it spun off into tangents that ended with Buckley impersonating everyone from Paul McCartney to the French poet Baudelaire. He had the nervous energy of someone about to embark on a long journey, uncertain of its destination, and I wanted to ensure his answers would properly reflect not just his wit but his wisdom.

*****

How does it feel to have to do interviews?

Well, at the outset I guess I figured why would anybody care? But I’m smart enough to know that people would want to talk about my music. I just didn’t think anyone would for a publication. But at this point the fatigue hasn’t set in, and no question is a stupid one.

It’s still early.

[laughs] Mainly it’s helpful because I’m getting some ideas out about exactly what I think about some things. And the important thing in doing interviews is not to have any pat answers. That would make it unenjoyable for me. Like a … a murder suspect or something, in terms of having your story straight.

Have you finished mixing the new album?

No, I have one last day in the studio — one last gasp of creative breath before I have to go away. I’m totally pissed. Absolutely.

Did you write in the studio, or did you go in with the songs ready?

One of them was completely organized in the studio. But that was still prepared beforehand. A lot of stuff we’d done at the last minute because I was trying to get the right people to play with, and it took a while before I found them.

But that was only three weeks before I’d gone up to Woodstock to record and we hadn’t known each other that long, and the band material hadn’t developed as much. Some things were completely crystallized, and some things needed care, and they got it. I’m still not satisfied.

Let’s see: I get to go into the studio on Wednesday, the day before I leave and the night after I perform at [defunct NYC club] Wetlands. So I have one, two, three, four, five precious days to [work on the music], along with all the other stuff I have to do. I have to shoot some pictures, possibly for the album cover. Then at night I’m free to get these ideas together, and I’ll still have one last shot on two songs in particular. The producer [Andy Wallace] doesn’t even know what I want to do to this one song. [laughs] He’ll be horrified.

Have you played it out?

Uh-huh. There are just things I want to crystallize about it.

Is figuring songs out onstage a conscious effort on your part to fly or fail?

Yeah, because I love flying so much. But, really, it’s still a kind of discipline. I guess it’s an engagement. It’s not like having “song 1 to song 6 and then a talk.” I don’t know anybody who really does that. I know a lot of performers talk about not being so structured. … Sometimes you can see bands that have a set of songs, and that shit is dead. That … shit … is … dead.

When I perform, I’m working off rhythms that are happening all over the place, real or imagined, and it’s interactive. It’s got a lot of detail to it, so I can’t afford to tie it up in a noose, and put it in a costume that doesn’t belong on me. So yeah, it’s free but it has its own logic, and sometimes it completely falls flat on its face. But it’s worth the fall, sometimes. Because that’s life.

To me it makes sense to do things in that manner, because that’s really just the way life is when you step out of it and see that, like, your car has a flat and somebody smashed in your windshield and then, shit, you’re walking home and all of a sudden you run into somebody that turns out to be your favorite person for the rest of your life. It’s always … unfolding. You just have to recognize it, I guess. And that’s my philosophy, that I haven’t really thought about until you asked me.

Have you been a solo performer out of desire or necessity?

Both. I did it to earn money to pay rent in the place I was staying, and bills, and my horrible CD habit, and failing miserably all the time, always playing for tips and always just getting by — by the skin of my teeth.

To get this sound in order, you can have a path laid out in front of you, but if you don’t have the vehicle to go down the road you’ll never get to where you want to go. So I guess I was building the parts piece by piece or going through different forms, reforming them and trying out different ideas and songs.

How long have you been building these parts?

Some of them I wrote when I was 18 or 19, and some of them I wrote weeks ago, and some of them I’m still writing. [laughs] The rest of this album is kind of a purging, because the rest of the albums ain’t gonna happen like this. [points to chest] You’ll never see this person again.

Who and what are you going to become, Jeff?