#Kojima Kensaku

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Boxers of Yesterday Today and Tomorrow

Storytelling in Sports

A normal person otherwise devoid of any specific purpose finds their raison dêtre in training for the martial arts.

This single sentence storyline is a fundamental story type in many Asian stories. You find it in Chinese Shaolin Temple epics, Japanese and Chinese rival school epics, Thai action films, Spanish and French sword-fighting fictions, and even American dramas and comedies. Rocky is the most notable example of an American version of this story type. In every example, the storytelling rarely focuses on the action and instead puts the onus on the relationships the character has with the world.

The most notable Japanese examples are Samurai films and combat/sports manga. In most of these examples the protagonist is relatively normal, allowing the audience to relate to them. Then the narrative introduces a reason for the character to evolve during exposition. The main character then is introduced to a mentor, not unlike Joseph Cambell’s example path of the Hero’s Journey. In sports narratives this mentor is usually in the form of a coach or trainer and they are uplifted from normal person to a superior athlete.

In sports manga and other sports fiction, the answer to all problems is always the same: Training.

Discipline provides confidence and training provides strength. Both of these are held together with ‘guts’ or determination. The athletic hero is confronted with stronger and stronger opponents and continues to train until he can defeat them. This type of ‘superiority through training and determination’ is a cornerstone of most Japanese stories. Many deal with an argument between skill and talent as well. In most cases learned skill defeats natural-born talent after enough training has occurred.

The lessons taught in these stories are almost always the same:

Nothing good is achieved without effort

Trust your friends and family

Strength is the product of discipline

Determination will give you victory

In this essay I will be focusing on three Boxing stories from Japanese culture. We will explore their meanings and narratives, the lessons taught, and the importance of their stories on culture.

Joe Learns to Box: Yesterday’s Tomorrow

Pugilism has a long history of nobility and violence. Boxing is enjoyed the world over as the world’s most basic of martial arts. Everyone can do it, but few can master it. Despite the sport’s organization being mostly from a European base, the United States has become the de facto home of the sport. It spread across the world and entered Japan in 1854 and became popular despite Japan’s dominance in the martial arts world.

Post World War II anti-American sentiment led to a lull in the sport, but boxing matches continued. As Japanese classical art like Emakimono evolved into Manga, artists struggled for meaning in a post nuclear world. One particular author found this meaning in the story of a prize fighter from the slums of Tokyo. Asao Takamori under the pen name Ikki Kajiwara teamed up with the artist Tetsuya Chiba to create their seminal work, Ashita no Joe. The story captured the spirit of Japanese determination and also their desperation in the face of their defeat of WW II and the subsequent reconstruction period. Joe’s redemption and anger belonged to the youth of the day and inspired other authors, artists, and aspiring boxers to try their best to grow and learn what it means to be strong.

Using this story as a lens to view other anime and manga you can see its influence everywhere you look, from popular to obscure. Notably Takamori’s story inspired a renaissance of boxing fandom in the late 1970’s. Despite there being several titles going to Featherweight and Welterweight champions in Japan during the time, boxing was relatively unpopular due to its association with the US. Ashita no Joe, or “Tomorrow’s Joe” captured a moment and helped to move its fans forwards toward a brighter tomorrow.

The titular character Joe Yabuki, is a tough-as-nails drifter that wanders into a shantytown and runs into an alcoholic boxing trainer, who sees a bright future hiding inside the brash youth and attempts to coax it out of him. Because of his terrible attitude and criminal behavior he is instead put in jail. Joe redeems himself (somewhat at least) and pushes himself to become a professional boxer. His story can be seen as a successful transition from an economic outcast into a functional member of society. In this case, society can be said to be the true villain of the story. Joe has either rejected society or society has rejected him, he has either turned to violence or been rejected due to his reliance on violence to solve his problems. Similar story origins can be found in gangster movies but also in stories like Rambo: Firstblood.

Classic and contemporary gangster films have characters that as children are shown a violent way of life, either by design or necessity. These children then grow into violent adults, full of anger and contempt for society and view the world as a thing to be possessed or conquered. Society ultimately rejects them for their violent and destructive natures. Stories like Rambo on the other hand, have a well liked child grow into a life of violence for a noble cause, but are ultimately unable to separate this violence from their personality. They eventually reject society as they cannot find a place and the violence in them serves no purpose.

Yabuki is a bit of a mystery as we have no context to put him in, but as with both other character types, his violence serves no purpose. He is defined by his violence and it colors all of his actions towards others. Joe is a fundamentally unlikable character, full of anger, bitterness, and child-like pettiness. His relationship with those that eventually come to care about him serves to instill societal norms in him in an attempt to turn him into a better person.

Instead of society itself, I propose that poverty is the real enemy of Joe and his friends. Every day is a struggle for all of them in San’ya. Economic disparity is on parade throughout the narrative, from the driftwood houses along the Namida Bashi (Bridge of Tears) to the sky scrapers and mansions of the mega-wealthy. Joe is carted around the world boxing in various countries, but he never really grows out of the slums in his mind. Joe is obviously a victim of his own stubbornness, but he was made that way because of lack of economic opportunity. This is one of the primary stumbling blocks on display in gangster stories, but instead of becoming an enforcer and earning a living in the underworld, Joe becomes a homeless wanderer, evoking the Japanese concept of a Ronin. A skilled fighter, disgraced and masterless but clinging on to his own moral code as he wanders from town to town.

While Joe is a product of his time, his story is no less poignant for modern audiences. I enjoy Ashita no Joe for a variety of reasons, but one of the best is its lack of focus on form. Chiba’s art is almost romantic with emphasis on Joe’s inability to care about the world, and Takamori’s rambling narrative is like a daydream at times with no obvious focus or form. If I had to compare it to music, Joe’s story is like a free form jazz with some repeating phrases and a theme, but mostly feels disorganized and yet is familiar. Joe has emblazoned himself into the minds and hearts of Japanese artists and athletes for decades and will continue to guide hearts, minds, and fists for decades to come.

Ippo Steps into the Ring: Yesterday’s Today

In sharp contrast to the unlikable character study of Joe Yabuki, we now come to possibly the most likable character in all of Japanese sports manga. Makunouchi Ippo, the titular character of Hajime no Ippo, has a boundless optimism that is almost never extinguished and his ability to win through sheer will power is incredibly inspirational. When I meet people that do not watch any anime or read manga and they ask me what to start with, Ippo’s story is always close to the top of the list. Of the three stories explored in this work, Ippo is my favorite. I have watched Ippo's road to fight against Date Eji more times that I can remember.

As with Joe, Ippo is a product of his environment and time. He is an example of modern boxing theory and technique tempered with lessons from the past. The origins of boxing are represented by the retired boxers in the narrative and the techniques of famous modern era boxers are on display in this love letter to obscure boxing styles. Ippo is the son of a fishing boat captain whose good naturedness causes him to forgo friendships and childhood distractions to help his mother operate the fishing boat business that supports them after his father's death. He is bullied and taunted until a chance encounter with a professional boxer saves him from a group of wannabe hoodlums underneath a bridge. Ippo awakens to find himself in the world of boxing and puts all of his considerable determination into making himself a professional licensed boxer. He manages this and continues to help his mother without complaining or losing his intoxicating optimism.

Makunouchi is meant to be a representation of the perfect son in Japanese culture. He is mannered, self-effacing, and always does the right thing. Conceptually, Ippo is almost as far as possible from Joe as a character. The world that Ippo exists in is also just as opposed to Joe’s world. While economics do factor into the narrative a bit, it is not a focus of the story. In this world the common everyday experience of Japan’s average citizen is on display. The manga is in full swing with shonen style comedy and slice of life stories, Ippo’s life is beset with heartache, rivals, highschool life, and bad dating advice.

The thing that really sets Ippo apart is the illustration of effort and power in the art of the near constant boxing and sparring matches. Although the art is a bit dated, it still communicates emotion and drama in a way that no other sports show has ever done in my opinion. Some of the later fights continue to give me chills and despite knowing the outcome of every fight, I still find myself cheering on Ippo. The color palette for everyday life is somewhat subdued but still contains a range of colors, but the fights are incredibly bright with flashes and huge blast lines. Usually this style of art would be a turn off for me in other mediums, but somehow Hajime no Ippo gets away with it.

If Joe’s story is Jazz, then Ippo is a Rock Ballad. Guitars scream at times, but other times the story is whimsical or romantic. George Morikawa’s skillful blend of emotions bring you through a chord progression of inspiring notes building to larger than life crescendos, that crash down upon you in a hail of pummeling fists, and knock you out with the power solos that are the crowd pumping championship matches. The drama conveyed in Takamura’s face while he attempts to control himself from opening a refrigerator while dieting to make weight, and the joyful head nod that Ippo gives when he defeats the first villain of the show are highlights that play on an loop in my mind drenched in squealing guitar riffs and the roar of the crowd.

One of the craziest things about watching the show for me is the effect it has on my exercise habits. If I ever want to get motivated to work out, I put on the first season of Ippo. Just as Ashita no Joe’s world is meant to capture the desperation of the downtrodden and the realism of his world, Hajime no Ippo seems to look at the world through Ippo’s guileless naivete. Ippo’s world is both very realistic and simultaneously extremely exaggerated. This offputting juxtaposition is difficult to navigate at times when you are wondering what is real and what is imagination.

Junkyard Dog Bites Mankind: Today’s Tomorrow

When writing about the future one of the things you have to ask yourself is ‘what will X be like in the future?’ Yō Moriyama, Katsuhiko Manabe, and Kensaku Kojima asked themselves, what would boxing be like in the future? How would people fight in the age of machines and artificial intelligence? Gearless Joe is the answer, or rather the inverse of the answer as he is essentially an anti-hero forgoing the future methods of robotic-assisted carnage, for old fashioned human-powered beatdowns.

If Hajime no Ippo is Classic Rock and Ashita no Joe is Jazz, then Megalobox is Industrial HipHop. It is hard, but rhythmic, artistic and catchy. By far the most polished of the 3 examples, it is an extremely fun watch and is effectively a stylized re-telling of Ashita no Joe. The nameless protagonist chooses the moniker ‘Joe’ meaning a man with no real name, but also an obligatory hat-tip to the source material that inspired them. Originally self-named ‘Junk Dog’ is employed to fight in fixed matches in the underworld that our original Joe eschewed. He feels trapped by his life and while attempting to force change, ends up essentially trapping himself even worse. Through a twist of fate, he is forced into the world of professional legitimate boxing in which if he loses he will die. In this brutal and vicious dog-eat-dog world, Gearless Joe shines as a likable anti-hero.

Unlike Ashita no Joe, society is not the big bad guy. There are of course real bad guys in Megalobox in the form of gangsters and fixers and hustlers, but the true villain in the story is greed. The story paints a nasty picture of corruption in the slums and then opens up the world into the bright lights of the legitimate world. With every turn you see another sign of economic elitism, not the least of which is Joe’s lack of personal identity. He is a non-person in the society and cannot even be allowed into the city, there is of course a blackmarket answer for everything and Gearless is allowed to come into the futuristic world of the Megalonia tournament and fight for his life.

His trainer sets up their gym under a bridge bearing more than a passing likeness to the same Bridge of Tears from Ashita no Joe. His team and Gearless Joe are the only desperate ones in the narrative, so unlike the feeling of inclusivity that Yabuki’s gang felt, Gearless Joe feels isolated.

An Abridged Story of A Bridge: Tears to Cheers to Fears

Dieting and sweat, training and bruises, bright lights and cheering crowds. There are a lot of things that the stories share due to the sheer concept of boxing, but one thing that stands out the most to me about the similarities is the geography. Ashita no Joe and Hajime no Ippo canonically occur in Tokyo whereas Megalobox occurs in the fictional ‘Administrative Zone’, but a common point with all stories is their reliance on a single feature of the landscape, a bridge. The bridge in Ashita no Joe is a famous one called Namida Bashi or the Bridge of Tears. It got this name due to the requirement that future prisoners of Kozukahara penitentiary would have to say their goodbyes to their loved ones on that bridge as you had to cross the Omoigawa river to get to the prison. The river was moved and the bridge doesn’t exist anymore, but in its time it was a symbol of loss and heartache and of loss of agency. It was no small symbolism for Joe’s trainer Danpei to open his ramshackle gym under the bridge. Joe’s relatively brief stint in prison and their constant struggle for survival, coupled with Joe’s incessant need to cause trouble always lead to loss, heartache, and usually a loss of agency. Many of Ashita no Joe’s most important moments occur in and around the bridge, borrowing context from the bridge’s reputation. Each of these events is usually a precursor to a major event in the context of Joe Yabuki.

Even though the bridge is now gone, the area around the bridge’s location is close to the Tiato and Arakawa districts that have several rivers that run through them with modern bridges that look remarkably like the one that serves as a setting for many of the critical plot turns in Hajime no Ippo. We see the entire storyline of Ippo’s relationship with Umezawa (Ippo’s school bully that is turned into his greatest fan) unfold under and around the bridge. Ippo manages to catch the 10 leaves that teach him how to jab next to the bridge, and several key conversations and character introductions are in and around the canal next to the bridge. I don’t feel that this use of the canal next to this particular bridge is random and suspect that if it isn’t just an icon from the author’s youth, it is an homage to Ashita no Joe’s use of the Bridge of Tears.

Ippo’s story doesn’t revolve around the same themes, so the bridge being similar but different is important in my mind. Being under the bridge, where Joe and Danpei were, is when Ippo is at his weakest and most vulnerable. The wise tree nearby becomes his first teacher and Ippo learns that he can grow stronger through dedication and training. This causes the bridge to become a symbol for growth and hope for a better tomorrow for Ippo. Even Umezawa crosses the bridge on his way to become a better person. Like Ippo is the inverse of Joe, the bridge in Hajime no Ippo is the inverse of the Namida Bashi. Everytime a character crosses the bridge they are stronger than they were before.

Megalobox as a revamp of Ashita no Joe also has a bridge, and of course they have their ‘gym’ underneath it. The symbolism in Megalobox is missing however and the bridge takes on a different meaning. Joe Yabuki and his trainer Danpei are poor in a community of poor people and they have a community to help them make their gym a home. Gearless Joe and Gansaku Nanbu have no such community to help them and must toil essentially on their own. The bridge and the river are essentially signs of the reality of illegal squatting, evidence that they do not belong in the world they find themselves in. As Gearless Joe and Nanbu rock the boat in entirely different ways than Joe Yabuki, death at the hands of the corruption of the city is their motivating factor instead of prison and poverty. The bridge over their heads instead becomes a symbol of cover, of hiding in plain sight. Not unlike the nameless boxer’s decision to choose the anonymous name of ‘Joe’.

To my reckoning there are a lot of examples of symbolism in all three stories, but none are shared so visibly and with as great an impact as the bridges over the heads of heroes while they train and live life outside the ring. Plans are formed, strategies devised, and history is made under these bridges, while clueless people stroll above them not knowing what extreme determination and strength of will lies beneath.

#boxing#hajime no ippo#ippo makunouchi#ashita no joe#megalo box#anime#animation#stories#modern mythology#heroes journey#joseph campbell#joe yabuki#gearless joe#Danpei#Gansaku Nanbu#Yō Moriyama#Katsuhiko Manabe#Kensaku Kojima#Asao Takamori#Ikki Kajiwara#Tetsuya Chiba#manga#manga art

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

TMS Entertainment and actor Michael B. Jordan have announced that the Japanese theatrical release of the Creed III will feature a special anime by the director and writers of Megalobox at TMS Animation. The anime will play after the end of the film, which opens in Japan as Creed Kako no Gyakushū (Creed: Revenge from the Past) on May 26, 2023.

Yo Moriyama is directing the anime at TMS Entertainment. Katsuhiko Manabe and Kensaku Kojima are writing the script. The director and writers worked on both Megalobox and its sequel Megalobox 2: Nomad.

Hi Japan! We made a special anime as a surprise for Japanese fans that will play at the end of the film. Creed 3 opens in theaters in Japan next weekend - get your tickets now to see what it’s all about!

- Michael B. Jordan

#Creed III#Creed 3#Creed#Rocky#Michael B. Jordan#Florian Munteanu#Metro Goldwyn Mayer Pictures#Chartoff Winkler Productions#Balboa Productions#Proximity Media Outlier Society#TMS Entertainment#film#live action#live action film#anime#shorts#anime shorts

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Review 532: Tsugaru Lacquer Girl

Written By:

Kensaku Kojima, Miyuki Takamori, Keiko Tsuruoka

Directed By:

Keiko Tsuruoka

Presented By: Japan Society

@jsfilmnyc tinyurl.com/JS-Family-Flux-Tix

Ricky’s grandfather used to pour concrete. There wasn’t a driveway in their small town or a sidewalk at their university that didn’t have his fingerprints on it. He had intense pride in his work and he never left a job without making sure that it was perfect. It was that same look of serenity when he was doing a job that Ricky and Dana saw in the main characters of this film. The serenity of a job that brings you joy and connects you to a community.

Keiko Tsuruoka

This is a film that had a deep respect for the craft that it was showing, Tsugaru lacquer work. You could tell that Tsuruoka had taken the time to get to know every step in the process. She also wasn’t afraid to let the imagery take center stage. There are several sequences where we are watching the characters work without dialogue. Yet we can still feel the story through how they use a brush, how they watch each other work, or how tired they look when they finish a piece. The camera doesn’t skimp on these details just as they wouldn’t skimp on their craft.

We love that this is a love story between an artisan and her craft. The piano is a perfect expression of this love story. This is the instrument that her mother never let her learn to play and the art form that her father never thought that she would be able to master. The piano becomes an intersection of passion and her history. It’s her statement to the world that she will live her life by her own rules.

This is a film that relies heavily on location. The cramped environment of the workshop with her Dad Seishiro or the widespread yet desolate nature of the neighborhood. Each place feels closed off and Miyako feels like a visitor in her hometown. Sadly very many of us could say the same. We latch onto Miyako’s story because we all hope to one day find something that will fulfill us as much as her art did for her. All of us crave acceptance, expression, and a sense of belonging. Miyako’s story reminds us that sometimes we have to listen to that inner voice that tells us to keep trying even when the world doesn’t understand.

0 notes

Video

youtube

#Megalobox#Megalo Box#Moriyama You#Hosoya Yoshimasa#Manabe Katsuhiko#video#Kojima Kensaku#VTR#Megalobox PR

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anime NYC: TMS Entertainment Announces Megalo Box Sequel

Anime NYC: TMS Entertainment Announces #MegaloBox Sequel

Today at Anime NYC, TMS Entertainment announced that they are currently developing a sequel to their anime series Megalo Box. For those unaware, Megalo Box is an original story and production that commemorates the 50th anniversary of Ikki Kajiwara (Asao Takamori) and Tetsuya Chiba’s manga, Ashita no Joe. The series features, a man called JD (Junk Dog) who participates in underground boxing…

View On WordPress

#Adult Swim#Anime NYC#Asao Takamori#Ashita no Joe#Ikki Kajiwara#Katsuhiko Manabe#Kensaku Kojima#Mabanua#Megalo Box#Megalo Box Season 2#Megalo Box Sequel#Tetsuya Chiba#TMS Entertainment#Toonami#Viz Media#You Moriyama

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Megalo Box#Ashita no Joe#Asao Takamori#anime#gif#Yō Moriyama#Katsuhiko Manabe#Kensaku Kojima#TMS Entertainment

99 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Megalo Box Sequel Announced

https://wp.me/p4jiOt-cld

At the recent Anime NYC event, it was announced that the 2018 anime Megalo Box is receiving a sequel titled…

#2019#anime#anime announcement#announcement#Ashita no Joe#images#Katsuhiko Manabe#Kensaku Kojima#mabanua#Megalo Box#Megalo Box 2#original anime#promotional video#tms entertainment#TV anime#video#visual#You Moriyama#あしたのジョー#メガロボクス#メガロボクス 2

0 notes

Text

Anime News Networkにスタッフインタビューが掲載!

北米最大規模のアニメ紹介サイトAnime News Networkにスタッフインタビューが掲載されました!

ぜひチェックしてみてください!

https://www.animenewsnetwork.com/feature/2021-06-04/discussing-the-socio-politics-of-megalobox-2-nomad-with-you-moriyama-katsuhiko-manabe-and-kensaku-kojima/.173444

記事の日本語訳はこちらです↓↓

『Nomadメガロボクス2』は、メガロボクスの物語を驚くべき新しい方向へと進めました。 ジョーと勇利の運命的な試合から数年後、ジョーは地下ボクシングの試合で戦う放浪者となりました。 ANNは、この予想外の続編がどのようにして生まれたのかについて、監督の森山洋氏、脚本家の真辺克彦氏、そして小嶋健作氏にお話を聞きました。

Nomadインタビュー:『Nomadメガロボクス2』ライター陣、及び監督

『メガロボクス』の世界に戻ってきました。勝利以来、ジョーには多くの変化がありました。『あしたのジョー』では、ジョーの結末(最期)を曖昧に描いていましたが、『メガロボクス』のジョーは、死の可能性もありましたが切り抜けたようですね。それでも、苦労しています。ジョーの物語を新たな方向へ出発させることにした経緯についてお話しいただけますか?

【森山】:『メガロボクス』終了後は次回作となる別の企画を考えていたのですがなかなか思うように進まず、同時にプロデューサーから『メガロボクス』の続編を考えてみてはどうかと打診を受けました。前作のラストで物語としては区切りをつけたものの彼らキャラクターの人生があそこで終わったわけではない、勇利に勝利しメガロボクスの頂点に立ったことがジョーの人生の最も輝かしい瞬間であるならその後はどうなるのか。前作では描かなかったものをテーマに据えるのであれば続編をやる意味があるだろうとストーリーを考え始めました。

【真辺】:脚本家チーム含め、監督、プロデューサー全員が続編をつくることは全く考えていませんでした。別のオリジナル企画を進めていたのですが、なかなかうまくいかず、そんな時にメガロボクスが海外で高い評価を受けていることから続編をやらないかという話があり、もう一度向き合うことになりました。 ただ、全てやり切ったという空っぽの状態からのスタートだったので、どういう物語にするか? 様々なアイデアが出ましたが、これだという確信を持つまでには至りませんでした。打ち合わせが終わるといつも居酒屋で飲みながら話すのですが、そんな中で“許されざる者”になったジョーというキーワードが出ました。監督の森山氏がそれを元に今回のNOMADOのベースになるプロットを用意し、そこから自らの過ちで故郷と家族を失ったジョーの再生を核に物語を構築していきました。メガロボクスの頂点へ駆け上った奇跡の三ヶ月は通過点に過ぎない、生きている限り人生は続くのだという普遍的なテーマは私たち作り手にもフィードバックし、直面している現実や社会から目を背けることなく描こう、という共通認識が私たちに生まれました。その困惑と思考がNOMADOという物語にリアリティと熱量を持たせたのだと思います。

【小嶋】:『あしたのジョー』の結末で、ジョーは真っ白な灰のように燃え尽きました。『メガロボクス』のジョーは、リングの上で死ぬことはありませんでしたが、勇利との戦いを終え、ある意味で燃え尽きてしまったのだと思います。そんなジョーがもしもう一度リングに上がるとしたら何のためか? 続編をつくるにあたって、監督、プロデューサー、脚本チームで話し合いを重ねました。その中で森山監督から提示されたのが、チーム番外地にとって太陽のような存在であった南部の死と、罪を背負って地下を放浪するジョーというアイデアでした。あの輝かしい勝利のあとで、ジョーの身に何かが起き、すべてを失ってしまった。そのアイデアに強く魅了された私たちは、どこへどう辿り着くのかわからないまま、とにかくその方向へと物語を出発させることにしたのです。

本作品に登場する移民体験は、多くのファンの共感を呼んでいます。チーフと彼のコミュニティに関して言えば、本物らしく(リアリティをもって)見せるために、どのようにしましたか? 何か参照したものはありますか?

【森山】:『メガロボクス』の近未来世界には様々な国籍のキャラクターが登場することもあり、舞台の裏側のこととはいえ人種問題や移民問題は常に自分の近くにありました。それもあって続編にはその要素を物語に絡められたらと考えました。自分は移民問題についてのエキスパートではありませんが、ニュースやドキュメンタリーなどこれまで見てきたものからヒントを得て物語の構築や絵作りを行いました。個人的には映画の影響が強く、例えばケン・ローチ監督作品やスパイク・リー監督の『Do the right thing』は制作中に観返したりもしました。同じ場所で生きる様々な人間たちの複雑な関係性、表裏のある言葉のやり取りなどはチーフと仲間たち、彼らを排斥しようとする者たちの考えや行動に影響を与えていると思います。

【真辺】:私の住んでいる街では多くの外国人が暮らし、母国を離れざるを得なかった難民の方もいます。恥ずかしい話ですが、彼らに偏見を持ち、差別的な言動をする人間も存在します。 歴史を遡ると、多くの日本人がアメリカだけでなく、中南米に移民として海を渡りました。今の日本には日系ブラジル人や日系ペルー人の方々が各地で暮らし、カーサのようなコミュニティがつくられています。いわれなき差別を受け、満足な公共サービスを受けられない人々に対し、私も含め多くの日本人は労働の担い手としか見ようとせず、無関心を貫いてきました。既に二十年以上、この国で共に生きているにも関わらず、です。無知が恐れを生む悪循環を止めることは困難ですが、わずかでも抗うためのクサビを打ちたい、そんな思いをこの物語に込めました。共感を呼んでいるのだとすれば、その祈りが届いているのだと思います。私は悲観主義者なのですが、掲げた理想を現実に引きずりおろす愚かな真似はしたくないのです。

【小嶋】:私が住んでいる埼��県の蕨市という小さな町には、外国からの移住者が多く暮らしています。排外主義者のグループがヘイトスピーチをしに来たこともあります。特にクルド人住民の数は日本の中で一番多く、”ワラビスタン”とも呼ばれています。彼らは母国での迫害を逃れて日本にやって来た人たちとその家族ですが、政治的理由で難民申請を受理されないまま、人権を制限された状態で暮らしています。日常的に彼らの姿を目にしていることが、本作品での移民体験の描写に影響しているのかもしれません。 参照した作品を一つ挙げるとすれば、イギリス映画『THIS IS ENGLAND』です。ミオと地元の少年たちの関係を描く際に参照しました。

勝利した後、ジョーは、ある層の人々からヒーローとして受け入れられるわけですが、『メガロボクス』のジョーに、どういう男性像を見出しますか? また、ジョー(の生き様)が心に響くとすれば、どういうことを体現しているからだと思われますか?(ジョーという存在のどういうところが、心を打つのか…皆さんにとってどういう存在でしょうか)

【森山】:人種も何も関係のないひとりの人間の個の獲得、その強さや輝きというものがジョーというキャラクターの魅力なんだと思います。だからこそ助け合え、共に生きていけるという希望の象徴です。そこを描くことが前作のテーマであり課題でした。ジョーは男性ですがそこに性差は関係なく『メガロボクス』のキャラクターにはそういう思いを込めました。

【真辺】:『大きな力に対し、おもねるのではなく抗う』。名もなき存在であったジョーがメガロボクスの頂点に立ち、虐げられる立場の人々にとって希望の灯りとなった。チーフはまさにその象徴です。しかし、南部という父親を失ったジョーは、自らが父親の役目を果たそうとして家族であるサチオたちを傷つけてしまう。そのことは“男らしさ”という呪いの言葉に囚われた幼い自身の姿をさらけ出すことになりました。 家父長制とマチズモが賞賛される社会で生まれ育った人間にとって、この病を克服することは厄介です。かつてチーフもそうだったのかもしれません。ですが、チーフは家族を失いながらも成熟した“良き大人”の姿をこの物語の中で見せてくれました。ジョーもチーフのバトンを受け取ったことで、呪いから解放される姿を見せてくれるでしょう。 ジョーの魅力は、自分の弱さや不安を誰かを貶めることで解消しようとしない愚直な誠実さであり、優しさを失うことのない高潔さだと思います。そして冒頭に書いたように、権力や権威を嫌って、諦めずに抗い続ける強さ。私にとって彼は敬意を払うべき友人であり、「そんな風になりたい」と思う人間のロールモデルです。

【小嶋】:ジョーが体現しているものは“信じる力”だと思います。金でも、権力でも、神様でもなく、人を信じる力です。彼は“ギアレス”ジョーとしてチャンピオンになりましたが、心はずっと“ギアレス”のままです。相手に生身でぶつかっていくその無防備な誠実さと危うさが、見る人の心を打つのだと思います。

アニメやスポーツにとって、『あしたのジョー』の遺産は、どういうものだと思われますか?

【森山】:難しい質問でうまく答えられませんが……創作の場においては未だ影響の大きい作品です。

【真辺】:スポーツの面では、日本でスーパースターになった辰吉丈一郎というプロボクサーがいます。WBCのバンタム級チャンピオンでした。彼の丈一郎という名前は、彼の父親が主人公の矢吹丈から取ったものです。私も大好きなボクサーでした。 アニメの面では、特に『あしたのジョー2』については影響を受けていない作り手はいないと思います。技術面だけでなく、伝説の漫画原作に負けまいとせめぎ合う高い志に感銘を受けました。簡単に消費されないエバーグリーンな名作であり、未だに心を震わされます。

【小嶋】:『あしたのジョー』は、強烈なロマン主義と情念のリアリズムを併せ持つ偉大な物語です。その精神性は、アニメやスポーツに限らず、日本の文化に大きな影響を与えていると思います。しかし一方で、男らしさや、死の危険を顧みず命がけで戦うことを良しとする、いわゆる「男の美学」については、現代の価値観では受け入れ難いものがあることも確かです。それをどう乗り越えていくかが、今のクリエイターたちに与えられた課題だと思います。

視覚的に、メガロボクスは複数の点で特徴的です。その「粒子の粗い」外観にした背景には、どういう狙いがありますか?

【森山】:前作『メガロボクス』を制作中は原案である『あしたのジョー』とは距離を取りながら近づける、ということを意識していました。例えば、舞台だては大きく変えるが物語のテーマは引き継ぐというようなことです。「粒子の粗い外観」もその一つで、最新作を再放送のような画面で見るということがひとつ魅力になるんじゃないかと考えました。シンプルな構造の物語にはインパクトある画面が必要だったこともありますし、VHSのような劣化した画面が自分にとっては魅力的に映ることも大きいです。

森山監督は、コンセプトデザインの経験が豊富ですが、「ノマド」の世界を視覚化しようと思った出発点/インスピレーションは何でしたか? 監督ご自身が以前に関わった作品で得たスキルやアイデアで、メガロボクスの土台を築くのに役立ったものはありますか?

【森山】:インスピレーションはほとんどの場合これまで観てきた作品が深く影響していて、映画や音楽から得たものが特に大きいです。『NOMAD』制作中は特にアメリカやスペインの西部劇を観返すことが多かったです。他にもカメラワークなど昔ながらの方法で撮影された映像の雰囲気を取り��れたかったので60~70年代のニューシネマも良く観返しました。自分は実写の映像からアイデアを得ることが多いです。コンセプトデザインに取り組む方法は作品によって異なりますが、『メガロボクス』の場合は脚本チームとのミーティングも自分にとっては特に重要な要素です。会話の内容にかかわらずコミュニケーションのすべてが作品に影響していると思います。

真辺さんと小嶋さんは以前、実写のNetflixシリーズ『深夜食堂』でも一緒にお仕事されていますね。一緒に仕事をするようになったのはいつからですか。お二人の仕事上の関係はどのようなもので、ど��ように一緒に作業されるのでしょうか?

【真辺】:小嶋氏と共作するようになったのは、Netflixシリーズ『深夜食堂』からです。私が所属するシナリオ作家協会のシナリオ講座で講師をしていた時に、彼が講座生として来たのが出会いです。カリキュラムで2時間の映画脚本を書くのですが、彼は福島の原発事故をテーマにした話を書きたいと言ってきました。「センシティブな題材なので簡単じゃない」と私はアドバイスしましたが、「これを書かないと前に進めない」と彼は言い、取材をして書き上げました。そのことで「信頼できる書き手になるだろう」と思い、深夜食堂の監督である松岡氏に紹介しました。そして松岡氏の信頼も勝ち取り、脚本家チームに加わることになったのです。 出会いこそ講師と講座生ですが、シネフィルで映画の知識が豊富にある彼のアイデアは刺激があり、上下関係なく優秀な一人の脚本家として敬意を持って仕事をしています。 互いの家でアイデア二割、無駄話八割をしながらプロットを考え、脚本まで仕上げていくスタイルです。多少どちらかが先行するケースもありますが、プロットの段階で互いの意見を遠慮せずに言い合うことで、船を間違った方角に進ませる悲劇は起こりません。もちろん納得出来ないこともありますが、言葉を惜しまず耳を傾ければ、相手の意図が「この作品にとってプラスになるか、そうでないか」を判断出来ます。 脚本家にとって最も重要なことは、設計図であり楽譜でもある脚本をどれだけ強靭なものに仕立てられるかが作品作りのトップランナーとしての役目だと考えています。たまに私が先輩風を吹かすこともありますが、小嶋氏は寛容な心で受け入れてくれます。恐ろしくて本人には確かめられませんが。

【小嶋】:出会ったのは2012年です。真辺さんは私が通っていたシナリオ学校の講師でした。卒業後、真辺さんに誘われて、『深夜食堂』のプロジェクトに参加することになりました。以降、一緒に仕事をしています。 真辺さんとの作業はいつも、たくさん話しをすることから始まります。見た映画やドラマ、読んだ本、身の回りの出来事や世の中で起きているニュースなど、その時々の関心事についての会話の中から、アイデアが生まれ、少しずつ物語の形が見えてきます。仕事を忘れて、お喋りだけで一日が終わることも珍しくありません。そんな日は二人とも罪悪感に苛まれます。とにかく、そうやって書いたものを互いに読みあい、率直な意見を交わしながら、ブラッシュアップしていきます。 私は理屈っぽく観念的に考えてしまう癖があるので、真辺さんの直感的で具体的なアドバイスに、いつも助けられています。

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

MEGALOBOX 2: NOMAD premieres today

MEGALOBOX 2: NOMAD, the new TV series from Yō Moriyama, Katsuhiko Manabe, and Kensaku Kojima, is out today.

Years after his victory at Megalonia, Joe has become a completely different man, going from one underground ring to another, now fighting as the wandering boxer Nomad.

1 note

·

View note

Video

I watched an amazing anime called Megalobox by Katsuhiko Manabe Kensaku Kojima In the last episode the narrator said this and I thought it was brilliant and true. "Whether you wield the reins of power beneath a weighty crown or are the most destitute of paupers, no man escapes death. But if you live life so that when it comes you're satisfied even if it's not the end you hoped for, you'll have no cause to fear mortality" #megalobox #meaningoflife #value #mindfullife #mindfulquote https://www.instagram.com/p/Ce05BmaDpcm/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Video

youtube

Megalo Box 2: Nomad PV2. It’ll premiere on April 4, 2021.

Key visual

Cast additions

Atsushi Miyauchi as Mac

Chikahiro Kobayashi as Sakuma

Miou Tanaka as Chief

Farahnaz Nikray as Marla

Yumi Hino as Mio

Masaya Fukunishi as Ryū

Returning cast members

Yoshimasa Hosoya as Joe / Nomad

Shiro Saito as Gansaku Nanbu

Michiyo Murase as Sachio

Hiroki Yasumoto as Yuri

Nanako Mori as Yukiko Shirato

Tatsuhisa Suzuki as Mikio Shirato

Makoto Tamura as Tatsumi Leonard Aragaki

Staff

Director / Concept Designer: You Moriyama

Scenario: Katsuhiko Manabe, Kensaku Kojima

Character Designer: Ayumi Kurashima

Sub Character Designer: Naomi Kaneda

Music: mabanua

Animation production: TMS Entertainment

#Megalo Box 2#Megalo Box 2 Nomad#Megalo Box#Ashita no Joe#TMS Entertainment#anime#TV anime#long post

497 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Megalo Box TV anime promo featuring rapper COMA-CHI. A new key visual also appears on the official website. Broadcast premiere April 2018 (TMS Entertainment)

-Synopsis-

“Ashita no Joe 50th anniversary project.

JD (Junk Dog) participates in fixed boxing matches in an underground ring in order to live. Today, he enters the ring again, but he encounters a certain person. JD wants to take on a challenge that risks everything.”

-Staff-

Director: You Moriyama

Concept Design: You Moriyama

Series Composition: Katsuhiko Manabe, Kensaku Kojima

Music: mabanua

Animation Production: TMS Entertainment

-Cast-

Junk Dog - (CV: Yoshimasa Hosoya)

Gansatsu Nanbu - (CV: Shirou Saitou)

Yukiko Shirato - (CV: Nanako Mori)

Sachio - (CV: Michiyo Murase)

Fujimaki - (CV: Hiroyuki Kinoshita)

Yuri - (CV: Hiroki Yasumoto)

Source: http://megalobox.com/

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

TMS Entertainment Announces MEGALOBOX 2: Nomad Anime For April 2021

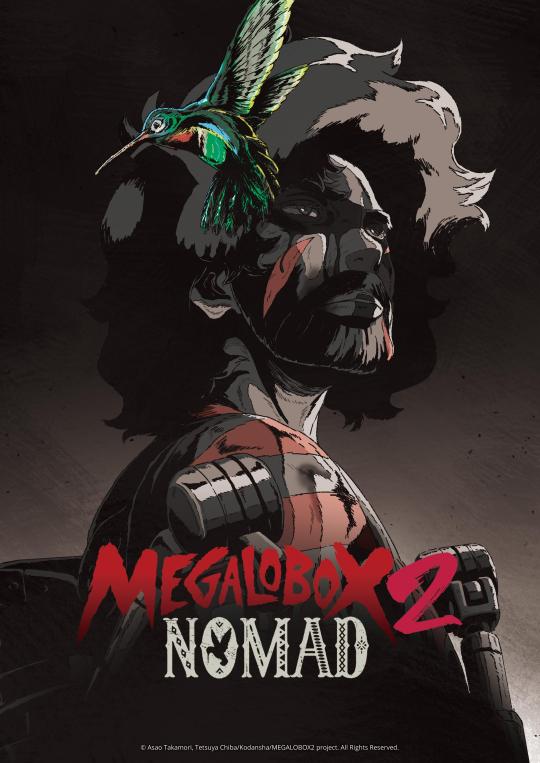

Anime studio TMS Entertainment has announced the long-awaited sequel to the 2018 hit boxing anime MEGALOBOX in MEGALOBOX 2: NOMAD. The anime will premiere in April on Japanese TV, with the studio also unveiling the first teaser trailer and key art, found below with English subtitles:

Trailer:

youtube

The key art is illustrated by the sequel's director Yo Moriyama and depicts a drastically different Joe to when we last saw him at the end of the first season, which foreshadows a much bleaker tone for the series:

Cast:

Joe / NOMAD: Yoshimasa Hosoya GANSAKU NANBU: Shiro Saito YURI: Hiroki Yasumoto SACHIO: Michiyo Murase

Staff:

Original Concept: Tomorrow’s Joe Original Comic Books Created by Asao Takamori, Tetsuya Chiba / Published by Kodansha. Director / Concept Designer: Yo Moriyama Scenario: Katsuhiko Manabe, Kensaku Kojima Character Designer: Ayumi Kurashima Sub Character Designer: Naomi Kaneda Music: mabanua Animation production: TMS Entertainment Co., Ltd. Produced by MEGALOBOX2 Project

Synopsis:

In the end, “Gearless” Joe was the one that reigned as the champion of Megalonia, a first ever megalobox tournament. Fans everywhere were mesmerized by the meteoric rise of Joe who sprung out from the deepest underground ring to the top in mere three months and without the use of gear. Seven years later, “Gearless” Joe was once again fighting in underground matches. Adorned with scars and once again donning his gear, but now known only as Nomad…

SOURCE: TMS Entertainment PR (English)

By: Humberto Saabedra

0 notes