#Klamath River basin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Excerpt from this story from Oregon Public Broadcasting:

At a small dam on Sun Creek made out of corrugated vinyl sheeting, National Park Service fish biologist Dave Hering shuts off water leading into a metal box the size of a small elevator.

Michael Scheu, one of Hering’s team members, climbs inside. Surrounding his feet are twelve bull trout. They got trapped here trying to head upstream. Scheu collects half of them in a black bucket, handing it off to another team member above.

Bull trout are the only remaining native fish species in Crater Lake National Park. They used to be found all over the Klamath Basin, Hering says, including nearby Fort Creek.

“Fort Creek is a place where a bull trout was sampled in the 19th century and actually held in the Smithsonian,” says Hering. “And for decades, including the whole first 15 years of my career here, we didn’t have bull trout there anymore.”

Competition from a closely related cousin, the brook trout, introduced for fishing in the early 1900s, was the primary factor leading to bull trout being listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 1998.

Native to the eastern U.S., brook trout evolved with slightly different traits that allow them to outcompete the bull trout in its natural habitat. They mature at a younger age, thereby producing more eggs over a longer period of time than bull trout, among other advantages.

In 1989, scientists found a disturbingly small number of bull trout high up Sun Creek, inside the national park. Mark Buktenica is the now-retired fish biologist for the park service who began the effort to save the species.

“The National Park Service mandate from Congress is pretty clear,” Buktenica said on a 1999 episode of Oregon Field Guide. “We’re supposed to preserve and protect these ecosystems in their natural condition. Well, the natural condition for Sun Creek is to have resident bull trout.”

Back then, Buktenica and his team built two dams on Sun Creek to prevent non-native fish from getting further upstream. Then, they used a specialized poison to kill any brook trout upstream of the dams.

Hering took over Buktenica’s work when he retired in 2017. He says he’s gotten more and more invested since their population has grown in number.

“A lot of people — anglers and fish enthusiasts — describe it as sort of an ugly fish or one that isn’t as nice to look at as some others. But I think they’re beautiful,” Hering says.

Hering was there when, in 2017, scientists reconnected Sun Creek to the Wood River for the first time in over 150 years. The tributary had been isolated on private land and used for irrigation, cutting bull trout off from other parts of the Klamath Basin.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Official nature post

Hey, don't cry. First salmon spotted returning to sites on the Klamath River previously dammed for more than a century, okay?

https://www.sfchronicle.com/california/article/klamath-dam-removal-salmon-19844792.php

14K notes

·

View notes

Text

"For years, California was slated to undertake the world’s largest dam removal project in order to free the Klamath River to flow as it had done for thousands of years.

Now, as the project nears completion, imagery is percolating out of Klamath showing the waterway’s dramatic transformation, and they are breathtaking to behold.

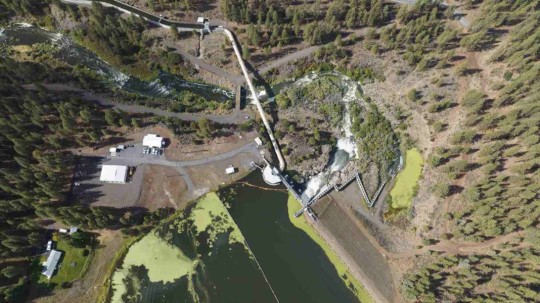

Pictured: Klamath River flows freely, after Copco-2 dam was removed in California.

Incredibly, the project has been nearly completed on schedule and under budget, and recently concluded with the removal of two dams, Iron Gate and Copco 1. Small “cofferdams” which helped divert water for the main dams’ construction, still need to be removed.

The river, along which salmon and trout had migrated and bred for centuries, can flow freely between Lake Ewauna in Klamath Falls, Oregon, to the Pacific Ocean for the first time since the dams were constructed between 1903 and 1962.

“This is a monumental achievement—not just for the Klamath River but for our entire state, nation, and planet,” Governor Gavin Newsom said in a statement. “By taking down these outdated dams, we are giving salmon and other species a chance to thrive once again, while also restoring an essential lifeline for tribal communities who have long depended on the health of the river.”

“We had a really incredible moment to share with tribes as we watched the final cofferdams be broken,” Ren Brownell, Klamath River Renewal Corp. public information officer, told SFGATE. “So we’ve officially returned the river to its historic channel at all the dam sites. But the work continues.”

Pictured: Iron Gate Dam, before and after.

“The dams that have divided the basin are now gone and the river is free,” Frankie Myers, vice chairman of the Yurok Tribe, said in a tribal news release from late August. “Our sacred duty to our children, our ancestors, and for ourselves, is to take care of the river, and today’s events represent a fulfillment of that obligation.”

The Yurok Tribe has lived along the Klamath River forever, and it was they who led the decades-long campaign to dismantle the dams.

At first the water was turbid, brown, murky, and filled with dead algae—discharges from riverside sediment deposits and reservoir drainage. However, Brownell said the water quality will improve over a short time span as the river normalizes.

“I think in September, we may have some Chinook salmon and steelhead moseying upstream and checking things out for the first time in over 60 years,” said Bob Pagliuco, a marine habitat resource specialist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in July.

Pictured: JC Boyle Dam, before and after.

“Based on what I’ve seen and what I know these fish can do, I think they will start occupying these habitats immediately. There won’t be any great numbers at first, but within several generations—10 to 15 years—new populations will be established.”

Ironically, a news release from the NOAA states that the simplification of the Klamath River by way of the dams actually made it harder for salmon and steelhead to survive and adapt to climate change.

“When you simplify the habitat as we did with the dams, salmon can’t express the full range of their life-history diversity,” said NOAA Research Fisheries Biologist Tommy Williams.

“The Klamath watershed is very prone to disturbance. The environment throughout the historical range of Pacific salmon and steelhead is very dynamic. We have fires, floods, earthquakes, you name it. These fish not only deal with it well, it’s required for their survival by allowing the expression of the full range of their diversity. It challenges them. Through this, they develop this capacity to deal with environmental changes.”

-via Good News Network, October 9, 2024

#california#oregon#klamath river#dam#dam removal#yurok#first nations#indigenous activism#rivers#wildlife#biodiversity#salmon#rewilding#nature photography#ecosystems#good news#hope

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Only four months after dams blocking migration were removed, the first Chinook salmon traveled 230 miles to return to the Klamath River Basin. This was the first fish to come home to their ancestral migration routes since 1912.

Over 100 years shut out and it only took them four months to return home once they had the chance.

From the article:

“The return of our relatives the c’iyaal’s is overwhelming for our tribe. This is what our members worked for and believed in for so many decades,” said Roberta Frost, Klamath Tribes Secretary. “I want to honor that work and thank them for their persistence in the face of what felt like an unmovable obstacle. The salmon are just like our tribal people, and they know where home is and returned as soon as they were able[.]"

#hope#good news#dam removal#salmon conservation#river conservation#indigenous conservation#endangered species#environment#biodiversity#hopepunk#chinook salmon#salmon migration#habitat restoration

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

In early October, the first time in 100 years, salmon were observed swimming past the sites of former dams as they migrated from the ocean into the Klamath River. This was made possible by the removal of dams that previously blocked salmon from completing their historic migration.

Interested in learning more? Join the California History Section for their next Speaker Series virtual talk, Toward a Decolonial Future: Klamath River Temporary Dams with Dr. Brittani Orona on Wednesday, November 13 at 4PM. With the four dams removed, this talk will explore the relationship of the lower Klamath River and how Hupa, Yurok, and Karuk story and ceremony intertwine on the Basin to build a new, decolonial future for the river itself.

The event is free but requires registration. For more information and to register, visit https://libraryca.libcal.com/calendar/californiastatelibrary/KlamathRiver .

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Can you imagine how many have been trying all this time?

🏞️ !!! happy breaking news !!! after more than 100 years, fall-run Chinook salmon have returned to the Klamath River Basin: one month after the last dam obstacle was removed!!! 🏞️ Mark Hereford, ODFW’s Klamath Fisheries Reintroduction Project Leader, was part of the survey team that identified the fall-run Chinook. His team was ecstatic when they saw the first salmon.

“We saw a large fish the day before rise to surface in the Klamath River, but we only saw a dorsal fin,” said Hereford. “I thought, was that a salmon or maybe it was a very large rainbow trout?” Once the team returned on Oct. 16 and 17, they were able to confirm that salmon were in the tributary.

It marks the return of migrating fish to the area following the removal of four Klamath River dams. The salmon likely traveled 230 miles from the Pacific Ocean.

49 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Weather: Pacific Northwest

Report generated at 2024-12-25 16:00:10.377378-08:00 using satellite imagery and alert data provided by the National Weather Service.

Winter Storm Warning

WA:

Central Chelan County

Lower Slopes of the Eastern Washington Cascades Crest

Okanogan Highlands

Okanogan Valley

Olympics

Upper Slopes of the Eastern Washington Cascades Crest

Waterville Plateau

Wenatchee Area

West Slopes North Cascades and Passes

West Slopes North Central Cascades and Passes

West Slopes South Central Cascades and Passes

Western Chelan County

Western Okanogan County

ID:

Bear River Range

Big Hole Mountains

Big Lost Highlands/Copper Basin

Blackfoot Mountains

Caribou Range

Centennial Mountains/Island Park

Franklin/Eastern Oneida Region

Marsh and Arbon Highlands

Raft River Region

Sawtooth/Stanley Basin

Southern Hills/Albion Mountains

Sun Valley Region

Teton Valley

Wood River Foothills

Winter Weather Advisory

WA:

Cascades of Lane County

Cascades of Marion and Linn Counties

North Oregon Cascades

Northeast Mountains

Northern Blue Mountains of Oregon

Northwest Blue Mountains

South Washington Cascades

Upper Columbia Basin

OR:

Baker County

Cascades of Lane County

Cascades of Marion and Linn Counties

East Slopes of the Oregon Cascades

North Central and Southeast Siskiyou County

North Oregon Cascades

Northern Blue Mountains of Oregon

Northwest Blue Mountains

Siskiyou Mountains and Southern Oregon Cascades

South Central Oregon Cascades

South Central Siskiyou County

South Washington Cascades

Upper Weiser River

Western Siskiyou County

ID:

Arco/Mud Lake Desert

Baker County

Bear Lake Valley

Beaverhead/Lemhi Highlands

Boise Mountains

Camas Prairie

Central Panhandle Mountains

Eastern Magic Valley

Frank Church Wilderness

Lost River Range

Lower Snake River Plain

Northern Clearwater Mountains

Northern Panhandle

Shoshone/Lava Beds

Southern Clearwater Mountains

Upper Snake River Plain

Upper Treasure Valley

Upper Weiser River

West Central Mountains

Western Magic Valley

CA:

Greater Lake Tahoe Area

Lassen-Eastern Plumas-Eastern Sierra Counties

Mono

North Central and Southeast Siskiyou County

Northern Trinity

Siskiyou Mountains and Southern Oregon Cascades

South Central Oregon Cascades

South Central Siskiyou County

West Slope Northern Sierra Nevada

Western Plumas County/Lassen Park

Western Siskiyou County

NV:

Greater Lake Tahoe Area

Northern Elko County

Ruby Mountains and East Humboldt Range

South Central Elko County

Southwest Elko County

Coastal Flood Warning

WA:

Central Coast

Coastal Flood Advisory

WA:

Eastern Strait of Juan de Fuca

North Coast

South Washington Coast

Western Strait of Juan De Fuca

High Surf Advisory

WA:

Central Coast

North Coast

South Washington Coast

OR:

Central Coast of Oregon

Clatsop County Coast

Tillamook County Coast

CA:

Catalina and Santa Barbara Islands

Coastal Del Norte

Coastal North Bay Including Point Reyes National Seashore

Los Angeles County Beaches

Malibu Coast

Mendocino Coast

Northern Humboldt Coast

Northern Monterey Bay

San Diego County Coastal Areas

San Francisco

San Francisco Peninsula Coast

San Luis Obispo County Beaches

Santa Barbara County Central Coast Beaches

Santa Barbara County Southeastern Coast

Santa Barbara County Southwestern Coast

Southern Monterey Bay and Big Sur Coast

Southwestern Humboldt

Ventura County Beaches

High Wind Warning

WA:

Admiralty Inlet Area

Central Coast

Clatsop County Coast

North Coast

San Juan County

South Washington Coast

Western Skagit County

Western Whatcom County

Willapa Hills

OR:

Central Coast of Oregon

Central and Eastern Lake County

Clatsop County Coast

Curry County Coast

Modoc County

Northern and Eastern Klamath County and Western Lake County

South Central Oregon Coast

South Washington Coast

Tillamook County Coast

ID:

Orofino/Grangeville Region

CA:

Central and Eastern Lake County

Coastal Del Norte

Modoc County

Northern and Eastern Klamath County and Western Lake County

Wind Advisory

WA:

Admiralty Inlet Area

Bellevue and Vicinity

Bremerton and Vicinity

Central Panhandle Mountains

Coeur d'Alene Area

East Puget Sound Lowlands

Everett and Vicinity

Foothills of the Blue Mountains of Washington

Foothills of the Northern Blue Mountains of Oregon

Hood Canal Area

Idaho Palouse

Lower Chehalis Valley Area

Lower Garfield and Asotin Counties

San Juan County

Seattle and Vicinity

Southwest Interior

Spokane Area

Tacoma Area

Upper Columbia Basin

Washington Palouse

Western Skagit County

Western Whatcom County

OR:

Central Oregon

Eastern Curry County and Josephine County

Foothills of the Blue Mountains of Washington

Foothills of the Northern Blue Mountains of Oregon

Foothills of the Southern Blue Mountains of Oregon

Grande Ronde Valley

Jackson County

North Central Oregon

ID:

Central Panhandle Mountains

Coeur d'Alene Area

Idaho Palouse

Lewis and Southern Nez Perce Counties

Spokane Area

Washington Palouse

CA:

Central Siskiyou County

Del Norte Interior

Greater Reno-Carson City-Minden Area

Interstate 5 Corridor

Northern Humboldt Coast

Northern Humboldt Interior

Northern Ventura County Mountains

Northern Washoe County

Santa Barbara County Interior Mountains

Santa Barbara County Southwestern Coast

Santa Ynez Mountains Eastern Range

Santa Ynez Mountains Western Range

Southern Humboldt Interior

Southern Ventura County Mountains

Southwestern Humboldt

Surprise Valley California

NV:

Greater Reno-Carson City-Minden Area

Northern Washoe County

Surprise Valley California

Hydrologic Outlook

WA:

Grays Harbor

Flood Watch

WA:

Clallam

Flood Warning

WA:

Mason

High Surf Warning

OR:

Curry County Coast

South Central Oregon Coast

Lake Wind Advisory

NV:

Western Nevada Basin and Range including Pyramid Lake

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The tribes, environmentalists and their allies celebrated the shrinking waters as an essential next step in what they say will be a decades-long process of restoring one of the West's largest salmon fisheries and a region the size of West Virginia back to health. Yurok tribal member and fisheries director Barry McCovey was amazed at how fast the river and the lands surrounding the Copco dam were revealed. "The river had already found its path and reclaimed its original riverbed, which is pretty amazing to see," he said. The 6,500-member tribe's lands span the Klamath's final 44 miles to the Pacific Ocean, and the Yurok and other tribes that depend on the Klamath for subsistence and cultural activities have long advocated for the dams' removal and for ecological restoration. Amid the largest-ever dam removal in the U.S., rumors and misunderstandings have spread through social media, in grange halls and in local establishments. In the meantime, public agencies and private firms race to correct misinformation by providing facts and real data on how the Klamath is recovering from what one official called "major heart surgery." But while dam removal continues, a coalition of tribes, upper Klamath Basin farmers, and the Biden administration have struck a new deal to restore the Klamath Basin and improve water supplies for birds, fish and farmers alike. ...

The Yurok Tribe also contracted with Resource Environmental Solutions to collect the billions of seeds from native plants needed to restore the denuded lands revealed when the waters subsided. The company, known to locals as RES, took a whole-ecological approach while planning the project. In addition to rehabbing about 2,200 acres of land exposed after the four shallow reservoirs finish draining, "we have obligations for a number of species, including eagles and Western pond turtles," said David Coffman, RES' Northern California and Southern Oregon director. ... The company also plans to support important pollinators like native bumblebees and monarch butterflies and protect species of special concern like the willow flycatcher. And, Coffman said, removal of invasive plant species like star thistle is also underway. In some cases, he said, workers will pull any invasives out by hand if they notice them encroaching on newly planted areas. ...

The Interior Department announced Wednesday that the agency had signed a deal with the Yurok, Karuk and Klamath Tribes and the Klamath Basin Water Users Association to collaborate on Klamath Basin restoration and improving water reliability for the Klamath Project, a federal irrigation and agricultural project. An Interior Department spokesperson said the agency had been meeting with river tribes and the farmers of the Upper Basin for the first time in a decade to develop a plan to restore basin health, support fish and wildlife in the region, and support agriculture in the Upper Basin. "We're trying to make it as healthy as possible and restore things like wetlands, natural stream channels and forested watershed," the spokesperson said. He likened it to keeping the "sponge" wetlands provide to store water wet. The effort is meant to be a cross-agency and cross-state process. The Biden administration also announced $72 million in funding for ecosystem restoration and agricultural infrastructure modernization throughout the Klamath Basin from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from this press release from the US Fish & Wildlife Service:

The U.S. Department of the Interior and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service today announced nearly $46 million in investments from President Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law for ecosystem restoration activities that address high-priority Klamath Basin water-related challenges in southern Oregon and northern California.

In February, the Department announced a landmark agreement between the Klamath Tribes, Yurok Tribe, Karuk Tribe and Klamath Water Users Association to advance collaborative efforts to restore the Klamath Basin ecosystem and improve water supply reliability for Klamath Project agriculture. Funds announced today will support 24 restoration projects developed by signers of this agreement, as well as other Tribes and other conservation partners.

Through President Biden’s Investing in America agenda, the Department is implementing more than $2 billion in investments to restore the nation’s lands and waters. To guide these historic investments, and in support of the President’s America the Beautiful initiative,the Department unveiled the Restoration and Resilience Framework, to support coordination across agency programs and drive transformational outcomes, including a commitment to advance collaborative efforts to restore the Klamath Basin ecosystem and improve water supply reliability for Klamath Project agriculture through the Klamath Keystone Initiative. By working collaboratively with ranchers, state and local governments, Tribal nations, and other stakeholders, the Department is working to build ecological resilience in core habitats and make landscape-scale restoration investments across this important ecosystem.

Through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law , the Service is investing a total of $162 million over five years to restore the Klamath region’s ecosystem and repair local economies. These investments will secure reliable water for the national wildlife refuges, advance the restoration of salmon post dam removal, address water quality and conveyance issues, and support co-developed restoration projects with Tribes, farmers and ranchers, and conservation partners.

As part of today’s investments, $13 million will be used to complete restoration of the Agency-Barnes wetland units of Upper Klamath National Wildlife Refuge and provide fish habitat access in Fourmile and Sevenmile creeks. Covering 14,356 acres, the restored wetland will create vital habitat for waterfowl, federally endangered Lost River and shortnose suckers, and other species, making it one of the largest wetland restoration initiatives in the United States.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A couple highlights:

There are now ZERO COAL POWER PLANTS in the UK. Zero! Also zero in Slovakia, which closed its last coal plant a full SIX YEARS ahead of schedule! This is great because coal is like, the dirtiest fuel source ever. It's awful for the planet, it's awful for our lungs, it's just The Worst. Goodbye and good riddance!

Last year, EU CO2 emissions fell by 8%, and the data's not all in for this year yet but they're on track to drop even more. Yeah, you read that right - the EU may have already passed peak carbon emissions. Excuse me while I do a happy dance over here in the corner - this is a BIG FUCKING DEAL!

This may have been a bad year for abortion rights in the US, but we're an outlier - over the past 30 years, we are only one of four countries to tighten abortion restrictions, while 60 countries have made it more available. This year, France became the first country in the whole world to make abortion a constitutional right. Seven US states did so too - Colorado, New York, Maryland, Montana, Nevada, Arizona and Missouri. That's right, Missouri! Shocking, huh?

A drug to prevent HIV infections was 100% effective in trials. That. That's insane. It's not a vaccine, but it is the closest we've ever been to one.

Deaths from tuberculosis, the deadliest infectious disease in the world, hit an all-time global low. Hooray for preventing a truly staggering amount of death!

Egypt and Cabo-Verde both eliminated malaria, and 17 countries started distributing the new malaria vaccine - remember that? Remember how insanely exciting it is that was now have a vaccine for malaria? It is saving lives as we speak.

Deforestation in the Amazon is half what it was two years ago.

The largest dam removal project in history was completed - removing four dams from the Klamath River, thanks to decades of activism by the Karuk and Yurok tribes. A month later, there were salmon spawning in the river basin again - for the first time in a century. Nature's pretty incredible at bouncing back, if we can just give it the chance. I repeat: Largest. Dam removal. In history!

China finished the Great Green Wall

Prewalski's horses returned to their homeland in central Kazakhstan, where they'd been missing for 200 years!

22 endangered species made impressive recoveries - let's hear it for the Saimaa ringed seal, Scimitar oryx, Red cockaded woodpecker, Siamese crocodile, Narwhal, Arapaima, Chipola slabshell and Fat threeridge mussels, Iberian lynx, Asiatic lions, Australian saltwater crocodile, Asian antelope, Ulūlu, Southern bluefin tuna, Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frog, Yellow-footed rock wallabies, Yangtze finless porpoise, Pookila mouse, Orange-bellied parrots, Putitor mahseer (this is a fish), Giant pandas, and Florida golden aster!

This year was deeply shitty in a lot of ways - but not all of them.

Edit: a previous version of this post listed 22 endangered species as being no longer endangered, because I misinterpreted the way my source phrased things. I was wrong - unfortunately at least one of these species (the Saimaa seal) is still endangered, however its population reached about 500 individuals, which is a big deal considering there were only about 100 when they were first listed as a protected species, and between 135-190 adults in 2015 when their population was last assessed for the IUCN. That's still pretty impressive! Thanks to @haltijas for the correction!

Would anyone like to join me in my New Year's tradition of reading about good things that happened this year?

#new years#2024#good news#fix the news#let this be a lesson to read your sources carefully lest you have to tell several thousand people on the internet you made a dumb mistake!#please reblog the updated version so I don't have to be responsible for EVEN MORE accidental misinformation

23K notes

·

View notes

Text

🏞️ !!! happy breaking news !!! after more than 100 years, fall-run Chinook salmon have returned to the Klamath River Basin: one month after the last dam obstacle was removed!!! 🏞️ Mark Hereford, ODFW’s Klamath Fisheries Reintroduction Project Leader, was part of the survey team that identified the fall-run Chinook. His team was ecstatic when they saw the first salmon.

“We saw a large fish the day before rise to surface in the Klamath River, but we only saw a dorsal fin,” said Hereford. “I thought, was that a salmon or maybe it was a very large rainbow trout?” Once the team returned on Oct. 16 and 17, they were able to confirm that salmon were in the tributary.

It marks the return of migrating fish to the area following the removal of four Klamath River dams. The salmon likely traveled 230 miles from the Pacific Ocean.

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Salmon have officially returned to Oregon’s Klamath Basin for the first time in more than a century, months after the largest dam removal project in U.S. history freed hundreds of miles of the Klamath River near the California-Oregon border.

The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife confirmed the news on Oct. 17, a day after its fish biologists identified a fall run of Chinook salmon in a tributary to the Klamath River above the former J.C. Boyle Dam, the department said.”

0 notes

Text

After dam removals, salmon still remember how to reach Klamath tributaries – Darcy Hitchcock

On October 16th, a fall-run Chinook salmon was identified by the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) in a tributary to the Klamath River above the now-demolished J.C. Boyle Dam, becoming the first fish to return to the Klamath Basin in Oregon since 1912 when the first of four hydroelectric dams was constructed, blocking migration. The salmon and others likely traveled about 230 miles…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

So, I really encourage you to do some reading on what pre-contact (and pre-disease contact) ecosystems looked like around here, because it's fascinating. And horrifying, when you put the picture together between all the arms of colonization (disease, wars, intentionally destroying food sources, over hunting beavers, banning traditional practices, etc, etc). Like, really, I started at the same place where you are, and it's incredible.

Here's a little introduction to the oaks: https://www.ecolandscaping.org/05/designing-ecological-landscapes/trees/prairie-oak-ecosystems-pacific-northwest/

With a few quotes:

"Studies show that the genus Quercus hosts more caterpillars and other insect life than any other genus in the northern hemisphere. This proficiency is especially important during breeding season, when the vast majority of land birds consume, and feed their young, highly nutritious larvae, adult insects, and spiders – not seeds or fruit. Other studies show a higher diversity of bird species in oak forests than in nearby conifer forests."

"The historic range of Q. garryana stretches from low elevations of southwestern British Columbia (including Vancouver Island and nearby smaller islands) into California. In Washington, it occurs mainly west of the Cascades on Puget Sound islands and in the Puget Trough, and east along the Columbia River. In Oregon, it’s indigenous to the Willamette, Rogue River, and Umpqua Valleys, and within the Klamath Mountains." "Since Euro-American settlement, as much as 99 percent of the original prairie-oak communities that were present in parts of the Pacific Northwest have been lost and many rare species dependent on them are at risk of extinction. Extensive destruction and fragmentation began with settlement in the 1850s, with clearing, plowing, livestock grazing, wildfire suppression, and cutting of trees for firewood and manufacturing. Prairie wetlands bejeweled with wildflowers were drained and ditched. Later, subsidies to ranchers encouraged more destructive grazing, while urban sprawl and agricultural use, fueled by human population increase, intensified. Invasion of nonnative species, and the encroachment of shade tolerant and faster growing species – that proliferate with fire suppression – outcompeted oaks and displaced or decimated additional native flora and fauna. Prairie-oak ecosystems and associated systems continue to disappear, and isolation of the tiny remaining fragments prevents the migration of wildlife and genetic material from one area to another. Other detrimental factors include diseases and parasites, climate change, and the loss of wildlife that cache acorns and perform other functions."

The thing about Douglas firs, is that they are a pioneer species- they move into prairies and turn them into forests, which obviously displaces that species that are dependent on prairie ecosystems.

Here's a few resources that talk more about this concept in general:

http://w.southsoundprairies.org/documents/Indigenousburning.pdf

I remember reading ethnographic accounts from the tribes in my area, which described what the Puget Sound Basin looked like before contact, and apparently the prairies used to be much more extensive than they currently are, and Douglas firs were seen as a weed in the prairie ecosystems because they were so prone to taking over. But I can't find that resource right now and I need to go because I've got a thing. I may try to find that resource later.

What I was taught growing up: Wild edible plants and animals were just so naturally abundant that the indigenous people of my area, namely western Washington state, didn't have to develop agriculture and could just easily forage/hunt for all their needs.

The first pebble in what would become a landslide: Native peoples practiced intentional fire, which kept the trees from growing over the camas praire.

The next: PNW native peoples intentionally planted and cultivated forest gardens, and we can still see the increase in biodiversity where these gardens were today.

The next: We have an oak prairie savanna ecosystem that was intentionally maintained via intentional fire (which they were banned from doing for like, 100 years and we're just now starting to do again), and this ecosystem is disappearing as Douglas firs spread, invasive species take over, and land is turned into European-style agricultural systems.

The Land Slide: Actually, the native peoples had a complex agricultural and food processing system that allowed them to meet all their needs throughout the year, including storing food for the long, wet, dark winter. They collected a wide variety of plant foods (along with the salmon, deer, and other animals they hunted), from seaweeds to roots to berries, and they also managed these food systems via not only burning, but pruning, weeding, planting, digging/tilling, selectively harvesting root crops so that smaller ones were left behind to grow and the biggest were left to reseed, and careful harvesting at particular times for each species that both ensured their perennial (!) crops would continue thriving and that harvest occurred at the best time for the best quality food. American settlers were willfully ignorant of the complex agricultural system, because being thus allowed them to claim the land wasn't being used. Native peoples were actively managing the ecosystem to produce their food, in a sustainable manner that increased biodiversity, thus benefiting not only themselves but other species as well.

So that's cool. If you want to read more, I suggest "Ancient Pathways, Ancestral Knowledge: Ethnobotany and Ecological Wisdom of Indigenous Peoples of Northwestern North America" by Nancy J. Turner

61K notes

·

View notes

Text

In early October, the first time in 100 years, salmon were observed swimming past the sites of former dams as they migrated from the ocean into the Klamath River. This was made possible by the removal of dams that previously blocked salmon from completing their historic migration.

Interested in learning more? Join the California History Section for their next Speaker Series virtual talk, Toward a Decolonial Future: Klamath River Temporary Dams with Dr. Brittani Orona on Wednesday, November 13 at 4PM. With the four dams removed, this talk will explore the relationship of the lower Klamath River and how Hupa, Yurok, and Karuk story and ceremony intertwine on the Basin to build a new, decolonial future for the river itself.

The event is free but requires registration. For more information and to register, visit https://libraryca.libcal.com/calendar/californiastatelibrary/KlamathRiver .

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Weather: Pacific Northwest

Report generated at 2025-03-27 01:00:11.341382-07:00 using satellite imagery and alert data provided by the National Weather Service.

Flood Watch

WA:

Mason

Hydrologic Outlook

WA:

East Slopes of the Oregon Cascades

Foothills of the Blue Mountains of Washington

Foothills of the Northern Blue Mountains of Oregon

Foothills of the Southern Blue Mountains of Oregon

Grande Ronde Valley

John Day Basin

Lower Slopes of the Eastern Washington Cascades Crest

Northern Blue Mountains of Oregon

Northwest Blue Mountains

Ochoco-John Day Highlands

Simcoe Highlands

Southern Blue Mountains of Oregon

Upper Slopes of the Eastern Washington Cascades Crest

Wallowa County

OR:

East Slopes of the Oregon Cascades

Foothills of the Blue Mountains of Washington

Foothills of the Northern Blue Mountains of Oregon

Foothills of the Southern Blue Mountains of Oregon

Grande Ronde Valley

John Day Basin

Lower Slopes of the Eastern Washington Cascades Crest

Northern Blue Mountains of Oregon

Northwest Blue Mountains

Ochoco-John Day Highlands

Simcoe Highlands

Southern Blue Mountains of Oregon

Upper Slopes of the Eastern Washington Cascades Crest

Wallowa County

ID:

Bear Lake Valley

Bear River Range

Beaverhead/Lemhi Highlands

Big Hole Mountains

Blackfoot Mountains

Caribou Range

Centennial Mountains/Island Park

Challis/Pahsimeroi Valleys

Clearwater

Frank Church Wilderness

Franklin/Eastern Oneida Region

Lost River Valleys

Marsh and Arbon Highlands

Raft River Region

Southern Hills/Albion Mountains

Sun Valley Region

Teton Valley

Wood River Foothills

NV:

Elko

High Surf Warning

OR:

Curry County Coast

South Central Oregon Coast

Flood Warning

OR:

Harney

Wind Advisory

OR:

Central and Eastern Lake County

Harney County

Jackson County

Klamath Basin

Malheur County

Modoc County

Northeast Siskiyou and Northwest Modoc Counties

Northern and Eastern Klamath County and Western Lake County

CA:

Central Sacramento Valley

Central and Eastern Lake County

Coastal Del Norte

Del Norte Interior

Eastern Mojave Desert, Including the Mojave National Preserve

Greater Lake Tahoe Area

Klamath Basin

Lassen-Eastern Plumas-Eastern Sierra Counties

Mineral and Southern Lyon Counties

Modoc County

Mojave Desert Slopes

Mono

Mountains Southwestern Shasta County to Western Colusa County

Northeast Foothills/Sacramento Valley

Northeast Siskiyou and Northwest Modoc Counties

Northern Humboldt Coast

Northern Humboldt Interior

Northern Sacramento Valley

Northern Washoe County

Northern and Eastern Klamath County and Western Lake County

Southern Humboldt Interior

Southwestern Humboldt

Surprise Valley California

Western Mojave Desert

NV:

Greater Lake Tahoe Area

Greater Reno-Carson City-Minden Area

Humboldt County

Lassen-Eastern Plumas-Eastern Sierra Counties

Mineral and Southern Lyon Counties

Mono

Northern Washoe County

Southern Clark County

Spring Mountains-Red Rock Canyon

Surprise Valley California

Western Nevada Basin and Range including Pyramid Lake

High Wind Warning

OR:

Central and Eastern Lake County

Curry County Coast

Modoc County

Northern and Eastern Klamath County and Western Lake County

South Central Oregon Coast

CA:

Central Siskiyou County

Central and Eastern Lake County

Eastern Sierra Slopes of Inyo County

Modoc County

Northern and Eastern Klamath County and Western Lake County

Owens Valley

Winter Weather Advisory

CA:

Northern Trinity

West Slope Northern Sierra Nevada

Western Plumas County/Lassen Park

High Surf Advisory

CA:

Catalina and Santa Barbara Islands

Coastal Del Norte

Coastal North Bay Including Point Reyes National Seashore

Los Angeles County Beaches

Malibu Coast

Mendocino Coast

Northern Humboldt Coast

San Francisco

San Francisco Peninsula Coast

San Luis Obispo County Beaches

Santa Barbara County Central Coast Beaches

Southern Monterey Bay and Big Sur Coast

Southwestern Humboldt

Ventura County Beaches

Lake Wind Advisory

CA:

Greater Lake Tahoe Area

NV:

Greater Lake Tahoe Area

Beach Hazards Statement

CA:

Northern Monterey Bay

Santa Barbara County Southeastern Coast

Santa Barbara County Southwestern Coast

Air Quality Alert

CA:

Coachella Valley

San Gorgonio Pass Near Banning

Flood Advisory

NV:

Elko

2 notes

·

View notes