#King borrowed quite a lot for his Dark Tower series

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Lost Legends

Okay so I read Lost Legends: The Rise of Flynn Rider and general thoughts? It was cute and fun, and I have gripes here and there but I can still recommend it. I don't want to compare it to WOWM because it's like apples and oranges but Lost Legends wins points for me by actually acknowledging the TTS storyline and characters, even though it's kinda brief and not quite as... entertaining.

And before I go into the in-depth spoiler review I'll jot down a few thoughts here: there's a lot to be said about tie-in media and 'canon', but where I think it becomes contentious is where two pieces contradict each other, and whether those contradictions necessitate a canonical hierarchy or cancel something out completely. And the reason I'm bringing this up is because while LL borrows TTS lore it also contradicts it? which is. ironic.

but i'll get into that. Spoilers ahead

Basic Summary of The Plot

Our story starts at the Dark Kingdom, with a short prologue. It's all stuff we already know from the series: King Edmund tries to grab the moonstone, his wife dies, Eugene gets sent away for his own safety. What's funny is that Ms Queen still doesn't get a name, but her Lady in Waiting/Handmaiden gets a name (Maeve), and it's Maeve who really drops the ball on dropping Eugene off at an orphanage instead of raising him as Prince Horace. Go girl give us nothing

And from here the LL timeline begins, as Eugene and Arnie are now twelve year olds (I think?) in an orphanage in Corona. Which is the first contradiction to 'canon' but shelve that thought for now. Eugene and Arnie are good little boys but they're getting too old to keep hanging around and the orphanage needs money for the evil Tax Man, so they decide they'll go off into the world and send some money back when they're rich off their famous adventuring. What happens instead is that The Baron's circus rolls into town (yes that Baron) and Eugene and Arnie decide to try their luck signing up for that gig.

To prove themselves to the Baron, Flynn and Lance have to perform a hazing ritual a heist. The heist is literally just to buy a key from the Weasel but it plays out as this huge dramatic thing with a guard chase which is eternally funny to me because two kids walk into a bar, buy a key and then leave, and it's treated like fucking ocean's eleven. The Stabbingtons try to betray them (those guys are here too) but Flynn and Lance outsmart them, beginning a rivalry for the ages. Also, the pub thugs are all part of the Baron's circus crew. Don't think about it too much.

Anyway, as this has all been going down, Eugene is really interested in getting to talk to this guy with a tattoo of (what we as the audience know is) the brotherhood symbol, which Eugene recognises from the note left with him as a baby. He wants to talk to this dude in the hopes he'll get a clue about who his parents are, but this dude keeps eluding him. He also hasn't had a chance to tell Lance about this yet, so when Lance finds out about it he assumes Eugene only tried to rope him into the circus so he could find his parents and ditch him. Cue an ongoing silent treatment.

Eugene eventually does talk to this guy and he learns that the Brotherhood symbol is from the Dark Kingdom but the Dark Kingdom is gone so he shouldn't bother looking for it. Bummer. And now the Baron is planning a huge heist of the reward money for the Lost Princess' return, and Eugene is getting cold feet. He's been okay with a little bit of thievery so far but this feels like too much for him, and he's not okay with pulling it off but Lance still won't talk to him.

As the plan unfolds, Lance and Eugene reconcile and then they work together to betray the Baron and return the stolen treasure that they stole back to the King and Queen. They get caught by the Baron, escape, then get caught by the guards, but it's okay because they're presented to the King and Queen and when Eugene explains that they felt really sorry about it and promise not to do it again they're let go. And so the story ends on a high note.

My Thots™

Okay so here are the thoughts

Canon Compliance?

The obvious takeaway here is that this story offers you a beautiful pie in the form of the characters you know and love and the established lore, then shoves the pie in your face with things like "Eugene already knows the Dark Kingdom and the Moonstone exist but he never brings this up" and "Eugene betrays the Baron in a very significant way but somehow they'll make up and he and Stalyan will get engaged". Which means that if the integrity of the series is important to you, you'll probably just mentally cross out Eugene knowing about the Brohood/DK/Moonstone.

And imo that's fine! My own approach to this story is a kind of general 'if it works it works, if it doesn't I'll leave it' thing to work my own headcanons around. Because there's a lot of fun things to pluck from, like a new ex-Brotherhood member and other characters that could pop up from Eugene's past and other worldbuilding details.

The Story

The story was pretty short and obviously very tailored towards a younger audience, but it still felt kind of... slow? Mostly because nothing particularly exciting is happening until the big heist and even that feels pretty underwhelming. And of course I don't expect a story like this to be particularly complex and can appreciate its simplicity, but I felt like if it had been longer there could have been more twists to keep things interesting.

For example, the Baron is set up as a character not unlike Gothel, who lavishes praise upon the boys and goes on about how they're 'family' but is obviously just manipulating them and would throw them to the wolves in a heartbeat. Eugene underestimates just how criminal the Baron is, but at no point in the story does the doubt we have in the Baron's sincerity ever amount to anything- Eugene only turns against him because he has a morality crisis, which I'll get to in a minute.

Misc. Thoughts

Okay so one thing I thought was really cute was that each chapter has a little 'quote' from a Flynnigan Rider book, and I wrote them all down so if you've read this far and want me to post those separately lemme know. Anyway I just thought it was a very cute touch.

An honourable mention goes to every time Stalyan shows up, she doesn't really do anything in the story yet still is somehow the only character holding the brain cell. Rapunzel gets an indirect cameo by Lance and Eugene stumbling upon her tower and going "Whoa that's Crazy. Anyway. " which is amazing, and Cassandra even gets a little mention by the Captain! And to answer the question nobody asked, there's a chameleon running around Corona because she's an escapee from the circus, and Pascal's mom's name is Amélie!

Characters - okay really just Eugene

Eugene/Flynn is the title character of the book and we get the story exclusively from his POV, so there isn't a lot to say about Lance. On the one hand while I can acknowledge that this is a story about Flynn, not Lance, there's a few choices that feel like a missed opportunity at best given that this book really was an opportunity to explore Lance's character in a way the series never really does.

And it feels extra egregious when the plot demands conflict between Eugene and Lance, because while the emotion between them is engaging when it's happening, at other times it just feels like a convenient way to shove Lance offscreen again. (As a side note, as contrived as the conflict is these are also two twelve year old boys so. Can't blame em too much).

Also, Eugene coming up with the name "Lance Strongbow" on Lance's behalf while he's unconscious is one of those backstory things I'm not going to be acknowledging, thank you.

The Robin Hood Dilemma

Something I touched on after reading What Once Was Mine is that Eugene's characterisation prior to the movie isn't something writers seem to really like... dealing with. And it kind of makes sense that the author received a lot of characterisation notes from Chris Sonnenburg, because little Flynn does feel very similar to the Eugene we know; only the Eugene we know is an adult man who has since grown out of his Flynn Rider persona. But the Flynn Rider persona he needed to grow out of isn't something that ought to be cast aside entirely!! Stop being cowards!!

Taking a step back, the whole premise of the book is kind of a paradox- because Eugene needs to become Flynn Rider before he can learn to embrace his authentic self, but Flynn Rider isn't hero material, he isn't a good guy, he's not the right protagonist for a story for kids. So what we get isn't Flynn Rider, it's really just Eugene trying on a new name. That works for the beginning of the story, because he is just Eugene trying on a new name, but he doesn't grow into it.

At the beginning of the story, Eugene is an orphan in a poor but still functional orphanage run by a kind old lady, and he is surrounded by nice little boys. Eugene is motivated to leave and get a job by a desire to send funds back to the orphanage, and when he joins the Baron's circus he's taken aback to learn he's among thieves. Here's where I thought: okay, this might get interesting. We might be getting a G-rated 'angel falls from heaven' story about Eugene being morally corrupted by the Baron, of learning that the world outside is tough and he needs to look out for himself first and foremost-

but no. The Baron shares his plan to steal the reward money for the Lost Princess, because all the people he's surrounded himself with are already criminals who don't give a shit, but Eugene thinks that this is going too far! What about that poor lost princess who people need an incentive to search for? (he's like, projecting about his own parent issues which is fair, but still). And so the story ends with Eugene turning on the Baron to return the money to the "right" people (aka the king and queen of a kingdom?? okay) but he takes a single golden egg for himself so he can send it to the orphanage.

Which is all sweet and nice but. He still has to become Flynn Rider, asshole extraordinaire. He still has to lose his morals to the point where he'd take an inexperienced young woman to a pub that he, in this book, recognises is a dangerous place in the hopes that he can ditch her. He still has to go and become a wanted thief and rejoin the Baron and then ditch Stalyan on their wedding night.

The reason I'm going on about this so much is that the appeal of Eugene to me is that he is this good guy who wants to be a better person for the people he loves, but that means recognising that he has behaviour he needs to change, and his development is meaningful for that. Watering him down to a righteous Robin Hood hero does him a disservice.

The Real Villain Was Capitalism All Along

I will not elaborate nor should I

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came

Robert Browning

Child Rowland to the dark tower came, His word was still 'Fie, foh, and fum I smell the blood of a British man. Shakespeare ‘King Lear’, act 3, scene 4

My first thought was, he lied in every word, That hoary cripple, with malicious eye Askance to watch the working of his lie On mine, and mouth scarce able to afford Suppression of the glee, that purs’d and scor’d Its edge, at one more victim gain’d thereby.

What else should he be set for, with his staff? What, save to waylay with his lies, ensnare All travellers who might find him posted there, And ask the road? I guess’d what skull-like laugh Would break, what crutch ’gin write my epitaph For pastime in the dusty thoroughfare,

If at his counsel I should turn aside Into that ominous tract which, all agree, Hides the Dark Tower. Yet acquiescingly I did turn as he pointed: neither pride Nor hope rekindling at the end descried, So much as gladness that some end might be.

For, what with my whole world-wide wandering, What with my search drawn out thro’ years, my hope Dwindled into a ghost not fit to cope With that obstreperous joy success would bring,— I hardly tried now to rebuke the spring My heart made, finding failure in its scope.

As when a sick man very near to death Seems dead indeed, and feels begin and end The tears and takes the farewell of each friend, And hears one bid the other go, draw breath Freelier outside, (“since all is o’er,” he saith, “And the blow fallen no grieving can amend;”)

While some discuss if near the other graves Be room enough for this, and when a day Suits best for carrying the corpse away, With care about the banners, scarves and staves, And still the man hears all, and only craves He may not shame such tender love and stay.

Thus, I had so long suffer’d, in this quest, Heard failure prophesied so oft, been writ So many times among “The Band”—to wit, The knights who to the Dark Tower’s search address’d Their steps—that just to fail as they, seem’d best. And all the doubt was now—should I be fit?

So, quiet as despair, I turn’d from him, That hateful cripple, out of his highway Into the path the pointed. All the day Had been a dreary one at best, and dim Was settling to its close, yet shot one grim Red leer to see the plain catch its estray.

For mark! no sooner was I fairly found Pledged to the plain, after a pace or two, Than, pausing to throw backward a last view O’er the safe road, ’t was gone; gray plain all round: Nothing but plain to the horizon’s bound. I might go on; nought else remain’d to do.

So, on I went. I think I never saw Such starv’d ignoble nature; nothing throve: For flowers—as well expect a cedar grove! But cockle, spurge, according to their law Might propagate their kind, with none to awe, You ’d think; a burr had been a treasure trove.

No! penury, inertness and grimace, In the strange sort, were the land’s portion. “See Or shut your eyes,” said Nature peevishly, “It nothing skills: I cannot help my case: ’T is the Last Judgment’s fire must cure this place, Calcine its clods and set my prisoners free.”

If there push’d any ragged thistle=stalk Above its mates, the head was chopp’d; the bents Were jealous else. What made those holes and rents In the dock’s harsh swarth leaves, bruis’d as to baulk All hope of greenness? ’T is a brute must walk Pashing their life out, with a brute’s intents.

As for the grass, it grew as scant as hair In leprosy; thin dry blades prick’d the mud Which underneath look’d kneaded up with blood. One stiff blind horse, his every bone a-stare, Stood stupefied, however he came there: Thrust out past service from the devil’s stud!

Alive? he might be dead for aught I know, With that red, gaunt and collop’d neck a-strain, And shut eyes underneath the rusty mane; Seldom went such grotesqueness with such woe; I never saw a brute I hated so; He must be wicked to deserve such pain.

I shut my eyes and turn’d them on my heart. As a man calls for wine before he fights, I ask’d one draught of earlier, happier sights, Ere fitly I could hope to play my part. Think first, fight afterwards—the soldier’s art: One taste of the old time sets all to rights.

Not it! I fancied Cuthbert’s reddening face Beneath its garniture of curly gold, Dear fellow, till I almost felt him fold An arm in mine to fix me to the place, That way he us’d. Alas, one night’s disgrace! Out went my heart’s new fire and left it cold.

Giles then, the soul of honor—there he stands Frank as ten years ago when knighted first. What honest man should dare (he said) he durst. Good—but the scene shifts—faugh! what hangman hands Pin to his breast a parchment? His own bands Read it. Poor traitor, spit upon and curst!

Better this present than a past like that; Back therefore to my darkening path again! No sound, no sight as far as eye could strain. Will the night send a howlet of a bat? I asked: when something on the dismal flat Came to arrest my thoughts and change their train.

A sudden little river cross’d my path As unexpected as a serpent comes. No sluggish tide congenial to the glooms; This, as it froth’d by, might have been a bath For the fiend’s glowing hoof—to see the wrath Of its black eddy bespate with flakes and spumes.

So petty yet so spiteful All along, Low scrubby alders kneel’d down over it; Drench’d willows flung them headlong in a fit Of mute despair, a suicidal throng: The river which had done them all the wrong, Whate’er that was, roll’d by, deterr’d no whit.

Which, while I forded,—good saints, how I fear’d To set my foot upon a dead man’s cheek, Each step, or feel the spear I thrust to seek For hollows, tangled in his hair or beard! —It may have been a water-rat I spear’d, But, ugh! it sounded like a baby’s shriek.

Glad was I when I reach’d the other bank. Now for a better country. Vain presage! Who were the strugglers, what war did they wage Whose savage trample thus could pad the dank Soil to a plash? Toads in a poison’d tank, Or wild cats in a red-hot iron cage—

The fight must so have seem’d in that fell cirque. What penn’d them there, with all the plain to choose? No foot-print leading to that horrid mews, None out of it. Mad brewage set to work Their brains, no doubt, like galley-slaves the Turk Pits for his pastime, Christians against Jews.

And more than that—a furlong on—why, there! What bad use was that engine for, that wheel, Or brake, not wheel—that harrow fit to reel Men’s bodies out like silk? with all the air Of Tophet’s tool, on earth left unaware, Or brought to sharpen its rusty teeth of steel.

Then came a bit of stubb’d ground, once a wood, Next a marsh, it would seem, and now mere earth Desperate and done with; (so a fool finds mirth, Makes a thing and then mars it, till his mood Changes and off he goes!) within a rood— Bog, clay, and rubble, sand and stark black dearth.

Now blotches rankling, color’d gay and grim, Now patches where some leanness of the soil’s Broke into moss or substances like thus; Then came some palsied oak, a cleft in him Like a distorted mouth that splits its rim Gaping at death, and dies while it recoils.

And just as far as ever from the end, Nought in the distance but the evening, nought To point my footstep further! At the thought, A great black bird, Apollyon’s bosom-friend, Sail’d past, nor beat his wide wing dragon-penn’d That brush’d my cap—perchance the guide I sought.

For, looking up, aware I somehow grew, Spite of the dusk, the plain had given place All round to mountains—with such name to grace Mere ugly heights and heaps now stolen in view. How thus they had surpris’d me,—solve it, you! How to get from them was no clearer case.

Yet half I seem’d to recognize some trick Of mischief happen’d to me, God knows when— In a bad perhaps. Here ended, then, Progress this way. When, in the very nick Of giving up, one time more, came a click As when a trap shuts—you ’re inside the den.

Burningly it came on me all at once, This was the place! those two hills on the right, Couch’d like two bulls lock’d horn in horn in fight, While, to the left, a tall scalp’d mountain … Dunce, Dotard, a-dozing at the very nonce, After a life spent training for the sight!

What in the midst lay but the Tower itself? The round squat turret, blind as the fool’s heart, Built of brown stone, without a counter-part In the whole world. The tempest’s mocking elf Points to the shipman thus the unseen shelf He strikes on, only when the timbers start.

Not see? because of night perhaps?—Why, day Came back again for that! before it left, The dying sunset kindled through a cleft: The hills, like giants at a hunting, lay, Chin upon hand, to see the game at bay,— “Now stab and end the creature—to the heft!”

Not hear? when noise was everywhere! it toll’d Increasing like a bell. Names in my ears Of all the lost adventurers my peers,— How such a one was strong, and such was bold, And such was fortunate, yet each of old Lost, lost! one moment knell’d the woe of years.

There they stood, ranged along the hill-sides, met To view the last of me, a living frame For one more picture! in a sheet of flame I saw them and I knew them all. And yet Dauntless the slug-horn to my lips I set, And blew “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower came.”

#poetry#color’d gay and grim#surprisingly anticlimactic#i was expecting a full story#i wasn't prepared for poe/lovecraftian horror introspection#inspired some damn deep interpretations#King borrowed quite a lot for his Dark Tower series#road story#the goal is journey not the tower

0 notes

Text

the belly of an architect

When The Beginner’s Guide was released in late 2015, there was a sense that the current lexicon of video game writing was somehow inadequate to properly describe it. Here was something that was entirely in keeping with every trend in indie games: it was personal, political, metafictional; it was witty and ironic, in the highest sense of those terms; it was a game about games, and it was a game about people. It was also funny, visually inventive, and above all it felt like something genuinely new. It was received with good reviews, tempered with caution. Even players who were affected by it seemed to hold it at arm’s length. Much like the sight of somebody having an emotional breakdown in public, the implication was that it was powered by something that was somehow beyond criticism.

The game had a certain amount in common with The Stanley Parable, the previous work by creator Davey Wreden. Both games are told from the first-person perspective with 3D graphics, and place a very limited range of interactions at the player’s disposal. There is not much to do in these games; you wander alone through a world while an unseen narrator comments on what you’re doing and what you are looking at. Indeed, The Beginner’s Guide is even more limited in this respect than The Stanley Parable — there are none of the alternative paths, hidden endings and secrets that many players found so endearing in the latter title. But both games are full of jokes about the absurdities of game design, and in spite of their sometimes acerbic tone, both are made with a rich empathy for players and designers alike.

Where things differ is in the uneasy relationship of The Beginner’s Guide to reality. It purports to be a set of unfinished games originally created by somebody called Coda. (This requires some suspension of disbelief: we know from the credits that a small team of other people worked on this game as well, but within the fiction of the game, they might as well not exist.)

The story goes that Wreden has spliced fragments of Coda’s creations together into a semi-coherent experience in the hope of demonstrating the work of his talented friend. As the player moves through Coda’s worlds, Davey’s voice is their tour guide. His explanations provide a ‘story’ to what otherwise might seem a totally abstract set of design decisions. But Davey is more than a narrator: he’s the architect of the entire experience, warping the player from one section to the next, and often interfering directly with Coda’s work in order to make it possible to play.

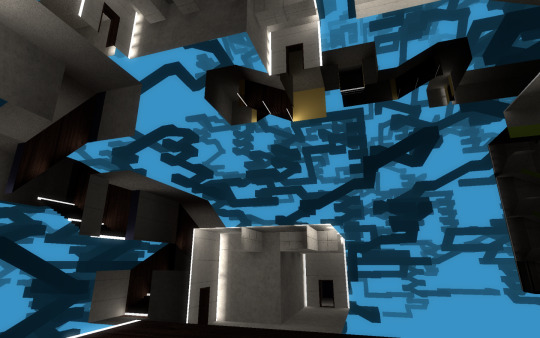

This question of possibility is key to understanding The Beginner’s Guide. For Davey, everything in life seems possible, or can be made so; for Coda, it’s the opposite. Coda was, we are told, a socially awkward person. To borrow a phrase from Sarah Baume, he is ‘not the kind of person who is able to do things’. Yet Coda’s levels seem quite straightforward at first. He dabbles with a map for Counterstrike, and a science fiction thing that almost feels like the start of a ‘real’ game. But even in those early examples, his work demonstrates a tendency to add inexplicable elements which interrupt the experience entirely.

A bizarre bug in the sci fi game means that if the player walks into a laser beam — which they have to do in the absence of other options, even though they know it’ll kill them — they actually end up floating slowly through the ceiling, and then up and out of the map, so that the whole of the crafted space is visible to them. Is this a sort of expressionism, or is it simply a mistake? Why would somebody put something like that in a game? What were they trying to tell us?

The basic situation between Davey and Coda is emblematic of a certain tension present in the way we think about games today. On one side, we have the idea of games as personal expression: the idea that in a game one might be able to turn one’s own experiences into a kind of machine for empathy. On the other, there’s the notion that games don’t need to be ‘about’ anything except their own mechanics: that they should be accessible and rewarding and coherent and, you know, fun. The Beginner’s Guide is an attempt to resolve this tension -- both within a creator’s work, and their life. Is it possible to make a game which is complete, rational and enjoyable, when none of those things are true of life?

The personal approach is Coda’s modus operandi, but his games aren’t expressive in any kind of straightforward way. At times, they have all the cold unreality of conceptual art. And it’s hard to tell how they might be encountered in isolation, since as it stands, they can only be appreciated alongside the insight that Davey provides into their methodology. He’s like the curator of an exhibition who creates an experience by placing one work alongside another, by colouring the backdrop, by writing the cue cards. At every stage we are told what to think about we are seeing. And like any good critic, Davey isn’t hesitant to root around in the guts of Coda’s work if it means he can get his point across better.

(considerable spoilers to follow.)

Davey finds a lot of things to show that were never meant to be seen at all. A distinguishing feature of video games is that a great deal of extra craft can be present in the work itself, but also be totally invisible to the audience, even though it represents a deliberate artistic gesture. Imagine a writer who encoded whole extra passages in a novel by sealing them up within the endpapers: the equivalent of this comes early on in The Beginner’s Guide when Davey strips away the walls of an innocuous hallway to reveal a vast network of interconnected passages floating in the void; an entire hidden labyrinth, forever unreachable by the player.

This is emblematic of the eternal problem for Davey. Coda’s games were never intended to be ‘played’ in the commonly understood sense. Coda created a staircase that would slow the player’s movement speed in proportion to their progress along it, making it almost impossible to ever reach the top. He built a cell within a huge, elaborate prison, where the player had to spend hours and hours in real time before they would be allowed to proceed. In one of his more detailed creations, Coda made a little house in which the player can only repeat a cycle of tedious domestic chores while a nameless companion provides a stream of inanely optimistic chatter. Davey allows the player a taste of all these, but he cuts them short too. For him, the work cannot be allowed to speak for itself: context is king. And who else is there to provide context but Davey?

Over time, Davey begins to build up a portrait of Coda in the player’s mind. These are the creations of a person who is anxious and depressed. This is the work of someone who is subject to a kind of creative paralysis; a sense of crippling inertia which sees him repeating the same small, obsessive routines that have damaged his personal life. In Davey’s version of their relationship, Davey himself only exists as a helpful counterpoint. He tells the player how he encouraged Coda to share his work, and to make it more accessible to a wider audience by toning down some of the more difficult aspects. And eventually, Coda’s creations begin to take on a different shape. Davey is delighted to point out when a clearly defined end point appears in the levels, marked by an old-fashioned lamp post.

But at the same time, things seem to be progressing towards a very uncertain place. In this sense, the ending of The Beginner’s Guide has a certain shape to it reminiscent of Gone Home. Players approach both having worked through a great deal of dark subject matter, much of which suggests that something horrifying might be around the final corner. But instead, the game has one final curveball to throw.

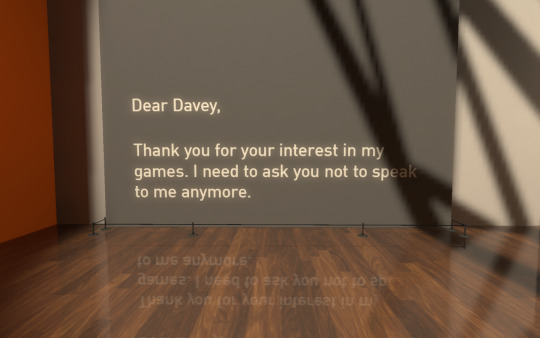

The last world Coda shared with Davey was his most impressive, and his most demanding. An enormous tower that stretches upwards through endless dark space. To approach it, the player has to make it through a maze with invisible walls: touching any wall means death. And even if they manage to get through this, there’s a locked door where the switch is on the other side of the door — it’s simply impossible to open. (As ever, Davey is on hand to warp the player past both of these obstacles, if they choose.)

Once the player has passed through every one of Coda’s impossible challenges, they find a gallery, with a series of messages on the walls.

‘Would you stop taking my games and showing them to people against my wishes?’

‘Would you stop changing my games? Stop adding lamp posts to them?’

‘The fact that you think I am frustrated or broken says more about you than about me.’

This, then, is the real story of The Beginner’s Guide. It is a confession of sorts: Davey’s interference with Coda’s work has gone beyond packaging it in an accessible way. He’s adopted it entirely. And as Davey explains, in a rare moment of honesty, he’s come to directly identify with certain aspects of it. Coda’s worlds express something that Davey’s conventional persona cannot talk about. And Davey wanted to share them with the world because the ensuing admiration made him feel valued; but in doing so, he may have destroyed something essential about them.

Perhaps Coda wasn’t a depressed person after all. His messages to Davey seem to suggest as much; or as Davey puts it: ‘Maybe he just likes making prisons’. Depression and anxiety are not generally conducive to creativity, and Coda was nothing if not creative.

But we aren’t quite at the end of the game.

The final sequence is an epilogue. It’s the only part of the game which isn’t framed as Coda’s work.

A train station leads to a windowless train carriage. The train leads to a station outside a stately home, the lofty rooms filled empty but for heaps of sand. More caves, more columns of dark and light. Then we are out into a little empty abstract space of bright yellows and blue skies, a visual tone not dissimilar to Coda’s first map for Counterstrike. And then down a little hole in the ground and we’re in that space ship again from the start of the game. Here again is that laser beam, so strangely broken; what do you think will happen if the player walks into it?

Davey is talking again, but this time from the heart. He’s no longer interpreting, nor commenting on the environment: he’s just telling us how he feels. It’s refreshing, and true. In this moment, what we have suspected all along comes to pass: Davey and Coda have become one and the same.

It’s to the game’s credit that a player might feel uncomfortable at this stage, as though they had accidentally wandered into a personal conflict between two old friends. But nothing happens by accident here, no more than it does in any other video game. The question of whether or not Coda ought to be considered a ‘real person’, so often raised around the release of The Beginner’s Guide, is not without interest; but not for the reasons many people thought. In the reality of the game, Coda is no more or less fictional than Davey Wreden.

The world was always Davey’s, in every sense. Perhaps Coda was only ever a part of him: one that he originally believed he could hold at an arm’s length, but which he eventually comes to embrace. By the time we reach the end, he’s absorbed Coda’s lessons and moved beyond them. He knows that the home is a prison, and that the prison is the maze, and that the maze is a the world. He’s realised that it might be possible to create a thing which is both an entertaining experience and a valid means of personal expression, without necessarily telling the player how to feel about it at every juncture. In other words, he’s ready to create something that looks a lot like The Beginner’s Guide.

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A must for any Dark Tower Fan A must for any Dart Tower fan - A very well done graphic novel adaptation of this story that is not included the DT novels, originally appearing in a collection of short stories (which I can't remember at the moment - the cover {if I'm not mistake} of one of the editions has a goblet style water glass with droplets of blood in the water). Go to Amazon

Watch out for the Little Sisters! I love Stephen King so when I discovered that he would not be writing the graphic novels relating to "The Dark Tower" series, I was a bit skeptical. I'm sorry I doubted you Robin Furth and company. I purchased the first dark Tower Graphic issues and stopped purchasing them as I found them difficult to locate (could not find local comic stores)as individual graphic issues. So I started purchasing the Graphic Novels (for those that are not aware, there are several issues comprising an individual story directly correlating to "The Dark Tower" story that come out every few months and once that series has been completed, the issues are compiled into a hardcover Graphic Novel). I started buying the completed Graphic Novels when "Treachery" was available and have been buying them since. The stories and background information is incredible not to mention the artwork. If you are even remotely interested in Stephen King's The Dark Tower" series of novels, these graphic novels are a must! Go to Amazon

No more The Dark Tower series needed to end with Roland finding the tower. Stop with the ridiculous money grabbing terrible follow ups. Go to Amazon

Creepy This graphic novel is probably the best adaptation of Stephen King's Roland story, and is definitely the most creepy and horrific. It follows king's short story very well, and the artistry is excellent! There's a lot of violence and gore, and the drawings live up to the horror of the original story. I have gotten a lot of enjoyment out of this entire series, but this one tops all of the others. Hopefully, the writers and artists can keep up the good work they have been doing, and giving all of the Stephen King fans a visual treat, and a pictorial glance into the Dark Tower story. Go to Amazon

Great artwork, does justice to the novel. I'm a big Stephen King/Dark Tower fan. I've been collecting the Dark Tower Series comics since they launched, they do justice to the novels, quite possibly the best part of these books is the back section with the history of the worlds, they really open your eyes to whats going around. Even if you're a purist of the sort that doesn't want to read comics these are worth picking up just for the back section. Go to Amazon

What we've been waiting for The Little Sisters of Eluria is the only Dark Tower piece written by Stephen King that I have not read. I have also avoided the majority of the preceding Dark Tower comic arcs because the writers don't have Stephen King's talent for horror. Despite not having read the actual short story, I could tell that this was King's work and not anyone else's. When you get to this arc you finally get a taste of King's ability and it is a stark contrast to the other comic arcs. This arc is a huge upgrade in quality. It's night and day. Go to Amazon

Dark Tower Awesome continuation of the adventures of Roland. A faithful representation of the short story found in Stephen King's Everthings Eventual. I discovered this Dark Tower story after I had finished the series and absolutely loved it so when they announced it was the next in the series I was excited. It was worth the wait because it was faithfully captured within these pages. The art really brought it to life and with the next chapter being Tull we are officially in the first novel. Can't wait for the next collection. Also reviewed by me on TFAW.com a comic shop. Go to Amazon

Great Story, Great Art! The Dark Tower Series is the best King fantasy series. We waited anxiously as each new book came out. Now it is out in a graphic novel. This is a great find for my grandson in Afganistan. He treasures each book and anxiously awaits the next one. His friends eagerly wait for him to finish reading so they can borrow the next one. A great adventure to read, and great to share with others who live a hurry up and wait lifestyle with their lives on hold and sometimes on the line. Go to Amazon

Five Stars Dark tower book great Art work and story line Good interlude Sadly not up to scratch Exellent. Five Stars If you like the Dark Tower series Five Stars Fleshes out the Little Sisters of the Dark Tower series

0 notes

Text

REVIEW: The Dark Tower - Just about stays standing

At the centre of the film universe lies the most powerful force in existence... us. Whether we like it or not, as films are made and shaped in response to consumer trends our every decision decides our future. If we support a CG driven action movie, they’ll be many others like it (<insert Transformers reference>). If we mention that films are taking themselves too seriously we get things Deadpool in response. Everything is connected. That’s why we’re most definitely responsible for this summer’s trend of shorter running blockbusters. For years people have been vocally against films more commonly reaching 2 or even hours in length. So naturally filmmakers will see a shorter run time as a more marketable attribute. While ether cases like Dunkirk of this being a success (I couldn’t have taken 2 + hours of that intensity) there are sadly more cases of these cut run times having detrimental effects on their films. Dark Tower becomes the latest casualty of the short run summer; losing some of its magic from fast tracking out its story.

At the centre of the Universe stands The Dark Tower, pretending all from the monsters that lie beyond. The troubled young Jake (Tom Taylor – The Last Kingdom) may be the key to bringing it down for the Man in Black (Matthew McConaughey – Interstellar) unless the Gunslinger (Idris Elba – Pacific Rim) can stop him.

Now I’m an 80s child; you give a young protagonist adventuring into a fantasy world and I’m all yours and The Dark Tower has more than enough potential to spark my interest. Yet my biggest problem with this adaptation of Stephen King’s literary world was its lack of depth; or rather how much of it the film skips over while racing through its story. The “Mid-World” is shown as being post apocalyptic without any explanation, with vastly inconsistent levels of technology and barely any thought given to its inhabitants. No, I don’t have the shine but I what you’re thinking fanboy. The connected 2018 TV series (in which Idris Elba & Tom Taylor will reprise their roles) is supposed to be filling in the back story of the book series. That’s all well and good and hopefully will result in a deep and rewarding viewing when able to watch them all together. Yet that does not help The Dark Tower as single viewing experience, especially for casual cinema goers less concerned over waiting a year to fill in the blanks. Director Nikolaj Arcel would have been better off keeping his mind in the present and giving us more to go on. Instead Mid-World feels like a generic cut and paste of studio back lot sets and props.

However, despite some rushing I did like the overall story of The Dark Tower. It carried good classic themes good Vs evil with underlying ideas heroism and sacrifices for the greater good. The Gunslinger is the last hero standing and broken because of it. The events move well enough from location to location and returning to “Keystone Earth” aka Earth provides some good fish out of water material for Elba to play with. What’s more its position as a story continuation rather a book adaption is rather fascinating. For those that haven’t read the books the series concluded in a tad on the timey whimey. After finally reaching the end of his journey at The Dark Tower the Gunslinger wakes up back where it all began with no memory of the events but carrying an artefact he didn’t have last time and whispered message that if he reaches it again the result might be different. So that is the story they’re picking in the films. It’s almost like a 2009 Star Trek reboot, only sticking closer to its original events.

The visuals are at times very impressive and although there is occasional stretch on believability the gun fighting based action set pieces are entertaining and occasionally thrilling. Seeing Elba face down vast ranks of assault rifle wielding minions with a pair of six shooters makes the villains look incompetent more than the hero strong but this is saved by focusing on The Gunslinger’s precision and skill. Despite this the film loses itself in its western theme and there some frustrating points where the story doesn’t give events enough time to sink in and be impactful. The atypical fall out at the two thirds point between the heroic pair lasts barely 2 minutes before they’ve completely moved passed it, leaving it feeling rather pointless.

Another casualty of the condensed running time is villain quality. The Man in Black is quite literally Matthew McConaughey in a black shirt that’s borrowed a few tricks from Killgrave. He has no depth and no discernible personality other a Family guy interpretation of Matthew McConaughey. Similarly his lieutenants are rarely named, given significant screen time or given anything to do other than being a physical presence. The heroes fair better. Elba is certainly believable in his grub stubbornness being the product of his tragedy and holds the film together like its titular Tower. Similarly young Taylor is decent as Jake. He gets almost no establishment time to sell his , “troubled kid” angle but in fact does a lot better with it than he really should. There are moments when he seems to lose his character but despite taking a few hits he stands strong.

So The Dark Tower is an affair of promise Vs problems. It’s the promise of an interesting developing story and a decent lead pair pairing against problems of execution. The future of this tower now rests firmly on the 2018 TV show. If that delivers and successfully fleshes out the world than a potential film sequel could get away with this kind of rushing. It the show crumbles then there’s no rebuilding this tower. I’d call this film worth a watch for genre fans but keep in mind that you’re not getting the full picture.

0 notes

Text

Gold

A rising star in the 1990s only to wind up being written off as a pretty face in the 2000s, Matthew McConaughey found the first half of the 2010s to be the kindest and most successful of his career. Starring in critical hit after critical hit, McConaughey nabbed financial success via Magic Mike and Interstellar and netted Oscar gold in Dallas Buyers Club. Toss in some of the best performances of the decade in indie darling Mud and HBO series True Detective and the early 2010s are guaranteed to go down as the most successful critical stretch of the Texan actors career. Since then, however, he has struggled. From Gus Van Sant's stinker The Sea of Trees to the mixed Free State of Jones (which, as a McConaughey apologist, I liked), McConaughey's live action worked has slumped. In fact, aside from an animated turn in Kubo and the Two Strings, he has not been in a truly good film since 2014. It may not seem like that long of a time period, but for a man who made appearances in eight critical darlings between 2011 and 2014 plus an acclaimed television series in the time period, it is a real drought especially considering he was in five films in 2016.

One can see what drew him to Gold. Directed by Stephen Gaghan, Gold marked Gaghan's first directorial work since 2005's Syriana. For Gaghan to get up and direct again, it likely had to be one heck of a script. With the project having roots in 2011 with Michael Mann and Christian Bale sniffing around it, one cannot be blamed for being elated to see this modern day Treasure of the Sierra Madre pop up with Gaghan at the helm and McConaughey in the leading role. The end result, however, is a rather safe film that is enjoyable, often truly engaging, but always a big sloppy mess. One thing is for sure though: it is not a mess due to McConaughey, who once more fires on all cylinders. He is, however, starting to lose much of that good will built up in the "McConaissance". Should his next two projects, The Dark Tower and White Boy Rick, also be met with a mixed reception, who knows what the future will have in store for the man.

Treasure of the Sierra Madre this is not , however, even with Gaghan snatching the themes from that film of desperation, hope, greed, and dreams of striking it rich, and tossing it into this real life tale of two men who had fooled everyone into thinking they had the biggest gold find of the 1980s. A rags to riches tale, the film feels as though it is trying to play off of recent financial scam films such as The Wolf of Wall Street or The Big Short with the film being somewhat tongue-in-cheek and often told through narration. With the narration being in the form of an FBI interview, the film hardly earns any originality points. Taking the party scenes of those aforementioned financial films, blended with a gangster-style story of a man who strikes it rich, fights with his wife and dumps her for blonde bimbos, and has uproariously insane encounters abroad and at-home, Gold is a film that has been done many times before. For this, it is rather disappointing to watch in many respects given its general stale quality and the eternal feeling that this has all been done before.

Featuring a 1980s punk rock soundtrack that includes Joy Division, Iggy Pop, and Depeche Mode, Gold is a film about a moron and a genius coming together to strike it rich. The moron, Kenny Wells (Matthew McConaughey), is along for the ride. Michael Acosta (Edgar Ramirez) is a skilled con artist who, when Wells comes up to him with an offer to drill wherever, he opts to go 50-50 with the man and takes the financial world for a ride. Kenny, flush with cash and newly single from Kay (Bryce Dallas Howard), parties it up with naked blondes and has more play money than a man with his mental capacity should have. This punk rock party music accompanies these party scenes and adds this loose and casual nature to these scenes where it is easy to see that these moments are fleeting and the cash disposable. Kenny, a classic figure of a man who wishes to get rich but has no idea how to not be poor, rapidly finds himself in a position where all of the fame, fortune, and notoriety has crumbled around him. Right when he thought he was king of the world, it turned out everything he thought he knew could not have been further from reality.

The film’s clichés do hold it back as previously mentioned, but they are hardly detrimental. On the surface, its story and themes are compelling even if Gaghan breaks no new ground. In fact, in its depiction of a man who is just along for the ride rather than the mastermind himself, Gold does manage to set itself apart from any number of similar biopics. Unlike other films, this one gives you a hero who is an awful businessman and constantly makes the wrong decision, ensuring that the audience will recognize he could never be the mastermind behind this scandal. That said, the film’s refusal to really break out of classic biopic formula and hitting all of the checkmarks on a “rags to riches” tale is frustrating. What saves the film throughout, however, is the strong pairing of Matthew McConaughey and Edgar Ramirez. Together, the really embody the spirit of prospecting and have a clear passion for it, especially McConaughey’s Kenny Wells. Playing this boisterous man who is well past his frame physically and mentally, McConaughey ditches the easy coolness he is known for, in favor of an off-putting desperation. Wells is a man who needs a hit and knows he does. Putting his life and finances on the line to try and make his dream come true, McConaughey captures this desperation, anger, frustration, and undeniable sadness perfectly. He is a truly tragic figure that garners great sympathy, especially when McConaughey’s nervous energy in the role shines through during the entirety of the film. Alongside him, Ramirez is believable as the two-sided Michael Acosta. A good friend to Kenny, but a bit too self-absorbed and sleazy, he is a man who is believable as someone who would rip others off. Ramirez brings a great calmness to the role with him always in control and in full knowledge of that fact. Compared to McConaughey’s out-of-control downward spiral, Ramirez’s Acosta exudes confidence that only comes from knowing it is all rigged.

That said, the editing leaves a lot to be desired, as does the direction. With Stephen Gaghan clearly trying to pigeon hole this film into becoming a standard biopic, Gold feels rather sliced and diced. Some scenes, especially early on, end far too early. Others drag on. Some never really establish why they are there beyond being pure exposition, providing unnecessary detail, and trying to garner sympathy for the characters. Some moments, especially those in Indonesia especially with the initial dream-inspired trip are woefully short. The inciting action of the film, Kenny Wells having a dream about gold in Indonesia, is largely rendered pointless. With the film only showing the brief dream sequence before whisking him away to Indonesia to show us nothing more than the same image as before, it feels as though Gaghan was in a hurry to get the film really going. The pacing, as a result, feels rather awkward. At times, such as in that aforementioned moment, Gold acts like a college student wrapping up a paper that is due in five minutes. At other moments, however, it is like a college student who just assigned a huge project due in two weeks. As is often the case with that college student, there is no balance or natural flow to this film. Instead, it feels as though it is a film constantly trying to find itself and that remains unsure of what it is really supposed to all mean in the end. It is rather enjoyable, but it is hard to describe Gold as anything better than being a mess or being like a compilation album of all of cinema’s greatest biopic hits.

In spite of its flaws, Stephen Gaghan's Gold is a fine film. With strong performances across the board, the film's energy and general entertainment value do help it overcome many of its issues. Its fragmented feeling, general reliance upon cliches, and heavy borrowing of the style of other similar tales in recent times and in film history, do render Gold a largely typical experience. In this case, however, typical feels quite nice given the film's engrossing true story and characters that would have been better served by an improved film, but remain compelling all the same.

#gold movie#gold#2016 movies#2010s movies#film reviews#film analysis#stephen gaghan#matthew mcconaughey#edgar ramirez#bryce dallas howard#corey stoll#bruce greenwood#joshua harto#rachael taylor#toby kebbell

0 notes