#Kenley Residents Association

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

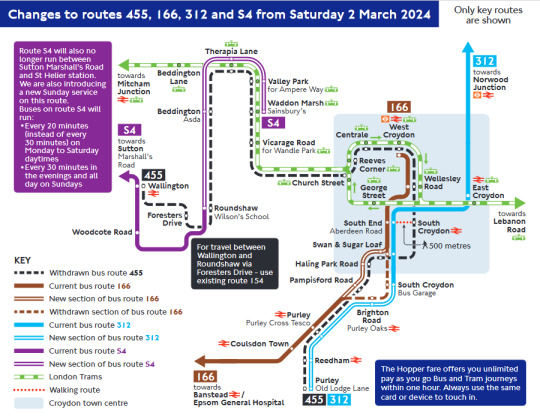

How TfL's changes to 10 Croydon bus routes will affect you

There’s major changes coming to 10 bus routes serving the south of Croydon, including Purley, Coulsdon, Kenley and South Croydon, as well as Sutton and Wallington, coming into effect on Saturday March 2. Here’s TfL’s blow-by-blow breakdown of their bus route changes: Routes 455, 166, 312 and S4 Route 455 Route 455 will be withdrawn. Use alternative bus routes. Continue reading How TfL’s changes…

View On WordPress

#Charles King#Coulsdon#Croydon#Croydon Council#East Surrey Transport Committee#Kenley#Kenley Residents Association#London#London Buses#Neil Garratt#Old Coulsdon#Purley#Purley Hospital#Purley Way#Route 455#South Croydon#St Helier#Sutton#Sutton Council#TfL#Transport for London#Wallington

0 notes

Text

Karamu House

2355 E. 89th St.

Cleveland, OH

Karamu House at 2355 East 89th Street, in Cleveland, Ohio, in the Fairfax neighborhood on the east side of Cleveland was built in 1952, was designed by Small, Smith, Reeb, Draz, architects, and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It is the oldest producing Black Theatre in the United States opening in 1915. Many of Langston Hughes's plays were developed and premiered at the theater.

In 1915, Russell and Rowena Woodham Jelliffe, graduates of Oberlin College in nearby Oberlin, Ohio, founded what was then called The Neighborhood Association at 2239 E. 38th St.; establishing it as a place where people of all races, creeds, and religions could find common ground. The Jelliffes discovered in their early years, that the arts provided the common ground, and in 1917 plays at the "Playhouse Settlement" began.

The early twenties saw a large number of African Americans move into an area in Cleveland, from the Southern United States. Resisting pressure to exclude their new neighbors, the Jelliffes insisted that all races were welcome. They used the United States Constitution; "all men are created equal." What was then called the Playhouse Settlement quickly became a magnet for some of the best African American artists of the day. Actors, dancers, print makers, and writers all found a place where they could practice their crafts. Karamu was also a contributor to the Harlem Renaissance, and Langston Hughes roamed the halls.

Reflecting the strength of the Black influence on its development, the Playhouse Settlement was officially renamed Karamu House in 1941. Karamu is a word in the Kiswahili language meaning "a place of joyful gathering." Karamu House had developed a reputation for nurturing black actors having carried on the mission of the Gilpin Players, a black acting troupe whose heyday predated Karamu. Directors such as John Kenley, of the Kenley Players, and John Price, of Musicarnival— a music "tent" theater located in Warrensville Heights, Ohio, a Cleveland suburb — recruited black actors for their professional productions.

In 1931, Langston Hughes, and Zora Neale Hurston were negotiating with the Jelliffes to produce Mule Bone, their two act collaboration, when the two writers "fell out." A series of conversations between the Hughes and Hurston estates, the Ethel Barrymore Theatre presented the world premiere of Mule Bone on Broadway in 1991. Finally, sixty-five years after the production was originally proposed, Karamu House presented Mule Bone (The Bone Of Contention) as the 1996–1997 season finale. Karamu's production, directed by Sarah May, played to standing room only audiences in the Proscenium (Jelliffe) Theatre. The by-line in The Plain Dealer, as the Cleveland theatre season came to its end read: "Karamu returns to Harlem Renaissance status." Critic Marianne Evett shared Karamu's success story as the theatre began to recover from past hardships. The revival Karamu House needed so desperately had arrived. During this time, playwright and two time Emmy nominee Margaret Ford-Taylor held the position of executive director, and Sarah May, Director in Residence.

The Karamu House Theatre was added to the National Register of Historic Places on December 17, 1982. From October 2003 to March 2016, Terrence Spivey served as Karamu's artistic director. Tony F. Sias currently serves as CEO + President, Aseelah Shareef serves as COO + Vice President. In 2017, a major renovation of the facility was undertaken. The architect Robert P. Madison International, Ohio's first African American-owned architectural firm, founded by Cleveland architect Robert P. Madison, lead the 14.5 million dollar renovation. This included a new streetscape, bistro, patio, and enclosed outdoor stage; as well as updates to the Arena Theater, lobby, and dressing rooms.

0 notes

Text

Beginnings: Peter Cushing’s Purley

It’s fair to say that if Peter Cushing was associated with a place outside of the fictional castles and laboratories he inhabited in his many film roles, the first to come to mind would likely be the actor’s final residence of Whitstable on the Kent coast.

The connection is understandable given the public bench there named Cushing’s View in his honour, as well as the local museum housing a permanent exhibit about him and even the local branch of Wetherspoons bearing his name. Yet Cushing was not a Kent man first and foremost. Instead, his early life unfolded in one of the most southern parts of London, and was arguably pivotal to the life of this most genteel and respected of horror’s leading men.

Cushing was born at home on 26 May, 1913 in Godstone Road in Kenley, where London finally dips and recedes into the greenery of Surrey. He was the son of George and Nellie Cushing, the former a successful quantity surveyor from a respectable family, the latter from a working-class background of merchants. The family moved to Dulwich Village for a time, along with Cushing’s older brother George, as World War One enveloped Europe; Desenfans Road was a quiet, leafy street just beyond Dulwich Park.

The family would soon move south again to Purley. The main house they would eventually live in, however, was not a normal building by any means: 32 St James’ Road was a project undertaken by George Cushing, a building designed in line with the very latest Art Deco fashions emerging at the time. With its white gleaming walls and thin windows, the house must have looked like something from the future surrounded by its more typical wood-beam neighbours. The house was finished in 1926 and Cushing spent the remainder of his childhood and school years there, though all was not as neat and precise in the life of the actor as his father’s building.

Cushing was sent to a respected boarding school in Shoreham-by-Sea, but he was irredeemably homesick and so returned to Purley after just one term. Throughout his time at Purley County Secondary School, where he eventually found himself, Cushing was generally ambivalent about his academic learning, with the exception of the arts which he loved. He even enlisted the help of his more academically inclined brother with homework. Encouraged by the school’s physics teacher who ran the dramatic society and organised the school plays, Cushing soon found himself leading most productions, much to the detriment of his wider work. His father was not pleased.

Hoping he would work a steadier job than acting, Cushing Sr helped his son attain a job in the surveyors’ office at Couldson and Purley Urban District Council. He hoped his son’s creative urges could be satiated by time spent in the drawing department. After all, Cushing had often skipped classes in order to paint and make the sets for the school plays. He spent three years plodding along, his little enthusiasm further constrained by a constant reluctance of the department to engage with any of his, likely impractical, ideas for planning.

In the meantime, in a tellingly determined move, he continued acting in the school plays in spite of no longer being a pupil, still at the encouragement of his physics teacher who saw promise in his talents. His life as a draftsman for the council was simply not to be and Cushing soon ventured further into the acting world.

It was not to be an easy ride by any means and would have been understandable if he had given up and continued in his father’s line of work. He began applying for auditions for plays but was more often than not rejected due to a lack of professional experience. His first audition for a scholarship at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama went badly and it required Cushing’s writing an absurd number of letters to the theatre manager in order to be recognised.

Even then, the eventual meeting that led to him being given his first walk-on part and the scholarship was initially organised simply to ask him to stop pestering them. He soon appeared in rep, touring with the Southampton Repertory Company before finally accepting that Hollywood and films were really his aim. For all of his reservations and attempts to steer Cushing towards work for the council, his father did eventually provide one particularly vital aid: he paid for his son’s one-way ticket to America. Even if his roles were slim and his star would not properly align until well into his forties when he returned to working in England, it must have seemed an astonishing gesture at the time.

In spite of the macabre roles, Cushing has always seemed childlike in his awe of fantasy. Living with his parents, I can imagine him with an array of toys conjuring up worlds and learning lines in the futuristic house his father built. His first fiancé, the actor and eventual wife of Jack Hawkins, Doreen Lawrence, broke off their engagement due to his gentle emotional character and his regular inclusion of his parents on their dates.

Many years after his success, the child still remained. A wonderful Pathé film shot when Cushing lived in 9 Hillsleigh Road, Kensington with his wife Helen, looks at the actor’s continued war-gaming hobby, the older Cushing still building worlds in which to explore. His exploration of the fantastical was always carried out with childlike enthusiasm, whether on a bedroom floor in Purley or – thankfully for horror and film fans alike – in film studios around the world.

youtube

The post Beginnings: Peter Cushing’s Purley appeared first on Little White Lies.

source https://lwlies.com/articles/beginnings-peter-cushing-purley-home/

0 notes

Text

Goodbye Route 455... it's been a long, long journey. Too long

There’s more than a touch of an old Morecambe and Wise gag about the extensive changes to 10 bus routes in Croydon and Sutton: ‘TfL has chosen all the right routes, just not the right roads’. By JEREMY CLACKSON, transport correspondent End of the line: the 455 between Wallington and Old Coulsdon, via Purley, will operate for a final time on Mar 1 Significant changes are coming to 10 bus routes…

View On WordPress

#Charles King#Coulsdon#Croydon#Croydon Council#East Surrey Transport Committee#Kenley#Kenley Residents Association#London#London Buses#Neil Garratt#Old Coulsdon#Purley#Purley Hospital#Purley Way#Route 455#South Croydon#St Helier#Sutton#Sutton Council#TfL#Transport for London#Wallington

0 notes

Text

Life-saving first aid lessons, Kenley Memorial Hall, Apr 13

Continue reading Life-saving first aid lessons, Kenley Memorial Hall, Apr 13

View On WordPress

#KENDRA#Kenley#Kenley and District Residents Association#Kenley Memorial Hall#London Ambulance Service

0 notes