#Katsushiro

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Band AU

#samurai 7#sam7#okamoto katsushiro#katsushiro#kyuzo#hayashida heihachi#heihachi#shichiroji#kikuchiyo#digital#art#sketchbook#gorobei and kanbei are producer and manager respectively i just ran out of time and space to draw them

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

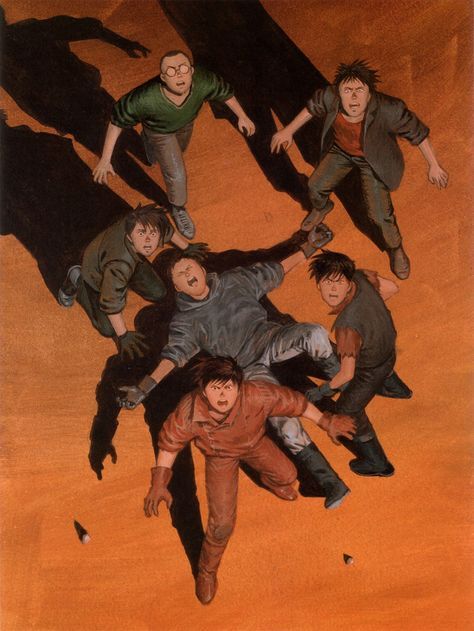

Akira (1988) Katsuhiro Otomo

791 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bungou Stray Dogs S4 || Atsushi Nakajima Episode 11

#bungou stray dogs#fybungousd#dailybungou#bsdedit#bsdgraphics#atsushi nakajima#katsushiro okamoto#bsd4#my gifs#my post

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Colour 24

BG49 Duck blue

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Okamoto Katsushiro / Samurai 7

He’s a teenager in the anime

Name: Okamoto Katsushiro

Age: Teenage

Restrictions: None

#cantheywinthehungergames#hunger games#the hunger games#thg#thg series#samurai 7#sam7#okamoto katsushiro#katsushiro okamoto#poll

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

i invite you over for a casual dinner but instead i actually make you watch the entirety of akira kurosawa's seven samurai in one sitting with me

#and then afterward we have a highly academic discussion about how gay kyuzo kikuchiyo and katsushiro are#i say things

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm starting to get obsessed with this movie, I'm gonna watch it with my mom when I grow up :3

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

tags post

tags post

0 notes

Text

OSAMU TEZUKA’S METROPOLIS:

Futuresque city

Boy befriends android girl

Burn the status quo

youtube

#osamu tezuka#metropolis#random richards#poem#haiku#poetry#haiku poem#poets on tumblr#haiku poetry#haiku form#rintaro#toshio furukawa#Scott weinger#katsushiro otomo#fritz lang#thea von harbou#anime#Youtube

0 notes

Photo

glad I have friends that indulge my stupider ideas

#samurai 7#sam7#anime#cats#hoh boy#katsushiro#gorobei#heihachi#shichiroji#kanbei#kyuzo#kikuchiyo#okamoto katsushiro#katayama gorobei#hayashida heihachi#shimada kanbei#digital#art#sketchbook

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

I had a full boat yesterday, and wasn't able to do yesterday's post. The one I posted this morning for yesterday was Black Milk, by Massive Attack and Liz Fraser. Today's is one of the genre's classics. Dr. Shoji Yamashiro and Geinoh Yamashirogumi gave us 'Kaneda' for the theme to Katsushiro Otomo's adaptation of 'Akira' all the way back in 1988. It's cliche and hyperbole to say nothing was the same for Anime over here in the United States since. It's also entirely true.

And of course, that movie opens with Kaneda and his chooms lighting out into the nighttime in Neo-Tokyo on their bikes for a bit of the old ultraviolence. And as the holographic expanses over them cycle on, Kaneda's guys get into a tussle with an opposing Clown Gang in the streets and ridiculous speeds. And honestly, when you get on your Kusanagi and you're firing down the road at some ridiculous speed of your own; weaving and dodging through traffic that might as well be stationary in comparison, more than one of you are hearing this music in your head. So much CP can name this movie as its direct ancestor. It would be criminal not to include it here.

youtube

#Cyberpunk#Cyberpunk 2077#Cyberpunk 77#CP77#Akira#Motorcycle Scene#Kaneda#Dr. Shoji Yamashiro#Geinoh Yamashirogumi#Katsushiro Otomo#Youtube

0 notes

Photo

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

As freshmen at New York University’s film school, some chums and I had an unusual greeting. “We live on rice gruel!” we would say if we saw one another around campus. “We’ll make do on millet!” was the reply.

This back-and-forth comes from an early scene in Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (1954), a movie somewhat force-fed to us on our first day to teach concepts about the language of cinema such as shot/reverse shot and the fourth wall—conventions that today’s students already have in their blood having played with iPhones before they could walk. Though presented as a literal classroom assignment, Seven Samurai’s appropriation as an inside joke among know-it-all 18-year-olds is proof that watching this landmark of world cinema does not feel like homework. Indeed, revisiting the “good guys with a code facing an unwinnable battle” picture for its 70th anniversary, remastered and appearing in cinemas across North America this summer, reminded me that it’s just as fun now as it ever was.

If one had to chisel a Mount Rushmore of so-called foreign films from the influential midcentury period, surely the image of Toshiro Mifune’s mad swordsman Kikuchiyo from Seven Samurai would be among the four granite faces, right next to the cloaked figure of death from Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957), Marcello Mastroianni with the fedora and whip from Federico Fellini’s self-mythologizing 8½ (1963), and Jean-Pierre Léaud’s truant teen in François Truffaut’s directorial debut The 400 Blows (1959). (For the French nouvelle vague, you could also make the case for Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless, but I’m picking The 400 Blows because this way they all have numbers in the title.)

Though Kurosawa was already a known quantity internationally after the release of Rashomon (1950), a period drama in which several people recall a violent incident differently depending on their point of view, Seven Samurai was both a domestic success and a ripping-enough yarn—swords! archery! horses! mud! gruel!—to engage the rest of the world.

Japanese cinema of the postwar period was initially reluctant to dig into its samurai storytelling heritage, the notion of blind loyalty to feudal lords being understandably less popular at the time. The two most famous Japanese films released just before and after Seven Samurai remain Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story (1953), basically an enormous guilt trip pointed at modernity for letting down their elders, and Ishiro Honda’s Godzilla (1954), a nation’s collective apocalyptic nightmare that somehow mutated into a still thriving merchandise line. Seven Samurai is set in the late 1500s, during the Sengoku period of civil war, a chaotic time that found many of the samurai class without masters. Many of these men became mercenaries, but imagine a story in which some of them (seven, if you will) decided to join forces against impossible odds because it was the righteous thing to do. In revisiting classic Japanese heroism but acknowledging the then-current sentiment, the picture had its rice gruel and ate it too.

The tumultuous setting depicted in the film—the most expensive in Japanese history at the time—no doubt resonated with a Japan that was modernizing rapidly, as did the secondary theme, blurring the lines of a previously clear class system. The highborn Katsushiro (Isao Kimura) falling for the farmer’s daughter Shino (Keiko Tsushima) amid the endless meadows of chrysanthemums, and Mifune’s Kikuchiyo, revealed to be a fraud to the samurai class but one who proves himself in combat, may feel like classic movie characters, but to a postwar Japan in search of a new identity, these transgressions resonated on a much deeper level.

Seven Samurai has a very simple story that perfectly suits its several high-energy set pieces. The 207-minute epic (that’s about 29 minutes per samurai) is set during a time when the countryside is terrorized by bandits who plunder small villages, depleting their harvests and kidnapping women. Already brutalized villagers, aware that they will soon be targeted again, decide to defend themselves by hiring some outside muscle. But how can they afford to pay (see above: “We live on rice gruel!”)? you may wonder. The wise elder who lives inside a mill with a water wheel providing an incessant warlike beat knows the answer: Don’t just find samurai, “find hungry samurai.”

Timid representatives of the village head to town and witness the bravery and creative thinking of Kambei (Takashi Shimura). They convince him to take the gig, and then he assembles his crew. This includes Kyuzo (Seiji Miyaguchi), a cold-as-ice swordsman; Gorobei (Yoshio Inaba), a brilliant tactician; the eager silver-spoon apprentice Katsushiro; and the loose-cannon Kikuchiyo, who, in time, emerges as the real star of the show. (There are two other guys: One is kind of the morale officer, and the other is just Kambei’s pal.) Anyway, if the plot seems familiar, yes, it has been adapted for Western cinema several times, most notably as the gunslinging The Magnificent Seven (both in 1960 and 2016), sci-fi romp Battle Beyond the Stars (1980), and, if you want to stretch it, the dopey comedy Three Amigos! (1986) and the Pixar cartoon A Bug’s Life (1998). Beyond that, a great many standard cinematic tropes have their roots in this movie.

Most obvious is the first act of the film, in which Kambei builds up the team. There’s no need to overly intellectualize it; it’s just fun to watch him size up potential comrades, test them out, and then make his appeal. There’s also a wonderful moment in which we think we’ve got a new addition but the samurai in question shrugs off the approach when he hears there’s no money or fame in the job. Should Disney ever purchase Toho Studios, we can maybe expect a limited streaming series to find out whatever happened to that guy. Anyway, every movie from The Dirty Dozen to The Blues Brothers to The Right Stuff to Ocean’s Eleven to School of Rock owes a lot to Seven Samurai.

Another influential development is how the villagers (and we in the audience) first meet Kambei. There is some tumult in town as a thief has kidnapped a child and barricaded himself inside a building. Kambei cuts off his hair (a very big deal for a samurai), poses as a monk, and then, after a series of badass moves, rescues the child and kills the baddie in slow motion. Introducing the hero through a mini-mission before we get to the real mission is now so common (think every single James Bond movie) that it’s funny to think it had to originate somewhere.

Most of the so-called movie brats of New Hollywood revered Kurosawa, but none so much as George Lucas, who would later use his clout to help the Japanese director secure funding for his expansive project Kagemusha. While there are more one-to-one alignments between other Kurosawa films and Star Wars (most famously, the original R2-D2 and C-3PO in 1958’s The Hidden Fortress, two comic-relief peasants tagging along on an adventure to save a princess), there’s still a lot in Seven Samurai that made it to the galaxy far, far away.

For starters, there are those wipe transitions between scenes. And then who is the wise elder hunched in the dark speaking truncated wisdom if not The Empire Strikes Back’s version of Yoda? The romance between Katsushiro and Shino is something like a Han Solo-Princess Leia dynamic in reverse, as well. On a technical level, though, one can point to the rising action of the final battle. While there is no exploding Death Star, Kurosawa, who deployed multiple cameras shooting concurrently, cuts not just between different angles of the same fight but between several skirmishes all building to the final thrilling, albeit pyrrhic, victory.

Most striking for its time—and still fiery today—is Seven Samurai’s most impressive element, Mifune. An explosive performer by any standard, let alone the typically taciturn style seen in Japanese movies of the period, Mifune is like a cross between Stanley Kowalski and Woody Woodpecker: muscular one minute, flamboyantly loosey-goosey the next. Like Marlon Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire, Mifune dominates every scene he is in with an unpredictable magnetism. (Though never stated as such, John Belushi’s famous samurai character on Saturday Night Live is basically an exaggerated version of Mifune.) Kikuchiyo is a drunkard and a brute but also silly and, when necessary, fragile. His scene rescuing an infant from a burning building is probably the best thing in the entire movie. Any other actor could have played the part as merely loud and annoying, but Mifune turns the role into something sensuous, mesmerizing, and sui generis. There are many reasons we’re still talking about this movie 70 years later, and the biggest reason of all is him.

The anniversary of the picture means its first remastering to 4K and a significant release in North America. (Not just New York and Los Angeles but places including Akron, Ohio; Paducah, Kentucky; and Kitchener, Ontario—here’s the full list.) With a 15-minute intermission plus a little time to buy popcorn, we’re talking about a four-hour commitment at the movie theater. With today’s limited attention span and hectic schedules, programming this film may seem like going up against impossible odds. Hopefully, there are enough people out there still ready to heed the call and do what’s right, no matter the cost.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seven Samurai, as a movie, wasnt about Seven Samurais doing cool Samurai Shit. It was a story that dealt with topics of class, war, generation and the idea of heroism.

The interactions between the characters wasnt mere banter, it reflected plenty of things about each of them and the relationship each had.

The character of Katsushiro, for example, Starts as a naive young kid who idealizes being a Samurai, but by the end, as he matures, he becomes saddened by the reality of combat. likewise his romance with the local village girl is tragic, because they can never be together due to their class differences.

Meanwhile, the character of Kikuchiyo was that of a farmer who was faking being a Samurai. But by the end, despite his antics, he dies a true Samurai's death, to the point nobody can deny this farmer is no warrior.

And in the end, the final note is sad. because while they were victorious, our heroes lost their friends in the process. which leads to them sadly comment that the villagers won, but they lost.

And it was not for some greater good. it was not a battle to save the world, or to rescue a princess. it was to defend a "mere" village. A village that is not important in the grand scheme of things.

And to ignore that part, to ignore that the core of Seven Samurai is having these distinct characters with distinct personalities interacting and clashing and changing as people as they fight a battle that matter to no one but a bunch of villagers, what you end up with is with a hollow product.

46 notes

·

View notes

Note

So your crustaceans are named after chefs. What are some other noteworthy names for the aquarium residents?

Well, we also have:

Our Pyukumuku which are all named after different kinds of beans- Pinto, Java, Lima, Kidney, Navy, Black, and Lentil

Mama Feraligatr's name is Pancake. You'll never guess why (its because she's flat)

Her hatchlings are named Maple, Butter, Sugar, Choco, and Nanab. They're the Breakfast Bunch :)

Papa Feraligatr's name is Offler. He's an old man

One of the hatchling specialists is a big film nerd and our Samurott had seven eggs, so the Oshawott pups are named Kanbei, Gorobei, Shichiroji, Kyuzo, Hayashida, Katsushiro, and Kikuchikyo. Apparently the guys from the movie they're named after is a classic?? idk i havent seen it

There was a LOT of debate when we almost named the Cloyster 'Yonic'. We were so close

One of our Quagsires is named Bub. idk why that gets me so good sometimes I'll just be minding my business and I'll remember Bub and his little :] face and I'll just laugh REALLY hard. It's SUCH a good name for a Quagsire

#irl pokemon#pokemon#pokemon irl#water pokemon#water type#pyukumuku#feraligatr#totodile#oshawott#quagsire#cloyster#asks#((ooc: I've seen Seven Samurai. it slaps. you should watch it too))

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seven Samurai

I’ve heard of Seven Samurai before, but I haven’t had the chance to watch it myself. Now I understand what all the hype is about. It depicts a great epic of a ronin who attempts to protect the lives of farmers who are under attack by a bunch of mountain bandits. Set in the Sengoku period (around 1586), where samurai were still around and guns were a novelty at the time, it shows a lot of the adversity the people went through living at the time. On the surface, it seems like a fairly simple story with a conflict that is one dimensional, the titular seven samurai defending the town that they nobly volunteered to defend, but Kurosawa (along with his team) wanted to show much more than that to the viewers.

It starts with a very stylistic introduction of the actors and writers that worked on it with a tilted script of their names, along with drums that set the scene. The movie then tells a quick backstory with a fade cut into the marching of the bandits that goes along with the beat of the drums. From the beginning, Kurosawa masterfully depicted the differences between the country people and the “city” folk as we were easily able to tell who was who. I also noticed a lot of close-up shots of the men, especially the old man when they were discussing what to do. I assumed that depicted his importance, but also the struggle that he understood would come to be. The old man had this happen to him before, so he knew what needed to happen for the village to survive.

From those points, I was truly able to understand what the old man was talking about, as well as the ronin’s (Shimada) point of view, especially at the end. Shimada states, “In the end, we lost this battle too,” with a forlorn look on his face. “Victory” would have been achievable if they had not lost one of their comrades, but even if they had lost one person, they would have still lost, especially in the old ronin’s eyes. That point made in the movie made me really appreciate the underlying points in the movie. We think that the main conflict is between the bandits vs. the farmers and the samurai, but to me it was about the ronin finding a place to belong, personified the most by Kikuchiyo. The farmers had a place of belonging, but the ronin did not. Like I said earlier, Kikuchiyo especially impacted Shimada the most, because the same thing happened to him but he wanted to change his status and so he became a samurai. In addition to Kikuchiyo, I also viewed Rikichi as one of the few peasants that came to understand both sides. He guided them along their journey and even though it was fueled by revenge, he still wanted to help. The shot I took was of Kikuchiyo shown almost a t the angle of a wild animal that was trying to fit in, and ultimately he does with the samurai.

Some points that I saw but didn’t know how to fit in smoothly, were the societal expectations of peasant classes versus the samurais (as well as the higher ups). When Manzo was trying to protect his daughter by cutting her hair, he did not consider her feelings at all, which I felt was normal for many people at the time, viewing women as more commodities than people themselves

Katsushiro and the girl in the flower fields representing the innocence of war

Katsushiro waits for them in the flowers (again) while Kyuzo and Kikuchiyo are in a higher place which could represent their positions, as well as experience

I really liked this shot that showed the wear that it had on the old ronins (the cost of war). Both of them are very tired, while they let Katsushiro doze off because he is younger

4 notes

·

View notes