#Kant's Synthetic A Priori

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Philosophy of Arithmetic

The philosophy of arithmetic examines the foundational, conceptual, and metaphysical aspects of arithmetic, which is the branch of mathematics concerned with numbers and the basic operations on them, such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. Philosophers of arithmetic explore questions related to the nature of numbers, the existence of mathematical objects, the truth of arithmetic propositions, and how arithmetic relates to human cognition and the physical world.

Key Concepts:

The Nature of Numbers:

Platonism: Platonists argue that numbers exist as abstract, timeless entities in a separate realm of reality. According to this view, when we perform arithmetic, we are discovering truths about this independent mathematical world.

Nominalism: Nominalists deny the existence of abstract entities like numbers, suggesting that arithmetic is a human invention, with numbers serving as names or labels for collections of objects.

Constructivism: Constructivists hold that numbers and arithmetic truths are constructed by the mind or through social and linguistic practices. They emphasize the role of mental or practical activities in the creation of arithmetic systems.

Arithmetic and Logic:

Logicism: Logicism is the view that arithmetic is reducible to pure logic. This was famously defended by philosophers like Gottlob Frege and Bertrand Russell, who attempted to show that all arithmetic truths could be derived from logical principles.

Formalism: In formalism, arithmetic is seen as a formal system, a game with symbols governed by rules. Formalists argue that the truth of arithmetic propositions is based on internal consistency rather than any external reference to numbers or reality.

Intuitionism: Intuitionists, such as L.E.J. Brouwer, argue that arithmetic is based on human intuition and the mental construction of numbers. They reject the notion that arithmetic truths exist independently of the human mind.

Arithmetic Truths:

A Priori Knowledge: Many philosophers, including Immanuel Kant, have argued that arithmetic truths are known a priori, meaning they are knowable through reason alone and do not depend on experience.

Empiricism: Some philosophers, such as John Stuart Mill, have argued that arithmetic is based on empirical observation and abstraction from the physical world. According to this view, arithmetic truths are generalized from our experience with counting physical objects.

Frege's Criticism of Empiricism: Frege rejected the empiricist view, arguing that arithmetic truths are universal and necessary, which cannot be derived from contingent sensory experiences.

The Foundations of Arithmetic:

Frege's Foundations: In his work "The Foundations of Arithmetic," Frege sought to provide a rigorous logical foundation for arithmetic, arguing that numbers are objective and that arithmetic truths are analytic, meaning they are true by definition and based on logical principles.

Russell's Paradox: Bertrand Russell's discovery of a paradox in Frege's system led to questions about the logical consistency of arithmetic and spurred the development of set theory as a new foundation for mathematics.

Arithmetic and Set Theory:

Set-Theoretic Foundations: Modern arithmetic is often grounded in set theory, where numbers are defined as sets. For example, the number 1 can be defined as the set containing the empty set, and the number 2 as the set containing the set of the empty set. This approach raises philosophical questions about whether numbers are truly reducible to sets and what this means for the nature of arithmetic.

Infinity in Arithmetic:

The Infinite: Arithmetic raises questions about the nature of infinity, particularly in the context of number theory. Is infinity a real concept, or is it merely a useful abstraction? The introduction of infinite numbers and the concept of limits in calculus have expanded these questions to new mathematical areas.

Peano Arithmetic: Peano's axioms formalize the arithmetic of natural numbers, raising questions about the nature of induction and the extent to which the system can account for all arithmetic truths, particularly regarding the treatment of infinite sets or sequences.

The Ontology of Arithmetic:

Realism vs. Anti-Realism: Realists believe that numbers and arithmetic truths exist independently of human thought, while anti-realists, such as fictionalists, argue that numbers are useful fictions that help us describe patterns but do not exist independently.

Mathematical Structuralism: Structuralists argue that numbers do not exist as independent objects but only as positions within a structure. For example, the number 2 has no meaning outside of its relation to other numbers (like 1 and 3) within the system of natural numbers.

Cognitive Foundations of Arithmetic:

Psychological Approaches: Some philosophers and cognitive scientists explore how humans develop arithmetic abilities, considering whether arithmetic is innate or learned and how it relates to our cognitive faculties for counting and abstraction.

Embodied Arithmetic: Some theories propose that arithmetic concepts are grounded in physical and bodily experiences, such as counting on fingers or moving objects, challenging the purely abstract view of arithmetic.

Arithmetic in Other Cultures:

Cultural Variability: Different cultures have developed distinct systems of arithmetic, which raises philosophical questions about the universality of arithmetic truths. Is arithmetic a universal language, or are there culturally specific ways of understanding and manipulating numbers?

Historical and Philosophical Insights:

Aristotle and Number as Quantity: Aristotle considered numbers as abstract quantities and explored their relationship to other categories of being. His ideas laid the groundwork for later philosophical reflections on the nature of number and arithmetic.

Leibniz and Binary Arithmetic: Leibniz's work on binary arithmetic (the foundation of modern computing) reflected his belief that arithmetic is deeply tied to logic and that numerical operations can represent fundamental truths about reality.

Kant's Synthetic A Priori: Immanuel Kant argued that arithmetic propositions, such as "7 + 5 = 12," are synthetic a priori, meaning that they are both informative about the world and knowable through reason alone. This idea contrasts with the empiricist view that arithmetic is derived from experience.

Frege and the Logicization of Arithmetic: Frege’s attempt to reduce arithmetic to logic in his Grundgesetze der Arithmetik (Basic Laws of Arithmetic) was a foundational project for 20th-century philosophy of mathematics. Although his project was undermined by Russell’s paradox, it set the stage for later developments in the philosophy of mathematics, including set theory and formal systems.

The philosophy of arithmetic engages with fundamental questions about the nature of numbers, the existence of arithmetic truths, and the relationship between arithmetic and logic. It explores different perspectives on how we understand and apply arithmetic, whether it is an invention of the human mind, a discovery of abstract realities, or a formal system of rules. Through the works of philosophers like Frege, Kant, and Leibniz, arithmetic has become a rich field of philosophical inquiry, raising profound questions about the foundations of mathematics, knowledge, and cognition.

#philosophy#knowledge#epistemology#learning#education#chatgpt#ontology#metaphysics#Arithmetic#Philosophy of Mathematics#Number Theory#Logicism#Platonism vs. Nominalism#Formalism#Constructivism#Set Theory#Frege#Kant's Synthetic A Priori#Cognitive Arithmetic

1 note

·

View note

Text

Delving into Kantian Philosophy: A Review of "The Critique of Pure Reason" by Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant's "The Critique of Pure Reason" stands as one of the most influential and enduring works in the history of philosophy, reshaping the landscape of metaphysics, epistemology, and the philosophy of mind. Published in 1781, this monumental treatise seeks to provide a comprehensive account of the nature, scope, and limits of human knowledge, offering profound insights into the nature of reality, the structure of the mind, and the conditions of possibility for knowledge.

At the heart of "The Critique of Pure Reason" is Kant's revolutionary concept of transcendental idealism, which posits that the mind plays an active role in shaping our experience of the world. Kant argues that the mind imposes certain fundamental concepts and categories—such as space, time, and causality—on our sensory perceptions, organizing them into a coherent and intelligible framework. Through his rigorous analysis, Kant seeks to uncover the a priori conditions that make experience possible, shedding light on the fundamental structures of human cognition.

One of the key themes of "The Critique of Pure Reason" is Kant's distinction between phenomena and noumena, or appearances and things-in-themselves. Kant argues that while we can only know phenomena as they appear to us through the filter of our cognitive faculties, there exists a realm of noumena that lies beyond the reach of human knowledge. This distinction has profound implications for Kant's philosophy, shaping his views on the limits of human understanding and the nature of metaphysical inquiry.

Moreover, "The Critique of Pure Reason" is notable for its meticulous analysis of the nature of space, time, and causality, which Kant identifies as the fundamental categories of human thought. Kant argues that these categories are not derived from experience, but rather constitute the necessary framework through which we interpret our sensory perceptions. By elucidating the synthetic a priori nature of these categories, Kant lays the groundwork for his transcendental idealism and challenges traditional empiricist and rationalist accounts of knowledge.

In addition to its groundbreaking philosophical insights, "The Critique of Pure Reason" is also celebrated for its rigorous methodology and systematic approach to philosophical inquiry. Kant's meticulous argumentation, intricate terminology, and careful exposition of concepts make "The Critique of Pure Reason" a challenging but rewarding read for scholars and philosophers alike. Kant's influence extends far beyond the boundaries of philosophy, shaping the development of disciplines such as psychology, physics, and linguistics, and leaving an indelible mark on the intellectual landscape of the modern world.

In conclusion, "The Critique of Pure Reason" by Immanuel Kant is a towering achievement in the history of philosophy, offering profound insights into the nature of human knowledge, the structure of the mind, and the limits of metaphysical inquiry. Kant's rigorous analysis, groundbreaking concepts, and systematic approach to philosophical inquiry make "The Critique of Pure Reason" a timeless classic that continues to inspire and challenge readers with its depth, complexity, and intellectual rigor.

Immanuel Kant's "The Critique of Pure Reason" is available in Amazon in paperback 24.99$ and hardcover 31.99$ editions.

Number of pages: 516

Language: English

Rating: 10/10

Link of the book!

Review By: King's Cat

#Immanuel Kant#Critique of Pure Reason#Transcendental idealism#Phenomena#Noumena#A priori knowledge#Metaphysics#Epistemology#Synthetic a priori judgments#Space#Time#Causality#Categories of understanding#Rationalism#Empiricism#Skepticism#Transcendental deduction#Transcendental aesthetics#Transcendental logic#Analytic judgments#Synthetic judgments#Appearances#Things-in-themselves#Transcendental unity of apperception#Unity of consciousness#Schematism#Idealism#Rationalist philosophy#Epistemological inquiry#Metaphysical inquiry

0 notes

Text

Delving into Kantian Philosophy: A Review of "The Critique of Pure Reason" by Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant's "The Critique of Pure Reason" stands as one of the most influential and enduring works in the history of philosophy, reshaping the landscape of metaphysics, epistemology, and the philosophy of mind. Published in 1781, this monumental treatise seeks to provide a comprehensive account of the nature, scope, and limits of human knowledge, offering profound insights into the nature of reality, the structure of the mind, and the conditions of possibility for knowledge.

At the heart of "The Critique of Pure Reason" is Kant's revolutionary concept of transcendental idealism, which posits that the mind plays an active role in shaping our experience of the world. Kant argues that the mind imposes certain fundamental concepts and categories—such as space, time, and causality—on our sensory perceptions, organizing them into a coherent and intelligible framework. Through his rigorous analysis, Kant seeks to uncover the a priori conditions that make experience possible, shedding light on the fundamental structures of human cognition.

One of the key themes of "The Critique of Pure Reason" is Kant's distinction between phenomena and noumena, or appearances and things-in-themselves. Kant argues that while we can only know phenomena as they appear to us through the filter of our cognitive faculties, there exists a realm of noumena that lies beyond the reach of human knowledge. This distinction has profound implications for Kant's philosophy, shaping his views on the limits of human understanding and the nature of metaphysical inquiry.

Moreover, "The Critique of Pure Reason" is notable for its meticulous analysis of the nature of space, time, and causality, which Kant identifies as the fundamental categories of human thought. Kant argues that these categories are not derived from experience, but rather constitute the necessary framework through which we interpret our sensory perceptions. By elucidating the synthetic a priori nature of these categories, Kant lays the groundwork for his transcendental idealism and challenges traditional empiricist and rationalist accounts of knowledge.

In addition to its groundbreaking philosophical insights, "The Critique of Pure Reason" is also celebrated for its rigorous methodology and systematic approach to philosophical inquiry. Kant's meticulous argumentation, intricate terminology, and careful exposition of concepts make "The Critique of Pure Reason" a challenging but rewarding read for scholars and philosophers alike. Kant's influence extends far beyond the boundaries of philosophy, shaping the development of disciplines such as psychology, physics, and linguistics, and leaving an indelible mark on the intellectual landscape of the modern world.

In conclusion, "The Critique of Pure Reason" by Immanuel Kant is a towering achievement in the history of philosophy, offering profound insights into the nature of human knowledge, the structure of the mind, and the limits of metaphysical inquiry. Kant's rigorous analysis, groundbreaking concepts, and systematic approach to philosophical inquiry make "The Critique of Pure Reason" a timeless classic that continues to inspire and challenge readers with its depth, complexity, and intellectual rigor.

Immanuel Kant's "The Critique of Pure Reason" is available in Amazon in paperback 24.99$ and hardcover 31.99$ editions.

Number of pages: 516

Language: English

Rating: 10/10

Link of the book!

Review By: King's Cat

#Immanuel Kant#Critique of Pure Reason#Transcendental idealism#Phenomena#Noumena#A priori knowledge#Metaphysics#Epistemology#Synthetic a priori judgments#Space#Time#Causality#Categories of understanding#Rationalism#Empiricism#Skepticism#Transcendental deduction#Transcendental aesthetics#Transcendental logic#Analytic judgments#Synthetic judgments#Appearances#Things-in-themselves#Transcendental unity of apperception#Unity of consciousness#Schematism#Idealism#Rationalist philosophy#Epistemological inquiry#Metaphysical inquiry

1 note

·

View note

Text

7 November 2023,

Reichenbach should have written a paper on biomolecular topology ~ 🤔

#tagitables#c'mon this field is rad !!#topology#philosophy#mathematics#physics#synthetic a priori#i kant even ..#it could even be synthetic a posteriori#who knows

1 note

·

View note

Text

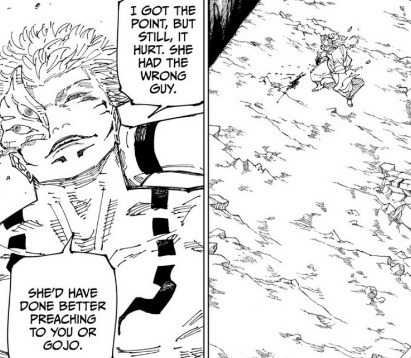

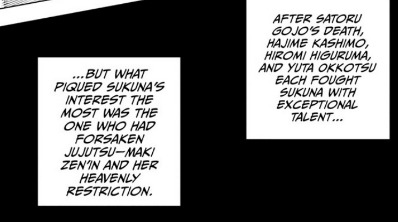

Maki Zen'in vs. Ryomen Sukuna

The past two weeks Maki has faced off against Sukuna. While it seems that Maki and Sukuna's face-off has followed the traditional formula of every individual Sukuna has squared up against so far. That being Sukuna fights them trying to bring out their best, praises them before swiftly defeating them. It's followed the formula so far, with Gojo, Kashimo, Higuruma, and Yuta. Yuta surveys their "taste" as unique sorcerers, and then quickly consumes them.

However, I am going to argue that there's a reason Sukuna takes a special interest in Maki that differs from Gojo Kashimo, Higuruma and Yuta and it's because the two of them foil each other.

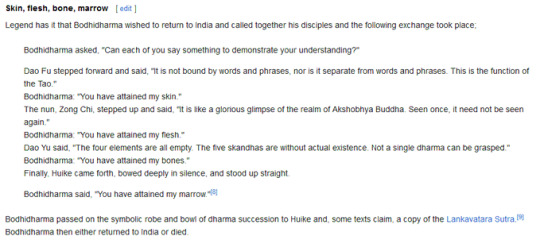

1. Skin and Blood, Bone and Marrow

To badly quote Kant, and Johane Fichte thesis and anti-thesis are both necessary in order to make a statement.

Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason (1781) created the thesis / antithesis dyad, within two statements.

Thesis: "The world had a beginning in time, and is limited in regars to space."

Antithesis: "The world has no beginning and no limits in space, but is infinite, in respect to both time and space."

Fichte turned this dyad into a triad. A set of two contradictory ideas that is resolved with a third statement, synthesis. In order to make of synthesize a new idea, thesis and anti-thesis must meet first.

Are synthetic judgements a priori (before / precending) possible?

No synthesis is possible without a preceding anti-thesis . As little as antithesis without synthesis, or synthesis without anti-thesis, is possible; just as both cannot be born without thesis.

In other words no idea cannot exist without the opposite idea, and no new statements / judgement can be made without exploring these two ideas in opposition to one another.

I spent so much time explaining this philosophical concept because fights in Jujutsu Kaisen aren't just excuses for Akutami Gege to add more elaborate rules to the power system, and give the power-scaling bros more material to argue about. They are a clash of ideals between the two characters fighting, oftentimes with both characters embodying opposite philosophies. At this point it's not subtext, but literally text, Sukuna calls fights a clash of ideals.

Sukuna is not just fighting to physically conquer Yuji, at this point he wants to win in a clash of ideas to, he wants to disprove the ideals Yuji carries in his heart and all that he represents.

Mahito too, all the way back in Shibuya, called his fight with Yuji a clash of truths, rather than the fight between good and evil that Yuji imagined it to be.

Thesis and Anti-thesis are both necessary to make a statement. Yuji cannot prove his ideals to be true, without clashing with Sukuna first, and the same for Sukuna, Sukuna can no longer disprove Yuji's ideals as false without recognizing his ideals and fighting them head on.

There's a statement on twitter I want to steal that summarizes the matchup of every mini-arc in the Sukuna fighting arc so far.

To summarize Lmfalolawholebunchanumbers point, Mahito and Sukuna acting as antagonists challenge the ideals of the protagonists, but while Mahito represents the reverse of humanity's ideals, Sukuna is against the concept of hodling onto any consistent ideology himself. Sukuna in fact believes that all the ideals of the sorcerers that challenged him in the past were false and flimsy, and is troubled by the fact that Yuji holds onto his ideals no matter what.

I already somewhat explored this in this meta, Sukuna's Anti-Enlightement. Where I argue that Sukuna's ideals resemble nihilism, but even then I wouldn't label Sukuna a nihilist because Nihilism is still a set of beliefs and Sukuna doesn't seem to hold onto any consistent ideology or belief system at all. Trying to assign any human branch of thought or motivation to Sukuna doesn't quite work, because Sukuna's point of view isn't one of a human, but more like an inhuman curse, or even a deity. In other words a calamity.

"Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster. And if you gaze long enough into an abyss, the abyss will gaze back into you.” Beyond Good and Evil Part IV Frederick Nietzsche

Nietzsche used the abyss as a metaphor to summarize the unknowable psychological complexity of human beings. You stare at the abyss trying to comprehend it. Which means when facing the abyss, the abyss forms in your mind. Anyone who tries to understand humans must face the fact they are incomprehensible. Anyone who tries to create some meaning to life must confront the fact that the world is so ridiculously overcomplicated and random it's impossible for the human mind to fully comprehend.

The abyss as it exists is a place of danger where it's easy to lose sight of your search for meaning, or even yourself, but in order to grow you have to confront the deepest, darkest part

Anyone who tries searching for the truth, risks confronting the idea that they may be wrong, risks questioning their values, risks confronting the fact that what they believed meaningful might have no meaning at all - and therefore the abyss widens inside of them, they might abandon idealism all together.

Anyway, enough boring philosophy more or less every single person who fights Sukuna risks having their ideas feel false. Or to paraphrase the twitter user I quoted above, most of the characters that try projecting their own human ideals onto Sukuna, find not only do they misunderstand Sukuna entirely, but Sukuna doesn't care about their ideals and disproves them.

Gojo and Kashimo (and before them Yorozu) all try to fight Sukuna, believing they could make Sukuna understand them and understand Sukuna in turn only to find they were misreading Sukuna entirely.

Gojo makes a big deal of trying to bring out Sukuna's best to prove that Sukuna is not alone standing on the top, only to be met with Sukuna basically going "I don't really care."

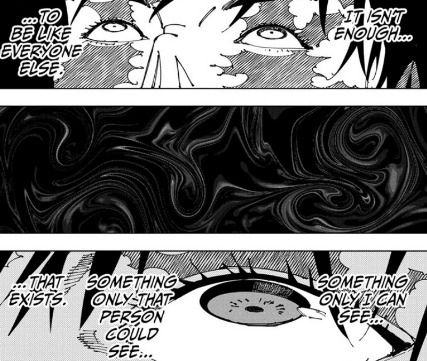

When you confront the abyss, the abyss opens up inside of yourself and your ideas may prove to be false. No one who's faced Sukuna so far, has been able to conquer that abyss, in fact Sukuna keeps rendering their ideals to be false. Perhaps because they are just projecting ideas onto the abyss, looking at Sukuna instead of looking at the abyss inside of themselves.

They want something from Sukuna that Sukuna can't give them, they're looking externally for Sukuna to give them easy answers instead of looking internally. Not one of them is able to form a new idea or make a statement because they're not willing to confront anti-thesis.

The exception to this pattern so far is Maki. There's a reason I've been hammering on about the abyss so much, it's because in this most recent chapter Sukuna calls Maki "a true void."

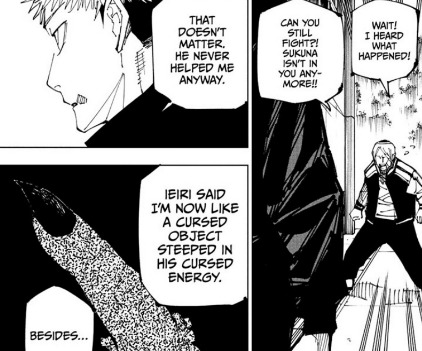

In one sense, there's the technical power system reason why he calls Maki a void. Maki is someone who gave up all cursed energy in order to strengthen her physical body, whereas in comparison Yuji who also mainly fights with his body and super strength, but unlike Maki, Yuji hasn't broken away from cursed energy and is instead soaked in Sukuna's cursed energy.

However, not only has Maki cast off cursed energy, unlike Yuji who has suppressed his own identity to become a cog in favor of his ideal of having a role and supporting other people, Maki has let go of the idea of protecting others and instead focused entirely on the idea of improving her own strength.

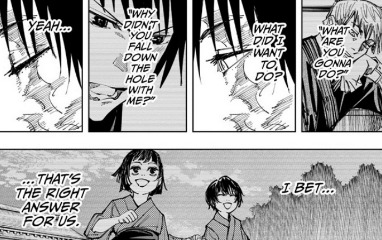

Though, not entirely by choice as Mai sacrificed herself, but Maki's awakening and becoming of herself happened when she let go of Mai, and protecting Mai or reforming the Zen'in for Mai's sake. Not only did Mai take cursed energy with her when she died allowing Maki to break free of cursed energy, but she also let go of her ideal of protecting Mai. Losing her cursed energy went hand in hand with losing her "goal" and almost immediately afterwards she loses her goal of trying to prove herself to the Zen'in or become clan head and just exterminates them entirely.

Everything Maki lived for is gone, so what does Maki live for now? Herself mainly, and the concept of total freedom that comes with no longer tying yourself to others.

In that way, I'd say that Maki almost resembles Sukuna the most, because if Sukuna represents the void that others must confront Maki is the only character that has opened up the void inside of herself. As Sukuna said unlike Yuji who's half-assed in his idealism, Maki's shaved away everything and is contemplatng the void. Almost to reflect this, Gege's done away with most of Maki's internal narration and most of her internal dialogue is focused on either how to win, and how to bring out the fullest of her abilities.

Maki's opened up and contemplated the void inside herself, and in that way she's done away with self-doubt like most of the characters are facing, she's not projecting her anxieties onto Sukuna or wishing for him to answer or resolve her identity crisis like Gojo and Kashimo. She doesn't even have an identity crisis.

In fact, Maki and Sukuna resemble each other so much by both having a void inside of them it makes me wonder if Twin Theory is true that Sukuna also achieved his perfection in Jujutsu by either fusing with his twin in Uterus or cannibalizing his twin somehow.

Even in the fight itself, Maki's the one who's most laser focused on winning, whereas Yuji and Yuta's strategies fail because they're too concerned with saving Megumi who himself at the moment does not wish to be saved. (Saving Megumi is a good thing though, I'm just making a point that Maki much like Sukuna only sees herself winning the fight and prioritizes that above everything else. It's not like she's against saving Megumi either she didn't argue against Yuta and Yuji taking a shot at it). It's just she's the only one who like Sukuna only sees the fight in front of her and doesn't worry about other people. She's laser focused on the win is what I'm saying).

I don't think it's just the fact that Maki has cast away cursed energy that's drawn Sukuna's attention, but the fact that while she represents his anti-thesis focusing on only strengthening the human body, they also share many similarities between them.

They're both the void.

Sukuna even says that Maki's existence denies Jujutsu itself.

Sukuna says that Maki is the only person who's forced him to have a role, and in a way that's true, because by denying Jujutsu, she represents the void that Sukuna has to contemplate now. In a way she's played an uno-reverse card to Sukuna's philosophy of revolving his entire life around strengthening Jujutsu and being the height of Jujutsu.

Sukuna now has to prove Jujutsu's superiority and contemplate the fact that is ideal might in fact be wrong.

Sukuna and Maki both represent the ideal of what one can achieve in the pursuit of strengthening the body, versus strengthening Jujutsu, Hajime even comments that Sukuna's body is absolute perfection.

Not only that, but they both represent the opposing philosophies established by Kenjaku and Yuki, Kenjaku sees the future evolution of humanity as optimizing cursed energy, and Yuki envisions a future of breaking away from cursed energy entirely and even namedropped Toji and Maki both as examples of those ideals.

There's a reason that Gojo is troubled by Toji and remembers his loss to Toji years after the fact, Toji deeply troubles Gojo not because he beat him in a fight and caught him off guard but also because his existence challenged everything Gojo believed to be true.

Gojo is the first inheritor of the six-eyes, and Limitless in hundreds of years, he exists solely for Jujutsu as Nanami said, he was also someone who was arrogant at seventeen and was handed everything at birth, who has always been held up on a pedestal by Jujutsu Society. Yet the only person who seriously challenged Gojo and forced him to evolve before Sukuna rolled around was Toji, someone who is the scapegoat of Jujutsu Society, and who is looked down upon by the the three clans. Suddenly, the inherent superiority that Gojo believed in, all the things he thought made him great b/c he was the peak of the Jujutsu world was called into question if a mere monkey could challenge him.

Toji too, stuck around and fought Gojo because he felt a pressing need to disprove the philosophies and ideals that Gojo represented. However, Toji in this fight lost because he succumbed to the void.

He deviated away from his set of ideals and fell prey to his inferiority complex rather than staying true to himself in face of the void.

Gojo's enlightenment itself comes from facing the void that is Toji Zen'in, and then conquering that void by conquering his own biases against Toji that made him let his guard down. Yet, his defeat against Sukuna comes from the fact that he couldn't conquer the void, he couldn't find his own answers instead relying on Sukuna for an answer and because of that Sukuna reduced him back to a human being again with the world cutting slash that cut through the infinity.

In other words in just two chapters Maki vs. Sukuna have embodied a philosophical battle that has been raging in Jujutsu Kaisen since basically Hidden Inventory, and maybe even the beginning of the manga itself and it is what do your ideals, the ideas you live for mean in face of the void / death. Are they worth holding onto, can you create a synthesis from confronting and overcoming your antithesis, or will you too succumb to the meaninglessness that Sukuna represents?

How do you find meaning in a world where death is random, where anyone can die at any moment, a world that is inherently unfair where good things happen to bad people, and selfish monsters like Sukuna get whatever they want who win because they are selfish and step all over people and take what they want.

Confronting Sukuna means confronting the fact that the world may be empty, and we may all be just killing time until we die.

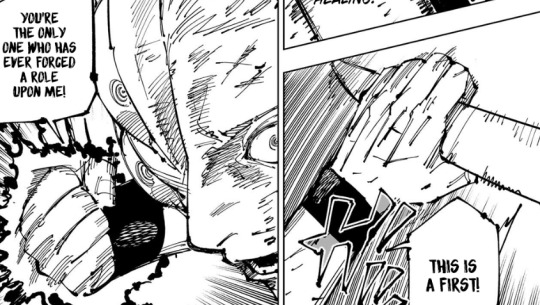

The lines skin and blood, bone and marrow which is what Sukuna uses to refer to the source of is strength (Jujutsu) and the source of Maki's strength (the physical body) are a reference to Bodirahma asking his disciples to understand his teachings.

"You have attained my skin. You have attained my flesh. You have attained my bones. You have attained my marrow."

In other words neither Sukuna and Maki are entirely right, the true understanding comes not from Jujutsu, or the Body, but from both, from skin, flesh, bones and marrow.

In other words, a statement requires thesis and anti-thesis. It's not Maki and Sukuna that are right, and something can be learned from the clash of their ideals.

What I'm saying is basically that JUJUTSU KAISEN is a story with THEMES and I love it.

#maki zenin#ryomen sukuna#yuji itadori#satoru gojo#jjk meta#sukuna#maki zen'in#jujutsu kaisen meta#jujutsu kaisen theory

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

… Carnap, as the fragment below makes evident, was not ultimately a utilitarian or even, perhaps, a consequentialist.

… What the present document makes evident, however, is that he saw inductive value functions, defined by axioms of induction and the choice of an inductive method, as partial value functions, i.e. as guiding choices only over a restricted range of an individual’s (or a society’s) overall priorities.

Opinions will differ about how to characterize the view Carnap sketches. … Still, it is worth noting that Carnap himself rejects a certain kind of consequentialism in this document:

Assume X is perfectly rational at time t and chooses action a in AX. Then it is nonetheless still possible for a not to be an optimum with respect to VX [X’s comprehensive value function]. It could be that an action a' is better than a with respect to VX, due to certain circumstances not known to X at the time of the action. It could even be that the objectively better, i.e. more successful action a' would not be rational for X. As emphasized elsewhere (§[26.IV]), rationality is not to be determined by success. (p. [10])

Carnap refers here to the passages from his 1963 replies regarding the use of experience in the choice of axioms for inductive logic, and of inductive methods, so as to ensure that the choices they lead to are rational. Here the analogy between the partial value functions bearing on the choice of inductive axioms and methods, on the one hand, and comprehensive or moral value functions on the other, becomes explicit, with respect to the relevance of experience to the respective choices. The analogy has limits; while instrumental rationality may constrain substantive (moral) rationality, in this view, it does not determine it; the “purely valuational” criteria Carnap invokes (p. [6] of the document below) ultimately govern the choice of values, and in this respect Carnap remains faithful to Kant.

The overall view sketched by Carnap has some potentially attractive features. It combines a Bayesian decision-theoretic rationality at the cognitive (or more broadly instrumental) level with a kind of minimally Kantian substantive rationality at the level of ultimate values, without claiming (like Kant and some later Kantians) to be able to determine a single, unique highest principle of morality. There is a striking parallel between this idea and the “relativized a priori,” as Michael Friedman has called it, of which different versions are suggested in Poincaré, Schlick, early Reichenbach, Cassirer, and Carnap. Just as (Kantian) unique synthetic a priori knowledge is relativized by these figures to different historical epochs or human purposes, so the (Kantian) unique categorical imperative is relativized by Carnap, in the fragment published here, to the many different fundamental values that prevail in different contexts and cultures. Not only does this conception leave room for value pluralism, then, but it clearly subordinates instrumental rationality to ultimate values in a way that has eluded some well-known attempts to conjoin these different components or levels of rationality.

Carnap’s strongest argument against deriving “perfect” rationality (at least) from successful outcomes comes in his final paragraph (though the connection is not made explicit):

“More rational,” whether applied to different periods or to two possible behaviors of the same person in the same period, cannot very well be exactly defined. Roughly speaking, a behavior is more rational than another when it comes closer to perfectly rational behavior. But since deviations from perfectly rational behavior are possible in completely different ways, e.g. in the ways mentioned above. . . and within each of these once again in different ways, it is hardly possible to decide without an arbitrary convention under what conditions a deviation in one way should be considered equal to a deviation in another way. (p. [10])

This impossibility of comparing, let alone measuring, different deviations from “perfect rationality” is in fact an immediate consequence of the sharp distinction between the criteria for determining instrumental (or partial) rationality from those governing substantive (comprehensive) rationality. If values are chosen by standards that are merely constrained (and not determined) by instrumental considerations, then distance from overall (“perfect”) rationality would be arbitrary even if (as Carnap did not believe) instrumental rationality were only a matter of learning from experience or of past success.

It is both surprising and admirable that Carnap was so bluntly honest with himself about the consequences of his conception of rationality. For of course he was notoriously an advocate of quantitative concepts; he thought that psychology, for instance, would have to become more quantitative to be more scientific. And we find him admitting, here, that a quantitative measure of moral value functions is not feasible. It is probably not an accident that this fragment ends where it does, or that it was not ultimately picked up again and worked out. For while Carnap was honest enough to put down the words just quoted, the conclusion expressed in them must have been unwelcome to him.

A.W. Carus, Introductory Remarks to “Value Concepts” by Rudolf Carnap

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

[D. Criticism of historical meaning - cont'd]

2. Philosophical reading shows that conscious activity is

a. Instinctive (

Beyond good and evil;

see the analysis of Kant's text on synthetic a priori judgments;

Le Gai Savoir on translation).

b. Interpretative: In Nietzsche - man only finds himself in things.

i. What he finds there is science; what he introduces is art.

There is a logic, [which] is an original interpretation.

Encrypted writing.

Postulates of logic: identity, analogy.

Find hidden postulates.

Logic is an abbreviation serving a certain form of will to power.

ii. Metaphysics is an interpretation. The sign must be read genealogically: show how a concept was produced (Sprachwissenschaft, linguistics?).

Interpretation: which allows reading points to be identified.

Genealogy: how an original interpretation develops historically.

Originality: seeing what has never been seen (Le Gai Savoir).

Liebe [Love]: (The Gay Knowledge).

[The manuscript ends here. The rest of this passage has not been found.]

– Michel Foucault, Beginning, Origin, History, (Course given at the experimental university of Vincennes, 1969-1970: Annex 2), from Nietzsche: Cours, conférences et travaux, edited by Bernard E. Harcourt

1 note

·

View note

Text

What Is Synthetic A Priori? Groundbreaking Concept Explained | PhilosophyStudent.org #shorts

Explore Immanuel Kant’s concept of Synthetic A Priori, a type of judgment that’s necessary and independent of experience. Please Visit our Website to get more information: https://ift.tt/X0lpdJs #synthetica priori #kant #philosophy #kantianphilosophy #philosophyeducation #shorts from Philosophy Student https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ckupEpPALtw

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Hegel on Herodotus

I reproduce here an imporant article of Will Desmond about the views of the major German Philosopher G. W. F. Hegel on Herodotus, Hegel’s appropriation of Herodotus and the integration of the latter into the Hegelian philosophy of history, but also about the limits of this appropriation and integration.

“Intellectual History Review Volume 32, 2022 - Issue 3: Ancient and Modern Knowledges / Towards a History of the Questionnaire

Herodotus, Hegel, and knowledge

Will Desmond

Pages 453-471 | Published online: 24 Aug 2022

ABSTRACT

This article locates Hegel’s understanding of the nature of knowledge in various contexts (Hegel’s logical system, Kantian idealism, the Enlightenment ideal of encyclopaedia) and applies it specifically to his systematic classification of histories. Here Hegel labels Herodotus an “original” historian, and hence incapable of the broader vision and self-reflexive method of a “philosophical” historian like Hegel himself. This theoretical classification is not quite in accord with Hegel’s actual appropriation of material from Herodotus’s narrative for his own purposes. These appropriations point in complex ways to dimensions of the “Father of History” which are proto-Hegelian, as well as to other dimensions which are not.

1. Introduction

Concerning the topic of knowledge, questions abound. What can be known? What are the limits of knowledge? Can human knowledge be compared with animal knowledge? With divine knowledge? What is worth knowing? Is knowledge a good? The good? Or an awakening to the futility and tragedy of existence? If knowledge has many objects, modes, and divisions, can these be organized into an articulated whole? Or does the plurality covered by the word “knowledge” resist systematization, because there are knowledges that are qualitatively different, and not species of a single genus? Questions like these are old, perhaps perennial. But they become especially prominent in modern European thinking. Descartes is traditionally taken as a symbol of the beginnings of a “modern,” keenly self-conscious, and methodically self-critical quest for certain knowledge. Among the many who laboured in the wake of Descartes is Hegel, in some ways so Cartesian, with his confidence in the power of a priori ideas, and a narrative of Geist that elides the sense of difference between human and divine minds, both illuminated by the natural light of reason. On the other hand, Hegel is one of the most empirical and historically minded of thinkers. This fact gives one an entrée to a rather unusual juxtaposition: Hegel and one of the many whom he takes as a significant predecessor, Herodotus, “Father of History.” With a view to evaluating Hegel’s attempt to make something modern of Herodotus and his Histories, this article will comprise three parts: (1) a snapshot of Hegel’s systematic, post-Kantian approach to the nature and organization of knowledge; (2) a synopsis of both his theoretical understanding and practical use of Herodotus; and (3) an exploration of ways in which Herodotus’s work can be regarded as proto-Hegelian, or not.

2. Hegel’s ideal of a philosophical encyclopaedia of the Wissenschaften“

The true is the whole” (Das Wahre ist das Ganze) is the pithy phrase Hegel often uses to summarize his holistic and systematic approach to knowledge. Though his own work in revising lectures and previous publications was cut off by a premature death, his long ambition was clearly to coordinate all disciplines into a single, consistent, and tolerably complete whole; a system that would organize all human knowledge into a single, presuppositionless whole. His Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences (1817, revised 1827, 1830) is the closest approximation to this ideal whole, but its root understanding of knowledge draws most significantly on Kant’s critical philosophy. Kant’s project of transcendental critique would, of course, find a synthetic a priori element in all experience: physical, moral, aesthetic, even political and historical. Kant’s own language tends to associate knowledge claims with those disciplines central to the First Critique – namely to arithmetic, Euclidean geometry, and Newtonian mechanics – which together articulate the empirical laws of nature and reality, i.e. phenomenal reality.Footnote1 Kant argues that the stuff of sense experience comes shaped by the transcendental forms of time, space, and the categories of the understanding. Namely, phenomena are the synthesis of two elements: the sensual and a posteriori, and the categorical or synthetic a priori, or, in Aristotelian terms, the matter of sensuous intuition comes shaped by the a priori forms of the experiencing subject.Footnote2

Hegel, for his part, stresses more the logical unity of these two analytic elements of intuition and the synthetic a priori. The sensual Anschauung provides the particular filling of experience, while the subjective categories provide the universal framework for empirical intuitions. Particular and universal become abstract aspects of the concrete reality; the phenomenal individual. This triad of universal, particular, and individual becomes for Hegel the key to all reality and knowledge, including knowledge of the past. For example, in all disciplines, a scientifically organized study should begin with a universal concept (Begriff) which broadly delimits the subject matter. From this, it should proceed to relevant particulars (Besondere), relating them to each other, and to the universal concept that unites them. The result is a holistic understanding of phenomena as concrete individuals (Einzelne) in whose particularity the universal concept is uniquely manifested. Again, each entity or phenomenon exhibits the same fundamental “life-cycle”: a universal notion or essence evolves or unfolds its inner determinations, thus particularizing itself into a plurality of parts, each of which manifests the entity’s whole essence, and which together constitute the entity as an individual. Hegel deploys this triad very widely, and it goes to the heart of his idealism, which proclaims that thinking and being share the same inner structure: in Hegel’s language, all that exists exists inasmuch as it is the Idea, and his Berlin lectures in particular attempt to articulate this ontological logic as it works itself out through such disparate phenomena as the will and human communities (family, state), art works (of all periods and genres), religions of the world, philosophies of the past, even the totality of human history itself.Footnote3 Each of these objects of thought is knowable inasmuch as it reflects the inner logical structure of the thinking subject.

Hegel’s logical triad of universal–particular–individual appears in somewhat disguised form in the division of his Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences. This is an encyclopaedia of human knowledge, though in the older, pre-Diderot style: not arranged alphabetically and thus quasi-democratically, but hierarchically, from controlling ideas down to subordinate details. The three main sections are Logic, Nature, and Spirit; a division that, for Hegel, is both rationally necessary and historically mediated, and which he might agree is both “ancient” and “modern,” as well as neither.Footnote4 Less paradoxically, Hegel envisions his three parts as a holistic trinity of equals: each part implies and is implied by all the others, such that there is no single foundational principle. As Inwood writes: “The universe [For Hegel] involves the logical idea (U), nature (P) and spirit (I): in his system, Hegel presents them in the order U-P-I, but any order would be equally appropriate, since each term mediates the other two.”Footnote5

These remarks provide some background for Hegel’s thinking about history and historical knowledge. Firstly, the triad Logic–Nature–Spirit is an articulated whole: each part is different from, yet related to, every other. Each shows internal development or evolution by which it “unfolds” from its universal, but only spirit has temporal development. Namely, Spirit is historical, indeed the realm of history is Spirit, for Spirit is essentially marked by the dynamic dialectic of the logical Concept as it expresses itself in time, and each moment of Spirit – from the subjective Spirit of psychology and individual experience, to the objective Spirit of the state, to the absolute Spirit of historical arts, religions, and philosophies – is bound to time, and sees development from the inchoate to the complex. Perhaps the most celebrated, and obvious, aspect of Hegel’s attempt at an encyclopaedic world history posits the same basic intelligibility percolating through each of the four world historical civilizations. The Oriental, Greek, Roman, and Germanic worlds are governed by their own unique and irreducible “spirit” or cultural paradigm: a universal principle which particularizes itself into its many individual customs, institutions, beliefs, and cultural artefacts; thus each national spirit develops, blossoms, or actualizes itself, and then declines and bequeaths the ghost, as it were, to the next world historical people.

In contrast to all this is Hegelian Nature, which has no history; a proposition that simply reflects scientific orthodoxy before Darwin. But unlike a later orthodoxy that would separate the natural sciences and humanities, Naturwissenschaften and Geisteswissenschaften, Hegel’s systematic also posits an inner continuity between Nature and Spirit: Nature is known also according to the U–P–I triad, and can be related to Spirit as its “ground”: at once the backdrop for, material of, and a moment in Spirit, which actively sublates Nature into its own all-embracing actuality. This becomes more concrete in the Lectures on the Philosophy of World History, which begin, rather conventionally, with a chapter on “The Geographical Basis of History.” Such prefaces are often written in a quasi-materialistic vein: “geography is destiny” is a modern proverb and guiding assumption here, to which one might offer, as an ancient parallel, the evocative conclusion of Herodutus’s Histories, “from soft lands, soft peoples.”Footnote6 For Hegel, by contrast, geography is the basis or “ground” of history, not because it determines it, but because it expresses in a merely inchoate way what would become explicit and self-conscious in the higher productions of culture and Geist. Namely, “ideas” implicit in a geographical region are made explicit in national character and development; geography is thus subordinated to the higher discipline of historiography. The point is illustrated by Hegel’s remarks on Ionia: the Ionian climate, Hegel notes, is not the cause of Homer’s epics, though in his Neoclassical/Romantic vision, the beauty of Ionia and the Aegean, with their free interplay of mountains and sea – in countless islands and bays, that are both separate from each other, yet bound together by the “middle sea” (Mittelmeer) – is only the backdrop and material that would be expressed more perfectly in the manifold beauties of Greek culture.Footnote7

Hegel’s theory of the nature of knowledge is complex. It might, however, be characterized as a kind of logical historicism, at once attuned to the timeless, universal patterns behind change and the uniquely particular events of history: the logician in him attends to the recurrent pattern, the historicist to irreducible particulars. Hegel himself acknowledges (inconsistently, in my view) that the logical Begriff cannot utterly inform temporal particulars: “the impotence of nature” renders it resistant to fully reasoned knowledge, while history is marred by contingencies in its fine grain, if not in the broad outlines.

3. Hegel on Herodotus: theoretical classification and practical appropriation

Where does Herodotus fit in this logico-historical system? Hegel accepts Herodotus’s familiar title as “Father of History,” and more specifically he names him as the first example of what he classifies as “original history.”Footnote8 The first in Hegel’s three-fold categorization of types of histories, original history is that in which writers were imbued with the “spirit” of the events they record: subjective knower and known object, historian and historical events (res gestae) are not radically distinguished, but both informed by the same cultural Geist in which they move and have their being. This first and most basic form of history is followed logically and chronologically by two higher types: reflective and philosophical history. Reflective historians are, in all their subspecies, more removed from their objects, either because they are universal historians tackling a huge range of time, pragmatic historians abstracting from or imposing useful lessons on their material, or critical historians who bring their own stringent criteria of plausibility and relevance to their period. The third and final, philosophical type of history also brings a priori elements to bear to sift, judge, and understand the stuff of the past, with the difference that these are synthetic a priori, the necessary rational structure of all minds and all thinking.

Hegel’s classification of histories rests on his sense of the differing relations between knower and known: in original history, the knowing historian is immediately at home with his object and times; in all three subspecies of reflective history (universal, pragmatic, and critical), the historian’s knowledge is mediated through sources (e.g. others’ original histories) somewhat alien to his sensibilities; while philosophical history synthesizes these “opposites,” mediating given data with the true a priori categories that are transcendentally adequate to and illuminative of their objects. Overall, this classification can be understood as a veiled history of histories: historiography progresses, approximately speaking, from Oriental annals and king lists through to the critical and philosophical histories that appear in the wake of Kant’s “critical” philosophy and are one product of the modern “Germanic” spirit, with its defining self-awareness and drive to systematic comprehensiveness. Again, while, for Hegel, the Persians were the “first historical people,” historiography proper begins with Herodotus, and its subsequent types parallel the trajectory of Hegelian world history: in his classification, original history is most exemplified by Greek writers, universal history by Romans, while pragmatic history is explicitly associated with the French, critical and philosophical history with contemporary Germany.Footnote9 Just as, for Hegel, world history culminates in the “Germanic world” of medieval and modern northern Europe, and most of all in contemporary modern Germany, so, as a kind of corollary to this, the practice of history reaches its historical and “logical” fulfilment in the philosophical history of the Hegelian present.

Hegel clearly privileges Germanic modernity over the Oriental, Greek, and Roman pasts. Yet this does not at all devalue past forms of historical knowledge. Rather, his typical concern for the precise dialectic of sameness and otherness is evident also in his categorization of types of history. Namely, his is an ordered and progressive typology. Each form of history is obviously different: Herodotus’s original history is not the same as Hegel’s philosophical one. Yet at a deeper level, the later, more mediated forms incorporate the earlier and less complex: universal histories collate many separate original histories into large or comprehensive wholes; pragmatic and reflective histories take the others as materials for their higher moralizing, or “higher criticism”; philosophical history aims to synthesize the essentials of all the others, creating a comprehensive world history, and even subjecting the reasoning of the so-called “higher criticism” to a yet-higher philosophical critique.Footnote10 To the contemplation of the past, Hegel writes, the philosopher brings nothing but the “simple conception of reason”Footnote11: this true logical canon would enable the Hegelian historian to elicit the inner rational form of materials provided by the “lower” types of history. The result (Hegel claims) is not only the most comprehensive and true history, which reworks the materials given by original and reflective histories into the broadest, most intellectually secure framework. Even more, philosophical history would demonstrate the deepest, trans-temporal rationality of human development. History becomes veiled theodicy, and, “to him who looks upon the world rationally, the world in its turn presents a rational aspect.”Footnote12 In another way, the modern philosophical historian subsumes all past histories into a comprehensive vision that recognizes the timeless core of all human development. For this vision, there is really no “ancient” or “modern,” because all temporal events become necessary moments in the self-unfolding of the eternal Idea.Footnote13

So much for a summary of Hegel’s typology of histories as part of his larger epistemology of the Absolute Idea. From this height, let us descend to more humble details: the main passage in which Hegel introduces his ideas on Herodotus and “original history.”

To this category belong Herodotus, Thucydides, and other historians of the same order, whose descriptions are for the most part limited to deeds, events, and states of society, which they had before their eyes, and whose spirit they shared. They simply transferred what was passing in the world around them, to the realm of representative intellect. An external phenomenon is thus translated into an internal conception. In the same way the poet operates upon the material supplied him by his emotions; projecting it into an image for the conceptive faculty. These original historians did, it is true, find statements and narratives of other men ready to hand. One person cannot be an eye or ear witness of everything. But they make use of such aids only as the poet does of that heritage of an already-formed language, to which he owes so much; merely as an ingredient. Historiographers bind together the fleeting elements of story, and treasure them up for immortality in the Temple of Mnemosyne. Legends, Ballad-stories, Traditions, must be excluded from such original history. These are but dim and hazy forms of historical apprehension, and therefore belong to nations whose intelligence is but half awakened. Here, on the contrary, we have to do with people fully conscious of what they were and what they were about … Such original historians, then, change the events, the deeds, and the states of society with which they are conversant, into an object for the conceptive faculty. The narratives they leave us cannot, therefore, be very comprehensive in their range. Herodotus, Thucydides, Guicciardini, may be taken as fair samples of the class in this respect. What is present and living in their environment is their proper material. The influences that have formed the writer are identical with those which have moulded the events that constitute the matter of his story. The author's spirit, and that of the actions he narrates, is one and the same. He describes scenes in which he himself has been an actor, or at any rate an interested spectator … Reflections are none of his business, for he lives in the spirit of his subject; he has not attained an elevation above it.Footnote14

Though the passage is somewhat jumbled, one can extract several salient points. First and foremost, Hegel is concerned, here at the start of his quasi-logical history of histories, with locating the transition from immediate experience to the mediated artefacts of written memory: namely, the transition from lived experience, with its “fleeting” memories, to the first continuous, prose histories. Here the sources of historical knowledge are necessarily limited to what is immediately to hand. Personal experience and autopsy of “what was passing in the world around them” is obviously one such source, but, because “one person cannot be an eye or ear witness of everything,” seemingly more important are the “statements and narratives of other men,” which expand the horizon of the historian’s experience, vicariously; though even then that horizon cannot be “very comprehensive” in its range. Strangely enough, these narratives seem not to include “legends, ballad-stories, [and mythic?] traditions”: Hegel’s statement may well reflect his low opinion of Niebuhr and his allegedly “critical” sifting of early Roman legends, but it certainly glosses over the folkloristic element in Herodotus, and his frequent use of poets like Homer and Archilochus. More insightful is Hegel’s implication that an original historian such as Herodotus is necessarily limited to oral materials, because, at the very beginning of historiography, written records do not exist. It is original history itself that helps to affect the transition to a written culture, and, though Hegel does not pursue the issue in any detail, his analysis could profitably be extended to Herodotus: Herodotus’s historiē is indeed ostensibly oriented almost exclusively to his travels, to what he saw (opsis) and heard (akoē), to his observations and interviews with logioi andres, and not on the few inscriptions or texts he mentions, let alone on Rankean archives.

Intriguing also for Herodotean studies is the analogy that Hegel draws between original historians and poets, both of whom translate raw experience into an object of contemplation. Elsewhere, Hegel describes his understanding of the process by which the mythopoetic imagination transformed the immediacies of sensed nature into the personalized deities of the pantheon: the pond becomes the form of a Naiad, the babbling stream becomes the Muses’ Hippocrene, the sea storm Poseidon’s wrath. Hegel’s discussions of this spiritualizing activity of “phantasy,” of “prophecy” (manteia), or poetry occur within larger discussions of Greek religion and history: poetry in this sense is for him clearly an activity distinctive of Greek culture.Footnote15 If so, a Greek (and Herodotean) invention of history would be its prose counterpart. But while the poet transforms natural immediacies into divine archetypes of the spiritual imagination, hovering ambiguously between sensation and rational understanding, the original historian, by contrast, changes current experience “into an object for the conceptive faculty.” Namely, an original prose history can be thought and reasoned about in general terms (i.e. concepts), and so furthers the emergence of a more philosophical or theoretical culture. But, if Hegel does not fully explain the inner workings of the mythopoetic imagination, neither does he here shed much light on the transformative process of historical composition. His original historians seem to do their work semi-automatically. Personal experience and borrowed statements are there as “ingredients”; “fleeting elements” for the historian simply to “bind together” into an “object” for conceptual thinking. This binding and shaping of materials seems to be almost instinctive with Hegel’s original historian, with little room for selection and judgment. Indeed, “reflections are none of his business,” for it is only with “reflective” history that the historian culls his material in light of some abstract end or criterion. A casual remark on Herodotus’s “naïve account” of the “Constitutional Debate” seems to fill out Hegel’s image of him as a rather unthinking recorder of what he saw and heard.Footnote16

While this follows on from Hegel’s differentiation of “original” and “reflective” histories, one might query whether it is fully consonant with his own post-Kantian epistemology, by which known phenomena are pervaded with, even constituted by, the mind’s a priori categories. So, more specifically, of historiography, Hegel writes that “a simply receptive attitude” is impossible, for every historian “brings his categories with him, and sees the phenomena … exclusively through these media.”Footnote17 Again, Hegel does not develop the thought in relation to Herodotus, but his statement does prefigure the scholarship that has exploded perceptions of Herodotus as a naïve, simple, and uncomplicated raconteur, who (in Hegel’s terms) simply bound together whatever materials he saw and heard, re-telling the “statements and narratives” that others told him, without much critical reflection: on the contrary, reflection was very much his “business,” and gnōmē is the critical element in Herodotus’s “methodology.” So, where Hegel speaks in general terms of the “categories” that must colour ever historian’s vision, specialized studies by Hartog, Thomas, Boedeker, Raaflaub, and others have pointed to the “thought patterns” which Herodotus imposes on or discovers in his material:Footnote18 for instance, the analogies that he (and some Presocratics) makes between the seen and unseen; the polarities of hot and cold, wet and dry, that fascinate him as much as they do contemporary geographers, doctors, and cosmologists; the mechanism of “mixing” and “separation” that he seems to apply metaphorically to the Aegean region, where east and west, north and south meet and create new cultural compounds. In addition to such contemporary scientific “thought patterns” or “categories,” this Herodotus draws on the discourses of heroic epic, contemporary tragedy, Sophistic rhetoric and epideixis, even philosophical forays into epistemology. In all these ways, Herodotus’s mind is deeply formed by his intellectual milieu.

Hegel would grant the point, though in quite different terms. In Hegel’s own terms, the spirit of “original” historians reflects and is the spirit of their times, and its categories of explanation are their own: Herodotus was a man of his times, times when the world Spirit had alighted on the Greek world and infused it with its own energy. Of course, Hegel’s sense of this contemporary “spirit” is very different from that of a Thomas or Raaflaub. In the wake of Winckelmann’s philhellenism, Hegel construes the Greek world to have been naïvely at home with itself: living around the beautiful Aegean, with its lovely mountains and seas, Hegel’s Greeks are not alienated from nature, either because of work (done by slaves) or by a Judaeo-Christian sense of fallenness; the Olympian gods are the mirror image of human beings, perfected in beauty and happiness; and in pre-Sophistic days, these Greeks did not experience the social alienation that comes with critical thinking, and that emerged first with the Sophists and Socrates. Chronologically, and as an “original” historian, Hegel’s Herodotus would seem to belong to this prelapsarian, pre-Socratic Greece. But since (for Hegel) nobody, not even superlative minds like Plato and Aristotle, can “overleap” their times,Footnote19 and since the Greek Spirit does not feature the critical distance necessary for reflective and philosophical history, Hegel would agree that Herodotus was, in his own style, a “modern” man of the mid-fifth century B.C., but still a Greek, and therefore not at all a spiritual contemporary of a Gibbon or Ranke.

Such an inference would have to include Hegel’s Thucydides also. In the passage quoted, one might be surprised to find Herodotus and Thucydides juxtaposed as “historians of the same order.” Hegel does not contrast them as naïve story-teller and rigorous scientist; as historical jongleur who tells “myths” for hearers’ momentary pleasure, and serious political analyst suggesting pragmatic lessons about human nature for future readers; as an Archaic traditionalist, keenly aware of divine agency in history, and a more Sophistic progressive who ignores it. The passage also does not contrast Herodotus qua traveller and “interested spectator” with Thucydides, the exiled naval officer and one time “actor” in the war he records; it does not use such a contrast to make Thucydides a cooler, more objective historian than Herodotus. It does not even contrast their vastly different spatial and chronological ranges: world-wide in Herodotus’s case, narrowly focussed in Thucydides’s. Thus, Hegel glosses over the salient differences between the two that have much preoccupied modern scholars, including Hegel’s Heidelberg colleague, Creuzer.Footnote20 These differences can sometimes be reduced to a ranking of the two in order of their value and/or greater “modernity.” One tendency here is to rank Thucydides above Herodotus because he seems more fully empirical, sceptical, and non-religions, therefore more “scientific” and hence more “modern.”Footnote21 In Hegel’s world historical scheme, by contrast, “modernity” is Lutheran and scientific, sceptical and idealist, with an internal complexity beyond anything in the ancient Greek world. Hence, for Hegel, the differences between Herodotus and Thucydides melt away before their shared Greekness, and he simply classifies them as original historians, as if they were both simply transcribing contemporary events into written memory.

Hegel’s simple labelling of Herodotus as “original” cuts across other, more obvious dimensions to Herodotus’s work. Most salient is the fact that Herodotus is not quite a contemporary historian: the Greek events he narrates are 50, 75 years in the past; his Lydian, Persian, and Egyptian logoi deal with even older material; the historiē that he pursues takes him ostensibly from Sicily to Babylon, from Egyptian Elephantine to the Scythian Black Sea and beyond; the cultures and chronological vistas of those exotic peoples slip through whatever explanatory “categories” or Greek “thought-patterns” that Herodotus bears upon them. It seems only very partially true, then, that Herodotus’s spirit is “one and the same” with that of the matter he narrates: true enough of the later books’ events that are set more firmly in Greece, with Greek protagonists, but hardly true of their Persian opponents, let alone of the Egyptian or Indian wonders that crowd the earlier logoi.

Given his vast range and his mental distance from much of his material, Herodotus may in some ways more resemble Hegel’s universal historian.Footnote22 Indeed, Hegel himself treats him practically as such, when he turns from theoretical labels to actually reading Herodotus and incorporating him into his own philosophical history. Such a careful reading of original historians he recommends emphatically: a comprehensive modern education involves learning the Greek world from the inside, and Herodotus, Thucydides, and Xenophon are here indispensable.Footnote23 And yet, when he cities Herodotus, it is not just as a source of knowledge for the Greek world but also for aspects of the Oriental world and even Africa. In his approximate 48 citations of Herodotus in the Philosophy of History, Hegel draws information about Egyptian architecture, art, and religion, the Egyptian caste systems, Phoenician merchants, Babylon and the cities of Assyria, the Persian empire and Zoroastrianism, and the politics of Oriental despotism.Footnote24 Some of Herodotus’s statements become quite important for Hegel. The Herodotean claim that the Greeks initially received many of their gods from Egypt bolsters Hegel’s argument that Egypt was the point of transition between the Oriental and Greek Worlds.Footnote25 Or again, Herodotus’s account of the Constitutional Debate, and more diffusely of Egyptian pharaohs and monarchs like Croesus, Cyrus, and Xerxes must inform Hegel’s generalization that the constitution natural to the Oriental world was tyranny. Likewise, one could surmise that Herodotus’s narrative of the freedom-loving but fractious poleis that barely allied against Xerxes informed Hegel’s generalization that democracy was the fundamental constitution of the Greek world. If so, then there is significant Herodotean background to the celebrated passage in which Hegel sums up his vision of world history as the progressive triumph of freedom:

The East knew and to the present day knows only that One is Free; the Greek and Roman world, that some are free; the German World knows that All are free. The first political form therefore which we observe in History is Despotism, the second Democracy and Aristocracy, the third Monarchy.Footnote26

Such generalizations are very much informed also by the way that Hegel incorporates Herodotus’s “original” history into his own vast philosophical world history. In one passage, Hegel interprets the Iliad and later epics in terms of an almost perennial struggle between Asia and Europe:

[I]n the Iliad … the Greeks take the field against the Asiatics and thereby fight the first epic battles in the tremendous opposition that led to the wars which constitute in Greek history a turning-point in world-history. In a similar way, the Cid fights against the Moors; in Tasso and Ariosto the Christians fight against the Saracens, in Camoens the Portuguese against the Indians … We are made completely at peace by the world-historically justified victory of the higher principle over the lower which succumbs to a bravery that leaves nothing over for the defeated. In this sense, the epics of the past describe the triumph of the West over the East, of European moderation, and the individual beauty of a reason that sets limits to itself, over Asiatic brilliance and over the magnificence of a patriarchal unity.Footnote27

The passage does not name Herodotus and Xerxes’s brilliant entourage. But, elsewhere, Herodotus’s Proem lies definitely in Hegel’s mind as he reflects on Homeric culture and the Trojan War:

While this state of things prevailed, and social relations were such as have been described, that striking and great event took place—the union of the whole of Greece in a national undertaking, viz., the Trojan War; with which began that more extensive connection with Asia which had very important results for the Greeks. (The expedition of Jason to Colchis—also mentioned by the poets—and which bears an earlier date, was, as compared with the war of Troy, a very limited and isolated undertaking.Footnote28

It is not “the poets,” of course, who suggest understanding Jason’s Argo, the Argive fleet, and Xerxes’s armada as products of the same geo-political dynamic. It is Herodotus who tantalizingly places mythic raids and historical wars on the same historical continuum. This suggestion of the Proem Hegel takes up and generalizes even further: the “national expedition” led by Achilles becomes the founding act of the Greek world, to be matched by its closing act, Alexander, as a second Achilles, again uniting Greece in a war of conquest against the Oriental World. Even more generally: Greece’s wars against the Orient define the Greek character just as much as the Crusades defined high medieval Christendom.Footnote29 In such passages, one sees the key dynamic of Hegel’s world-history – the mantle of Spirit passing from one civilization to another, and here specifically from the Orient to Greece – drawing on Herodotus as source and authority.

In this regard, perhaps the most revealing pages are those on “The Wars with the Persians,” where Hegel simply recommends reading the “brilliant description” of them by Herodotus.Footnote30 Content to give the briefest synopsis of events, Hegel moves on to what he regards as the larger (one might say “philosophical”) implications of the Greeks’ “world-historical victories”:

In the case before us, the interest of the World’s History hung trembling in the balance. Oriental despotism—a world united under one lord and sovereign—on the one side, and separate states—insignificant in extent and resources, but animated by free individuality—on the other side, stood front to front in array of battle. Never in History has the superiority of spiritual power over material bulk—and that of no contemptible amount—been made so gloriously manifest. This war, and the subsequent development of the states which took the lead in it, is the most brilliant period of Greece. Everything which the Greek principle involved, then reached its perfect bloom and came into the light of day.Footnote31

Thus, Marathon, Salamis, and Plataea not only perfectly exemplify the Greek Spirit. Not only do they signify the victory of Greek freedom over Oriental tyranny. Even deeper is the metaphysical lesson that Herodotus’s account harbours. The Greek victories over such overwhelming odds manifest the truth of absolute idealism itself, for there one can clearly witness the “superiority of spiritual power over material bulk.” More abstractly, the necessary reality of the universal Concept ultimately prevails, through particular historical events (like Herodotus’s wars), over the inertia of the material and irrational.

One need not chase down all the more minor citations to draw the main conclusion: not only does Hegel take from Herodotus a far broader range of historical information than he should from an “original” historian, key Herodotean passages also help him to bolster his larger philosophico-historical generalizations about Greece, the Orient, freedom, reason, and the nature of reality itself. In practically treating Herodotus as a universal historian, Hegel tacitly follows Kant’s lead. Kant sought a universal history guided by the “Idea” of freedom; the early stages of this history would have to be mediated through Greek historiography, which offered the only real knowledge about “older or contemporary” peoples.Footnote32 With more historical acumen (though not full internal consistency), Hegel turns to Herodotus as a major, de facto source for knowledge about Egypt, Persia, and so forth. Passages like those quoted above see Herodotus being incorporated into Hegel’s philosophical history, and thus upgraded to a part of a quintessentially “modern” composition. Indeed, Herodotus becomes an essential moment in that most comprehensive of Enlightenment projects: a universal and reflectively self-critical history of the progressive self-liberation of the human race.

4. Herodotus the proto-Hegelian?

Could Hegel press on to interpret Herodotus not merely as an important source but also as a philosophical historian in his own right? Hegel was not, of course, the first to use the term “philosophical” history. The epithet was used of Hume, Robertson, Gibbon, and other Enlightenment historians.Footnote33 Gibbon, in turn, admired Tacitus as the “philosophic historian” who could discern the essential fact or motive beneath a chaotic mass of happenings.Footnote34 Such uses of the term are not unrelated to Hegel’s. Though keenly aware of the changing connotations of the word,Footnote35 he firmly associates “philosophy” itself with systematic, organized, “encyclopaedic” Wissenschaft. But fully systematic knowledge like this he does not associate with the Greek world at all: for Hegel, not even Aristotle is properly systematic, but rather only a “perfect empiricist” who could “recognize the truth in the particular, or only a succession of particular truths.”Footnote36 Here is another perspective on why Hegel does not classify Herodotus as “philosophical” (and hence fully modern) historian.