#Joseph while knowing that his son was meant for greater things still taught him his craft

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

carpenter's boy

#there’s just something about remembering that Jesus was a boy once#just a kid excited for the life ahead of him#so pure and innocent and full of life#Joseph while knowing that his son was meant for greater things still taught him his craft#idk haven’t really read the Bible in a long while#haven’t really thought about Jesus other than someone beyond what the world thinks of him#but remembering that for a brief moment of time he was just a kid happy to be spending time with his father#that gets to me a bit more than I ever thought it would

24K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Best Quotes on Fatherhood

Fathers tend to be taken for granted.

We invariably make more of a fuss over Mom on Mother’s Day than Dad on Father’s Day, for one.

Dads are like a steady but less sentimentalized institution — the sun in our familial sky that warms and gives life but isn’t much thought about unless he goes missing.

Yet this belies the enormous impact fathers truly have on their children; while a dad’s nurturing may often take the form of playful roughhousing and silly jokes, his influence is quite serious and significant: the presence of a loving father greatly increases a child’s chances of success, confidence and resilience, physical and mental well-being, and yes, quite naturally, their sense of humor.

One of the manifestations of the way we take fathers for granted is that there exist many more quotes about Mom than dear old Dad (and even fewer about fathers and daughters). To make more accessible those great pearls of wisdom that do exist, we searched high and low for the very best, and created this ultimate treasury of quotes about fatherhood. These short quotations provide great prompts for reflection; typically, we’re so busy plowing ahead that we don’t pause to look up and get a “birds-eye” perspective on things — taking the time to ponder what our own dads meant to us, and the way we’re shaping, and should be savoring, our kids right now.

Quotes About Fatherhood

“You don’t raise heroes, you raise sons. And if you treat them like sons, they’ll turn out to be heroes, even if it’s just in your own eyes.” –Walter M. Schirra, Sr.

“Some dads liken the impending birth of a child to the beginning of a great journey.” –Marcus Jacob Goldman

“One father is more than a hundred schoolmasters.” –George Herbert

“Sherman made the terrible discovery that men make about their fathers sooner or later . . . that the man before him was not an aging father but a boy, a boy much like himself, a boy who grew up and had a child of his own and, as best he could, out of a sense of duty and, perhaps love, adopted a role called Being a Father so that his child would have something mythical and infinitely important: a Protector, who would keep a lid on all the chaotic and catastrophic possibilities of life.” –Tom Wolfe, The Bonfire of the Vanities

“The best way of training the young is to train yourself at the same time; not to admonish them, but to be seen never doing that of which you would admonish them.” –Plato

“The nature of impending fatherhood is that you are doing something that you’re unqualified to do, and then you become qualified while doing it.” –John Green

“One of the greatest things a father can do for his children is to love their mother.” –Howard W. Hunter

“To a father growing old nothing is dearer than a daughter.” –Euripides

“If there is any immortality to be had among us human beings, it is certainly only in the love that we leave behind. Fathers like mine don’t ever die.” –Leo Buscaglia

“That is the thankless position of the father in the family—the provider for all, and the enemy of all.” –J. August Strindberg

“Every father should remember one day his son will follow his example, not his advice.” –Charles Kettering

“Son, there are times a man has to do things he doesn’t like to, in order to protect his family.” –Ralph Moody

“A boy needs a father to show him how to be in the world. He needs to be given swagger, taught how to read a map so that he can recognize the roads that lead to life and the paths that lead to death, how to know what love requires, and where to find steel in the heart when life makes demands on us that are greater than we think we can endure.” –Ian Morgan Cron

“Parenthood remains the single greatest preserve of the amateur.” –Alvin Toffler

“My father didn’t tell me how to live. He lived and let me watch him do it.” –Clarence Budington Kelland

“When you’re a dad, there’s no one above you. If I don’t do something that has to be done, who is going to do it?” –Jonathan Safran Foer, Here I Am

“‘Why do men like me want sons?’ he wondered. ‘It must be because they hope in their poor beaten souls that these new men, who are their blood, will do the things they were not strong enough nor wise enough nor brave enough to do. It is rather like another chance at life; like a new bag of coins at a table of luck after your fortune is gone.’” –John Steinbeck, Cup of Gold: A Life of Sir Henry Morgan, Buccaneer, with Occasional Reference to History

“If the past cannot teach the present, and the father cannot teach the son, then history need not have bothered to go on, and the world has wasted a great deal of time.” –Russell Hoban

“There are many kinds of success in life worth having. It is exceedingly interesting and attractive to be a successful business man, or railway man, or farmer, or a successful lawyer or doctor; or a writer, or a President, or a ranchman, or the colonel of a fighting regiment, or to kill grizzly bears and lions. But for unflagging interest and enjoyment, a household of children, if things go reasonably well, certainly makes all other forms of success and achievement lose their importance by comparison.” –Theodore Roosevelt

“Father!—To God Himself we cannot give a holier name.” –William Wordsworth

“We think our Fathers Fools, so wise we grow; Our wiser Sons, no doubt, will think us so.” –Alexander Pope

“His values embraced family, reveled in the social mingling of the kitchen, and above all, welcomed the loving disorder of children.” –John Cole

“Children are a poor man’s riches.” –English proverb

“It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men.” –Frederick Douglass

“A girl’s father is the first man in her life, and probably the most influential.” –David Jeremiah

“Fathers, like mothers, are not born. Men grow into fathers and fathering is a very important stage in their development.” –David Gottesman

“Father of fathers, make me one,

A fit example for a son.”

–Douglas Malloch

“I believe that what we become depends on what our fathers teach us at odd moments, when they aren’t trying to teach us. We are formed by little scraps of wisdom.” –Umberto Eco

“My father used to play with my brother and me in the yard. Mother would come out and say, ‘You’re tearing up the grass.’ ‘We’re not raising grass,’ Dad would reply. ‘We’re raising boys.’” –Harmon Killebrew

“Until you have a son of your own . . . you will never know the joy beyond joy, the love beyond feeling that resonates in the heart of a father as he looks upon his son. You will never know the sense of honor that makes a man want to be more than he is and to pass something good and hopeful into the hands of his son. And you will never know the heartbreak of the fathers who are haunted by the personal demons that keep them from being the men they want their sons to be.” –Kent Nerburn

“When my son looks up at me and breaks into his wonderful toothless smile, my eyes fill up and I know that having him is the best thing I will ever do.” –Dan Greenberg

“Being a great father is like shaving. No matter how good you shaved today, you have to do it again tomorrow.” –Reed Markham

“It is easier for a father to have children than for children to have a real father.” –Pope John XXIII

“When I looked at you first I saw not your mother and me, but your two grandfathers . . . and, as my father, whom I loved a great deal, had died the year before, I was moved to see that here, in you, he was alive.” –Peter Carey

“Dads are most ordinary men turned by love into heroes, adventurers, story-tellers, and singers of song.” –Pam Brown

“‘Father’ is the noblest title a man can be given. It is more than a biological role. It signifies a patriarch, a leader, an exemplar, a confidant, a teacher, a hero, a friend.” –Robert L. Backman

“Noble fathers have noble children.” –Euripides

“The father who does not teach his son his duties is equally guilty with the son who neglects them.” –Confucius

“No man can possibly know what life means, what the world means, what anything means, until he has a child and loves it.” –Lafcadio Hearn

“I cannot think of any need in children as strong as the need for a father’s protection.” –Sigmund Freud

“A father is a man who expects his son to be as good a man as he meant to be.” –Frank A. Clark

“His father watched him across the gulf of years and pathos which always divide a father from his son.” –John Marquand

“A family needs a father to anchor it.” –L. Tom Perry

“Words have an awesome impact. The impression made by a father’s voice can set in motion an entire trend of life.” –Gordon MacDonald

“Children need models rather than critics.” –Joseph Joubert

“A father is someone you look up to no matter how tall you grow.” –Unknown

“Certain is it that there is no kind of affection so purely angelic as of a father to a daughter. In love to our wives there is desire; to our sons, ambition; but to our daughters there is something which there are no words to express.” –Joseph Addison

“Mostly you just have to keep plugging and keep loving—and hoping that your child forgives you according to how you loved him, judged him, forgave him, and stood watching over him as he slept, year after year.” –Ben Stein

“Life doesn’t come with an instruction book — that’s why we have fathers.” H. Jackson Browne

“Fathers, you are your daughter’s hero. My father was my hero. I used to wait on the steps of our home for him to arrive each night. He would pick me up and twirl me around and let me put my feet on top of his big shoes, and then he would dance me into the house. I loved the challenge of trying to follow his every footstep. I still do.” –Elaine S. Dalton

“A good father is one of the most unsung, unpraised, unnoticed, and yet one of the most valuable assets in our society.” –Billy Graham

“When you teach your son, you teach your son’s son.” –The Talmud

“My father always said there are four things a child needs: plenty of love, nourishing food, regular sleep, and lots of soap and water. After that, what he needs most is some intelligent neglect.” –Ivy Baker Priest

“Like so much between fathers and sons, playing catch was tender and tense at the same time.” –Donald Hall

“By profession I am a soldier and take great pride in that fact, but I am also prouder, infinitely prouder, to be a father. A soldier destroys in order to build; the father only builds, never destroys.” –General Douglas MacArthur

“The lone father is not a strong father. Fathering is a difficult and perilous journey and is done well with the help of other men.” –John L. Hart

“Children of the new millennium when change is likely to continue and stress will be inevitable, are going to need, more than ever, the mentoring of an available father.” –Ian Grant

“The quality of a father can be seen in the goals, dreams, and aspirations he sets not only for himself, but for his family.” –Reed Markham

“Fathering is not something perfect men do, but something that perfects the man.” –Frank Pittman

“Never fret for an only son. The idea of failure will never occur to him.” –George Bernard Shaw

“My son is seven years old. I am fifty-four. It has taken me a great many years to reach that age. I am more respected in the community, I am stronger, I am more intelligent and I think I am better than he is. I don’t want to be his pal, I want to be a father.” –Clifton Fadiman

“Some day you will know that a father is much happier in his children’s happiness than in his own. I cannot explain it to you: it is a feeling in your body that spreads gladness through you.” –Honore de Balzac, Pere Goriot

“A child enters your home and for the next twenty years makes so much noise you can hardly stand it. The child departs, leaving the house so silent you think you are going mad.” –John Andrew Holmes

“Every parent is at some point the father of the unreturned prodigal, with nothing to do but keep his house open to hope.” –John Ciardi

0 notes

Photo

&& HE IS SON OF BLASPHEMY, WITH ROT BLACK IN HIS VEINS ━━━ upbringing

the name of odin christiansen is a name reeking with fear on one side of the world and admired in another ━ for the norwegian archbishop of oslo had already rumors about a strict and rather phobic discipline upon his administration, maniac in his search for the divine perfection he thought ( knew ) he could incarnate in his role as shepherd for the lost. such a saintly man! such a righteous man with strong power in his hands reined with just observance and nothing making his faith quiver! such a great example for the modern church to take as, such a model to admire with godfearing plight.

and oh, if they were all so wrong.

because that very man who claimed righteousness while reeking filth from hands behind his back had broken all rules, all of them ━when he himself had indulged more than once in the sins he’d preached as malevolent and poisonous for the frail human soul, using excuses of travel and representative duties to embark in the greatest sin he had ever committed.

a family in secret, and a son indoctrinated.

he never got married to sweet magdalene of lutheran branch, and she was perfectly okay with that albeit being herself woman of strict doctrine ━aware of what she was going forwards, but even more aware of a greater design having herself and the son in her womb as focal point of it. so devotedly she’d support the beloved one in his affairs and in the development of his own poison, not even once questioning, not even once rebelling to his bidding. so blind she was!, and she was so okay with that ━foolish even, when accepting to move to an anonymous cul-de-sac in the depths of virginia after their little abomination had been given birth, his mouth filled with promises and her own mouth drinking from each one of them.

everything had to be done his way, no other way was as perfect.

so when little joseph was born ━named like the father of christ, meant to bring the light in the world, she said ; his holiness debating to her with that second name, fenris, the name of the wolf born from wickedness of mischief━, he was born with bishop surname and bishop hand over his head to pull his strings and make sure the little thing would come out perfect, and with mother being sure to hold his head still while getting him drunk with doctrine. ODIN MADE HIMSELF GOD AND HIS SON BECAME MUD TO BREATHE LIFE IN, INCARNATION OF BLASPHEMY. there was no margin of error, all of him had to be scheduled, programmed, imbued.

with two strong faiths he had grown up and secrets wrapped around his body at night and never meant for them to be found out, little joseph, but none of them would compensate the bad health he was given ever since he’d learnt how to walk and talk and hold a bible in his tiny hands. often sickly pale he was, often coughing, often with knee scrapped because of how prone to lose his balance was ━so small indeed, such a perfect prey for those who found solace in being harbingers of injustice himself when it was time, for him, to attend the local religious school; he was taught not to fight and endure, and that’s what he’d do, giving the other cheek if hurt, letting the punch paint his whiteness with blues and purples and yellows and greens, letting cut and blisters appear like stigmata on a martyr.

MARTYR CHILD HE WAS, GODLY CREATION, GODLY DEVOTION.

his mouth was filled with precepts and bible verses, chants them for he knows nothing else, has approached nothing else. a model child with hair always perfect and shirt always tucked inside his short and small golden cross around his neck, picture perfect like the always modest mother ━shivers down his spine when praised as a good boy, when petted on the head at the same spite a dog would have.

he’d sit down if commanded, stand up, turn around ━hold things above his head in posture, but head always down in mute respect when nuns and priests were over at the big hose of the bishop’s wife, always sitting in the smallest chair next to her imperial figure, dumb and numb to the loved praise.

( more, more, more! )

he only wanted to be good, so good for that father coming one week every month in their house, he wanted to be so good he’d receive smile and praise to heal the bruise on his lip and the limp in his step! he didn’t want the punishments or the screeching, the segregation up in attics where the only things inhabiting the dark and cluster of that lieu were moths ━and moths prey on pretty things, it is known━, he didn’t want the solitude and the cold to pierce is skin to the point he’d feel the hurt but no gash was there, he despised the emptiness and the void and the way it made his stomach churh, the psychological massacre.

for the child was human and of course, as human, prone to mistake ━failure, even if a speck of it, was meant with the heavy glance of disappointment and the even heavier silences of shame, turning pale boy in pale ghost to ignore until it was clear that he’d learnt his lesson and would utter of mother and father in begging motions, that he starved enough to kneel and kiss sacred symbols and usher prayers in calming mantras. not a hand was rose onto those cheeks, not even once ━both odin and magdalene knew about how much more powerful the emotional pressure was, how that would make their perfect god-child even more perfect in the fright of god, pretty little soldier to move around in their godly scheme, one mental gash at a time.

UNTIL SHE ARRIVED AND TAINTED HIM, BROUGHT HIM ASTRAY.

#child abuse //#emotional abuse //#grooming //#bullying //#blasphemy //#part 2 will arrive soon and it will talk about jo and mary's friendship and how they grew up together!#but for now forgive any mistake ive been awake for so long and i think it's the moment for me to go sleep#‹ development. ›

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading, Writing & Real Life

Sometimes I get asked who or what influenced me most in my deep-seated (and very early) desire to write.

I’ve named books and writers: Tristram Shandy (don’t miss the book, but don’t miss the movie either), Norse mythology, and Henry Green, Alice Munro, Grace Paley and Hubert Selby Jr., Ralph Ellison, Italo Svevo, Sigrid Undset and Zora Neale Hurston. For the last few years I’ve been working on a series of loosely connected short stories suggested by Dawn Powell’s novel My Home Is Far Away, a book that I can best describe as suggesting the tone of Ingmar Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander transplanted to the world of Winesburg, Ohio. Which could lead me to Hemingway, or Hemingway’s Boat, or – well, I’m sure you get the point.

There were teachers, certainly. Omar Pound (Omar Shakespear Pound, son of Ezra) is the one who stands out the most. He came to Roxbury Latin when I was in the ninth grade and was greeted with almost universal rejection bordering on scorn by my classmates – for his oddity, for his self-determined eccentricities, for his stubborn scruffiness, both personal and intellectual. But for me, and a few others, he provided a wonderful opportunity for self-expression in the two or three extended writing exercises he assigned each week, suggested by a phrase or saying that he provided, of which the only one that comes immediately to mind is, “Only a fool learns from experience.” True? Untrue? I didn’t know then, and I don’t know now. But as I recall, I wrote a short story that I hope was as open-ended in a fifteen-year-old way and lent itself as much to individual interpretation as I have intended in my biographies of Elvis, Sam Cooke, and Sam Phillips, or any of the other books that I’ve written.

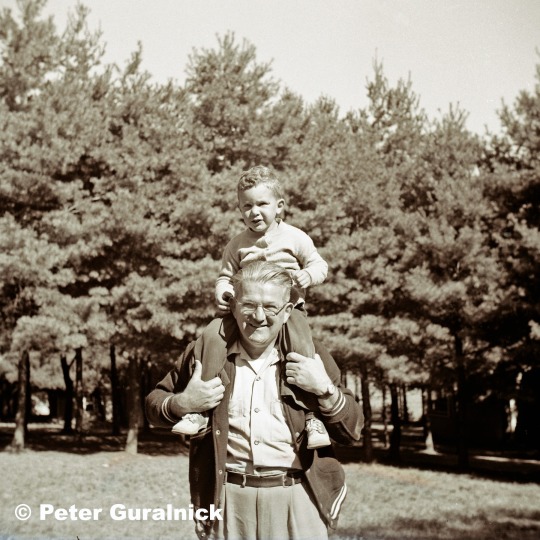

But there’s still that lingering question: what in the world would lead an eight or nine-year-old kid to want to be a writer – if he couldn’t be a be a Major League baseball player, that is. It was my grandfather, Philip Marson, who taught English for over thirty years at Boston Latin (no, not the same Latin School – it’s complicated), founded and ran Camp Alton (which I would later run) in what he conceived of as a fresh-air expansion of the educational experience, dreamed of having the time one day to finish Finnegans Wake (he finally did at seventy-eight, over his customary breakfast of shredded wheat), and explored the second-hand bookstores of Boston’s Cornhill for $.25 masterpieces like Jean Toomer’s Cane, without necessarily passing up a sidetrip to the Old Howard burlesque show in adjacent Scollay Square, where he pulled his hat down over his face for fear of running into one of his students. I wasn’t around for the Old Howard, which closed in 1953, but by the time I was ten or eleven I started accompanying him on his foraging trips to Cornhill (now the site of Government Center), which always included a mid-morning hot fudge sundae at Bailey’s, where the fudge sauce was so thick it could have been a meal by itself.

It was his enthusiasm, I think, that inspired me most of all, his enthusiasm and his unfettered appreciation for life, literature, sports (he was a three-sport athlete at Tufts – Tris Speaker, the Grey Eagle, he said, had praised him for his play in a college game at Fenway Park), grammatical niceties, and democratic ideals. More than just appreciation, it was his undisguised avidity for experience and people of every sort. “Hey, Pete,” he would shout out in his high-pitched voice, to my pre-adolescent, adolescent, and post-adolescent (does that count as adult?) embarrassment, “Will you look at that?” And I’m not going to tell you what that was – because it’s still embarrassing. But, you know, it was always interesting.

But none of that would have counted for anywhere near as much if he were not such an unrestrained fan of me – it just seemed like whatever I did was all right with him. He came to all my baseball games, naturally, but when I took up tennis, which he had always scorned as an artificially encumbered (don’t ask me why), pointless kind of sport, he embraced it wholeheartedly, coming to all my tournaments and swiftly learning the finer points of the game. If I recommended a book, he was quick to embrace it. And when at the age of eleven and twelve and into early adolescence, I suffered from fears that so crippled me that I found it difficult even to go to school, his belief in me never wavered. Or more to the point perhaps, he never seemed to see me as any less, or any different, a person.

I grew up in my grandparents’ house off and on from the time I was born. My father, whom I could cite as an equally inspiring influence in terms of both character and commitment, landed in England the day I was born and didn’t return from the War until I was more than two years old, nearly a year after V-E Day. So my mother and I camped out with my grandparents, very comfortably for me, though I’m not so sure about my mother. (One of the short stories I’ve written lately tries to imagine what it must have been like for her, twenty-three, twenty-four-years old, with no certainty of the future, an only child living with her only child in her parents’ house.) Then, when my father finally came home, we remained for another three years, until we could finally afford a place of our own, moving into the garden apartments that had recently opened up near-by as affordable housing for returning veterans. A year or two after that, my grandparents gave my parents the house and moved to a roomy old apartment in Coolidge Corner, not far away.

Staying with my grandparents on weekends in their new apartment, even more book-crammed than the house because it was crammed with the same books, was always a treat. We went to theater together, my grandmother, my grandfather, and I – I can remember seeing Charles Laughton in Don Juan in Hell, the stand-alone third act of George Bernard Shaw’s Man and Superman when I was nine or ten years old. (Shaw was always a great favorite of my grandfather’s, along with such native-born contrarians as H.L. Mencken.) We went to serious plays, musicals, Broadway try-outs, and revivals. Along with Shaw, Eugene O’Neill undoubtedly loomed largest in my grandfather’s theatrical cosmos, and it was as exciting to listen to my grandparents talk about seeing Paul Robeson make his Broadway debut in The Emperor Jones or attending O’Neill’s marathon nine-act Strange Interlude, which included a break for dinner, as it was to hear my grandfather tell the story of how he lost his hat when he stood up to cheer Franklin Roosevelt at the Boston Garden.

But it was books in the end that were the instigators of the most passionate discussions, books that inspired me to want to write books of my own, books that would always provide an impetus for dinner-time conversation and home décor. My grandfather introduced me to Romain Rolland’s Jean Christophe, to James Joyce and Knut Hamsun, Joseph Conrad and Ford Madox Ford (he loved to discourse on what he called the shuttle-and-weave of their narrative technique), and Sigrid Undset. I’ll admit, I might well have been better off if I had stuck a little longer with the Landmark series of biographies that continued to excite me or the Scribner Classics editions of Jules Verne and Robert Louis Stevenson and James Fenimore Cooper, with those wonderful N.C. Wyeth illustrations, or any of the other children’s classics that I had indiscriminately devoured. But I was so bereft of self-awareness (while at the same time so consumed by self-consciousness) that I started to record my impressions of each of the books that I read in little tablet notebooks, earnest summaries not just of the books but of my own judgments of them. I could only express my “wonderment at, and admiration for, the author’s scope and ability,” I declared, writing about Sigrid Undset’s Kristin Lavransdatter when I was fifteen. And struggled for six handwritten pages to express more specifically my admiration for this 1000-page trilogy that takes place in fourteenth-century Norway, with its rare combination of epic sweep and unexpected intimacy. My grandfather considered it the greatest novel ever written, a judgment with which, as you can see, I struggled mightily to concur – and in fact still do. But I also knew, as my grandfather’s own omnivorous passion for discovery suggested, that all such judgments were nonsense. In the end, like the question of who was the greatest baseball player of all time, an early and abiding conversation of ours, it was a provisional title only, waiting for the next great thing to come along.

And yet, and yet, well, you know, when it comes right down to it, it wasn’t books or writing or epistemological fervor that were my primary inspiration. They would have meant nothing if it hadn’t been for everything else. What my grandfather communicated to me most of all was a hunger for life, for the raw stuff of life that served as the underpinning for every great book that either of us admired. I’m oversimplifying, I know, but it just seemed like, in the greater scheme of things, with my grandfather there was no exclusionary gene. There was no sense of high and low (no one appreciated a “dirty joke” more shamelessly than he) and, save for the inviolable principles of grammar and the strict standards of a “good education,” everything was in play, everything existed on the same human plane.

In many ways, I think that was what opened me up to the blues – not just the music but the experience of the music, the many different implications of the music – which turned out to be the single greatest revelation of my life. So many of the places where I started out are still the places where I am. Books, writing, playing sports (sadly, no more baseball), the blues. As my grandfather got older, his enthusiasm never diminished. When $100 Misunderstanding, an alternating dialogue between a fourteen-year-old black prostitute and her clueless white college john, came out in 1962, my grandfather got the idea that he and I could write a novel in the same manner about the generation gap, which was very much in the news then. We would write alternate chapters – well, you get the picture – and he was so excited about the idea that I couldn’t say no, though we never advanced to the point where we put anything down on paper. When the draft briefly threatened, he decided he would buy land in Canada and we could start a commune there, and while the threat went away before he was ever able to put his idea into practice, I had no doubt it would have been a very interesting (and well-ordered) commune.

A few years later, in 1970, he asked if I would help him run camp the following year. I’m not sure I need to explain, but this came like a bolt out of the blue. Alexandra and I had been working at camp for the last few years, and I was running the tennis program and coaching baseball. “No speculation,” I told my twelve-year-old charges, taking my cue, as always, from William Carlos Williams. It was a wonderful way to spend the summer, and it was certainly rewarding from any number of points of view, not least of which was being close to my grandparents. But not for one moment had the thought of running camp crossed my mind. I was twenty-six-years-old, working on my first full-length published book, Feel Like Going Home, and my fifth unpublished novel, Mister Downchild, and I thought I knew where my future lay.

At the same time, the idea of turning my grandfather down never crossed my mind. He was seventy-eight years old and had never asked for my help before – in fact, I couldn’t remember him ever asking anybody’s help. So, sure, yes, unequivocally. And yet I found it impossible to imagine how this could ever work. How exactly was I going to help? And if his idea was to defer to me, to withdraw and leave the day-to-day running of camp to me, well, this would require a lot more conviction, self-belief, and, above all, knowledge (since no one knew anything about the running of camp except for him) than I possessed. The question was, did I have it in me to be the person that I needed, that I wanted, for my grandfather’s sake, to be?

As it turned out, I never had to answer that question. My grandfather got sick – it appeared at first to be a stroke, it turned out to be a brain tumor – almost immediately after asking for my help. I kept things going over the winter in hopes that he would recover, and when he didn’t, it was like being thrown into the water and discovering, much to your surprise, that you actually knew how to swim. I ended up running camp by myself that summer, and I ran it for twenty-one years after that, and whatever my grandfather intended (and I suspect it was a great deal more than just providing me with an income to support my writing), it turned out to be one of the most rewarding, existentially engaging experiences of my life. And not just in the ways you might expect – camp was a thriving, self-sustaining community of 300 people that continued to grow and evolve, as did my own views of democratic institutions and possibilities – but because it inescapably exposed me to real life, it forced me out into a world in which my feelings were not the center of everything. A world of building things and balancing books, where you dealt of necessity (and to your own incalculable experiential benefit) with all kinds of different people, benefited from the wisdom and experience of others (could that have been what Omar Pound meant?), and learned not just to stand up for yourself but for everyone else, because no matter how much inner turmoil you might feel (and I think back to my ten- and –eleven-year-old self, curled up in a ball reading a book, afraid to leave the comforting familiarity of my room), you don’t have the luxury of dwelling on your own emotions. Because – why? Everyone is depending on you. It forced me, in other words, to grow up, in a way that deeply affected not only my writing but my ability to understand all the different personalities and perspectives that I wanted to portray in both my fiction and my nonfiction, in my biographies and profiles of such multifarious personalities as Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Waylon Jennings, Sam Phillips, and Solomon Burke. It forced me, when it came right down to it, to embrace the world.

My grandfather used to come see me in my dreams sometimes. He always wore his tan windbreaker and stood by the tree on the right field line at camp, where he used to watch my games, both as a kid and as an adult. It was always good to see him – there was never a time I didn’t wish he would stay longer. But even though I rarely see him nowadays, I carry with me always the conviction that he communicated so unhesitantly: that everything is just out there waiting to be discovered. And I try to keep that belief in the forefront – well, maybe the backfront – of my mind. I continue to be drawn on by the prospect, I continue to struggle for its discovery.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

COLE SPROUSE | THE LAST MAGAZINE (30/1/2017).

When Riverdale, Greg Berlanti’s dark, contemporary take on the Archie comics, premiered on the CW last week, it marked the return of the actor Cole Sprouse to television in a project worlds away from the one that first brought him to prominence as a teenager. Sprouse and his twin brother Dylan are still best known for playing the titular brothers on Disney Channel’s The Suite Life of Zack and Cody and its follow-up The Suite Life on Deck, which took place, respectively, in a hotel and on a cruise ship and made the Sprouses the most famous television twins since Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen. Broadly humorous, loudly acted, and, as Sprouse politely puts it, “boisterous,” the shows fit neatly in the Disney stable alongside Hannah Montana, which starred a young Miley Cyrus, and Wizards of Waverly Place, which introduced Selena Gomez to the world. And just as Cyrus and Gomez have successfully managed to move beyond their child-actor days and reinvent themselves in recent years as international pop stars, Sprouse sees Riverdale as a chance to prove that his Disney phase is behind him. “I think while it’s easy to group us all into a similar category, all of our paths have remained unique,” he explains. “We end up having to show the same maturation, just in different ways. We’re consistently trying to prove our humanity to a group of people that has a really hard time believing it.”

Born in Italy, the Sprouse twins began acting as babies to help their mother pay the bills. They appeared in films like Big Daddy with Adam Sandler and as Ross’s son on Friends, and were tapped by Disney in 2005 to headline The Suite Life, which would go on to run for four years before spinning off as The Suite Life on Deck. “The show gave me a profound work ethic,” Sprouse says. “I never missed a day of work in the eight years I was there, and it really taught me to push myself and drive myself. But the danger of being on a show like that for eight years is that you lose purpose. Continuing the show is oftentimes the most dangerous thing to do as an actor because purpose is the currency for quality work as an actor.”

Besides the increasing monotony of playing Cody, Sprouse now says that he is still trying to sort out what being so closely linked to a fictional persona throughout his teenage years has meant for his personal development. “When you’re a child and you’re growing up and you’re mimicking a certain character or you’re trying to live and breathe a certain character on set for eight years that are also your formative years, you oftentimes take a lot of who you’re playing into your real life and kind of become that thing,” he explains. “You end up having to figure out where you separate from the thing you’ve played for eight years when you leave it.”

Sprouse, now twenty-four, says that the unique strictures and tone of the Disney studio also may have served to sharpen some of the developmental struggles its actors had to endure, due to the contrast between the roles they were playing onscreen and the people they were still in the process of become themselves. “Disney acting as a style is very large. It’s designed to capture the attention of children, so it often comes off as immature and youthful,” he says. “That gets complicated when you’re starting to develop personally and sexually through puberty and you’re starting to have these opposing ideas of yourself as a young person. Oftentimes that leads to some form of cognitive dissonance where you are being sold as something you truly don’t identify with and you have this rebellion that takes place.”

Having successfully made the transition from child star to grown-up actor without scandal, Sprouse is nonetheless quick to come to the defense of his peers who have had rockier paths, heightened by the intense scrutiny of the public eye. “It’s one of those things that gets written off as humorous when you watch a child entertainer try to redefine themselves, but it can be an intense identity crisis,” he says. “I think in our modern society we have a much greater understanding of the importance of personal identity and how we see ourselves and I’m hoping that over time people latch onto the fact that this hurts people and they have a little more respect for something like that.”

In lieu of “We Can’t Stop” or Spring Breakers, Sprouse turned to school. After taking a year off after The Suite Life, he enrolled at NYU at nineteen and eventually decided to major in archeology. Fascinated by the earth sciences since childhood thanks to a geologist grandfather, Sprouse jokes that he wanted to live out “tales of adventure,” which he was able to do after he was accepted into an exclusive program to work on an excavation site in France. He moved decisively away from acting during his four years as an undergraduate, and admits that he very seriously considered the possibility of never coming back. “When we were younger, it was a business choice for us and I realized that I couldn’t live like that anymore and there was no fulfillment in that sort of acting,” he explains. “I needed to take a break and reassess, and I did. My brother and I had sort of reached a plateau and there was nothing we could really do there so we chose to go into education and embrace an interdisciplinary world of knowledge.”

Faced with the choice between (expensive) graduate school and (relatively lucrative) television work, Sprouse says he decided last year to take a shot at pilot week, the annual busy period when studios and networks cast many of the new television shows they want to try out. “I was planning on continuing with archaeology, but when I auditioned and I got the part and we did that pilot, I had a lot of fun,” he recalls. “I didn’t really think of it, but it felt fulfilling again, which is really the only thing you should honestly pursue in art. And as long as it feels fulfilling, I’ll continue.”

Having just come off a Twilight Zone binge, Sprouse says he was immediately attracted to the role of Jughead, Archie’s best friend who also takes on a voiceover role in Riverdale that is reminiscent of Rod Serling’s narration for his influential television series. Full of sex, scandal, and the sort of heightened drama common to most shows about teenagers, Riverdale will come as a surprise to most people who know Archie only as a cheerful, lighthearted slice of midcentury small-town American life. The series opens with a death, Archie sleeps with his music teacher, and Veronica comes to town disgraced after her family loses all its wealth when her father is jailed for financial misdeeds. There are notes of Twin Peaks—although Sprouse is loathe to compare anything to David Lynch—and Brick, the 2006 Joseph Gordon-Levitt movie which took a film noir sensibility to high school life.

Sprouse himself admits to having been put off by the initial descriptions of the show, but says that further reading helped him understand that Riverdale fits easily into the world of Archie, as the new leadership at Archie Comics has pushed in new and surprising directions to make the brand relevant again today. “When I first heard the abstract, it kind of put a sour taste in my mouth,” he says. “I come from a comic background—I worked at a comic shop—and when you hear about a dark and gritty take on an otherwise beloved franchise, that’s all the wrong buzzwords for the right project. Nothing really dubious happens in the original Archie Digests, but as I started to do more research, I realized the universe of Archie is really wide open. The Punisher comes to Archie, Archie dies when he gets shot trying to protect his friend, and in the new comics, zombies come to Archie. So it seemed like the road had been paved for a while for something like this. My knowledge now is that the Archie universe is wide enough for something like this to take place.”

In refashioning an idyllic American icon for a confusing and complicated new world, Riverdale is also, Sprouse contends, a tacit reflection of today’s political climate. “We live in a society right now that’s obsessed with this golden-age America mentality,” he explains. “Trump’s whole campaign was built around ‘Make America Great Again,’ which essentially is a play towards the same era that Archie arose out of that is this golden, perfect world. I don’t mind how we may be tampering with this idea of a golden age because of my personal political stance. I don’t think that ‘everything is perfect and jolly’ is a perspective that makes any sense. Our society is either primed perfectly for a more contemporary view of this classic American property or they’re going to rebel against it. It’s the same political division within our society right now.”

Currently based in Vancouver shooting Riverdale, Sprouse is also continuing to pursue a photography career on the side. He’s been commissioned by Condé Nast Traveler and shot a story for Teen Vogue earlier this month, and says that what began as a hobby has quickly turned into a passionate vocation. He finds that the travel photography, especially, has been helpful in shaping his perspective. “Travel photography is difficult in that you’re very reliant upon the place you’re going to be a sort of beautiful that can sell,” he explains. “You end up having to be really critical and quite aware at all points of your environment. It’s a very different way of looking at the world, but you end up internalizing a lot of that way of seeing. Most of us were quite nomadic through human history, and I think that part of us still very much exists in a yearning for adventure and worldliness. What travel photography is aiming to do is to inspire a love of something different than yourself.”

And though they require work on different sides of the camera, what connects Sprouse’s acting and his photography is that he plans to continue both as long as they remain “fulfilling.” With over two decades of experience under his belt, he knows what he wants and he knows when it’s time to move on. “Riverdale is a much more human project than the last one and I realize now that though I’ve had enough time to step away and to take a breather, my main challenge if I’m going to continue acting is to discern the things that were valuable about my childhood and the skills I acquired as a child and the things to keep and the things to let go,” he says. “It’s more real, and I don’t think just because it’s on the forefront of pop culture that it should be treated any less than something very ‘noble.’ I’m going to try and do that and see how it ends up.”

84 notes

·

View notes