#Jim Mamer

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

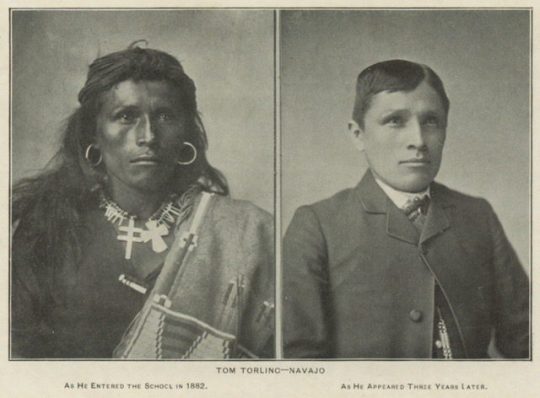

Missing Links in Textbook History: Colonialism

By Jim Mamer / Original to ScheerPost Editor’s Note: This marks the 12th installment in Jim Mamer’s “Missing Links” series. A former high school …Missing Links in Textbook History: Colonialism

View On WordPress

#American history#American Revolution#Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831)#colonialism#colonialists#control#indigenous peoples#Jim Mamer#Native Americans#slavery#trail of tears

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Missing Links in Textbook History: War

According to the Institute for National Strategic Studies: “The most highly prized attribute of private contractors is that they reduce troop requirements by replacing military personnel. This reduces the military and political resources that must be dedicated to the war.” By Jim Mamer , ScheerPost, 28 Mar 24 In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Jim Feast’s Long Day, Counting Tomorrow

1))) Why did you chose to write with a nonlinear structure? What does the novel gain as your characters move within time and space?

In looking over all my answers, I find I expressed much of what I have to say in answering this first question. So, bear with me, if the opening reply gets a bit long-winded.

I believe that Freud’s theory of over-determination, which holds that a dream image will only appear if it has multiple causes pressing it to come to life, also applies to novels. In the present case, my choice to work with a non-linear narrative was over-determined by precursors I esteem, the book’s structure and my philosophy.

Novelists (or at least those with pretensions) always give credit in their development to one of the greats of Modernism, whether Joyce, Kafka, Woolf or others. My allegiance is to Proust.

Those who remember the details of Remembrance of Things Past will recall that as the hero, Marcel, moves forward in time, he keeps thinking back to reinterpret or almost re-see the past. At his first visit to Balbec, he meets a crowd of young women, who pal around the seaside resort, members of the group becoming (to him) almost indistinguishable. Later, he singles out Albertine, and later yet the two become lovers and she moves in with him in Paris. However, by putting it this way, I misrepresent the book. Each of these forward movements is not only temporarily halted by the first person narrator as he thinks back to how new moments compare to those in the the past, but because, learning years later of things of which he was unaware going on at Balbec, he is forced, as it were, to remake the present in light of this new knowledge. One might say that in this book, no matter how long ago something happened, it is always in play.

This was the formative novel of my young manhood and it became something of a guiding star in all I wrote. This and one other book, a book that (given its literary merit or rather lack of same) is a bit embarrassing to name: Sue’s The Mysteries of Paris.

Compare this line from Long Day, Chapter 4, v.:

Time was Mac entered Billy’s Topless like a moody conqueror

To this line (in translation) from Book VI of Mysteries:

[As he entered Madame de Lucenay’s house] Never had the viscount been more glorious; never had he felt happier, more sure of himself, more the conqueror.

Sue’s ties the past to present in a way conventional to the times. Seemingly complete strangers feel themselves drawn to or repelled by each other via near occult sympathies, which, as it turns out, are really based on the fact that these strangers are long-lost daughters, fathers, brothers, and so on.

I fancy Long Day presents a materialist version of this theme. My characters are drawn together by similar mystical propensities, not due to family heritage but because they eventually find they belong to contiguous progressive and avant-garde groups, all of which have some relation to the now disbanded, shadowy Neo Phobes.

In any case, both these book influenced my thinking as did Long Day’s structure. There are two untoward elements here. 1)) Each chapter has one more section than the last. So Chapter 1 has 1 section; Chapter 2, two sections and so on. 2)) After the book gets underway on November 12, there begin to be two, forward, chronological thrusts: one going ahead from November 12, the other, starting in the past and moving toward it. So, eventually, the penultimate chapter, the first movement ends with the solving of the crime. The last chapter, following the second movement, ends on November 12 and shows how the hero’s life was saved so that he could then solve the crime.

(By the way, November 12 is my wife Nhi’s birthday.)

Perhaps the reason for the first innovation is obvious. The book opens with Rask writing in his diary, the solitary act of an isolated character. What takes place, chapter by chapter, as more sections are added, is that we find out to how many other people he is connected, each with its own dramas and projects. This indicates how tightly he is bound to a greater community, which is (I believe) best shown in all its reality by the nonlinear element. Through this, we find that not only is Rask tied vertically to community (in the sense that he meets will meet a new link that end up knowing others links he already knows), but he is tied horizontally to it – and this is very much taken from Proust – in that this new link has as-yet-unrecognized ties to his past, which can only be fully represented by returning to this past in flashback chapters.

Still, having read all this, someone may ask: Why fixate on how the character is shown to be horizontally and vertically embedded in a group context? What’s the point? What kind of non-starter theme is this?

To answer this, let me talk about my life, but not my life as an individual but as a group member. In the early 1990s, Carol Wierzbicki, Ron Kolm, Yuko Otomo, Bonny Finberg, Peter Lamborn Wilson, Michael Randall, Sparrow, Eve Packer, Tsaurah Litzky, bart plantenga, Deborah Pintonelli, Steve Dalachinsky, Samuel Delany, myself and others formed a literary group called the Unbearables. The idea was not to form another writers circle but a collective that would imitate the audacious exploits of the Situationists.

What did we do? We invaded the New Yorker’s offices and, until escorted out, demanded they print more poems about earthworms. We put on a Jack Kerouac imitators contest to offset the NYU Beat Conference. At our event, the aspirants not only had to read Mexico City Blues style poems but sit on the lap of Mamere (Ron Kolm in drag) to drink a shot of Jim Bean as well as panhandle the audience for spare change. Our point was not to protest the Beats but their commodification. And along with these spectacles, we put on nearly weekly readings, including such events as a séance at the Fusion Arts Gallery, complete with smoke machines and ghostly echoes, at which writers channeled departed writers. Michael Carter even came in a winding sheet, covered in dirt, as if he’d just pushed his way out of the grave. Add to that nearly 15 years of monthly get-togethers at the now gentrified-out-of-existence, dive bar, the Shandon Star, and you have a sense of the existence of this group.

Anyone who has read the newspaper in the past 15 years will have heard that community is on the way out. Now it’s every dog-eat-dog for her/himself. This is the corporate script, which supposedly even applies to the literary world, where the real author tramples all others on the way to the top of the heap. My experience runs counter to all this. What I’ve seen is that the deeper the artist is involved in a community, not only as a member but as a participant in scandalous behavior and inventive projects, the truer that creator’s art.

So, I got to thinking, maybe I could write a novel in which a character, at first seeming to be isolated and anomic, is shown, page by page, to be, both by time and situation, enclosed in a community of plots and counterplots, all of which coalesce in the end to save his life. Such a book would give the reader a deeper sense of what reality is or could be.

Indeed, as I saw it, this would translate Proust’s vision into postmodern embodiment terms. In Jameson’s famous formulation (in Postmodernism: The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism), Modernist novels often center on revealing a character’s hidden inner depths. So, Proust shows Marcel’s insight on the nature of time gradually taking shape through years of his life. Jameson continues that Postmodernist writing, by contrast, is all surface, with characters who are basically shallow, engaging in a non-directional fluctuations from fugue states of manic behavior to passivity. Take Slothrop in Gravity’s Rainbow as a marker here. But what if, I was thinking, the Postmodern person could be given depth in exteriority? Instead of a book gradually revealing the complexity of the person’s interior, it revealed the complexity of her or his exterior? It was worth a try, although it would only work, I thought, with a very disturbed chronology.

2)) Was this novel always conceived as a murder mystery? Why did you choose to tell a story about the AIDS epidemic with a mystery backdrop?

Good question. Now that I’ve said almost everything I have to say, let me simply outline a few points in relation to each very wisely posed question. As to the mystery form, I can identify two things that pushed me in the direction of making this a detective story,

First, let me ask: What is American detective fiction? Am I the only one that sees it falling into left and right wings? It’s epitomized by the iconic difference between Hammett and Chandler. Hammett, the disillusioned Pinkerton, thrown in jail for refusing to name names during an anti-Communist trial, versus Chandler, the laid off oil company executive who, for instance, in his racist depiction of L.A.’s Central Avenue in the opening of Farewell, My Lovely, earned him (from Chester Himes) the epithet, “a joker.”

In Zizek’s appreciation of Hammett, he says each of his five novels was totally distinct, each taking a different tack, driving in a different direction that Hammett would never subsequently repeated. I thought of that as an ideal way to write, a way taken up by Hammett’s only true disciple, the aforementioned Himes.

Imagine a mystery in which the plot is not centered on solving a crime but on showing why the crime cannot conceivably be solved. This is Himes’ Blind Man With a Pistol, in which the white captain sends out his only two black detectives to find out who started a Harlem riot. The book describes the neighborhood’s competing social movements, eccentric religious sects, impoverishment and the segregation blocking people’s opportunities. The book ends having revealed a crime (the riot) that has many extenuating circumstances but no culprit

How could it have one when it was caused, not by individual rabble rousers, but social conditions?

Or take the equally unusual production, The Big Gold Dream. Himes opens by depicting a street-corner preacher holding a revival. A congregant gets on the makeshift stage and tells the audience that last night as she slept she had a vision of money and gold. Then she collapses, seemingly dead. Five hustlers, listening in the crowd, then begin acts of violence-prone dream interpretation as they (rightly) surmise that the woman’s dream alludes to hidden real wealth.

Himes’ novels, which I read in college, alongside Proust, mined a deep vein of political protest while offering a bleak but powerful view of a community, showing me a form of radically experimental and committed literature operating inside a genre.

But let me turn to the circumstantial. As the Unbearables formed and began giving readings, and since we already had great writers to read (some of them coming along a little later), from Yuko Otomo to Carl Watson, Meg Kaizu, Thad Rutkowski, Bonny Finberg, Ron Kolm, Gabriel Don, and Jason Gallagher, I became the master of ceremonies, introducing the readers. Since the audience was made up of us and our friends, I felt it would be useless, in making an introduction, to list a reader’s (generally spurious) accomplishments, so I, instead, just made up stories about them or the reading.

Here’s an example opening from 1992:

As Steve Dalachinsky once said, “Ron, you can’t give your poetry book away free. No one will respect your book. Don’t you know that the more a person pays for a book, the more that person will feel committed to it.” In fact, Steve went on, “The more you pay, the more you read so as to get your money’s worth. So, if you pay $10, you will read a few pages. Pay $20 and you will read the whole book. Pay $30 and you’ll read it twice.”

Today, following this philosophy we are going to auction off our poems. The winner will get a private, one-to-one reading in our VIP room. And in order to whet your appetites, tonight each poet will read you, as a teaser, part of their poem, leaving out the juiciest passages. In my introductions, after naming the poet, I will simply slip you, free of charge, some of those forbidden lines which he or she will only fully unload on you if you win the bidding.

To jump ahead, when it came the time, years later in 1995, to put out our first anthology, Peter L. Wilson, of all people, suggested I do as I did in the introductions, that is, put in the margins of the book an introduction to the each writer combined with some narrative. I wasn’t sure how exactly to do this but I believe it was Steve Cannon, who suggested I make it a mystery story.

To quote myself again, here is the premise of the mystery that was used in the margins of our first anthology:

Carol Wierzbicki ran a profit-strapped detective agency situated in the South Loop. When the four of them … arrived in her office that morning …. She lounged back in her chair and polished off a tumbler of rock and rye. “Can I help you?” Carol is one of the editors of the National Poetry Magazine of the Lower East Side … “What kind of case is this?” Carol asked.

”Missing person,” said Deborah Pintonelli, taking out a damaged photo [taken from the stage] of the auditorium. “We want you to locate these 100 people.”

The intros to the authors in the book were made part of a mystery. These over-determining experiences, my background, my Unbearable practice, predisposed me to put my hopes in the mystery form as the best conveyor of all the themes which (as I see it) are proscribed from serious fiction.

3)) What do you think the role of literature and culture was in raising awareness of AIDS and bringing about research into the disease and compassionate care for those affected? Do you think that books made a difference in slowing the epidemic and saving lives?

The novel Eighty-Sixed by David Feinberg presents an informed account of an AIDS sufferer, who, as the disease progresses, sees how politicized and homophobic the medical establishmentis which drives him into activism. As you can guess, this book was an inspiration to me, but there’s another issue here. Eighty-Sixed was hardly a favorite of the public compared to, say, Irvine Welsh’s best-selling Trainspotting. I see these two novels as part of a war, turning on the difference between activist Feinberg, writing with the truth in view (in relation to AIDS) and Welsh (despite the other considerable merits of his book) spreading ignorant lies.

In the book I co-authored on AIDS -- forgive me for constantly quoting myself -- I said this about Trainspotting:

I label the author’s Welsh’s ideas about AIDS cockeyed in light of such incidents as those presented in the chapter “Bad Blood.” There a woman becomes infected with HIV after one night, one “shag” they call it, with an infected man who rapes her. Next the narrator becomes infected after on night with her. If, as we discussed earlier, the likelihood of the first infection is one in a million, [one generally gets HIV only after multiple contacts with the infected] the likelihood of the second – one-shot, female to male transmission [female to male is very atypical, it is generally male to female] – is more like one in 2 million.

The point I’m making, one documented at length in the mentioned book, AIDS: A Second Opinion, is that the arts community, not the one producing best-sellers, but the one in the margins, was fighting not only to raise awareness of the disease and call for compassionate care, but battling the negative, panic-inducing misconceptions promulgated in the mainstream.

Moreover, in the 1980s, as literary activists were fighting the combined complacency or indifference of the public, the government, and the corporate medical industry, it is important to recognize that the marginal arts community became integrated as part of a broader community in struggle. I give a thumbnail of this as it was visible in San Francisco:

If we look at the case of San Francisco in the early days of the crisis, we see that the gay community developed a mesh of dispersed organization. … Some of the major components of this distribution were the Shanti Project, which acted as a counseling agency; the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, which arranged medical treatments; the group behind the AIDS Candlelight March, which raised public awareness while memorializing those that had passed; Project Inform, which studied and disseminated knowledge about drug treatments; Open Hand, a food service for PWAs, and SANE (Stop AIDS Now or Else), an ACT UP style group that engaged in public protest, such as blocking the Golden Gate Bridge [as well as having an affiliated arts group that worked to raise consciousness].

To summarize, as I see it, writers and cultural workers not only joined in the good fight of alerting, informing and arousing; but went further by creating their own groups and then linking up with other organizations who had joined the battle to increase knowledge and care for those hit by the AIDS plague.

4)) What do you think makes the book readable and enjoyable, although it’s about corruption and evil and people dying of a terrible disease?

To answer this question let me begin with what will seem a rather out-of-left-field way by saying something about the Dadaists. As I understand them, gathered in Switzerland while an insanely destructive world war was going on in Europe, they felt the times demanded a different kind of art, one more rule-breaking and impolite, as an adequate response to the horrors all around.

On a lower plane, the Unbearables felt, as we stated and re-stated in our get-togethers, that – although there were outstanding exceptions, such as Barbara Kingsolver, Jonathan Lethem, Carolyn Chute and Paul Beatty – as a whole the literature of our time was compromised. Perhaps, it was due to the ever-growing stranglehold of corporate publishing, but overall literature was not facing up to the social problems of our time. (Compare Proust’s confrontation of anti-Semitism and open discussion of homosexuality or Sue’s look at poverty.)

This doesn’t mean that in response the Unbearables wanted to produce political pamphlets, thought there were a few of those too, but they sought to create a literature of enjoyable texts, but ones that refused to shy away from America’s monumental failings.

Let me mention a few strategies other group members adopted to talk about harsh situations while using “gimmicks” to produce an exciting reading experience, taking up some books published by the renegade, saintly Jim Fleming of Autonomedia. Black writer John Farris talks about his bleak time in prison, but in a transmuted way. In The Ass’s Tale he did so by describing his hero as magically transformed into a dog, placed in a penitentiary run by a passel of talking monkeys, mastiffs and other animal low-lifes. Bonny Finberg in Kali’s Day describes a woman who goes to Nepal to seek enlightenment, but this is no New Age yuppie, rather a fleeing pot dealer, escaping both the law and her kinky ex-boyfriend. Finberg’s sensitivity to the Eastern country, the character’s comic, absurdist misadventures, and loopy spiritual wisdom embodied in the book make it a tremendous reading experience, despite its low down milieu. Finally, Ron Kolm, in The Plastic Factory, takes the most unpromising of experiences, a guy’s first day on the job making plastic, and uses matter-of-fact deadpan humor and sly observations to make this a book to look at once and then read again.

My own effort in Long Day to describe a hero coming apart under the double diagnosis of AIDS and cancer, who finds (and, hopefully, the reader finds also) a healing leaven of gallows humor along with a waxing sense of the loving support that can arise in a marginalized community forced to take care of each other when they ignored by most of society’s helping institutions.

5)) A reviewer has commented that hero Rasken Hasp is realistic in that he has all sorts of random human things on his mind even though he knows he doesn’t have long to live, that big existential thoughts aren’t all he thinks about. Would you agree with that? Have you known someone who was near death? What do you think people really think about in their last months?

I heartily agree with the reviewer’s observation that Rask seems to be too busy worrying about other things to contemplate his approaching demise.

This novel is dedicated to long-time friend John Penn, boyfriend of my editor, Carol Wierzbicki; Unbearable member and dying man. A lot of Rask’s character and history is drawn from John, who had AIDS and cancer, probably brought on by a crack and cocaine addiction, that he broke through attendance at AA. He was a guy who thought each day’s hat selection was crucial to his well-being.

Now, to seemingly digress, I feel it’s hard to truly know someone unless that person is an artist, because an artist you can understand by triangulation. When I got to know a writer, say, Carol, I began to see and talk to her, that’s one part; but then I heard her read her writings, and that gave me the other side. In most cases, there’s no easy fit between the two revealed selves and lining them up allows you to see into the puzzle that is each person.

Now John Penn had an outsized, brash, in-your-face personality, but this character was humbled down (in a good way) in his writing. His prose was deeply observant, unobtrusive, with a linguist’s feeling for words and a scat singer’s ability to play with them. So, taking the two sides, it was as if I saw him raw and cooked.

In his last days on earth, I felt that his writing was taking (in a good way) more from his brash side. I don’t mean he lost something, as if death were releasing some of his “uncouthness” into his writing, but rather that he was becoming more integrated. As his writing changed, he changed and some of the modesty of his writing also became part of his humanity.

You know I knew him before he cleaned up when he was not one for following the rules. But he made a change, had to change, when he entered AA. It was a heroic struggle, giving up drinking and drugging was a struggle, which he won. I hope this book reflects some of his courage, some of his hardihood.

Jim Feast’s Long Day, Counting Tomorrow is available here.

0 notes

Text

Smelly Flowerpot Takeover 140817

Two hours of music that might be a little different to the usual... Damaged Bug - Bog Dash Jim O’Rourke - All Downhill From Here Bonnie Prince Billy - Haggard (Like I’ve Never Been Before) Songs: Ohia - I’ve Been Riding With The Ghost Slowdive - Star Roving Spoon - Pink Up Loose Fur - Laminated Cat Sue Garner & Rick Brown - Asphalt Road 75 Dollar Bill - Beni Said Mamer - Blackbird Troupe Maijidi - Afriquiya Loscil - Red Tide 23 Hanging Trees - L’Instant Luke Abbott - The Balance Of Power Boris - Absolutego Mammoth Weed Wizard Bastard - Valmasque Endless Boogie - High Drag, Hard Doin’ C Joynes - World of Kobu Download here.

1 note

·

View note

Quote

Take, for example, what comes from an increasingly shrill conservative chorus. After eliminating most of the usual suspects, the source of our fiscal problem becomes pretty simple. Our debts can’t be the cumulative result of multiple tax cuts. The crisis has nothing to do with our ongoing, unnecessary and counterproductive wars. It can’t be the fault of the bankers and brokers who defrauded millions with securitized debt obligations based on bundling large numbers of “liars’ loans.” It probably has nothing to do with our failure to tax most Internet sales, and it certainly can’t be because hedge fund managers are allowed to treat a portion of their income as capital gains. Instead, the cause identified by most Republican governors, legislators and pundits is simple; government spends too much, and a lot of the blame falls on the public service unions. Indeed, at the recent Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) in Washington, D.C., one panel was titled “Bleeding America Dry: The Threat of Public Sector Unions.” That’s right: The firefighters, the police and the teachers are bleeding the country dry.

An inspiring former teacher of mine takes on anti-union sentiment in Truthdig.

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Missing Links in Textbook History: War

According to the Institute for National Strategic Studies: “The most highly prized attribute of private contractors is that they reduce troop requirements by replacing military personnel. This reduces the military and political resources that must be dedicated to the war.” By Jim Mamer , ScheerPost, 28 Mar 24 In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

0 notes