#Jehanne d’Évreux

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#house of lancaster#house of Navarre#house of Brittany#Joan of Navarre#Queen Joan#Joanna of Navarre#Queen Joanna#Jehanne d’Évreux#Plantagenet dynasty#Valois dynasty#house of valois#maison des valois#Henry IV#John V#Lancastrian edit#Lancastrian consort#queen of England#medieval England#naomi watts#Jodi comer

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Favorite History Books || The Capetians: Kings of France 987-1328 by Jim Bradbury ★★★★☆

It was luck as well as judgement that the Capetians produced such a long line of competent kings. It required a certain amount of effort; each king had to marry, choose a suitable wife, and produce an effective heir. One or two Capetians left their marriages a little late but all succeeded in this modest effort. In the Middle Ages producing enough children to ensure an heir was a chancy business; many families failed in a very short space of time. Stillborn children, infant deaths, early deaths, fatal illness, fatal accidents, death in war - the possibilities were many, and survival into mature years by no means certain. Some Capetian kings did not live to have long reigns, but in general their survival rate was good and minorities were rare. The Capetians did their best to protect their heirs but they were also fortunate. The quality of a man that would make a competent king was another matter. Kings could do little about this beyond choosing a capable wife. Again the Capetians were remarkably fortunate. Compared to other dynasties the mental ability, common sense and general competence of the dynasty was evenly spread. There was no King John, Henry III, Edward II, Henry VI or Charles VI. One must recognize through the earlier period the importance attached to succession by the oldest son. The importance of this can be seen by comparing the Merovingian, Carolingian, and imperial practice.

In France, kings made a great point of organizing the succession for the oldest son, known as association, and it worked. It was invariable practice by all the Capetians from Hugues Capet, who associated Robert the Pious in the very year that he himself became king. The deed of association meant that the son was made king before his father died, thus validating the future succession. By the time of Philippe Auguste it had become so accepted, and the dynasty so well established, that association was no longer necessary.

The endurance of the dynasty was important. Comparison with the Holy Roman Empire makes the point. In the German case families failed to retain the crown and impose sons. The result was “election” of the new emperor, in practice a move to the strongest candidate from any of the principalities, or just as often the weakest candidate as the only one all the others would accept. The result was a series of disputed successions, lack of continuity and of stability. The relative growth of France as a power and the decline of the Holy Roman Empire through the Middle Ages owed much to the practice of succession. The family loyalty of the Capetian dynasty was another important factor. Rebellions by one member of the family against another were not unknown but they were rare. The comparison with other dynasties is telling, as the almost constant problems in this respect of the Merovingians and the Carolingians, of the civil wars in Germany or England. The granting of apanages helped this process, but there was also a strong family tradition, and nearly all younger brothers and close relatives were loyal and assisted the king of the day. As a result the reputation of the dynasty for good government stood high. Good and competent rulers were the mainstay of the dynasty - men such as Hugues Capet, Robert the Pious, or Louis VI. Philippe Auguste and Philippe IV were outstanding rulers in their own ways, while St Louis became an icon of medieval kingship throughout Christendom.

On 1 February 1328 the last Capetian monarch, Charles IV, died. The only survivors of the dynasty were female. His widow was pregnant and there was a period of uncertain waiting. On 1 April (appropriately?) she gave birth to a daughter. Recent development had excluded female succession, and it was ignored in 1328 - though some compensation was made to the surviving women of the family. The opinion of the nobles of France counted most, and they preferred Philippe de Valois as king. He became Philippe VI (1328-50) and initiated another long line of kings to 1589. They belonged to the same family as the Capetians but direct succession from father to son or brother had been broken. Philippe was the son of Philippe IV’s brother, Charles de Valois, and grandson of the Capetian Philippe III. Philippe VI was crowned at Reims on 29 May 1328.

One legacy of the dynasty was this stress upon excluding female succession, practice rather than law. The so-called Salic Law was suddenly discovered resting in the library of St-Denis in the 1350s. The uncertainty resulted in some dispute over the succession. Female members were compensated. Jehanne received the kingdom of Navarre; her son, by Philippe d’Évreux, was Charles “the Bad” of Navarre. Others received considerable cash payments. The female who created the most serious problem was Isabelle, daughter of Philippe IV, wife of Edward II of England and mother of Edward III - who in time made a claim to the French throne. It is true that this was only in response to Philippe VI claiming the confiscation of Gascony, but its consequences were great - though as an excuse rather than a reason perhaps. It initiated the Hundred Years’ War with all its horrors and instability for France. But it seems more a result of the rule of the Valois than a consequence of Capetian failure.

The Valois dynasty makes a contrast to the Capetian. Their defeats were more fundamental, notably in the war with England - at Crecy, Poitiers and Agincourt. No Capetian king had suffered such disastrous losses - King Jehan II was taken prisoner at Poitiers in 1356 and incarcerated in London. A notable point about the Capetians was continuity. One after the other the Capetians were able, competent men. They may not have been great intellectuals but they were mostly pious, hard working, and generally respected. The Valois kings were less fortunate. The unfortunate consequences of the accession of the mentally unstable Charles VI can hardly be exaggerated.

Not all matters Capetian continued to dominate. Perhaps deliberately, the Valois set some new values and changed certain aspects of rule. The Capetians had supported and raised the abbey of St-Denis as the royal abbey, and St Denis as the patron saint of France. The Valois did not exactly attack or destroy this, but they made a change. They placed more emphasis on St Michael, who became the patron saint for their dynasty, and then for France. They also replaced the oriflamme as the royal standard by the banner of St Michael. The same kind of comment could be made for all the troubles in later medieval France. They were hardly consequences of Capetian rule. Perhaps the greatest problems came from natural disasters. The late Capetian period had seen the beginnings of this trouble with bad weather followed by poor harvests, and plague. These problems increased under the Valois, particularly with the Black Death and its dreadful social and economic results - decline in population and social upheaval. Capetian times began to look like a golden age in French history.

#historyedit#litedit#house of capet#medieval#french history#european history#history#history books#nanshe's graphics

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moodboard: Henry IV, King of England, & his consort, Queen Joan of Navarre.

#plantagenet edit#lancaster edit#moodboard#henry iv of england#king henry iv#king henry iv of England#henry iv#house of lancaster#plantagenet dynasty#henry of derby#Joan of Navarre#queen Joan#queen Joan of England#queen Joanna of England#Joanna of Navarre#Jehanne d’Évreux#Jehanne de Navarre#Duchesse de Bretagne#Duchess of Brittany#Henry x Joan

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moodboard: Jehanne d’Évreux, fille de Navarre, duchesse de Bretagne et reine d’Angleterre.

#house of lancaster#jehanne de navarre#Jehanne D’Évreux#Joan of Navarre#queen Joan#plantagenet dynasty#House of Navarre#plantagenet edit

1 note

·

View note

Text

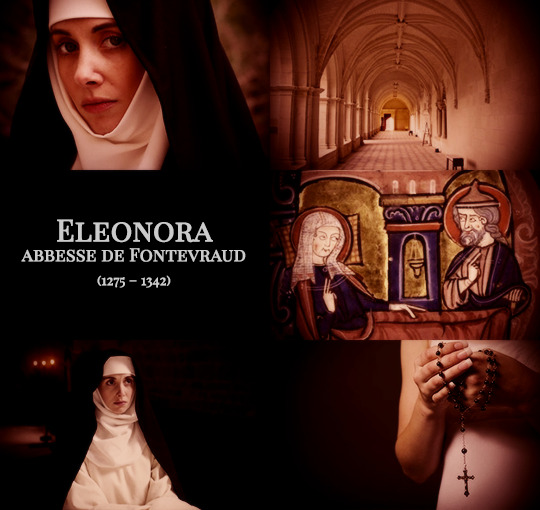

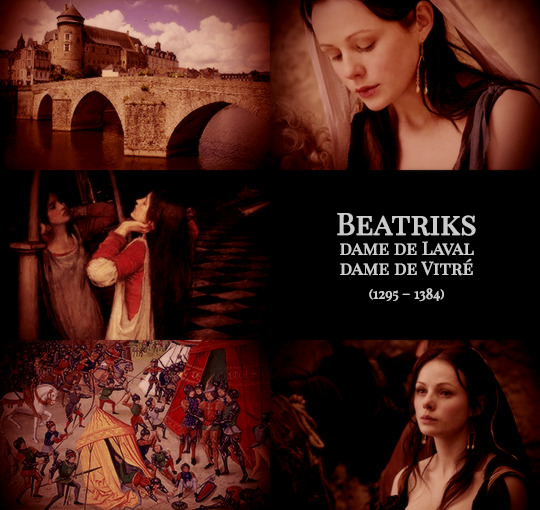

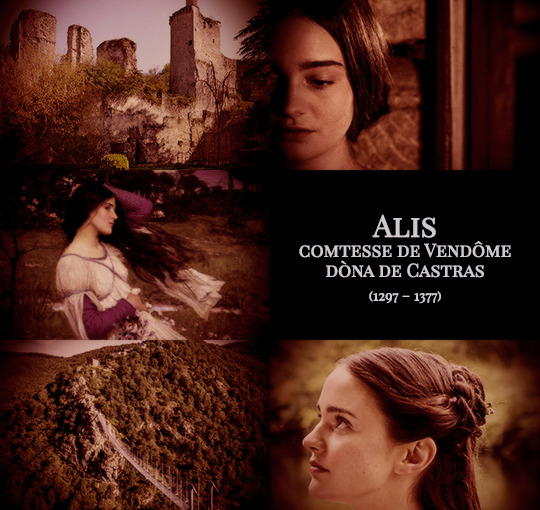

Daughters of the Breton Dukes, part II

Mari, comtesse de Saint-Pol. Daughter of Yann II, dug Breizh and Beatrice of England, Countess of Richmond. Mother of Mahaut de Châtillon, comtesse de Valois; Beatrice de Châtillon, dame de Crèvecœur; Isabeau de Châtillon, dame de Coucy; Marie de St Pol, Countess of Pembroke; Éléonore de Châtillon, dame de Granville; and Jehanne de Châtillon, dame de Maisy.

Blanche, dame de Conches. Daughter of Yann II, dug Breizh and Beatrice of England. Mother of Marguerite d’Artois, comtesse d’Évreux; Jehanne d’Artois, comtessa de Fois; Marie d’Artois, Markgrafin van Namen; and Jehanne d’Artois, comtesse d’Aumale.

Eleonora, abbesse de Fontevraud. Daughter of Yann II, dug Breizh and Beatrice of England.

Beatriks, dame de Laval. Daughter of Arzhur II, dug Breizh and Yolande de Dreux. Mother of Catherine de Laval, dame de Villemomble,

Janed, dame de Cassel. Daughter of Arzhur II, dug Breizh and Yolande de Dreux. Mother of Yolande de Flandre, comtesse de Bar.

Alis, comtesse de Vendôme. Daughter of Arzhur II, dug Breizh and Yolande de Dreux. Grandmother of Catherine de Vendôme, comtesse de La Marche.

Janed, dugez Breizh. Daughter of Guy VII, kont Pentevr and Jehanne d’Avaugour. Mother of Marc’harid Bleaz, comtesse d’Angoulême and Mari Bleaz, duchesse d’Anjou.

Janed, Baroness Drayton. Daughter of Yann Moñforzh and Jehanne de Flandre, dugez Breizh.

Marc’harid Bleaz, comtesse d’Angoulême. Daughter of Janed, dugez Breizh and Charles de Blois.

Mari Bleaz, duchesse d’Anjou. Daughter of Janed, dugez Breizh and Charles de Blois. Grandmother of Marie d’Anjou, reine de France and Yolande d’Anjou, comtesse de Montfort. Great-grandmother of Yolande d’Anjou, duchesse de Lorraine and Marguerite d’Anjou, Queen of England.

#historyedit#house of dreux#bretoned#medieval#french history#european history#women's history#history#royalty aesthetic#nanshe's graphics

63 notes

·

View notes

Photo

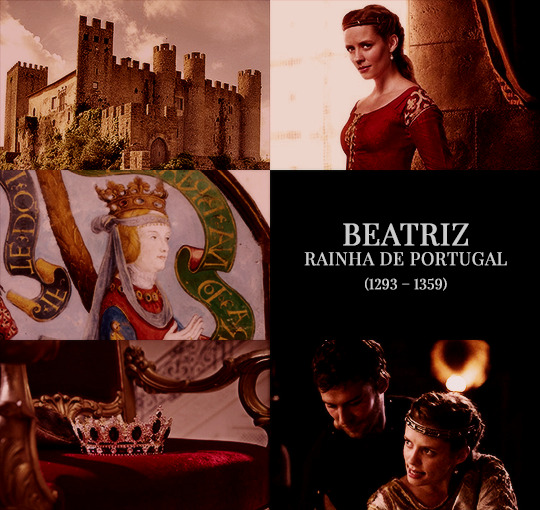

Castilian infantas aesthetic, part II

Leonor, queen of England and comtesse de Ponthieu. Daughter of Fernando III and Jehanne de Dammartin, comtesse de Ponthieu. Mother of Eleanor of Windsor, comtesse de Bar; Joan of Acre, Countess of Hertford; Margaret of Windsor, Hertogin van Brabant; Mary of Woodstock; and Elizabeth of Rhuddlan, Countess of Hereford.

Beatriz, marchesa del Monferrato. Daughter of Alfonso X and Violant d’Aragó. Mother of Violante degli Aleramici di Monferrato, Byzantine Empress.

Violante, señora de Vizcaya. Daughter of Alfonso X and Violant d’Aragó. Mother of María Díaz de Haro, señora de Tordehumos.

Beatriz, rainha de Portugal. Daughter of Sancho IV and María de Molina. Mother of Maria de Portugal, reina de Castilla and Leonor de Portugal, reina d’Aragó.

Leonor, reina d’Aragó. Daughter of Fernando IV and Constança de Portugal.

Constanza, Duchess of Lancaster. Daughter of Pedro I and María de Padilla. Mother of Catherine of Lancaster, reina de Castilla.

Isabel, Duchess of York. Daughter of Pedro I and María de Padilla. Mother of Constance of York, Countess of Gloucester.

Leonor, reine de Navarre and comtesse d’Évreux. Daughter of Enrique II and Juana Manuel. Mother of Joana Nafarroakoa, comtessa de Fois; Zuria I.a Nafarroakoa; Elisabet Nafarroakoa, comtessa d’Armanhac; and Beatriz Nafarroakoa, comtesse de La Marche. Grandmother of Zuria II.a Nafarroakoa and Leonor I.a Nafarroakoa.

María, reina d’Arago and regina de Sicilia. Daughter of Enrique III and Catherine of Lancaster.

#house of ivrea#medieval#house of trastamara#historyedit#spanish history#european history#women's history#nanshe's graphics#royalty aesthetic

163 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Navarrese infantas, part II

Joana I.a, Nafarroako erregina and reine de France. Daughter of Henrike I.a and Blanche d’Artois. Mother of Isabelle de France, Queen of England. Grandmother of Joana II.a, Nafarroako erregina; Jehanne III, comtesse de Bourgogne; Marguerite Ire, comtesse de Bourgogne; Isabelle de France, dauphine du Viennois; Blanche de France, duchesse d’Orléans; Eleanor of Woodstock, hertogin van Gelre; and Joan of the Tower, Queen of Scots.

Joana II.a, Nafarroako erregina. Daughter of Luis I.a and Marguerite de Bourgogne. Mother of Joana; Maria, reina d’Aragó; Zuria, reine de France; Ines, comtessa de Fois; and Joana, vicomtesse de Rohan.

Maria, reina d’Aragó. Daughter of Joana II.a and Philippe, comte d’Évreux. Mother of Constança d’Aragó, regina di Sicilia and Joana d’Aragó, comtessa d’Empúries. Grandmother of Maria, regina de Sicilia.

Zuria, reine de France. Daughter of Joana II.a and Philippe, comte d’Évreux. Mother of Jehanne de France.

Ines, comtessa de Fois. Daughter of Joana II.a and Philippe, comte d’Évreux.

Joana, dugez Breizh and Queen of England. Daughter of Karlos II.a and Jehanne de France. Mother of Mari Breizh, duchesse d’Alençon.

Joana, comtessa de Fois. Daughter of Karlos III.a and Leonor de Castilla.

Zuria I.a, Nafarroako erregina. Daughter of Karlos III.a and Leonor de Castilla. Mother of Zuria II.a and Leonor I.a.

Beatriz, comtessa de La Marcha. Daughter of Karlos III.a and Leonor de Castilla. Mother of Éléonore de Bourbon, duchesse de Nemours.

Elisabet, comtessa d’Armanhac. Daughter of Karlos III.a and Leonor de Castilla. Mother of Maria d’Armanhac, duchesse d’Alençon; Alienòr d’Armanhac, princesse d’Orange; and Elisabet d’Armanhac, dòna de Quate-Vaths.

#house of blois#medieval#house of capet#house of evreux#historyedit#spanish history#french history#european history#women's history#history#royalty aesthetic#nanshe's graphics

66 notes

·

View notes

Photo

WOMEN’S HISTORY † JOHANNA, HERTOGIN VAN BRABANT (24 June 1322 – 1 November 1406)

Johanna van Brabant was probably the eldest of the children of Jan III van Brabant and Marie d’Évreux, daughter of Louis de France, comte d’Évreux and Marguerite d’Artois. Her father, on the other hand, was a grandson of Edward I of England and Leonor de Castilla, through his mother, Margaret of Windsor. Johanna’s parents were also second cousins as Marie’s paternal grandmother, Maria van Brabant, was the younger sister of Jan’s grandfather, Jan I van Brabant. In 1334, Johanna married Willem IV van Holland, the only son of Guillaume II de Hainaut and Jehanne de Valois and brother of Marguerite II and Philippa de Hainaut. Originally, during the Hundred Years’ War, Johanna’s father had been allied with the English and had intended to arrange for Johanna’s younger sister, Margaretha, to marry Edward the Black Prince, but the alliance unraveled and instead Margaretha married Louis II, comte de Flandre, whose people had tried to force him to marry the Black Prince’s sister, Isabella.

Meanwhile, Johanna’s husband, Guillaume, died in the Battle of Warns on 26 September 1345. They had been childless, so Holland and Hainaut both passed to his sister, Marguerite. In 1352, Johanna married a second time to Wenzel I. von Luxemburg, the only son of Johann der Blinde von Luxemburg by his second wife, Béatrice de Bourbon. Around this time, both of Johanna’s surviving brothers died, forcing her father to recognize her as his heir. However, Johanna’s brother-in-law, Louis II de Flandre, disagreed about the succession and invaded Brabant in 1356. Johanna and Wenzel were at first forced to sign over Antwerp to Louis but later managed to repel him with the help of Wenzel’s half-brother, Holy Roman Emperor, Karel IV. Afterwards, Wenzel developed a feud with Wilhelm II., Herzog von Jülich originally over mercenaries robbing Brabançon merchants in Jülich. Wenzel invaded Jülich, but Wilhelm allied with his brother-in-law, Eduard van Gelre (younger son of Reinald II van Gelre and Eleanor of Woodstock), and defeated Wenzel at the Battle of Battle of Baesweiler on 22 August 1371. Wenzel was captured and held prisoner for 11 months, which did nothing for Brabant. He died in 1383, possibly of leprosy, and was buried in Orval Abbey.

Johanna’s marriage to Wenzel had also failed to produce surviving children and her nearest relative was her niece, Marguerite III, comtesse de Flandre, so it was agreed that Brabant would pass Marguerite’s second surviving son, Antoine. Johanna died 1 November 1406 and was buried in Brussels though her tomb was not constructed until the 1450s by Philippe le Bon de Bourgogne, who have may have erected it as propaganda to symbolize his claims to Brabant.

#joanna of brabant#house of flanders#medieval#house of luxembourg#dutch history#belgian history#european history#women's history#history#women's history graphics#nanshe's graphics

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

WOMEN’S HISTORY † BLANCHE DE NAVARRE, REINE DE FRANCE (1330 – 5 October 1398)

Blanche de Navarre (also known as “Blanche d’Évreux” and “la Belle Sagesse”) was the third daughter of Philippe d’Évreux and Jehanne II de Navarre. Her father died in 1343 while on Crusade in Castilla. Initially, there were plans for Blanche to marry the future Pedro I de Castilla and for her sister, Marie, to marry Pere IV d’Aragó, but Blanche’s marriage proposal fell through. Instead, it was arranged that she would marry the future Jehan II de France, whose first wife, Jitka Lucemburská, had died during the Black Death. Shortly before Blanche left to marry, her mother died of plague on 6 October 1349. After Blanche’s arrival in France, she utterly captivated her intended father-in-law, Philippe VI (who had also lost his first wife to the Black Death) and decided to marry Blanche himself, which they did on 29 January 1350. The marriage was not well-received by Philippe’s son, Jehan, or by most of the French nobility. Philippe died seven months later, in August 1350, leaving Blanche pregnant. Blanche gave birth to a daughter, Jehanne, in May 1351 and later resided in Normandy. Her hand in marriage was sought by Pedro I de Castilla, but she refused saying that French queens never remarried. In 1371, young Jehanne was betrothed to the future Joan I d’Aragó, but died suddenly in Béziers on her way to Aragon. Joan blamed her death on the Aragonese royal midwife, Bonanada, by way of sorcery, but his parents resolutely protected her from his wrath. Blanche lived most of her life in Normandie, but periodically visited the French court. During the Hundred Years' War, she often acted as mediator between her younger brother, the notorious Charles II of Navarre, and the French kings, Jehan II and Charles V. Blanche was most famously present when Elisabeth von Bayern arrived in Paris to marry Charles VI de France. Blanche died 5 October 1398 and was buried next to her daughter in the Basilica of St Denis.

#blanche of navarre#house of evreux#house of valois#spanish history#french history#european history#women's history#history#women's history graphics#nanshe's graphics#medieval

18 notes

·

View notes