#Jacob's line delivery → where's his oscar!!!

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Interview With The Vampire 1.03 Is My Very Nature That Of A Devil

#interview with the vampire#cinematv#filmtvcentral#userthing#smallscreensource#chewieblog#userstream#dailyflicks#usersource#tvarchive#Jacob's line delivery → where's his oscar!!!#lestat is a sopping wet cat here lmao#loustat

664 notes

·

View notes

Text

Once Upon a Time in America Is Every Bit as Great a Gangster Movie as The Godfather

https://ift.tt/38Ku8cF

This article contains Once Upon a Time in America spoilers.

The Godfather is a great movie, possibly the best ever made. Its sequel, The Godfather, Part II, often follows it in the pantheon of classic cinema, some critics even believe it is the better film. Robert Evans, head of production at Paramount in the early 1970s, wanted The Godfather to be directed by an Italian American. Francis Ford Coppola was very much a last resort. The studio’s first choice was Sergio Leone, but he was getting ready to make his own gangster epic, Once Upon a Time in America. Though less known, it is equally magnificent.

Robert De Niro, as David “Noodles” Aaronson, and James Woods, as Maximillian “Max” Bercovicz, make up a dream gangster film pairing in Once Upon a Time in America, on par with late 1930s audiences seeing Humphrey Bogart and James Cagney team for The Roaring Twenties or Angels with Dirty Faces. Noodles and Max are partners and competitors, one is ambitious, the other gets a yen for the beach. One went to jail, the other wants to rob the Federal Reserve Bank.

Throw Joe Pesci into the mix, in a small part as crime boss Frankie Monaldi, and Burt Young as his brother Joe Monaldi, and life gets “funnier than shit,” and funnier than their more famous crime films, Goodfellas and Chinatown, respectively. Future mob entertainment mainstays are all over Once Upon a Time in America too, and they are in distinguished company. This is future Oscar winner Jennifer Connelly’s first movie. She plays young Deborah, the young girl who becomes the woman between Noodles and Max, and she even has something of a catch-phrase, “Go on Noodles your mother is calling.” Elizabeth McGovern delivers the line as adult Deborah.

When Once Upon a Time in America first ran in theaters, there were reports that people in the audience laughed when Deborah is reintroduced after a 35-year gap in the action. She hadn’t aged at all. But Deborah is representational to Leone, beyond the character.

“Age can wither me, Noodles,” she says. But neither the character nor the director will allow the audience to see it beyond the cold cream. Deborah is the character Leone is answering to. She also embodies the fluid chronology of the storytelling. She is its only constant.

The rest of the film can feel like a free fall though. Whereas The Godfather moved in a linear fashion, Once Upon a Time in America has time for flashbacks, and flashbacks within flashbacks, and detours that careen between the violent and the quiet. It’s a visceral experience about landing where we, and this genre, began.

Growing up Gangster

Both The Godfather and Once Upon a Time in America span decades; it’s the history of immigrant crime in 20th century America. But they differ on chronological placement. Once Upon a Time is set in three time-frames. The earliest is 1918 in the Jewish ghettos of New York City’s Lower East Side.

Young Noodles (Scott Tiler), Patrick “Patsy” Goldberg (Brian Bloom), Philip “Cockeye” Stein (Adrian Curran) and Dominic (Noah Moazezi), are a bush league street gang doing petty crimes for a minor neighborhood mug, Bugsy (James Russo). New on the block, Max (Rusty Jacobs) interrupts the gang as they’re about to roll a drunk, and Max makes off with the guy’s watch for himself. He soon joins the gang, and they progress to bigger crimes.

The bulk of the film takes place, however, from when De Niro’s Noodles gets out of prison in 1930, following Bugsy’s murder, and lasts until the end of Prohibition in 1933. Max, now played by Woods, has become a successful bootlegger with a mortuary business on the side. With William Forsythe playing the grown-up Cockeye and James Hayden as Patsy, the mobsters go from bootlegging through contract killing, and ultimately to backing the biggest trucking union in the country as enforcers. They enjoy most of their downtime in their childhood friend Fat Moe’s (Larry Rapp) speakeasy. Noodles is in love with Fat Moe’s sister, Deborah, who is on her way to becoming a Hollywood star. The gang’s rise ends with the liquor delivery massacre.

The final part of the film comes in 1968. After 35 years in hiding, Noodles is uncovered and paid to do a private contract for the U.S. Secretary of Commerce Christopher Bailey… Max by a different name who 35 years on has been able to feign respectability and make Deborah his mistress. An entire life has become a façade.

Recreating a Seedier Side of New York’s Immigrant Past

While The Godfather is an adaptation of Mario Puzo’s fictional bestseller, Once Upon a Time in America is based on the autobiographical crime novel, The Hoods. It was written by Herschel “Noodles” Goldberg, under the pen name of Harry Grey while he was serving time in Sing-Sing Prison.

Coppola’s vision in The Godfather is aesthetically comparable to Leone’s projection. From the opium pipes at the Chinese puppet theater to the take-out Lo Mein during execution planning, the multicultural world of old New York crowds the frames and the players in both films. Most of Once Upon a Time in America was shot at Rome’s Cinecittà Studios. The 1918 Jewish neighborhood in Manhattan was a street in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, which was made to look exactly as it had 60 years earlier.

Leone skillfully, yet playfully, captures the poverty of immigrant life in New York. The first crime we see the four-member gang commit could have been done by the Dead End kids. They torch a newspaper stand because the owner doesn’t kick up protection money to the local mug. And like the Dead End kids, they needle their mark, and joke with each other. At the end of the crime, Cockey is playing the pan pipe, and the very young Dominic is dancing. They are proud of their work and enjoy it. It’s fun to break things for money. And even better when they get a choice between taking payment in cash or rolling it over into the sure bet of rolling a drunk.

Violence without the Cannoli

Gangster films, like Howard Hawks’ Scarface and William A. Wellman’s The Public Enemy, were always at the forefront of the backlash to the Motion Picture Production Code. Which might be why gangster pictures were one of the first genres to benefit from the censors’ fall. A direct line can be drawn from the machine gun death which ends Bonnie and Clyde (1967) to the toll-booth execution of Sonny Corleone (James Caan) in The Godfather. Another from when Moe Greene (Alex Rocco) gets one through the glasses and Joe Monaldi gets it in the eye in Once Upon a Time in America.

The Godfather has some brutal scenes. We get a litany of dead Barzinis and Tattaglias, horse heads and spilled oranges. Once Upon a Time in America ups the ante though. The shootings and stabbings are neat jobs compared with the beatings, which allow far more artistic renderings of gore, and pass extreme scrutiny. The one time the effects team balks at a payoff is when it’s not as gruesome as the setup.

“Inflammatory words from a union boss,” corporate thug Chicken Joe asks as he is about to light Jimmy “Clean Hands” Conway O’Donnell on fire. The mobster has such a nice smile, and the union delegate, played by Treat Williams, looks so pathetic while dripping gasoline that it feels like it might even be a mercy killing. It is a wonderful set piece, perfectly executed and timed. When Max and Noodles, and the gang defuse the situation, rather than ignite it, it is a lesson in the dangerous balance of suspense.

Like many specific scenes in Once Upon a Time in America, Conway’s incendiary introduction would’ve worked in any era. This is the turning point for the gang. The end of Prohibition is coming and all those trucks they’re using to haul liquor can be repurposed for a more lucrative future.

“You Dancing?”

Music is paramount in both Leone’s and Coppola’s films. The Godfather is much like an opera, the third installment even closes the curtain at one. Once Upon a Time in America is a frontier film. The score was composed by Ennio Morricone, who wrote the music behind Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, For A Few Dollars More, and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.

The film opens and closes with Kate Smith’s version of “God Bless America.” Though the scene occurs during the 1968 timeframe, the song comes out of the radio of a car seemingly from another point in time.

Morricone’s accompaniment to Once Upon a Time in America is as representational as Nino Rota’s soundtrack in The Godfather. Characters, settings, situations, and relationships all have themes, which become as recognizable as the Prohibition-era songs which flavor the period piece’s ambience. Fat Moe conducts the speakeasy orchestra through José María Lacalle García’s “Amapola” while grinning dreamily to Deborah who is chatting with Noodles. He’s a romantic.

Read more

Movies

Taxi Driver: A Look at NYC’s Inglorious Past

By Tony Sokol

Movies

The King of Comedy: What’s the Real Punchline of the Martin Scorsese Classic?

By Tony Sokol

The music becomes part of the action in Once Upon a Time in America. Individual couples cut their own rugs, doing the Charleston between tables as waiters and cigarette girls glide by. Cockeye, who has been playing the pan pipe since the beginning of the film, wants to sit in with the band.

Forsythe almost steals Once Upon a Time in America. He cries what look like real tears at the mock funeral for Prohibition and drinks formula from a baby bottle during the maternity ward scene. The blackmail scheme, which involves swapping infants, plays like an outtake from a Three Stooges movie, something Coppola would never dare for The Godfather. The ruse is choreographed to the tune of Gioachino Rossini’s “The Thieving Magpie,” which elicits the youthful thuggery celebrated in Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange.

Devils with Clean Faces

One ironic difference between the two films is whimsy. The Godfather, which glorifies crime as corporate misadventure, is a serious movie with no time for funny business. Once Upon a Time in America, which is an indictment of criminal life, has moments of innocence as syrupy as in any family film (of the non-crime variety) and can be completely kosher. It’s sweeter than the cannoli Clemenza (Richard Castellano) took from the car, or the cake Nazorine (Vito Scotti) made for the wedding of Don Vito’s daughter.

The scene where young Patsy brings a Charlotte Russe to Peggy in exchange for sex is a masterwork of emotive storytelling. He chooses a treat over sex. On one level, yes, this is a socioeconomic reality. That pastry was expensive and something he could never afford to get for himself. But as Patsy sneaks each tiny bit of the cream from the packaging, he is also just a child, a kid who wants some cake. He learns he can’t have it and eat it. It is so plainly laid out, and so beautifully rendered.

The Corleone family never gets those moments, not even in the flashbacks to Sicily or as children on the stoop listening to street singers play guitars. We know little of Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) or Sonny as youngsters, much less teenagers, and are robbed of their happier moments of bonding. We know they are close, they are family. But Michael has his own brother killed while Noodles balks at the very idea. Twice, as it turns out.

Read more

Movies

The Godfather Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone Proves a Little Less is Infinitely More

By Tony Sokol

Movies

Mob Antipasta: Best Gangster Movie Food Scenes

By Tony Sokol

“Today they ask us to get rid of Joe. Tomorrow they ask me to get rid of you. Is that okay with you? Cos it’s not okay with me,” Noodles tells Max after the gang delivers on a particularly costly contract, double-crossing their partners in a major diamond heist. They are not blood family, but from the moment Max calls Noodles his “uncle” to fool a beat cop, they are all related.

Noodles then does what young men in coming-of-age movies have done since Cooley High: Something really stupid. An indulgence the Corleones could never enjoy. He speeds the car into the bay. The guys can’t believe it. It adds to his legend. The scene could have been in Diner, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, or even Thelma & Louise. It is hard to dislike the gangsters in these moments. We know them too well, even as they do such horrible things.

How Women are Really Treated by an Underworld

The Godfather is told from the vantage point of one of the heads of the five established crime families; organized crime is as insular as the Corleone mall on Long Beach. That motion picture reinvigorated the “gangster film,” long considered a ghetto genre, but its perspective is insulated. By contrast, no matter how far they climb, Leone’s characters never really get off the block. They are street savages, even in tuxedos. Once Upon a Time in America whacked the gangster film, and tossed its living corpse into the compactor of a passing garbage truck.

The Godfather doesn’t judge its gangsters. The Corleones are family men who keep to a code of ethics and omerta. They dip their beaks in “harmless” vices like gambling, liquor, and prostitution. While there are scenes of extreme domestic violence, and a general dismissal of women, the film stops short of challenging the image of honorable men who do dishonorable things. Leone offers no such restraint. His history lesson is unabridged.

Long before Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman stripped gangster lore to a tale of toxic masculinity, Once Upon a Time in America robbed it of all glamor. There is a very nonchalant attitude toward violence and other demeaning acts against women in Leone’s film, from the very opening scene where a thug fondles a woman’s breast with his gun in order to humiliate her civilian date.

This is deliberate. The director, best known for Spaghetti Westerns, wants to obliterate any goodwill the gangsters have accumulated through their magnetic antiheroism. One scene between Max and his girlfriend Carol (Tuesday Weld) is so hard to sit through, even the other members of the gang squirm in their chairs.

Noodles sexually assaults two women over the course of the film. While there is some motivational ambiguity in the scene during the jewel heist attack, the rape of Deborah is devastatingly direct. It kills any vestige of romance the gangster archetype has in film. The camera does not look away, and the scene lingers with terrifying ferocity and traumatic intimacy. There is a visible victim, and Noodles’ wealth and pretensions of honor are worthless.

The Ultimate Gangster Epic

Once Upon a Time in America brings one other element to the genre which The Godfather avoids, a lingering mystery. Coppola delivers short riddles, like the fate of Luca Brasi, which are revealed as the story warrants. But the 35-year gap between the slaughter of Noodles’ crew and the introduction of Secretary Bailey is almost unfathomable. How did Max go from long-dead to a man with legitimate power?

What happens to Noodles in those years is fairly easy to guess, without any specifics. He got by. The gang’s shared secret bankroll was empty when he tried to retrieve it as the last surviving member. He put his gun away and eked out a quiet life. But even as the details spill out on the true fate of Max, it is unexpectedly surprising, as much for the audience as Noodles.

“I took away your whole life from you,” Max/Bailey says. “I’ve been living in your place. I took everything. I took your money. I took your girl. All I left for you was 35 years of grief over having killed me. Now why don’t you shoot?” This final betrayal, and Noodles’ inert revenge, take Once Upon a Time In America into almost unexplored cinematic depths.

Max has gone as low as he could go. The joke is on Noodles, everyone’s in on it, including “Clean Hands,” who is tied in to “the Bailey scandal.” The cops are in on it, and so is the mob. Max admits even the liquor dropoff was a syndicate set-up. He’d planned this all along. Just like Michael Corleone had a long term strategy to make his family legitimate.

This is an ambitious story. Beyond genre, this bends American celluloid into European cinema. By sheer virtue of being outside of Hollywood, Leone transcends traditional boundaries. He has a far more limitless pallet to draw from. He can aim a camera at De Niro’s spoon in a coffee cup for three minutes and never lose the audience’s rapt attention. Leone can pull the rug out from everything with a last minute reveal. Coppola bent American filmmaking for The Godfather, but stayed within proscribed parameters. He never gets as sweet as a Charlotte Russe nor as repulsive as the back seat of a limo.

Once Upon a Time in America ripped the genre’s insides out and displayed them with unflinching veracity and theatrical beauty. It is a perfect film, gorgeously shot, masterfully timed, and slightly ajar.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

The post Once Upon a Time in America Is Every Bit as Great a Gangster Movie as The Godfather appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/3yRxHIy

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy #StrikeStrikeStrikeDay!

Time for some girl power up in this business.

So, here’s how it goes:

Smalls likes to make up stories about the other people she sees on the street as she’s selling her papes.

A man in a nice suit? An architect, but he wishes he were in the circus. Those two ladies who head toward the church almost every day? Considering becoming nuns so the highwayman they robbed as they traveled to New York can’t find them.

Melodramatic? Yes. But does it keep the day from dragging on? Also yes.

If the other newsies ask, she’ll tell them one of the stories she made up, but never the one about the pretty girl she sees walking home from school with her brothers.

That girl’s story is hers and hers alone, though it isn’t actually very long.

One day, she stops as she passes me, Smalls thinks. She waves for her brothers to go ahead before walking over, smiling that bright smile. “I’ve been meaning to introduce myself,” she says. “I’m-”

And that’s as far as it ever gets, because Smalls can’t figure out what name would be beautiful enough to fit her.

Smalls has resigned herself to her fantasies by the time the girl’s brothers appear at the circulation gate, almost making her trip over Albert’s stick.

It turns out Les and Davey need jobs to help support their family after their father got in an accident, and Sarah (Sarah!) is also starting work at a factory to do her part.

Smalls can only hope that maybe one day Sarah will end up walking past Newsies Square with her brothers before she continues on to work.

Just as Smalls is processing this change, a second beautiful girl enters her orbit.

What in God’s name did Smalls do to deserve this?

Katherine is a lightning strike, and Smalls is ready to burn.

Once Katherine puts Jack in his place (eternally endearing her to Smalls, much as she loves that fearless cowboy), she makes a point of walking through Jacobi’s and introducing herself to each and every newsie there.

“Oh! Finally, another girl,” Katherine says as she approaches Smalls. “Thank God. You boys all seem wonderful so far - yes, even you, Jack - but you’re also a little exhausting.”

“You’re telling me,” Smalls replies, amazed she can make words when Katherine is looking her right in the eye. “You don’t have to go back to the lodging house with them. Just once, I’d like to pull my hair up in the morning without dodging the elbows of six boys all trying to shave their invisible beards at the same sink.”

There’s a good-natured uproar at her comment, but Smalls only notices Katherine’s delighted laughter.

“You poor thing,” she croons in between giggles. “Come here.”

Katherine hugs her, and Smalls forgets how to breathe.

“Good luck tomorrow,” Katherine says as she lets go and moves on the next newsie, taking Smalls’ breath away for an entirely different reason.

The next morning, Smalls squares her shoulders as she enters the circulation gate.

She’s determined to do her part as a hardworking newsie and make Pulitzer treat them the way they deserve.

She’s also determined to not make a fool out of herself in front of Katherine - maybe even impress her a little bit.

Besides, all Wiesel has to back him up is the Delanceys. They can take down the Delanceys if they all work together!

Smalls manages to kick Oscar right in the knee as he’s chasing Crutchie during the scuffle, and she feels invincible.

Hearing Katherine cheer for her from her position safely away from the fray doesn’t hurt, either.

And then the strikebreakers appear.

Smalls is terrified, but she isn’t going to back down from this fight. She can’t afford to pay an extra dime for the same amount of papers, and it isn’t right that Pulitzer and the other newspaper owners can make that change without consulting their employees!

She’s also not stupid, though. She knows she can’t take down a grown man by force alone.

So she darts in and out of confrontations, tripping the strikebreakers or whacking their knees and elbows with a board that got ripped off the delivery wagon.

It works pretty well, until it doesn’t.

Out of the corner of her eye, Smalls notices a cop running right at Katherine, who’s trying to pull an injured Jojo out of the way.

Smalls reacts without thinking, throwing herself in front of the cop just as he’s preparing to hit Katherine in the arm to get her to let go.

He can’t stop himself, nor does he want to. Smalls can see it in his eyes in the split second before she gets hit.

And then the world goes black.

Smalls wakes up in a small yet cozy apartment. Some of the other hurt newsies are curled up around her on a variety of makeshift beds, so she knows she must be somewhere safe, but that doesn’t stop the panic from rising as she sits up to inspect more.

“Shhh,” a kind, soft voice says from her right. “It’s okay.”

Smalls turns toward the voice and nearly falls over.

“I’m Sarah, David and Les’s sister,” she says, as if Smalls doesn’t know. “You’re in our apartment. David convinced Katherine and the other newsies who escaped to come here for help.”

“Escaped?” Smalls croaks, trying not to move her aching right cheek too much.

Sarah’s eyes are concerned as she says, “Warden Snyder arrived on the scene after you were hit. He got Crutchie before anyone could help him get away.”

Smalls’ stomach drops. The Refuge is no place for anyone to go, but especially not for someone as goodhearted as Crutchie.

“What about Jack?” she asks.

“We can’t find Jack,” Sarah replies. “He’s not at the Refuge - Race already confirmed that - but he’s also not at the lodging house or the rooftop.”

Before Smalls can even begin to figure out what to say at that, another voice interjects.

“You’re awake!” Katherine whisper-cries, flinging herself into the chair next to Sarah and taking her hand. “I was so worried about you. That policeman hit you hard enough that I saw stars.”

“But it gave you time to get Jojo out.”

“Yes, he’s here too, thankfully,” Katherine says.

“No thanks to you,” Sarah teases. “Once you saw that Smalls was unconscious, he says you practically threw him to the wolves.”

Katherine makes an indignant noise as Smalls stifles a laugh.

“I did not!” Katherine says. “Finch was right there to help him up and get him farther away. Smalls had no one, and Snyder was about to come back for seconds!”

“So you hurl Jojo at Finch before scooping up Smalls like a hero from a novel?” Sarah says through a giggle.

Smalls’ heart starts pounding at the thought.

Katherine was holding me?

“She sure was,” Sarah says, and Smalls flushes as she realizes she said that thought aloud. “David said she refused to put you down until everyone reached the outside of our apartment and Katherine realized she couldn’t get you up the stairs in her skirts.”

Katherine looks mortified, but she manages to joke, “Remind me to become a dress reformer before our next strike.”

Smalls cannot even begin to picture Katherine in bloomers if she wants to be able to speak coherently.

“Thank you,” she whispers instead. “No one does well at the Refuge, but there are stories about how the girls are treated there - it’s not like how they mistreat the boys.”

Katherine and Sarah don’t need her to elaborate.

“We are not going to abandon you,” Katherine declares, shifting to sit on the edge of Smalls’ bed and take her hand. “Not you, and not anyone involved in the strike. We have to stick together.”

“That’s right,” Sarah says. She puts her right hand on Smalls’ shoulder, and since her left is still in Katherine’s other hand, the girls form a loose triangle. “But those boys are all over each other in a way they don’t think to be with us. Let’s make sure we’ve especially got each other’s backs.”

“Deal,” Smalls says, and the other girls are gracious enough to not mention the tear streaking down her face.

After that, the world shifts ever so slightly for Smalls.

Well, there are big changes, too: there are plans for a city-wide newsie rally, and then when they’re all gathered at the theater, Jack stuns them all by turning scab.

But more importantly, Smalls develops deeper relationships with Katherine and Sarah.

At first, it’s little things.

Katherine and Smalls meeting eyes from opposite sides of Jacobi’s as Romeo practices yet another awful pick-up line.

Sarah deliberately walking by Smalls’ selling spot on her way to work every morning to share a smile and a quick hello.

Then bigger events.

Sarah inviting Smalls over for Shabbat when she learns that Smalls is also Jewish but unable to practice as faithfully at the lodging house.

Katherine joining Smalls every day at lunch time in the park between The Sun’s offices and the corner where Smalls sells her papes, rain or shine.

Finally, everything comes to a head as Jack leaves the stage after scabbing.

Davey’s chasing him, so Sarah and Katherine and Smalls are all following when Pulitzer appears from the fire door with a wad of bills.

Throwing the bills to Jack, he says, “Oh, and my daughter will be coming home with me now.”

Jack, Davey, Sarah, and Smalls all freeze, confused, but Katherine jerks back before turning beet red.

“Yes, Katherine is my daughter,” Pulitzer continues, clearly enjoying the havoc he’s causing. “I refused to let her sully herself by working for a living at one of my newspapers, but she defied me and got a nom de plume instead. An unfortunate lapse in judgment. Come along, sweetheart.”

Katherine looks around imploringly at the others before hurrying off after her father. Smalls moves to follow, but Sarah stops her.

“No, don’t give him another reason to come after us.”

Instead, Sarah, Smalls, and the boys go back to the Jacobs’ apartment. Jack and Davey head up to the roof, where Smalls has no doubt they will have a “discussion” (read: argument), so she and Sarah take the fire escape.

They have a half-hearted talk about the rally, but Smalls can tell they’re both just trying to avoid thinking about-

“Katherine!”

“Hello. Am I - am I still welcome here?” she asks, voice cracking.

“I can’t speak for Sarah, but you’re always welcome where I am,” Smalls says, scurrying down the steps to give Katherine a hug. “I thought about it as we walked back here, and I just don’t believe you had anything to do with your father’s position in the strike. You’ve been with us from the start, Katherine. You carried me away from the fight when I got knocked out. Who cares what name you were using? Your actions prove who you really are.”

“I couldn’t agree more,” Sarah says, joining them on the pavement and wrapping her arms around each of their shoulders. “Hell, after meeting your father, I can understand why you would use another name. He’s the worst!”

Katherine laughed, though there were tears spilling down her cheeks.

“The absolute worst!” she agrees.

Smalls wants to lean in and kiss those tears away, then kiss Sarah for helping to break the tension, but then-

“You’re back!” Davey cries, spilling out of the front door with Jack on his heels. “And Jack’s not actually a scab!”

“Wow, banner day,” Smalls mutters, making Sarah giggle.

“Good, because I have an idea,” Katherine says. “Jack, that speech you gave before the strike? That wasn’t just about the newsies. Every child in this city suffers under terrible bosses and bad working conditions. If we got every kid in the city to join us on strike-”

“They would have to listen to us!” Jack finishes. “Plumber - can I still call you Plumber? - you’re a genius.”

“How do we get the word out, though?” Sarah asks. “It’s a wonderful idea, Katherine, but it will only work if people know about it.”

“My father’s declared a blackout on strike news, as we well know,” Katherine says. “But there’s got to be a press somewhere he doesn’t control.”

There’s silence for a moment until Jack snorts.

“Oh, no.”

“What?” Smalls asks.

“I know of a press Joe would never dream we’d use. Follow me, everyone.”

Hours later, Smalls is exhausted. After Jack and Katherine got them into the cellar at Pulitzer’s office, she ran from one side of the city to the other, alerting newsies about the new plan and sending them off to collect their papes.

Every muscle in her legs aches, but she’s never felt more exhilarated.

“We’re doing it!” Sarah cries. She, Smalls, and Katherine are all tucked in a corner of the cellar, hand in hand, taking a quick break before Katherine heads off to personally deliver their paper to the governor.

“This has to work,” Smalls says, looking from Sarah to Katherine. “I can feel it.”

“Keep your fingers crossed anyway?” Katherine asks, lifting her free hand to show the gesture.

It’s so unbearably cute that Smalls just can’t resist anymore.

“Anything for you.”

And with that, she leans in and kisses Katherine, keeping a good grip on Sarah’s hand as well.

“Knowing us, we’re going to need it,” Sarah says before taking Smalls’ place to smooch Katherine herself.

Katherine kind of looks like she’s going to fall over, but she’s got a grin that could replace the sun.

“Now get out of here, you’ve got an important man to see!” Smalls says, knowing her own smile is as wide as Katherine’s.

She waves her newly freed hand before turning to Sarah.

“As for you-”

“Get over here already!” Sarah interrupts, pulling Smalls in so they can finally kiss.

Smalls has never been happier to follow an order in her whole life.

Before she knows it, they’re gathered with the rest of the newsies outside Pulitzer’s office, waiting for Jack, Davey, Spot, and Katherine to come back out with the results.

When they do, the boys stay on the balcony with Pulitzer as Jack gives them the good news, but Katherine joins Sarah and Smalls in the throng.

Smalls is screaming, overjoyed at the results, and Sarah is bouncing up and down alongside her.

Katherine flings her arms around them both, and for a second the world is just the three of them in a warm embrace.

“So what happens now?” Smalls asks eventually.

“Well, right now, we’re going to go tell my parents the good news, and they will inevitably make you stay for dinner,” Sarah says, glowing.

“And then we do our best to stay forever,” Katherine finishes.

“Pick an easier fight, why don’t you, Katherine?” Sarah teases.

“After all this, don’t we deserve easy?” Smalls points out.

“We absolutely do.”

#strikestrikestrikeday#newsies#jen does words#katherine plumber/sarah jacobs/smalls#is there even a portmanteau for this

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Best Live Action Short Film Nominees for the 92nd Academy Awards (2020, listed in order of appearance in the shorts package)

Since 2013 on this blog, I have been reviewing the Oscar-nominated short films for the respective Academy Awards ceremony. Normally, the Oscars are held on the last Sunday in February and we, the moviegoing public, are given more than a few weeks to seek out the nominated films. Not this year, as the ceremony was held at the earliest date ever (it reverts back to its usual starting date, the last Sunday in February, for the next two years starting in 2021).

There’s already been a winner in this category, but nevertheless here are the five nominated films for Best Live Action Short Film. Congratulations to Tunisia for two of the five entries, but all these shorts reflect the cinematic democracy that are the short film categories.

A Sister (2018, Belgium)

Also known by its original French title, Une soeur, A Sister is directed by Delphine Girard. It is the only piece among its fellow nominees that could be envisioned only as a short film. As such, its sixteen-minute runtime requires succinctness, the filmmaking as tightly wound as a clock. Late at night, a woman named Alie (Selma Alaoui) is sitting in the passenger seat asking the man (Guillaume Duhesme) for a cell phone so she can call her sister. We hear the first few seconds of this phone call. The screen cuts to black; next, we see a bustling room with numerous people gazing into computer screens, speaking to various people over headsets. We soon realize that Alie is dialing for an emergency call center. She is being kidnapped, and does not recognize the highway they are driving on. The operator (Veerle Baetens), confused by Alie’s coded language at first, eventually intuits what exactly is going on.

Alie and the operator exercise caution during these precarious minutes, as A Sister unravels in its teeth-grinding escalation of tension. Girard notes that the inspiration for A Sister came when she heard of a story of a young American woman calling 911, pretending that she was calling her sister – “it was the story of building a story of empathy and sorority that inspired [Girard].” Through meticulous research about protocols during emergency services calls that included interviews with said operators (who also made suggestions about draft screenplays), A Sister accomplishes a dramatic urgency that films with similar goals but last far longer never reach. The clever chronological edit in the film’s opening minutes contribute to that escalation; so too the decision to shoot from the backseat, obscuring Alie’s face to make the audience rely almost entirely on vocal delivery to understand her desperation and his paranoia (although the darkness of the surroundings can leave audiences confused in the opening minutes about who or what we are looking at). Not a second of A Sister is a wasted one.

My rating: 9/10

Brotherhood (2018, Tunisia/Canada/Qatar/Sweden)

Having made its rounds across the international film festival circuit, Meryam Joobeur’s Brotherhood is an international cross-stitch of a short film serving as an expression of Joobeur’s Tunisian roots. The film’s tragic outcome and dour tone throughout make is akin to Greek drama, where the ending feels predetermined and the characters – in what makes them essential – barely evolve. In a coastal, rural Tunisian town, a married couple and their two youngest sons make their living as sheep farmers. The landscape is rugged, their lives simple. One day, the eldest son – who has been missing for more than a year – returns home. With him is his teenage wife, wearing a full niqab, pregnant, and instantly attracting suspicion from the father. The eldest son and his wife met in Syria, where the former joined the so-called Islamic State (referred to by everyone else in the family by its acronym, Daesh – considered an insult to those affiliated with ISIS) out of desperation to flee his implicitly abusive father.

Brotherhood is indulgent in its languor, sometimes hanging onto certain shots well beyond necessary. Long cuts are welcome in cinema to allow the audience to meditate about what has just occurred; their emotional and philosophical implementation in Brotherhood is inconsistent. A constant use of close-ups and the film’s 4:3 screen aspect ratio reflect each parents’ stubbornness that their opinions about their situation is correct, that the eldest son’s belief that he is morally unblemished (he professes not to have killed, nor having been an accessory to killing another). The near-complete use of natural lighting - the overcast skies, the orange hues of older electric lights – lends the film authenticity. Joobeur, a Montreal-based filmmaker, has stated that she made Brotherhood to reclaim the humanity that the Muslim world has lost to the West since 9/11. From the red hair of the brothers, the ambiguity of the eldest son’s time in Syria, to the dramatic irony that closes the film, Brotherhood always challenges those views that Joobeur wishes to reclaim.

My rating: 7.5/10

The Neighbors’ Window (2019)

Marshall Curry is principally a documentary feature producer (2005′s Street Fight, 2017′s A Night in the Garden). The Neighbors’ Window, which he directed, is only his third narrative short film and, unfortunately, the final product is indicative of that – he has directed a handful of documentary features and shorts, but the techniques and lessons learned there are not always congruent to narrative short films. Here, mother Alli (Maria Dizzia) and father Jacob (Greg Keller) are New Yorkers with young children (early grade school and preschool age) who have settled into what they both feel has become a monotonous lifestyle. One evening, they see through their apartment window that, across the street, a younger couple have just taken up residence. Without pulling down any blinds and in their erotic euphoria, the younger couple start unpackaging (and this has nothing to do with moving boxes). Like Jimmy Stewart in Rear Window (1954) but without the murder, Jacob and especially Alli will occasionally peer into their new neighbors’ apartment to voyeuristically observe.

The Neighbors’ Window has little to say beyond its assertion the grass is always greener on the other side – it pains me to have written such a cliché. Other than basic editing, this is a film devoid of any aesthetic experimentation or narrative interest. The film’s plot twist, inspired by a true story heard on the podcast Love + Radio, is not strengthened by the lackluster acting. The supposed emotional catharsis that should emerge in the film’s final moments is simplistic – redeemed neither by said acting or the film’s questionable screenplay. It is, at worst, tasteless. The premise of The Neighbors’ Window is indeed worthy of cinematic treatment – perhaps even as a feature – but Curry is not up to the task.

My rating: 6/10

Saria (2019)

It is a fine line between politically-tinged narrative/documentary filmmaking and agitprop. Bryan Buckley’s Saria, a dramatization of the events that led to the deaths of 41 girls between fourteen and seventeen years old in a 2017 Guatemala orphanage fire, almost becomes exactly that. Saria (Estefanía Tellez) and her elder sister Ximena (Gabriela Ramírez) are orphans at the La Asunción Safe Home. It is a safe home only in name, as Saria, Ximena, and the many other girls housed in the orphanage are victims of staff abuse or human trafficking. Saria and Ximena dream of a life far from the girls’ dormitory at the orphanage, and there have been mumblings about a joint plan between the boys and girls at the orphanage to cause a diversion in order to begin an escape, en masse, on foot, to the United States. Given that Saria is based on a tragedy, there is only one resolution possible.

However, despite being confined to that horrific ending, the film endows its two central characters with distinct personalities and aspiration to the extent that it can. In its twenty-two minutes, Saria not only depicts the squalor and prison-like conditions of the safe home, but the desperate humanity of its subjects – as if taking a page from Italian neorealism, this film has orphaned children playing orphaned children, but the direction and writing behind their performances can be frustrating. Saria is somewhat hampered by its editing, as the emotional impact of the escape scene to the film’s final minutes feel rushed. The film’s pre-closing credits reveal – that Saria is indeed based on actual events and no one has ever been held accountable for the deaths of the forty-one girls – is harmed because of the film’s prosaic editing.

My rating: 8/10

Nefta Football Club (2018, Tunisia/France/Algeria)

On its face, Yves Piat’s Nefta Football Club – another transnational production set in Tunisia – has all the hallmarks of a film that spirals into a disastrous conclusion. Yet what instead transpires is a witty comedy that mostly adopts the point of view of its two child protagonists. Near the Tunisian-Algerian border, Mohamed (Eltayef Dhaoui) and Abdallah (Mohamed Ali Ayari) are soccer-obsessed brothers bickering over who is the best player in the world: Lionel Messi or Riyad Mahrez (personally, I have never heard Mahrez in that conversation, but noting that he is Algerian and almost certainly the greatest Middle Eastern or North African player in history, this sounds like a realistic conversation). While heading home, the boys encounter a donkey wearing headphones and carrying bags of white powder. They take the “laundry detergent” home for their mother, with the intention to sell the rest to their neighbors. Somewhere in the desert, two men are waiting for their delivery donkey to arrive.

Don’t worry, those two men will never have a clue whatever became of their delivery. Piat came up with the idea for Nefta Football Club while recalling childhood memories of him and his friend sneaking out of their house at night, finding white powders that they believed to be illicit materials, and dumping all of this into a body of water. Nefta Football Club showcases a loving, hilarious relationship between elder and younger brother, as well as the perspective divides of the eldest brother’s teenage calculation and the younger brother’s innocence. Their life station is never fully explored, nor is it ignored by Piat. Piat’s screenplay – based on believable misunderstandings that are based on the characters’ personalities – is well-executed, as evidenced by its fantastic final punchline.

My rating: 8/10

^ Based on my personal imdb ratings. Half-points are always rounded down.

From previous years: 85th Academy Awards (2013), 87th (2015), 88th (2016), 89th (2017), 90th (2018), and 91st (2019).

#A Sister#Brotherhood#The Neighbors' Window#Saria#Nefta Football Club#Delphine Girard#Meryam Joobeur#Marshall Curry#Bryan Buckley#Yves Piat#92nd Academy Awards#Oscars#My Movie Odyssey

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

LUCY GETS HER MAN

S1;E21 ~ February 24, 1969

Directed by Jack Donohue ~ Written by Fred S. Fox and Seaman Jacobs

Synopsis

Harry's old Army buddy is working in Counter-Intelligence and needs a stenographer to help get the goods on a suspected spy (Victor Buono). Naturally, Lucy gets the assignment.

Regular Cast

Lucille Ball (Lucy Carter), Gale Gordon (Harrison Otis Carter), Lucie Arnaz (Kim Carter), Desi Arnaz Jr. (Craig Carter)

Guest Cast

Victor Buono (Arthur Vermillion) was a character actor whose screen career began in 1959. He was nominated for a 1963 Oscar for his portrayal of Edwin Flagg in Whatever Happened To Baby Jane, which he quickly followed up with Hush, Hush Sweet Charlotte, both starring Bette Davis. He is perhaps best remembered for playing arch-villain King Tut on “Batman” (inset). Buono died in 1982 at the age of 43.

Buono uses a thick middle-European accent as Vermillion. According to the dictionary, ‘vermillion’ (or ‘vermilion’), describes a deep, brilliant shade of red. ‘Red’ is slang for a communist, based on the color of the communist flag, which ties into the spy theme of the episode.

Mary Wickes (Isabel) was one of Lucille Ball’s closest friends and at one time, a neighbor. She made a memorable appearances on “I Love Lucy” as ballet mistress Madame Lamond in “The Ballet” (ILL S1;E19). In her initial “Lucy Show” appearances her characters name was Frances, but she then made four more as a variety of characters for a total of 8 episodes. This is the first of her 9 appearances on “Here’s Lucy.” She also played Isabel in “Lucy Goes on Strike” (S1;E16). Their final collaboration on screen was “Lucy Calls the President” in 1977.

Wickes only has 40 seconds of screen time at the very start of the episode. Before Mary Jane Croft joined the show, the character of Isabel was intended to be a secretary friend of Lucy Carter’s who works in her building. Wickes only played the character twice before moving into different characters for the rest of the series.

Robert Carson (Buzzy Brock) was a busy Canadian-born character actor who appeared on six episodes of “The Lucy Show.” This is the second of his five appearances on “Here’s Lucy.”

Buzzy was an Army Colonel at the Pentagon during World War II. He got a Purple Heart when his desk collapsed! He is currently working with 'Counter-Intelligence'.

Chicago Tribune, February 24, 1969

This is the third spy story on “Here’s Lucy” in just five months, preceded by “Lucy's Impossible Mission” (S1;6) and “Lucy and the Great Airport Chase” (S1;E18). Spy series' such as “Get Smart” and “Mission: Impossible” were tremendously popular at the time. Craig mentions a show called “Spy Mission” and Kim talks about “Counter Agent,” both made-up TV spy programs.

Lucille Ball and Victor Buono were both featured in “Like Hep!”, a Dinah Shore special that aired a few months after this episode. In it, Ball did a variety of sketches, including one set in a speakeasy with Buono as a mob boss.

Upon arriving at work, Lucy off-handedly says “another day behind the iron curtain.” The Iron Curtain was the name for the imaginary boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. The use of the term contributes to the spy nature of the story, but seems a bit precipitous considering the plot has yet to be revealed!

Isabel calls Harry Jack the Ripper, comparing him to the famous London serial killer. There was also a character named Jack D. Ripper in the 1964 iron curtain comedy Dr. Strangelove. Could this be another vague and precipitous reference to the episode’s theme?

After Isabel and Harry continually bump into one another going out the door (doing a sort of ‘after you’ dance) Harry calls her St. Vitus. Saint Vitus (290-303 AD) was a child saint from Sicily. In the late Middle Ages, people celebrated the feast of Vitus by dancing before his statue. The name "Saint Vitus Dance" was given to neurological disorders like epilepsy. It also led to Vitus being considered the patron saint of dancers.

We learn that Harry was an Army major during World War II and worked at the Pentagon.

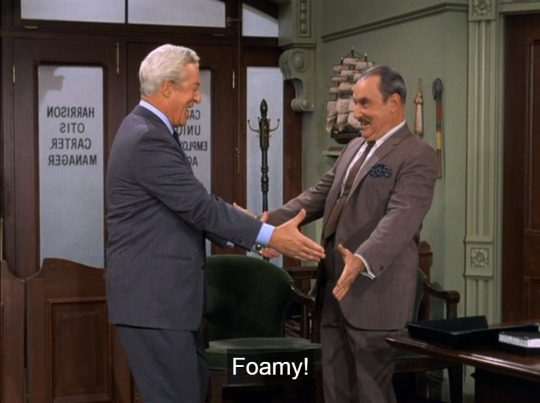

Buzzy calls Harry 'Foamy' because he wore out twelve foam rubber cushions on his swivel chair. Clearly Buzzy and 'Foamy' (aka Harry) were desk jockeys during the war. The script doesn't specify, however, why Buzzy is named Buzzy.

When Kim comes home from school, she asks her mother if Jerry called. Presumably, Jerry is her boyfriend. Jerry was also the name of Lucy Carmichael's son on “The Lucy Show.” She uses her childrens’ questions as a memory test for her upcoming spy assignment.

Kim says her birthday is the 17th of next month. In real life, Lucie Arnaz's birthday is the 17th of July.

The song Kim and Craig play for Uncle Harry, to show him what life with teenagers in the house might be like, is a jazzy version of “I Know A Place” by Tony Hatch. The song was recorded in 1965 by Petula Clark. It is here performed without lyrics with Kim dancing and Craig playing the drums. Lucy danced to the song in “Mod, Mod Lucy” (S1;E1). Clark will do a guest appearance on the series in season 5, although she will not sing “I Know A Place.”

When Lucille Ball enters Vermillion's hotel suite at the (fictional) Crescent Palms Hotel wearing a black wig, she gets a round of applause from the studio audience.

If the horse statue in Vermillion’s hotel room looks familiar, it is likely the same horse used later that year on the set of “The Brady Bunch” (1969-74). Both shows were filmed at Paramount Studios. Similar horses also turned up on “Bewitched” (1964-72) and in the film Bell, Book and Candle (1958) starring Ernie Kovacs. This iteration of the horse statue has its saddle and reigns painted black, but they are otherwise identical. Equine statuary was quite common in mid-century decorating.

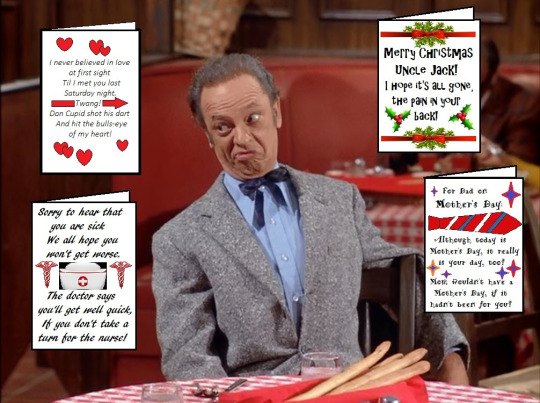

Vermillion, under the guise of a greeting card writer, dictates correspondence to

Gregory Schmidt, General Delivery, St. Louis, Misery

and another to

Igor Shaffsky, Hotel Scimitar, Istanbul

He eats his notes. Is he really a spy or just really hungry?

When Vermillion looks around the room to see that they he and Lucy are alone, the soundtrack plays “Mission: Impossible” style music. The TV score by Lalo Schifrin was extensively used in “Lucy's Impossible Mission” (S1;E6).

Victor Buono is best known for his role in the Bette Davis / Joan Crawford 1962 horror film What Ever Happened to Baby Jane, a movie that was mentioned on “No More Double Dates” (TLS S1;E21). Lucy Carmichael rejected the film for date night as “too scary”. Coincidentally, both shows were the 21st aired episodes aired in their first seasons!

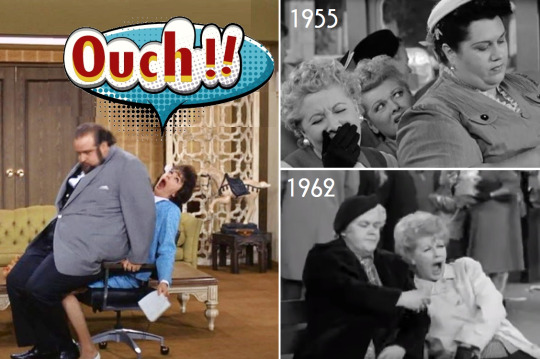

This is not the first time Lucy has mined humor from being sat on by a larger actor. She was underneath a tubby tourist (Audrey Bentz) in “The Tour” (ILL S4;E30) and a girthy granny (Reta Shaw) in “Lucy Misplaces $2,000″ (TLS S1;E4).

Lucy Ricardo also “wore a wire” when trying to record a confession by who she thought was a Texas oil swindler in “Oil Wells” (ILL S3;E18). Both times her urge to be wired for sound was misguided.

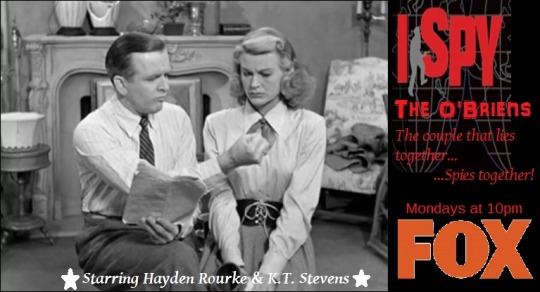

Thinking they were enemy agents, Lucy Ricardo also spied on the “New Neighbors” (ILL S1;E21). Like Vermillion, the O'Briens were not who Lucy first assumed they were but they sure talked a good game!

This is not the first, nor the last, time Gale Gordon will get into unconvincing drag without shaving off his mustache!

FAST FORWARD!

On August 16, 1971, Victor Buono and Lucille Ball were both guests on “The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson”. Kaye Ballard was the musical guest.

Vermillion is not the last character to be a writer of greeting card verses...

It would also be the occupation of Ben Fletcher (Don Knotts) when “Lucy Goes on Her Last Blind Date” (S5;E16).

Sitcom Logic Alert! Craig just happens to own a pocket-sized miniature tape recorder. Doesn’t every teenager in 1969?

Color Blind! Vermillion tells Harry (as the Bellboy) that he “never wears blue” yet he is clearly wearing a powder blue tie. Is he just trying to get rid of Harry through intimidation?

Product Dis-Placement! The brand name of Craig’s drum set is partly taped over. The top loop of the ‘R’ reveals that it is made by Rogers. Founded in 1849 in Farmingdale, NJ, by Joseph Rogers, the company went out of business in 2006.

Where the Floor Ends! In the lower right corner of the above screen shot, viewers get a glimpse of where the Carter’s wall-to-wall carpet ends and meets the cement stage floor!

“Lucy Gets Her Man” rates 3 Paper Hearts out of 5

A nearly five minute scene without Lucille Ball, when Kim and Craig convince their Uncle Harry to keep an eye on their mother, is a bit awkward and too long. Mary Wickes is given virtually nothing to do in this episode. Her lines could just as well have been spoken by an uncredited day player. Lucille Ball's scene with Victor Buono, however, is quite good and Gale Gordon in maid drag (with his trademark mustache) is well worth the wait. The surprise ending actually makes sense and is very funny, if a bit abrupt.

“Ja. Yust like mama!”

#Here's Lucy#Lucy Gets Her Man#Lucille Ball#Gale Gordon#Lucie Arnaz#Mary Wickes#Desi Arnaz Jr.#Victor Buono#drag#I Know A Place#spy#Robert Carson#Jack the Ripper#Saint Vitus#Iron Curtain#King Tut#What Ever Happened to Baby Jane#Lalo Schifrin#Mission Impossible#TV#1969#CBS

5 notes

·

View notes