#Ivan Cloulas

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

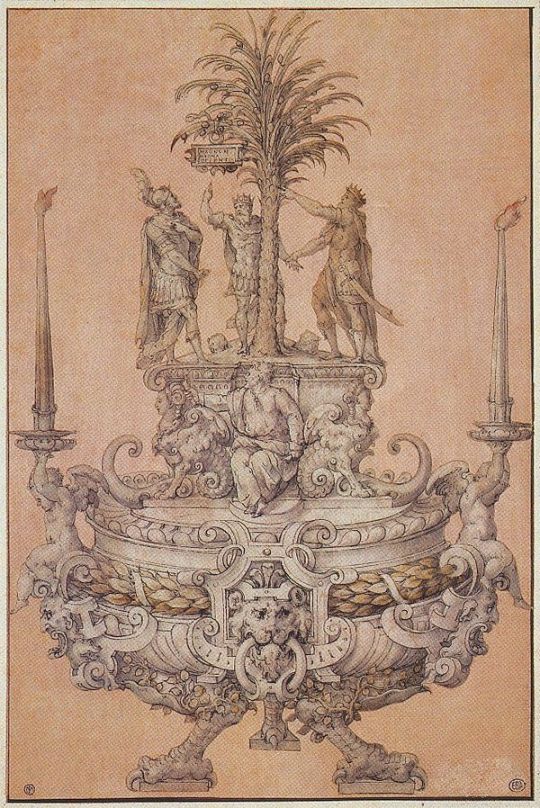

Jean Cousin the Elder, Vessel Presented by the City of Paris to Henry II of France on the occasion of his entry into Paris in 1549, 1549, pen and ink wash, India ink with watercolour on vellum, 30.2 × 20.1 cm, École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris

Source: Wikimedia Commons, Cloulas, Ivan/Bimbenet-Privat, Michelle: Treasures of the French Renaissance. Translated by John Goodman. New York 1998.

#art#design sketch#design sketches#design#kunsthandwerk#drawing#jean cousin the elder#mannerism#mannerist design#mannerist art#1540s#16th century#16th century art#16th century design#northern mannerism#16th century drawing#mannerist drawing

0 notes

Text

i finally finished reading cesare’s biography by ivan cloulas! oh boy... what a journey lol! unfortunately, it took me a long time because i started my studies back in 2019 (and now i had to interrupt them so... i started reading again) the book is not long but as i said, my masters was demanding me a lot and i was only able to focus on academic books/ articles in communication and nothing related to the borgia family and i was missing them like... a lot :’)

well, i will not write a detailed bible because 1) i really need to read more biographies to have more understanding and info to compare 2) this is my humble contribution (and a documentation of my own reading) and that's fine by me! i really have a lot to learn and i'm looking forward to it! i know that i have a long way about borgia books but unfortunately adult life hit me hard and i had to slow my steps.

i was fortunate enough to read this book when i was really thirsty for knowledge and beyond that (no joke) it helped me so much with my depression. the days are not being easy at the moment and being able to embark on the italian renaissance with cesare was great! obviously the book is focused on cesare's military actions (after rodrigo's rise) but i managed to have more information about rodrigo and lucrezia as well <3 and i’m ALWAYS here for lucrezia, always! however, said that i believe the feeling of disappointment will be a striking feature in this way of getting more involved with the borgia family!

unfortunately, cloulas is not very open to detailing information and i was often waiting for more information about the information (if that makes sense lol) like... how did he find out how charlotte d'albret felt or how rodrigo decided y instead of x? cloulas had the power of divination? it's frustrating... (i need sources) not to mention the excessive drama that is constant in most chapters. cloulas makes a point of adjectifying cesare's actions as if he (cloulas himself) had supreme power and that bothered me terribly! that narrative of 'only the prince of machiavelli' is so boring... come on! we know that cesare is more than that - he's fascinating enough to have biographies about him, right? i would LOVE to have more detailed information, footnotes, letters and explanations of the difference between opinion and fact! i like the way cloulas chose to write - it's an easy and enjoyable read - but it bothers me the need for drama most appreciated in fiction... perhaps the moral present in his personality has gone far beyond the historical narrative idk ??????

i don’t regret reading it and i really believe that each (well structured) information is valid! i would just like a bigger adjustment in how the biographers interested in writing about the borgia family decide to do their work... i appreciate the research (always) but it would be good to have the total clarity of their movements... i personally miss it! i found other biographers of other figures more "organized" in this aspect but as i said, i’m here to read and collect info and my own opinions and ofc change them as well ;-) more than that, i’m grateful to be able to read more about it!

#shit i say#and post#personal#books#cesare borgia#the borgia family#ivan cloulas#borgia stuff#mine#I FINISHED SOMETHING!#~~amen

15 notes

·

View notes

Link

"La grandezza di #LorenzoIlMagnifico fu tale da trasformare la Repubblica fiorentina in un regime assoluto che fu anche «opera d’arte», per diplomazia, senso politico e accortezza"

0 notes

Video

youtube

APOSTROPHES | 23 juillet 1982

Bernard PIVOT reçoit Umberto ECO pour son livre "Le nom de la rose" dont l'action se déroule dans une abbaye en Italie du nord à la fin du moyen âge. L'écrivain parle de l'intrigue de son roman et des personnages qui le composent. Présence et réactions des autres invités Ivan CLOULAS, Hector BIANCIOTTI et Max GALLO.

#bernard pivot#umberto eco#ivan cloulas#max gallo#hector bianciotti#Le nom de la rose#apostrophes#ina#culture#ina culture#en français

0 notes

Note

What is your personal Top Ten of Borgia nonfiction books, and why would you choose them?

Ohh, ok, I don’t think I have a top ten??? but let’s see how this goes! lol I'll separate it in two sections: non-fiction books about the Borgia family as a whole and non-fiction books about individual members of the family (tbh just Rodrigo and Cesare), I’ll focus on secondary sources, but let me know if you also meant/want primary sources :))

Non-Fiction Books about the Borgia Family:

The Borgias: The Hidden History, G.J Meyer

His book has some flaws, which I’ve talked about here in the past so I won’t get into it again haha, but overall I do think it is a decent bio about the Borgia family. He did made an effort to present something new, and he does have at least a little bit of critical thinking about the sources which created the history of the Borgias as we know today, and also like I said before, I adore the structure of his book, how he intertwined the chapters about the Borgias with chapters about papal history/other noble families, it’s an engaging and interesting read.

The Borgias, Ivan Cloulas

Ok so, although his book reads like a gossip magazine with many unsubstantial claims, I feel I have to include him on this list only because his book begins with the Borgias from València and it goes back to Spain, with Juan’s son, arriving at Francisco de Borja, most commonly known as St. Francis Borgia. It’s one of the few books about the Borgia family where you have a more detailed account about these family members, and I like some of his thoughts about the descendants of Rodrigo Borgia and their shared similarities, being employed in different ways. It also has a cool chapter analysing the history of the Borgias through the centuries, I don’t agree with some of his conclusions, but I really enjoyed reading that chapter, so yeah.

The Borgia Chronicles: 1414-1572, Mary Hollingsworth

The reason I like her book is maybe precisely why some people don’t, I suppose, it is dry and it mainly sticks to presenting the information available about the family, instead of sensationalistic writing with a high dose of personal judgments and claims/narratives which don’t have enough (or any) evidence to back it up. That within the Borgia historical literature is a rare thing to find, overall Borgia authors seems more interested/concerned about showing the reader what they think about the family, and the many mysteries surrounding them, than actually laying out in an objective manner the historical material available, andletting the reader reach their own judgments and conclusions about it, you know. Hollingsworth, for the most part, tends to do the former in her book and refrains from doing the latter, so yeah there might be some mistakes iirc, and it’s not a book for everyone, but I do like it, and I find it a decent source to check/compare info about the Borgia family in the english language.

Non-Fiction books about Rodrigo Borgia, (Pope Alexander VI)

Material for a History of Pope Alexander VI, his relatives and his times, Peter de Roo.

The reason this one is on my list is because no matter how much we may agree or disagree with his presentation of Rodrigo, his life and his papacy, there is no denying he gathered an extensive, if not the most extensive, historical material about Rodrigo/his family and it’s amazing to read it. I also think he lays out his arguments in a very coherent way, attaching his evidence alongside it. His thought process is not all over the place, which is something I appreciate a lot when reading historical bios. He also does not throw Cesare under the bus in order to defend Rodrigo or explain his actions, De Roo is as just with Rodrigo as he is with Cesare, which it’s another rare thing to find with Borgia authors, especially Rodrigo’s authors.

Non-fiction books about Cesare Borgia

Cesare Borgia: Duca di Romagna, notizie e documenti raccolti e pubblicati, Edoard Alvisi.

I don’t even know what else to say about this biography without fangirling all over again lol, I’ll leave some of my thoughts while reading his bio that I posted here and here :)) and I will complement by saying it is my one and only favorite Borgia biography as well as the best one made about Cesare imo. Every time I remember Cesare has such a high quality historical work about his life, it warms my heart and I feel so grateful to il signore Alvisi, God bless his soul for the necessary, honest, historical work he did there.

Cesare Borgia: La Sua Vita, La Sua Famiglia, I Suoi Tempi, Gustavo Sacerdote.

The reason I include him is mostly because of his research, like it happens with de Roo, it is impossible to deny his excellent research about Cesare. Combined with Alvisi’s, you really do have all the available historical material about Cesare’s life, and it was great to be able to absorb so much information in an in-deepth way. I don’t have a good opinion about him as an historian, or as Cesare’s biographer, but as a researcher he is one of the best I’ve read, and the way in which he exposes his research should be the standard for any historical work imo. He was incredibly meticulous and made it a point to present as much of the official documents in their integrity as possible, instead of just selective bits. His bibliography is also a thing of beauty, super organized and thorough.

The Life of Cesare Borgia, Rafael Sabatini

The reason is, really, that I love his writing and his sense of humour. He is dramatic, but my kind of dramatic perhaps lol, and he rightly addresses the big double standards when it comes to the Borgia family (while they lived and even more so after their deaths, until Sabatini’s own day), as well as points out the flaws within the main primary sources about them, most of all: Cappello, Guicciardini and Sanuto, with a justified wave of indignation + amazing sarcasm which for me is satisfying to read. His examination of Gregorovius’ view and claims about Cesare, for example, it’s truly one of his best moments, so yeah, I have a fondness for his bio, even though I am aware of its flaws, and I mostly disagree with his personal view about Cesare as a man and his politics.

El Princípe del Renacimiento: Vida y Leyenda de César Borgia, José Catalán Deus

So, putting aside that I love reading in spanish and I find the spanish section of the Borgia historical literature quite interesting, actually, the reason I included this one is because, as far as I know, I think it is the best one in the spanish language about Cesare, it carries much of the flaws and vices of his historical literature, yes, but I do think it a decent bio. Also it was an important book for me when I read it at the time, because it made me re-think much of the claims and presentations made about the Borgia family by the previous authors I had read, and go deeper into the historical material to see if there was any evidence for it. I think much like Meyer, Catalán Deus also attempted to deliver something new, and advance in a way the way Cesare’s historical figure has been studied and presented, and I appreciate that effort, it’s one of the books I check info from time to time, too. Ps: it’s not on my top 10, I don’t like the book as a whole, but I can’t help but to add on this list Marion Johnson’s The Borgias, for one simple and superficial reason: the artwork is soooo pretty 💖 it’s hardcover with quality pages and beautiful coloured images, and to this day it is the most beautiful bio I own about the Borgias, so I had to say something djsdjsdjs, excuse me here. Andd I think those are it, anon?? it’s possible I might be forgetting some, I spent such a long time reading about them, it’s hard for me to remember all of the books, especially with my bad memory lol, but if I remember other ones later, I’ll reblog this and add to this list! Thank you for sending this ask, and I’m so sorry for the time I took to answer it! :( I hope you still see this <33

#anon ask#ask answered#house borgia in history#i feel i'm repeating myself here + my english is not as sharp as it used to be and there might some typos :(((#but anyways hope it's understandable lol

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Historiography of Philip II (2/2)

“Pero 1947 marcó el inicio de una nueva era – la era actual – de trabajo historiográfico sobre Felipe II, con la publicación simultánea de dos magníficas obras en las que se mostraba a Felipe como una persona y no como una personificación: El Mediterráneo de Fernand Braudel y Antonio Pérez de Gregorio Marañon.

Ambos autores escribieron la mayoría de sus obras maestras en el exilio (el primero siendo prisionero de guerra en Alemania, y el segundo en París); ambos exploraron en fuentes de archivo de todo el mundo para contar su historia, y ambos escribieron a gran escala y con prosa vibrante. Aunque su metodologías diferían en gran medida, Braudel y Marañon demostraron que la única forma fiable de estudiar a Felipe era la total inmersión en los documentos a fin de conocer el mundo del rey en toda su dimensión. (..)

Bajo la inspiración de estas obras emblemáticas, la producción de trabajos, libros, ensayos y artículos sobre el Rey Prudente y su mundo no ha dejado de aumentar desde entonces, hasta el punto de que en la década de 1990, cuando se aproximaba el cuarto centenario de la muerte del rey, se publicaron sobre este tema mas de 20.000 páginas impresas. Por nombrar sólo las tres monografías más importantes: José Luis Gonzalo Sánchez-Molero puso de relieve el desarrollo tanto de la sobresaliente erudición del rey como de su profunda fe religiosa; Fernando Checa retrató al rey como un coleccionista de inigualable gusto artístico, y José Antonio Escudero presentó a Felipe como un burócrata solitario pero eficiente. Sólo en 1998, aniversario del cuarto centenario, los investigadores españoles publicaron las actas de doce congresos, los catalógos de cinco importantes exposiciones y multitud de monografías, biografías y ediciones especiales de revistas y otros medios impresos, en su mayoría abrumadoramente positivas. En la maliciosamente ingeniosa frase de María José Rodríguez-Salgado, “los españoles quieren querer a Felipe II y recuperarle como uno más en el panteón familiar”.

También los extranjeros, ahora, “quieren querer a Felipe”. Michael de Ferdinandy (Felipe II, 1988) de Hungría; Ivan Cloulas (Felipe II, 1993) y Joseph Pérez (La España de Felipe II, 2000), de Francia; Peter Pierson (Felipe de España, 1998), de Estados Unidos; Patrick Williams (Philip II, 2001), de Inglaterra; Rosemarie Mulcahy, Felipe II de España, mecenas de las Artes (Dublín, 2004), de Irlanda. Todos ellos han escrito estudios sobre el rey mucho más favorables que los de ningún escritor extranjero anterior.”

“But 1947 marked the beginning of a new era – the current era – of historiographical work on Philip II, with the simultaneous publication of two magnificent works in which Philip was shown as a person and not as a personification: The Mediterranean by Fernand Braudel and Antonio Pérez by Gregorio Marañón.

Both authors wrote most of their masterpieces in exile (the former being a prisoner of war in Germany, and the latter in Paris); both explored archival sources from around the world to tell their story, and both wrote on a grand scale and in vibrant prose. Although their methodologies differed greatly, Braudel and Marañon showed that the only reliable way to study Philip was total immersion in the documents in order to understand the king's world in all its dimensions. (..)

Inspired by these emblematic works, the production of works, books, essays and articles on the Prudent King and his world has not stopped increasing since then, to the point that in the 1990s, when the fourth centenary of the king's death was approaching, more than 20,000 printed pages were published on this subject. To name just the three most important monographs: José Luis Gonzalo Sánchez-Molero highlighted the development of both the king's outstanding scholarship and his deep religious faith; Fernando Checa portrayed the king as a collector of unrivaled artistic taste, and José Antonio Escudero presented Philip as a reclusive but efficient bureaucrat. In 1998 alone, the anniversary of the fourth centenary, Spanish researchers published the proceedings of twelve congresses, the catalogs of five important exhibitions and a multitude of monographs, biographies and special editions of magazines and other printed media, the majority of which were overwhelmingly positive. In the maliciously ingenious phrase of María José Rodríguez-Salgado, "the Spanish want to love Philip II and recover him as one more in the family pantheon".

Foreigners also now "want to love Philip." Michael de Ferdinandy (Felipe II, 1988) from Hungary; Ivan Cloulas (Felipe II, 1993) and Joseph Pérez (La España de Felipe II, 2000) from France; Peter Pierson (Felipe de España, 1998) from the United States; Patrick Williams (Philip II, 2001) from England; Rosemarie Mulcahy (Philip II of Spain, patron of the arts, Dublin, 2004) from Ireland. All of them have written much more favorable studies of the king than any foreign writer before.”

Geoffrey Parker, Felipe II: La biografía definitiva

Translation: Google translator and me

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

La vita quotidiana nei castelli della Loira nel Rinascimento

La vita quotidiana nei castelli della Loira nel Rinascimento

Chi non ha mai sognato di passeggiare fra le immense sale da ballo, i sontuosi scaloni e le imponenti torri di un castello rinascimentale? Ma come si viveva in quei luoghi pieni di fascino – dove prese lentamente forma una nuova concezione di potere regio – nel XV e nel XVI secolo, tra il regno di Carlo VII e quello di Enrico IV? Ivan Cloulas apre le porte dei più famosi castelli della Loira, e…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

LAW # 15 : CRUSH YOUR ENEMY TOTALLY

JUDGEMENT

All great leaders since Moses have known that a feared enemy must be crushed completely. (Sometimes they have learned this the hard way.) If one ember is left alight, no matter how dimly it smoulders, a fire will eventually break out. More is lost through stopping halfway than through total annihilation: The enemy will recover, and will seek revenge. Crush him, not only in body but in spirit.

TRANSGRESSION OF THE LAW

No rivalry between leaders is more celebrated in Chinese history than the struggle between Hsiang Yu and Liu Pang. These two generals began their careers as friends, fighting on the same side. Hsiang Yu came from the nobility; large and powerful, given to bouts of violence and temper, a bit dull witted, he was yet a mighty warrior who always fought at the head of his troops. Liu Pang came from peasant stock. He had never been much of a soldier, and preferred women and wine to fighting; in fact, he was something of a scoundrel. But he was wily, and he had the ability to recognize the best strategists, keep them as his advisers, and listen to their advice. He had risen in the army through these strengths.

The remnants of an enemy can become active like those of a disease or fire. Hence, these should be exterminated completely.... One should never ignore an enemy, knowing him to be weak. He becomes dangerous in due course, like the spark of fire in a haystack.

KAUTILYA, INDIAN PHILOSOPHER, THIRD CENTURY B.C.

In 208 B.C., the king of Ch‘u sent two massive armies to conquer the powerful kingdom of Ch’in. One army went north, under the generalship of Sung Yi, with Hsiang Yu second in command; the other, led by Liu Pang, headed straight toward Ch’in. The target was the kingdom’s splendid capital, Hsien-yang. And Hsiang Yu, ever violent and impatient, could not stand the idea that Liu Pang would get to Hsien-yang first, and perhaps would assume command of the entire army.

THE TRAP AT SINIGAGLIA

On the day Ramiro was executed, Cesare [Borgia] quit Cesena, leaving the mutilated body on the town square, and marched south. Three days later he arrived at Fano, where he received the envoys of the city of Ancona, who assured him of their loyalty. A messenger from Vitellozzo Vitelli announced that the little Adriatic port of Sinigaglia had surrendered to the condottieri [mercenary soldiers]. Only the citadel, in charge of the Genoese Andrea Doria, still held out, and Doria refused to hand it over to anyone except Cesare himself. [Borgia] sent word that he would arrive the next day, which was just what the condottieri wanted to hear. Once he reached Sinigaglia. Cesare would be an easy prey, caught between the citadel and their forces ringing the town.... The condottieri were sure they had military superiority, believing that the departure of the French troops had lef? Cesare with only a small force.

In fact, according to Machiavelli. [Borgia] had left Cesena with ten thousand infantry-men and three thousand horse, taking pains to split up his men so that they would march along parallel routes before converging on Sinigaglia. The reason for such a large force was that he knew, from a confession extracted from Ramiro de Lorca, what the condottieri had up their sleeve. He therefore decided to turn their own trap against them. This was the masterpiece of trickery that the historian Paolo Giovio later called “the magnificent deceit. ” At dawn on December 31 [1502], Cesare reached the outskirts of Sinigaglia.... Led by Michelotto Corella, Cesare’s advance guard of two hundred lances took up its position on the canal bridge.... This control of the bridge effectively prevented the conspirators’ troops from withdrawing....

Cesare greeted the condottieri effusively and invited them to join him.... Michelotto had prepared the Palazzo Bernardino for Cesare’s use, and the duke invited the condottieri inside.... Once indoors the men were quietly arrested by guards who crept up from the rear.... [Cesare] gave orders for an attack on Vitelli’s and Orsini’s soldiers in the outlying areas.... That night, while their troops were being crushed, Michelotto throttled Oliveretto and Vitelli in the Bernardino palace.... At one fell swoop, [Borgia] had got rid of his former generals and worst enemies.

THE BORGIAS, IVAN CLOULAS, 1989

At one point on the northern front, Hsiang’s commander, Sung Yi, hesitated in sending his troops into battle. Furious, Hsiang entered Sung Yi’s tent, proclaimed him a traitor, cut off his head, and assumed sole command of the army. Without waiting for orders, he left the northern front and marched directly on Hsien-yang. He felt certain he was the better soldier and general than Liu, but, to his utter astonishment, his rival, leading a smaller, swifter army, managed to reach Hsien-yang first. Hsiang had an adviser, Fan Tseng, who warned him, “This village headman [Liu Pang] used to be greedy only for riches and women, but since entering the capital he has not been led astray by wealth, wine, or sex. That shows he is aiming high.”

Fan Tseng urged Hsiang to kill his rival before it was too late. He told the general to invite the wily peasant to a banquet at their camp outside Hsien-yang, and, in the midst of a celebratory sword dance, to have his head cut off. The invitation was sent; Liu fell for the trap, and came to the banquet. But Hsiang hesitated in ordering the sword dance, and by the time he gave the signal, Liu had sensed a trap, and managed to escape. “Bah!” cried Fan Tseng in disgust, seeing that Hsiang had botched the plot. “One cannot plan with a simpleton. Liu Pang will steal your empire yet and make us all his prisoners.”

Realizing his mistake, Hsiang hurriedly marched on Hsien-yang, this time determined to hack off his rival’s head. Liu was never one to fight when the odds were against him, and he abandoned the city. Hsiang captured Hsien-yang, murdered the young prince of Ch’in, and burned the city to the ground. Liu was now Hsiang’s bitter enemy, and he pursued him for many months, finally cornering him in a walled city. Lacking food, his army in disarray, Liu sued for peace.

Again Fan Tseng warned Hsiang, “Crush him now! If you let him go again, you will be sorry later.” But Hsiang decided to be merciful. He wanted to bring Liu back to Ch’u alive, and to force his former friend to acknowledge him as master. But Fan proved right: Liu managed to use the negotiations for his surrender as a distraction, and he escaped with a small army. Hsiang, amazed that he had yet again let his rival slip away, once more set out after Liu, this time with such ferocity that he seemed to have lost his mind. At one point, having captured Liu’s father in battle, Hsiang stood the old man up during the fighting and yelled to Liu across the line of troops, “Surrender now, or I shall boil your father alive!” Liu calmly answered, “But we are sworn brothers. So my father is your father also. If you insist on boiling your own father, send me a bowl of the soup!” Hsiang backed down, and the struggle continued.

A few weeks later, in the thick of the hunt, Hsiang scattered his forces unwisely, and in a surprise attack Liu was able to surround his main garrison. For the first time the tables were turned. Now it was Hsiang who sued for peace. Liu’s top adviser urged him to destroy Hsiang, crush his army, show no mercy. “To let him go would be like rearing a tiger—it will devour you later,” the adviser said. Liu agreed.

Making a false treaty, he lured Hsiang into relaxing his defense, then slaughtered almost all of his army. Hsiang managed to escape. Alone and on foot, knowing that Liu had put a bounty on his head, he came upon a small group of his own retreating soldiers, and cried out, “I hear Liu Pang has offered one thousand pieces of gold and a fief of ten thousand families for my head. Let me do you a favor.” Then he slit his own throat and died.

Interpretation

Hsiang Yu had proven his ruthlessness on many an occasion. He rarely hesitated in doing away with a rival if it served his purposes. But with Liu Pang he acted differently. He respected his rival, and did not want to defeat him through deception; he wanted to prove his superiority on the battlefield, even to force the clever Liu to surrender and to serve him. Every time he had his rival in his hands, something made him hesitate—a fatal sympathy with or respect for the man who, after all, had once been a friend and comrade in arms. But the moment Hsiang made it clear that he intended to do away with Liu, yet failed to accomplish it, he sealed his own doom. Liu would not suffer the same hesitation once the tables were turned.

This is the fate that faces all of us when we sympathize with our enemies, when pity, or the hope of reconciliation, makes us pull back from doing away with them. We only strengthen their fear and hatred of us. We have beaten them, and they are humiliated; yet we nurture these resentful vipers who will one day kill us. Power cannot be dealt with this way. It must be exterminated, crushed, and denied the chance to return to haunt us. This is all the truer with a former friend who has become an enemy. The law governing fatal antagonisms reads: Reconciliation is out of the question. Only one side can win, and it must win totally.

Liu Pang learned this lesson well. After defeating Hsiang Yu, this son of a farmer went on to become supreme commander of the armies of Ch‘u. Crushing his next rival—the king of Ch’u, his own former leader—he crowned himself emperor, defeated everyone in his path, and went down in history as one of the greatest rulers of China, the immortal Han Kao-tsu, founder of the Han Dynasty.

To have ultimate victory, you must be ruthless.

NAPOLEON BONAPARTE, 1769-1821

Those who seek to achieve things should show no mercy.

Kautilya, Indian philosopher third century B.C.

OBSERVANCE OF THE LAW

Wu Chao, born in A.D. 625, was the daughter of a duke, and as a beautiful young woman of many charms, she was accordingly attached to the harem of Emperor T’ai Tsung.

The imperial harem was a dangerous place, full of young concubines vying to become the emperor’s favorite. Wu’s beauty and forceful character quickly won her this battle, but, knowing that an emperor, like other powerful men, is a creature of whim, and that she could easily be replaced, she kept her eye on the future.

Wu managed to seduce the emperor’s dissolute son, Kao Tsung, on the only possible occasion when she could find him alone: while he was relieving himself at the royal urinal. Even so, when the emperor died and Kao Tsung took over the throne, she still suffered the fate to which all wives and concubines of a deceased emperor were bound by tradition and law: Her head shaven, she entered a convent, for what was supposed to be the rest of her life. For seven years Wu schemed to escape. By communicating in secret with the new emperor, and by befriending his wife, the empress, she managed to get a highly unusual royal edict allowing her to return to the palace and to the royal harem. Once there, she fawned on the empress, while still sleeping with the emperor. The empress did not discourage this—she had yet to provide the emperor with an heir, her position was vulnerable, and Wu was a valuable ally.

In 654 Wu Chao gave birth to a child. One day the empress came to visit, and as soon as she had left, Wu smothered the newborn—her own baby. When the murder was discovered, suspicion immediately fell on the empress, who had been on the scene moments earlier, and whose jealous nature was known by all. This was precisely Wu’s plan. Shortly thereafter, the empress was charged with murder and executed. Wu Chao was crowned empress in her place. Her new husband, addicted to his life of pleasure, gladly gave up the reins of government to Wu Chao, who was from then on known as Empress Wu.

Although now in a position of great power, Wu hardly felt secure. There were enemies everywhere; she could not let down her guard for one moment. Indeed, when she was forty-one, she began to fear that her beautiful young niece was becoming the emperor’s favorite. She poisoned the woman with a clay mixed into her food. In 675 her own son, touted as the heir apparent, was poisoned as well. The next-eldest son—illegitimate, but now the crown prince—was exiled a little later on trumped-up charges. And when the emperor died, in 683, Wu managed to have the son after that declared unfit for the throne. All this meant that it was her youngest, most ineffectual son who finally became emperor. In this way she continued to rule.

Over the next five years there were innumerable palace coups. All of them failed, and all of the conspirators were executed. By 688 there was no one left to challenge Wu. She proclaimed herself a divine descendant of Buddha, and in 690 her wishes were finally granted: She was named Holy and Divine “Emperor” of China.

Wu became emperor because there was literally nobody left from the previous T’ang dynasty. And so she ruled unchallenged, for over a decade of relative peace. In 705, at the age of eighty, she was forced to abdicate.

Interpretation

All who knew Empress Wu remarked on her energy and intelligence. At the time, there was no glory available for an ambitious woman beyond a few years in the imperial harem, then a lifetime walled up in a convent. In Wu’s gradual but remarkable rise to the top, she was never naive. She knew that any hesitation, any momentary weakness, would spell her end. If, every time she got rid of a rival a new one appeared, the solution was simple: She had to crush them all or be killed herself. Other emperors before her had followed the same path to the top, but Wu—who, as a woman, had next to no chance to gain power—had to be more ruthless still.

Empress Wu’s forty-year reign was one of the longest in Chinese history. Although the story of her bloody rise to power is well known, in China she is considered one of the period’s most able and effective rulers.

A priest asked the dying Spanish statesman and general Ramón Maria Narváez. (1800-1868), “Does your Excellency forgive all your enemies ? ”I do not have to forgive my enemies,” answered Narváez, ”I have had them all shot. ”

KEYS TO POWER

It is no accident that the two stories illustrating this law come from China: Chinese history abounds with examples of enemies who were left alive and returned to haunt the lenient. “Crush the enemy” is a key strategic tenet of Sun-tzu, the fourth-century-B.C. author of The Art of War. The idea is simple: Your enemies wish you ill. There is nothing they want more than to eliminate you. If, in your struggles with them, you stop halfway or even three quarters of the way, out of mercy or hope of reconciliation, you only make them more determined, more embittered, and they will someday take revenge. They may act friendly for the time being, but this is only because you have defeated them. They have no choice but to bide their time.

The solution: Have no mercy. Crush your enemies as totally as they would crush you. Ultimately the only peace and security you can hope for from your enemies is their disappearance.

Mao Tse-tung, a devoted reader of Sun-tzu and of Chinese history generally, knew the importance of this law. In 1934 the Communist leader and some 75,000 poorly equipped soldiers fled into the desolate mountains of western China to escape Chiang Kai-shek’s much larger army, in what has since been called the Long March.

Chiang was determined to eliminate every last Communist, and by a few years later Mao had less than 10,000 soldiers left. By 1937, in fact, when China was invaded by Japan, Chiang calculated that the Communists were no longer a threat. He chose to give up the chase and concentrate on the Japanese. Ten years later the Communists had recovered enough to rout Chiang’s army. Chiang had forgotten the ancient wisdom of crushing the enemy; Mao had not. Chiang was pursued until he and his entire army fled to the island of Taiwan. Nothing remains of his regime in mainland China to this day.

The wisdom behind “crushing the enemy” is as ancient as the Bible: Its first practitioner may have been Moses, who learned it from God Himself, when He parted the Red Sea for the Jews, then let the water flow back over the pursuing Egyptians so that “not so much as one of them remained.” When Moses returned from Mount Sinai with the Ten Commandments and found his people worshipping the Golden Calf, he had every last offender slaughtered. And just before he died, he told his followers, finally about to enter the Promised Land, that when they had defeated the tribes of Canaan they should “utterly destroy them... make no covenant with them, and show no mercy to them.”

The goal of total victory is an axiom of modern warfare, and was codified as such by Carl von Clausewitz, the premier philosopher of war. Analyzing the campaigns of Napoleon, von Clausewitz wrote, “We do claim that direct annihilation of the enemy’s forces must always be the dominant consideration.... Once a major victory is achieved there must be no talk of rest, of breathing space... but only of the pursuit, going for the enemy again, seizing his capital, attacking his reserves and anything else that might give his country aid and comfort.” The reason for this is that after war come negotiation and the division of territory. If you have only won a partial victory, you will inevitably lose in negotiation what you have gained by war.

The solution is simple: Allow your enemies no options. Annihilate them and their territory is yours to carve. The goal of power is to control your enemies completely, to make them obey your will. You cannot afford to go halfway. If they have no options, they will be forced to do your bidding. This law has applications far beyond the battlefield. Negotiation is the insidious viper that will eat away at your victory, so give your enemies nothing to negotiate, no hope, no room to maneuver. They are crushed and that is that.

Realize this: In your struggle for power you will stir up rivalries and create enemies. There will be people you cannot win over, who will remain your enemies no matter what. But whatever wound you inflicted on them, deliberately or not, do not take their hatred personally. Just recognize that there is no possibility of peace between you, especially as long as you stay in power. If you let them stick around, they will seek revenge, as certainly as night follows day. To wait for them to show their cards is just silly; as Empress Wu understood, by then it will be too late.

Be realistic: With an enemy like this around, you will never be secure. Remember the lessons of history, and the wisdom of Moses and Mao: Never go halfway.

It is not, of course, a question of murder, it is a question of banishment. Sufficiently weakened and then exiled from your court forever, your enemies are rendered harmless. They have no hope of recovering, insinuating themselves and hurting you. And if they cannot be banished, at least understand that they are plotting against you, and pay no heed to whatever friendliness they feign. Your only weapon in such a situation is your own wariness. If you cannot banish them immediately, then plot for the best time to act.

Image: A Viper crushed beneath your foot but left alive, will rear up and bite you with a double dose of venom. An enemy that is left around is like a half-dead viper that you nurse back to health. Time makes the venom grow stronger.

Authority: For it must be noted, that men must either be caressed or else annihilated; they will revenge themselves for small injuries, but cannot do so for great ones; the injury therefore that we do to a man must be such that we need not fear his vengeance. (Niccolò Machiavelli, 1469-1527)

REVERSAL

This law should very rarely be ignored, but it does sometimes happen that it is better to let your enemies destroy themselves, if such a thing is possible, than to make them suffer by your hand. In warfare, for example, a good general knows that if he attacks an army when it is cornered, its soldiers will fight much more fiercely. It is sometimes better, then, to leave them an escape route, a way out. As they retreat, they wear themselves out, and are ultimately more demoralized by the retreat than by any defeat he might inflict on the battlefield. When you have someone on the ropes, then—but only when you are sure they have no chance of recovery—you might let them hang themselves. Let them be the agents of their own destruction. The result will be the same, and you won’t feel half as bad.

Finally, sometimes by crushing an enemy, you embitter them so much that they spend years and years plotting revenge. The Treaty of Versailles had such an effect on the Germans. Some would argue that in the long run it would be better to show some leniency. The problem is, your leniency involves another risk—it may embolden the enemy, which still harbors a grudge, but now has some room to operate. It is almost always wiser to crush your enemy. If they plot revenge years later, do not let your guard down, but simply crush them again.

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A prince of both France and Italy,solemnly invested with the temporal power of the Holy See, Cesare had now outstripped his dead brother, Juan of Gandia, in honors.What had promoted his extraordinary rise was the fierce determination that made him scorn the easy path of a Church dignitary and opt instead for the adventurous career of a conqueror. He would now show himself to the world as the complete Renaissance man. At twenty-five, he had tasted every pleasure,passed every test,used murder as a means to his desired ends. Intelligent and cunning, ambitious and totally unscrupulous, his courage and resolve were equaled only by the strength and skill he was so fond of displaying. His physical prowess aroused the jealousy of other men and infatuation of the opposite sex. A consummate athlete,one feast day he sprang into an arena set up on St. Peter's square and took on five bulls,one after another,dispatching them all. The crowd roared when he sliced off the head of one beast with a single blow. Such feats made him a matchless hero,one whom the young men looked up to as their leader.

Ivan Cloulas - The Borgias

Cesare Borgia - 3x06

29 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Cesare should be totally satisfied with this victory, but he worries about his sister's health. She is bedridden and depressed, having given birth to a stillborn. Of course, he tried to comfort her in the letter that came after Camerino's fall.

Ivan Cloulas - Cesare Borgia (Son of Pope, Prince and Adventurer)

#cesare borgia#lucrezia borgia#quote#book#books#ivan cloulas#i love them with all my heart#they never forgot each other tbh#and this family is always too much for me#~~bye#light of my life#my man

8 notes

·

View notes

Quote

On Monday, September 6, two buffoons circulated around the city. One of them, to whom Lucrezia had given the fringed brocade dress, which was worth about 300 ducats and had worn for the first and only time the day before, rode all the streets and main squares of the city, shouting loudly: 'Long live the illustrious Duchess of Ferrara, long live Pope Alexander!'

Ivan Cloulas - Cesare Borgia (Son of Pope, Prince and Adventurer)

#lucrezia borgia#light of my life#rodrigo borgia#quote#ivan cloulas#book#books#i'm sorry but...#SAME

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

On Monday, the last day of August, the magnificent lady Lucrezia, formerly of Aragon, the pope's daughter, left the city to go to Nepi, accompanied by about 600 knights.

Ivan Cloulas - Cesare Borgia (Son of Pope, Prince and Adventurer)

#cesare borgia#ivan cloulas#lucrezia borgia#quote#book#books#burckard says ~~~magnificent and i'm like...#I KNOW !!!!!!#ugh#light of my life

23 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Two days later, it is with a pour rain that Cesare and his army enter the walls [of Forli]. Despising these inhabitants who delivered the city without resistance, the victorious soldiers abandon themselves without shame to the plunder and rob the citizens [...] Pragmatic, Cesare begins by punishing the soldiers guilty of the exactions. By this act, he would atone the citizens to his cause.

Ivan Cloulas - Cesare Borgia (Son of Pope, Prince and Adventurer)

#cesare borgia#ivan cloulas#book#books#quote#i'm sorry but...#I'M DYING#jfeijfiejfijer#i can't deal with him tbh#~~cesare begins by punishing the soldiers guilty of the exactions#he would atone the citizens to his cause#THE PRINCE#btw i feel like machiavelli freaking out over him#~~bye#my man

15 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Cesare's luck seems to be smiling now in all its fullness. The French prince, his military alliances, the defeat of Ludovico the Moor, and his capture in April, as well as his new status as gonfalonier , are as many signs that his design will be fulfilled: conquer Romangna to make it a principality.

Ivan Cloulas - Cesare Borgia (Son of Pope, Prince and Adventurer)

#cesare borgia#ivan cloulas#book#books#quote#i'm sorry#but this is too much for me#jifejifjeifjer#his superiority is shameless#!!!!!!!!!!!#my man

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

ivan cloulas describes cesare's hair as “copper”, in addition to a short beard - i wonder how copper was his hair or even blond ????? which is strange, since the image of black hair prevails in my mind, hm... but i was expecting this description, for sure @ducavalentinos

12 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Lucrezia is officially invested with the powers of governor [of Spoleto] for five months, together with her brother Cesare. There, the 19-year-old quickly assumes her responsibilities by organizing a law enforcement force, promoting justice and pacifying her surroundings.

Ivan Cloulas - Cesare Borgia (Son of Pope, Prince and Adventurer)

#cesare borgia#lucrezia borgia#ivan cloulas#quotes#book#books#TELL THEM MY QUEEN <3#light of my life#ugh

9 notes

·

View notes