#In so she becomes like the summer itself: oppressive yet golden

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

In case if I don't drop this big ass character analysis on Kallen Kozuki and Aki Izayoi, then here's why I don't think they're the same person:

Kallen is a spring knight.

Aki is a summer witch.

That is all.

#code geass#yugioh 5ds#aki izayoi#kallen kozuki#kallen stadtfeld#akiza izinski#going absolutely mad baker over here with this shit#Like if I know that yugioh definitely rip off the design#but their character arcs are like the inverse of each other#trust me i'm cooking#like kallen's entire arc is that of a knight#fealty over your lord vs. doing what's right#not caring what happens to you as long as your lord or the objective is taken care of#a force of change for the world#as the spring itself#meanwhile Aki is the witch in the dark corners of the fairytales#The one who will destroy you#Aki also never cared about herself because she was so angry at world while also not wanting to hurt others anymore#aki's arc is to give into being a witch or decide to be the party's mage#In so she becomes like the summer itself: oppressive yet golden#also think about the masks they carry#Aki's mask is being the witch who wants to hurt others#who takes great pleasure in it#while kallen's mask is a sickly school girl who is sheltered and very naive#Like none of these are wrong#Aki does feel that anger and Kallen is slightly naive#but they almost reflect each other's true selves#it's so good#even the flaws of their writing is the inverse#we never delve deeper into Kallen's personal life

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 Things Intersex Folks Need to Know About How We Perpetuate Anti-Black Racism

1. The Segregation in Our Intersex Movement Is Real

The intersex movement has been mostly white since day one. Consequently, it’s necessary to ask ourselves if we’ve inadvertently created an atmosphere that urges Black intersex people to put aside their Blackness — and the oppression linked to it — in order to focus on our collective goals.

In creating this type of environment, it appears our community hasn’t yet been able to connect the dots between Black and intersex people’s oppression — which Saifa reminded me are both rooted in state violence — and our liberation.

Black intersex folks who’ve lived in isolation and have dealt with segregation in their daily lives shouldn’t have to contend with similar experiences once they’ve finally found, and entered our community.

I’m not talking about highly visible institutionalized segregation like the Jim Crow era when Saifa’s uncle, who was also intersex, was forced to sleep outside on the porch of his hospital after a surgery.

I’m talking about the low-key, harder to detect, segregation.

The kind that just takes for granted that the majority of people in the room will always be white. The type that may have a few Black and Brown faces sprinkled here and there, but on a vanilla frosted cake. Is there a path forward?

Sean Saifa Wall, a Black trans intersex activist and collage artist based in Atlanta, reflected on this question by looking back on his time spent as the former board president of an intersex non-profit. Saifa captured why increasing representation shouldn’t be the endgame.

“I think I made the mistake of thinking we need more people of color… but what does institutionalized white supremacy do? It brings in Black or Brown faces who won’t challenge white supremacy — and that’s how white supremacy perpetuates itself. You don’t need white folks to perpetuate it, you just need folks who are invested in white supremacy.”

When I was younger and mistakenly believing that whiteness was the norm to strive towards, I ended up internalizing racist ideologies and, as a result, never fully connected on a truly deep BFF level with my Black friends. Perhaps our movement, and its longstanding quest for acceptance, has created a similar divide.

The global intersex activist network consists, to my knowledge, of less than only 5 Black intersex activists. One of them is Saifa.

2. One’s Race and Intersex Identity Overlap

Born amidst racist flames that attempted to level his neighborhood, Saifa was brought up whilst his borough, The Bronx, was attempting to rebuild itself.

“When I was younger,” Saifa recounted, “I realized I had a different body. Then, due to interactions with NYPD, I was made to know that I was different in another way as well.”

As he got older, Saifa came out as queer, intersex, and trans to a mother — and a world — who wasn’t always ready or eager to respect his intersecting identities. Regardless, his Blackness, sexuality, and intersex identity were always interwoven.

“I cannot separate my intersex identity from my Black identity,” Saifa said. And he shouldn’t have to.

Unfortunately, I’m afraid our community hasn’t figured out ways yet to allow people to show up as their whole selves.

For instance, on the international level, it’s become a known issue that intersex activists from African countries don’t get similar amounts of representation, or speaking time at gatherings. And nationally, our support group meetings rarely, if ever, have been led by Black intersex folks or had sessions dedicated solely for Black intersex community members to come together.

It’s only in the past few years that single Black folks are sitting on boards, or in staff positions of our organizations. There’s also never been, to my knowledge, any Black clinicians present at our Continuing Medical Education (CME) sessions that happen before our support group conferences each year.

Race, especially as it relates to anti-blackness, feels as though it’s at times an elephant in the room.

For me, this elephant peeped its head out when I realized it had become a tradition for one of our non-Black community members, who I love and cherish dearly, to sing Macy Gray’s “I Try” — in Gray’s uniquely raspy voice — at the annual talent show, which is supposed to provide a fun contrast to the rest of the conference.

The audience, if it’s a diverse year, might have a handful of Black folks. This year, there was only one person. I can’t imagine how isolating that experience might have been for them.

And this bring me back to the story I shared at the beginning, about the person who had Obama on a hit list.

Often, racism perpetuates itself by wearing the mask of a “joke” or “fun,” but racism is never a joke and the mask just presents one more hurdle in calling racism out.

It’s time us non-Black intersex people become more aware of our whiteness problem.

We need to keep having difficult conversations about race and oppression every step of the way.

Most importantly, we need to show up the few Black intersex people we do have in our small community, and check in with them to see if there’s anything else we could be doing to have their back.

We can challenge white supremacy in our movement just by asking Black intersex folks in our community what they need to feel safer in our collective spaces.

For our movement to be successful, it’s imperative that Black intersex folks feels they can participate as whole persons.

3. We’ve All Been Dehumanized

The list of atrocities against people of color, especially Black folks, carried out by the medical industrial complex and other agents includes: “the father of gynecology” using enslaved Black people as surgical research subjects, being disproportionately targeted by the US’s eugenic sterilization program that served as a catalyst for Nazi Germany’s and today’s “population control”policies, and the shackling of pregnant women inmates — who are disproportionately Black — in labor delivering children whom they most likely will be immediately separated from.

Likewise, intersex people have been rendered hermaphrodites and featured in freak shows, gawked at as monsters to at on TV, disproportionately put up for adoption, pumped with artificial hormones, robbed of their reproductive organs and genitalia, selectively aborted, raped, and brutally murdered.

Lynnell, a Black intersex lesbian activist, was born intersex but raised male by a single mother in a low-income household. She grew up in Chicago’s mostly Black, hypersegregated, South Side where her family — unlike mine on the North Side — was forced to deal with the effects of the city’s racist public policy and divestment responsible for the destruction of local economies, public schools and affordable housing.

Hyde Park, a pocket of wealth and whiteness on the South Side and home to the University of Chicago (UofC) Hospital, is where Lynnell’s mother took her as a child for doctor appointments.

Lynnell shared memories of that time stating, “My mom wasn’t given the tools she needed to make informed decisions.” As Lynnell grew older, she also “wasn’t taken seriously at first by [her doctors] either.”

Low-income and single mothers of color, labelled unfit by society, experience discrimination. Lynnell’s mother went to U of C seeking care, not charity, for her child. Seeing a golden opportunity, Lynnell’s doctors manipulated her mother’s financial status and turned the situation into a charity case anyway.

“They told my mom they were doing her a favor because they weren’t charging her.” In the doctor’s mind, they were participating in an equal trade with Lynnell and her mother.

To Lynnell, it was torture. “For eight years, every summer, for at least a month, I was put on different drugs, experimented on, given unnecessary procedures and manipulated.”

Exploitation of marginalized people by the MIC for their gains, especially in teaching environments, has been well-documented. Exploitation specific to Black intersex patients has yet to be researched. Lynnell’s doctors, I imagine, took one look at Lynnell’s mother and decided a poor Black woman wasn’t powerful enough stop what they had in store for Lynnell.

“I don’t know many white people that were used as guinea pigs like me,” Lynnell said.

4. Doctor’s Aren’t the Only People Attempting to Erase ‘Difference’

Intersex people are pretty familiar with secrecy, shame and stigma thanks to the pathologization of our bodies. As such, it’s important we have spaces to process our stories with each other. Yet, it’s important to note that as oppressed people, we are still capable of participating in the oppressing others.

The few times I’ve witnessed our community attempt to break down white supremacy and talk about racism, white intersex people successfully shifted the conversation, almost immediately, back to a conversation that centers them and their experience with intersex oppression.

Spaces where intersex people get together and talk are rare, so it makes sense why someone would want to relate and process, but in doing so, we are inadvertently preventing Black intersex folks in our community from expressing their unique experiences.

Saifa recounted a time when he “was trying to bring up the topics of anti-oppression, racism, etc., in the movement and people lost their damn minds. People were like, ‘we cannot hear it.’”

He also shared, “Anti-black racism showed up when I went to South Carolina on behalf of the MC case [a lawsuit involving the parents of a young Black intersex boy and his doctors] and one of the lawyers was condescending, talking down to me as the only Black person in the room. I was constantly pushing back against his patriarchy and racism.”

He continued, “I feel like people don’t care about issues related to anti-black racism in the intersex community.

“I think there’s some intersex people who really see those intersections, who really are affirming of people of color, but for the large part I feel that the level of anti-black racism awareness ranges from hostility to apathy.”

I asked if people ever seemed to care and he replied, “When funding is involved. That’s when people start to care more. Or, when a group wants some representation of diversity—but I found they wanted a Black face, but weren’t necessarily committed to issues around anti-Black racism.”

As a movement, we can’t only focus on these issues when funding dollars are at stake. That tokenizes Black folks.

Instead, we have to stitch anti-Black racism training, and education around white supremacy, into the fabric of our work together.

Saifa pointed out, “In the world, I’m confronted with anti-Blackness, and it’s par for the course, but it’s particularly more devastating when it’s from intersex people. Why? Because I think, ‘Oh, you understand.’

“Or at least I think they understand, until they say or do things that’s really racist and are unapologetic about their racism.”

5. We Need an Intersectional Analysis to Combat Racist Stereotypes

One of the white people present at Lynnell’s first intersex support group meeting recently told her that she was “afraid” of her at first, “because [Lynnell] had on leather and dark sunglasses.”

I asked Lynnell why she entered that support group meeting dressed in leather, sunglasses, and the rest of her leather daddy alter ego outfit. She responded, “Because I was the only Black intersex person there.”

Lynnell shouldn’t have to feel the need to protect herself like that in a room that was supposed to feel like home, a room where she was supposed to be able to let her guard down amongst people with similar experiences.

Unfortunately, this is the type of thing that can happen when a community doesn’t have a firm commitment to operating with an intersectional lens — one that places its most marginalized folks at the center.

Lynnell needed to protect herself at a support group, and in doing so, made a white person feel afraid, circles back to my main point.

We need to place Black intersex folks and their particular needs, struggles and desires at the front and center of our intersex activism.

If we don’t, we risk ostracizing Black intersex folks, again, within spaces meant to be a reprieve from shame and stigma.

6. Confronting White Supremacy Means Confronting Disembodiment

Disembodiment, or feeling detached from your body, often happens as a coping mechanism in response to intense trauma. Intersex activist, Mani Mitchell, once described it as feeling like a “floating head tugging around a body.”

Saifa, someone I admire for their commitment to somatic healing work, believes that white supremacy is rooted in disembodiment “because you have to be disembodied in order to not allow your self to be impacted by the inequity or suffering of others.”

Regardless, Saifa thinks it’s “imperative that white intersex activists feel their feelings regarding any shame they may have as they interrogate white supremacy and its brutal history.”

“It’s only fair that white intersex activists start to acknowledge, as much as their embodiment can hold, the shameful and disgusting emotions that come up after hearing the bitter truth and realities of Black folks and people of color.”

“Doing this work is difficult,” he acknowledged, “and it can bring up things we’d rather not have to face about ourselves.”

Still, non-Black intersex folks need to “confront those feelings and allow themselves to be impacted, then hopefully they can be motivated to action, and allow that empowerment to impact others.”

In taking Saifa’s advice, we can create positive ripple effects throughout our whole community. Doing the work to steer our movement towards becoming an intersectional, anti-racist, intersex movement is a win-win for everyone involved!

218 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lone Camellia.

“Never forget what you are, for surely the world will not. Make it your strength. Then, it can never be your weakness.” – George R.R. Martin

It was a misty morning that first brought her to him.

He was treading the lands as he always did, moving as if a ghost through the forests that he had called home then. She approached him from the fog that wove between the trees, though he had caught her scent long before she appeared. Witless and lanced through with the sweat of determination, the distinct twinge of someone looking for something. It made his nose wrinkle in disdain.

When her verdant eyes settled on him, he had stopped while standing aloft the roots of a great tree. It provided the height from which he towered before her, not that he wasn’t already so tall. Yet, she had more height than he had expected for one so meager in figure. She’d dropped to her knees in deference to the Great Dog Prince, reducing herself from the gazelle-like stature she held.

“You are Lord Sesshoumaru, are you not?” she’d said simply, swallowing hard against her innate fear. Indeed, he conceded she was brave to approach him; he was sure her instincts were screaming out against her choice.

He didn’t answer her right away, golden eyes slanted downwards to appraise her through the morning mist, and darkness of the forest. She didn’t move, didn’t dare to raise her face to him again after she had taken her vulnerable position.

“What do you want with me?” he said curtly.

“Please, o Lord of the Western Lands. I’ve sought you to train me,” she proclaimed, finally lifting her head to beseech him properly. He could now clearly see the green markings that stood shockingly vibrant against her tan skin. He’d already known what she was when her scent met him, but the gentle, light freckles that sprinkled their way over her shoulders and face identified her as a deer youkai. Strange that one should be this far in the mountains, he mused idly.

“What for and why should I?”

She swallowed again.

“My family has been slain by humans, my lord. Not one is left of them but me, and I wish to be powerful, like you,” she stopped to let herself grimace as if struck by the memory. “Please, I do not wish to die. I am tired of being weak.”

A low huff.

“That is none of my concern.”

With that he’d sprung off the roots of the tree, sailing over her folded figure to land behind her. His landing barely shifted the moss beneath his feet. She’d frozen, as her kind were wont to do, and now did not turn to face him again. He’d started walking away, determined to move on in his patrol, when a vine caught his foot. That vine had not been there before, he’d thought, as he sliced it away without preamble. More of them started to manifest from the same spot to cling like the worried hands of children to his boot as if their kin had not just been cut down in its prime but seconds ago.

He growled his disapproval as he turned to glower at the culprit, knowing well who was daring to show such disregard for their own life. The deer appeared more spirited now as her youki thrummed from her hands that were planted firmly to the ground in front of her, pulsing towards him. Defiance colored her expression.

“I apologize, my lord,” she said as her energy waned off into the passive force it had been previously. “Please forgive my insolence, but I wish nothing more than to become strong! I know I have not fangs or claws – but there must be some way,” she grew quieter as she spoke, voice breaking as a shudder ran through her. Yes, it was as he’d thought earlier. Her instincts were wisely rebelling against her very unwise decisions. He continued to glare out of the side of his eyes at her. To his surprise, she spoke again as he assessed his next move.

“Are you not the protector of these lands? My lord, will you truly allow these humans to get away with the slaughter of other demons when our numbers dwindle so?”

It was then that whatever small, fragile pity he had for her had worn out. He stalked forward to grab her by the collar of her furisode, anger flashing in his amber gaze. Hauling her up to face him, he dug his claws in the silk fabric of her clothing. Poison mingled at his claw tips, singeing the delicate material where it touched. The hind flinched away from his eyes, but not his grip.

“Your clear lack of self-preservation proves that you serve no use to me,” he rumbled low in his throat before letting her go harshly. She caught herself, refusing to stumble before him it seemed. “The plight of lesser demons does not concern me. Do not question my honor as such.”

He turned on his heels away from her. He had grown tired of this meeting and its sole occupant. With long strides, he began back into the forest, hoping to leave the deer behind this time.

As he walked along, he scowled to himself. He turned over her words a few times in his mind, marveling on it like a small pebble. Her comment had rankled him. He was indeed the guardian of the Western Lands as his father had been before him, however, the times had changed. Humans encroached, and more and more their distaste of demons grew palpable. Their gunpowder burned his nose, their settlements stole his territory, their noisiness irritated his hearing. He had resigned himself to the fact that the burden of his duties that his father had passed to him had transformed itself into another beast that dug its claws deeper and deeper into his back as the decades passed.

He did not need reminding by a lowly doe of that which he was well aware.

He continued deeper into the trees, but he was aware he was being followed. Low anger simmered beneath the surface of his stoic appearance. The hind was light on her feet, well adapted to masking her youki, and was keeping downwind of him and his nose, but she could not escape his notice. At this point, he was determined to ignore her. She would falter eventually. All those that were not him always did with time.

However, he, for one of the rare few times in his life, had been mistaken.

The hind tracked him for days beyond their meeting. Days turned into weeks, then into months. She was intelligent enough to keep a fair amount of distance between them, but she dogged him as he patrolled what remained of his lands. She settled when he took up a temporary den, watched from on high when he hunted with hard, glassy eyes. He, in turn, was stubborn enough to pay her no heed. If she put this much effort into training instead of following him, she might have what she wished for, he mentally grumbled. The nights he could sense her slumbering aura in the surrounding wood, he contemplated slitting her throat in her sleep.

A dusty corner of the dog’s mind offered him a blithe metaphor of the hunter becoming the hunted, that their roles were reversed in this game. It was not true, of course, and he could have, at any point, stopped her foolish mission. Yet, he allowed it.

After all, it was not his time, nor his endurance being wasted.

When it had been fourteen turns of the moon’s cycle, he finally halted in the middle of his patrol. It was a quiet summer night, only cricket song broke the tense silence that it held. A breeze worried the long pampas grass in the field he’d chosen to at last confront his uninvited follower. Sesshoumaru drew in a soft breath of her scent, holding it before letting it go silently. He could hear the doe coming up behind him. She took no measures to conceal her presence this time. Even she seemed to understand that he was at the end of his very long patience with her.

“Doe,” he said without turning to face her. The wind carried the bass of his voice along with it, causing her to stop but a scant few meters away from where he stood. “What do you call yourself?”

“Tsubaki. I am Tsubaki.” He could not see her, but he was certain the weariness was beginning to make itself noticeable. Her voice was hoarse with disuse but stronger than he thought it would be. The steady wind ruffled the fur that clung to his shoulder. A lengthy pause proceeded his next thoughts.

“Tsubaki, you have told me you possess neither fangs or claws,” he addressed her. He caught the shift of her furisode against itself as she adjusted her stance.

“Yet, do you not possess hooves, nor antlers?”

“I do, my lord.” Her breathing grew errant. She was anticipating a fight, or perhaps something more.

“If you truly grieve enough for what you have lost that you desire power, I suggest you sharpen them instead.”

The night grew still around them, silence resuming its oppressive pall that was broken only by soft chirps of the insects hidden amongst the grass. At the edge of his hearing, the doe’s pounding heart settled like the previous breeze had died away. He allowed his eyes to close for a brief moment.

“Continue to give chase, and I shall kill you,” he turned his head to pin her with amber hues. Green stared back at them, and the Moonlit Prince noted that a different gleam took the place of the one he had seen when they’d first encountered each other; this one he could not place. His gaze returned forward.

He walked on.

This time, she didn’t follow.

#Affairs.#>OOC<#past plot#hey remember that time i wrote a vassal in for the sake of a rp and then accidently a character? me either ))

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

so @layzeal is hilarious and wonderful and this post gave me a chuckle and, because i think i'm funny, i added the following tags:

#oh god yes #and you just know that like 80% of the shidis and shimeis have massive crushes on their da-shixiong #so lwj would show up and be forced to reconcile this new unconscious and irrational desire to murder actual children #with his very conscious but still irrational refusal to examine why

and then the idea just sat in my head for months and now... well... i wrote this mostly today. it's not done. it's not edited. there are more parts, like, at least two more parts. but i figured i'd share this as it was and see if she liked it or not.

hope you all enjoy!

[T, 1.5k, 1/?, Wangxian]

--

Accepting this invitation was a mistake.

Lan Wangji had, in fact, been determined not to accept it.

But then Xichen had become involved.

Even Shufu was no help, having apparently decided that, while Wei Wuxian was an undisciplined boy, his siblings were well mannered enough and Jiang Fengmian was widely respected for the way he ran his sect. It would be good, Lan Wangji was told, for him to spend time outside of the Cloud Recesses with cultivators of like age and skill.

Wei Wuxian was, as Xiongzhang so helpfully pointed out, the only one of Lan Wangji’s peers to ever duel him to a draw.

As the comfortable serenity of meditation evades him for the third day in a row, Lan Wangji reflects with frustration on every step that led him here, to this lake, this pavilion, this unrest.

He circulates his qi through his meridians, carefully, precisely. He forces his attention to the flow of it, an exercise he teaches to his sect brothers and sisters who have only just begun to form their golden cores.

It is ineffective.

Stillness is fleeting at best. Thoughts slip into and around him, inevitable, insurmountable.

Lan Wangji would like to blame the heat -- he's never spent a summer in the southern plains -- the way the sun beats down and lingers. Even in the shaded protection of the pavilion, he can feel the overwhelming power of its rays. Oppressive and inescapable.

The air is thick with water. The breeze off the lake offers no relief.

He has, for the first time in his life, considered dressing in fewer than six layers. But fewer layers would likely lead to another problem, the source of which Lan Wangji refuses to examine. He's a teenager. Surely it's normal to--

Lan Wangji jerks his thoughts back to his meditation like a toddler who has never learned how to gently dismiss such mental interruptions. Basic, basic meditation practices. First principles.

Fuck. He feels so undisciplined. He hasn't struggled with his meditation this badly since he was six years old and his mother had just died and he couldn't understand what that meant. But that struggle was cold. Her absence had settled into his mind like fresh snowfall, crystalline flakes of guilt and fear that fell thick and heavy through the thin air of his calm.

This is similar, but not. This is heat: rays of the midday sun blinding him as they burn his skin. He feels like his blood is boiling inside his veins. His qi flares with yang -- bright, hot, fierce -- and his meditation fails him over and over.

He tries again.

Deep breaths. One at a time.

He counts out each inhale, each exhale.

He focuses on the expansion of his lungs, feels his stomach round itself to make room.

The exercise makes him feel silly, childish, but he is not above the basics. Clearly.

He is still counting, not yet centered when the thought returns: tanned skin, bare to the sun that turned it golden, shifts with the casual motions of an intermediate level sword form performed by someone who has long since mastered the style --

No.

Start again.

Lan Wangji releases tension where it’s built beneath his shoulders. Unclenches his jaw. Relaxes his hands.

Droplets of lake water trace the tendons of a slender neck, dripping from raven-black hair, still wet from swimming this morning --

Breathe.

Find the steady current of his body. The flow that settles within him.

The water is helpful in this: lotus flowers sway with an easy, vacillating rhythm. Back and forth. Gentle with the breeze.

He matches his heartbeat to it, the pulse of his golden core. Builds his breath from there.

He doesn’t allow himself to think about how long it’s been since he required external stimuli to regulate the patterns of his body. This is somehow easier than not thinking about other things. The erudite discipline of it is easier to reconcile within himself than the hot shame that flushes through him, following visions of sun and skin like the rush of the tide on the ocean beaches near his home.

Lan Wangji is unsure how much time passes like this -- which is worrisome by itself -- before he feels someone press against the range of his awareness.

Lan Wangji will admit that his range is… larger than most cultivators of his age. He’d chosen this pavilion on this pier because of its distance from the main house because, while normally it wouldn’t be a problem for him, with his focus as fractured as it is, he’d needed to find somewhere with the least amount of distractions possible.

Now, he waits to see if the person -- a woman, Jiang Yanli -- will come to him or if she is simply passing by.

She does neither, settling, instead, into a waiting position of her own, likely unaware that she has even been noticed. To be fair, by almost anyone else, she wouldn’t have been.

She sits with a kind of determined patience that anticipates but doesn’t begrudge a long wait. She would be perfectly unobtrusive if he couldn’t hear her every breath and feel the slow spin of her golden core.

Lan Wangji grits his teeth at yet another distraction and then forces himself to stop.

It is not her fault he cannot find stillness.

It is not even her brother’s.

This failure of Lan Wangji’s discipline is brought on by his own errors and he alone bears responsibility.

He gathers himself and rises. Stewing in his own frustration is no reason to neglect his host, patient as she may be. He feels worn and a little tender despite himself. Like sunburned skin rubbed raw with sand and salt and then covered with six layers of robes.

Yet he holds his sword and his posture smoothly. He moves with all the grace expected of him, Lan Wangji, a Jade of Lan and his brother’s heir.

Jiang Yanli’s smile, as she rises to meet him, betrays nothing but pleasantness. It reminds Lan Wangji of Xichen’s smiles when they are for other people: a perfect mask.

“Lan-er-gongzi,” she says, voice mild and sweet, easy to listen to, “how are you finding Yunmeng?”

He will not lie to her, but neither will he be rude. Despite his reputation, he is not cold enough to say, I find it loud and am more uncomfortable here than the last time I had to spend significant quantities of time with Nie Huaisang so that my brother and his could pretend to nighthunt together.

“Warmer than I am accustomed to,” he says instead, “but lovely to behold.”

“That is good to hear.” Something turns in her disposition. A wariness taking hold. She asks, “And the company?”

Lan Wangji isn’t sure what she means and he allows his confusion to show briefly between his eyebrows, “Jiang-guniang?”

Jiang Yanli seems to fold in on herself: shoulders setting themselves softer, chin dropping, eyes briefly lowering. Holding herself in deference, in contrition.

“If you find yourself the recipient of unwanted attention,” she places each word carefully, one after another, “please let me know and I will see that the attention stops and offer our apologies on behalf of Yunmeng Jiang.”

For a moment, Lan Wangji doesn’t understand what she could be referring to. And then he abruptly does understand. He has been secluding himself, meditating at the end of a pier for who knows how long and neglecting the very people he is here to learn from.

He feels himself flush as he works to gather the appropriate words and sees Jiang Yanli’s gaze flick to the side -- again, so much like Xichen -- to where he knows his ears are turning red with it. When her eyes return to his, her smile has changed. Not by much, and Lan Wangji is not as studied in reading the subtleties of her expressions as he is his brother’s. But, if their similarities continue, then the new brightness might mean something like Xiongzhang’s sharpness, and that never bodes well for Lan Wangji’s pride.

His posture stiffens, an involuntary reaction to brace himself for his brother’s ridicule, and he shakes his head politely, “That is not necessary, Jiang-guniang.”

He feels Jiang Yanli’s eyes on him again, which is strange because they never left him. It is a sensation he has only ever felt around Nie Huaisang before. Like being dissected, but kindly and from a distance. Not unlike his teachers evaluating any hint of deviation in his sword forms.

“Ah,” she says, and Lan Wangji wonders what she could possibly have seen on his supposedly unreadable face that might induce such a knowing sound.

He does not ask and she does not elaborate.

She sways lightly on her feet and catches herself against the railing as Lan Wangji reaches out to help her. She does not bat his hands away, but reaches out for him instead and says, “Lan-er-gongzi, I’m feeling a bit tired. Would you be so kind as to escort me to the practice field?”

Lan Wangji is not dense. He knows when he is being manipulated. But he isn’t sure why, exactly, Jiang Yanli wants him at the practice field, and he truly has no objection to bringing her there. So he nods.

“Of course, Jiang-guniang.”

da-shixiong wei wuxian…. can be so personal

him training the younger disciples….. helping the little ones mount their swords for the first time by holding both their hands…………. making them run little errands for him while he chews on a wheat stick ………giving a piggyback ride to one who twisted his ankle….. lightly scolding a shidi for practicing a dangerous sword form he wasn’t ready for yet but still patting his head with a smile so he doesn’t feel sad………

like. maybe it’s a good think lwj didn’t visit him in yunmeng, imagine if he saw that type of scene where the smart and witty troublemaker he fell in love with is also RESPONSIBLE and GOOD WITH KIDS. this was pre-sunshot guys. poor lan zhan would pass out on the spot

#how did this stupid little tag rant turn into something with /parts/?!#da-shixiong!wwx#repressed!lwj#lan wangji#jiang yanli#wei wuxian#wangxian#my writing#fanfiction#the untamed#cql#mdzs#summer in yunmeng au#this doesn't have a name yet so that's the tag we're sticking with for now#canon divergent au

775 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Nightmare Arc: III

Or: Walking Simulator 2017

Nothing.

That was what Illapa found, at first: nothing.

No light, no sound, no matter. Only the void, with its distant, vaporous clouds surrounding only empty space. As if propelled by some force other than his own, Illapa found himself pulled in one particular direction, away from the approaching clouds that had been dimly backlit. Not with the violet light one would expect from the realm of the shadow, but with an eerie, sickly red. And from within those clouds and that red came whispers, distorted beyond even the black tongue with which the Scion's kin might have spoken. Their language was maddened, mocking, relentless.

But so too was the relentless pull of that strange force, which carried him like a current in a stream, toward a pinpoint of light. It was a soft, blue light, but the contrast made it seem as though it might have been the brightest star at the heart of a galaxy.

Thwip.

Solid ground?

One foot stepped onto solid ground, unbidden. The texture was softer than one might expect from compacted dirt, cobblestone, or concrete, and as Illapa looked down, he discovered soft, blue-green grass. This... was Val'sharah, the land where the beauty of the Dream had been bespoiled by the Nightmare's corruption. This was the place between worlds, where the vigor of life still fought back against being twisted into misshapen beasts and unrecognizable piles of muck and slime.

Ahead, not too many steps down a path that glittered in places with what looked like garnets in with the gravel, was a bridge that could not have been possible. Over a stream of flowing emptiness that was of Elven architecture on both sides, but ten thousand years passed from one side of the bridge to the other. The simple Kaldorei woodwork gradually melded into a more elaborate contraption, the hand railings on the side gilded with vines of a familiar red and gold scheme. A single lantern illuminated the path beyond the bridge, beckoning with its eerily-inviting glow.

Illapa tread carefully now that he was moving of his own volition again. He was surprised to find the grass under his feet springy and healthy, and he placed his feet one after the other slowly and with care, almost reluctant to disturb the serenity of the grove by crushing those blades of blue-green grass.

Had the Nightmare not yet touched this part of the Dream? He thought back to the void of mist and light and strange radiations he had moved through just a moment before. He had not been pulled toward the churning cloud of crimson light and distorted voices, but to a single point of gentle blue-white light. He had seen that particular glow before, when Solarine's holy magic burned white-hot and transcendent.

She was close. Had the Scion guided him here, or had Solarine herself somehow drawn him in? Was this her dream? Or her nightmare?

He crouched at the edge of the gravel path, sinking long fingers into the lush grass. It felt vibrant, living, real as a meadow on a summer's day in Quel'thalas. He reached into the gravel and plucked one of the gleaming red gems from among the stones and held it up before his face.

The gleaming, garnet-like "gem" was something closer to a pomegranate seed, upon closer inspection. It held a squishy liquid encased in a thin membrane, but unlike a tasty pomegranate, this membrane did not contain anything edible. The "seed" inside turned, staring out at Illapa with a misshapen pupil as he inspected it.

The first signs of corruption, subtle and hidden in plain sight. The tiny gravel-sized eyeball reminded him uncannily of the Scion's array of crimson eyes as he gently rolled it between his fingertips. The eye within the membrane swiveled to keep its gaze on his face, its misshapen pupil expanding and contracting minutely to adjust to the light.

With a deft flick of his thin wrist, he tossed the tiny eye into the empty stream and rose to his feet, stepping onto the gravel path. The stones crunched quietly under the soles of his tall boots, punctuated occasionally by a tiny wet sound as one of the scattered eyeballs fell victim to his steps.

He crossed the impossible bridge, a small part of him marveling at the way the architecture spanned the ten-thousand year history of the elves, transforming gradually from the subtle, organic architecture of their most distant kaldorei ancestors to the ornate stylings of the magic-blessed high elves. The stream bed below the arch of the bridge was empty, and his steps echoed hollowly as he crossed into the light of the lantern at the bridge's other side.

The stream bed was not only empty, it was less than empty. Wisps of red-violet magics drifted into sight from time to time, out of the utter black void that seemed an endless chasm in what should have been a shallow stream. When the small red eye-seed fell into that stream of nothing, there was no plink of splashing water, but instead... the void whispered. Whatever it said was unintelligible, even to one fluent in the language of the void and the things that dwelt within.

Further down the path, there was a second lantern awaiting Illapa, its soft bluish light brightening the haze of humidity that hung as a pall over the green of the grass and towering forest.

As the impossible bridge gave way once more to the gravel path, the landscape changed. The green forest of Val'sharah evolved before all eyes present, ten thousand years of evolution happening in only a couple of footsteps. The tall oaks and larches and maples and firs twisted and changed, forming themselves first into familiar golden oaks and swirling cypress; and then, the gold began to wither and fade into sickly, dull green. The beautiful, blue-green grass kept its hue, but it began to wilt, and large, glowing mushrooms began to sprout alongside the path.

This was a familiar sight to any Sin'dorei, but instead of the spiderwebs that clung to the warped and twisted trees and plants in the waking world, there were strands of red slime. Hair-thin, almost like spiderwebs, but instead of spiders, there were tiny, digusting eyeballs with eight or nine spindly legs sticking out haphazardly. These eyeball-spiders appeared to be the only thing approximating animal life as the landscape of the Ghostlands made itself known, but from the mists arose something that told Illapa and the Scion that there was something there other than monsters.

Far off, in the distance, was the sound of wailing. A few voices rose above the oppressive silence, echoing through the trees. It was a sound any soldier would know, the sound of mourning after a losing battle.

It was a sound with which Illapa was terribly familiar. He was not a soldier of rank and file, but he was nonetheless a man of war, whether he was the brilliant beacon standing with the armed forces or the dark-robed shadow walking among the fallen at the battle's end -- giving healing to those who could be saved, swift mercy to those who could not, and the Sunwell's final blessing to those who were already beyond.

It had been some time since he had last acted that role -- a few years, at least -- but at the first sound of echoing grief, he felt his stance shift unconsciously, already taking on the solemn mantle of his priesthood. He took the next lantern from its roadside post and carried it with him, a gentle blue light in the dark gloom of the Ghostlands.

The distant, echoing wails continued as Illapa walked along the lamp-lit path. Just when it seemed they might have subsided, another low moan would float through the air, carried upon the strange mist like the feather of a dying bird.

Soon, a signpost emerged from a fork in the path, its base enveloped in red slime mold. They wended their way up, with and through the wood, and the letters reading Tranquillien glowed from within with that same red light. A sane man might have avoided a path so blatantly pointing toward the heart of Solarine's nightmare and that corruption that lay within, but then a sane man wouldn't have stepped through with an eldritch monster in the first place.

Further down the path, another dim blue-white lamp lit the way, its glow somehow warm and inviting even in the creepy gloom of the Ghostlands.

He was sane enough to feel like a man following a will o' wisp into the swamp, chasing that inviting glow straight into a bottomless peat bog that would suck on his bones for centuries until someone dug him up to distill a batch of scotch.

Still, at least he knew exactly how treacherous was the path he walked. The lantern he carried created a circle of gentle light that moved with him as he turned at the tainted sign to follow the lighted path. Even if they led him toward doom, he had no other path to walk -- literally or figuratively.

Illapa was not the only being that might sense the strange "call" that came from the direction of Tranquillien, as soon as he stepped foot beyond the fork in the path. It lasted only moments, that strange and almost hypnotic whisper... like a song, but inside the mind. A siren's call, if they were lucky.

The Nightmare's horrid, bloody-red glow littered the sides of the path leading toward Tranquillien, twisted roots jutting up from puddles of muck, red strands of slime webbed between the rails of the fencing that sporadically appeared alongside the path.

Then, just as it seemed the corruption would overtake everything and consume whatever was left of Solarine's dreamscape, the Nightmare ceased. The red haze vanished from the air, the sticky slime become nothing more than cobwebs, and the mushrooms were just mushrooms. A single, glowing feather laid in the center of the path, right at the line where the Nightmare had been stopped in its tracks. Beyond the feather was the ruined town of Tranquillien, miraculously free of any corruption beyond that of the undeath which had claimed the land a decade before.

The Nightmare deceives. The Nightmare devours. The Scion's warning resonated in his memory as he stood at the line where corruption gave way to familiarity. The glowing feather rested serenely at the toes of his boots, and once again he crouched to consider the strange tableau which presented itself.

The siren song whispered in his thoughts, just a few entreating strains, but it gave him pause. Something wanted him there. Something was luring him there. "Do you hear that?" he said quietly, as if to himself, but something else answered from nearby.

"Yes," the Scion said, stepping out of seemingly nowhere, as it often did. Illapa gave it a faintly reproachful look, and it spread its hands diffidently. "We have been resisting the borders of the greater Nightmare that encroach on this part of the Dream. You asked for time, Our Eyes; We have given you what We can."

Illapa spared it no gratitude. "Do you recognize it?" he asked. The monster tilted its head as though listening to a strain of music from an adjoining room.

"It is a unique voice," it answered. Illapa nodded and plucked the glowing feather from where it rested at his feet. Another sign of Solarine's magic: he had seen her mantled by feathered wings when she pulled a departing soul back from the brink of death.

So it was unique, that siren's call, with its strangely tranquil and calming quality. The promise of peace and relief from the haggard, destroyed landscape and the corruption that boiled within.

Beyond the feather, past the apparent barrier which had halted the spread of the Nightmare, nothing but death greeted them. Corpses littered the path leading into the center of the town, but these were neither fresh nor those of living beings. These, half burnt into ash and charcoal, were corpses that had once been dead and rotting in the ground, and which had now been returned to doing just that. It was a massacre of undead, brutally efficient handiwork of which the Scion itself might be proud.

However, Solarine herself was nowhere to be found.

A new lamp flickered to life, calling them into the town that lay beyond.

Another familiar scene -- it could have been taken from many of his more mundane nightmares. This more than anything assured him that Solarine would be close; these were nightmares he knew that she shared. It cast his surroundings in a new, intensely personal light compared to the crimson-infested landscape behind him. The ground he tread now was her own personal nightmare, as much memory as dream.

He stepped between the piles of Light-blasted bones and carbon remains, leaving footprints in a layer of ash. The song, part hymn and part lament, beckoned him on, and his heart was leaden in his chest as he began to suspect its source.

There was nothing else in this blighted dreamscape that could be so haunting and so beautiful.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Vernacular on the ground in Madhubani

I needed to come back to the blog on the occasion of the International Delhi Art Fair in New Delhi that took place Feb 2 - Feb 5, 2017. Unfortunately I was unable to attend the event and so missed the exhibition of Vernacular art curated by art historian Annapurna Garimella which included Gond, Mithila and Mysore artists. Though space was limited, the exhibition offered much needed exposure for India’s indigenous art forms.

Here I would like to present six artists whose work I think truly shows what is happening on the ground in Mithila art: the excitement of experimentation and the search for a personal artistic path in the face of social and technological changes.

Avinash Karn ‘Munna, Smile Please’, 36″x24″, acrylic on canvas, 2016.

Avinash Karn studied art at Banaras Hindu University and then spent the last couple of years sowing the seeds of Mihtila art in India: painting Mithila-style hotel murals in Gurgoan, teaching the basics of the art to tribals in Jharkhand, holding Mithila workshops in Goa. In this piece he photo-shopped a traditional photographer’s studio backdrop onto canvas and then painted the portraits in the areas left blank. Combining traditional photography practice with current day digital manipulation and finishing with a painted portrait in the Mithila style not only gives an engaging picture of a middle-class family in today’s India but also presents the options, choices and tools Mithila artists have at their disposal today.

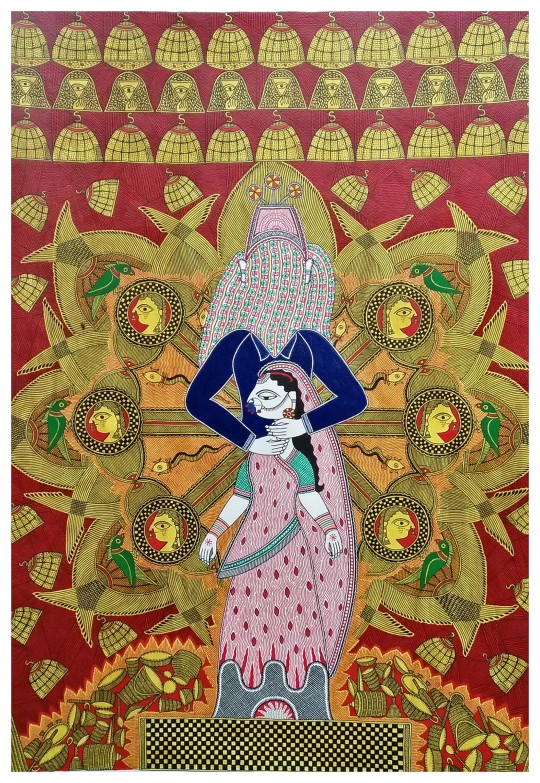

Mahalaxmi and Shantanu Das, ‘Kohbar Monologues No 2′ , 22″x30″, acrylic on paper, 2016.

A chilling piece of theater. The husband in traditional bridegroom headdress chokes his wife as flames reach up her sari from the household cooking fire. The rich, thick, blood red color adds a quiet horror to the scene while the lotus pond wedding kohbar is deconstructed here as a wheel of torture, the lotus flowers the tearful faces of brides. Bamboo representing the male lineage becomes scythes that surround and further entrap the unfortunate young wife. On high, old women peer through their saris at a scene they are helpless to prevent.

The traditional kohbar symbols painted on the walls of the wedding chamber represent the hope of a fruitful and happy marriage. Here they become instruments of oppression and death. A powerful painting dealing with a reality that manifests itself in various guises in contemporary Indian society. Though this artist team had a large canvas work in the exhibition in Delhi, this painting is extraordinary and a must in any exhibition of contemporary Mithila art.

Shalinee Kumari . At age 23, via the Mithia Art Institute in Madhubani, Shalinee Kumari made the journey from the small village of Baxi Tola near the Nepal border to San Francisco for her one woman show. After a two week stay in the States she returned to India, married, and now lives in Hyderabad with her husband and daughter where she teaches and continues to paint.

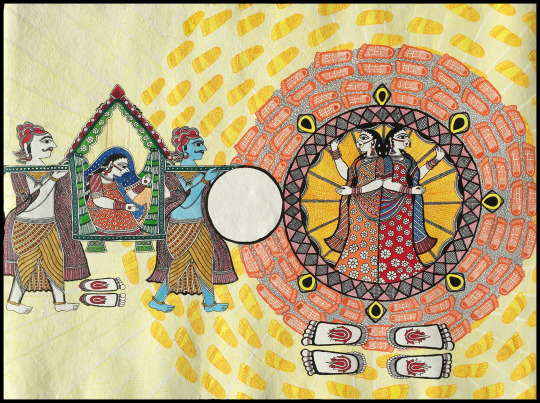

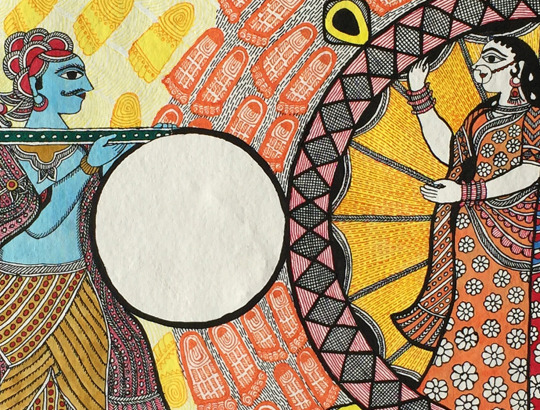

Betiyaan Parayi Hoti Hai (Daughters Are for Others), 30″x22″, acrylic on paper, 2016.

The bride carried to the husband’s home loses not only her birth family but also has no rights in her husband’s family. This is the patriarchal tradition. Shalinee Kumari is not the first to ask why this must be so, as songs on You Tube attest, but she is the first Mithila artist to so elegantly limn this tradition. The footprints go in circles, in both directions. They point back to the old family and forward to the new. They search for an answer. And as in the songs there is no answer. At least not yet.

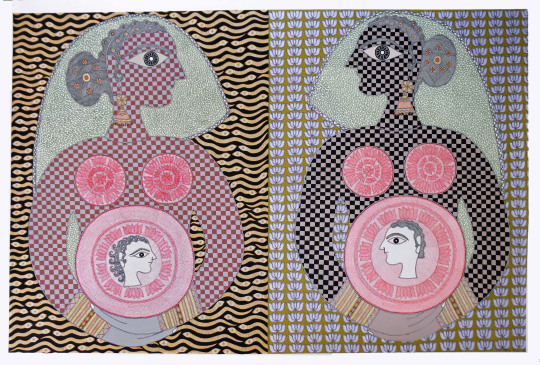

Amrita Jha is an accomplished artist and a Mithila Art Institute graduate. Though currently at work on a series of bird paintings much of her art is informed by the problems of being a woman in a highly patriarchal society. Here her The Curses Begin, 40″x33″, acrylic on paper, 2016.

“Usually, a mother-in-law starts to curse the day she knows that her daughter-in-law is carrying a girl child in her womb and becomes extremely happy if she is carrying a male child.” Amrita Jha

Unmatched in her attention to line,color and detail, Amrita Jha here gives us a stylized, formal portrait of two beautiful young women, facing each other, nearly identical mirror images except for the background behind each: one a wall of light purple lotus flowers while the other a field of undulating golden snakes. The gems in their perfectly coiffed hair, their golden earrings, the multiple colored bracelets on both wrists and their shimmering saris give them a somewhat haughty air which is softened by their clasped hands tenderly supporting their yet to be born son and daughter. Both mothers, both awaiting the birth of their child.

But note how, reflecting popular sentiment, the artist’s choice of the vertical gives the boy child’s mother a height and authority denied to the mother holding the daughter. The vertical rows of lotus flowers continue up to the heavens while the horizontal lines of snakes create a visual field that surrounds and entraps this mother and her future daughter. The sex of the child also reflects back onto the mother where the darker, contrasting colors of the figure cradling the boy give that figure, a presence, a self assurance that is lacking in the mother-daughter figure with its slightly anemic colors.

The Curses Begin is a well conceived and well crafted piece exhibiting the best of traditional Mithila Kachni Bharni (line and color) painting .

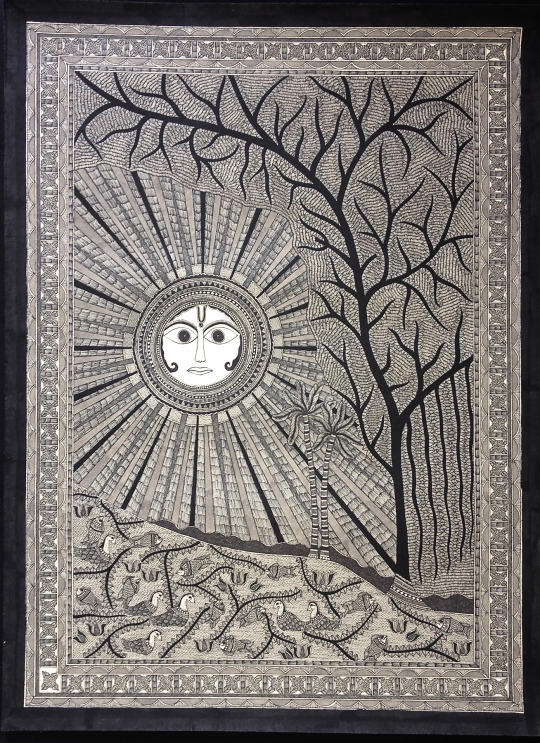

Naresh Kumar Paswan: To complete my selection of current Mithila Vernacular painters I must also include Naresh Kumar Paswan. He is a unique, self-taught talent whose work resembles no other. All in black pen and ink with geometric lines that make his work seem a handcrafted woodcut, he paints scenes from Indian stories as well as nature. If Surya the sun God appears a bit fierce in this piece, that is deliberate. Naresh says that in the middle of the Indian summer, out in the villages, the sun is anything but your friend.

Sun and Pond 22″x30″, acrylic on paper, 2014.

I suggest that these are some of the most interesting artists working in Mithila art today. Some already accomplished but still relatively unknown, while others are just ‘emerging’ as the galleries say. For now the Vernacular in Mithila/Madhubani art lies with them.

5 notes

·

View notes