#Implicit Bias

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I love Mel and I'm glad so many people agree on her beauty, she is a gorgeous, breathtakingly majestic black woman and I'm glad she's appreciated but istg mfs only ever talking about how attractive she is rather than her intelligence and complex morality.

Everyone wants a morally grey woman character until she's black suddenly it's crickets in the crowd. Ik it's not usually intentional but (typically white) people have such an inate unwillingness to discuss poc (Especially woc) characters beyond surface level and it's annoying asf

#implicit bias#or whatever#im black tag#do i main tag this... usually idgaf but like i dont rlly fw the arcane fandom and fear in liable to get jumped 💀#white fandom#arcane#grahah doing it anyway bc i want organization on my blog please good white liberals do not attack me..#moth.txt#mel medarda

364 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just think we should start framing these things in the first person. I am not immune to propaganda. I have implicit biases, in spite of my explicit beliefs, which I need to keep in check.

#guiltyedits#you are not immune to propaganda#garfield#I have a bunch of stray reasons for this argument but they're not coherent right now <3 I'm sure nobody's DYING trying to figure it out lmao#implicit bias#internalized#affirmations#self-regulation#leftist

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

Usopp’s identity

I understand that some people disagree with the idea that Usopp is Black, and everyone is entitled to their opinion. However, I do believe there are those in the fandom who go out of their way to deny Usopp’s Black identity as a way to mask their unconscious bias. We all have biases to some extent—that’s inevitable. But to refer to people who argue for Usopp’s representation as a 'crying minority' is both insensitive and dismissive. It’s baffling how some can be so blunt and careless about race and stereotypes online, yet act differently in public. Now that Usopp’s skin tone seems to be getting lighter, the debate has become even more heated.

#one piece#usopp#op usopp#one piece usopp#god usopp#usopp one piece#sniper king usopp#straw hat usopp#sniper king#captain usopp#black anime#one piece manga#one piece anime#wesleysniperking#black identity#prejudice#implicit bias#bias#poc

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

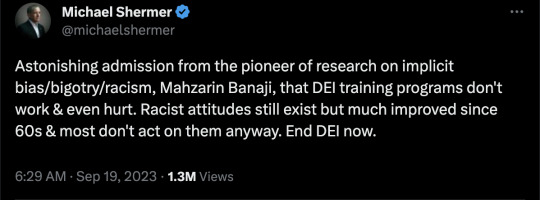

Read More Here: Substack

#algorithmic determinism#techcore#philosophy#quote#quotes#ethics#technology#sociology#writers on tumblr#artificial intelligence#duty of care#discrimination#implicit bias#law enforcement#psychologically#computational design#programming#impact

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

CinemaTherapy, Tone Policing, Mace Windu

The CinemaTherapy video on Palpatine contains, I will say it nicely, opinions about the Jedi in general that I disagree with, (I love most of their videos, and their advice on avoiding manipulation in this one is useful and good, I hope it helps people, etcetera) but what I want to talk about is the specific moment where they mention Mace Windu for literally half a second.

At 14:07-14:29, they say, (copying directly from the episode transcript):

Jono: But what Anakin is not mature enough or mindful enough or experienced enough to be aware of, is that he's being steered right, and that Palpatine is doing it deliberately to drive a wedge between Anakin and the people he cares about and who care about him. At least a few of them do. Um, not Mace. Mace. Come on...

Anakin [ROTS clip]: I must go, Master.

Mace [ROTS clip]: No.

Alan: Do better, man.

Jono: Do better, Mace.

I firmly don’t know what explanation there is for this other than tone policing of a black man. Whether it’s CinemaTherapy’s problem specifically, or if they’ve just been drinking the fandom koolaid I don’t know, but it’s a problem either way. Let me explain.

The casualness of the remarks is wild. There is a full eyeroll, and several *theatrically* shaken heads. The transcript does not fully convey how out of place it feels watching it. It's almost to the point where I really want to give the benefit of the doubt and believe it's sarcasm, but the rest of the video does really not support that assumption. (If this is my failure of interpreting other humans, and it was sarcasm, then forgive me, I suppose).

I’m not even sure what aspect of Mace's behavior toward Anakin they’re addressing? The ROTS clip they choose to play of him—presumably an attempt to highlight whatever they’re talking about—is from Mace telling Anakin to stay behind when he's going to face Palpatine.

Of all the moments, if I was ever going to try and construct a “Mace is mean to Anakin specifically narrative,” I would not pick that one? It’s quite literally the chillest interaction they have in all three movies? If I was them, and trying to actually showcase an “Anakin’s doesn’t get enough affirmation or connection from the Jedi,” narrative, I would choose a scene like when Mace says Anakin won’t be trained. At least there you could make a argument that the council’s decision could’ve been explained a bit less bluntly, and that there’s something of a “conversations that adults should be having privately are instead occurring in front of a child” situation.

The casualness of the remark, the “Do better, Mace” and the knowing head shakes, those matter. The way they’re just tossed in, as if every audience member will instantly agree and chuckle at how of course Mace Windu is being mean and rude, they tell the casual Star Wars viewer that this is a universally accepted position, when it is not.

It also supposes the idea that Mace owes Anakin special emotional labor. A relationship therapist might, I don’t know, consider the relationship between Anakin, Mace, and the very relevant context of the interaction before making this judgement? Mace is not one of Anakin’s friends, confidants, or even a member of his lineage. He is, especially in the moment they chose to highlight, the leader of the Jedi Order. Anakin’s boss, to oversimplify, and the leader of Anakin’s people, to say the truth. He’s worried about the fate of the entire galaxy at that specific moment!

And guess what? He’s not even being rude, at all. He’s being direct, that’s it.

If they had chosen to highlight the line, "If what you have told me is true, you will have gained my trust," and talked about Mace not trusting Anakin, I might have been willing to humor this argument out of respect for the relevant textual evidence and for the sake of having some peace. But no, in their own words, this is about, "Anakin and the people he cares about and who care about him." This remark is about care, not trust.

And guess what again? Despite all of the other things he has to think about, Mace is considering Anakin’s feelings here. He isn’t telling Anakin to stay behind because he doesn’t want Anakin to be allowed to participate is the cool fun lethal lightsaber duel. He does it because Anakin is emotionally compromised. Even if you think of the the Jedi as flawed, you cannot think taking Anakin to fight Sidious would be a good, safe, or healthy idea? Would you take the person who you’re just figuring out has probably been groomed for years into a violent confrontation with their abuser?

Mace Windu is doing everything, thinking of everything, and caring about everything in this scene, and yet fans still find fault with him. They still find him insufficient and mean.

Opinions like these are not subtle, they are not cute, and they are deeply influenced by what Mace looks like in relationship to what to what Anakin looks like.

Step back, examine scenes for what actually occurs in them, rather than what larger fandom and larger society tells you is happening in them. This is the core of analyzing and creating art. What do you see in the world that others do not? I beg of you, see Mace Windu for once.

(If I was going harder, I would talk about how I think their very lame opinions of the Jedi are causing them to actually miss some of the depth of Sidious’ manipulation (including leaving out so much as a mention of the scene where Obi-Wan very explicitly tells Anakin he’s proud of him), but again, for the interpretation they’ve decided on their advice seems good, so I’ll leave it alone.)

#cinema therapy#star wars#jedi#mace windu#anakin skywalker#sheev palpatine#darth sidious#tone policing#implicit bias#racisim#krayt complains

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Jake Mackey

Published: Aug 2023

“Live not by lies.” —Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

A “virtuous lie” is a false, misleading, or highly contestable claim that is promulgated without qualification as flatly true in order to serve a purportedly emancipatory end, despite the fact that evidence of its falsehood, deceptiveness, or contestability is readily available. We live by these lies. They underlie a great many communications in the media, in academic journals, in government, and at elite educational institutions like my college.

For example, a recent announcement for a talk read: “In this lecture, [the guest] asks, what can we do about unkindness? How can [we] grapple with this messy, borderless concept, which has influenced so much of our post-1492 era?” The announcement does not so much assert as simply presuppose, and ask readers to accept, that “unkindness” is a distinctive characteristic of the post-Columbian world. Readers are invited to draw the inference that “unkindness” had less “influence” in the world before Europeans arrived in the Americas. Like much of the messaging on elite campuses, this one implies that the West in general and perhaps the United States in particular are uniquely culpable in history’s evils.

Another example: I attended a talk by a prominent author, a journalist, at a super-elite private high school. He took pains to paint North American slavery in the most gruesome of colors, as well one might for the edification of young people, who are inevitably ignorant of its true toll. In so doing, however, he told two virtuous lies: first, that slave-farmed cotton drove the expansion of the antebellum U.S. economy and, second, that increases in cotton productivity resulted from increases in the torture of enslaved people.

These two claims, both of which come straight out of the “New History of Capitalism” and, via Matthew Desmond’s contribution, are central to the 1619 Project, have been debunked.1 And yet these lies are virtuous. North American slavery was a moral abyss. One can never overstate its horror or overdo one’s condemnation of it . . . even if one lies. The lies of the “New History of Capitalism” are virtuous, serving purportedly noble goals, such as reparations, as the speaker took care to make explicit in his talk.

A third example: on May 21, 2020, as if to foreshadow the murder of George Floyd that was to come four days later, Kimberlé Crenshaw, a professor of law at both UCLA and Columbia and coiner of the concept of intersectionality, wrote in the New Republic that anti-black police and vigilante violence represented “modern embodiments of racial terror dating back to . . . the reign of white impunity rooted in slavery and Jim Crow” and opined that such violence was part of a pattern that amounts to “a kind of genocide.”2 In a similar vein, star attorney Ben Crump titled his 2019 book Open Season: Legalized Genocide of Colored People. Chapter two is titled “Police Don’t Shoot White Men in the Back.” Note that this was the tone of the discourse before George Floyd.

What we see in this catastrophizing rhetoric about genocide is the product of the virtuous lie that black people, and black men in particular, are being murdered by racist police with wild abandon. As Derecka Purnell put it in the Guardian: “We know how we die—the police.”3 This perception is the result of a virtuous lie. The lie promotes a distorted view of reality. It is a well-meaning distortion but a distortion nonetheless, designed to bring attention to the cause, worthy in itself, of police brutality against black people.

The reality, of course, easily accessible to all online, is that while there are indeed disturbing anti-black disparities in the police use of nonlethal force,4 there do not appear to be racial differences in the way police deploy lethal force. In other words, police are, overall, no more disposed to kill a black person than a white person. This basic finding has been discovered and rediscovered again,5 and again,6 and again,7 and again,8 and again,9 and again,10 and again.11 And yet so taboo is this finding, and so sacred is the lie, that people have been fired for noting the former in order to correct the latter. Such was the fate of Zac Kriegman, a director of data science at the news and information company Thomson Reuters. When he pointed out that Black Lives Matter, whatever the organization’s salutary contributions to our political life, was promoting a virtuous lie,12 he was fired.13

Indeed, Kriegman was not the only casualty of the virtuous lie that lethal police violence specifically targets black people. In 2019, a paper was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) that found “no evidence of anti-Black or anti-Hispanic disparities across shootings.”14 Due to an unusual set of circumstances, including a congressional hearing about policing, the article quickly became a flashpoint. First, it was officially “corrected,” though its findings were not altered. A few weeks later, George Floyd was murdered. Soon after, as the article began to be cited and contested in the ensuing debate about policing, PNAS asked two independent researchers to look into the article’s data and methods. They found that the article “does not contain fabricated data or serious statistical errors warranting a retraction.” Nevertheless, the article’s authors themselves retracted it, citing as their reason “continued use of our work in the public debate” about policing. PNAS chimed in, too, saying that “partisan political use” of the article warranted retraction.15 The virtuous lie and the political program it serves must be protected at all costs.

Virtuous lies are not confined to high schools, colleges, major media companies, and scholarly journals. Our government and medical establishment increasingly run on virtuous lies as well. For example, in 2019, California passed a bill, AB 241, that requires “implicit bias” training as part of routine continuing education for physicians, nurses, and physician assistants.16 The bill asserts the following: “Implicit bias, meaning the attitudes or internalized stereotypes that affect our perceptions, actions, and decisions in an unconscious manner, exists, and often contributes to unequal treatment of people based on race, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, age, disability, and other characteristics.” And in case you missed the causal chain running from implicit bias through behavior to health outcomes: “Implicit bias contributes to health disparities by affecting the behavior of physicians and surgeons, nurses, physician assistants, and other healing arts licensees.”

AB 241 is wholly based on a string of interconnected virtuous lies about implicit bias. The first virtuous lie is that researchers have settled on a coherent and consistent understanding of what the term “implicit bias” means.17 The second lie is that whatever implicit bias may be, we know that it influences behavior.18 The third falsehood is that we know that disparities in health outcomes are caused by the behavior of implicitly biased medical personnel.

The truth about implicit bias is easy to state: “[I]t is not clear precisely what is being measured on implicit attitude tests; implicit attitudes do not effectively predict actual discriminatory behavior.”19 Moreover, with respect to disparate racial outcomes, it is important to note that measures that attempt to use implicit bias “to predict behavior find little or no anti-Black discrimination specifically.”20 This is good news! It means that racial health disparities are likely not wholly or even significantly attributable to the implicit bias of medical personnel.

What discrimination there is in medicine—and there surely has been and is discrimination—is based on entirely explicit attitudes supported by pseudoscientific theories. For example, it used to be a common practice among medical laboratories to adjust the renal values of black patients to take into account black people’s supposedly greater muscle mass relative to white people.21 Such adjustments might, however, have caused doctors to overlook kidney failure in black patients. Again, some white physicians are said to believe that black patients are less susceptible to pain than white patients because, the theory goes, they have longer nerve endings and thicker skin.22 These are not “implicit biases.” These are wholly conscious false beliefs that can be dispelled by acquaintance with the truth.

Nevertheless, California’s medical personnel now must pay the opportunity cost of submitting to training for implicit biases, training that we know to be useless. In a sense, the mandating of implicit bias training is a fourth virtuous lie, for the fact is, “most interventions to attempt to change implicit attitudes are ineffective.”23 What we have, then, is an entire government-mandated regime of healthcare education built atop the foundational virtuous lie of implicit bias.24 Articles appear regularly to bolster the lie in journals that could once be trusted. If everything you knew about implicit bias in medicine came from the latest article about it in Science,25 for example, you’d know very little indeed.26

We live by lies like implicit bias because we suppose that doing so makes us good people. To question them is to align oneself with all that is oppressive. Our moral credentials are burnished if we condemn European contact with the Americas as the moment at which “unkindness” became a force in human affairs. We signal our ethical seriousness with respect to American slavery and continuing black socioeconomic inequality if we applaud rather than quibble when debunked theories are presented as plain facts to high school students. We stand ostentatiously on “the right side of history” if we endorse BLM’s narrative that black people are “intentionally targeted for demise” by police.27 Similarly, medical personnel in California now attest their racial innocence by submitting, ironically enough, to the proposition that their implicit bias is causing them to mistreat racial minorities and to a highly profitable training industry that purports to remedy it.

As in the case of the narrative about police killings, to question any of the claims built upon the virtuous lie of implicit bias is to court personal and professional disaster. Edward Livingston, then a deputy editor at the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), discovered this in early 2021 when he went on a JAMA podcast and made the mistake of suggesting that accusing doctors of racism was perhaps not the best way to resolve inequities in health outcomes and that the solution might instead lie in addressing socioeconomic disparities.28 This marked him for destruction. A petition against JAMA garnered nine thousand signatures, the podcast episode was scrubbed from the web,29 an investigation was announced, he was asked to resign his editorship, which he did,30 and he was made the subject of a “restorative justice session” at UCLA medical school, where he teaches.31 Yet the spread of the miasma was not stopped by these expiations. JAMA’s editor-in-chief, Howard Bauchner, who had had nothing to do with the ill-fated podcast episode, fell over himself apologizing for the incident but was investigated by an AMA committee and soon had to resign his editorship.32

The fates of Kriegman, Livingston, and Bauchner, as well as my own reticence to push back on the high school speaker, reveal a central feature of the logic of the virtuous lie: to correct these lies is tantamount to opposing noble goals. Nobody wants to be the one who points out that a virtuous lie is not true. In the case of the high school speaker, any pushback would have come across as a defense of American slavery. In the case of “our post-1492 era,” to ask for evidence would be to minimize the enormity of the post-Columbian devastation of Native Americans and of the transatlantic slave trade, just for starters. Regarding claims of a state-sanctioned genocide of black people, to gesture toward research to the contrary would be to affirm the status quo and to oppose much-needed reforms.

The Epistemology of the Virtuous Lie

Let us distinguish the virtuous lie from two adjacent phenomena—Plato’s “noble lie” and Rob Henderson’s “luxury belief”—and then consider the choice of the term “lie.”

The noble lie. Plato introduces the noble lie in Book 3 of his Republic. Socrates, the lead character in the dialogue, urges that in order to found his proposed ideal city, they would need to craft “one noble lie which may deceive” the city’s three social classes, that is, the ruler class, the soldier class, and the producer class:

“Citizens,” we shall say to them in our tale, “you are brothers, yet god has framed you differently. Some of you have the power of command, and in the composition of these he has mingled gold, wherefore also they have the greatest honor; others he has made of silver, to be auxiliaries; others again who are to be husbandmen and craftsmen he has composed of brass and iron.”

The point of Plato’s noble lie is to reconcile people to inequality and their place in the social hierarchy, in order to create the ideal city, with a place for everyone and everyone in their place. The mechanism of reconciliation is a naturalization of the hierarchy not by analogy or comparison to metals but through the assertion that people of differing stations are quite literally made of different metals. The rulers are golden, the soldiers silver, and the workers brass and iron.

Luxury beliefs. Rob Henderson defines luxury beliefs as follows: “Luxury beliefs are ideas and opinions that confer status on the upper class, while often inflicting costs on the lower classes.”33 People crave status symbols and signs of distinction. Some such signs are expensive clothing or tastes that can only be cultivated by those with surplus time and material resources. Beliefs can function as another status symbol, however. Henderson uses the example of “defund the police,” which is endorsed disproportionately by those of high socioeconomic status, who, as a result of living in places relatively invulnerable to crime, would suffer the least from defunding. This belief is a luxury for them. It has no material impact on them, but it signals their high status to their peers, who are equally safe from crime. Yet this belief is often unaffordable for poorer people, who tend to live in places that make them vulnerable to crime. “Defund” is a luxury beyond their means. If the elites, who dominate the media discourse and exert control in government, get their way and succeed in defunding the police, the costs of the policy will be borne disproportionately by the poor.

Virtuous lies versus noble lies and luxury beliefs. Virtuous lies differ from both Plato’s noble lies and Henderson’s luxury beliefs. Plato’s noble lie promotes acceptance of an inequitable social order, depicting it as natural, inevitable, and just. In contrast, the virtuous lie invariably produces dissatisfaction with the social order, which it depicts as illegitimate or unjust. The noble lie reconciles us to social inequality whereas the virtuous lie is intended to serve a project of dismantling inequality. Finally, the noble lie is ultimately metaphysical. That is, it purports to offer an account of the underlying nature of reality that can be adduced to explain social arrangements. The virtuous lie, in contrast, is concerned with the social arrangements themselves in their historical, sociological, economic, and psychological dimensions, as the examples above show.

Virtuous lies share with luxury beliefs both a commitment to emancipatory political programs and a concern to signal moral goodness. As Henderson’s example of “defund” suggests, however, luxury beliefs are inherently normative. They depict a prescribed course of action. Virtuous lies, in contrast, are purely descriptive. They purport to represent states of affairs as they exist in the world, for example, “police hunt and kill black people,”34 or “Black lives are systematically and intentionally targeted for demise.”35 Virtuous lies like these provide the “factual” basis for normative luxury beliefs like “defund the police.”

Why call virtuous lies “lies”? A lie is, by definition, a false claim that is asserted despite its known falsity. A lie involves intent to deceive. I would not pretend to know that everyone who utters what I have called a virtuous lie knows that it is false (or at least highly questionable) and intends to deceive. Surely some do, but I imagine that many or even most who repeat virtuous lies do so sincerely, because they know no better.

Why might so many know no better? The term “lie” seems especially fitting here. Unlike the unwitting laypeople who repeat them, those who invent and promulgate these untruths, including activists, media companies, and law professors, are in a good position to know better and have an epistemic obligation to the truth that should give them pause.

There is something gratuitous about virtuous lies, not only when they are uttered cynically by knowledge-economy elites but even when they are uttered unwittingly and sincerely. Respected professors of law who specialize in racial issues and major media companies whose own data scientists have alerted them to the truth have no excuse. But neither do laypeople, really. The information that problematizes or even debunks virtuous lies is not kept locked away. Anyone who even halfway cares about what the world was like before 1492, whether slavery was central to the economic surge of the early United States, whether there is an epidemic of racist cops murdering black people, or whether implicit bias is a well-defined construct that has a clear effect on behavior can find the truth with the click of a mouse, or at least a vigorous debate, that should cause one to back off of strong claims.

Those given to whataboutery will have been champing at the bit to utter one word in response to my theory: Trump. The man is, after all, a liar of world-historic proportions. One of his most vicious lies is that the 2020 election was stolen. Indeed, according to a recent CNN poll, 63 percent of Republicans still believe that Biden “did not legitimately win enough votes to win the presidency.”36 But Trumpian lies, and right-wing lies more generally, are manifestly not “virtuous” insofar as they are outwardly self-serving, even if the teller believes in the ultimate truth of the cause. They make no pretense of serving an emancipatory project. They serve a project of acquiring political power and they do so nakedly. In a sense, this nakedness is refreshing. After all, virtuous lies, too, are promulgated in pursuit of political power, but under cover of the pretense of fighting it.

Vicious Consequences of Virtuous Lies

Why not just embrace the most emancipatory virtuous lies? After all, they promise to inspire the activism and political will needed to address some of our most urgent problems. The answer is that virtuous lies offer only a false promise. Let me say why.

First, the internet has put any citizen with even a modicum of curiosity and a free Sunday afternoon in a position to adjudicate these claims for herself. We are in an era in which you simply cannot keep information from people anymore, and you cannot lie to them.

Second, the lies will alienate at least as many people as they inspire. The virtuous lie is not a reliable formula for any political change apart from greater polarization. In other words, a commitment to these lies on the part of the media and our knowledge-producing class more broadly means that there will always be a number of Americans who embrace the lies out of ignorance or tribal loyalty. There will also, however, be a growing number of Americans who, as I have already suggested, will figure out that they are being lied to. This will create, or is already creating, a division in which a side consisting of tribally committed virtuous liars faces off against a side consisting of people who resent being lied to. This division is and will be toxic to our politics and hence to our democracy. It will only promote the rise of more Trump-like figures, who feed on and exacerbate the resentment of voters who dislike being lied to.

Let’s take just one of the virtuous lies discussed above, the lie about racist murders by police, and follow it through. Some might say, sure, perhaps it is not quite true that the police go out hunting for black people. But this fib is innocent because it has beneficial effects. The proof is right before us: after all, it has spurred a massive nationwide and even worldwide movement for change. What could be bad about such a lie?

I would answer that the lie is not worth it. The cost of the lie is paid as a psychological toll on all Americans, but on black Americans especially: the needless psychological suffering that results from hearing that you are being “hunted” by agents of the state in your own country. As Musa al-Gharbi put it in these pages, speaking of such narratives more broadly:

For people of color, getting “educated” in America is to be cudgeled relentlessly with messages about how oppressed, exploited, and powerless we are, and how white people need to “get it together” to change this (but probably never will). Narratives like these grew especially pronounced during the post-2011 “Great Awokening.” The internalization of these messages may contribute to the observed ideological gaps in psychic distress among women and people of color.37

The cost of the lie is paid as damage to our perceptions of black and white race relations. Gallup has polled Americans on this almost every year since 2001.38 In 2001, 70 percent of black Americans said race relations were good. In 2021, not even half as many, 33 percent, could make that affirmation. The drop-off began in earnest in 2013, right around when use of terms like “racism” began to rise spectacularly in the media,39 and the newly formed Black Lives Matter began its messaging campaign.

The cost of the lie is not only ill-conceived campaigns to “defund,”40 but also damage to (already strained) trust between communities and police, especially black communities, whose disproportionate victimization by criminals shows they need policing, good policing, the most.41 The cost of the lie is black Americans’ sense of alienation within their own country. The cost of the lie is the creation of preconditions for destructive rioting the next time a cop is caught on camera killing a black person,42 whether under legally justifiable circumstances (such as to save lives) or not.

There is a final cost to be reckoned with. Police killings do not ultimately constitute a distinctly “black” issue, and a narrative that casts it as such has inherent limitations. First, the narrative’s framing is divisive: there are “black” issues and there are “white” issues, but there are no “American” issues that affect us all. This framing requires activists to leverage enough guilt or empathy among Americans who are not black to enact a “black” agenda of reform. Moreover, the “hunting black people” narrative is impotent to make common cause with those seeking justice for unjustified police killings of people of other races. (Almost half of the people killed by police are white.43) This impotence undermines the possibility of a broad-based, nonpartisan movement for reform.

For example, when police (both, as it happens, Latino) in Fresno, California, killed an unarmed white teenager, Dylan Noble, in 2016, and the killing was caught on video,44 Noble’s friends, family, and sympathizers initiated months of protests. But when protesters displayed “White Lives Matter” placards, perhaps inspired by Black Lives Matter, they were predictably decried as “racist.”45 What if there had been a movement for police reform not based on identity politics with which Dylan Noble’s family and supporters could have made common cause? Later, a young black man, a rapper, Justice Medina, organized a protest in Fresno for all the lives lost to police violence, including that of Dylan Noble. He named Dylan Noble in one of his songs, and he sought to distance himself from BLM: “I’m out here for the human race,” he said.46

Medina is precisely right: police reform is not well addressed through identity politics, in which one group’s grievances are pitted against another group’s perceived sins, biases, and privileges. The issue of police violence falls instead within the broader purview of American identity, which emphasizes our mutual bond and shared interests as citizens. Writing of the killing of a white woman, Hannah Fizer, by a police officer in June 2020, Adam Rothman and Barbara Fields point out that “a successful national political movement must appeal to the self-interest of white Americans” and advise that “those seeking genuine democracy must fight like hell to convince white Americans that what is good for black people is also good for them.” Only in this way will we find “the basis for a successful political coalition rooted in the real conditions of American life.”47

The upshot is that virtuous lies, whether about the police or about any other matter of concern, will get us nowhere. Only if the media and knowledge-producing classes eschew such lies and hew closer to the truth can we hope to depolarize our discourse, restore faith in our information-generating institutions, and bring together a broad swath of the country in solidarity to confront the challenges that face all of us as American citizens.

-

[ Sources: see Notes. ]

#Jake Mackey#Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn#live not by lies#virtuous lies#legacy media#virtue signal#virtue signalling#virtue signaling#implicit bias#police shooting#police killing#religion is a mental illness

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 2017, a young Black woman of Togolese descent, TG, visited the emergency department due to distress and panic attacks related to previous sexual assaults. She was admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit and diagnosed with psychosis. Upon discharge, she was prescribed perphenazine, a first-generation antipsychotic with greater side effect risks. Despite her symptoms being primarily related to mood and trauma, her dosage was increased by subsequent providers. In 2021, a team at Yale Department of Psychiatry determined that she had been misdiagnosed with schizophrenia due to racial bias. After a thorough review of her medical records and social history, TG received a re-diagnosis of major depressive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. Adjusting her medication led to a significant improvement in her depression, anxiety, and panic attacks.

In an article published in Harvard Review of Psychiatry, physicians at the Yale Department of Psychiatry present the case of TG to explore the mechanisms behind what they call “psychiatry’s longest-standing inequities born of real-time clinician racial bias” and its iatrogenic harm to patients who come to seek their help for other mood or trauma-related disorders. They write:

“For TG, she had consistently been telling providers about her sexual trauma for years only to have ED and outpatient providers doubt her report of abuse as a possible ‘delusion.’ During her second ED encounter in August 2018, documentation depicts her testimony using appallingly insensitive language, including ‘increasingly bizarre statements about supposed rape.’” Here, we can see how “biased perceptions of dishonesty intersect with bias against believing sexual assault survivors.”

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Disney Double Feature: Zootopia

Date: January 30, 2025

Day: 30

Content Watched: Zootopia

Year: 2016

Rating: PG

Run Time: 1 hr. 48 mins.

Why pair Zootopia with Fantastic Mr. Fox? It wasn't actually the con artist foxes that drew me in here, but the repeated mention of being wild animals. Now, I know a lot of people who don't like Zootopia. I'd even to hazard to ask which of these two movies were better, my husband and I would have opposite answers. But after watching it for what is only the second or third time, I feel it holds up pretty well. Let's talk about why.

First off, the animation. Now, Zootopia didn't wow me the way say, Loving Vincent did, but I can apprreciate what it did. The first scenes in Zootopia are evidence of why someone would want to make this film in the first place. There are some great visuals here--with all the animals of all different sizes milling about, and all the different additions the city has to function with so many different people living in it. There are tubes for the hamsters to get around, a giant air dryer for hippos who swim to work, a chute to get coffee up to giraffes. They even have a lot of visual humor, from the famous sloth DMV scene to the wolf in sheep's clothing as one of the police officers is given an undercover assignment at the end. And the animals themselves have all the standard mannerisms, like the movement of Judy's nose and Nick's ears. Plus, the opening shots of the city as Judy rides the train in are gorgeous, and some of the camera angles are really interesting too. As far as movement, there's plenty with all those people milling about the city, and no real static shots. Zootopia, like Persepolis and The Wind Rises, feels populated.

But I also really like the themes of Zootopia. Particularly, I like how the film shows that implicit bias is both prevelent and difficult to escape. Right from the beginning, Judy suspects Nick of being up to something shady because he's a fox. And even though she's told her parents that she doesn't believe their fear of foxes, she's still armed with her fox repellent, just in case. Even though she doesn't think of herself as biased, and she wants to believe she's not biased, she is.

This happens to all of us. No one free of making assumptions or having assumptions made about them. We assume innocence based on skin color, hobbies based on gender, education based on accent, work ethic based on weight, and intention based on ignorance. This is what I like about Zootopia. From "don't call me cute" to "you're a real... articulate fella," to the final scene in which Flash the sloth is speeding around town, everyone makes assumptions, and everyone has assumptions made about them. Incorrect assumptions are at the heart of the film.

All this brings me to this video that's been popping up on my YouTube feed for a while. Since I was watching Zootopia, I thought I'd give it a watch too, and the creator has some pretty valid things to say.

youtube

I love this take on Zootopia. I love the things they noticed that I didn't, like Nick's surprise that Judy's family also grows blueberries being another sign of his own bias. And they point out just how important it is when Judy tells Nick "you're not like them." Again, we are all susceptible to believing individuals are exceptions to a rule rather than evidence that the rule is invalid. Truth be told, I don't know if I would have stopped to mention this scene if it hadn't been for the video. I'd have mentioned "if the world's only going to see a fox as shifty and untrustworthy, there's no point in trying to be anything else." Because this movie also shows us how we trap people into boxes with our assumptions--something that also happens to both Nick and Judy.

This is why I'm not sure that the original Zootopia movie they mention, with the shock collars, would work for me. While I think they have a point about the themes being simplified, I think this might simplify it too far in the other end, and might take away from this idea that Judy is also the victim of implicit bias. That everyone is. I do agree that more could be done to show that these are ingrained within us. That we pick them up from our parents and from society at large and don't even really notice. But I don't think the shock collars are the only way to have done this.

The shock collars could be a dark history of Zootopia. Or they could have even just had more world-building in that opening pageant to tell us how predators and prey came to live together and wear clothes and use cell phones in the first place. (Which would also give us more time with that lion cub doing the music. He's my favorite!) I'm not saying I have a problem with the conceit, but they could have used it to build centuries-long ingrained biases. Some kind of additional history or depiction of how we pick these things up from our parents could have jelled that. As for their complaint that everyone goes into a panic overly quickly about the predators going savage, I found it believable. Like Bellweather says, "fear always works."

Which leaves me with the complaint about coincidences. And when they line them all up... well, I guess that's a lot of coincidences. And yet, these don't bother me either? Sure, she just happens to have a run in with Nick, and that just happens to give her a clue, and the villain is barely in the story, but these are things I expect from procedurals. In fact, these are things I expect from mystery novels. When I read Listen of the Lie, I thought Matt was going to be the killer... until people started talking about him. Then I sat down and thought, "hmm... whose been on the periphery this whole time." Now, if you're going to tell me that's no excuse, especially considering the hissy fits I threw over Asami and "The Beach," well... you're right. It is no excuse. But it does reveal that I hold ATLA and Korra to higher standards that I hold Disney. Why? I don't know, actually. My best guess at the moment is that the creators of ATLA have proven that they hold themselves to a higher standard, and Disney seems less interested in telling good stories than it is about selling plushies. But if you have a different reason, let me hear it. Maybe it's just another implicit bias of my own.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"No one ever says dismissively of a potential CEO candidate that he's too short. This is quite clearly the kind of unconscious bias that the IAT [Implicit Association Test] picks up on. Most of us, in ways that we are not entirely aware of, automatically associate leadership ability with imposing physical stature. We have a sense of what a leader is supposed to look like, and that stereotype is so powerful that when someone fits it, we simply become blind to other considerations.

And this isn't confined to the executive suite. Not long ago, researchers who analyzed the data from four large research studies that had followed thousands of people from birth to adulthood calculated that when corrected for such variables as age and gender and weight, an inch of height is worth $789 a year in salary. That means that a person who is six feet tall but otherwise identical to someone who is five foot five will make on average $5,525 more per year. As Timothy Judge, one of the authors of the height-salary study, points out: 'If you take this over the course of a 30-year career and compound it, we're talking about a tall person enjoying literally hundreds of thousands of dollars of earnings advantage.'"

- Malcolm Gladwell, from Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking, 2005.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have a diagnosed girlboss-malewife bias.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

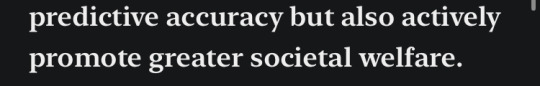

By: Mahzarin Banaji and Frank Dobbin

Published: Sep 17, 2023

At least 30 states are considering legislation to defund DEI initiatives in public universities and state agencies. At the same time, conservative activists, emboldened by the Supreme Court’s ruling against affirmative action in college admissions, are suing companies to stop DEI initiatives. These challenges come on the heels of the growth of corporate DEI programs after the murder of George Floyd in May of 2020.

Meanwhile, advocates for DEI—which stands for diversity, equity and inclusion—have bemoaned the fact that after decades of diversity training, many university faculties, state agencies and corporations have made little progress on diversifying the workforce.

Are the right and the left on the same page here—is diversity training a hopeless cause?

We are a psychologist and a sociologist who have been studying bias and organizational diversity programs, respectively, for decades. The research makes it clear that Americans desperately need education about bias, because even people who value fairness and equality hold biases—without being aware of it. They need to understand that bias operates systemically and must be addressed at the individual, institutional and societal levels.

Education offered on these matters is very much in the national spirit. As Alexis de Tocqueville noted in “Democracy in America” in 1835: “The greatness of America lies not in being more enlightened than any other nation, but rather in her ability to repair her faults.”

What research shows

The social and behavioral sciences have developed strong evidence about conscious prejudice and implicit bias. Three lines of research, together, are pertinent. One provides good news. As our colleague Larry Bobo has documented, conscious unabashed racial prejudice has fallen consistently since the 1960s. White Americans today largely believe in racial equality.

This isn’t to say that explicit expressions of prejudice have evaporated; in fact they pop up with surprising regularity. The pandemic witnessed precipitous increases in anti-Asian hatred, and according to the Anti-Defamation League, instances of antisemitism are at a record high.

A second line of research shows that less conscious, or implicit, bias has declined more slowly. Bias against some groups has barely budged. If only explicit values and biases drove discrimination, unfair treatment of, say, Black workers would be low. But implicit bias taints employer behavior and decisions. Our colleague Mandy Palais and collaborators find, for instance, that implicit racial bias in grocery-store managers still influences worker performance.

A third line of research uses audit studies, in which matched Black and white people, for instance, apply to the same job. Who gets called in for an interview, or hired? Scores of studies show discrimination by race, ethnicity, gender and disability. These studies show, among other things, that white applicants are about 50% more likely than identical Black applicants to be called back for an interview or offered a job. Other audit studies show discrimination in real-world access to financial resources, healthcare and treatment by the law and law enforcement.

Research by Lincoln Quillian and colleagues compares the results of audit studies over time, finding that discrimination against Black job applicants is virtually unchanged from a generation ago. And the economist Raj Chetty and colleagues not only show a shocking drop in American upward mobility over time, but also show that in regions with high levels of implicit bias, Black Americans are less likely than white Americans to move up the economic ladder.

Research by Lincoln Quillian and colleagues compares the results of audit studies over time, finding that discrimination against Black job applicants is virtually unchanged from a generation ago. And the economist Raj Chetty and colleagues not only show a shocking drop in American upward mobility over time, but also show that in regions with high levels of implicit bias, Black Americans are less likely than white Americans to move up the economic ladder.

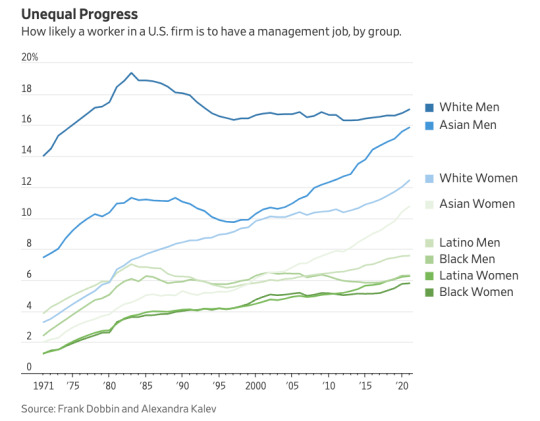

Research from one of us, Frank Dobbin (with Alexandra Kalev), meanwhile, shows how likely a worker in a U.S. firm is to have a management job, by group. Women and people of color see increases until the mid-1980s. But progress stalls for Black and Hispanic workers after that. Men from those groups make no progress between then and 2021, and women make almost no progress. We clearly have more work to do to equalize opportunity.

Falling short

It’s not hard to conclude from all these studies that we are not the land of opportunity for everyone we claim to be. An enlightened society should see that education about the prevalence of discrimination is imperative. In fact, it would be downright dumb not to educate people.

But, as Dobbin and Kalev have shown, the typical DEI training doesn’t educate people about bias and may even do harm.

Most training programs fall short on two fronts. First, they use implicit-bias education to shame trainees for holding stereotypes. Trainers play gotcha, sending trainees to take an online test co-developed by one of us, Mahzarin Banaji, for education and research. Instead of training people about research that finds that bias is pervasive, trainers use the test to prove to trainees that they are morally flawed. People leave feeling guilty for holding biases that conflict with American values.

“Gotcha” isn’t going to win people over. The approach is disrespectful, and misses the main takeaway from implicit bias research: Everyone holds biases they don’t control as a consequence of a lifetime of exposure to societal inequality, the media and the arts. Trainers should introduce these ideas with humility, for trainers themselves can’t help but hold these very biases. They could easily educate themselves about the implicit bias research with resources at outsmartingimplicitbias.org.

The second problem with most trainings is that they seek to solve the problem of bias by invoking the law to scare people about the risk of letting bias go unchecked. Trainers recount stories of big companies brought to their heels by discrimination suits. They detail rigid do’s and don’ts for hiring, disciplining and firing people. They require trainees to pass tests on what the law forbids. All of this makes it clear that the CEO approved the training solely to avoid litigation. Trainees leave scared that they will be punished for a simple mistake that may land their company in court.

Trainings with this one-two punch—you are biased and the law will get you—backfire. The research shows that this kind of training leads to reductions in women and people of color in management.

Why would diversity training actually make things worse? Making people feel ashamed can lead them to reject the message. Thus people often leave diversity training feeling angry and with greater animosity toward other groups (“There’s no way I’m biased!”). And threats of punishment, by the law in this case, typically lead to psychological “reactance” whereby people reject the desired behavior (“Nobody’s telling me what I can’t say!”). This kind of training can turn off even supporters of equal-opportunity programs.

A better way

It doesn’t have to be this way, and Dobbin and Kalev’s research on training points to a better alternative. Instead of using legal scare tactics, training programs should give managers a way to counter biases—namely, training in strategies for cultural inclusion. This kind of training teaches skills in listening, observation and intervention. It thus helps managers to hear employee concerns, notice when workers are feeling shunned or dissed, and intervene. It also offers skills for starting tough conversations about how to treat colleagues at work.

Those are skills from Management 101, but managers often don’t want to hear bad news, so they don’t ask employees about troubles, watch teams for signs of bullying, or speak up when they sense a problem. Reminding managers that they can use these tools to suss out problems and nip them in the bud helps them to feel capable of managing biases and microaggressions. When managers use these skills, they retain women and people of color for long enough to come up for promotion. That’s how good diversity training can boost diversity. Unfortunately, only about a quarter of diversity trainings emphasize cultural inclusion.

Moreover, if training succeeds in conveying the findings from bias research—that bias is unseen but pervasive—it can build support for wider systemic changes designed to tear down obstacles to equal opportunity. In that sense, training isn’t designed to blame people for their moral failings. Instead, it’s galvanizing them to support organizational change by arming them with knowledge.

In the end, DEI training can’t squelch implicit bias; nothing short of changing people’s life experiences can do that. But when done right, implicit-bias education can alert students to the fact that people committed to equality nonetheless hold biases. And that knowledge can, in turn, motivate them to reshape their workplaces to counter discrimination by democratizing key parts of the career system.

That means extending recruitment visits from Harvard to Howard; offering mentors to each and every worker; and inviting all employees to nominate themselves for skill and management training programs. It means offering work-life supports to people up and down the ladder. Each of these changes has been shown to produce significant increases in managerial diversity.

The lesson here, the one that should be at the core of DEI training, is that implicit bias resides in individuals, but it resides in organizational career systems as well. And fixing those systems is as simple as democratizing them.

Mahzarin Banaji is a professor of psychology at Harvard University and co-author of “Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People.” Frank Dobbin is a professor of sociology at Harvard University and co-author of “Getting to Diversity: What Works and What Doesn’t.” They can be reached at [email protected].

[ Via: https://archive.is/0D4kV ]

==

#diversity training#DEI training#implicit bias#implicit association#implicit bias test#implicit association test#diversity equity and inclusion#diversity#equity#inclusion

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Link to a bunch of Harvard Implicit Bias tests:

Project Implicit is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and international collaborative of researchers who are interested in implicit social cognition.

Project Implicit was founded in 1998 by three scientists – Dr. Tony Greenwald (University of Washington), Dr. Mahzarin Banaji (Harvard University), and Dr. Brian Nosek (University of Virginia). Project Implicit Health (formerly Project Implicit Mental Health) launched in 2011 and is led by Dr. Bethany Teachman (University of Virginia) and Dr. Matt Nock (Harvard University).

The mission of Project Implicit is to educate the public about bias and to provide a “virtual laboratory” for collecting data on the internet. Project Implicit scientists produce high-impact research that forms the basis of our scientific knowledge about bias and disparities.

Please visit https://www.projectimplicit.net to learn more about our team and the programs and services that we offer.

0 notes

Text

This is especially very very important for my fellow healthcare workers. Healthcare in general is not very inclusive for fat people and unraveling your own personal biases is necessary to truly provide good care for your patients.

You know I wish fatphobia was less pervasive. Even among people who consider themself as progressive, it's rampant. So quick reminder. No it's actually not easy to stop being fat, and it sucks that we are treated differently for something we really can't control. Shaming a fat person for being fat, and shaming them for not having the "willpower" to become skinny- is bigotry. And if all you talk to fat people about is weight loss and dieting- congratulations! You're being a dick! Stop.

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

There really is something so morbid about Empire: Total War Sure, in the moment, you make your stupid jokes to yourself, or your friends who know you're not like that, about how awful you are, dropping quicklime shells on civilian militias and indigenous tribes. But when you take a step back from the obvious horror of what you're doing, so normalized by the Total War experience that you hardly bat an eye, the real horror sets in when you look at your empire. After all, why would you preserve indigenous religions, Islam, or Hindu, or even other types of Christian populations? They'll just cause religious tensions, there's no benefit to keep them around. Why would you keep indigenous buildings? Their farms, their homes, their way of life? You can't upgrade them any further - that indigenous religious site will make a much better Protestant religious school, or a cloth mill if you've already got the conversion of the region underway. Why not industrialize? You worked hard for that steam power research - it's not like the game models pollution, some people just get upset. Train some more police dragoons. Whatever you have to do to calm them down, it'll pay for itself in tax income down the line. The game almost encourages this - Indigenous and Indian units are kinda crap, making the game brutally Eurocentric. The Ottomans at least get Nizam I-Cedit units late-game which can go toe-to-toe with Europe. But elite Indigenous units can lose in a straight, fair fight with common European units, even if they manage to close to melee unmolested by musketry and cannon fire. And even the most elite Maratha musketeers can't Fire by Rank or Platoon Fire, abilities that make even basic European Line Infantry utterly dominant over enemies that don't have it for sheer rate and volume of fire. Even the statistically superior Sikh Musketeers will still get eaten alive by a common Line Infantry if they stand and fight at ranged. Whole stacks of Barbary Galleys will lose to a handful of Ships-of-the-Line, surrendering after a few thundering volleys. Playing as anyone but a European faction or the US is basically a challenge run. And by the time you've had your fill, by the time your coffers overflow with cash and your armies are unchallenged on three continents, there's absolutely no reckoning with what you did. You even get a triumphant cutscene, customized for if you're an absolute monarchy, constitutional monarchy, or a republic. You get off scot-free, like so many of history's unsung monsters who marched upon others, stomping them into the dust, annihilating cultures and religions that we will never get back. By being such a pure wargame, one that abstracts away genocide and slavery and assimilation to give you some good ol' fashioned 18th century musketry and bloodshed, Empire: Total War is probably the closest I come to understanding the colonialist perspective - because the people making those decisions never had to meaningfully confront what it meant to bring such violence to those people. They just saw the treasury filling and their color spreading on the map.

#total war#empire total war#total war empire#colonialism#anti colonialism#anti colonization#tw: guns#tw: death#tw: violence#tw: genocide#implicit bias#eurocentrism

0 notes

Text

The Hidden Forces Shaping How We See the World: Implicit Bias, Social Categorization, and Prejudice

Discover how implicit bias, social categorization, and prejudice shape our interactions and decisions. Learn actionable strategies to break down assumptions, foster empathy, and build a more inclusive world. 🌍✨ #ImplicitBias #SocialCategorization #Prejud

Have you ever made a snap judgment about someone without even realizing it? Maybe you assumed something about a stranger based on how they dressed, their accent, or even their name. These automatic assumptions aren’t just personal quirks—they’re deeply rooted in how our brains are wired. In this post, we’ll explore the invisible forces of implicit bias, social categorization, and prejudice that…

#discrimination#diversity#emotional intelligence#empathy#equity#implicit bias#inclusion#prejudice#social categorization#social justice#social psychology#stereotyping#workplace diversity

0 notes

Text

The Only Woman in the Room: Why Science Is Still a Boys' Club | Eileen Pollack

Eileen Pollack’s The Only Woman in the Room: Why Science Is Still a Boys' Club offers a piercing insight into the systemic barriers faced by women in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics).

The Only Woman in the Room: A Call for Change in STEM Introduction Eileen Pollack’s The Only Woman in the Room: Why Science Is Still a Boys’ Club offers a piercing insight into the systemic barriers faced by women in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics). Drawing from her personal experiences as one of the first women to graduate with a physics degree from Yale University in…

View On WordPress

#Audre Lorde#bell hooks#Chimamanda Ngozi#Eileen Pollack#gender#gender bias#gender inequity#implicit bias#memoir#STEM#Virginia Woolf

0 notes