#I wish he had some like

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

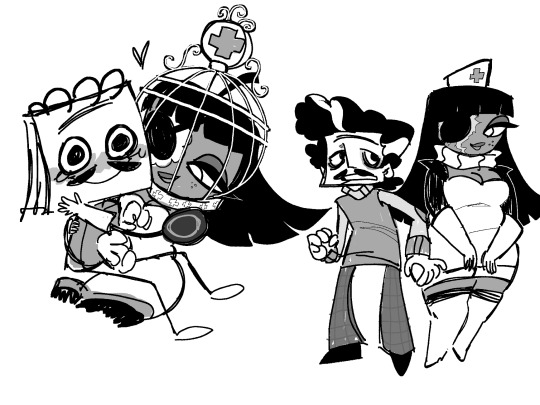

PSYCHONAUTS LBP 2 AU??? More likely than you’d think

In the au, the alliance area group of inventors ! And they make a basically sentient computer run on psitanium. Said computer is the negativatron in this scenario, it turns on them, wanting to destroy anything related to imagination and invention, which is pretty much everything lol. Since it’s psitanium powered it can do this thing where it messes with the mental worlds of the alliance. Basically setting it on fire and putting the monsters in there like it does in canon. In this au raz would have to help them by going into their minds and eventually defeating the negativatron ! Essentially taking the place of sackboy. It would take place after psychonauts 2 for Raz, so he’s basically just going around collecting parental and grandparent figures lmaooo. I imagine he’d get roped into it the same way sackboy would, he’s just wandering around doing raz stuff before he almost gets sucked up by the negativatron and Larry saves him !

#I’m really happy with all of there designs !!!#except Larry lol#LISTEN there’s not much to work with for him outfit wise and grandpa forgot his own name he’d forget to get dressed in the morning too-#I wish he had some like </3 newspaper motifs in his design still but I couldn’t figure out how to incorporate it#my art#psychonauts#razputin aquato#psychonauts fanart#psychonauts art#raz aquato#psychonauts raz#psychonauts razputin#psychonauts au#little big planet#little big planet 2#little big planet fanart#lbp avalon#lbp clive#clive handforth#avalon centrifuge#victoria von bathysphere#larry da vinci#Eve sliva paragorica#herbert higginbotham

574 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyperallergic: Minoru Onoda, Circle Master from Japan’s Gutai Group

Minoru Onoda, Work 64-W, 1964; oil, gofun and glue on plywood; 36 1/8 x 36 1/8 x 1 3/4 inches (photo © Estate of Minoru Onoda, courtesy of Anne Mosseri-Marlio Galerie)

BASEL, Switzerland — Beyond the orgy of art-world hype surrounding the annual Art Basel fair, the gallery scene here in its host city and its environs is as varied as it is compact; operating in the shadow of the venerable Kunstmuseum Basel, the repository of some of Europe’s finest modern and medieval art collections, including the vast holdings of drawings, watercolors, and prints in its Kupferstichkabinett division, these local galleries know how to put on a good show, especially when the high-profile Art Basel fair rolls into town.

Just a few blocks from the Kunstmuseum, for example, Anne Mosseri-Marlio Galerie is presenting Maru (“Circle” in English), an exhibition of paintings by Minoru Onoda, a member of Japan’s post-World War II, avant-garde Gutai group. As I noted in a recent Hyperallergic Weekend article about Onoda’s Gutai confrère, Toshio Yoshida, the Gutai Art Association, as their collective was officially known, was founded in 1954 by the businessman-turned-painter Jirō Yoshihara and more than a dozen younger art-makers from Osaka and Kobe.

The Japanese artist Minoru Onoda (1937-2008), a member of the avant-garde Gutai Art Association, making a kite in 1988 (photo by Paul Eubel-Plag, © Estate of Minoru Onoda, courtesy of Anne Mosseri-Marlio Galerie)

In recent decades, such Gutai artists as Atsuko Tanaka (1932–2005), Kazuo Shiraga (1924–2008) and Sadamasa Motonaga (1924–2008), among others, have earned critical recognition apart from their influential association’s collective label. Now, with dealer Anne Mosseri-Marlio’s Basel presentation, it’s Onoda’s turn in the spotlight. On view through July 14, Maru is the first-ever solo showing outside Japan of works by this artist, who was born in Japanese-occupied Manchuria, China, in 1937 and died in Japan in 2008.

At its core is a selection of paintings Onoda produced during the first half of the 1960s, before he became a Gutai member. In them, he worked out what would become the fundamentals of his signature formal vocabulary. Organized by Mosseri-Marlio in conjunction with the painter’s son, Isa Onoda, an artist and art teacher based in southern Japan, this concise survey includes a few pieces from later decades, too.

One of the Gutai artists’ motivating principles was to honor — and, in effect, to reveal — the inherent expressive properties of their materials without trying to cunningly manipulate them. So was their determination to create works of radical originality: Tanaka made a “dress” of colored electric light tubes; Shōzō Shimamoto made “paintings” of newspaper sheets stretched on frames and punched through with holes; Shiraga painted with his feet; and Motonaga explored the accidental beauty of big, drippy, majestic blobs in color-saturated pictures.

Close-ups of artist Minoru Onoda’s paintings from the early 1960s showing their undulating, textured surfaces made with gofun, a Japanese, moldable paste (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Onoda, whose father had worked as a policeman in Japanese-controlled Manchuria, was still a boy when his family moved back to Japan before World War II ended, settling in Himeji, to the west of Kōbe. He went on to study art in Osaka (later he would say he enjoyed reading van Gogh’s biography and letters); by the mid-1950s, having assimilated Western modernist techniques, Onoda was producing paintings of traditional Japanese houses and other buildings, but toward the end of the decade he began making stylized images of flattened, rectangular human figures.

Like the other Gutai artists, he became aware of post-WWII European, art informel forms of abstract painting but eventually dismissed them as merely resembling walls. Yet his own works, which he actively exhibited in group shows, became more abstract themselves, incorporating thinly cut, circular slices of PVC pipe laid flat against their surfaces and slathered with paint to produce rich textures.

Minoru Onoda, Work 61-14, 1961; mixed media on plywood; 36.14 x 52.36 inches (photo © Estate of Minoru Onoda, courtesy of Anne Mosseri-Marlio Galerie)

In 1961, a Himeji-based art magazine published a text Onoda authored about what he dubbed “propagation painting.” In it, he observed that art informel, whose influence had been felt in Japan for several years, had become so “safe” and “accepted” that it had “los[t] its initial drive for negation and rebellion.” Citing his own efforts to “make a cynical critique,” and what he called his “obsession” with the notion of the mechanical duplication of just about anything, Onoda ditched his sculptural PVC circles and began painting endless maru — circular dots — in sprawling, eddying, seemingly random patterns of essentially primary colors, with streams of smaller and larger colored dots flowing into real gullies and broad valleys on the surfaces of his pictures.

That’s because Onoda used glue and traditional Japanese gofun, a moldable paste made from pulverized oyster and clam shells, to produce bas-relief mounds on their gently undulating, thick plywood surfaces; this kind of experiment in oil-painting technique is exemplified in such pieces on view as “Work 63-12” and “Work 63-13” (both 1963), which are narrow and vertical in format, and “Work 64-W” (1964), a large, hippy-trippy, psychedelic square. They’re colorful, dynamic, peculiar — and hypnotizing.

Minoru Onoda, Work 63-12 and Work 63-13, both dated 1963; oil, gofun and glue on plywood; each piece 40 x 10 1/8 inches (photo © Estate of Minoru Onoda, courtesy of Anne Mosseri-Marlio Galerie)

(It’s tempting to compare Onoda’s dot-making obsession with that of another Japanese modernist, Yayoi Kusama, who famously painted dots on the naked bodies of participants in her New York happenings of the late 1960s, but her evolving use of the motif could be variously spectacular, mysterious, or elegantly decorative. In interviews and in her writings, Kusama has explained that her obsessive-repetitive use of certain motifs was motivated more by particular psychological-emotional impulses than by the kinds of formal, aesthetic, or intellectual concerns Onoda expressed in relation to his art.)

It was Motonaga who brought Onoda into the Gutai Art Association in 1965. That year, Onoda showed his work in the collective’s 16th group exhibition, which took place in Tokyo; he would continue to take part in every regular, similar presentation until the association disbanded in 1972, following the death of its leader, Yoshihara.

By that time, Onoda’s art had evolved in many ways. In 1970, for example, artists associated with Gutai produced an array of action-based performances and multi-media works for the world’s fair, Expo ’70, which took place in Osaka; Onoda’s mixed-media contributions attempted to humanize that era’s emerging technologies through the use of sound sensors, moving walls, and interactive features.

Minoru Onoda, Work 70-G2, 1970; oil, gofun and glue on plywood; 27 1/8 x 23 5/8 x 3 1/2 inches (photo © Estate of Minoru Onoda, courtesy of Anne Mosseri-Marlio Galerie)

In the current Basel show, such pristine, precise, geometric abstractions as “Work 70-G2” (1970; oil, gofun and glue on plywood) and “Work 75-Blue 9” (1975; acrylic on plywood), feature big, finely rendered groups of concentric circles (some of which are made up of countless dots, of course); here the artist can be seen pushing his ideas forward technically and formally, bringing his visual language in line with the harder-edged, tech-romancing, design-flavored aesthetic that characterized a lot of 1970s art, for better or worse.

“Watashi-no maru (‘my circles’) will extend out of the picture, not only to the wall and ceiling, but to the road and the car,” Onoda once wrote, daydreaming about the power of his favorite, inexhaustible art-making motif. His dot- or circle-filled “propagation paintings,” he believed, would somehow poke a defiant thumb in the eye of “the world we are now living in.”

“Looking up at the sky vacantly,” he also observed, “I dream that this sky and the world will be filled completely with watashi-no maru.” He compared the proliferation of his key motif of the 1960s to microorganisms and declared, “My wish is that these bacteria will spread all over the world.”

Isa Onoda and art dealer Anne Mosseri-Marlio at Anne Mosseri-Marlio Galerie in Basel, Switzerland, examining photo sheets showing works from the different phases of artist Minoru Onoda’s career (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

As it turned out, before that rash of circle-dots could break out in an all-enveloping inundation, Onoda’s art evolved through several distinct phases. In Basel, his son Isa showed me photos of his father’s late red-on-black, blue-on-black, and black-on-black painted-plywood-on-painted-plywood paintings, in which loosely rectangular forms with perforated edges lie like flattened sheets of pie dough against pitch-black grounds.

As the evidence of such works makes clear, ultimately, Onoda’s aesthetic gears shifted with the passage of time, as his creative focus moved from dizzying oceans of colored dots to quiet, sober essays in pure form (one of which, “Work 84-12-I,” 1984, is on view in Basel). In the very last series of paintings he produced, between 1994 and 2008, big, dense, semi-transparent patches of black and blue, layered on top of each other with broad brushstrokes, seem to float above white backgrounds; they function more as symbols of tightly concentrated energy than of ominous foreboding.

At the gallery, Isa Onoda told me, “Looking back over the span of my father’s art-making experience, from one creative phase to the next, he seemed to stay true to Gutai’s spirit of innovation and deep engagement with his materials. There is something new to be found in the works of each phase.”

Minoru Onoda, Work 75-Blue-9, 1975; acrylic on plywood; 31 1/2 x 31 1/2 x 1 3/8 inches (photo © Estate of Minoru Onoda, courtesy of Anne Mosseri-Marlio Galerie)

For now, this illuminating exhibition, which calls attention to yet another strong, personal, creative vision that helped shape Gutai’s collective ethos, is well worth a detour from the frenzy of Basel’s big fair.

Minoru Onada’s Maru continues at Anne Mosseri-Marlio Galerie (Malzgasse 20, CH-4052 Basel, Switzerland) through July 14.

The post Minoru Onoda, Circle Master from Japan’s Gutai Group appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2rqJ5t3 via IFTTT

0 notes