#I was so disappointed. I love it when we kill an oppressive god with friendship and violence. it's fun)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

From the moment Gale said that the Crown of Karsus could allow someone to ascend as a god, I was like... does that mean it could also kill a god? Maybe? Maybe even three gods? 👉👈😳

And I really wish there was a dialogue option where I could at least put the idea out there.

#bg3#I wanna kill Bhaal so bad you don't understand. even if you could only kill one god I'd be happy!#maybe even let the player choose which of the Dead Three (or maybe try to kill Mystra or Shar as well? though that'd be a bad end) to kill#I just wanna give Durge that moment of stabbing his dad/creator just like Astarion did with Cazador#plus three stones for the Dead Three. using the stones to kill them once they're weakened would be just... perfect#like... I feel if there was an act 4 or big dlc with the level cap reaching 20. that's where it'd go#finally freeing Baldur's Gate of those fucking assholes who keep crawling out of the sewers#and lore-wise I think the crown is one of the few things that could let you kill a god and the Dead Three fucked things up so bad#with their shitass plan that the other gods might even let us#like we have god killer rocks made by someone who (by accident) killed THE WEAVE ITSELF#and we DON'T get to murder a god?#and tbh the Dead Three seem kinda pathetic by god standards so I think we could wreck their shit#(you have no idea how happy I was when I learned we were gonna kill the Absolute--a GOD--but then it turned out to be a sham#I was so disappointed. I love it when we kill an oppressive god with friendship and violence. it's fun)#yes yes I know that in the end Withers implies that they fade#but I really wanted to outright kill them

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anyway, Peter Parker is Bi, and I Won’t Be Convinced Otherwise.

Firstly, we have to get our bases covered. What exactly is Bi-sexuality? What is sexuality?

Sexuality is defined as a persons identity in relation to gender(s) they are attracted to. Why is this important? Peter’s sexuality has never been specifically stated in the comics, nor in any other form of media. It’s assumed that he is straight because of his popular relationship with Mary Jane Watson in the comics, and the movies.

Now that we have a bases for what exactly sexuality is and how it’s defined, let’s go over Peter’s partners.

Obviously Peter and Mary Jane are a piece of comic book history. They eventually get married, though sadly, during the events of Civil War II (I think, don’t quote me) Peter and Mary Jane sell their marriage to Mephisto in order to save Aunt May

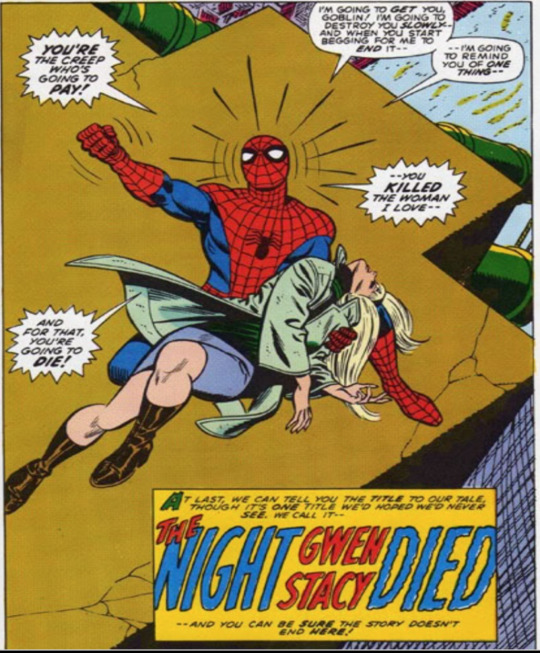

They later had their memories of their marriage restored, they have yet to get back together and it’s been a few issues if I remember correctly. Next we have Peter’s first, and most unfortunate love, Gwen Stacy.

They dated in high school where she later died. Of course, Peter has dated other people (namely, Black Cat, Betty Brant, Carol Danvers, Anna Maria, Cindy Moon, Lian Tang, and so on). Since we have his known history of heterosexuality out there, we need to move onto another important part of Peter’s Bi-sexuality. An important implication in any media, especially queer media though, and that is the homoerotic subtext.

Homoerotic subtext is important part of queer culture, a lot of the time it’s used to portray a characters queerness without saying it out (see: Dorian Gray by Oscar Wild or Great Gatsby By Fitz). In current decade, homoerotic subtext is often used for queer baiting or creating more realistic male friendships.

So what’s the difference between someone creating a health male friendship (or a character comfortable in their heterosexuality) and implying a character is queer?

Here are some examples of a healthy male character, both with himself and his friendships.

Clearly he’s just taking the shit, and messing around with Reed. He’s comfortable enough (or as I like to see it, so traumatized because good god this guy has been Spider-Man since he was 15 good god that’s awful. He probably doesn’t care anymore). Here are some examples of Peter a little more than just a straight man shooting the shit.

This has three meanings. Two of which I will take, one of which is just deeply embarrassing. Despite Peter’s history with humiliating events, I don’t think he would get his own spunk in his eyes. Leaving the other two options, he has experience getting spunk of - some kind - in his eyes, and/or he’s taking the shit again. Which is very likely.

Kissing a cop? For....no reason? A little not so hetero of you Peter.

You can practically hear his disappointment in his voice. Also could be read as taking the shit, but why would you.

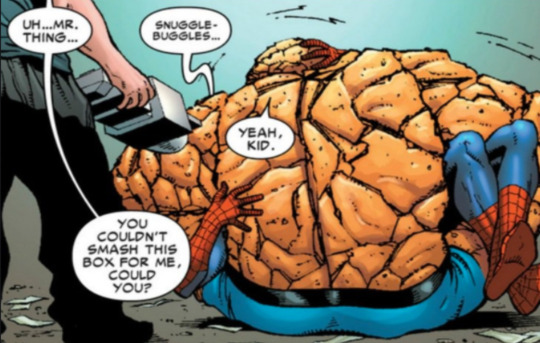

Making out with The Thing? Gay.

This one is the most important. Peter is clearly tired, annoyed by his teammates (see wolverine being wolverine in the corner). Shits on fire, its mid battle, and Peter has the audacity to mutter “I hate men” to himself. The only people I have every heard say this in that was are lgbt and straight women, and lgbt men. This kind of expression only comes from people who date, or deal with men in a completely different world than straight men. Straight men use this phrase as an endearment, “Oh have you seen Bill today, I hate that guy.” “Man Jerry can do so many push-ups, I hate that guy.” Very different language, and implications (I also, obviously don’t know how straight men speak).

Now that we’ve gone over our bases, and homoerotic subtext. How else could we gather that Peter Parker is Bi? There are many tropes in media - queer media - that allure to a characters queerness. Like homoerotic subtext, there are ways to tell an audience something without specifically saying it.

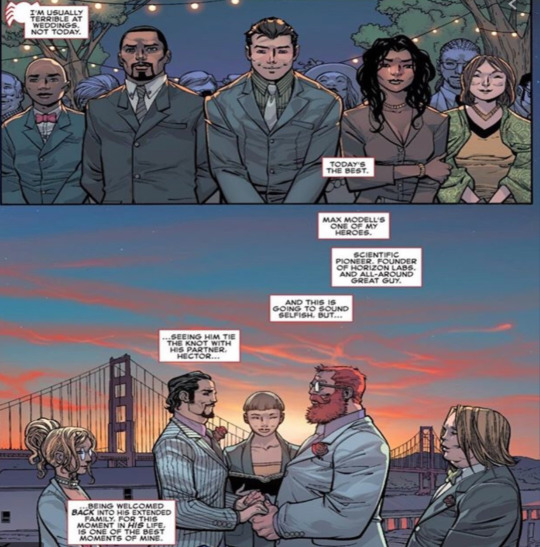

This is a gay wedding Peter went to in the recent comics. I don’t know if any of you have been to a gay wedding recently, but Peters face (the first panel above the wedding) is the same exact face I made at my first gay wedding. It’s the face of excitement for not only the couple, but for yourself. The hope that maybe, you too can actually be in a same-sex relationship.

I’m also going to allure to queer tropes as stated previously. Such as the real, and fictional trope of lgbt people sticking together. Thousands of years of belittlement and oppression will make groups of people not want to wonder out, and subconsciously look for others like them.

Johnny Storm (and Wade Wilson since he comes in later but I couldn’t find a picture of the confirmation) is cannon Bi-sexual (Pan-sexual).

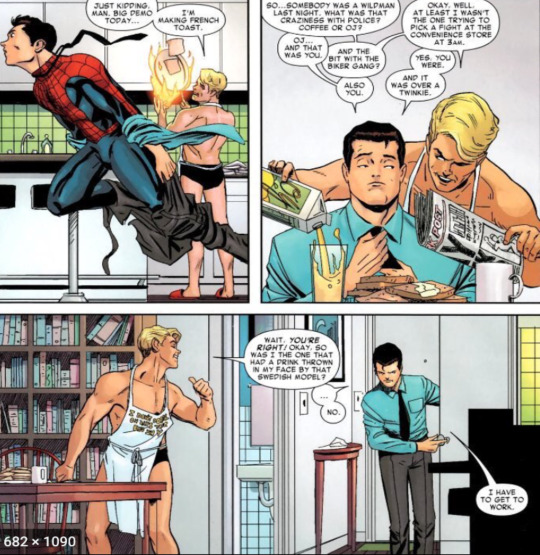

Their friendship is deeply homoerotic as most queer friendships in media and real life are. Johnny flirts with Peter on many occasions (saying his ideal women is a female version of Peter, inviting him over to watch is sex tape, and so on) and of course oh my god they were roommates.

Some other popular queer tropes are: Found Family, Soulmates, and Enemies to lovers. Because it’s superhero related, this includes the Identity Porn tag as well.

Peter Parker and Wade Wilson have a famous Love/Hate relationship. I mean, how could you expect anything less when your first meeting with this known mercenary is him throwing your civilian persona out the window of a car. Now, Wade still doesn’t know Peter is Spider-Man in the current run of comics, but that doesn’t make anything about them any less gay.

For the Found Family Trope:

Because it’s Peter and Wade, their whole development can be read as Enemies to Friends to Lovers, so I wont bother backing that up because, uh, it speaks for itself. One panel really does to add that cause though

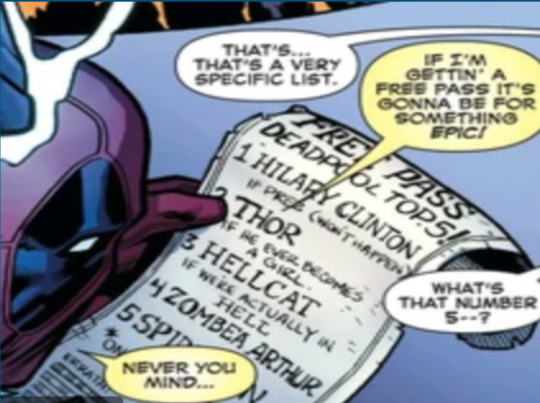

I’m not going to explain what a free-pass list is.

The Soulmates part I know I have to back up.

For SoulMates:

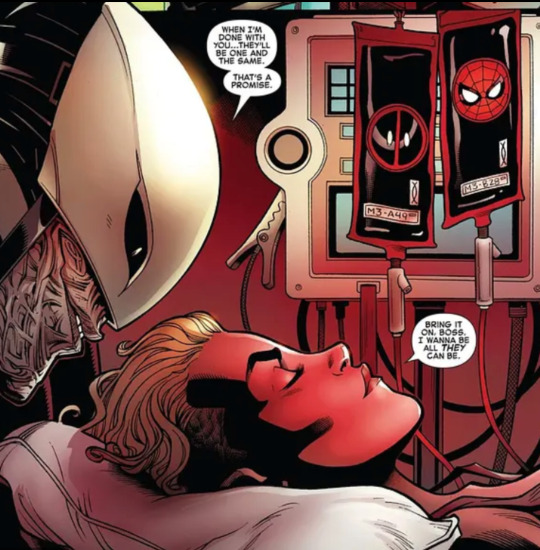

Now this panel requires a little explanation. Wade kills Peter, not knowing he’s Spider-Man. Weasel takes over for Peter (they don’t know its him) so no one suspects he’s dead. Deadpool begins to feel guilty he killed his best buds best bud, so he tries to bring Peter back to life. Losing his stunning good looks (switching back to how he looked before Weapon X making his wife Shiklah estranged (then she married Dracula but thats beside the point)). Spider-Man is Peter’s “true self” or patronus for Harry Potter fans. Wade is stupid and hasn’t connected the dots yet, effectively making him the biggest simp in history. Seriously, who destroys their marriage for the c h a n c e for getting some with their idol? A Simp, that’s who.

Peter forgives Wade for killing him (and for saving him from killing their genetic daughter itsy-bitsy). If someone killed me they better be hot as fuck before I even thing about forgiving them. Ignoring Peter’s super sexy forgiving nature, uh, he’s kinda simping.

Died in each others arms. Nothing else is needed.

They’re heartmates. From what I read, the feeling has to be mutual in order for it to work. The witches (long story, comics are hard to explain) that captured deadpool were expecting his wife so they could get the headmistress back. Instead, they got Peter. Basically Heartmates = soulmates but chosen for you instead of chosen by you.

To conclude my point:

Thank you for coming to my TED Talk.

#Peter Parker#Bi#Spider-Man#Deadpool#Johnny Strom#Mary Jane#He's bi and I wont be told other wise#thanks for coming to my ted talk#Bi-derman#bi wife energy#spideypool#spideytorch#he's gay but go off I guess marvel#aunt may#marvel#Fantastic Four#Reed Richards#The Thing#LGBT#Gwen Stacy#Anyways: the series

961 notes

·

View notes

Text

Malcolm Hawke (TV Tropes)

Ancestral Weapon: The Hawke's Key is the weapon he used to reinforce Corypheus's seals.

Badass Baritone: Once you hear his voice, you'll never want him to stop speaking.

Badass Creed:

"Be bound here for eternity, hunger stilled, rage smothered, desire dampened, pride crushed. In the name of the Maker, so let it be."

As well as his own personal mantra:

Malcolm: "Magic will serve that which is best in me, not that which is most base."

Badass Bookworm: Larius remembers him as a learned man, fascinated by the construction of the Warden prison.

Badass Teacher: In Legacy, Bethany says the other mages in the circle are very impressed by the extensive magical training she received from Malcolm.

Blood Magic: He was a blood mage, though a reluctant one, and he is regretful of that.

Dark Is Not Evil: Of all the Dragon Age franchise’s blood mages, he has the most understandable reason for ever using the stuff. He used it to seal away Corypheus, a tremendously powerful darkspawn. And he did this because the Grey Warden-Commander Larius threatened Leandra, whom the World of Thedas books confirm was pregnant with Areida Hawke at the time.

Call to Agriculture: When the Hawke family settled in Lothering, Malcolm hung up his staff and became a farmer.

Comes Great Responsibility: A lesson he lived by and taught his mage daughter, Bethany. If he were a Circle mage, he'd be the poster boy for the Aequitarian Fraternity.

Cursed with Awesome: He appears to have considered his magic a curse and it's revealed he deeply hoped that his children would not be mages, so they would be able to live a normal life. Things didn't turn out that way for at least one of his children, but he was a good dad anyway.

Dark and Troubled Past: According to the codex, Malcolm's past had more than its share of bloodshed and gave him lifelong nightmares. The most he was prepared to say about it was: "Freedom's price is never cheap, but that was a hundred leagues and a lifetime ago."

Deceased Parents Are the Best: His family practically worships his memory (even Carver). Every recollection is a positive one, and even negative revelations about him in Legacy are given a positive spin. Yes, he used blood magic to help the Grey Wardens imprison Corypheus, but he only did so because he was strong-armed into it when they threatened to kill Leandra and his unborn daughter.

Disappeared Dad: He died 3 years before the start of Dragon Age 2.

Family Eye Resemblance: Malcom’s striking blue eyes are the most noticeable physical feature that his eldest daughter inherited from him and how people could tell she was his daughter.

Generation Xerox: Areida is said to greatly take after, and physically resemble, Malcolm.

Guile Hero: A capable fighter and smooth-talker without using magic.

Heroic Neutral: See Call to Agriculture. Word of God is that he didn't actively work against the Circle like Anders; he just wanted to get out and have a quiet life. Larius had to threaten Leandra for him to help with the Corypheus issue. Malcolm made him both promise safe passage and pay through the nose for the work.

Heroic Vow: "Though I have left the Circle, I made a solemn vow: Magic will serve that which is best in me, not what is most base."

I Just Want to Be Free: Malcolm was an extremely powerful and knowledgeable mage, but wanted nothing more than a quiet life with his wife and children.

Magic Knight: Although he was always better at magic.

Magnetic Hero:

Malcolm seems to have been this, having close friends who were Templars and leaving such an impression that even after 25 years, Tobrius is instantly able to recognise Malcolm's children.

In Mark of the Assassin, Areida subtly implies that Malcolm was one of the few with whom the Chasind would barter when coming to Lothering in order to trade, always treating the Hawke family with honour, despite the fact that many Fereldans consider the Chasind to be "barbarians".

Multiple-Choice Past:

Leandra tells her daughters that Malcolm was a Junior Enchanter in the Kirkwall Circle. However, a codex entry says he was a mercenary who was only in Kirkwall on an assignment.

Another possibility is that he either claimed to be a mercenary during his early courtship to Leandra, or the tales of his mercenary past were entertaining stories he made up to tell his children, since he didn't want them going to the Circle.

Or, finally, it's possible that both are true. It's possible that Malcolm was in the Circle, escaped, became a mercenary, came to Kirkwall for an assignment, met Leandra, fell in love, and then they ran away together and eventually built a new life in Lothering.

Mysterious Past: We know nothing about his life before he met Leandra, besides that he was a Circle Mage once. He refused to even speak about it to his wife or children. Legacy reveals that early in his relationship with Leandra, he was coerced into briefly working with the Grey Wardens, which he kept secret for a very good reason.

Odd Friendship: With Ser Maurevar Carver. Friendship between a Templar and an apostate.

Forbidden Friendship: Strongly implied. They had to send letters to each other through Tobrius to prevent the Templar Order from finding out.

The Paragon: Just like his eldest daughter, Malcom was a selfless, caring person who always put the needs of others first. His benevolent personality was the reason why Leandra fell in love with him.

Anders: “What was your father like?”

Areida: “A good man, patient. He never yelled, but you knew when he was disappointed.“

Parental Favoritism: Not maliciously, but Legacy reveals that he had the closest relationship with his youngest daughter, Bethany, due to training her with her magic.

Posthumous Character: He's dead by the time Areida Hawke's story begins, but his presence is felt throughout.

Precursor Heroes: Especially in Legacy, which involves his daughters carrying on the work he left behind.

Pro-Human Transhuman: Though born with incredible powers, Malcolm avoided trying to be like the Tevinter-esque mages, who viewed their magic as a privilege to be abused and used their power to oppress and lord over their fellow people. Instead, he spent his life trying to be a decent and moral human being, and he tried to teach his magically-talented daughter, Bethany to be responsible in the mastery of her abilities.

Retired Badass: After settling in Lothering.

So Proud of You: In Legacy, Malcolm gives a posthumous one through Bethany. He naturally had to spend a lot more time with his only mage child, but she tells Areida that he was still deeply proud of "his little scoundrel and his little soldier."

What Beautiful Eyes!: Malcom had striking blue eyes that a lot people found attractive.

What If the Baby Is Like Me?:

Malcolm did not want his children to have magic, lest they take on the burden he has dealt with his entire life. It happens at least once with Bethany.

To the man's credit, his daughters are quite surprised to find out he did not want a child with magic, and imply that he never let this interfere in raising them. He and Bethany especially were very close.

What Happened to the Mouse?: It's implied that he bound four demons in the past, yet Areida only fight three of them.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

ok. I finished Children of God (sequel to The Sparrow), and while I was able to follow it better than when I first read it (I think I was really distracted a few years ago, and had trouble focusing).....I didn’t like it as much as the first one, which I’m aware isn’t an unpopular opinion, even though I didn’t hate all of it. Here are my thoughts on why it didnt work imo and what I did like about it.

The Sparrow would naturally be a hard act to follow, and I get that sometimes sequels do different things than the first installations. book one is about Emilio and book two is about Rakhat. Okay. I think there’s a lot of interesting material that could have been made of Emilio, John, and all the new guys visiting Rakhat years after the first expedition. It’s what the author did- and, really, this was present in the first book as well, and one of the first book’s issues, but here it’s really one of the main points of the story and far more prominent than ever before- that didn’t succeed. It’s the story of Rakhat....but given how Rakhat is written, maybe it shouldnt have been. This book honestly ranged from “enjoyable” to “disappointing” to “implicitly or explicitly expressing horrible views”.

It’s one thing to make an oppression storyline in a fantasy setting- FMA for example does this. But in that, the victims are humans. In this, not only does the story do an oppression narrative about fantasy creatures, which is already a very difficult thing to pull off, she repeatedly draws comparisons between nonhuman aliens and things like the Holocaust and genocide and oppression of Native Americans. She even has her one native character draw this comparison and *stay behind on another planet instead of going to earth* for some “reservation” plotline at the end. This is a good example of why when we criticize media sometimes we have to focus specifically on the writers who choose to make these events happen, who choose to write certain stories and who choose to frame them in certain ways. I’m kind of glad this book doesn’t have a fandom, really, because tumblr types would focus on which aliens’ side is “right” and not on the fact that the author chose to write some fantasy creature oppression story with incoherent imperialism commentary while trivializing real genocides. I remember a really uncomfortable paragraph in the first one that implied the Ottoman Empire was some kind of safe haven for all ethnic/religious groups as well as a line (keep in mind these were written in the 90s) about how Bosnia is violent because of ............ “blood feuds”. Many people have said this story is weak because it focused on these new alien characters and the Rakhat storyline so much. This, for me, is the main reason why that storyline was so weak.

One thing I liked was some of the new characters. I liked Danny and Joseba and Nico and Sean and Gina and Pope Gelasius. I think this book kind of did a “later season of Vikings” so that there were suddenly all these new people but few of them got good development. So that was a weakness but I didn’t mind many of the characters in and of themselves and enjoyed these new additions. Sure they weren’t like the people in the first book but that’s okay. They added new perspectives. Danny had a lot of interesting stuff about forgiveness that I liked. I also liked initially how Sofia was revealed to be alive but....she was shafted. We barely see her in favor of her badly offensively written written son (I know this was written 20 years ago but. the way he and his disability are portrayed as like...literally “alien” even though ths is supposed to be a “positive”.... is honestly....why the living fuck did she do this....) and Supaari’s daughter who he CONCEIVED FROM RAPE and we’re just supposed to be ok with that bc the author very conveniently wrote the victim to be as unsympathetic as possible and because “uwu miracle of life!! yay children!” I’m supposed to buy that Sofia, a child trafficking survivor, is allies and friends with a man who not only is a rapist but sold a person she loved into sex slavery.......after the narrative called to attention how similar Sofia and Emilio’s experiences were, and the first book was an imperfect story but a deep introspective exploration of the effects of SA.....lol ok. And then she gets killed off at the end offscreen in a single sentence.

There’s also....I really doubt she intended some of this but it’s clearly in the story .... it really has bad implications, that the only relations between men are abusive in both books. there are literally no other relations between men, even though there is a gay character (who I understand is a celibate priest, and having a gay priest is cool!) but....it just doesnt have good implications that relations between men are only ever presented as bad. especially because the thing that truly “heals” Emilio is being with a woman and I think in our society (and thus our media) we have a real problem with thinking that “healing” as a sexual abuse victim means having sex with a man if youre a woman and with a woman if you’re a man, and that male sa victims of men are only really victims if they like women (and, of course, women sa victims in general just have to like men). Of course there is nothing wrong with Gina, I loved her, and nothing is wrong with writing an sa survivor who is able to have a relationship after. But MDR killed her off for no good reason. The other crew members dying in the first book, those were well written character deaths. and how many times did she do the “this woman died but thats whatever narratively, because she has a kid uwu miracle of life” thing in this sequel. I think MDR is like GRRM in that she has good intentions clearly, and has such good sff works/characters and takes oh the Human Experience and everything, but doesn’t always know how to handle issues in a responsible way and it’s really glaring even if there are obviously worse people in media. To be honest (and again, here Im glad there’s no fandom, because people are so weird about this stuff) MDR should have just had Emilio and John be together. “Your friendship should have been proof enough of God” ???????? hello?????? Their relationship was one of the things that actually was well fleshed out in the sequel until John and all the other guys who weren’t in the Camorra just.....stayed on Rakhat forever.

Part of the handling of Sofia seemed like a broader pattern of the plot being completely forced. Everything happens for some sake of The Plot- this is something later seasons of GOT have been criticized for. This plot in particular, in addition to the alien oppression metaphor, seemed to want to make everything about the story in particular its end be some kind of “bookend” to mirror the first book. Sofia dies (for real this time. honestly....her death in the first one was good writing!), Emilio and his unlikely escorts go home, no one else gets to go home, there’s a huge societal upheaval on Rakhat because of the humans, a huge reveal about Rakhat’s “divine” music. I have nothing against this kind of narrative device but when it’s this forced to the point where the story is blatantly constructed for the sake of this......it didn’t work. The “music” plot twist was like..............really??? All of that? They’re staying on this planet? If they had all gotten more time in the story (because this book is the same length as the first book but has far more different subplots and far longer of a timespan and far more narrators) we might find that more plausible. I don’t think everything needs to be spelled out for us. In the first book when everyone is stranded, it’s clear that they think this is tragic, but they are trying to make the best of it because they all love each other and are together. In this one they don’t all have that kind of bond and it’s dependent on the long-winded and incoherent Rakhat political storyline. Because a lot of it isn’t even that well developed in addition to the earlier addressed things. We go between random one-off characters. So much is about the war but it’s written so anti-climatically. Sofia broke down in the first book when she learned they were stranded, and now she doesn’t care at all about returning back to Earth because the Runa are “her people” now, but how much of that is really what she tells herself to cope with what she lost- and what she experienced on earth in her youth? we don’t know. The Pope just....sent Emilio who became probably the most infamous person on Earth, back into space, and it wasn’t a big deal for the Church or at all? And all it took for it to happen was a handful of Camorra men with Vatican connections, who were just adapted so well to space travel and extended time on a new planet that initially made the people in the first book sick when transitioning into life there? And let me reiterate we’re supposed to accept that the divinely ordained reason all this happened was because Isaac wrote music inspired by human and alien dna and it sounded wonderful?

This just felt very forced. “Emilio never wants to go back to Rakhat so obviously this book has to be about how he goes back there and accepts that it actually happened for a Good Reason bc of some music, and music was the way they found it in the first place.” How about how he accepts that it happened and comes to terms with what happened to him without either hating himself for his actions or thinking it was all For The Greater Good Actually, because you cant undo the past, aka what the first book was building up to and culminated in? idk. the first book was all about how bad things happen and that this doesn’t mean we have to give up our faith even if we question our faith. this was more like “every cloud has a silver lining lol”.

There were many nice things- Emilio’s friendship with Nico, many of the moments with Sofia towards the end and her reuniting with Emilio, John getting more to do, the new Pope, Celestina ending up having an important job as a theater and leaving a trail of men in her wake lol. I don’t want to say don’t read this. But if you like the first book you might not like this one, and if you’re considering reading the first book, it.....works best as a standalone.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hyperallergic: I Am Not Your Negress: On Violence and American Necrophilia

James Baldwin in I Am Not Your Negro, a Magnolia Pictures release (photo courtesy Magnolia Pictures, © Dan Budnik, all rights reserved)

Written on the birthdays of those enduring women: Toni Morrison, still on this side, and Audre Lorde, loving us from the other.

I did not read the reviews, because I had not seen it yet. I had planned to read them after I saw it. By all accounts, the film was riveting, moving, good, and all of that. An important comment on race and national history in the era of Black Lives Matter. A beautiful articulation of those genius words of that genius Baldwin, wrapped appropriately in the prescience and urgency of their prophesy. A mirror to America, to who we really are, to our individual and collective responsibility. A painful but loving, optimistic look. A good, important film that everyone should see.

Raoul Peck’s documentary I Am Not Your Negro opens with an implicit promise to pick up where Baldwin left off, to revisit the last book Baldwin had been writing but did not finish, which was to be about his friends, Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr., and their assassinations. This, of course, is a difficult promise for a documentary to fulfill, despite the fact that Baldwin’s prophecies about race in America feel perhaps closer and truer than ever. After all, it was said that Ralph Ellison’s Juneteenth, comprised of chunks of an unfinished manuscript edited together by his literary executor John Callahan, was the writer’s words but not his novel. And we all know not to watch the “Lost Episodes” of Chappelle’s Show.

After seeing it, I read the widely circulated A.O. Scott New York Times review of the film, which, perhaps unintentionally, conflates the lushness and poignancy of Baldwin with the documentary that draws on and flanks his words. I noticed the customary film information at the bottom of the review, run-time, director, and the like. And the rating:

I Am Not Your Negro Rated PG-13 for racial slurs and implied violence.

I wondered how such a spectacularly and explicitly violent film — punctuated by the nude body of Malcolm X, pictured from the shoulder up with the giant’s mouth agape at the very beginning of the film; casket photos of Medgar, Malcolm, and Martin; photos of lynched bodies, their snapped necks and foaming mouths in clear view; grinning, vile, white mobs heaving, lynching, shoving, stopping the Communist plot of desegregation; police batons rising, falling, and cracking onto black bodies without ceasing; an indigenous woman, stripped naked by white soldiers, her breasts bare; an officer getting a running start to shove a nameless black woman to the ground; an extended look at the LAPD beating of Rodney King — might be described as having “implied” violence. The film jerks the audience on a necrophiliac roller coaster, plunging us into the serenely violent whiteness of classic Technicolor musicals and then jerking us back to Mantan Moreland. Pulling us down into the assuredness of Baldwin’s words, then unsettling us with police beating a black person. Some of these images of violence are from documentaries, some from films, some from photographs, some from real life. How are we to distinguish one from the other these days as we are so inundated? I searched for the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) explanation to understand more:

Rated PG-13 for disturbing violent images, thematic material, language and brief nudity

The MPAA explanation is certainly more accurate for what is depicted in the film, but the description at the end of the Times article is more accurate for how we relate to images of black death today. The violence might be described as implied, and in fact not really mentioned in the Times review at all, because we have become accustomed to visual representations of the murders of black people and their murdered black bodies, real or Hollywood. They are implied because even when captured on video, live on Facebook, no one is guilty of them.

This is the problem with this film and other projects like it (think 12 Years a Slave). White audiences demand proof of their brutality and we give it to them in its rawest, most spectacular, most primitive, most titillating form. Interspersed with Baldwin’s eloquent and exhaustive observations and critiques about race and/in America are these images of spectacular violence. Rather than letting Baldwin speak about sexuality, in the nation as well as his own, the film instead suggests it, in its first few minutes, through a government surveillance record that declared Baldwin “a homosexual.” Through this rhetorical move, Baldwin’s sexuality is shoved in the closet, setting up the audience, and particularly a white male liberal audience, to be quietly, secretly intimate with him in this expansive Narnia of living and dead black men’s bodies that we access through Baldwin’s beautiful wardrobe of words. These images of dead and abused black men’s bodies are almost always juxtaposed with images of enchanting white women, the Doris Days, the Joan Crawfords, dancing about, looking innocent, contemplating, being forlorn, wondering and wandering in their equally spectacular oblivion. The point, of course, is to show that the ease of white life is made possible by black suffering, but it falls into that trap of what cultural studies scholar Tara McPherson has called “lenticular logic” — the idea that black and white experiences, or oppression and supremacy, cannot be represented in the same frame. This point is then buried under the necrophiliac sexualization of black bodies. With killing this shocking, this jarring, this pleasurable, this thrilling, this grotesque, this climactic, who would want it to stop?

* * *

Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and James Baldwin in I Am Not Your Negro, a Magnolia Pictures release (photo courtesy Magnolia Pictures)

In the context of this all-consuming violence and the glossing over of Baldwin’s queerness, I wondered about his dear friend Lorraine Hansberry, the playwright and writer who was also a queer black woman, who appears briefly in the film as an aside of sorts. Against Hansberry, the documentary inflicts a different kind of violence: it silences her, renders her absent. Over the familiar photograph of the smiling writer, Samuel L. Jackson, the film’s narrator, reads Baldwin’s recounting of Hansberry’s conversation with Bobby Kennedy in that famous New York City meeting in which Kennedy was trying to ascertain “what the Negroes wanted.” Hansberry reportedly said to Kennedy, “I am very worried about the state of the civilization which produced that photograph of the white cop standing on that Negro woman’s neck in Birmingham.” The documentary recounts Baldwin’s reflection on the way Hansberry had smiled at Kennedy, a smile perhaps of disappointment and rage and disgust and menace, as she rose to leave. Said Baldwin, “I was glad she was not smiling me.”

While men speak in the film — Martin, Malcolm, Harry Belafonte, Baldwin, Poitier, Kenneth Clark, and so on — we do not hear Lorraine’s voice. Instead, we are provided only with Jackson’s narration of Baldwin’s retelling, itself so far removed from Lorraine’s voice, her importance to Baldwin, and the sanctity and beauty of their queer friendship. And then we learn that Lorraine has died at 34. Of what we are not told. There is no casket shot of Lorraine. No way to consume her death or linger on it or to mourn it. Just her absence.

I always wonder about Lorraine. I have especially wondered about her this year because I am 34, the age she was at the time of her passing. My colleague and I, my best friend from graduate school, my co-author and collaborator, call ourselves James and Lorraine. He says he will not let my end be like Lorraine’s. Or like Zora’s. Sweet, sharp, brilliant, beautiful Lorraine Hansberry.

If we were making a list of demands, I’d want Hansberry to be added to the film’s list, but she would not be. I’d want her name and all of the women’s names to be said aloud. The dead and the dying. The ones beaten, assaulted, lynched, and raped. Say these women’s names first, even, before the litany of men’s names, to mark the intersecting terrors of racism, sexism, and heterosexism at work in those women’s lives and deaths. The film refuses to reckon with the complexity of broad structures of oppression in the same way it refuses to reckon fully with Hansberry, or Baldwin for that matter, beyond their relationship as two black writers.

In its closing bits, the film compels the audience to look directly into the faces of black people, using a series of shots, each several seconds in length, where the subjects look directly into the camera. Even here, most of the documentary’s subjects are men. First, two close shots show black men’s faces looking out at us, followed by one or two shots of black women’s faces, followed by more men. Look at their faces, white folks, the documentary seems to say. Unlike most of the film’s focus on the dead, these black men are living, which means you could go to their neighborhoods and find them and fuck them, but they might die if you don’t do something about the violent racism they face, and then you’d have to fuck them in that other way, but why not have it both ways, as you always have? The documentary also presents a list of the black children slain in the era of Black Lives Matter, their pictures on one side of the screen, their names on the other. Aiyana Stanley-Jones is the lone girl on the list. How many black girls were missing?

(God bless that woman Lillian Smith. She knew.)

Lorraine died of pancreatic cancer. Though epidemiologists and men and white people will not admit this, among black people, and black women in particular, cancer has the same cause as a lynching or a rape. The same kinds of racial violence — the absence of white empathy for black pain, the perception that black people do not experience pain like white people, unequal healthcare quality — are the cause.

How, then, are we to advise white people — because this film is about advising and satisfying white people — about the everyday structural and interpersonal violences they mete out, even when they are not actually stringing us up from the nearest real and actual tree? That their continued ignorance — after all of this black writing and marching and singing and pleading and litigating with them to not be ignorant in a million different ways — is not just annoying but fundamentally violent? Why must I wait to die before they realize they are killing me? I can barely make a living because they are killing me, and my friends; we patch each other up with hugs and kisses and bourbon and chocolate and so, so, so much reassurance that we are right and good and okay and we will prevail for our children. Like our mothers and fathers and aunties and uncles, like Uncle Jimmy Baldwin, who thought they would prevail for us, their children and other kin. Like they did in some ways, but didn’t in others.

We die, by the hundreds, by the gun, the baton, the emotional stress, the trauma, the eviction, the diabetes, the cancer, the rage, the stares, the resentment, the little nervous laughs white folks have when we are still eloquent and joyful and beautiful. They wonder if we hate them and that wonder is heavy on us because it is the worst kind of gaslighting. They ask with their eyes, and sometimes directly, as happened to me recently after a lecture I had given: “Do you hate me for being ignorant to your suffering despite the fact that you have told me of it?” No, I am suffering, and to hate would take too much energy and I am weary. We die from white ignorance. We die from white refusal.

I suppose, perhaps, this is the “implied” violence. The violence that kills us slowly. Upside down car loans and mortgages. Payday loans. Thieving bankers opening up phantom accounts. That violence where we can’t stop the babies from coming and when they come, we can’t have them because we got to take care of the other babies. That violence that turns us against ourselves. That makes us yell at our children when we meant only to say softly that we just didn’t have the money for that activity this week but we would really, really, really like to provide you with that little thing you wanted, baby, because we want you to know you are loved despite what President Agent Orange says. That makes us eat and eat and eat and drink and drink and drink until we vomit and fall asleep on the floor next to that vomit. That makes us mad that we woke up the next morning because we got to clean ourselves up and get out there and face this shit again. I wonder how we might depict that in a documentary to make them know.

These days we call this kind of racial violence implicit bias. I suppose that’s like implied violence. The prospect of being outed as racist is hard for white folks, as though it’d be easier if black people weren’t around (dead, gone to Africa, so forth), so there wouldn’t be anyone to be racist against. But I’m still damned dead and someone is standing over me with a ghoulish smile, shocked but loving.

But I am not your negress. I am my own. And I think that is important to say amid all this clamoring that gawks at, consumes, and possesses black lives and deaths.

I Am Not Your Negro is playing in theaters across the US.

The post I Am Not Your Negress: On Violence and American Necrophilia appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2oIyQ5A via IFTTT

0 notes