#I just really like the social justice spirit warrior thank you send post

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Lukewarm to mid-temperature take about Dragon Age II meta that I found in my drafts from a hundred years ago, but I was still right -

I think Justice was corrupted when he and Anders joined, but it wasn’t anything Anders did that corrupts Justice, eventually; it’s what was done to him, what he lived through. Like, spirits corrupt when they’re acting against their nature, or can’t fulfill their purpose. Two thirds of Anders' life, up until the Wardens, had been an extended injustice. Justice could not handle that shit intact, but when they did the ritual, there wasn’t a choice. So he changed, and lashed out uncontrollably. It’s only by Anders’ will (very literally) and their common ground that Anders doesn’t become a body-horror-activated abomination right there.

This also tracks with how Justice changes in DA2 depending on Hawke’s and Anders' relationship in the friendship / rivalry routes. If you encourage Anders’ views and help him with his cause, reinforce that being kidnapped and brought up in a Circle wasn’t right and he does have the ability to do better, him and Justice work together. You can hear Justice’s tone of phrase come through, and him referencing his memories sometimes, when Anders is talking. But if you rival Anders, tell him the Chantry and templars were right to imprison him, that mages are incurably dangerous, that everything he lived through is (if you’ll forgive the pun) justified-- Justice gets worse. Instead of working with Anders until they share a purpose, he overwrites Anders’ mind & will with his own. The acceptance of injustice makes Vengeance the only possibility. (Stealing a line from one of the only good Frankenstein movies,, if he can’t satisfy one he’ll indulge the other.)

+ Worth Noting, Three: The way that Justice and Anders mix together. I really think that part of Justice’s corruption arc is the others genuinely not recognizing how much of him is there. Like, the whole ‘Justice is righteous. Justice is hard’ line. Justice was very black-and-white with his thinking. Justice also didn’t know what cats were, and he worried about Sir Pounce-A-Lots freedom of person. Justice liked feeling the wind on his face. Justice made a joke about the darkspawn ‘catching Kristoff’ when someone mentioned he'd went to go to catch them. If Justice hadn’t been inhabiting a corpse the first time he realized he’d caused someone grief, he would’ve cried, he wanted so badly to help.

Absolutely, revenge and (yk) judgment were significant parts of him. Justice was also kind. He had humour, and complicated ethical questions he was grappling with.

I think that so much of that got folded into Anders, the only thing that Hawke and the others recognize as different, fully ‘Justice’, was his rage. And that's a huge part of the tragedy of it. But Anders was right, he was there the whole time.

#I just really like the social justice spirit warrior thank you send post#DA2#Dragon Age#Goose's original poster tag#long post#Ask to tag?

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anonymous asked: I really enjoyed your book review of Sebastian Junger’s Homecoming. Perhaps enjoyment isn’t the right word because it brought home some hard truths. Your book review really helped me understand my older brother better when I think back on how he came home from the war in Afghanistan after serving with the Paras and had medals pinned up the yin yang. It was hard on everyone in the family, especially for him and his wife and young kids. He has found it hard going. Thanks for sharing your own thoughts as a combat veteran from that war. Even if you’re a toff you don’t come across as a typical Oxbridge poncey Rupert! As you’re a classicist and historian how did ancient soldiers deal with PTSD? Did the Greeks and Roman soldiers even suffer from it like our fighting boys and girls do? Is PTSD just a modern thing?

See previous post for Part 1. Part 2 of my answer here below....

But does it mean no Greek or Roman soldier ever suffered trauma or mental illness? Is there nothing we can’t learn from them? Of course not. Both the Greeks and Romans can teach us a lot about suffering.

Both cultures recognised the importance of integrating soldiers back into society that were they had tried to defend on the battlefield. And I think we can learn a lot from them in the regard.

If we are able to accept that PTSD is not a product of mechanised warfare and very likely did occur in ancient societies, then the question should be asked: how did ancient cultures deal with individuals who experienced trauma and suffering? We know that exposure to violence occurred. And we know, too, that homecoming was a common experience, in that some type of military service was a regular feature of the cursus honorum for those in the senatorial class and was an avenue for the lower classes seeking advancement. Valour in combat was respected, and it was not unusual, when in pursuit of higher office or defending oneself at trial, to display one’s scars from battle as a physical witness of character.

Inscriptions inform us that many veterans pursued successful careers upon their return, becoming leading men in their cities. We know that they feared war and respected it, we know that they used ritual to distinguish war from peace, but we do not know how these men fared emotionally and psychologically after long exposure to violence.

While many ancient cultures were able to recognise the significant changes in soldiers following a battle, the precise reasons as to what created these changes were elusive. A common explanation was that the occurrence of (what I describe as) PTSD was caused by the actions of malevolent ghosts or spirits of those who were killed in battle and now sought vengeance on their killer. While it is unlikely that a vengeful spirit explanation is correct, it does contain the insight that the sickness originated from an inward or unseeable wounding, and these invisible wounds could be just as deadly as any outward wound.

Many ancient cultures sought to deal with and create specific rituals to heal the unseeable and drive off the ghosts who caused them. The central purpose of these often culturally unique rituals was to welcome the returning soldier back into society and allow for the release of trauma. The Romans directed the Vestal Virgins to bathe returning soldiers, purging them of the corruption of war.

While the plethora of writings describing PTSD-like signs in ancient veterans indicate that these rituals did not always work, given the sheer numbers of ancient soldiers who went into battle and through these rituals, it would seem likely that for many something about them did work. However, it might not have been the welcome back into society alone that worked.

What might have been even more important, and what is often overlooked, was that the reintegration process would begin in the aftermath of the battle when the survivors began to walk home. Given that ancient soldiers sometimes fought far from their homeland, when the war was over they had to the walk home. The speed of this return was dictated by the pace of the slowest pack animals and the slow pace, while frustrating, may well have given the soldiers much needed time to reflect upon what they had experienced, grieve for comrades lost and perhaps find solace in a shared group experience. The long march back culminated in a ritual cleansing and a return to home, as mentioned above.

One of the reasons this slow decompression might have aided the efficacy of the return rituals can be seen in its complete opposite in contemporary conflict, where the advent of improved transport has made it possible to move troops quickly and efficiently. Perhaps too quickly and too efficiently. While troops might be happy to be back at home far more quickly, there might be a lost opportunity for soldiers to properly process what they have seen and experienced within a like-minded group.

I believe that we must be cautious when we map the past too neatly upon our own experiences or, conversely, our own experiences too neatly upon the past. While there are similarities and continuities, the relationship between ancient and modern must be carefully parsed. All lovers of the classical past are familiar with how the study of the Greeks and Romans awakens profound and contradictory feelings of identification and alienation. With respect to combat trauma, the shock felt by a modern soldier upon seeing a corpse for the first time would have been incomprehensible to both the Greeks and the Romans, who were surrounded by death.

Likewise, modern technology – with its distant, impersonal, and terrifyingly effective weapons, its instantaneous communication between home front and front line, and the speed of return from combat – requires an adaptability and an ability to get one’s head around big spaces and multiple actors that would never have been demanded from a Roman legionary.

My own view is that our soldiers actually face more complicated psychological factors than did the Romans – including a populace that largely avoids the realities of war while still wishing to enjoy the profits of it.

In addition, as our understanding of what causes PTSD grows we may find a paradox: distance weapons, developed to provide overwhelming military superiority and to shield troops from the fear and horror of close combat, may in fact cause more trauma, whether owing to the shockwaves they send through the brain or to the sense of helplessness they engender.

Moreover psychologists believe that modern PTSD cases are the result of the loss of ‘ontological security’ – ‘an individual’s inability to reconcile their traumatic memories with their moral codes, self-concepts, beliefs about human nature and notions of cosmic justice through which they seek to impose what anthropologists call a sense of order and meaning on the world. The psychological conflict arising from trauma ensures that the trauma lives on as ‘a source of socially and psychologically maladaptive behaviour’. But - and here’s the crux of it - the definition of what is a traumatic memory is as variable as the sufferer is individual, and this is culturally dependent even in the most homogenous societies.

Where we can learn from the Greeks and Romans is how they dealt with homecoming and using religious spirituality to balm emotional wounds.

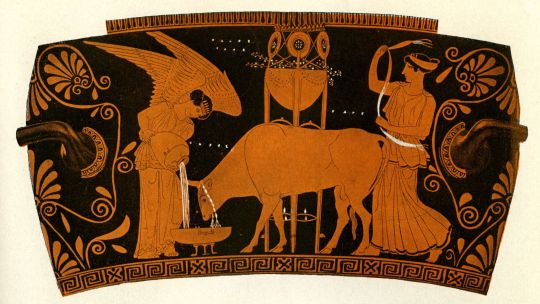

For the Greek warrior, Classical Greek culture, like that of Rome after them, practiced polytheism, the expression of which included confirmatory and transformatory rituals. Ritual purification with water occurred in Greek funeral rites, with indication that pollution associated itself suggest that the cleansing had anything to do with establishing proper relationship to the gods, but may have had a purely “practical” force.

A more important spiritual concept to the Greek soldier than that of pollution may have been that of the necessary separation between the warrior’s life and the domestic life. In ancient and classical Greece, city walls held a religious significance as the separation between the sacred and the profane, for inside the walls are the sanctuary and security of domestic peace, while outside the walls warfare and the domestic life from which the warriors of his tale are separated, evoking pathos in the listener; the Iliad’s action describes the soldierly activities and battles of the Greeks and Trojans, while Homer’s metaphors describe the everyday activities which the Greeks have left behind and with living relatives as well as physical location.

Some Classicists believe there is little evidence to suggest that the cleansing had anything to do with establishing proper relationship to the gods, however. Furthermore, a Greek male’s citizenship was based on his membership in his city’s fighting force, his τιμή, honour, was directly related to his performance in the line of duty, and “a purely predatory attitude toward the lives and possessions of one’s enemies was an essential part of archaic and classical Greek warfare. This attitude toward battle makes it unlikely that Greek soldiers would have felt any sense of pollution either from warfare or the soldier’s association with, or proximity to, death or blood; cleansing rites were likely observed for fallen comrades and camps, but may have had a purely “practical” force.

A more important spiritual concept to the Greek soldier than that of pollution may have been that of the necessary separation between the warrior’s life and the domestic life. In ancient and classical Greece, city walls held a religious significance as the separation between the sacred and the profane, for inside the walls are the sanctuary and security of domestic peace, while outside the walls exists the world in which warfare and strife takes place.

In the Iliad, Homer makes extensive use of metaphor to juxtapose the world of warfare and the domestic life from which the warriors of his tale are separated, evoking pathos in the listener; the Iliad’s action describes the soldierly activities and battles of the Greeks and Trojans, while Homer’s metaphors describe the everyday activities which the Greeks have left behind and been separated from for ten years, such as women sewing and farmers reaping.

The soldier may accumulate honour in battle, but he is acutely aware of what he is sacrificing, even if only temporarily, to gain that honour. Homer’s Odyssey and Aeschylus’ Agamemnon are explorations of difficulties the Greek warrior faced as he attempted to return to domestic life after long absence in war. The concept of such separation may have had a sacred significance akin to the idea of the separation of domestic and non-domestic spaces established by walls; it was at least culturally significant to the Greeks of Homer’s and Aeschylus’ times.

Though Greek soldiers may not have had purification rituals to cleanse themselves after battle, Shay proposes that warriors of certain Greek societies, at least, had a form of transformatory, religiously-significant ritual which served to reintegrate them into domestic society after long separation in mandatory military service and, for most, exposure to combat. He writes, “The performances of Athenian tragic theatre - which was a theatre of combat veterans, by combat veterans, and for combat veterans - offered cultural therapy, including purification...The ancient Athenians had a distinctive therapy of purification, healing, and reintegration of returning soldiers that was undertaken as a whole political community. Sacred theatre was one of its primary means of reintegrating the returning veteran into the social sphere as “citizen.”

Shay proposes that soldiers hearing or reciting the Iliad would also have experienced a similar sacred catharsis; thus, this might have been one reason for the works’ significance in Greek culture.

What of the warrior of Imperial Rome? What of homecoming and religion? Religion was likewise both a public and private affair during Imperial Rome.

Political leaders and military officials were also religious leaders, and the people considered the emperor god-like, if not a god, within one of Rome’s many public cults. Ritual practices were integral to both state and private religion. The Romans accepted that the safety and prosperity of their communities depended upon the gods, whose favour was won and held by correct performance of the full range of cult practices inherited from the past. Bargaining rituals, in which a specific ritual action was performed or promised in return for fulfillment of prayer, as well as confirmatory and transformatory rituals, were common throughout the Roman Empire’s many public and private religious cults.

Within this cultural context, Rome allowed her soldiers to practice in accordance with individual religious beliefs, and the army took part in public religious activities. Among many other state religious rituals, Roman armies underwent ritual purification (known as lustratio exercitus, translating literally as ‘the purification of the army’), sometimes before battle, sometimes after (or sometimes both). This ritual may also have been performed on the Campus Martius (the sacred field dedicated to the Roman god of war, Mars) at the start and end of the military campaign season.

The Roman practice of leading a victorious army under a triumphal arch may also have been a ritual purification; soldiers decorated themselves and their standards for both rituals with laurel, a plant commonly used for purification in other aspects of Roman culture.

Scholars disagree as to the purpose of the purification ritual and the sacred nature of an army’s triumph. Pritchett suggests that Roman generals conducted the lustratio exercitus in order “to remove superstitious dread” from the soldiers before battle. Some scholars argue that the purification ritual was not merely to remove dread before battle, but may have included the use of laurel to “cleanse the army of its bloodshed.” In common with the Greeks, Roman soldiers were unlikely to attach any moral disapprobation to the act of killing itself, or find war immoral. But the performance of the ritual after battle and at the close of the warrior’s season indicate the Romans may have felt that some incidental, religious pollution attached itself to the army or the soldier from nearness to death or blood.

As some point out, Virgil in his imperial epic poem, The Aeneid, supports the idea that the imperial Romans saw some impurity associated with the individual’s presence in combat - Aeneas, having just taken part in battle, states that he must purify himself before approaching his household gods. Others sees the act of battle as a sacred undertaking; therefore, at the end of the campaign season, the soldiers ritually desacralised themselves and also cleansing themselves for their acts of violence in battle.

This idea further suggests a sacred distinction between the warrior and the non-warrior, as the warrior undertook a particular religious duty by fighting which the non-warrior did not. The ceremony performed at a Roman soldier’s retirement, when the emperor, or his proxy, would perform a ritual releasing the soldier from the religious oath he took upon joining the army, transitioning him back into private life, seems to suggest this as well.

These ritual purifications may also have marked the transition for the soldier from chaos back to order. Roman society placed high value on order and Rome’s citizens saw the empire as a civilizing force against the barbaric chaos of other peoples; for them, Roman conquest brought law public order, and structure to uncivilized barbarians as much as it did land and treasure to Rome.

The division between what was civilised (Rome) and was chaotic (barbarians, and thus anyone Rome was at war with) was sacred and sharp, and it was the Roman army which crossed that line to carry order to the peoples of the world. The presence of the ritual after battle and after the campaign season may mark a restorative or transitional moment in which the soldier’s association with chaos in battle against an uncivilized enemy ends and he returns to the orderly world of Roman civilisation.

While no absolute solution can be drawn from the experiences of ancient soldiers, there may be sufficient clues to warrant studying what benefits might be gained from delaying the return of groups of individuals from conflicts in a structured manner, thereby lessening the propensity for PTSD to occur. Particularly, if it were possible to enact rituals of our own - rituals which recognise and free returning soldiers from their traumas and assuage any sense of guilt and culpability - and reinforce that society values them for what they did, we may be better able to deal with PTSD.

Indeed whatever the causes or effects of PTSD suffered by returning service personnel, homecoming is crucial to integrating that person back into his/her family, community, and society. Earlier I talked about research done on British, European and American returning soldiers and the wide discrepancies between the European and the American experience of dealing with PTSD and reintegration.

I think one reason why British soldiers fared better than our American brethren is we had more effective mental health tools and mechanisms in place. I’m sure your brother as he was with the Parachute regiment would have gone through the TRiMS and TLD programme as a way for returning British soldiers to process their tour experience before being allowed back into the fold. It doesn’t work for everyone but certainly catches more in the supportive net who otherwise might have profound difficulties ‘coming home’.

For those who don’t know since 2007 the British armed services have been using the Trauma Risk Management program (TRiM) and the practice of soldiers spending time in a “third location decompression” (TLD) to help the process of homecoming as well as detect early warnings of PTSD. Both have been important tools for British soldiers to process their emotions and experiences.

The good thing about TRiM is that it’s a peer support system designed to assess trauma experienced by soldiers and encourage them to seek help if needed. TLD requires its participants to spend 36 hours in a location away from combat before returning home, often on the bases in Cyprus within the British Sovereign Territory there. Both of these mitigation measures focus on unit or regimental cohesiveness, which is has been well proven to be associated with lower levels of common mental disorders and PTSD. The aim of decompression is to ensure everyone gets a proper mental health briefing and that they are able to speak informally to each other without being judged. In the end it’s an invaluable opportunity to access the social support needed and begin the reintroduction to ‘normal life’.

Of course no system is perfect - look how sprawling the British veteran charities are for instance (Royal British Legion, Poppy Scotland, Combat Stress, Connect Assist, the Ministry of Defence, SSAFA etc) with over 2000 registered veteran charities which leads to confusion about services and support. No measure that is put in place can treat every single soldier but every little bit helps more than it hinders a soldier’s return ‘home’.

In the end to wheel back to your question, the issue of whether the Romans suffered PTSD is probably unanswerable, because the problem itself exposes many of the challenges posed by the historical study of the past. I do know that the view that the Graeco-Roman world knew PTSD is fast becoming dogma because of popular culture and trendy lefty academic fads in English departments. I find that troubling speaking as both a combat veteran and as a Classicist.

In this debate of nature versus nurture it can hardly be reasonable to conclude that a legionary would have experienced trauma in the same way as a modern day combat veteran – surely his vastly different upbringing, cultural background and combat experience would have resulted in a culturally unique variant of response to that trauma? So to state that the legionary *must* have suffered PTSD seems simplistic and poorly evidenced. Saying a Greek or Roman soldier’s exposure to close combat and the fact that war is hell wherever and whenever it is fought is not enough. Some men would undoubtedly have experienced trauma induced psychological disorder but what that response was, its nature, causes, symptoms, is simply impossible to know, given the current paucity of relevant sources.

Perhaps when we understand PTSD better we’ll have an ability to interpret that thin evidence and put it into a cultural and medical frame of reference - despite wildly different causal factors and conditioning to meet the unique stressors in each of the ancient and modern soldier’s experience of warfare - that will get us close to a definitive answer. Indeed, as we learn more about concussive brain injuries and slowly unravel the various causes of PTSD, I suspect that we may find the evidence will point to a lower frequency of PTSD in the ancient world than that experienced by our troops in the present day. Until then, to be honest, it’s a game of grim conjecture.

If your brother needs more help please DM me and we can discuss ways in which we can help him find the right fit. You already know about the paras own charity for its veterans, Support Our Paras, so nothing I can add there that you don’t already know. My one recommendation would be to reach out to ex-Para and UK SFSG (special forces operator), Dave Radband. Radders is good egg and has used social media to become an outstanding mental health advocate for ex-British veterans.

Once again my apologies for the long answer in two parts but it’s an issue that’s very close to my heart when I think of my own fortunate homecoming from war and I remember those who didn’t come home...and those still fighting the war after they come home.

Thanks for your question.

#question#ask#PTSD#war#rome#greece#antiquity#spartan hoplite#roman legionary#soldier#depression#mental health#warfare#ancient warfare#shell shock#killing#culture#society#classical#mental illness#homecoming#british#british army

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

(( I done gone got tagged!! Thank you @archbishopandrei ))

B A S I C S

Full name: Dragon. Currently goes by the nickname ‘Grandpa’, or one of the myriad of many and changing titles that have stuck over the centuries. While he has no memory of the name his mortal parents gave him, he is fairly sure he cast it aside long before he was reborn as Kindred anyway.

Gender: Fluid. Non-Binary.

Sexuality: Ace/Aro

Pronouns: Broadly He/him at present. Accepting of any spoken with sincere respect.

O T H E R S

Family: His Beloved Menagerie. Some sense of family extends to a few of the Kine holdings that have leave to live on his Domain; it is hard not to get attached when you shelter so many generations of them, even if most don’t know you as more than an old superstition. No Childer. Hasn’t heard of his Sire in centuries. Does not care to. Also, Kel is is grandson now.

Birthplace: Somewhere in ‘The Old Country’ is the best he can manage to recall. Somewhere by the ocean? He remembers the sound of waves, the taste of salt, the low roar of the wind like the lullaby of something ancient.

Job (Current): Tender of his Domain. Recluse from much of Kindred society as a whole. Other local Elders who know about him are content to leave him be; they would rather the balaur that broods it’s hoard than the wandering kulshedra, all things considered.

Job (Former): Sometimes, if you have destroyed enough of your adversaries, people will say you were a fearsome warrior. Are the flames at war with the forest? Is the flood at war with the plain? Does the storm battle the mountaintop? He was an architect. His designs were for the truth of his soul.

Guilty pleasures: Guilt in pleasure is a worm inside the pear. Spit it out. He doesn’t have time to be guilty over any thing that he enjoys. He shed that skin long ago.

Hobbies: Cultivating his Menagerie, Koldunism and Taking An Interest are less hobbies than they are a purpose ...cooking via all three though? Hm! His principal hobby is is probably sharing in whatever number of hobbies are being enjoyed by his Menagerie at any given time; be it brewing distilled spirits from the local berries or cheering them on as they finally realise their zulo form and romp off to terrorise some hikers.

M O R A L S

Morality alignment: Lawful Evil, your actual Evil acts mileage my vary.

Sins: Desire / Despair / Envy / Fear / Hunger / Pride / Rage / Sloth

Virtues: Charity / Chastity / Diligence / Humility / Justice / Kindness / Patience

T H I S - O R - T H A T

introvert/extrovert

organized/disorganized

close minded/open-minded

calm/anxious

disagreeable/agreeable

cautious/reckless

patient/impatient

outspoken/reserved- Old Koldun Yells At Cloud

leader/follower

empathetic/unemphatic

optimistic/pessimistic

traditional/modern - Curious of modernity, yet unlikely to change his ways.

hard-working/lazy - Spending years at a time in a cocoon doesn’t count, when you’re his age.

R E L A T I O N S H I P S

OTP (canon characters): Nope.

(non-canon characters): Nope.

acceptable ships (canon characters): Nope.

(non-canon characters): Nope.

OT3: Nope. The only valid ships for Grandpa are the ones his Menagerie builds to go boating about on his lakes.

brotp (canon characters): Does not leave his domain enough to form brotp. Is very rusty when it comes to brotp. Would thumbs-up Vykos from across the room, wave in an encouraging manner.

(non-canon characters): There is nobody he is presently familiar enough with, or whom he considers to be on enough equal standing with, to be totally bro unto. Gosh, all these Kindred are so young?? he thinks. That said, there are plenty of characters he finds himself either endeared to or politely in respect of. Ieuan is a Fine Young Tzimisce with A Lot Of Promise. Andrei is a Dedicated Gentleman from the old country who Takes Good Care Of His Meatball Monsters. There is an Archbishop that has spider revenants and he can really Respect That. A nice young Toreador just send him a picture of a dragon crying over cabbages and it was great? Someone posts very interesting articles in which he does not understand half the context of but enjoys regardless. Someone passionately ghouls as many cats a possible and, honestly, that’s a mood. Gosh, he wishes he was better with names. He enjoys meeting new Kindred this way; he gets to be social without anyone ever setting foot on his dirt to facilitate it.

NOTP: Like many other Tzimisce, he will throw literally any Tremere if given but a moment of chance.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

what do you want me to say.

tw: mention of suicide and slurs

I started making videos related to social justice because of a video I saw circulating at the time. It was of a little girl who couldn’t have been more than 4 years old, crying to her mother because she thought that being black made her ugly. This really resonated with me. I grew up thinking that the color of my skin was something holding me back from being anywhere near beautiful, let alone to just be accepted in some instances. This was because of personal situations and instances that had happened to me over the course of my childhood.

Seeing the video at the time that I did, having grown up and gotten over many of those horrible internalized racist thoughts, that video broke me. I couldn’t stop crying about it, because that little girl was me. That little girl was millions of people who have experienced that pain and isolation that she was feeling as young as a toddler. I wanted to do something. I was becoming more confident in myself and my identity, and I wanted to help other people gain that confidence as well. I wanted to make sure no child ever cried again because of their identity.

I loved making videos on these topics. It generated great feedback and discussions from people watching my videos, and outside of my channel in particular, it was a jumping point for many conversations with friends. It was helping to further the much needed discussion on topics such as race, ethnicity, and sexuality. I, of course, made mistakes at times, as we all do, and I tried my hardest to rectify them as best as you can for youtube videos (usually by adding notes in the description correcting mistakes I made and crediting those who had taught me that what I was saying was misinformed). I really appreciated those who were correcting and informing me because they were doing for me what I was trying to do for everyone else. They were doing their part to make sure that everyone would be as safe and comfortable in that space as possible.

Purely based off of what I’ve seen on youtube recently, I feel like the ‘hate videos’ came almost later than expected. I feel as though the only reason they took so long was because I wasn’t popular and didn’t dedicated the entirety of my channel towards social justice (also my system for tagging videos was atrocious). There were a few comments here and there that were offensive, but they were so few and far between that most of the time I could laugh them off.

It was only when I made a video with my friend, my beautiful, talented, amazing, educated, strong friend, Riley, that those other people started to take notice. I want to state this as clearly as I can: I am in no way shape or form putting any blame whatsoever on Riley for any of this, and I absolutely never will. I have so much respect for her and what she does, on youtube and elsewhere, and I am always blown away by the power and impact she has. And after the mental toll all of this took on me, my respect for her has done nothing but increase- she deals with situations like this all the time, and yet she still stays strong and fights the good fight. I wish I had her strength.

So because of the amazing creator Riley is, she has a much larger following than me, which of course meant our video would expose me to more people who had no idea I existed. And they took this upon themselves as a new opportunity to destroy the spirit of someone trying to make a positive difference (essentially, an opportunity to tear me to shreds).

I could write many posts on my feelings about this, and I probably will eventually. But right now I want to focus on what exactly these people want. The ones who specialize in ripping a video, creating their own video from it pointing out every flaw, every word, every single instance they possibly can, and using that to discredit the original person and their ideas. The ones who use their skills of editing to not create their own content; their ability to film themselves not to make something original, but instead use their time, energy, and skill set to laugh at and mock someone expressing their struggles in the hopes of reaching an understanding. The ones who are apparently so passionate about saying how wrong we are for our ‘feminazi views’ that they’ll go to the length of harassing creators on various platforms, but are too scared to post a picture of themselves and will hide behind usernames and empty profile pictures.

I want to know what you want out of this. I want to know what result you’re looking for. I want to know your goals.

Do you want me to find your video? Do you want me to watch it and feel a sinking feeling in my chest? Do you want me to comment, ‘you know what, you’re right, I am confused about my identity. you, a stranger, know more about me than I do’?

Do you want me to thank you? Do you want me to look you in the eyes, shake your hand, and say ‘thank you for showing me I am a stupid social justice warrior, you were right, I’m much happier feeling the abuse you sent my way, not only from your video, but from the hundreds of others that because of your video, now send me daily harassment. it’s all thanks to you’?

Do you want me to do what you tell me to in your videos? Is it as simple as changing my hair, my voice, my face, my attitude, my passion? Is it as simple as following your instructions? As simple as listening to your comments? Do I, in fact, have to ‘kill myself u racist n*gger f*ggot’ for you to get what you want? Is that it? Do you want to see the light leave my eyes? Is that what it’s going to take?

And for what, exactly? What is your goal? Sure, you could very much argue the same for the people you’re making these videos about, but I already know what their answer would be- they’re trying to do what I did. They’re trying to make sure no one feels that pain, isolation, fear, or hurt, just because of the way they were born; the way they identify. They’re trying to make the world a better place, even if it is in the smallest way. They’re trying to make people feel good.

So what exactly do you want here? What do you want to get from all of this? What do you want me to say?

4 notes

·

View notes