#I guess it comes down to how much they’re focusing on personality versus more technical stuff

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

“group interview” occurred. not sure how it went really but I guess that tends to be how these things go

#I guess we’ll see if I’m called back. whenever that may or may not happen#pro: I definitely feel like I was more sociable and interesting than the other two there. plus I have way more predisposed enthusiasm#about the bar itself- I don’t think the other two had even been there before really and I came in wearing a shirt that’s literally merch#hopefully I didn’t sound/look like I was pandering TOO much but. who knows#con: I definitely have less bar experience than the other two#I didn’t get to flex my references beyond Where I currently work (which is still a plus but idk to what extent)#cause I didn’t want to plead in the middle of this thing like. just so you know the chef (who knows the bar owner closely) loves me. you#should ask the chef how good an employee I am. trust the chef he’d say my work ethic is incredible trust me#but yeah#I’m most worried I think about my minimal bar experience and schedule fuckery#I guess it comes down to how much they’re focusing on personality versus more technical stuff#yeah I. definitely think I stood out but it’s hard to say whether that’s good or not or how good or. what#I also definitely talked more and less concisely than the other two. again for better or for worse#ghsghhshhsghhw I don’t knooowwwwwww I just wish I could have people vouch for me who are tied to this bar and stuff#the worst part of interviewing for jobs is absolutely the fucking Waiting period. like. augshghh I hate the anxiety of it I hate it so much#kibumblabs

1 note

·

View note

Note

It Gets You Coming and Going: Of all moral dilemmas, what's one that truly stumps you and why? {ginglymostoma cirratum}

Questionable Quotes || Accepting The question is posed in so very Anakin a way that it almost hurts for simply existing. There’s layers built up between the syllables that only someone who knows him well enough can pick out, and only the very rare amongst them that can tell you where they came from. The deepest is the bedrock of his anxiety, that deep down he believes himself so unworthy that it’s compressed down into the core of him and become the basic foundation of the rest of his personality. Closer to the surface is the silt of fear that he’s said the wrong thing and has reached the tether of her seemingly infinite patience with him. That she’s finally going to snap and savage him with tooth and claw, glutting on the softness of his emotional state until all that is left is something that once resembled the bones of his resolve. And she knows she’s mixing metaphors here but that’s how she conceptualises the things about Anakin she can’t pin to a board and press under glass. Not that she would ever do that, she finds it horrifying and cruel, especially when not that proverbially long ago collectors would do that to living specimens, murdering them with chloroform. Ether. She keeps from curling her lip.

And maybe for those few precious seconds when she can feel his gaze sliding off her and back to the edge of the water, so extremely uncomfortable in his own skin, she empathises with him. Finds it easier to make this about wanting to view himself through the prismatic lens he’s made of her, where every fractured splinter can be compared to the raw emptiness that sometimes fills his own mind and pushes everything out of the way. So he can lose himself in his perceptions ~and she can tell, so easily, when he is sinking in the stream of Time, which is almost always~ and escape for just a little while from the weight of everything resting on too fragile shoulders.

It’s entirely possible, too, and dangerously so that she interprets a good many of their conversations this way, focuses the spotlight on Anakin rather than herself because the idea of introspection makes her a little queasy. That she herself hides behind all the preconceived notions that people have of her that she twists and bends herself to fit into because without them she would be as shapeless as the infinite void of the darkness that lingers at the very edge of the Horizon in the deepest umbral reaches.

And of course she would also never admit to maybe spending too much time dwelling on the reasons why the question wounds her as a means of putting emotional distance and actual thought far out of the way ~out of sight, out of mine. Because it is not the easiest thing to answer. In fact she isn’t sure there’s one that would capture intent as much as interpretation.

The problem with morality as it would be defined by most people is that it is an arbitrary system. An socio-artificial construct that puts a distinction between right and wrong, or good and bad behaviour. And much like consensual reality, the guidelines of such behaviour are dictated by people. And all people are fallible. Even the Holy Father, though he’s not supposed to be.

There are other factors to consider as well. Does he mean specifically as the question relates to Sleepers? Does he mean as it relates to the Awakened as they, master and apprentice, are? If they are speaking about the masses, then are there certain cultural borders they’re straying across? What is good for one group of society is clearly not very often understood by others and so what might be wrong or atrocious in belief may have mitigating circumstances if viewed outside of one’s own group. Then of course there’s the difference between an individual's moral dilemmas and ethical ones, which are similar but still vastly different. Not unlike the Traditions versus the Technocratic Union. And this is obviously not what Anakin means because he’s never seen the heated debates that often took a twist at the dinner table between herself and her brothers.

She wants to tell him, that of course, there’s all of these factors to be taken into consideration. Wants to ask him what he means ~specifically~ in regards to whose morals are being questioned and she knows too that by doing so she will somehow manage to trample his self-worth because he’ll judge himself as not having spoken clearly enough, slowly or carefully enough. That he did not adequately set up the scenario and thus given her something incomplete to work with. There will come a stunning display of beautiful if heartbreaking physical manifestations of that internal grief and she might actually expire from the grief of it all. And she isn’t being nasty about it, she isn’t mocking him in that breath of silence as she considers all of this. It is something that she’s come to experience in the almost year that they have spent bound together by practice and...funnily enough...tradition. And she likes to think she knows Anakin this well by now, that however hard he tries to hide it, she will see.

She reaches into the bucket beside her and takes a hold of another chunk of meat and tosses it out across the murky water. It lands with a specific and yet sad little plop before disappearing below the surface. She watches the way his cigarette smoke rises up to wreathe around his curls a little wild tousled today. It’s a little ironic that she could see him as a dragon, and maybe there’s some Mokolé blood in his family tree, as much as there is shark in hers. But he’s still reserved enough that he doesn’t stick his converse down over the side of the decrepit little dock they’re on. To be fair, his legs are far longer, far too close to the dark, algae choked surface. He’s never had his calf nearly torn right off the bone and probably doesn’t need that experience. Not with his hand in the state it’s in, the way cold and weariness make his bones and joints ache with nothing to compensate for it.

And that’s the point where she realises that now she’s just stalling, letting herself drift along the paths of thought, further and further away from the question asked. So she breathes out a sigh and allows a soft curve settle to her lips that is neither exactly a smile or even a smaller grin. It’s something along the lines of patience made manifest, her natural inclination toward indulging Anakin, and it’s also...tired. The kind of thing that appears when she’s worked herself to the bone and hasn’t slept for days but continues to push herself until she’s at the exact point of inevitable collapse. And how often does she do that more and more these days. Doesn’t even try to make it to her room when he’s just as comfortable as his bed and far warmer even if it’s a slightly unhealthy symptom of his body’s attempt to keep his extremities in life-giving blood. She leans back, wiggling her toes out in front of her, though her legs are still covered by the broom-skirt she’s wearing, arms bracing herself from behind, slick and red, sure to leave prints she’ll have to clean up before they leave. “I don’ t’ink dis really a fair question, Anakin. I mean... dere’s factors. A precise synt’esis would define culture as a body of ideas; norms, rules, standards, values, an’ beliefs. So dat different cultures would derefore have different moral an’ et’ical impact. An’ mebbe even between one generation an’ anoddah, like dem boomers an’ millennials. I mean, you an’ me are kinda li’dat too, as technically I’m a millennial an’ you’re Gen Z. Between all people dere’s dis enforced, learned social norm dat are symbolically an’ practically reinforced an’ referenced in displays dat signal adherence to any specific system. Now, I know ya no talk story about all kine people, ya specifically aks me ‘bout my own issue an’ I guess...” She trails off trying to regather herself. When she speaks again she does that thing she does when she thinks something is important enough to give him the best chance of understanding her, but that slows her speech, gives it a brittle edge.

“Even as hapa ~being half Hawai’ian~ my mother taught me about kuleana. Loosely translated it means “responsibility”. It’s dis concept of reciprocal relationships between the person who is responsible, an’ the things or persons they are responsible for. As Hawai’ians, we have a kuleana to our ‘aina, our land. To care for it and to respect it, and in return... the land has the kuleana to feed, shelter and clothe us. Through that relationship we maintain balance within society and with the natural environment. But you look at the world and everything is for sale, raped by greed and the need to consume. To conform. This... this is a sign of what my uncle’s people call the Apocalypse, but not like in disaster movies. Maybe tomorrow, I’ll tell you all about that.

“Another concept is...Pono. There’s no real translation for it, it’s a concept that incorporates many things. But many people use it to imply righteousness, but not like the way it’s used in society today. For us, anyway, it’s a very strong cultural and spiritual concept for a state of harmony and balance. So you can see how they relate? By accepting your kuleana and making sure you act on them in the right way, you are living pono. Living pono means to make a conscious decision to do the right thing in terms of self, others, and the environment. And we make no distinction between human and animal or plant, in that way.” She slants that hazel gaze toward him via one eye slitted open to make sure he’s following along. “And I don’t mean that cutting down a tree is the same as say murder. But in a way, it is. You are killing something that was alive. You are taking its mana. If you do it with proper thanks and reverence, if you ensure that you are doing it sustainably, to feed yourself or build a shelter for your family, then you’re behaving within your kuleana. But clear-cutting an entire rain-forest so you can build a luxury golf-course and resort, displacing thousands and thousands of indigenous wild life and polluting the waters and destroying layers and layers of earth, not to mention the risk of exposing entire tribes of people who have no natural resistance to what are common, immunised illnesses? That is no different than slaughtering those very same lives in a far more expedient way. And I don’t know if you think I’m crazy, or if I am over-simplifying the tragedy that we as an entire world of people are creating and contributing to but you can see...the earth herself is restless. She is angry. And those throes of agony ~the global warming, the spirits crying out, the violence and disease...they are all symptoms of that anger, because people as a whole have lost their way. They trust too much in technology and in coping mechanisms that only breed more trouble...”

She’s momentarily lost in the weeds, but there’s no denying the passion in her voice as it trembles with pure and unbridled rage at society’s ills. And not just the ones that have landed on the Sleepers whom they are, in their own ways, charged with protecting, but the ones amongst their own kind and those of the others. “So I suppose, the dilemma I just cannot begin to understand is...with so much happening, and the world around us vanishing with every breath...why are we unable to reach an understanding. Why do we have to fight this war about whose mana is bigger, is better than someone else’s. And not just the Traditions ourselves. Our infighting is bad but we can typically talk things out. I specifically mean this war with the Technocrats. Their science isn’t doing much to improve lives these days and more and more people are looking for alternatives, for the Old Ways. Why not work with us instead of trying to kill or imprison us? Or why can’t some of us... Verbena and Dreamspeakers... some of you Euthanatos- why can’t we make a pact with the Wolfkin. Or the last of the lizard kings-” She glances askance at him a second time in a very playful and knowing fashion. Which is disturbing considering the nature of the remains in the ice chest she was tossing into the water just moments ago. “It isn’t like some of us hasn’t been busy keeping their kin fed. So I think just like the Traditions coming together, or the Technocrats forming their union, maybe it’s time we put political and spiritual beliefs to the side and just work together for the things we want. We’re all really trying to fight the same enemy, and I promise it isn’t you, and it isn’t me and it isn’t Bil..it isn’t any one person. There is evil out there. Real, terrifying evil. Take this guy. What he did to those kids...He was a disease. And like the healer I am and like...like the man you will some day become, we did what was right, for everyone.” Beth shudders then shakes her head. “I don’t even know how to answer your question, or if I did. All I can say is...there’s no part of me that has any shame for the way I live my life, and therefore there’s no moral dilemma. But if one comes up, I promise you’ll be the first line of defense for my understanding and sanity.”

#mynameisanakin#Like A Sad Hallucination|Anakin Skywalker#Like a Memory in Motion|Anibeth#The Trunk You Kept Your Life In|Mage the Ascension#Crescent City Blues|Nola#Reborn on the Bayou|Louisiana

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

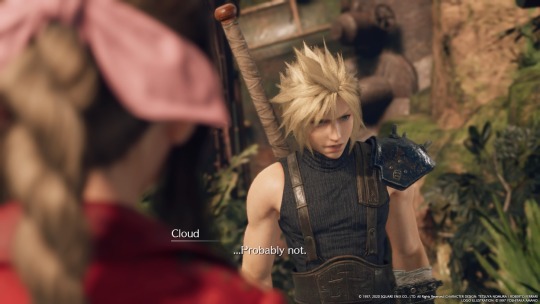

The Rebuild of Final Fantasy VII: Your Expectations Will (Not) Be Met

I apologize for the stupid title and I promise I’m going to talk about the Final Fantasy VII Remake, but I have to get this out of the way first. Sometime in the mid 2000s, acclaimed artist and director Hideaki Anno announced that he was going to remake his beloved anime series Neon Genesis Evangelion the way it should have been the first time, free from technical and budgetary restraints. Evangelion had a notoriously strange ending when the original anime aired, consisting of character talking over still images, abstract art, and simple animations. It was highly polarizing and controversial. Anno, for his part, received death threats and the headquarters of the studio that produced the anime was vandalized. Soon after the initial uproar Anno would direct The End of Evangelion, a retelling of the final two episodes of the anime, and that seemed to mostly satisfy the fanbase. Looking back now, The End of Evangelion wasn’t “fixing” something that was “broken,” no, it was a premonition: a vision of things to come. Why remake the ending when you can just remake the whole damn thing?

The mid 2000s also saw the birth of the Compilation of Final Fantasy VII: a sub-series of projects expanding the universe and world of the video game that had “quite possibly the greatest game ever made” proudly printed on the back of its CD case. The Compilation consisted of three games, all on different platforms, and a film. First was Advent Children, a sequel to Final Fantasy VII, where three dudes that look like discarded Sephiroth concept art all have anime fights with our beloved protagonists, culminating in a ridiculous gravity defying sword fight between Cloud and Sephiroth. Before Crisis and Crisis Core are prequels that expand the story of the Turks and Zack Fair, respectively. Then there’s Dirge of Cerberus, an action shooter staring secret party member and former Turk Vincent. Were these projects good? I’d say they were largely forgettable. Crisis Core stood out as the obvious best of the bunch and I think may be worth revisiting.

As a business model, the practice pioneered by the Compilation would continue on and eventually brings us FFXIII (and sequels), FF Versus XIII (which would later become FFXV), and FF Agito XIII (which would later become FF Type-0). If that’s all incredibly confusing to you, I’m sorry, I promise I will begin talking about the Final Fantasy VII Remake soon. Suffice it to say, both Final Fantasy VII and Neon Genesis Evangelion have a certain gravity. They punch above their weight. They are both regarded as absolute classics, flaws and all. And yet, in both cases, the people responsible for their creation decided that their first at bat wasn’t good enough and it was time to recreate them as they were meant to be all along. I think this way of thinking about art is flawed, limitations are as much a part of the creative process as vision and intent. Yet, we find ourselves in a world with a remake of Final Fantasy VII, so I guess we should talk about it.

From this point forward, there’s going to be major spoilers for every Final Fantasy VII related media. So, be warned.

So, is the Final Fantasy VII Remake any good? To me, that’s the least interesting question, but we can get into it. FFVIIR is audacious, that’s for sure. Where Anno condenses and remixes a 26 episode anime series into four feature length films, the FFVIIR team expands an around 5 hour prologue chapter into a 30+ hour entire game. Naturally, there will be some growing pains. The worst example of this is the sewers. The game forces you to slog through an awful sewer level twice, fighting the same boss each time. This expanded sewer level is based on a part of the original game that was only two screens and was never revisited.

Besides the walk from point A to point B, watch a cutscene, fight a boss, repeat that you’d expect from a JRPG, there’s also three chapters where the player can explore and do sidequests. The sidequests are mostly filler, but a select few do accomplish the goal of fleshing out some of the minor characters. You spend way more time with the Avalanche crew, for example. Out of them, only Jesse has something approaching a complete personality or character arc that matters. The main playable cast is practically unchanged which was a bit surprising to me. I figured Square-Enix would tone down Barret’s characterization as Mr. T with a gun for an arm, but they decided, maybe correctly, that Barret is an immutable part of the Final Fantasy VII experience. Also, it’s practically unforgivable that Red XIII was not playable in the remake considering how much time you spend with him. I don’t understand that decision in the slightest.

The game’s general systems and mechanics, materia, combat, weapon upgrades, etc. are all engaging and fun and not much else really needs to be said about it. I found it to be great blend of action/strategy. Materia really was the peak of JPRG creativity in the original FFVII and its recreation here is just as good. The novelty of seeing weird monsters like the Hell House and the “Swordipede” (called the Corvette in the original) make appearances as full on boss fights with mechanics is just weaponized nostalgia. In general, the remake has far more hits than misses, but those misses, like the sewers and some of the tedious sidequests, are big misses. It is a flawed game, but a good one. If I were to pick a favorite part of the game, I’d have to pick updated Train Graveyard section which takes lore from the original game and creates a mini-storyline out of it.

If that was all, however, then honestly writing about Final Fantasy VII Remake wouldn’t be worth my time or yours. The game’s ambition goes way further than just reimagining Midgar as a living, real city. There’s a joke in the JRPG community about the genre that goes something like this: at the start of the game, you kill rats in the sewer and by the end you’re killing God. Well, when all is said and done, the Final Fantasy VII Remake essentially does just that. Narratively, the entire final act of the game is a gigantic mess, but if you know anything about me then you know I’d much rather a work of fiction blast off into orbit and get a little wild than be safe and boring.

In the original games, the Lifestream is a physical substance that contains spirits and memories of every living being. Hence, when a person dies, they “return to the planet”. It flows beneath the surface of the planet like blood flows in a living person’s veins and can gather to heal “wounds” in the planet. In the original game, the antagonist, Sephiroth, seeks to deeply wound the planet with Meteor and then collect all the “spirit energy” the planet musters to heal the wound. The remake builds on this concept by introducing shadowy, hooded beings called Whispers. The Whispers are a physical manifestation of the concept of destiny and they can be found when someone seeks to change their fate, correcting course to the pre-destined outcome. Whispers appear at multiple points throughout the game’s storyline both impeding and aiding the party. The ending focuses heavily on them and the idea that fate and destiny can be changed. We receive visions throughout the game which some will recognize as major story beats and images from the original game. After dealing with Shinra and rescuing Aerith, the game immediately switches over to this battle against destiny and fate that you’re either going to love or hate. The transition is abrupt and jarring. While Cloud has shown flashes of supernatural physical abilities throughout the game, suddenly he has gone full Advent Children mode and is flying around cleaving 15 ton sections of steel in half with his sword. The party previously took on giant mutated monsters, elite soldiers, and horrific science experiments, but now the gloves are off and they’re squaring up against an impossibly huge manifestation of the Planet’s will. Keep in mind, in the narrative of the original FFVII, the Midgar section was rougly 10%, if that, of the game’s full storyline. This is, frankly, insane, but I’d be lying if I didn’t love it.

The Final Fantasy VII Remake, with its goofy JRPG concluding chapter, is forcing the player to participate in the original game’s un-making. We see premonitions of an orb of materia falling to the ground, we see an older Red XIII gallop across the plains, we see a SOLDIER with black hair and Cloud’s Buster Sword make his final stand, we see Cloud waist deep in water holding something or someone. We all know what these images represent, they’ve been part of imaginations for decades. But the Final Fantasy VII Remake allows us (or forces us, depending on perspective, I guess) to kill fate, kill God, and set aside all we thought we knew about how the game would play out post-Midgar. The most obvious effect of our actions is the reveal that Zack survived his final stand against Shinra and instead of leaving Cloud his sword and legacy, helped him get to Midgar safely. I have my doubts and my worries about the future of this series. I’m not sure when the next part of the game will be released or what form it will come in, but I can’t believe I’m as excited as I am to see it.

Of course, part of me wishes they’d just left well enough alone. Remakes are generally complete wastes of time and effort. Not all, but most. Maybe I’m, to borrow a term from pro wrestling lingo, a complete mark here and I just love JRPGs and Final Fantasy VII so much that I’ll countenance close to anything bearing its name. I’ve tried my best to be as critical and fair as possible to the game and I hope that if you’re on the fence and reading this I’ve maybe helped you decide if it’s for you or not. I think the Final Fantasy VII Remake is worth your time if you’re looking for a good, meaty JRPG. It’s not perfect and it’s final act is insane, but that just makes me love it more.

Have you ever wondered what it would be like for Zack, Cloud, and Aerith to face Sephiroth in the Planet’s core? I know 15 year old me did. And he may get his wish.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

So this post I just reblogged got me thinking about the difference between definitions and descriptors, but that wasn’t really on topic, so off to my own post, I guess. This got... very long, and is really just me rambling about how I like to discuss the language I use to describe my relationships.

I tend to refer to this with language like “top-down” and “bottom-up” processing, but that’s just me lifting concepts from a psych class because they made sense to me. I’ve also described it as “external” or “internal” ways of defining things, but at least in the context of my relationships, I’ve been more and more often referring to it as the difference between a definition of or a descriptor for my relationships.

In practice, because I like words that people have already coined and used in these discussions, I tend to use a lot of language that already comes with a definition. And, to further complicate matters, except when trying to examine the theory behind my relationships, I don’t really .... differentiate my use of those words from being definitions of my relationships.

So before I settled on framing it as “defining/describing,” I thought of it as the difference between a top-down or a bottom-up understanding of my relationships. In both, the relationships just... is. But how it’s framed, and thus how it’s understood, changes from how you approach it.

So, in the grand tradition of using myself as an example, this is what my relationships “is”:

I am engaged to a woman, S

I am dating a man, N

We ultimately plan on the three of us living and raising our children together

We don’t have any rules about not dating other people

None of us have sought out or started any relationships outside what we already have

S has her own partners; they don’t live with us and are not planning to

In a top-down approach, I start out with labels with set definitions. Words like “vee” or “polyamorous” or “non-monogamous” and “open” or “closed.” And then I apply them to my relationships, and if they fit, if they seem to describe what’s happening there, I use it. In another way of putting it, I define my relationship with these words. Pros: consistent language. Cons: the age old dilemma when no existing language seems to encapsulate what you’re doing or experiencing.

In the bottom-up approach, I start with my relationship. And I take words (with relevant pre-existing definitions) and I define them based on my relationship. Pros: feels authentic, feels organic. Cons: what do words mean???

I really don’t like this binary! I didn’t like the failure mode in top-down - words and their definitions were a grab bag of things that seemed to fit no problem (vee) and things that looked like they should fit, but felt like trying to stuff myself into a too-small shoe (non-monogamous). But the bottom-up failure mode honestly felt worse, because, great, I’ve got all these words to define my experiences, but either people are already using them, but defining them slightly differently (polyamory), or people have never heard of them, and in any event, it made having meaningful discussion nigh impossible.

Okay, and now to jump tracks (I swear it comes together): When I first started out reading about polyamory, it seemed like again and again the “polyamory failure mode” I came across was Rules. Rules are bad, advice blogs and experienced polyamorists told me. Rules do not protect you - they can even make you more vulnerable. Instead, they said, you should have Boundaries.

I’ll be honest, the distinction made like, absolutely zero sense to me at first. Rules and Boundaries were like... literally the same thing? You could have a Rule around “no unprotected sex with outsiders” or a Boundary around “I don’t have unprotected sex with outsiders or partner’s who have unprotected sex with outsiders.” But they both described how you felt about X, here, unprotected sex, so....?

But it’s all in the framing, isn’t it? A Rule frames your feelings about unprotected sex as something your partner is required to do (or not do); a Boundary frames your feelings as how you’ll handle that situation. And once I thought about it like that, Boundaries do seem healthier because ... relationships based on forcing compliance from your partner don’t work. Like, really, all you get is resentment, on both sides.

Another way to look at it is that rules are dogmatic, while boundaries are flexible. Rules are based in How It Should Be - and their failure mode is what happens when things don’t fit in that neat little box. Boundaries are, well, I think it’s more than a bit generous to define them as How Things Are, but they certainly flex and mold to the relationship, rather than demanding the relationship conform to them. (I’ll be honest tho, I don’t really have a “failure mode” for boundaries, because imo every failure mode I’ve seen is people treating boundaries as The Correct Way To Phrase A Rule. anyway.)

So, to tie this back together, while thinking about these, it suddenly seemed obvious that the failure modes of a top-down relationship frame and Rules were basically the same. Conceptually, they were both about defining something in the relationship but the relationship not conforming to that definition, right?

Well, whew, that means bottom-up frameworks are the Boundaries here! ... Except that still totally failed to address the failure mode I felt existed in bottom-up framing.

And then I was like... but... the failure mode of Boundaries is making Rules but calling them Boundaries. Or, another step removed, treating boundaries as the absolute inverse of rules. Was I treating bottom-up framing as an absolute inverse of top-down?

Well, yeah. And tbh that’s why I don’t really use this language much anymore, because .... it’s still the definition that makes Total Sense. Basically, if top-down is “words define relationships” than bottom-up was “relationships define words.”

And that was when I started thinking about “defining” relationships. Why do we define them? Who benefits? What happens if we don’t?

In my galaxy-brained fever, “defining” seemed analogous to “rulesing.” When I “defined” a relationship using pre-existing words, I was making demands on that relationship (ie placing a rule). And when a relationship behaved outside of it’s pre-set definition, it broke that “rule.” Suddenly, anarchy.

Defining the word by the relationship still sucked tho. But if “defining was rulesing,” then maybe words and relationships were supposed to interact without either defining the other at all.

Which looped me back all the way to the beginning. “The relationship just ... is.”

Tbh I’m not sure exactly how I made this next leap, and I suspect the fact the describing starts with “de” and I think “defining/describing” make an aesthetically pleasing foil to each other was a big one. However I made it, I was now thinking about “what if [word] described a relationship, but wasn’t how the relationship was defined?”

So, like, uh, what’s that even supposed to mean?

Okay, so, back to my relationships. I have at various points, sometimes simultaneously, described both as “open” and “closed.” Why?

Well, technically, they’re both open - we are each free to go out and seek additional partners in whatever capacity makes us happy. And that’s a useful word, to be able to sum up the idea of “exclusivity is not a requirement of my relationship.” But (and maybe this is just, we don’t hang out in the right poly circles) “open” always seemed to come with a second definition: “we are interested in having other partners.” And that is definitely not us, at least right now.

I’ve seen closed used two ways, in parallel with open, as well. Sometimes it gets used to mean that a relationship is exclusive (most commonly I’ve seen this in reference to monogamous relationships, especially when talking about when a couple “opens up” their relationship); other times, it’s defined as “we are disinterested in having other partners.” So we tend to use closed a lot, too, because it’s an easy way of signalling that we aren’t interested in other relationships, even if exclusive isn’t really accurate. I honestly prefer closed, because we’re all pretty actively disinterested in other relationships.

Anyway, the of/for distinction matters to me too. “The definition of my relationship” is supposed to sound and feel immutable - or breakable, if something changes. “A description for my relationship” is meant to be rooted in how my relationships are experienced, and focused on using the available language to explain to other people the inner workings of it, so that we can all have productive conversations about polyamory.

I really do feel that, when I focus on using words as tools to describe the experience rather than facts about “what my relationship is”, I get to spend more time focusing on what my relationship is. I can be flexible in what words I use and when, because sometimes what matters is the context that my relationship is existing in. And personally I think it gives me greater freedom to frame something as how I see myself respective to my relationship, versus how I see my relationship.

#j rambles#polyamory#was there a major point to this?#i dont really think so#i like dissecting the theory behind my relationships#its a perennial fave hobby#long post#orz im sorry this got so long#may#14#2019#20190514

1 note

·

View note

Text

Best Dating Apps For Nerds

Attention smart home nerds, POF is one of the first dating apps that you can access from Google Home with Google assistant. Another major plus: POF will help you develop your profile and suggest what to write based on your relationship goals (s ay, casual versus looking for something more serious.), so you can get better matches right out of. The List of Best Geek Dating Sites. This geek dating sites reviews is specifically designed for people who are more of finding dating sites online. The list of top geek dating sites will help you find the geek dating sites that suit your preferences. The site’s extensive search filters give it a high ranking in the top geek dating.

Best Dating Apps For Nerds 2020

Best Dating Apps For Nerds 2018

When looked upon with the rose-colored glasses of nostalgia, the dating we did in our 20s was the stuff of romantic comedies, especially when compared with what it’s like a decade later. While it’s actually easier to date in your 30s in the sense that you know yourself better, by the time you reach a certain age you’re just, well, SATC’s Charlotte said it best: “I’ve been dating since I was 15. I’m exhausted. Where is he?” Sheer exhaustion is the reason going to bars is a no-go most nights—especially given the inevitable epic hangovers and a lack of single girlfriends with whom to wing-woman—but luckily, this is the digital age, so we can meet lots of men without ever leaving our Netflix accounts unattended. Here, 12 apps to try if you find yourself single—and ready to mingle—in your 30s (plus, how to take a perfect selfie for your profile).

Homepage Image: Adam Katz Sinding

Coffee Meets Bagel

In a recent study, analytics company Applause ranked apps based on their user reviews, and this one came in third, which is promising. While the app once sent daters only one match per day, which was helpful for those who feel the 'shopping' element is a little icky, it recently switched things up so that men receive 21 matches per day whereas women receive just five. Before you delete it based on this inequity, know that the well-intentioned people at Coffee Meets Bagel made these changes based on user feedback—apparently, men like quantity and women like quality. Shocking!

If you don't want to lose the serendipitous aspect of real-life dating, you should probably sign up for Happn. This app promises to match you to people with whom you've crossed paths in the non-virtual world, somehow making things feel a little more organic. If you, like us, live in a sprawling city like Los Angeles, you know how important convenient geography can be in terms of making a relationship last.

Sparkology requires that men be graduates of top-tier universities in order to join, which feels a bit gross considering it doesn't have the same standards for women. Men are also subjected to a points system, which is purported to help ladies know which ones are serious (a feature we can definitely get behind). In order to join, technically you must be invited by a current member or the Sparkology team, but if you click on the 'Join' button, you're asked to link your Facebook profile for evaluation.

We don't think anyone should be ashamed to be 'caught' online dating; however, some of us may not so much appreciate our colleagues or future colleagues knowing what's up in our romantic lives, so the fact that The League hides your profile from LinkedIn and Facebook contacts is a big plus in our book. Another thing we like about The League? The platform kicks people off if they're not actively dating: No looky-loos allowed. The League has recently shifted its strategy somewhat to become events-focused, as it's hoping to transition into something akin to a members-only club like The Soho House rather than just a dating app. The League is only available in San Francisco, New York and Los Angeles, and its waiting list is allegedly 100,000 people long. Good luck!

Most of the women we know who frequent dating apps at present are on Bumble and report good experiences—it ranked fourth on that aforementioned list based on user reviews. This app is known for tasking women with the first move (once a match has been made)—which is great if you'd like to reduce the number of obscene things total strangers feel justified in using as pickup lines on some apps. On another note, Bumble's just announced the launch of BumbleBizz this fall, which is basically swipe-based networking. We're intrigued.

If you're one of the 'old people' who has gotten on board with Snapchat in a big way, you might want to try Lively, the newest app on the market. We have a feeling its demo will skew 20s, so if you're looking for a slightly younger man, this could be the perfect platform for you. Your Lively profile will pull videos and images from various apps on your phone and edit them together to tell a complete story about you. The app comes to us from the creators of dating website Zoosk.

Best Dating Apps For Nerds 2020

If you think your life is a rom-com, or should be, Tindog might be the app for you. It matches your dog with another dog, which is definitely the perfect setup for a meet-cute if ever we've heard one. Something to consider before joining, however, is how hard it is to be rejected in online dating. Now imagine how hard it will be for you when your beloved, perfect pet is rejected, as happened here. We just don't want you to get hurt....

If you're into astrology, Align is pretty fun, and it'll save you the trouble of finding out your signs are incompatible down the line. We don't know how serious the contenders are on this platform—we don't use it as, to be honest, we barely even know our own sign—but if nothing else it will provide a welcome distraction from the tedium of scouring the digital universe to find your cosmic match.

OkCupid has a patented Compatibility Matching System, which uses complicated algorithms to pick your matches. Given that all we've been doing thus far to pick our men is saying, 'He's hot,' we can't help but think this would be an improvement. Though you can choose to select less commitment-focused options in terms of your dating goals, OkCupid tends to feel more adult and therefore more serious in nature than other apps. This can be a good thing if you're looking for someone who will step off the dating carousel with you at long last. It was also ranked number one by Applause in terms of user reviews.

According to Time Magazine, 82% of Match users were over the age of 30 as of 2014. This has likely changed somewhat given that in the same year, Match redid its mobile app to include features more akin to Tinder than OG Match. Still, Match tends to draw a more serious crowd than many other apps, in part because elements of the platform require payment.

Some of us have personal feelings about this one—which we won't share because, diplomacy—but suffice it to say that you will definitely meet a specific type of person on this platform. Raya is exclusive and basically requires that you have a cool job, know cool people and have a lot of those cool people following you on Instagram. If that sounds like your kind of filtration system, we say go for it. Just be warned in advance that it's unlikely that the attractive celebrity with whom you're matched will be dating only you anytime in the near future.

We recently added Canada to our list of countries worth moving to. Maple Match hilariously promises to enable your move north by partnering you with a Canadian. We're pretty sure this app is a joke—you can only join the wait list for now—but we're hoping someone invents it for real, stat.

Best Dating Apps For Nerds 2018

By our 30s, ideally we've broken bad habits and patterns and are now only dating people who would make appropriate partners. If you, however, laughed out loud at that statement (we did), you might want to consider signing up for Wingman. This app leaves the fate of your dating life in the hands of your friends, who are the sole deciders when it comes to who you will or will not go out with. We're guessing the results of such an experiment would be vastly different than anything we've experienced while steering our own ship, and we're so down to find out.

0 notes

Text

Why Am I Here?

I think a lot. Probably too much by some standards, which is one of the reasons I wanted to join the Peace Corps. Once upon a time I believed if I made it to this position I would be forced to think less and do more. However, over the past six months I’ve experienced the opposite. Without mind-numbing mental distractions like Instagram and Facebook readily available while I’m in my rural site, and with the heat-forced downtime that occurs between noon and five p.m., I find myself thinking all the time. Not just in a hazy, half-aware state, but actively considering a handful of topics over and over again trying to find some satisfying conclusion that may or may not exist. So I’m not sure if the amount I think has changed since coming here, but perhaps the way I do has. Maybe now it’s more focused, more linear, less wiggly and sporadic. Maybe it’s more dense and easier to hold in my hand, like pudding versus water. Maybe it hasn’t changed at all and I’m just making it all up.

One topic currently seems to have a more substantial presence in my mind than the others, though. Sometimes it burns like a roaring campfire and I’m completely captivated and sometimes it nags silently like a mango string caught in my teeth that I run my tongue over again and again without actually making an effort to remove. When I sit on the floor of my hut at 6:30 am drinking Nescafe, when I fill my water bucket at the forage in the silent woods, when I escape the afternoon sun by doing crosswords in bed, when I sit with my family in the evening as we wait for dinner to finish cooking, I always come back to the same thought - why the fuck am I here?

For anyone reading this who doesn’t know, Senegal is a small West African country that happens to be the furthest western point on the African continent. I honestly don’t know that much about Senegalese history because all the empire formations and and dissolvements make my head spin, but I do know that it is certainly a very rich and diverse history, which has led to a very rich and diverse culture today. Although French is the national language, apparently 36 different languages are spoken in Senegal today, and each language corresponds to a different ethnic group with it’s own stories and traditions and beliefs. In my own region of Kedougou, I can travel between Bassari, Pular, and Jaxanke villages in just a few hours, and then if I travel up to any of the northern regions I find myself surrounded by Wolof or Pulaar du Nord or Serer.

So, take a trip in a time machine back to maybe the 7th century and you’ll find all these groups of people living their lives, forming empires and kingdoms, disbanding, migrating, adopting Islam, you know, whatever, the usual, until the advent of globalization at the end of the 15th century. At that point, Europeans began competing for trade and conquest in Senegal (like they did in almost all other non-white countries, as y’all know. I have a few other colorful ways to describe this but since I have family reading and I already dropped a fuck once (twice now, sorry) I’ll keep it tame.)* until 1677 when France won by gaining control of Goree Island, which is known for being a purchasing base in the Atlantic Slave Trade.

Travel forward in the time machine to 1961 and Senegal becomes independent from France. After centuries upon centuries of existing as a region under various kingdoms, then 300 years under French rule, Senegal becomes a country with a border, a tax system, a school system, elected officials, all that stuff. Now travel forward in the time machine to today, 2018, 57 years later.

SO MUCH BACKDROP. Was all that even necessary for what I’m about to talk about? We’ll see, I guess.

Living here, I see a lot of European and North American presence. Asian presence too, actually - a lot of the roads being built are Chinese construction projects, and the Renaissance Monument in Dakar was given as a gift from North Korea. There are other development organizations like UNESCO and World Vision, some religious missionaries, some adventurous tourists traveling on their own, some old French women sunbathing on the beaches of Mbour, and of course the obnoxious buses crammed full of European tourists coming to see a waterfall and stop by the surrounding towns to take photos of ~village life~ as if strolling through a zoo.

As a white person here I’m perceived differently based on which of these groups of white people Senegalese people have interacted with more. When I travel anywhere outside my village I hear the children sing-song chant “toubako okkan cadeau!” which means “westerner, share a gift with me!”. Sometimes the adults engage me too when I go to a boutique or wait for a car at the garage. They like to ask me if I’ll take their baby with me back to America, if I’ll give them my earbuds, my cell phone, or my dress, or if I’ll marry their old crusty-ass uncle I don’t even know. When I travel up to Thies I don’t get chanted at quite as much and am almost ignored, which is nice. The few times I’ve been to Mbour I’m almost ignored except for the occasional beach-walking knick-knack seller begging me to be their first customer of the day.

Even though they are just children, I get so incredibly annoyed sometimes by the chanting. I usually ignore it and go about my day but sometimes I just want to scream “my name is not Toubako, it’s Binta, and I don’t have a fucking gift, leave me alone and let me walk or bike or buy a piece of bread or whatever the fucking I’m doing at the moment.” The adults can be just as irksome, too. I don’t usually get into it and play these comments off as jokes but they make me so uncomfortable. I want to tell them “stop asking me for things. Every time you see me you only ask me for things. I came here to teach, to work, to plant at least like one fucking tree, not to take your baby or marry your god-damn uncle.”

I think I’m up to four fucks now, sorry. God, that’s five.

But I don’t respond because in some ways I feel like I deserve it. Even though I wasn’t here between 1677 and 1961 selling humans from Goree Island, even though I’m not one of these oggling, bus-going, camera-toting tourists, because I’m white I’m still part of that story. And in some ways isn’t “international development” another form of colonialism, of imperialism? Western groups coming in with resources and knowledge trying to fix what they perceive as problems? If the people of Senegal continuously rely on foreign aid organizations to supply resources and technical expertise, how sustainable is that for development in the long run?

So this is where my thoughts lead me every day. What’s my role as a volunteer here? How can I act as a white person without perpetuating colonialism? How can I work and learn here while being the least imposing as possible? In Peace Corps we’re told the role of a volunteer is to be a mentor, a teacher, a co-facilitator, a co-planner, etc. There’s a huge focus on “people-centered” work. Don’t do anything your village doesn’t want. Don’t force your own projects because when you leave no one will continue it. I think I feel comfortable with this part. So far I’ve really been trying to feel out my village for what they want, what they need, and what they’re willing to work toward. If no one wants to make a compost pile or build a tree nursery, I’m not going to force it. I try to see myself as a supplier of information, not an iron-fisted environmental ruler.

But even if I am trying to work with my village, even if I am truly trying to be this mentor/teacher/facilitator figure, and not a tyrant or giver of gifts like some other development organizations can be, why is that my responsibility as an American? All my technical training in Thies was done by Senegalese people. Wouldn’t this whole program be way more effective if Senegalese people trained other Senegalese people? People who live here and truly understand their land and their culture? People who don’t have to spend a year just trying to learn a language and fit in? People who aren’t going to go home to America or Canada or Japan after 2 years?

Well then I think maybe it’s not just about the work. The work is so fun, it’s a blast, it’s been my favorite part in village. Helping someone build a tree nursery, doing a small training, getting my hands dirty planting seeds or amending a garden bed - it’s fantastic and I say that without a single drop of sarcasm. But there’s three goals in Peace Corps - the first is about the work, the second is about sharing American culture with the host country, and the third is sharing host country culture with Americans. And I think many volunteers have a fourth, personal goal of learning about themselves or some kind of self improvement. That’s my other favorite part so far. The opportunity to challenge myself, to learn, to think in a focused way and not just bounce all over the place. But did I have to come all the way to Senegal to do that? Are there experiences I could have had in America that would have been this formative? If I’m here just to learn, is that another form of exploitation? Am I just using my village’s daily life and culture as a means to only better myself? Maybe I should really focus my efforts on this whole cultural exchange part?

I don’t know! I don’t know anything!

I’m not sure what my goal is in writing this post, but there was something inside me nagging me to put it down in type and send it into cyberspace. I do really appreciate my service in Senegal so far. I don’t want to leave, I don’t want to go home. But I think this topic is something I will continue to come back to again and again over the next year and a half. Maybe other volunteers will see this and relate or offer some insight? Maybe some history nerds will call me out on all the mistakes I made in the earlier paragraphs? Maybe people will tell me to shut up and get back to the cool tree stuff or post more pictures of my dog?

Like I said, I don’t know.

If you got this far, thanks for reading. That’s all for now.

-Maggie

*Way earlier in this post I put a little asterisk, if you remember. I have a book recommendation. If you’re interested in globalization, colonialism, and/or potatoes I highly recommend 1493 by Charles C Mann. It’s the story about how the face of the Earth completely changed with the first Europeans coming over to North America. It tells a very, very interesting story and I encourage anyone interested in learning even a little bit to read it.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ugh I’m Soooo Out of Energy!

Hey everyone! This weeks topic is a little bit different than those in the past because it’s a resource in a different way than we have been focusing on. Today we’re going to be talking about energy: Renewable vs Nonrenewable and the advantages and disadvantages of both. Let’s dive in! First, what is energy? Energy by definition is the ability to do work. In order to move any part of my body, or even just to think, my brain has to perform work in order to do the desired function. Energy can come in many different forms like kinetic (moving my arm), electrical, chemical, potential, mechanical, and more. Energy is all around us and fuels every exchange we make in the world while we’re living here. Fossil fuels like coal, natural gas, and oil are examples of nonrenewable energy sources. When the energy stored in a fossil fuel gets used up, there’s no getting it back. They take millions of years to form within the crust of the Earth under very specific conditions, so they technically are renewed at some point, but they’re not renewable in a human’s life time. Other sources of energy like wind, sun, and flowing water can be used to create energy over and over again, which makes them a renewable energy source. Recently, the world has been trying to switch over from a predominantly non-renewable energy market to one that is more sustainable and utilizes more renewable energy sources.

The reason many people still use fossil fuels (especially developing countries) as energy sources is because they are cheaper to use than renewable sources. However, fossil fuels are detrimental to the overall health of the planet. Fossil fuels are the leading cause of Carbon Dioxide in the atmosphere, which is also the leading cause of global warming and climate change (EPA).

However, as science and technology progress we as a society are coming closer to unlocking the secret to renewable energy. In current years, the cost of renewable energy has been decreasing and thus the use of renewable energy like solar power has been increasing in popularity. In the US about 18% of all energy used came from renewable sources in 2017 (Wales, 2018). Countries like the US and Canada have also made pledges to produce almost entirely renewable energy by the year 2050, with cities like Los Angeles pledging to be 100% renewable by 2050 (Walton, 2019). Clearly, people want to use renewable energy because they know it is better for the planet and the well being of everyone living on it. The problem is that companies still prefer to use fossil fuels so that they can make a bigger profit, because most people in this world thrive off of a capitalist economy in the United States, whether they know it or not. That goes into another rant thought, so why don’t we get back on track and talk more about energy, shall we?

As mentioned in my blog before, energy comes with different qualities depending on how it is used and sourced. For instance, high quality energy comes from high-quality sources, and it takes high-quality energy to mine more high-quality energy. We also know that when high-quality energy is used, some of it is lost as low-quality energy that can’t be used nearly as effectively. Net energy is the amount of usable high-quality energy that is given off from a certain quantity of an energy source. When oil was first being used as a source of energy, it had a higher net energy because most resources were found in large concentrated deposits that weren’t too deep underground, so it didn’t take that much energy to drill down for it, transport it up to the surface, or transport it to useful energy to consumers. Now however, as the hunt for oil slows down due to supplies dwindling at alarming rates, the oil is less concentrated and loses more to low-quality energy, the net energy decreases. Not only does it require more energy to find oil nowadays, but it is also much more expensive. This loss of high-quality energy to low-quality energy is known as energy waste. Almost 84% of energy used in America is wasted, that means only 16% of what Americans pay for for electricity and energy is actually used. That’s a huge waste of energy! One of the biggest wastes of energy comes from our cars. American society revolves heavily around transportation and unfortunately most people don’t utilize public transportation. Instead, most Americans travel places by using their own car that is typically not very gas efficient. Instead of people sitting together in one vehicle like a bus, most citizens that can afford it choose to drive their own vehicle for the sake of comfort and luxury. Obviously, we all want to be comfortable and having your own car makes that super easy, but it also has a direct attack on our planet. In 2017, only 1.15% of cars sold in the U.S. were electric cars, meaning that the emissions coming from cars were most carbon dioxide, and further lead to global warming and climate change (Bellan, 2018).

The trend for electric cars has continued to rise every year since they’ve been on the market, but the majority of Americans (and people around the world) are using gas-guzzling cars and polluting the planet at a speed unprecedented to anything like it before. Scientists believe that “humanity has about 12 years to avoid the most dire consequences of climate change. To avert catastrophic sea level rise, food shortages, and widespread drought and wildfire, emissions must be reduced by 45 percent from 2010 levels, and by 100 percent by 2050” (Bellan, 2018). That’s a little bit more than a decade! People should be freaking out but most citizens are complicit in watching the earth crumble around them, and I think it’s mostly because of ignorance and a sense of not being important enough to make change. At this point, I don’t think people can say that they aren’t aware of the environmental crises our planet is facing every day. We are constantly bombarded about how awful our planet is doing and how fast we need to act in order to fix it, but most people aren’t doing anything to help. Yeah, people use reusable straws now I guess but that just is not enough. Change has to happen soon, but it needs to be big enough to make a difference as well. I think ignorance comes in to the conversation not in the fact that people do not know what the problem is, but rather that they do not know how to help. I understand why people feel like one person is not enough to make a change, but the reality of this situation is that any help matters. Creating your own compost bin is one more person composting in the world, which means there’s one more person creating healthy soil. And who knows, you might inspire your friend to start composting, and then maybe even your whole neighborhood. Change starts at the small scale and while it may not seem like enough, it leads to bigger reactions. I agree change on a small scale is not enough given the planets current circumstances, but any change at all is a start, and we need some small changes in order to spark a massive movement. In terms of energy, this means that more people need to start buying electric cars or taking public transportation, and supporting companies that provide clean, renewable energy. Without baby steps at the beginning, the solution to the energy crisis can’t start running, and we as a planet need the solution to start sprinting forward if we are ever going to have a chance to reverse the damage already done, and then continue to live sustainably.

Word Count: 1,310 Blog Question: How else can people make the switch to clean energy without switching to electric cars or solar energy? How can we hold corporations more responsible for the type of energy they are using and selling?

Works Cited

Bellan, R. (2018, October 16). The State of Electric Vehicle Adoption in the U.S. Retrieved from https://www.citylab.com/transportation/2018/10/where-americas-charge-towards-electric-vehicles-stands-today/572857/

Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions Data. (2017, April 13). Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/global-greenhouse-gas-emissions-data

Wales, M. (2018, November 01). The Cost of Renewable Energy Versus Fossil Fuels. Retrieved from https://www.naturespath.com/en-ca/blog/cost-renewable-energy-versus-fossil-fuels/

Walton, R. (2019, May 08). LA now biggest U.S. city to announce 100 percent renewable energy goals. Retrieved from https://www.power-eng.com/articles/2019/05/la-now-biggest-u-s-city-to-announce-100-percent-renewable-energy-goals.html

0 notes

Text

Transcript of Bringing Marketing and Product Development Together

Transcript of Bringing Marketing and Product Development Together written by John Jantsch read more at Duct Tape Marketing

Back to Podcast

Transcript

John Jantsch: This episode of The Duct Tape Marketing Podcast is brought to you by Klaviyo. Klaviyo is a platform that helps growth-focused eCommerce brands drive more sales with super-targeted, highly relevant email, Facebook and Instagram marketing.

John Jantsch: Hello, and welcome to another episode of The Duct Tape Marketing podcast. This is John Jantsch. My guest today is Jill Soley. She is a Silicon Valley based strategic product and marketing executive, happens to be the Chief Product Officer at a project management tool called Obo. And, today we’re going to talk about a book that she’s a co-author on called Beyond Product: How Exceptional Founders Embrace Marketing to Create and Capture Value for Their Business. So Jill, thanks for joining me.

Jill Soley: Thank you for having me. Glad to be here.

John Jantsch: So as as we were deciding on the topic for today’s show, you suggested marketing for non marketers. And, I guess it just makes me as a marketer want to know what’s the difference between non-marketing marketers, or marketing for non marketers and just, I don’t know, marketing?

Jill Soley: Specifically, I’m interested and I wrote a book about marketing. And, its audience is really startup founders, small business leaders, anyone launching new products and new businesses, who doesn’t come from a deep marketing background. And, that’s why I suggested the topic, that what I’ve seen is that most founders don’t come from a marketing background, and it’s, I think, obviously super important to the success of their business to understand.

Jill Soley: So, the idea behind the book is that, particularly here in Silicon Valley, there are lots of technical founders, who they have an idea for a company, they start a company, and they have deep expertise in the domain. They have deep expertise in the technology. They’re focused on building product. Maybe they’re sales people. But, most of them aren’t marketing people.

Jill Soley: And, what happens as a result is there’s … Well, there are a bunch of different sort of scenarios. But, many of them, and most of them, lead to companies that aren’t that successful, because there’s often this belief that if you build it, they will come, right? I’ve got the best product, so of course it’s going to be successful. Or they make mistakes that perhaps wouldn’t happen, and they have to do with hiring or mismatched expectations, et cetera, that lead to major points of failure.

John Jantsch: Do you statistics on startups? I mean, I know a lot of people talk about … When I started working primarily with small business, it was like 50% of all small businesses failed in the first three years. I don’t know if that’s statistics accurate or not. But, particularly when it comes to kind of the work you’ve seen with product startup folks, is there kind of a number that people use that … You talked about it not being as successful. But, I mean, is there a number for down outright failure?

Jill Soley: I’ve seen a few different studies that basically sort of are all kind of centered somewhere around this 80% number. I’ve seen some that go as high as saying 95% of startups fail, and some that are a little lower, closer to 70%. But, the upshot is more than half of … It’s not just startups. But, it’s new products in general. So that’s new products in large businesses fail.

John Jantsch: Yeah. Let’s talk about products and product marketers. I mean, you talked about in some cases that this was a scientist or an engineer or something that had a good idea, thought the world needed it, brought it to the market. Is that really much different than say the person that learned how to do accounting, that started in an accounting firm? And, do you see differences between kind of that service and that product in terms of really even what the go to market is?

Jill Soley: Well, differences in terms of the challenges that they face, or difference in terms of the go to market that they need, approaches that they-

John Jantsch: Yeah. I mean, probably the challenges are somewhat similar. But, in terms of the kind of the mentality of how they’re going to go out there and get clients and market the business.

Jill Soley: At the core, I think it’s pretty consistent, right? At the core, the approach is really figure out who your customer is. Figure out what their pain points are. Figure out what their needs are. Speak to those, right? Make sure you’re solving a problem for them. I mean, the fundamentals of marketing are actually pretty consistent. It’s depending on who that customer is, the approach is going to be wildly different. Are you selling to teenagers who live on their phones? Are you selling to moms or elderly people or you name it? These other demographics who may spend time, business people who are at conferences or whatever, right? Where and how you market may be different as a result, but the fundamentals are very much the same.

John Jantsch: Would you say also, I guess, another dynamic that’s at play here when we’re talking about product companies is that a lot of times … I’ll go back to my example of the accounting firm. I mean, there’s already a market established for I got to get my taxes done. I have to have X, Y, Z done. Maybe now I’m just looking for somebody to fill that need for me. Whereas occasionally, or maybe the majority of the time, somebody who’s creating a product that maybe fills a need for something that didn’t exist before, that they actually have to maybe even educate people as to what problem this solves. I mean, would you say that that’s sort of an inherent challenge with a product company?

Jill Soley: I would say those are … But, both of those companies have big, major challenges. But, they’re very different challenges. And, I’ve done both, right? I ran marketing for a company that sold customer support software, right? Very crowded market. And, the challenge is how do you rise above the fray? How do you show that you’re different and get people to pay attention to you versus I’ve done category creation where nobody is looking specifically for that product that you’re selling, and you have to educate them on what it is, and why they needed, and how you could help them and support them. But, I mean, both are inherently hard. They’re just hard in different ways.

John Jantsch: Because you have the word beyond product in the topic, I’m guessing that a big piece of your work and your education is to teach people that it’s not enough to just have a good product. So, how do you have to go beyond that? Or how do you begin to move beyond the fact that maybe you do have a good idea or a good product, I should say?

Jill Soley: Yeah. And, that’s really one of the common problems that I saw was that first stage of a startup, right? Is very much founders get very focused in on the product, building out that product and get the blinders on to the other things that they need to do, right? There’s a lot of stuff that you need to do, that you should be doing early on, and you could be getting benefit from sort of the work you’re doing early on, hopefully with discovery and testing with customers and stuff, that isn’t happening because they’re so focused on product. But, what happens is then all of a sudden that they deem that they have a product that’s ready to go to market, and they haven’t done all the other stuff that they need to do. And so, that launch doesn’t do so well, et cetera.

John Jantsch: Yeah. How important do you think it is to actually develop a product with an ideal customer in mind, or maybe even with feedback from an ideal customer to … So, instead of you’re just doing something in a laboratory, you’re actually doing something that somebody validates while you’re doing it.

Jill Soley: Oh! I believe it’s absolutely essential.

John Jantsch: I mean, is that a step that you see quite often gets completely skipped?

Jill Soley: Yes. I am surprised how often it gets skipped actually. Or there’s not sort of true validation. It’s, “Let me test this with friendly people, right? My buddies, et cetera, who are of course going to support me,” or who the product doesn’t have the … The founders aren’t truly focused on a segment, and they’re sort of trying to meet the needs of too large a segment. And so, they can’t really meet anybody’s needs super well, right? Because you only have so much bandwidth, right? There are bunch of challenges in there if you’re not really sort of focused on an ideal customer.

John Jantsch: I want to remind you that this episode is brought to you by Klaviyo. Klaviyo helps you build meaningful customer relationships by listening and understanding cues from your customers. And, this allows you to easily turn that information into valuable marketing messages. There’s powerful segmentation, email auto-responders that are ready to go, great reporting. You want to learn a little bit about the secret to building customer relationships, they’ve got a really fun series called Klaviyo’s Beyond Black Friday. It’s a docu-series, a lot of fun, quick lessons. Just head on over to klaviyo.com/BeyondBF, Beyond Black Friday.

John Jantsch: A lot of, I mean, you see it in the media occasionally. Somebody has an idea, creates a product, it’s a huge hit and they cash out, and exit do. And then obviously, there are people that that build a product, and then they decide they want to grow the category, and maybe they want to add more products, and maybe they want to have impact in a different way. Is there a completely different path to how you would develop those two companies? If I had the goal of, “I want to get in. Cash out on this thing as fast as possible.” As opposed to, “I want to mature this product or this company.” I mean, are are you going to go about building those companies in different ways?

Jill Soley: Potentially. If you’re really trying to get a quick win, and you’re going to cash out, and you aren’t really trying to solve a problem, sort of really solve a problem and be there long term to kind of build it out and support it and so forth, then I guess maybe you cut corners and stuff such that you make it look good and seem good up front, but it doesn’t really scale, et cetera, ongoing. Maybe you can hear my voice the skepticism around that strategy. And, maybe that’s my own personal bias around … I’m pretty mission-driven, right? I mean, this book is mission driven. I’m trying to solve a problem that I’m seeing, right? All this waste products that are failing for the wrong reasons, right? I mean, you don’t make money on a book, right?

Jill Soley: I didn’t write the book to make money. I wrote Beyond Product because I’m trying to actually help people, offer some, some painful lessons learned, right? That I’ve learned, and that other people have learned along the way, to people who I think can benefit from it. So, I think if you’re really trying to go and build something that actually makes an impact, then you go out and really figure out what the problem is, right? What’s a real problem in the market? And then, work towards really solving it, right? Which isn’t going to be an overnight thing probably.

John Jantsch: If somebody came to you, and they really had what seemed like a pretty good idea, they’d done some research, they’d done some discovery, what would be kind of your five things that you need to make sure you do?

Jill Soley: If they’re at the really early stage, certainly, I would look into the kind of research they’d done, and try and just really understand it, and make sure that they had kind of dug in deeply, and they weren’t sort of suffering from confirmation bias, if you will, right? Which is common. The early research is either with people I know or I’m listening for things that confirm my beliefs instead of that refute it.

Jill Soley: And so, once I’ve kind of dug into that, and have some level … Either have a level of confidence or kind of send them back to do some additional research. And then, sort of as they get to that next stage, where they’re trying to sort of really define, “Well, what is that solution now, right?” I’d try and get them to segment among those early customers who they talk to, right? Who are you really solving for? Get a really clear picture. Maybe try and find some of those people who will be early beta testers.

Jill Soley: And then, figure out kind of what are some of the smallest … What’s that smallest thing that they could provide that might solve a problem? And, begin to do quick iterations maybe. I mean, they don’t even have to be product at that point. They could potentially be paper prototypes, et cetera. What can you put in front of people to really kind of test out your ideas in a cheap and quick way to iterate before you spend a lot of money to build out your solution?

John Jantsch: Are there some folks that you think have done this particularly well, maybe they learned while they were doing it, but in the end, they came out and did a really great job with what you think is a great way to go beyond product?

Jill Soley: I think there are certainly lots of startups that do this. I’m trying to … I mean, you can go back to something like a Salesforce even, right? I mean, their initial product wasn’t really much to speak of, right? I mean, at the end of the day, that’s a marketing company. They have done a phenomenal job of marketing. But, what they did early on is they saw a pain point in the market, right? They saw that there were these segment, these parts of companies, right? These departments and all whose needs weren’t being met, and they weren’t going to be met by this big enterprise product that was there, right?

Jill Soley: So, they went in with a smaller cloud-based product that these departments could implement, and they could get benefit from. And then, they built out their product. And then, they expanded, and they built a platform, and so on, and so on, until they became the Salesforce that we know today, right?

John Jantsch: Yeah. Then, they became the big enterprise product.

Jill Soley: Exactly. We argue about whether it’s a great product today or not, and so forth. But, I mean, if you’re looking at sort of a model for this, I thought that’s a pretty good one. There’s certainly lots of startups as well that are doing this today as well as the ones who are perhaps not.

John Jantsch: Yeah. I think HubSpot actually probably copied that model to some degree. I mean, they were voracious marketers as they were building out the product. And, I think a lot of people, a lot of HubSpot fans, I don’t know how familiar you are with them and their product, but early on, it was a pretty clunky product. And now, they’ve really continued to invest and enhance it. But, they were voracious marketers.

Jill Soley: Well, and one of the things … They got the marketing right. And, there are some interesting sort of marketing strategy that they did really well. And, one of the things that they in particular did is, I think, early on, as I understand it, they had some internal debates about who their customer was. And, Brian Halligan has actually written about this online that they eventually kind of had a heart to heart as a company, right? Internally, they sat down and kind of forced that decision. And, as I understand it from people there, right? It was forcing that decision and picking a very specific target market that really helped their business be successful.

John Jantsch: Yeah. I would agree with that. Let’s talk a little bit about Obo. Are you, as a Chief Product Officer at Obo, are you bringing kind of what you’ve learned? And certainly, anytime you write a book, and then you’re in this position, I think there’s going to be some people pointing to you, “Are we practicing what we’re preaching in the real world?”

Jill Soley: Yep. And, that’s exactly what I’m trying to do there. I mean, right now I’m actually … I’ve come in. Product isn’t out in the market yet. But, we’re close. But, I’m coming in, and I’m actually going back, and just validating some of what has been decided, in terms of strategy to, frankly, make sure that I buy into it, and to figure out sort of where we go from here.

Jill Soley: Its mission, and sort of where it started, was this idea of market first product, right? Focusing in on a market need and understanding the market as opposed to product out, right? Product first. And, there are expert market researchers as part of the team and so forth, right? And, that really, really believe this, inherently, and are looking at sort of how we include that in our process as well as include it in our product, right? That’s exactly what I’m trying to do at Obo.