#I always thought I was reasonably intelligent but I cannot solve this puzzle. there must be a creative solution that I'm missing

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

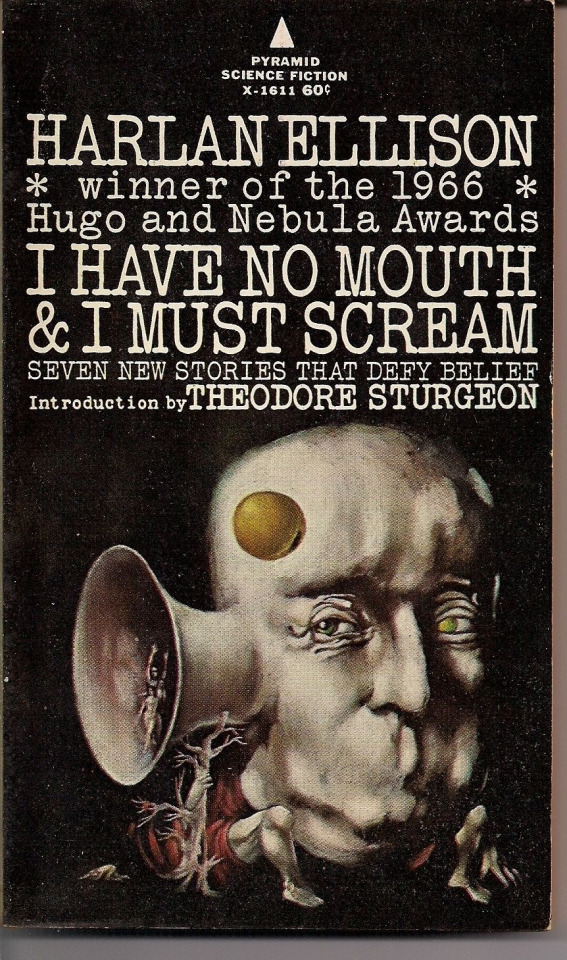

I Have No Mouth, And I Must Scream

…is the title of a Hugo-winning short story I just read. I’d heard the name for a while, gotten the gist of it, but for whatever reason I’d assumed it was a full on novel that I’d have to put proper time into, not a 13 page quickie made of psychological horror and fetid wordplay. This thing is dark, twisted, and probably one of the most influential stories I can think of, at least in terms of science fiction.

I suppose with such a short piece to divulge, it suits that the intro be similarly hastened. Shall I?

The cliffnotes version, although you can read the whole thing here if you’d like and it wont take too long. I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream, aside from being such an incredible title, is a tale of 5 individuals and the torture they undergo at the hands of AM, a supercomputer that has taken over the planet and extinguished all other human life on the face of the earth. For 109 years the fivesome- Ted, Benny, Gorrister, Nimdok, and Ellen- have been tortured, and altered, and kept perpetually alive by the machine, bleeding and dying and being corrupted over and over for its tepid amusement. AM significantly changed who they were- the pacifistic Gorrister turned an apathetic abuser, the brilliant scientist Benny rendered an ape-like creature with a…monster cock…for some reason (look the reasons are fucked up aight don’t wanna get into em), and the narrator, Ted, claims to be unaffected but his paranoia says otherwise.

After AM sends them on a particularly heinous journey as part of yet another controlled torment, Ted snaps into lucidity for the briefest of moments, taking a moment of AM’s distraction to (with Ellen’s help) kill the rest of his companions for good, ending their suffering in a way that AM cannot revert, and for this crime, AM finally transforms him into a horrific bloblike mess- the title being the final line of the story as he describes the disgusting, useless form he finds himself in- helpless to reply to the hatred AM has for him for all eternity.

This story, is fucked up, in case you hadn’t noticed.

(This is from a comic book adaptation, in case it wasn’t obvious)

It’s also exceptionally well written. The descriptions of everything ooze malice and pain, the vivid nightmare that is pseudo-reality for our five protagonists lovingly rendered in ink and blood. It’s the kind of story that lets me write sentences that silly without a hint of irony, which is always fun. It might literally be one of the first instances of “suffer porn”, though at the same time there’s a hint of hope to it- despite the perpetuity of Ted’s suffering, he ultimately does manage to “free” the other four, sacrificing himself by, ironically, surviving.

But aside from the suffer porn aspect, I’m certain this short story has to be the first of its kind in a fair few aspects- and if not the first, certainly the codifier. With it in mind that the tale was penned in 1966, it’s surely groundbreaking in its crystallisation of the fear of technology, of artificial intelligence, and ultimately, of apocalypse. The end of the world being caused by the folly of man wouldn’t have been a new concept, even in the 60s, but for our hubris to be repaid so fully, so viscerally, and in such a concentrated manner is surely a development of author Harlan Ellison’s own. I suspect that without I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream, we wouldn’t have Terminator, or System Shock, or The Matrix, or hell even Wargames - though perhaps that one might be for the best.

When reading it, I was also astonished to find how much of what I thought I knew about the story came instead from it’s 1995 adventure game adaptation of the same name. With Ellison’s involvement, it’s as close as you can get to an official expansion of the story, with perhaps its most iconic, non-titular monologue (pictured above) an exclusive to the additions. It’s an incredibly difficult game, designed to make you struggle in solving its puzzles, and screw it up repeatedly on the way through. Or at least, that’s my understanding, I never played it- read a let’s play instead, sucker, take that AM you cybertronic bitch.

I’d argue I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream holds up today, even as its ideas have filtered into the rest of popular culture. It still feels fresh despite its almost 55 years of publication, and despite the brutality described, it’s detached enough (and short enough) to be not too harrowing. Or perhaps I’m just too desensitized at this point. Hell if I know, but hell the characters do know.

(I think I’m very witty sometimes.)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Side note to The Women's Intuition

A more personal tangent…

I am a huge resistor as some of you know to definitive readings or speculation. Everything comes with an IF.

And more, though I rarely mention it, I loathe binary opposites. Gay vs trash. Especially when applied to characters. DFP vs smol. BAMF!John vs perfect loyal dog John. I can’t stand characters put into binary boxes because it makes them caricatures, not real and this unrelatable. It counters the text.

And binaries so often make for speculative leaps while ignoring data. It draws erroneous conclusions. “Must” should always take a back seat to “might”.

So for me to take such a hard line in a narrative reading of the text is for me not insignificant. It goes against impulse. It doesn’t let the writers hide behind for now a supposed and inferred unreliable narration. It draws a line in the sand I am usually very uncomfortable with.

I have always ALWAYS given these writers a massive benefit of the doubt. Perhaps more than necessary or warranted. Reading, as I do, a narrative end game - displayed by the surface text that the unobservant viewer doesn’t yet see. The rug pull. But also giving the writers latitude in how they play that game. And always knowing I may be wrong. Even though every instinct as a feminist queer Holmesian who knows their history tells me I’m not. Unless I have been royally baited and the text is lying to me and to boot is using women characters to tell that lie.

I am troubled by Moffat’s “doing the dishes” line on Thursday. It’s hugely problematic. It’s demeaning of everyone. Including himself. And yet I don’t need that either, even though in their historical context, it would be entirely congruent with ACD to frame these characters domestically without trivializing them.

And I’ll note that doing the dishes is historically women’s work. Trivialize that, you trivialize women. It’s the text book chicken and egg of misogyny: Women do dishes. Women are therefore trivial. Doing dishes is women’s work, therefore doing dishes must be trivial work. Therefore women are trivial. And should only do trivial work. Stay in the kitchen. Where you belong. Round and round and round it goes. For a momentary outburst it carries an immense historical weight. It is congruent with the reading of homophobia as the bastard child of misogyny. God forgive the man that ends up acting like a woman. Loving like a woman. Stuck at the kitchen sink like a woman. How trivial.

But dishes aside, however, I don’t trivialize this love at all. I see it written as High Romance. A kiss, or sex are not my benchmarks though I am uncomfortable with a desexualised queer reading of the text without very clear justification for it that fits these characters. I read these characters as ultimately epic. Their love story, canonically (a term I refuse to apply to anyone but ACD) as epic and queer. With a canonically textual and highly detailed domestic life to back it up told by an unreliable closeted narrator.

I am struck by the irony that while I don’t feel emotionally hurt at this juncture, others do. They feel driven mad, gaslighted, mistreated - cruelly so. I accept that for what it is. I understand it though I don’t feel that same strong emotional reaction. Perhaps as a queer woman I should.

But it strikes me as highly coincidental that the place I land in speculating on the narrative from a feminist, queer position matches the current fandom anxiety so perfectly. That the women characters are indeed potentially just like the fans. Wrong. And fools for thinking as they do.

And without wishing to seem uncaring, I don’t feel a strong impulse as an older fan to extend a caring hand to teenage fans. Perhaps I should. Mofftiss don’t intimidate me. I admire them but they are not my dads. They are my equals only a few years older than me. Talented, privileged, fortunate and very hard working - but ultimately my equals. They are human and capable of fucking up. As I am. Capable of being churlish or unkind.

I enjoy the fun on here but I am aware that I am nowhere close to being as emotionally invested as some others. I like the debate. The conversation. The analysis. But my happiness or sense of self in no way hangs on this show. This is simply an extension of the grand Sherlockian game from a queer perspective around one adaptation. And I enjoy the exchanges with bright, thoughtful, intelligent people who I literally don’t know - don’t even know their names or they mine - who like the game - the research, the speculation, the debate, the possibility of changing Sherlockian history. I appreciate the exchanges I have on here greatly.

I say all this for a very specific reason. Because that coincidence - that reading of women in the show and the alignment with fandom is not coincidence. Both are examples of an ongoing historic continuity. Of how women are treated in texts and in real life fandoms of texts. This is not me projecting. This is fact. I know categorically that i am not overly emotional. Hysterical. As if emotions are something to be ashamed of! If anything I’m not emotional enough. I find myself concluding a defense of a fandom that I often feel little emotional identity with and from which I feel generationally apart. And I cannot deny that there is something way off base in how others in this fandom are treated. Historically congruent and way off. And I admit I have sided with Mofftiss more often than not.

I am more than up for the debate. I am happy to be proven wrong or shown a way to break the binary opposition I see in the textual narrative. Bring it on. Show me I am wrong. I have never been one on here to shy away from saying oh, I made a mistake or I misread or misunderstood or misremembered. Prove me wrong and I will happily concede the point.

I am very very far from the caricature fan Moffat imagines. I am very very like him in many ways. But as a queer woman I am different from him. And if my read is wrong I want to know why. I want to know why I should let go of my own reading to serve his. Because my reading makes more sense of the text as he has written it. He, not Gatiss, is the extravagantly Romantic writer here.

I don’t know what my benchmark is for TFP. I am open to being surprised. But there is a binary I find in this text that is highly problematic. Because it is more than queerbaiting. It casts women in a very dodgy light unless the narrative follows through to an endgame that proves them right. (Look at TAB for god’s sake. That episode which I loved and was critiqued at the time is so very problematic in not only its treatment of women but of Sherlock himself if the narrative doesn’t deliver a queer endgame.)

I want him to prove me wrong. I really do. Not because my feelings are hurt but because I want this story to be something other than the same old crap women and queer people have put up with for years. I want him to dare to go there. To follow through on the narrative he has written. To have an ending worthy of it. Worthy of all these characters.

Because I want it to be good.

If there is an option C it will have to be a really good one. It will have to be a very compelling read. I have hope. Genuinely. But I am under no illusion that this narrative is on perilous grounds. That this show is potentially going to go way down in my estimations.

And rather than saying, “these writers are so clever” I will have to change course and say, “I was wrong. This really is nothing new. It’s a bit not good.”

And I will potentially then also conclude that how i and so many others read this story - queerly - is actually the *more* clever solution.

I hope I am proved wrong. I hope they surprise the life out of me. I would happily concede the point. I would like the writers, for me, for us all to win this game in the end. I don’t want progress to be on the losing side. And boy do we need some progress in this current climate where progress is under such extreme threat.

A lot hangs on TFP. Inside the narrative and without. But in the end all I want is it to be a little sign of hope in the world. A story of resistance. Of change. Of progress. That the goodies will win. Because they must win. There is no if about that. The alternative is so bleak right now. I want a story where my heroes win and I win too. Where I get to feel just a little bit heroic. I’d like that for Mofftiss too.

There’s nothing trivial about me wanting people like me to be heroic. That’s the power of stories. They don’t have to be real to be true. They change us. They shape profoundly how we view ourselves. There is nothing trivial about it.

And let’s be honest. If all that lay ahead for Sherlock and John was that they spent their days washing dishes and living in peace and solving puzzles in the safety of their own home, with someone who loves them, to grow old with, to walk safely down the street without threat of violence or hate - that’s not nothing. It’s a darn lot more than many women and queer people have gotten or still get. But they’d be lucky to have it. Anyone would.

We will see.

167 notes

·

View notes

Text

'A Perfect and Beautiful Machine': What Darwin's Theory of Evolution Reveals About Artificial Intelligence

Charles Darwin and Alan Turing, in their different ways, both homed in on the same idea: the existence of competence without comprehension

Some of the greatest, most revolutionary advances in science have been given their initial expression in attractively modest terms, with no fanfare.

Charles Darwin managed to compress his entire theory into a single summary paragraph that a layperson can readily follow.

Francis Crick and James Watson closed their epoch-making paper on the structure of DNA with a single deliciously diffident sentence. ("It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material.")

And Alan Turing created a new world of science and technology, setting the stage for solving one of the most baffling puzzles remaining to science, the mind-body problem, with an even shorter declarative sentence in the middle of his 1936 paper on computable numbers:

It is possible to invent a single machine which can be used to compute any computable sequence.

Turing didn't just intuit that this remarkable feat was possible; he showed exactly how to make such a machine. With that demonstration the computer age was born. It is important to remember that there were entities called computers before Turing came up with his idea, but they were people, clerical workers with enough mathematical skill, patience, and pride in their work to generate reliable results of hours and hours of computation, day in and day out. Many of them were women.

Thousands of them were employed in engineering and commerce, and in the armed forces and elsewhere, calculating tables for use in navigation, gunnery and other such technical endeavors. A good way of understanding Turing's revolutionary idea about computation is to put it in juxtaposition with Darwin's about evolution. The pre-darwinian world was held together not by science but by tradition: All things in the universe, from the most exalted ("man") to the most humble (the ant, the pebble, the raindrop) were creations of a still more exalted thing, God, an omnipotent and omniscient intelligent creator -- who bore a striking resemblance to the second-most exalted thing. Call this the trickle-down theory of creation. Darwin replaced it with the bubble-up theory of creation. One of Darwin's nineteenth-century critics, Robert Beverly MacKenzie, put it vividly:

In the theory with which we have to deal, Absolute Ignorance is the artificer; so that we may enunciate as the fundamental principle of the whole system, that, in order to make a perfect and beautiful machine, it is not requisite to know how to make it. This proposition will be found, on careful examination, to express, in condensed form, the essential purport of the Theory, and to express in a few words all Mr. Darwin's meaning; who, by a strange inversion of reasoning, seems to think Absolute Ignorance fully qualified to take the place of Absolute Wisdom in all the achievements of creative skill.

It was, indeed, a strange inversion of reasoning. To this day many people cannot get their heads around the unsettling idea that a purposeless, mindless process can crank away through the eons, generating ever more subtle, efficient, and complex organisms without having the slightest whiff of understanding of what it is doing.

Turing's idea was a similar -- in fact remarkably similar -- strange inversion of reasoning. The Pre-Turing world was one in which computers were people, who had to understand mathematics in order to do their jobs. Turing realized that this was just not necessary: you could take the tasks they performed and squeeze out the last tiny smidgens of understanding, leaving nothing but brute, mechanical actions.

In order to be a perfect and beautiful computing machine, it is not requisite to know what arithmetic is.

What Darwin and Turing had both discovered, in their different ways, was the existence of competence without comprehension. This inverted the deeply plausible assumption that comprehension is in fact the source of all advanced competence. Why, after all, do we insist on sending our children to school, and why do we frown on the old-fashioned methods of rote learning? We expect our children's growing competence to flow from their growing comprehension. The motto of modern education might be: "Comprehend in order to be competent." For us members of H. sapiens, this is almost always the right way to look at, and strive for, competence. I suspect that this much-loved principle of education is one of the primary motivators of skepticism about both evolution and its cousin in Turing's world, artificial intelligence.

The very idea that mindless mechanicity can generate human-level -- or divine level! -- competence strikes many as philistine, repugnant, an insult to our minds, and the mind of God.

Consider how Turing went about his proof. He took human computers as his model. There they sat at their desks, doing one simple and highly reliable step after another, checking their work, writing down the intermediate results instead of relying on their memories, consulting their recipes as often as they needed, turning what at first might appear a daunting task into a routine they could almost do in their sleep. Turing systematically broke down the simple steps into even simpler steps, removing all vestiges of discernment or comprehension. Did a human computer have difficulty telling the number 99999999999 from the number 9999999999? Then break down the perceptual problem of recognizing the number into simpler problems, distributing easier, stupider acts of discrimination over multiple steps. He thus prepared an inventory of basic building blocks from which to construct the universal algorithm that could execute any other algorithm. He showed how that algorithm would enable a (human) computer to compute any function, and noted that:

The behavior of the computer at any moment is determined by the symbols which he is observing and his "state of mind" at that moment. We may suppose that there is a bound B to the number of symbols or squares which the computer can observe at one moment. If he wishes to observe more, he must use successive observations. ... The operation actually performed is determined ... by the state of mind of the computer and the observed symbols. In particular, they determine the state of mind of the computer after the operation is carried out.

He then noted, calmly:

We may now construct a machine to do the work of this computer.

Right there we see the reduction of all possible computation to a mindless process. We can start with the simple building blocks Turing had isolated, and construct layer upon layer of more sophisticated computation, restoring, gradually, the intelligence Turing had so deftly laundered out of the practices of human computers.

But what about the genius of Turing, and of later, lesser programmers, whose own intelligent comprehension was manifestly the source of the designs that can knit Turing's mindless building blocks into useful competences? Doesn't this dependence just re-introduce the trickle-down perspective on intelligence, with Turing in the God role? No less a thinker than Roger Penrose has expressed skepticism about the possibility that artificial intelligence could be the fruit of nothing but mindless algorithmic processes.

I am a strong believer in the power of natural selection. But I do not see how natural selection, in itself, can evolve algorithms which could have the kind of conscious judgements of the validity of other algorithms that we seem to have.

He goes on to admit:

To my way of thinking there is still something mysterious about evolution, with its apparent 'groping' towards some future purpose. Things at least seem to organize themselves somewhat better than they 'ought' to, just on the basis of blind-chance evolution and natural selection.

Indeed, a single cascade of natural selection events, occurring over even billions of years, would seem unlikely to be able to create a string of zeroes and ones that, once read by a digital computer, would be an "algorithm" for "conscious judgments." But as Turing fully realized, there was nothing to prevent the process of evolution from copying itself on many scales, of mounting discernment and judgment. The recursive step that got the ball rolling -- designing a computer that could mimic any other computer -- could itself be reiterated, permitting specific computers to enhance their own powers by redesigning themselves, leaving their original designer far behind. Already in "Computing Machinery and Intelligence," his classic paper in Mind, 1950, he recognized that there was no contradiction in the concept of a (non-human) computer that could learn.

The idea of a learning machine may appear paradoxical to some readers. How can the rules of operation of the machine change? They should describe completely how the machine will react whatever its history might be, whatever changes it might undergo. The rules are thus quite time-invariant. This is quite true. The explanation of the paradox is that the rules which get changed in the learning process are of a rather less pretentious kind, claiming only an ephemeral validity. The reader may draw a parallel with the Constitution of the United States.

He saw clearly that all the versatility and self-modifiability of human thought -- learning and re-evaluation and, language and problem-solving, for instance -- could in principle be constructed out of these building blocks. Call this the bubble-up theory of mind, and contrast it with the various trickle-down theories of mind, by thinkers from René Descartes to John Searle (and including, notoriously, Kurt Gödel, whose proof was the inspiration for Turing's work) that start with human consciousness at its most reflective, and then are unable to unite such magical powers with the mere mechanisms of human bodies and brains.

Turing, like Darwin, broke down the mystery of intelligence (or Intelligent Design) into what we might call atomic steps of dumb happenstance, which, when accumulated by the millions, added up to a sort of pseudo-intelligence.

The Central Processing Unit of a computer doesn't really know what arithmetic is, or understand what addition is, but it "understands" the "command" to add two numbers and put their sum in a register -- in the minimal sense that it reliably adds when called upon to add and puts the sum in the right place. Let's say it sorta understands addition. A few levels higher, the operating system doesn't really understand that it is checking for errors of transmission and fixing them but it sorta understands this, and reliably does this work when called upon. A few further levels higher, when the building blocks are stacked up by the billions and trillions, the chess-playing program doesn't really understand that its queen is in jeopardy, but it sorta understands this, and IBM's Watson on Jeopardy sorta understands the questions it answers.

Why indulge in this "sorta" talk? Because when we analyze -- or synthesize -- this stack of ever more competent levels, we need to keep track of two facts about each level: what it is and what it does. What it is can be described in terms of the structural organization of the parts from which it is made -- so long as we can assume that the parts function as they are supposed to function. What it does is some (cognitive) function that it (sorta) performs -- well enough so that at the next level up, we can make the assumption that we have in our inventory a smarter building block that performs just that function -- sorta, good enough to use.

This is the key to breaking the back of the mind-bogglingly complex question of how a mind could ever be composed of material mechanisms. What we might call the sorta operator is, in cognitive science, the parallel of Darwin's gradualism in evolutionary processes. Before there were bacteria there were sorta bacteria, and before there were mammals there were sorta mammals and before there were dogs there were sorta dogs, and so forth. We need Darwin's gradualism to explain the huge difference between an ape and an apple, and we need Turing's gradualism to explain the huge difference between a humanoid robot and hand calculator.

The ape and the apple are made of the same basic ingredients, differently structured and exploited in a many-level cascade of different functional competences. There is no principled dividing line between a sorta ape and an ape. The humanoid robot and the hand calculator are both made of the same basic, unthinking, unfeeling Turing-bricks, but as we compose them into larger, more competent structures, which then become the elements of still more competent structures at higher levels, we eventually arrive at parts so (sorta) intelligent that they can be assembled into competences that deserve to be called comprehending.

We use the intentional stance to keep track of the beliefs and desires (or "beliefs" and "desires" or sorta beliefs and sorta desires) of the (sorta-)rational agents at every level from the simplest bacterium through all the discriminating, signaling, comparing, remembering circuits that compose the brains of animals from starfish to astronomers.

There is no principled line above which true comprehension is to be found -- even in our own case. The small child sorta understands her own sentence "Daddy is a doctor," and I sorta understand "E=mc2." Some philosophers resist this anti-essentialism: either you believe that snow is white or you don't; either you are conscious or you aren't; nothing counts as an approximation of any mental phenomenon -- it's all or nothing. And to such thinkers, the powers of minds are insoluble mysteries because they are "perfect," and perfectly unlike anything to be found in mere material mechanisms.

We still haven't arrived at "real" understanding in robots, but we are getting closer. That, at least, is the conviction of those of us inspired by Turing's insight. The trickle-down theorists are sure in their bones that no amount of further building will ever get us to the real thing. They think that a Cartesian res cogitans, a thinking thing, cannot be constructed out of Turing's building blocks. And creationists are similarly sure in their bones that no amount of Darwinian shuffling and copying and selecting could ever arrive at (real) living things. They are wrong, but one can appreciate the discomfort that motivates their conviction.

Turing's strange inversion of reason, like Darwin's, goes against the grain of millennia of earlier thought. If the history of resistance to Darwinian thinking is a good measure, we can expect that long into the future, long after every triumph of human thought has been matched or surpassed by "mere machines," there will still be thinkers who insist that the human mind works in mysterious ways that no science can comprehend.

https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2012/06/-a-perfect-and-beautiful-machine-what-darwins-theory-of-evolution-reveals-about-artificial-intelligence/258829/

0 notes

Text

Attribution is Awesome! Here’s Why It’s Terrible

As I recently wrote in A Tale of Attribution Woe (read that beginner-post first if the idea of attribution is fairly new to you), understanding attribution well (note, I didn’t say “figuring it out”) is an essential part of any digital marketing strategy. Unfortunately, it is also an evolving industry… which means there is still a lot of guesswork and change involved.

Attribution Ditch #1: Attribution Ignorance

When it comes to attribution, I believe there are two ditches that need to be avoided by marketers. The first ditch is the more obvious one: it is the ditch of attribution ignorance. That is, the difficulties of attribution are crucial to be aware of when setting budgets and assigning ROI properly, and it is no longer an excuse to ignore attribution. Whether it be cross-channel or cross-device, we need to get better at identifying how different channels impact our client sales. Going beyond a simplistic last click model in our understanding is essential.

In some ways, I would argue that this ditch has increasingly been called out and warned against successfully in our industry. There is still a long way to go, but attribution-awareness has been significantly increased from even a couple of years ago, and I find that even clients are hungry to unpack the puzzle of the attribution enigma in their accounts.

So we veer away from the ditch of attribution-ignorance… and head directly across the road into the ditch of attribution-arrogance.

Attribution Ditch #2: Attribution Arrogance

Whereas attribution-ignorance is undervaluing the knowledge that attribution can bring to a client account, attribution-arrogance is over-estimating the knowledge that can be gained. It looks at a simplistic model included in Google Analytics, assigns X % of value to each source, and confidently sends a report to the client, “thus hath the mines of mystery been plumbed, and thus shalt the budget be setteth.”

This is a ditch because it communicates to the client that attribution is simplistic, requiring only a specific formula (which BTW, the agency has clearly figured out that perfect formula </sarcasm>), in order for infallible ROI measuring awesomeness to be grasped.

Attribution’s Fatal Flaw

However, there is in my belief, a significant weakness to attribution that must be understood in order to keep our accounts out of either ditch and squarely in the center of the road. This center of the road, by the way, is always where the best marketers have proven themselves. It is the immaculate balance of both data and human-gut-intelligence-prowess. A good marketer uses data. A great marketer uses data to take action on what she believes to be true that has not yet been proven yet (and sometimes, can never be proven).

Regardless, let’s get back to the weakness of attribution. The glaring weakness of attribution is none other than our inability to accurately track human emotions.

What I mean by that, is that attribution will always be limited to the data it collects, when the actual decision made in a sale happens in the mind.

Allow me to illustrate this with one of my favorite characters (he was my favorite long before he was made popular by Benedict Cumberbatch!).

Sherlock Holmes is a master of deducing facts in order to solve a case, but not every fact and not every deduction holds equal value in the resolution of a case.

For instance, he may discover fibers on the floor that lead him down a mental path, and then he might interview a witness who lies about a key piece of evidence, and then this might cause him to visit the moor itself whereby he will put the finishing touches on the case.

Yes, attribution can answer the question: “which factual interactions led Sherlock Holmes to solve the case.” But attribution can NEVER properly weight those. I do realize never is a strong word, but I stand by it.

For instance, analytics of event facts and user behavior data cannot reveal the fact that it was the witness lying that caused Holmes the *most suspicion*, which led him to pursue the case more intentionally and thus visit the moor, leading to the resolution. Without Holmes (or, Watson for that matter, or really Sir Arthur Conan Doyle) actually telling us what went on in his head, we cannot know his intentions and how they were impacted by each interaction.

The weakness in using this as an example is that we can see into the head of Holmes, so we are brought into the decision. This is not the case with online buyers! While you can track user behavior on your site, and you can identify and fire various events to identify who did what, when on your site, you still can never actually know which channel caused the most “credit” for a sale in the mind of the user.

This is absolutely crucial because we analyze attribution data in a percentage model. This model doles out equal percentages of credit to the channels in the middle of a funnel, that model doles out 100% of the credit to the last channel to send traffic, and so on. However, these are doling out credit as percentages based solely on TIMING OF SESSIONS, and not on how we as humans actually make decisions… with emotion, with logic, with reason, with desire.

At the very least, one change that needs to happen immediately is less bold-faced ROI claims from attribution and more honest communication with clients into the actual state of things. Be less concerned with finding a 100% perfect attribution model, and more concerned with diving deep into a partnership built on trust that will allow you and the client to adapt over time as you continue to experiment and tweak their attribution model based upon source interactions over time.

So to close, as we think about attribution I’d like to warn us not to run from the one ditch into the other. Attribution is evolving in digital marketing (woohoo!), but our understanding of it needs to evolve as well.

We need to stop simply asking “how were the sources arranged in this transaction” (that’s a great place to start) and instead begin asking immediately after the first question, “what can I learn about my customer’s emotional orientation towards my brand in each channel.”

Also, frankly, we just need to be okay with not having attribution 100% figured out. We can’t know it perfectly. We can never know it perfectly. Take a deep breath, repeat that to yourself, and then get to work trying to get as close to perfect as possible in your client.

I would like to leave you with a resource for further study. After I wrote my Attribution and the Cows post on ZATO (linked above), I was contacted (and helpfully corrected) by Peter O’Neill of L3 Analytics. During our twitter conversation, he pointed my way to a presentation he gave way back in 2012 of the issues with attribution (I had already written this post before that conversation). I scrolled through the slides and thought they were some of the best work on attribution I’ve ever seen, so I wanted to share them with you here.

from RSSMix.com Mix ID 8217493 http://www.ppchero.com/attribution-is-awesome-heres-why-its-terrible/

0 notes

Text

Attribution is Awesome! Here’s Why It’s Terrible

As I recently wrote in A Tale of Attribution Woe (read that beginner-post first if the idea of attribution is fairly new to you), understanding attribution well (note, I didn’t say “figuring it out”) is an essential part of any digital marketing strategy. Unfortunately, it is also an evolving industry… which means there is still a lot of guesswork and change involved.

Attribution Ditch #1: Attribution Ignorance

When it comes to attribution, I believe there are two ditches that need to be avoided by marketers. The first ditch is the more obvious one: it is the ditch of attribution ignorance. That is, the difficulties of attribution are crucial to be aware of when setting budgets and assigning ROI properly, and it is no longer an excuse to ignore attribution. Whether it be cross-channel or cross-device, we need to get better at identifying how different channels impact our client sales. Going beyond a simplistic last click model in our understanding is essential.

In some ways, I would argue that this ditch has increasingly been called out and warned against successfully in our industry. There is still a long way to go, but attribution-awareness has been significantly increased from even a couple of years ago, and I find that even clients are hungry to unpack the puzzle of the attribution enigma in their accounts.

So we veer away from the ditch of attribution-ignorance… and head directly across the road into the ditch of attribution-arrogance.

Attribution Ditch #2: Attribution Arrogance

Whereas attribution-ignorance is undervaluing the knowledge that attribution can bring to a client account, attribution-arrogance is over-estimating the knowledge that can be gained. It looks at a simplistic model included in Google Analytics, assigns X % of value to each source, and confidently sends a report to the client, “thus hath the mines of mystery been plumbed, and thus shalt the budget be setteth.”

This is a ditch because it communicates to the client that attribution is simplistic, requiring only a specific formula (which BTW, the agency has clearly figured out that perfect formula </sarcasm>), in order for infallible ROI measuring awesomeness to be grasped.

Attribution’s Fatal Flaw

However, there is in my belief, a significant weakness to attribution that must be understood in order to keep our accounts out of either ditch and squarely in the center of the road. This center of the road, by the way, is always where the best marketers have proven themselves. It is the immaculate balance of both data and human-gut-intelligence-prowess. A good marketer uses data. A great marketer uses data to take action on what she believes to be true that has not yet been proven yet (and sometimes, can never be proven).

Regardless, let’s get back to the weakness of attribution. The glaring weakness of attribution is none other than our inability to accurately track human emotions.

What I mean by that, is that attribution will always be limited to the data it collects, when the actual decision made in a sale happens in the mind.

Allow me to illustrate this with one of my favorite characters (he was my favorite long before he was made popular by Benedict Cumberbatch!).

Sherlock Holmes is a master of deducing facts in order to solve a case, but not every fact and not every deduction holds equal value in the resolution of a case.

For instance, he may discover fibers on the floor that lead him down a mental path, and then he might interview a witness who lies about a key piece of evidence, and then this might cause him to visit the moor itself whereby he will put the finishing touches on the case.

Yes, attribution can answer the question: “which factual interactions led Sherlock Holmes to solve the case.” But attribution can NEVER properly weight those. I do realize never is a strong word, but I stand by it.

For instance, analytics of event facts and user behavior data cannot reveal the fact that it was the witness lying that caused Holmes the *most suspicion*, which led him to pursue the case more intentionally and thus visit the moor, leading to the resolution. Without Holmes (or, Watson for that matter, or really Sir Arthur Conan Doyle) actually telling us what went on in his head, we cannot know his intentions and how they were impacted by each interaction.

The weakness in using this as an example is that we can see into the head of Holmes, so we are brought into the decision. This is not the case with online buyers! While you can track user behavior on your site, and you can identify and fire various events to identify who did what, when on your site, you still can never actually know which channel caused the most “credit” for a sale in the mind of the user.

This is absolutely crucial because we analyze attribution data in a percentage model. This model doles out equal percentages of credit to the channels in the middle of a funnel, that model doles out 100% of the credit to the last channel to send traffic, and so on. However, these are doling out credit as percentages based solely on TIMING OF SESSIONS, and not on how we as humans actually make decisions… with emotion, with logic, with reason, with desire.

At the very least, one change that needs to happen immediately is less bold-faced ROI claims from attribution and more honest communication with clients into the actual state of things. Be less concerned with finding a 100% perfect attribution model, and more concerned with diving deep into a partnership built on trust that will allow you and the client to adapt over time as you continue to experiment and tweak their attribution model based upon source interactions over time.

So to close, as we think about attribution I’d like to warn us not to run from the one ditch into the other. Attribution is evolving in digital marketing (woohoo!), but our understanding of it needs to evolve as well.

We need to stop simply asking “how were the sources arranged in this transaction” (that’s a great place to start) and instead begin asking immediately after the first question, “what can I learn about my customer’s emotional orientation towards my brand in each channel.”

Also, frankly, we just need to be okay with not having attribution 100% figured out. We can’t know it perfectly. We can never know it perfectly. Take a deep breath, repeat that to yourself, and then get to work trying to get as close to perfect as possible in your client.

I would like to leave you with a resource for further study. After I wrote my Attribution and the Cows post on ZATO (linked above), I was contacted (and helpfully corrected) by Peter O’Neill of L3 Analytics. During our twitter conversation, he pointed my way to a presentation he gave way back in 2012 of the issues with attribution (I had already written this post before that conversation). I scrolled through the slides and thought they were some of the best work on attribution I’ve ever seen, so I wanted to share them with you here.

from RSSMix.com Mix ID 8217493 http://www.ppchero.com/attribution-is-awesome-heres-why-its-terrible/

0 notes

Text

Attribution is Awesome! Here’s Why It’s Terrible

As I recently wrote in A Tale of Attribution Woe (read that beginner-post first if the idea of attribution is fairly new to you), understanding attribution well (note, I didn’t say “figuring it out”) is an essential part of any digital marketing strategy. Unfortunately, it is also an evolving industry… which means there is still a lot of guesswork and change involved.

Attribution Ditch #1: Attribution Ignorance

When it comes to attribution, I believe there are two ditches that need to be avoided by marketers. The first ditch is the more obvious one: it is the ditch of attribution ignorance. That is, the difficulties of attribution are crucial to be aware of when setting budgets and assigning ROI properly, and it is no longer an excuse to ignore attribution. Whether it be cross-channel or cross-device, we need to get better at identifying how different channels impact our client sales. Going beyond a simplistic last click model in our understanding is essential.

In some ways, I would argue that this ditch has increasingly been called out and warned against successfully in our industry. There is still a long way to go, but attribution-awareness has been significantly increased from even a couple of years ago, and I find that even clients are hungry to unpack the puzzle of the attribution enigma in their accounts.

So we veer away from the ditch of attribution-ignorance… and head directly across the road into the ditch of attribution-arrogance.

Attribution Ditch #2: Attribution Arrogance

Whereas attribution-ignorance is undervaluing the knowledge that attribution can bring to a client account, attribution-arrogance is over-estimating the knowledge that can be gained. It looks at a simplistic model included in Google Analytics, assigns X % of value to each source, and confidently sends a report to the client, “thus hath the mines of mystery been plumbed, and thus shalt the budget be setteth.”

This is a ditch because it communicates to the client that attribution is simplistic, requiring only a specific formula (which BTW, the agency has clearly figured out that perfect formula </sarcasm>), in order for infallible ROI measuring awesomeness to be grasped.

Attribution’s Fatal Flaw

However, there is in my belief, a significant weakness to attribution that must be understood in order to keep our accounts out of either ditch and squarely in the center of the road. This center of the road, by the way, is always where the best marketers have proven themselves. It is the immaculate balance of both data and human-gut-intelligence-prowess. A good marketer uses data. A great marketer uses data to take action on what she believes to be true that has not yet been proven yet (and sometimes, can never be proven).

Regardless, let’s get back to the weakness of attribution. The glaring weakness of attribution is none other than our inability to accurately track human emotions.

What I mean by that, is that attribution will always be limited to the data it collects, when the actual decision made in a sale happens in the mind.

Allow me to illustrate this with one of my favorite characters (he was my favorite long before he was made popular by Benedict Cumberbatch!).

Sherlock Holmes is a master of deducing facts in order to solve a case, but not every fact and not every deduction holds equal value in the resolution of a case.

For instance, he may discover fibers on the floor that lead him down a mental path, and then he might interview a witness who lies about a key piece of evidence, and then this might cause him to visit the moor itself whereby he will put the finishing touches on the case.

Yes, attribution can answer the question: “which factual interactions led Sherlock Holmes to solve the case.” But attribution can NEVER properly weight those. I do realize never is a strong word, but I stand by it.

For instance, analytics of event facts and user behavior data cannot reveal the fact that it was the witness lying that caused Holmes the *most suspicion*, which led him to pursue the case more intentionally and thus visit the moor, leading to the resolution. Without Holmes (or, Watson for that matter, or really Sir Arthur Conan Doyle) actually telling us what went on in his head, we cannot know his intentions and how they were impacted by each interaction.

The weakness in using this as an example is that we can see into the head of Holmes, so we are brought into the decision. This is not the case with online buyers! While you can track user behavior on your site, and you can identify and fire various events to identify who did what, when on your site, you still can never actually know which channel caused the most “credit” for a sale in the mind of the user.

This is absolutely crucial because we analyze attribution data in a percentage model. This model doles out equal percentages of credit to the channels in the middle of a funnel, that model doles out 100% of the credit to the last channel to send traffic, and so on. However, these are doling out credit as percentages based solely on TIMING OF SESSIONS, and not on how we as humans actually make decisions… with emotion, with logic, with reason, with desire.

At the very least, one change that needs to happen immediately is less bold-faced ROI claims from attribution and more honest communication with clients into the actual state of things. Be less concerned with finding a 100% perfect attribution model, and more concerned with diving deep into a partnership built on trust that will allow you and the client to adapt over time as you continue to experiment and tweak their attribution model based upon source interactions over time.

So to close, as we think about attribution I’d like to warn us not to run from the one ditch into the other. Attribution is evolving in digital marketing (woohoo!), but our understanding of it needs to evolve as well.

We need to stop simply asking “how were the sources arranged in this transaction” (that’s a great place to start) and instead begin asking immediately after the first question, “what can I learn about my customer’s emotional orientation towards my brand in each channel.”

Also, frankly, we just need to be okay with not having attribution 100% figured out. We can’t know it perfectly. We can never know it perfectly. Take a deep breath, repeat that to yourself, and then get to work trying to get as close to perfect as possible in your client.

I would like to leave you with a resource for further study. After I wrote my Attribution and the Cows post on ZATO (linked above), I was contacted (and helpfully corrected) by Peter O’Neill of L3 Analytics. During our twitter conversation, he pointed my way to a presentation he gave way back in 2012 of the issues with attribution (I had already written this post before that conversation). I scrolled through the slides and thought they were some of the best work on attribution I’ve ever seen, so I wanted to share them with you here.

from RSSMix.com Mix ID 8217493 http://www.ppchero.com/attribution-is-awesome-heres-why-its-terrible/

0 notes

Text

Attribution is Awesome! Here’s Why It’s Terrible

As I recently wrote in A Tale of Attribution Woe (read that beginner-post first if the idea of attribution is fairly new to you), understanding attribution well (note, I didn’t say “figuring it out”) is an essential part of any digital marketing strategy. Unfortunately, it is also an evolving industry… which means there is still a lot of guesswork and change involved.

Attribution Ditch #1: Attribution Ignorance

When it comes to attribution, I believe there are two ditches that need to be avoided by marketers. The first ditch is the more obvious one: it is the ditch of attribution ignorance. That is, the difficulties of attribution are crucial to be aware of when setting budgets and assigning ROI properly, and it is no longer an excuse to ignore attribution. Whether it be cross-channel or cross-device, we need to get better at identifying how different channels impact our client sales. Going beyond a simplistic last click model in our understanding is essential.

In some ways, I would argue that this ditch has increasingly been called out and warned against successfully in our industry. There is still a long way to go, but attribution-awareness has been significantly increased from even a couple of years ago, and I find that even clients are hungry to unpack the puzzle of the attribution enigma in their accounts.

So we veer away from the ditch of attribution-ignorance… and head directly across the road into the ditch of attribution-arrogance.

Attribution Ditch #2: Attribution Arrogance

Whereas attribution-ignorance is undervaluing the knowledge that attribution can bring to a client account, attribution-arrogance is over-estimating the knowledge that can be gained. It looks at a simplistic model included in Google Analytics, assigns X % of value to each source, and confidently sends a report to the client, “thus hath the mines of mystery been plumbed, and thus shalt the budget be setteth.”

This is a ditch because it communicates to the client that attribution is simplistic, requiring only a specific formula (which BTW, the agency has clearly figured out that perfect formula </sarcasm>), in order for infallible ROI measuring awesomeness to be grasped.

Attribution’s Fatal Flaw

However, there is in my belief, a significant weakness to attribution that must be understood in order to keep our accounts out of either ditch and squarely in the center of the road. This center of the road, by the way, is always where the best marketers have proven themselves. It is the immaculate balance of both data and human-gut-intelligence-prowess. A good marketer uses data. A great marketer uses data to take action on what she believes to be true that has not yet been proven yet (and sometimes, can never be proven).

Regardless, let’s get back to the weakness of attribution. The glaring weakness of attribution is none other than our inability to accurately track human emotions.

What I mean by that, is that attribution will always be limited to the data it collects, when the actual decision made in a sale happens in the mind.

Allow me to illustrate this with one of my favorite characters (he was my favorite long before he was made popular by Benedict Cumberbatch!).

Sherlock Holmes is a master of deducing facts in order to solve a case, but not every fact and not every deduction holds equal value in the resolution of a case.

For instance, he may discover fibers on the floor that lead him down a mental path, and then he might interview a witness who lies about a key piece of evidence, and then this might cause him to visit the moor itself whereby he will put the finishing touches on the case.

Yes, attribution can answer the question: “which factual interactions led Sherlock Holmes to solve the case.” But attribution can NEVER properly weight those. I do realize never is a strong word, but I stand by it.

For instance, analytics of event facts and user behavior data cannot reveal the fact that it was the witness lying that caused Holmes the *most suspicion*, which led him to pursue the case more intentionally and thus visit the moor, leading to the resolution. Without Holmes (or, Watson for that matter, or really Sir Arthur Conan Doyle) actually telling us what went on in his head, we cannot know his intentions and how they were impacted by each interaction.

The weakness in using this as an example is that we can see into the head of Holmes, so we are brought into the decision. This is not the case with online buyers! While you can track user behavior on your site, and you can identify and fire various events to identify who did what, when on your site, you still can never actually know which channel caused the most “credit” for a sale in the mind of the user.

This is absolutely crucial because we analyze attribution data in a percentage model. This model doles out equal percentages of credit to the channels in the middle of a funnel, that model doles out 100% of the credit to the last channel to send traffic, and so on. However, these are doling out credit as percentages based solely on TIMING OF SESSIONS, and not on how we as humans actually make decisions… with emotion, with logic, with reason, with desire.

At the very least, one change that needs to happen immediately is less bold-faced ROI claims from attribution and more honest communication with clients into the actual state of things. Be less concerned with finding a 100% perfect attribution model, and more concerned with diving deep into a partnership built on trust that will allow you and the client to adapt over time as you continue to experiment and tweak their attribution model based upon source interactions over time.

So to close, as we think about attribution I’d like to warn us not to run from the one ditch into the other. Attribution is evolving in digital marketing (woohoo!), but our understanding of it needs to evolve as well.

We need to stop simply asking “how were the sources arranged in this transaction” (that’s a great place to start) and instead begin asking immediately after the first question, “what can I learn about my customer’s emotional orientation towards my brand in each channel.”

Also, frankly, we just need to be okay with not having attribution 100% figured out. We can’t know it perfectly. We can never know it perfectly. Take a deep breath, repeat that to yourself, and then get to work trying to get as close to perfect as possible in your client.

I would like to leave you with a resource for further study. After I wrote my Attribution and the Cows post on ZATO (linked above), I was contacted (and helpfully corrected) by Peter O’Neill of L3 Analytics. During our twitter conversation, he pointed my way to a presentation he gave way back in 2012 of the issues with attribution (I had already written this post before that conversation). I scrolled through the slides and thought they were some of the best work on attribution I’ve ever seen, so I wanted to share them with you here.

from RSSMix.com Mix ID 8217493 http://www.ppchero.com/attribution-is-awesome-heres-why-its-terrible/

0 notes