#Hunstanton school

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Ask request (to help fill the inbox) - song number 23, for either Dando or Galex ♥

Hunstanton Pier by Deaf Havana

It was always strange coming home. Daniel had thought that with time it would get better yet with every passing year, his hometown just became a reminder of everything he had left behind. Every corner store was filled with the ghost of memories of childhood. All the streets were filled with people he didn't recognise anymore but they recognised him. The first time someone he went to school with had stopped him, Daniel hadn't recognised them. They'd beamed at him, reminiscing about jokes Daniel used to make and the dances they'd been too that were nothing but a vague memory for Daniel now. Her kids had been standing beside her, one shyly tucked behind her legs, and the other playing on his switch as if he wanted to be anywhere but here. The encounter had left Daniel unmoored somehow. It had made him face the what if's and the people he had left behind. He never felt the gap between him and his hometown until that moment when he realised that everyone had grown. They had grown and moved on and started families, and Daniel....Daniel still felt as if he was stuck at the same point that he was at when he had left to chase his dreams. "You know that kid you used to play with? The one with the red hair?", his mum had said one day when he had rung home while sitting in a hotel room half way around the world, "Steven was his name. Well, he passed away this week" The news had broken something in Daniel. It had stolen one of his last ties to the place he desperately clung to because Steven had been stuck just like Daniel, and that was a comfort. They had spent nights drinking and talking whenever Daniel was home, and it had settled something in his aching bones but that was gone now. Daniel missed it. He missed Steven, but as a hand slid into his, Daniel felt something settle down within him. Suddenly the streets didn't look that unfamiliar, and the faces weren't just a blurr anymore because Daniel wasn't stuck in place. No, as he looked at Lando who was smiling at him softly, Daniel was moving forward with his life. He was letting the chance to be happy, to be more than the shadows of his past, win. "Ready to show me around?", Lando grinned, fingers squeezing his softly, "I want to see where you grew up" For once, walking through these streets didn't seem daunting with Lando by his side. "Yeah, I am", Daniel smiled and leaned down to kiss Lando softly.

It felt like home.

#dando#daniel/lando#lando/daniel#more introspective than I meant#but have the dando#lando is daniel's home

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

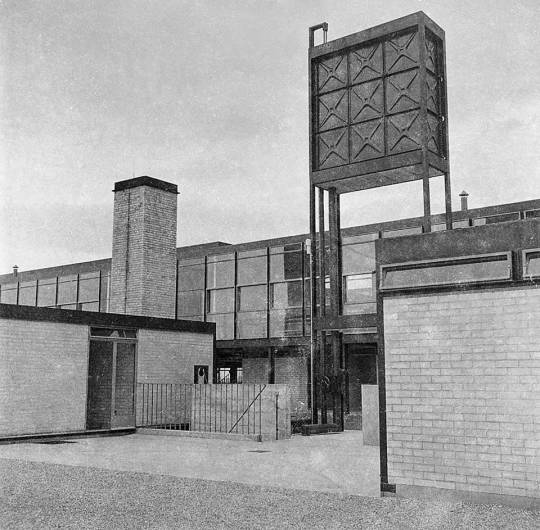

Hunstanton School Alison and Peter Smithson Norfolk, England, 1949

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nigel Henderson, Exterior of Hunstanton Secondary Modern School, Norfolk, during construction, c. 1953 x

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Hunstanton Fun Dog Show is taking place at the weekend with inflatable obstacle course

New Post has been published on https://petn.ws/Bk81i

The Hunstanton Fun Dog Show is taking place at the weekend with inflatable obstacle course

A dog show will provide fun for the whole family – and there will even be a giant inflatable obstacle course for youngsters. The Hunstanton Fun Dog Show, organised by The Barking Bugle, will be taking place this Saturday at Glebe House School on Cromer Road. There are 14 classes to enter, with rosettes up […]

See full article at https://petn.ws/Bk81i #DogNews

0 notes

Text

Will it Blend?

Brutalism Research

architectural style with an emphasis on materials, textures and construction, producing highly expressive forms.

First seen in work by Le Corbusier in the late 1940s with the Unité d'Habitation in Marseille

it was architectural historian, Reyner Banham’s review in 1955 of Alison and Peter Smithson’s school at Hunstanton in Norfolk, with its approach to the display of the steel and brick structure that established the movement.

Features of Brutalist architecture include - rough surfaces, massive forms, unusual shapes and expression of structure, lack of ornamentation, and monochromatic palette, and simple graphic lines

The style is both popular and unpopular

The style began to fade out in the 1980s when it became known as cold, alienating and unfit for humans

Concrete had an allure of indestructibility but deteriorated from the inside

Brutalist buildings tend to be now neglected and covered in graffiti

The love of brutalist architecture in the Soviet Union meant that the style began to be associated with totalitarianism

Research:

Architecture.com. (2023). Brutalism. [online] Available at: https://www.architecture.com/explore-architecture/brutalism#:~:text=Brutalism%20in%20architecture,construction%2C%20producing%20highly%20expressive%20forms. [Accessed 4 Oct. 2023].

The Spruce. (2020). What Is Brutalism? [online] Available at: https://www.thespruce.com/what-is-brutalism-4796578 [Accessed 4 Oct. 2023].

Photos:

Dam Tunnel In The Woods Outside Pittsfield, Massachusetts. (2023). [Online Image] Demilked. Available at: https://static.demilked.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/stunning-brutalist-architecture-19.jpg [Accessed 4 Oct. 2023].

Johnson, P. (1954). School at Hunstanton, Norfolk, by Alison and Peter Smithson. [Photograph] Architectural Review. Available at: https://www.architectural-review.com/buildings/school-at-hunstanton-norfolk-by-alison-and-peter-smithson [Accessed 4 Oct. 2023].

Kozlowski, P. (n.d.). Unité d’Habitation. [Photograph] Architectural Exhibitions International. Available at: https://www.architecture-exhibitions.com/sites/default/files/900x720_2049_791.jpg [Accessed 4 Oct. 2023].

0 notes

Text

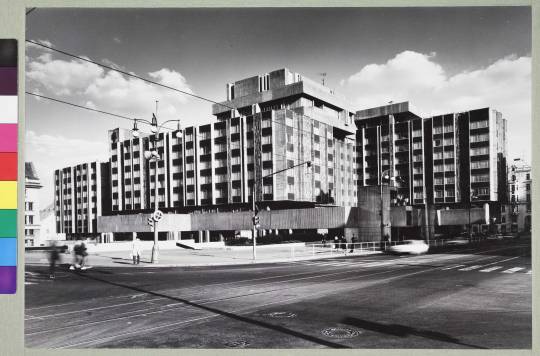

Brutalism

Brutalism is an architectural style that places emphasis textures, materials, construction, expression, practicality, and utilitarianism. The style is often characterised by its rough textures, hard edges, rigid geometric shapes, blocky appearances, lack of decoration, simple graphic lines, monochromatic colour palette, and an almost monolithic sense of presence. Scale was a large aspect of brutalist architecture. In addition, brutalism made use of unusual shapes that can easily be differentiated through the use of light and shadow (contrast). Brutalism is memorable and takes up space. Think of a skyscraper: its immense size, the way it takes up space in the open sky, and the way it forever alters your view of the skyline.

Common materials used in brutalist architecture include raw concrete (its most important stylistic motif), brick, glass, steel, and stone.

The term ‘Brutalism’ is derived from the phrase ‘Béton brut,’ which means raw concrete. Brutalist architecture can be observed as far back as the 1940s, with the first example being Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation in Marseilles, France.

The style emerged during the 20th century modernist movement, with the term first being coined in 1949 by Swedish architect Hans Asplun to describe the Villa Göth in Uppsala. The term was then popularised in 1955 when it was used by architectural historian Reyner Banham, when reviewing a school at Hunstanton, Norfolk.

The style grew in popularity through the 1950s and ‘60s, and became the favoured form of architecture for government buildings.

Brutalism as a philosophy focused on bringing modern, developed, almost utopian environments to life. This was a post-WWII era, where urban reconstruction was a pressing matter. Many of the European cities were damaged by bombs and the end of a World War meant a population boom for the US and Europe. This meant that architects needed to design large scale institutional buildings as well as high density affordable residential complexes. The 1950s and 60s was also a time of great technological and social development, creating this culture of optimism and hope for a better future. This zeitgeist was reflected in brutalism; with the movement focusing on functionality and community, and becoming synonymous with socially progressive housing plans that depicted the modern utopian buildings of the future.

Brutalism eventually fell out of style in the 1980s and ‘90s, when the architecture became associated with urban decay, crime, social depravity, economic hardship, and anti-environmentalism. This was partially due to the fact that the raw concrete did not age well, often being prone to decay and water damage. The style also began to be seen as cold, alienating, and lacking in humanity. In addition, due to the architecture being adopted by the Soviet Union, the style began to become associated with totalitarianism, dictatorship, and social control/conformity. This was the period of the Cold War, and therefore the height of the Red Scare, thus creating a widespread fear of communism in the west that Brutalism unfortunately suffered from.

The Brutalist Playground (2015)

Simon Terrill collaborated with Assemble to create a brutalist art installation that “recreated a trio of post-war play structures out of foam.” The installation was displayed at the Royal British Institute of British Architects gallery. The playground was inspired by the Churchill Gardens in Pimlico, the Brownfield Estate in Poplar, and the Brunel Estate in Paddington. Terrill recreated these structures using colourful foam.

Simon Terrill

Simon Terrill is an Australian artist based in London who is preoccupied by the relationship between architecture and the narratives and stories we construct around these spaces. He explores how spaces are constructed and informed by the people that inhabit it.

This greatly relates to our study of heterotopias, as a primary characteristic of heterotopias is how it is constructed as a closed off space for specific social functions, and how it changes over time as society changes around it.

0 notes

Text

The Old Barn + Churnery, Norfolk Coastal Cottages

This self-catering vacation cottage is located on the lovely North Norfolk Coast, just a short walk from the large sandy unspoilt beach. The property is located on the corner of Quayside and is an excellent starting point for exploring the region. The house has its own enclosed yard, where the kitchen, utility room, and pantry are located.

This 12th century Norfolk cottage is open all year and greets guests with open arms. In the heart of Norfolk, there is a hidden gem.

Bring your dog with you to the beach instead of leaving it at home. Our family cottages are offered for exclusive self-catering rentals, making them an ideal location for dog-friendly beach vacations. With 6 bedrooms and a huge kitchen, it's ideal for larger groups, but it's also enjoyable for families of four or two couples, as long as you and your closest friends are seeking for luxurious coastal comfort.

COTTAGES BY THE SEA IN NORFOLK

Our Norfolk Coastal Cottages provide a unique and charming respite from the rush and bustle of city life. Our isolated, tranquil rental cottages feature beautiful views of Norfork's pristine coastline and are only a short walk away from several stunning attractions, including miles of untouched shoreline. Our charming North Norfolk Beach cottages are the perfect backdrop for a romantic break or a family holiday. It has stunning landscapes, wonderful beaches, and a variety of activities for everyone to enjoy.

The North Norfolk Coastline has been designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, and it is one of only two regions in the county that are legally protected from development. This means that there are few houses or structures in this area, allowing you to fully experience the natural beauty all around you.

There are several ways to enjoy your stay at our North Norfolk Beach cottages at Norfolk Coast B&B Cottages and Camping. You can walk down the beach, relax on one of our numerous patios or balconies with beautiful views, go fishing, or simply spend time exploring the surrounding area on foot or horseback! Other outdoor activities accessible include golfing, biking, horseback riding, and water sports such as sailing and windsurfing! You will never be bored while staying at our private rental cottages because there is so much to see and do!

HISTORY: FOR CENTURIES, THE NORFOLK COAST HAS BEEN A POPULAR VACATION DESTINATION.

The North Norfolk Coast has long been a favorite vacation destination, but with so many wonderful sites to visit, picking just one can be difficult. We've compiled a list of our top five tucked-away jewels on the North Norfolk Coast that you won't want to miss when planning your trip to this beautiful corner of the world.

The coastline, which spans for more than 100 miles, is home to charming villages, beautiful beaches, and historic sites. Hiking, motorcycling, fishing, and bird watching are among the activities available to visitors. The Norfolk Coast is also famed for its delectable seafood eateries, such as The White Horse in Brancaster Staithe and The Kings Head in Blakeney.

The Norfolk Coast was named one of the greatest locations to live in the UK by The Sunday Times in 2019. The annual Finest Places to Live guide published by the newspaper assists readers in determining the best places to buy a home and live in Britain. It considers criteria such as quality of life, jobs, schools, community spirit, and local facilities. The "unspoiled shoreline," "quaint villages," and "really lovely scenery" of the Norfolk Coast were all lauded.

WINTERTON-ON-SEA

Winterton is well-known for being Norfolk's only seaside resort with direct access to the North Sea and its own beach. Since Victorian times, this county town has been a popular vacation destination, and it offers plenty of possibilities for walking over scenic beach dunes, exploring tiny shops, and simply relaxing by the ocean with a good book or coffee and friends.

HUNSTANTON

Hunstanton, like Winterton, has long functioned as a gathering place over the centuries. In fact, great author Geoffrey Chaucer included Hunstanton in his epic work "The Canterbury Tales" about 700 years ago! Today, visitors come for the endless beaches flanked by rock cliffs, or for the rich history at landmarks such as Old Hunstanton Chapel and The Red Mount Chapel, which were erected in 1585 from flintstone uncovered during building at nearby Holme-next-the-Sea.

SHERINGHAM

Sheringham is about 10 miles north of Cromer and is known for its fishing heritage, sandy beaches surrounded by rocky cliffs, and charming stone architecture such as All Saints Church, which was built in 1421 on Beeston Bump hilltop and offers beautiful views of both land and sea vistas below!

WELL-NEXT-THE-SEA

None of the seaside towns on the Norfolk Coast compare to charming unhurried Wells, where colorful beach cottages line a large golden sands beach stretching from the renowned striped red and white Holkham Hall inlets to the Stiffkey salt marshes. Take a leisurely boat ride through The Nature Reserve for a closer look at local seal populations or participate in the mussel-picking tradition as an added treat!

THE HOLKHAM HALL

Finally, we arrive at one of Norfolk's best-kept secrets: the magnificent Holkham Hall. This stunning Palladian mansion was built between 1734-1764 on 25,000 acres of pristine parkland and deer herds and is still home to the Earl of Leicester's family today who welcome visitors from near and far year-round to share in its beauty whether it be exploring the house itself or enjoying outdoor activities like horse riding, cycling, or simply taking a peaceful stroll around Holkham Estate's lake villages dotted with thatched cottages!

The coastline, which spans for more than 100 miles, is home to charming villages, beautiful beaches, and historic sites. Hiking, motorcycling, fishing, and bird watching are among the activities available to visitors. The Norfolk Coast is also famed for its delectable seafood eateries, such as The White Horse in Brancaster Staithe and The Kings Head in Blakeney.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Alison y Peter Smithson. Hunstanton Secondary School (Norfolk, 1949-54)

143 notes

·

View notes

Photo

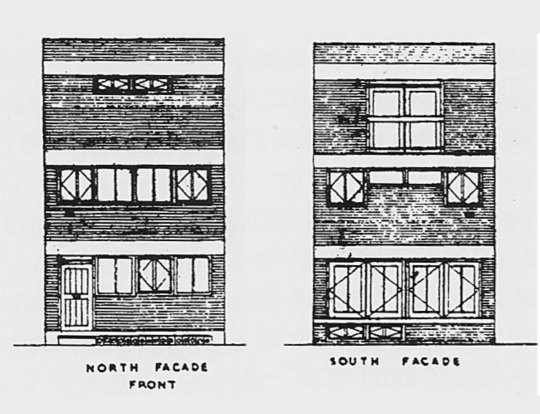

Smithdon School Hunstanton, Norfolk, East of England, UK; 1949-54

Alison and Peter Smithson

see map | more information 1, 2, 3, 4 | pictures

via "Bauen + Wohnen" 13 (1959)

#architecture#arquitectura#architektur#architettura#smithdon#smithdon school#school#schule#escola#alison smithson#peter smithson#alison peter smithson#hunstanton#norfolk#east of england#england#united kingdom#uk#british architecture

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Brutalism Post Part 3: What is Brutalism? Act 1, Scene 1: The Young Smithsons

What is Brutalism? To put it concisely, Brutalism was a substyle of modernist architecture that originated in Europe during the 1950s and declined by the 1970s, known for its extensive use of reinforced concrete. Because this, of course, is an unsatisfying answer, I am going to instead tell you a story about two young people, sandwiched between two soon-to-be warring generations in architecture, who were simultaneously deeply precocious and unlucky.

It seems that in 20th century architecture there was always a power couple. American mid-century modernism had Charles and Ray Eames. Postmodernism had Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown. Brutalism had Alison and Peter Smithson, henceforth referred to simply as the Smithsons.

If you read any of the accounts of the Smithsons’ contemporaries (such as The New Brutalism by critic-historian Reyner Banham) one characteristic of the pair is constantly reiterated: at the time of their rise to fame in British and international architecture circles, the Smithsons were young. In fact, in the early 1950s, both had only recently completed architecture school at Durham University. Alison, who was five years younger, was graduating around the same time as Peter, whose studies were interrupted by the Second World War, during which he served as an engineer in India.

Alison and Peter Smithson. Image via Open.edu

At the time of the Smithsons graduation, they were leaving architecture school at a time when the upheaval the war caused in British society could still be deeply felt. Air raids had destroyed hundreds of thousands of units of housing, cultural sites and had traumatized a generation of Britons. Faced with an end to wartime international trade pacts, Britain’s financial situation was dire, and austerity prevailed in the 1940s despite the expansion of the social safety net. It was an uncertain time to be coming up in the arts, pinned at the same time between a war-torn Europe and the prosperous horizon of the 1950s.

Alison and Peter married in 1949, shortly after graduation, and, like many newly trained architects of the time, went to work for the British government, in the Smithsons’ case, the London City Council. The LCC was, in the wake of the social democratic reforms (such as the National Health Service) and Keynesian economic policies of a strong Labour government, enjoying an expanded range in power. Of particular interest to the Smithsons were the areas of city planning and council housing, two subjects that would become central to their careers.

Alison and Peter Smithson, elevations for their Soho House (described as “a house for a society that had nothing”, 1953). Image via socks-studio.

The State of British Architecture

The Smithsons, architecturally, ideologically, and aesthetically, were at the mercy of a rift in modernist architecture, the development of which was significantly disrupted by the war. The war had displaced many of its great masters, including luminaries such as the founders of the Bauhaus: Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Marcel Breuer. Britain, which was one of the slowest to adopt modernism, did not benefit as much from this diaspora as the US.

At the time of the Smithsons entry into the architectural bureaucracy, the country owed more of its architectural underpinnings to the British architects of the nineteenth century (notably the utopian socialist William Morris), precedent studies of the influences of classical architecture (especially Palladio) under the auspices of historians like Nikolaus Pevsner, as well as a preoccupation with both British and Scandinavian vernacular architecture, in a populist bent underpinned by a turn towards social democracy. This style of architecture was known as the New Humanism.

Alton East Houses by the London County Council Department of Architecture (1953-6), an example of New Humanist architecture. Image taken from The New Brutalism by Reyner Banham.

This was somewhat of a sticky situation, for the young Smithsons who, through their more recent schooling, were, unlike their elders, awed by the buildings and writing of the European modernists. The dramatic ideas for the transformation of cities as laid out by the manifestos of the CIAM (International Congresses for Modern Architecture) organized by Le Corbusier (whose book Towards a New Architecture was hugely influential at the time) and the historian-theorist Sigfried Giedion, offered visions of social transformation that allured many British architects, but especially the impassioned and idealistic Smithsons.

Of particular contribution to the legacy of the development of Brutalism was Le Corbusier, who, by the 1950s was entering the late period of his career which characterized by his use of raw concrete (in his words, béton brut), and sculptural architectural forms. The building du jour for young architects (such as Peter and Alison) was the Unité d’Habitation (1948-54), the sprawling massive housing project in Marseilles, France, that united Le Corbusier’s urban theories of dense, centralized living, his architectural dogma as laid out in Towards a New Architecture, and the embrace of the rawness and coarseness of concrete as a material, accentuated by the impression of the wooden board used to shape it into Corb’s looming, sweeping forms.

The Unité d’habitation by Le Corbusier. Image via Iantomferry (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Little did the Smithsons know that they, mere post-graduates, would have an immensely disruptive impact on the institutions they at this time so deeply admired. For now, the couple was on the eve of their first big break, their ticket out of the nation’s bureaucracy and into the limelight.

The Hunstanton School

An important post-war program, the one that gave the Smithsons their international debut, was the expansion of the British school system in 1944, particularly the establishment of the tripartite school system, which split students older than 11 into grammar schools (high schools) and secondary modern schools (technical schools). This, inevitably, stimulated a swath of school building throughout the country. There were several national competitions for architects wanting to design the new schools, and the Smithsons, eager to get their hands on a first project, gleefully applied.

For their inspiration, the Smithsons turned to Mies van der Rohe, who had recently emigrated to the United States and release to the architectural press, details of his now-famous Crown Hall of the Illinois Institute of Technology (1950). Mies’ use of steel, once relegated to being hidden as an internal structural material, could, thanks to laxness in the fire code in the state of Illinois, be exposed, transforming into an articulated, external structural material.

Crown Hall, Illinois Institute of Technology by Mies van der Rohe. Image via Arturo Duarte Jr. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Of particular importance was the famous “Mies Corner,” consisting of two joined exposed I-beams that elegantly elided inherent problems in how to join together the raw, skeletal framing of steel and the revealing translucence of curtain-wall glass. This building, seen only through photographs by our young architects, opened up within them the possibility of both the modernist expression of a structure’s inherent function, but also as testimony to the aesthetic power of raw building materials as surfaces as well as structure.

The Smithsons, in a rather bold move for such young architects, decided to enter into a particularly contested competition for a new secondary school in Norfolk. They designed a school based on a Miesian steel-framed design of which the structural elements would all be visible. Its plan was crafted to the utmost standards of rationalist economy; its form, unlike the horizontal endlessness of Mies’ IIT, is neatly packaged into separate volumes arranged in a symmetrical way. But what was most important was the use of materials, the rawness of which is captured in the words of Reyner Banham:

“Wherever one stands within the school one sees its actual structural materials exposed, without plaster and frequently without paint. The electrical conduits, pipe-runs, and other services are exposed with equal frankness. This, indeed, is an attempt to make architecture out of the relationships of brute materials, but it is done with the very greatest self-denying restraint.”

Much to the upset and shock of the more conservative and romanticist British architectural establishment, the Smithsons’ design won.

Hunstanton School by Alison and Peter Smithson (1949-54). Photos by Anna Armstrong. (CC BY NC-SA 3.0)

The Hunstanton School, had, as much was possible in those days, gone viral in the architectural press, and very quickly catapulted the Smithsons to international fame as the precocious children of post-war Britain. Soon after, the term the Smithsons would claim as their own, Brutalism, too entered the general architectural consciousness. (By the early 1950s, the term was already escaping from its national borders and being applied to similar projects and work that emphasized raw materials and structural expression.)

The New Brutalism

So what was this New Brutalism?

The Smithsons had, even before the construction of the Hunstanton School had been finished, begun to draft amongst themselves a concept called the New Brutalism. Like many terms in art, “Brutalism” began as a joke that soon became very serious. The term New Brutalism, according to Banham, came from an in-joke amongst the Swedish architects Hans Asplund, Bengt Edman and Lennart Holm in 1950s, about drawings the latter two had drawn for a house. This had spread to England through the Swedes’ English friends, the architects Oliver Cox and Graeme Shankland, who leaked it to the Architectural Association and the Architect’s Department of the London County Council, at which Alison and Peter Smithson were still employed. According to Banham, the term had already acquired a colloquial meaning:

“Whatever Asplund meant by it, the Cox-Shankland connection seem to have used it almost exclusively to mean Modern Architecture of the more pure forms then current, especially the work of Mies van der Rohe. The most obstinate protagonists of that type of architecture at the time in London were Alison and Peter Smithson, designers of the Miesian school at Hunstanton, which is generally taken to be the first Brutalist building.”

(This is supplicated by an anecdote of how the term stuck partially because Peter was called Brutus by his peers because he bore resemblance to Roman busts of the hero, and Brutalism was a joining of “Brutus plus Alison,” which is deeply cute.)

The Smithsons began to explore the art world for corollaries to their raw, material-driven architecture. They found kindred souls in the photographer Nigel Henderson and the sculptor Edouardo Paolozzi, with whom the couple curated an exhibition called “Parallel of Life and Art.” The Smithsons were beginning to find in their work a sort of populism, regarding the untamed, almost anthropological rough textures and assemblies of materials, which the historian Kenneth Frampton jokingly called ‘the peoples’ detailing.’ Frampton described the exhibit, of which few photographs remain, as thus:

“Drawn from news photos and arcane archaeological, anthropological, and zoological sources, many of these images [quoting Banham] ‘offered scenes of violence and distorted or anti-aesthetic views of the human figure, and all had a coarse grainy texture which was clearly regarded by the collaborators as one of their main virtues’. There was something decidedly existential about an exhibition that insisted on viewing the world as a landscape laid waste by war, decay, and disease – beneath whose ashen layers one could still find traces of life, albeing microscopic, pulsating within the ruins…the distant past and the immediate future fused into one. Thus the pavilion patio was furnished not only with an old wheel and a toy aeroplane but also with a television set. In brief, within a decayed and ravaged (i.e. bombed out) urban fabric, the ‘affluence’ of a mobile consumerism was already being envisaged, and moreover welcomed, as the life substance of a new industrial vernacular.”

Alison and Peter Smithson, Nigel Henderson, Eduoardo Paolozzi, Parallels in Life and Art. Image via the Tate Modern, 2011.

A Clash on the Horizon

The Smithsons, it is important to remember, were part of a generation both haunted by war and tantalized by the car and consumer culture of the emerging 1950s. Ideologically they were sandwiched between the twilight years of British socialism and the allure of a consumerist populism informed by fast cars and good living, and this made their work and their ideology rife with contradiction and tension.

The tension between proletarian, primitivist, anthropological elements as expressed in coarse, raw, materials and the allure of the technological utopia dreamed up by modernists a generation earlier, combined with the changing political climate of post-war Britain, resulted in a mix of idealism and post-socialist thought. This hybridized an new school appeal to a better life - made possible by technology, the emerging financial accessibility of consumer culture, the promises of easily replicable, luxurious living promised by modernist architecture - with the old-school, quintessentially British populist consideration for the anthropological complexity of urban, working class life. This is what the Smithsons alluded to when they insisted early on that Brutalism was an “ethic, not an aesthetic.”

Model of the Plan Voisin for Paris by Le Corbusier displayed at the Nouveau Esprit Pavilion (1925) via Wikipedia (CC BY-SA 4.0)

By the time the Smithsons entered the international architectural scene, their modernist forefathers were already beginning to age, becoming more stylistically flexible, nuanced, and less reliant upon the strictness and ideology of their previous dogmas. The younger generation, including the Smithsons, were, in their rose-tinted idealism, beginning to feel like the old masters were abandoning their original ethos, or, in the case of other youngsters such as the Dutch architect Aldo van Eyck, were beginning to question the validity of such concepts as the Plan Voisin, Le Corbusier’s urbanist doctrine of dense housing development surrounded by green space and accessible by the alluring future of car culture.

These youngsters were beginning to get to know each other, meeting amongst themselves at the CIAM – the International Congresses of Modern Architecture – the most important gathering of modernist architects in the world. Modern architecture as a movement was on a generational crash course that would cause an immense rift in architectural thought, practice, and history. But this is a tale for our next installment.

Like many works and ideas of young people, the nascent New Brutalism was ill-formed; still feeling for its niche beyond a mere aesthetic dominated by the honesty of building materials and a populism trying to reconcile consumerist technology and proletarian anthropology. This is where we leave our young Smithsons: riding the wave of success of their first project as a new firm, completely unaware of what is to come: the rift their New Brutalism would tear through the architectural discourse both then and now.

If you like this post, and want to see more like it, consider supporting me on Patreon!

There is a whole new slate of Patreon rewards, including: good house of the month, an exclusive Discord server, monthly livestreams, a reading group, free merch at certain tiers and more!

Not into recurring donations or bonus content? Consider the tip jar! Or, Check out the McMansion Hell Store! Proceeds from the store help protect great buildings from the wrecking ball.

#brutalism#architecture#architectural history#brutalism post#smithsons#alison and peter smithson#british architecture#modern architecture#le corbusier#concrete#brutalist architecture

933 notes

·

View notes

Text

Demolitions

for Czechoslovakia’s architectures between 1960s–1980s is a controversial subject. The public may still regard it negatively, owing to a lack of information or an adverse experience with the country’s regime before the Velvet Revolution.

Omnipol Building by Zdeněk Kuna, Zdeněk Stupka, Milan Valenta, Josef Zdražil, Ladislav Vrátník (1974–1979) | Photo © Kamil Warta, National Gallery Prague

youtube

Erosion of Transgas (2020) by NGP/Loom on the Moon

Helena Doudová, the curator of the exhibition NO DEMOLITIONS! Forms of Brutalism in Prague, presents Brutalism buildings in Prague that prominently enter the urban scene. The nearly two hundred and fifty original architectural plans, photographs and models come mostly from the Architecture Collection of the National Gallery Prague. The examples of the most progressive architecture works feature the Kotva Department Store, the former Central Telecommunications Building at Žižkov (marked for demolition), the former Federal Assembly, Hotel Intercontinental and Barrandov Bridge and the recently demolished Transgas complex.

“No Demolitions!” is a quite straightforward title for an exhibition. What is happening in Prague and the Czech Republic, that led you to organize this exhibition and choose this title?

With the exhibition we intended to highlight the values of late modern and brutalist architecture in Prague that becomes either demolished or refurbished beyond the point of recognition. Some of the buildings ceased to exist throughout the one year since we started working on the topic. We intended to show that the buildings by the architects like Karel Prager, Karel Filsak, the husband-and-wife team Machoninovi and Šrámkovi have built edifices, which are comparable with the most prestigious architecture production of the former Western Europe and the US.

Center of Home Design by Věra Machoninová, Vladimír Machonin (1971–1981) | | Photo © Kamil Wartha, National Gallery Prague

The Trade Fair Palace is an exclusive choice for an architectural exhibition; why did you choose this location?

It is a building with strong symbolic meaning, a real jewel of functionalist architecture but at the same time it is difficult to present an exhibition due to technical parameters as light because paper plans and photography are very sensitive to it. The gallery floor plan worked quite well in a sequence, so the exhibition concept fit quite well. Ondřej Císler created vitrines with colored large plans and prints from the architecture collection of the National Gallery in Prague. Plans are contrasted with the photography of the deteriorated state of the buildings by Olja Triaška Stefanović.

In many countries of the former East Bloc, protecting Late Modern architecture creates a specific challenge, as these buildings are widely associated with the negative perception of the political era they were created in. This can very easily lead to iconoclastic gestures, as we have seen in the case of Skopje 2014. What can art history, museology and the wider profession do against this phenomenon?

The negative public opinion toward these buildings is a cluster of multiple problems. One general problem not only in the Central or Eastern Europe is the poor long term maintenance, which makes the buildings appear even more brutal than intended in the architecture design. As the exhibition shows, the architects were thinking of the public space around these buildings, inserted artworks and parks, as a number of designs show.

Secondly, the political associations are difficult, but also controversial to me. I very much think that the socialist state invested into large public buildings before 1989 and did provide socially accessible culture programs, sports, etc. So to me the brutalist buildings are valuable and authentic through their aim to belong to the community but also undercover propaganda. One can’t change people's memories or their experience with communism, but it’s not the fault of buildings that were ironically planned in the golden sixties in the time of the political détente in Czechoslovakia.

The exhibition | Photo © Katarína Hudačinová, the National Gallery Prague

In comparison, no large public building in Prague has been built since 30 years, what shows the shift of the capital flow with privatization. Nowadays, the real estate investors misuse the negative public opinion to demolish high quality buildings to acquire lucrative plots in the city centre for private investment. In many cases it would have been possible to reuse the brutalist buildings at a lower expense, like for example the Embassy of CZ in Berlin.

The National Gallery seems to be a prestigious place for the exhibition about the architecture of an era that is widely disputed and is also a strong institutional statement; how are Czech academics and professionals reacting to the events around the architecture of the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s?

I very much believe in the power of the exhibition as a tool for mediation and education, but also bringing up controversial or uncomfortable topics. That is the position the National Gallery has. Its architecture collection is centred around post-1945 architecture so it is logical to present it in an innovative perspective. Brutalism has received international acclaim in architecture history since 2010s, so we have had many academic discussions, but to me it is important to bring the phenomenon to the public. It is interesting that the expression is the same in former East and West, the only difference is that in the former West the buildings like the MET Breuer are celebrated, while in the former East these buildings are admired by the professionals and despised by the wide public.

In most of our countries we see the profession and the public speaking out to protect some of these buildings, in Hungary this happened by the proposed demolition of Zoltán Gulyás’ Chemolimpx office building in the early 2010s, and more recently when the government announced the demolition of Csaba Virág’s soc-hi-tech Electric Power Distribution Center. There are similar stories in Czechia and Poland - how do you explain the public being so involved in these cases?

Yes, there is an entire movement of active architecture historians, architects and interested public. David Crowley, the head of arts department of the NCAD in Dublin, is a great observer of these shifts, which demonstrate a renewal of the consciousness for public sphere and public spaces in general. So far the protests have been unsuccessful in confrontation with the investment pressures, a culmination point was the demolition of the Transgas building, public protests accompanied the demolition of Hotel Praha, and eventually rescued railway station in Havířov. Crowley says this a unique trait in Central Europe as he has not seen such engagement in the UK or Ireland. In Germany, the heritage protection of post-war buildings is really advanced by now, but there are not such strong public initiatives to me...

Transgas Complex by Ivo Loos, Jindřich Malátek, Václav Aulický, Jiří Eisenreich, Jiří Kozák, Jan Fišer (1966–1978) | Photo © Kamil Wartha, National Gallery Prague

Why did you choose brutalism as a specific style to sum up these buildings? Strictly speaking, the term is quite well defined and confined to a specific group of mostly British and American buildings, what is brutalism in your definition?

The usual association is béton brut, with the main inspiration of Le Corbusier. At the same time, I took at hand Rayner Banham, who speaks about three criteria, in short – the figure, the revealed construction and authenticity of material, which would better comply with the notion of brutalism in variety. Also brutalism has been changing from the expression of the Smithson's Hunstanton school, to let's say Paul Rudolph. In such way brutalism became an international expression with multiple specifics.

Hotel Intercontinental by Karel Filsak, Karel Bubeníček, Jiří Louda, Jaroslav Švec a kol. (1968–1974) | Photo © Kamil Wartha, National Gallery Prague

The notion of brutalism has been a subject of a dispute in the curatorial team with Petr Vorlík, Klára Brůhová (CTU Prague) and Radomíra Sedláková (NG Prague). We assumed the Czech architecture was influenced by brutalism, to a smaller or larger extent depending on every architect. Architecture of late modernism in Czech shows finer handling of material such as glass, mosaics, of wooden cladding, a variety of bright colours, that do not particularly express the notion of brutalism associated with rough concrete. The houses do in a way respect the scale of the surrounding city, are most often broken down in a composition of smaller volumes, reference bay windows of surrounding houses, etc.

PZO Centrotex Building – Václav Hilský, Otakar Jurenka (1972–1978) | Photo © Kamil Wartha, National Gallery Prague

At the same time the label brutalism is in public drawn to all kinds of buildings, which have with little or nothing to do with late modernism, actually, are clad in stone. So as architecture historians we strived to differentiate and raise public awareness on the topic.

Is there a specific Czech brutalism? Are there any national or regional characteristics in this era?

This is not an easy question. Brutalism was a global and a local phenomenon. Interestingly, in the Czechoslovak architecture we see magazines that iconic brutalist buildings were published, like La Tourette, or the architecture by Stirling in the 1960s and 1970s. So the information iron curtain was more semi-penetrable in terms of architecture knowledge and expression, like Ákos Moravánszky says. The regional specifics construction processes, the quality and variability of materials, which was lower in the former Eastern block, and also the public opinion which incorrectly associates the buildings with state socialism.

We are talking about the architectural production of an era that produced an incredible amount of buildings. How is it possible to create a canon for such a recent past and what do you think about the monumental protection regarding these buildings? What should be protected and how? Can you also name a few example, interesting buildings (and interiors) from Czechia?

A unique example is the already heritage protected Kotva Department Store by architect's team Věra and Vladimír Machoninovi.

Kotva department store in Prague. | Photo © Olja Triaška Stefanović

The former Federal Assembly is another iconic example of a daring construction originally intended for bridges. It encloses the former classical modernist stock exchange building and complements the ensemble anew. Interiors have unfortunately been refurbished and only very few items are present in the museums.

Former Federal Assembly Building Prague. | Photo © Olja Triaška Stefanović

A unique example is the Czech embassy in Berlin with intact interiors. A contested interior reconstruction is currently Hotel Thermal by Machoninovi in Karlovy Vary. At least five outstanding buildings have been demolished in Prague, countless have been refurbished. Only two above-named brutalist buildings are heritage protected, other like Hotel Intercontinental by Filsak, or Centrotex by Hiský, Motokov by Kuna should become protected as unique works of art and architecture.

___

Interview by Dániel Kovács and first published in Epiteszforum.

Photo © Jan Faukner

Helena Doudová is curator of the Architecture Collection of the National Gallery Prague. She gained curatorial and museum experience as research and curatorial fellow of the International Museum Program in the German Museum of Books and Writing in Leipzig in collaboration with the University of Erfurt and the German Federal Cultural Foundation 2016/2017, as a Robert Bosch Fellow at Architecture Museum of the TU Munich – Pinakothek der Moderne (2011–2012) and as an intern in the German Architecture Centre DAZ in Berlin (2013–2014). She initiated and curated NO DEMOLITIONS! Forms of Brutalism in Prague, Baugruppe ist super!, Image Factories: Infographics 1920-1945: Fritz Kahn, Otto Neurath. She is a PhD candidate at the Institute of Art History of the University of Zurich. She was awarded DAAD research scholarship and Aktion Österreich scholarship.

***

NO DEMOLITIONS! Forms of Brutalism in Prague

From 6.3.2020 to 22.11.2020 at the Trade Fair Palace – 3rd floor Dukelských hrdinů 47, 170 00 Praha 7 Map

Curator: Helena Doudová Collaborating experts / co-curators: Klára Brůhová (FA CTU in Prague), Radomíra Sedláková (NGP), Petr Vorlík (FA CTU in Prague)

71 notes

·

View notes

Quote

It was very quiet. The woods were made for secrecy. They did not recognize her as the garden did. They did not care that for a whole year she could be at school, or at Hunstanton, or in London. The woods would never miss her: they had their own dark, passionate life.

“The Pool” in The��Blue Lenses and Other Stories, by Daphne du Maurier

1 note

·

View note

Note

I want to design a brutalist building, how do I imitate this style?

I don’t know what style you have in mind exactly. Maybe you’re thinking about the giant concrete structures we all love, but I’d advise to start with the roots and go from there.

Reyner Banham defined New Brutalism as follows:

1, Formal legibility of a plan; 2, Clear exhibition of Structure; and 3, Valuation of Materials ‘as found.’

You could study the use of materials in two of the early works by Alison and Peter Smithson:

Hunstanton School, Norfolk, 1949-54

Sugden House, Watford, 1955

95 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Economist Buildings, St. James Street, Westminster (1964) by Alison & Peter Smithson.

The Economist buildings on St. James Street, Westminster opened on December 10th 1964. The buildings were designed by Alison and Peter Smithson, who had brought brutalism to Britain with their school in Hunstanton, Norfolk in 1954. Here the Smithsons replaced an older set of buildings with three towers of varying height on a raised plaza, a piece of Chicago transplanted to higgledy piggledy Central London.

The buildings are constructed around concrete frames with Portland sandstone facades and metal windows. The plaza featured work by Eduardo Paolozzi, and is itself formed of slabs of Portland stone. The scheme is now Grade II* listed and undergoing refurbishment by DSDHA.

Images from Art & Architecture and DSDHA

Modernist London

22 notes

·

View notes