#Hunan culinary heritage

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Exploring the Flavorful World of Hunan Cuisine: Traditional Chinese Food and Language Translation

Uncovering the Culinary Heritage of Hunan The landlocked province of Hunan in central China is a treasury of cultural riches waiting to be explored. At its heart lies a tapestry of culinary traditions interwoven with the language, history, and lifestyles of its people. This article invites you to embark on a journey through the authentic flavors and narratives that have shaped Hunan’s vibrant…

View On WordPress

#Chinese cooking techniques#Hunan cuisine#Hunan culinary heritage#Hunan culture#Hunan dialect#Hunan food traditions#Language Services#LanguageXS#Remote Interpreting#Xiang Chinese

0 notes

Text

The Eight Culinary Traditions of China: A Journey Through Unique Flavors

China’s culinary landscape is a tapestry woven from diverse regional flavors, cooking techniques, and cultural influences. The eight culinary traditions—Cantonese, Sichuan, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Hunan, Anhui, and Shandong—offer a glimpse into the nation’s rich gastronomic heritage. This article delves into each of these traditions, highlighting their distinctive characteristics, signature…

0 notes

Text

U.S. Ethnic Food Market Forecast and Analysis Report (2023-2032)

The U.S. ethnic food market is projected to grow from USD 24,759.29 million in 2023 to an estimated USD 46,729.84 million by 2032, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7.22% from 2024 to 2032.

The U.S. ethnic food market is experiencing substantial growth, driven by the country's increasing cultural diversity and the rising consumer interest in exploring global cuisines. This market encompasses a wide range of products, including Asian, Latin American, Middle Eastern, and African foods, each bringing unique flavors and culinary traditions to American consumers. Factors such as globalization, travel, and the influence of immigrant communities have significantly contributed to the popularity of ethnic foods. Additionally, the younger generation's adventurous palate and the growing demand for authentic, high-quality, and diverse food options are fueling this trend. Supermarkets, specialty stores, and online platforms are expanding their ethnic food offerings to meet this demand, with many mainstream food manufacturers also entering the market. The rise of ethnic food festivals, cooking shows, and food blogs further promotes awareness and appreciation of these cuisines. Overall, the U.S. ethnic food market is poised for continued expansion, reflecting broader trends towards culinary inclusivity and global interconnectedness.

Ethnic food refers to cuisine that originates from the culinary traditions of a particular ethnic group, culture, or region, often distinct from the mainstream food culture of the area where it is consumed. These foods are typically characterized by unique flavors, ingredients, cooking techniques, and recipes that are specific to a particular cultural or geographical background. Ethnic foods offer a taste of the culinary heritage of different communities and are often associated with the following characteristics:

Distinctive Ingredients: Ethnic foods use specific ingredients that are often native to or commonly used in the region of origin. These can include unique spices, herbs, fruits, vegetables, grains, and proteins.

Traditional Recipes: The preparation methods and recipes for ethnic foods are often passed down through generations, preserving the authenticity and cultural significance of the cuisine.

Cultural Significance: Ethnic foods are often deeply rooted in the culture and traditions of a community. They can be associated with cultural practices, religious rituals, festivals, and celebrations.

Variety and Diversity: Ethnic foods encompass a wide range of dishes, from appetizers and main courses to desserts and beverages. Each ethnic cuisine offers a diverse array of flavors and culinary experiences.

Regional Variations: Within a broader ethnic category, there can be significant regional variations. For example, Chinese cuisine includes distinct regional styles such as Cantonese, Sichuan, and Hunan.

Examples of ethnic foods include:

Asian Cuisine: Sushi, dim sum, pad Thai, pho, kimchi, and curry.

Latin American Cuisine: Tacos, empanadas, feijoada, tamales, and ceviche.

Middle Eastern Cuisine: Falafel, hummus, shawarma, kebabs, and baklava.

African Cuisine: Jollof rice, injera, tagine, and biltong.

European Cuisine: Paella, pasta, bratwurst, and moussaka.

Key players:

Conagra Brands, Inc.

General Mills, Inc.

PepsiCo, Inc.

McCormick & Company, Incorporated

Ajinomoto Co., Inc.

Kraft-Heinz Company

Frontera Foods (Conagra Brands)

Unilever Group

Mars, Incorporated

Hormel Foods Corporation

Thai Union Group Public Company Limited

MTR Foods

B&G Foods

More About Report- https://www.credenceresearch.com/report/us-ethnic-food-market

The dynamics of the U.S. ethnic food market are shaped by various factors, reflecting the diverse and evolving food preferences of American consumers. Key dynamics include:

1. Cultural Diversity:

The increasing cultural diversity in the United States, driven by immigration and the presence of various ethnic communities, plays a significant role in the demand for ethnic foods. Immigrants bring their culinary traditions with them, and their influence spreads to the broader population.

2. Consumer Interest in Global Cuisines:

American consumers, especially younger generations, are increasingly adventurous and open to trying new and exotic foods. This curiosity drives the demand for ethnic foods, as people seek authentic and diverse culinary experiences.

3. Health and Wellness Trends:

Many ethnic foods are perceived as healthier options, featuring fresh ingredients, balanced meals, and unique flavor profiles that align with health and wellness trends. Consumers seeking healthier diets often turn to ethnic cuisines that emphasize vegetables, lean proteins, and whole grains.

4. Availability and Accessibility:

The availability of ethnic foods in mainstream grocery stores, specialty markets, and online platforms has increased significantly. Retailers are expanding their ethnic food sections, and e-commerce platforms are making it easier for consumers to access a wide range of international products.

5. Influence of Media and Pop Culture:

Television shows, cooking channels, food blogs, and social media platforms play a crucial role in popularizing ethnic foods. Celebrity chefs and food influencers often showcase ethnic recipes and dining experiences, sparking interest and encouraging consumers to explore new cuisines.

6. Innovation and Fusion Cuisine:

Innovation in food production and culinary techniques has led to the creation of fusion cuisine, blending elements of different ethnic foods to create unique dishes. This trend appeals to consumers looking for novel and exciting flavors.

7. Economic Factors:

Economic factors, such as disposable income and spending power, influence the consumption of ethnic foods. As consumers' purchasing power increases, they are more likely to spend on diverse and premium food options, including ethnic cuisines.

8. Restaurant and Food Service Industry:

The growth of ethnic restaurants and food trucks across the U.S. provides consumers with more opportunities to experience authentic ethnic foods. The food service industry continues to expand its offerings to meet the growing demand for ethnic dining experiences.

9. Marketing and Branding:

Effective marketing and branding strategies are essential for ethnic food products. Brands that emphasize authenticity, quality, and cultural heritage can attract a loyal customer base. Additionally, collaborations with ethnic chefs and influencers can enhance brand credibility and visibility.

10. Regulatory and Supply Chain Considerations:

Ensuring the availability of authentic ingredients can be challenging due to regulatory requirements and supply chain complexities. Import regulations, trade policies, and quality control measures impact the availability and cost of ethnic food products.

11. Sustainability and Ethical Sourcing:

Consumers are increasingly concerned about sustainability and ethical sourcing of food products. Ethnic food brands that focus on sustainable practices, fair trade, and ethical sourcing can appeal to environmentally conscious consumers.

Segments

Based on Type

Indian Cuisine

Latin American cuisine

Mediterranean Cuisine

Middle Eastern cuisine

African Cuisine

Chinese Cuisine

Southeast Asian Cuisine

Based on product

Frozen ethnic foods

Sauces and Conditions

Snacks

Bakery and Confectionery

Beverages

Spices and herbs

Pulses, rice, noodles, and soups

Based on the distribution channel

Supermarkets/Hypermarkets

Specialty Stores

Online Retail

Foodservice (HoReCa)

Others

Browse the full report – https://www.credenceresearch.com/report/us-ethnic-food-market

Browse our Blog: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/us-ethnic-food-market-report-opportunities-challenges-6fwbf

Contact Us:

Phone: +91 6232 49 3207

Email: [email protected]

Website: https://www.credenceresearch.com

0 notes

Text

Unveiling the Beauty: Top Picnic Areas in China for Nature Lovers

China, known for its rich cultural heritage and breathtaking landscapes, offers an array of picturesque picnic spots that are perfect for nature enthusiasts and outdoor lovers. Whether you prefer lush greenery, tranquil lakes, or towering mountains, China boasts an abundance of scenic locations ideal for a relaxing picnic getaway. Here are some of the top picnic areas in China that promise a memorable outdoor dining experience:

1. West Lake, Hangzhou: Renowned for its serene beauty and romantic ambiance, West Lake in Hangzhou is a popular choice for picnickers. With its willow-lined banks, scenic pagodas, and tranquil waters, this UNESCO World Heritage Site offers a peaceful setting for enjoying a meal amidst nature's splendor.

2. Yulong River, Yangshuo: Nestled amidst the karst peaks of Yangshuo, the Yulong River provides a charming backdrop for a riverside picnic. Rent a bamboo raft or simply find a quiet spot along the riverbank to savor delicious local delicacies while soaking in the breathtaking scenery.

3. Mount Huashan, Shaanxi: For adventure-seekers looking for a unique picnic experience, the breathtaking summit of Mount Huashan beckons. After a thrilling hike along the infamous plank walk, find a secluded spot with panoramic views of the surrounding peaks to enjoy a well-deserved picnic feast.

4. Jiuzhaigou Valley, Sichuan: Known for its crystal-clear lakes, colorful forested slopes, and cascading waterfalls, Jiuzhaigou Valley offers a picturesque setting for a nature-inspired picnic. Pack a basket of local snacks and immerse yourself in the tranquility of this UNESCO World Heritage Site.

5. Fenghuang Ancient Town, Hunan: Step back in time and enjoy a historical picnic in the charming Fenghuang Ancient Town. Wander along the cobblestone streets lined with traditional wooden houses, then find a spot by the Tuo River to savor a meal while taking in the old-world charm of this ancient town.

Whether you're seeking a leisurely lakeside picnic or an adventurous mountaintop dining experience, China's diverse landscapes offer a myriad of picnic areas to suit every taste. So pack your picnic basket, gather your loved ones, and embark on a culinary adventure surrounded by the natural beauty of China's most stunning picnic spots.

0 notes

Text

How Special The Traditional Chinese Cuisine Is?

Here is a 1269 character post on how special traditional Chinese cuisine is:

Traditional Chinese cuisine possesses an abundant and profoundly rich culinary heritage that spans thousands of years. The eight major regional cuisines of China - Shandong, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangdong, Sichuan, Hunan and Anhui - have developed uniquely based upon available local ingredients and cooking styles perfected over centuries. What makes Chinese cuisine truly special is how skillfully it balances flavor profiles using sauces and cooking methods to bring out ingredients' natural qualities.

Through trial and error over millennia, ancient Chinese chefs discovered ways to make even the most humble ingredients taste utterly sublime. For example, mastering the boiled-then-wok techniques for cooking vegetables ensures they retain vibrant color and nutrients while absorbing subtle aromas. Stir-frying in countless lo - xu41b3qafu

0 notes

Text

Soy Sauce: Salty Misconceptions

As an Asian American woman, I have grown to connect with and appreciate my heritage through food. While I enjoy fried chicken and steak, I also enjoy having a nice bowl of 牛肉面 (niu rou mian=beef noodle soup) and 米粥 (mi zhou= rice congee). Despite indulging in both American and Chinese cuisines, I was brought up with the notion that to have real Chinese food, one had to go to Asian grocery markets and Chinese restaurants. Simply put, going to Panda Express or Walmart was a sin in my house. For my anthropological fieldwork grocery project, I chose to investigate how soy sauce, a preconceived international food by Western consumers, is marketed on American shelves.

Soy sauce (shoyu in Japanese) originated in China roughly 2,200 years ago and is believed to have been introduced to Japan by a Buddhist monk in the mid-13th century (Stein and Shibata). It is made from soybeans, wheat, salt, and water that is fermented in a four year process. The ingredients are not the make it or break it of a good soy sauce, but rather its production environment. Traditional Japanese brewers use koike or specially crafted wooden vessels to ferment the soybeans. The grains of the wood enrich the millions of microbes that deepen the fermentation to produce a savory umami flavor.

However, most modern-day soy sauces are produced within stainless steel vats that shorten the multi-year fermenting process to just three months. Because the bacteria produced in koikes cannot survive in steel tanks, many commercial companies pump their soy sauces with additives like monosodium glutamate or MSG in order to keep up with the demand and production of soy sauce--something I would discover to be true during my project.

During the spring of 2019, I examined soy sauce brands across 4 grocery stores in the Washington, D.C. area. My research was conducted through participant observation, which involves walking around the store as a potential customer and observing the ambiance of the store and its customers, while taking note of the location and sensory details of the soy sauce options offered. I conducted optical research as I observed my surroundings without personal interviews. Over the course of a semester, I learn that soy sauce, in its labeling and aisle surroundings, has been modified to fit into Western perceptions of Asian cuisine--revealing deeper connotations behind its ingredients and authenticity.

My first store visit was at the Whole Foods Market in the Foggy Bottom campus of the George Washington University. I paid close attention to the logos of each brand, nitpicking the logos for its embodiment of Asian culture through symbols like bamboo shoots and cranes. I later observed the design was not the most striking element, but rather the emphasis on reduced sodium and non-GMO ingredients.

Every bottle addressed it through writing, logos, or both. Health reasons aside, I came into this project with a preconceived notion that buying soy sauce from an American grocery store equated to not only buying from a market that addressed negative connotations of an Asian cuisine but also one that implied Chinese manufacturers were careless for placing MSG in their products.

Talk of Asian cuisine being too salty or not healthy for consumers was rarely discussed in my family nor did Asian food markets I went to as a child address it in the labelling. Seeing this language on American-brand soy sauce bottles made me feel culturally isolated as someone who had Chinese food almost every day of her life.

I visited Hana Japanese Market to see if the same language of reduced sodium appeared on its bottles. Hana Market is on the first floor of a quaint gray townhouse in a quiet neighborhood on U Street. I not only found Japanese-imported soy sauce on the bottom shelf, but also the American brands with reduced sodium and non-GMO stickers were on the shelf above. I was shocked to see the overall bottom placement of a renowned Japanese seasoning staple.

I wondered if it was because Hana’s store owners tailored their products towards the perceptions of Western customers--fully aware that MSG was a health concern and they had made efforts to address it. They even printed out English labels that said reduced sodium for the bottles written in Japanese. On an eye-level shelf, Hana offered ponzu or citrus “seasoned” (not flavored) soy sauce. I had never heard of ponzu until this site visit. To see traditional and authentic Japanese products at Hana made me feel more part of the Japanese culture and where we were borrowing this Asian cuisine from.

Visiting Safeway and Streets Market was a pivotal point in my research. The Safeway I visited in Georgetown was a superstore that focused on convenience and value. However, I was quickly appalled by the selection of soy sauces at Safeway. The soy sauces at Safeway were found in the “Asian/International” section. In the collage below, Safeway had big jugs of soy sauce that reminded me of gallons of gasoline. All options had cheap prices of $2-4. While the prices were tempting, La Choy proved that the quality was not worth it.

The bottle said “Inspired by Traditional Asian Cuisine”, yet its ingredients of hydrolyzed soy protein, corn syrup, caramel coloring, and potassium sorbate (a preservative) were quite the contrary. Might I add it was also produced in Omaha, Nebraska. After seeing the natural and traditionally brewed bottles that Whole Foods and Hana offered, La Choy was an insult to the traditional Japanese soy sauce brewers and the Asian culture itself.

Streets Market revealed a different connotation to how soy sauce was marketed. The store was located in a busy part of D.C., near the border of the Northeast sector. Prices at Streets were sky-high, yet the instant ramen noodles and ready-made “Asian” meals surrounding the soy tiny bottles of soy sauce did not portray Asian food as appealing. Streets perceived Asian food as an on-the-go and quick bite rather than a cuisine to be appreciated.

Perhaps this perception was why it took me 3 stores to locate a place with more than one type of soy sauce. Prior to Streets, I visited Trader Joe’s, Dean & DeLuca, and GWU’s Gallery Market only to discover they had one option. A bottle of soy sauce is not something to be consumed in a day, but I expected more variety. After my visit at Streets, with its array of plastic bowled and preservative-filled instant noodles, perhaps the purpose of soy sauce to Western consumers was nothing more than just a condiment that was put on things to make them saltier.

I went back to the Foggy Bottom Whole Foods for my final site report and was glad to see the wide selection of soy sauces with no worries of added preservatives. It gave me a greater appreciation for the store’s strides towards lower prices and high quality standards.

Above all, the Asian culinary identity was present in its surroundings and labelling. The International aisle lived up to its name as the soy sauce was next to Asian ingredients rather than instant bowls of ramen. Offering actual ingredients encouraged customers to make Asian dishes themselves, allowing for a greater appreciation of the Asian culture they are consuming. The labelling of bottles like San-J educated customers on the usage and meaning behind soy sauce.

My fieldwork has lead me to draw two conclusions on the implications surrounding the culture of Asian food in America. First, Asian cuisine is modified to fit the tastes of the” average American consumer”. Dishes like Kung Pao or General Tso’s chicken would never be found in China. When Panda Express was established in 1983, the Cherng family knew it would be difficult to for mainstream American customers, especially outside of metropolitan areas, to accept a Chinese dish in its original form and flavor (Liu, 138). Although its original flavor was salty and spicy, Andrew Cherng invented a new sweet and spicy orange sauce for chicken which allegedly came from Hunan cuisine in South China.

In addition, the famous P.F. Chang’s restaurant chain was named after restaurateurs Peter Flemming (PF) and Philip Chiang. However, “Chiang” was purposely changed into “Chang” in order to make the brand less foreign to the American public (Liu, 130). For many years, authentic Chinese food has had no market in America--pointing to a dangerous conception among many Americans that Chinese product owners are not in control of their own culture in the American food market. At the same time, food is both a culture and commodity. When food becomes a commodity, it is no longer an inherited culture as corporate America can easily appropriate it from the Chinese community (Liu 135).

Second, the use of MSG instead of soybeans in soy sauce points to a loss of authenticity in Japanese culture. The health dangers of replacing soybeans with artificial flavoring first occurred in the mid 20th century when Chairman Mao seized control of China in 1949. Perceptions of the Chinese changed as they were seen as threatening to US democracy. The association between Chinese food and health problems was an easy connection for Americans to adopt the Chinese Restaurant Syndrome or CRS (Germain, 2). People complained of having numbness in the back of the neck that gradually carried through the arms and back, leading to overall weakness.

CRS confirmed a pre-existing unease regarding the Chinese people during that time. Although MSG is also commonly used by manufacturers of processed foods like Doritos and KFC, it is inextricably tied to Chinese food. The consequences of CRS remain today, as demonstrated in my research, virtually almost all soy sauce bottles in the US have some sort of reduced sodium or no-MSG identification.

This project has taught me to appreciate the authenticity rather than the convenience of an international food. Culinary culture is a public domain in where everyone has the right to access or own it. Yet grocery stores need to remember that culture cannot be separated from tradition. It has to be respected. From the item’s placement in a store and on shelves, to its surroundings and design, more stores need to pay tribute to the culture from which their products migrate. Essentially, mixing caramel coloring, preservatives, and water is not Asian cuisine. And on that salty note, I sign off.

-- Caitlyn Phung

References

Liu, H. (n.d.). Who Owns Culture? In From Canton Restaurant to Panda Express: A History of Chinese

Food in the United States (pp. 128-145). Rutgers University Press.

Germain, Thomas. A Racist Little Hat: The MSG Debate and American Culture. Columbia Undergraduate Research Journal. 2017; 2:1. doi: 10.7916/D8MG7VVN

Stein, E., & Shibata, M. (2019, February 26). Is Japan losing its umami? Retrieved April 20, 2019,

from http://www.bbc.com/travel/gallery/20190225-a-750-year-old-japanese-secret

#authenticity#tradition#resepct#culinarycuisine#education#empowerment#encourage#commodity#MSG#reducedsodium#healthy#glutenfree#marketing#surroundings#aisles#international#asianfood#asian#Japanese#Chinese#cuisine#soysauce#soy#365#WFM#WholeFoods#foggybottom#gwu#HanaMarket#Safeway

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 10 Most Beautiful Towns In China(new update)

The 10 Most Beautiful Towns In China

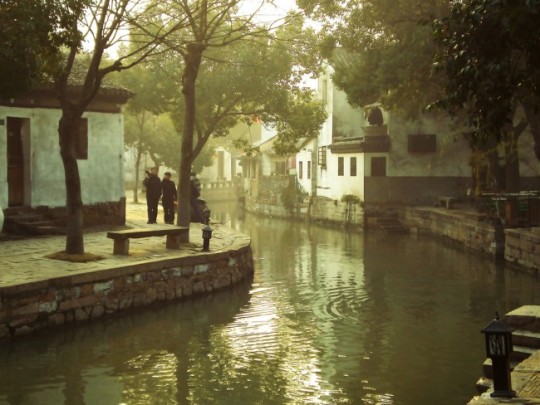

Zhouzhuang Often referred to as the ‘Venice of the East’, Zhouzhuang – located in between Shanghai��and Suzhou in China’s Jiangsu province – is one of the country’s most beautiful water towns. Simply walking the town’s pretty streets and the charming stone bridges that cross its rivers and waterways is a pleasure in itself. But the 900-year-old town is also home to plenty of sights bound to please history buffs. These sights include Zhang Ting – a sprawling, Ming Dynasty era residence home to six courtyards and more than 70 rooms – and Quanfu Temple, a beautiful Buddhist temple nestled on the edges of Baixian Lake. Zhouzhuang, China

Zhouzhuang, China | © Caitriana Nicholson/Flickr Fenghuang Nestled at the foot of verdant mountains on the edges of the Tuojiang River, Fenghuang was hailed as the most beautiful town in China by New Zealand-born writer and political activist Rewi Alley. The ancient Hunan town is home to many Miao people whose customs and culture can be seen everywhere. There are traditional stilted wooden houses, or ‘diaojiaolou’, along the river and batik printed cloths sold in its stores alongside local culinary delicacies like spicy pickled red peppers and ginger candy. Meanwhile local historical sites of note include Huang Si Qiao Castle – built in 687 and China’s best preserved stone castle. It is located a few kilometers west of town. Fenghuang, China

Fenghuang, China | © melenama/Flickr Heshun Over in western Yunnan not far from the Burmese border lies the small, remote town of Heshun, home to just 6,000 people. A former stop-off on the Southern Silk Road, also known as the Tea Horse Road, many of Heshun’s earlier residents took advantage of its location and travelled abroad. They built splendid houses mixing both Chinese and foreign architectural styles when they returned. This can still be seen in the town today. Walking its pretty cobblestone streets, visitors will come across local sights like Heshun Library, one of the country’s biggest rural libraries. There is also a memorial to Chinese philosopher Ai Siqi. Heshun, China

Heshun, China | Courtesy China Highlights Shiwei Quite far off the beaten track is Shiwei – a tiny frontier town in northeastern Inner Mongolia on the border with Russia. A cultural enclave for the country’s Chinese-Russian minority, the town’s mixing of cultures is evident everywhere. It can be seen from its architecture – beautiful Russian-style log houses known as ‘mukeleng’ – to its local food, which combines recipes Chinese shao kao barbecue and Russian lie ba bread. The town is surrounded by vast and verdant grassland. One of the best ways to explore it and the neighboring area is on horseback. Shiwei, Inner Mongolia, China Yangshuo Famed for the dramatic karst mountains that surround it, Yangshuo is a vibrant, tourist-friendly town nestled on the banks of the Li River in southern China’s Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. Though the town has seen a boom in visitors in recent years, Yangshuo has managed to retain its historic character. Its modern restaurants and stores are concentrated around West Street, the town’s main drag and its oldest dating back more than 1,400 years. Among them, visitors will find plenty of traditional architecture and charm. Indulge in some slow travel and catch a boat down the Li River from neighboring Guilin. It’s undoubtedly the most scenic way to arrive in Yangshuo. Yangshuo, China

Yangshuo, China | © David Boté Estrada/Flickr Tongli Another of Jiangsu’s picturesque water towns, Tongli is an idyllic little town just a short journey west of Zhouzhuang. Surrounded by five lakes and crisscrossed by canals, Tongli is made up of seven islands with a total of 49 bridges (of which the majority are a century or more old) linking the town together. Hire a gondola and see the pretty town from the water. But make sure to stop off at the Tuisi Yuan (Retreat and Reflection Garden) – part of the Classical Gardens of Suzhou. These were added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2000 and is a beautiful spot worth taking a detour for. Tongli, China

Tongli, China | © Ginny/Flickr Dunhuang An oasis in the barren expanse of the Gobi Desert, is the small northwestern town of Dunhuang. Formerly one of the most important stopping points along the Silk Road, this place is a haven for history buffs. There are no less than 241 historic sites of note dotted in and around the town. Just outside the town, visitors will find the White Horse Pagoda. This was believed to have been constructed in 382 to commemorate the horse of Buddhist monk that carried Buddhist scriptures from Kucha to Dunhuang. Nearby is the Mogao Caves – a UNESCO World Heritage Site home to a treasure trove of Buddhist art. Dunhuang, China

Mogao Caves, Dunhuang, China | © Laika ac/Flickr Gulangyu Island A small isle located a short boat ride from the city of Xiamen, Gulangyu Island gets its name from two Chinese words – ‘gu’ meaning drum and ‘lang’ meaning waves – and is so-called for the drum-like sounds the tide makes when it hits the reef that surrounds the island. A tranquil retreat from the busy nearby city, Gulangyu is listed by the China National Tourism Administration as an AAAAA Scenic Area. It was formerly an international settlement and is noted for its beautiful colonial, Victorian-style architecture. Home to China’s only Piano Museum, the town’s other must-see local sights include the beautiful Shuzhuang Garden. Meanwhile a trip up Sunlight Rock – the Gulangyu’s highest point – offers breathtaking views over the island and coastline. Gulangyu Island, China

Gulangyu Island, China | © SaraYeomans/Flickr Hongcun Film buffs might recognize Hongcun, an ancient Anhui village nestled in the mist-shrouded foothills of Huangshan Mountain, from Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. Home to some of China’s finest Ming and Qing Dynasty architecture, the village provided a befittingly historical and mystical setting for several scenes from the Oscar-winning film. Much of the village – which, alongside neighboring Xidi, was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2000 – centers around its half-moon shaped pond. Local sights include Chengzi Hall, a grand residence built in 1855. This place has ornate wood and stone carving and now acts as a museum, which is open to visitors. Hongcun, China

Hongcun China | © Thomas Fischler/Flickr Dali Dali is a beautiful old town nestled on the edges of Erhai Lake famed for its natural beauty and stunning locally mined marble. Grand city gates welcome visitors to the town and give way to cobbled streets home to a host of beautifully preserved traditional Bai folk houses. The Three Pagodas of Chongsheng Temple – dating back to the 9th and 10th centuries – are a sight to behold. Plenty of authentic handicrafts, from artwork made of local marble to embroidered Bai cloths, are available to purchase on the streets. Another Dali must-do is the three-course tea – a Bai tradition of greeting guests with courses of bitter, sweet and ‘aftertaste’ tea. Dali, China

Dali, China | © tak.wing/FlickrSave to Wishlist

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Kuala Lumpur’s Choice Chinese Cooking

Chomp your way through the Malaysian capital’s storied eateries.

The city blocks are chock-full with heritage eateries and roadside stalls. On a single outing visitors will most likely see satay (top left) licked by flames, the vermillion skin of Peking duck (top right), chopsticks pull at a tangle of beef noodles (bottom left), and billows of hot air coursing out of behemoth bamboo steamers holding a trove of dim sum (bottom right). Photos by: Julian Manning

Plumes of cigarette smoke rise like white ribbons, coiling amidst the clamour of Kuala Lumpur’s Chinatown. What incense is to Tao temples, cigarettes are to these streets. Warm notes of roasted chestnuts are replaced by the beer-soaked breath of elderly men quarrelling in Cantonese as I walk down Petaling Road—the spine of a neighbourhood predominantly made up of Chinese immigrants new and old, and throngs of tourists eager to eat.

Some people insist that Chinatowns are the same everywhere. They are, simply, wrong. From haggling over sweet pork sausages in Bangkok to rolling dice over whisky shots in San Francisco, in my experience, Chinatowns are far from cookie cutter replicas of each other. And if I had to choose one in particular to challenge that ill-informed notion, it would be the wonderfully scruffy streets of KL’s Chinatown.

Cherry-red arches and faux Yeezys on ‘discount’ hardly define the area. Cooks are the core of the community, whether they don a sweat-stained ganji or a double-breasted chef’s jacket, and you will realise as much walking down the streets. The culinary roots of this Chinatown’s inhabitants spread out in a tangle, like that of a banyan tree. Baba-Nyona cuisine, also known as Peranakan cuisine, is a mix of influences from early Chinese immigrants who integrated themselves with the local Malays. They are represented by dishes like beef rendang and nasil emak, the latter a medley of coconut milk rice, sambal, fried anchovies, a boiled egg, with the typical addition of chicken. Later waves of immigrants brought along delicacies from their respective regions: char siu pork and dim sum of the Yue cuisine, porridges of Fujian or Hookien cuisine, and the much-coveted Hainanese or Hunan chicken rice, to name a few. In the bylanes of this bustling quarter, culinary traditions stick to these streets like the patina of a well-used wok.

Here, vermilion-hued ducks hang from hawker stands, glowing like the gauze lanterns that line the streets, outshined only by flames dancing below clay pots filled with golden rice and morsels of chicken, fish, and lap cheong sausages. Each stall and station is manned by a master of their craft. Plastic chairs become portholes to skewers laden with charcoal grilled meat and bowlfuls of fragrant asam laksa, wafting tangy notes of tamarind, the broth waiting to be swiftly slurped up.

Finding a memorable meal in KL’s Chinatown is as easy as promenading down its central streets. A hot jumble of thick hokkien mee noodles have been a staple at Kim Lian Lee for decades, the once-upon-a-time stall now a two-storey tall institution. Just across the street is Koon Kee, another neighbourhood stalwart serving up their popular wan tan mee, char siu pork-topped Cantonese noodles tossed in a sweet black sauce, served with pork and shrimp dumplings. And just down Madras Lane (the street’s name has officially been changed, but locals still use its original title) lies a long line for yong tau foo, tofu typically stuffed with minced pork and fish paste, which has had customers queuing up for over 60 years. The catch? In this hubbub, it is all too easy to miss some of the less central but equally important eateries.

This storied assortment of kopitiams (coffee shops), family restaurants, and outdoor stalls from the halcyon days of Chinese culinary influence in Kuala Lumpur are tucked away from the bustle, a few even mapped outside of the boundaries of Chinatown. So if your palate craves a bit of the past in the present, weave in and out of Chinatown and explore restaurants where the same dishes have been served up for decades, for very good reasons.

1. Sang Kee

Est. 1970s

Address: 5A, Jalan Yap Ah Loy, City Centre

At dinner time Chinatown’s sidewalks (top) turn into a menagerie of meals. Chef Won San (bottom) gets to work on an order of freshwater prawn noodles. Photo by: Julian Manning

Sang har mee, or freshwater prawn noodles, are quite the treat in KL. The best sang har mee places are typically stalls, yet they do not come cheap, the most popular joints serving up the dish from anywhere between RM50-90/Rs835-1,500. Even though the portions are usually enough to fill two people, for those kind of prices you want to be sure you’re indulging in the best sang har mee in the neighbourhood.

Tucked in a discreet alleyway in the shade of pre-World War II buildings, on a little lane where late night courtesans would once congregate, lies Sang Kee. For over four decades this open air kitchen has been serving up some of the best freshwater prawn noodles in KL.

Those interested in a performance can inch up in front of the old man behind the wok and watch him work his wizardry, he doesn’t mind. Two beautifully big freshwater prawns are butterflied and cooked in prawn roe gravy, stirred in with egg, slivers of ginger, and leafy greens. Wong San, the chef, understands his wok like Skywalker understands the force—meaning, the wok hei (wok heat or temperature) is on point.

Once on your plate, plucking a plump piece of prawn out of the open shell is an easy feat. The fresh and supple meat is charged with the gravy, bite into it, and a flash flood of flavour courses out. In KL most versions of sang har mee sport crisp, uncooked yee mee noodles, which are then drenched in the prawn-imbued sauce. A lot of people love ’em this way, but I personally feel this gives the noodles the texture of a wet bird’s nest. Sang Kee’s noodles are cut thick, boiled, and then stir-fried, coated with oodles of scrambled egg, a style that lets the prawn’s flavours permeate every bit of the dish. At Sang Kee, for most folks a single p

ortion is enough for two at RM65/Rs1,085 a plate, but if that’s too steep a price, you can get the dish made with regular prawns for significantly less.

2. Soong Kee Beef Noodles

Est. 1945

Address: 86, Jalan Tun H S Lee, City Centre

The fine people at Soong Kee have been serving up beef noodles since World War II, and the product speaks for itself. It’s always crowded at lunchtime, but don’t worry about waiting around too long. Usually a server will squeeze you in at one of the many large round tables with plenty of neighbours who don’t mind the company. I love this approach because it means you get a good look at what your table-mates are munching on. That being said, newcomers should inaugurate their Soong Kee experience with beef ball soup and beef mince noodles—simple but hearty dishes that will give you a good idea of why the place has stuck around (small bowl of noodles from RM7/Rs120).

3. Sek Yuen

Est.1948

Address: 315, Jalan Pudu, Pudu

Mealtimes beckon travellers to dig into bowlfuls of beef ball soup (bottom left), pluck of piping hot scallop dumplings (middle left), and perhaps chow down on a myriad of meat skewers (top right). For dessert, munch on crunchy ham chim peng (bottom right), delicious doughnuts filled with red bean paste. If the flavour is too earthy for you, just pick up an entire bag of regular doughnuts (top left) or roasted chestnuts (middle right) from one of the city’s many street vendors. Photos by: Julian Manning

Sek Yuen is made up of three separate sections, spread out over adjacent lots a few feet from each other. One is being renovated, another is the original 1948 location, and the last is the crowded AC section built in the 1970s. I wanted to eat in the original section, but by the time I arrived the service was slowing down and everyone was dining in the AC section. When in doubt, follow the locals.

Two noteworthy staples of the restaurant, steam-tofu-and-fish-paste as well as the crab balls, were already sold out by the time I placed my order. So I happily went for the famous roast duck with some stir fried greens. The duck was delicious; the skin extra crispy from being air-dried, yet the meat was juicy with hints of star anise, which paired well with the house sour plum sauce. But what I enjoyed most was the people-watching. A Cantonese rendition of “Happy Birthday” played non-stop on the restaurant’s sound system for the entire 50 minutes I was there. The soundtrack lent extra character to the packed house of local Chinese diners, most of them regulars. To my right, a group of rosy-cheeked businessmen decimated a bottle of 12-year Glenlivet, and were perhaps the most jovial chaps I’ve ever seen. In front of me, a group of aunties were in party mode, laughing the night away with unbridled cackles. Perhaps the most entertaining guest was the worried mother who kept scurrying over to the front door, pulling the curtains aside to check if her sons were outside smoking. The sensory overload hit the spot. You could tell people were comfortable here, like it was a second home—letting loose in unison, reliving old memories while creating new ones.

I learned that when all sections of the restaurant are operational, Sek Yuen is said to employ around 100 people, many of whom have stuck with the restaurant for a very long time, just like the wood fire stoves that still burn in the kitchen (duck from RM30/Rs500).

4. Ho Kow Hainan Kopitiam

Est.1956

Address: 1, Jalan Balai Polis, City Centre

Although it has shifted from Lorong Panggung to the quieter Jalan Balai Polis, Ho Kow Kopitiam remains outrageously popular. Customers are for the most part locals and Asian tourists, unwilling to leave the queue even when the wait extends past an hour. In fact, there is a machine that manages the number system of the queue, albeit with the help of a frazzled young man whose sole job is telling hungry people they’ll have to wait a long time before they get any food. It’s safe to say the gent needs a raise. If you haven’t guessed already, get there early, before they open at 7:30 a.m.—otherwise you’ll be peering through the entrance watching the best dishes get sold out.

Many tables had the champeng (an iced mix of coffee and tea), but I’m a sucker for the hot kopi (coffee) with a bit of kaya toast, airy white toast slathered with coconut egg jam and butter; treats good enough to take my mind off of waiting for an hour on my feet. I then dove into the dim sum, and became rather taken by the fungus and scallop dumplings. The curry mee, whether it is chicken or prawn, was a very popular option as well. When it comes to dessert, the dubiously-named black gluttonous rice soup sells out fast, which devastated the people I was sharing my table with.

They also serve an assortment of kuih for dessert, including my personal favourite, the kuih talam. It is a gelatinous square made up of two layers—one green, one white. They share the same base, a mixture of rice flour, green pea flower, and tapioca flour. The green layer is coloured and flavoured by the juice of pandan leaves, and the white one with coconut milk. For someone like myself, who doesn’t have a big sweet tooth, the savoury punch, balanced by a cool, refreshing finish make this dessert a quick favourite (kaya toast and coffee for RM5.9/Rs100).

5. Kafe Old China

Est. 1920s

Address: 11, Jalan Balai Polis, City Centre

A relic from the 1920s, the Peranakan cuisine at Old China continues to draw in guests. The ambience seems trapped in another era, as is the food, in the best way possible. Post-modern, emerald green pendant lamps, feng shui facing windows, and old timey portraits make up the decor. A meal here is not complete without the beef rendang, hopefully with some blue peaflower rice. It is also one of the few places to get a decent glass of wine in Chinatown (mains from RM11/Rs190).

6. Cafe Old Market Square

Est. 1928

Address: 2, Medan Pasar, City Centre

Kuala Lumpur skyline (top left) lies adjacent to the low-slung Chinatown neighbourhood (bottom right); A regular customer looks inside the original Sek Yuen restaurant (bottom left); Cooked on charcoal, the traditional clay pots brim with chunks of chicken, slivers of lap cheong (Chinese sausage), and morsels of salted fish (top right). Photos by: Julian Manning (food stall, woman), BusakornPongparnit/Moment/Getty Images (skyline), f11photo/shutterstock (market)

There is something incredibly satisfying about cracking a half boiled egg in two at this café, the sunny yolk framed by a cup of kopi, filled to the point the dark liquid decorates the mug with splash marks, and slabs of kaya toast. Despite a new lick of paint, I could feel the almost 100 years of history welling out of the antique, yellow window shutters lining the three storey facade of the building, the last floor operating as the café’s art gallery.

This place won me over as the perfect spot to read my morning paper, everything from the high-ceilings to the petit bistro tables allowed me to pretend I was in another era—a time when people still talked to each other instead of tapping at their smartphones like starved pigeons pecking at breadcrumbs. Yet, the best time to see this place in its full form is post noon, when the lunch crowd buzzes inside. Droves of locals cluster in front of the nasi lemak stand placed inside the café, hijabs jostling for the next plate assembled by an unsmiling woman with the unflinching demeanour of a person who has got several years of lunchtime rushes under her belt (lunch from RM6.5/Rs110, breakfast from RM1/Rs17).

7. Capital Cafe

Est. 1956

Address: 21, Jalan Tuanku Abdul Rahman, City Centre

Beneath the now defunct City Hotel, Capital Cafe is your one-stop satay paradise. The cook coaxes up flames from a bed of charcoal with a bamboo hand fan, using his other hand to rotate fistfuls of beef and chicken skewers liberally brushed with a sticky glaze. The satay is a perfect paradox, so sweet, yet so savoury; the meat soft, but also blistered with a crisp char. This snack pairs wonderfully with hot kopi—perhaps because it cuts the sweetness—served by a couple of uncles brimming with cheeky smiles and good conversation (satay from RM4/Rs70).

8. Yut Kee

Est.1928

Address: 1, Jalan Kamunting, Chow Kit

Like many of KL’s golden era restaurants, Yut Kee moved just down the road from its original location. Serving Hainanese fare, like mee hoon and egg foo yoong, with a mix of English and Malay influences, YutKee has remained one of the most famous breakfast joints in all of KL for almost 100 years. At breakfast it features an almost even mix of locals and tourists, the former better at getting to the restaurant early to snag their regular tables.

During peak breakfast hours, waiters slap down face-sized slabs of chicken and pork chops, bread crumbed and fried golden brown, sitting in a pool of matching liquid gold gravy, speckled with peas, carrots, and potatoes. You can’t go wrong with either one. If your gut’s got the girth, follow up a chop with some hailam mee, fat noodles tossed with pork and tiny squid.

On weekends guests also get the opportunity to order two specials, the incredible pork roast and the marble cake. A glutton’s advice is to take an entire marble cake away with you. By not eating it there you save room for their seriously generous portions. The cake also lasts up to five days, which gives you about four more days than you’ll actually need. Plus it makes for a perfect souvenir, especially since the Yut Kee branded cake box is so iconic.

One of the many delighted people I gave a slice of cake to back home hit a homerun when they put into words what was so special about the marble cake: “It’s not super fancy, with extra bells and whistles, but it tastes like what cake is supposed to…like something your grandma would make at home.” As he said the last words he reached for another sliver of cake (chicken chop is for RM 10.5/Rs180, a slice of marble cake is for RM1.3/Rs20).

(function(d, s, id) var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0]; if (d.getElementById(id)) return; js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id; js.src = "http://connect.facebook.net/en_US/sdk.js#xfbml=1&version=v2.5&appId=440470606060560"; fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs); (document, 'script', 'facebook-jssdk'));

source http://cheaprtravels.com/kuala-lumpurs-choice-chinese-cooking/

0 notes

Text

Shanghai – China’s largest city and its principal port, located at the mouth of the Yangtze River delta. Shanghai’s heritage is very mixed given its role as a major trading city, especially as China opened up to international maritime trade in the 18th century onwards. Much of this was forced on the declining Qing Dynasty mostly in the mid-19th century by Western powers via the “Unequal Treaties,” which remain a sensitive point to this day. The expulsion of the various foreign occupiers in the 1949 revolution and subsequent relative isolation of the city through the 1980’s by the victorious Communist regime preserved much of this environment.

Shanghai Business District – East Bank of the Huangpu River

Like many large commercial cities, it’s a fascinating place to visit with plenty to see, and is an excellent base for other China travel. The main issue is that you need to obtain a China entry visa.

Huangpu Neighborhood

Shanghai’s main city area is centered around People’s Square, a large park that also holds some museums, with largely residential districts to the west and the business district to the east. The eastern area is bordered by Shanghai’s famous Bund waterfront on the Huangpu River, with a concentration of unspoiled Art Deco era buildings that is hard to find except in other cities that grew rapidly in the mid-20th century, such as Detroit: https://wp.me/p7Jh3P-nP

The Bund

Shanghai’s layout reflects the two main 19th-20th century foreign settlements – the International Settlement (to the UK and USA) in the east along the riverfront (largely in the eastern part of the Huangpu District); and the French Concession, which runs to the southwest of People’s Square along Huaihai Middle Road and the northern part of the Xuhui District. Just south of the former International Settlement and next to the river is the old city, that was originally a walled city and which remained separate from the International Settlement to the North.

You could easily spend 3-4 days in Shanghai and find plenty to do, especially if you have never visited mainland China before. There are some pedestrian-friendly neighborhoods within the former French Concession area such as the rather upmarket Xintiandi and Tianzifang areas. The old city (start at Yuyuan Garden metro) is south and east of Renmin Road and includes some isolated archaeological remnants and gardens. Here are some ideas of in-town things to do, as well as some area side trips that I’ll write about later.

The Shanghai Museum (People’s Square – south side). If you want an introduction to Chinese history and culture, the Shanghai Museum is equivalent to a national art museum. You can get the various imperial dynasties – going back over 2,000 years – outlined in your head through the extensive watercolor, pottery, currency and other collections. I have always wondered how much of China’s historical artifacts survived the Cultural Revolution in 1966, and notably some of the material came from overseas Chinese collectors. The museum is closed Mondays and has free entry.

There is interesting transitional currency with late 19th/early 20th century bills.

The Bund and Art Deco Shanghai. Manhattan on the Yangtze: Shanghai has a high level of preservation of its buildings from the late 19th through the mid-20th century, and was a major commercial center of East Asia for the first half of the 20th century. You could be downtown in a US city that grew around that time. There are plenty of online offerings for historical tours to understand this – see below, but book ahead. China had been dealing with invasion by Japan since 1931 and Shanghai was attacked by the Japanese in 1932 and then again in 1937, being occupied until 1945.

The main business area is located northeast of People’s Square towards to the Bund, with many of the major buildings lining the Bund. If you want to pick one place to see, the Peace Hotel, originally opened as the Cathay Hotel in 1929, has an impressive Art Deco ground floor area.

Eating Around. Without getting into the usual street food obsession, Shanghai Chinese cooking works very well if you are after something light and casual, and there are plenty of formal restaurants covering the main cooking styles of China. The Shanghainese post-revolution diaspora has meant that many Shanghai specials have worked their way into the Chinese repertoire. A few key types include:

Xiao Long Bao – Soup filled dumplings, usually pork or shrimp, but vegetarian options are common.

Shengjiang Mantou – oh yeah. Soup filled dumplings with a flakier pastry shell, fried around the base.

Hongshao Rou – braised pork belly. A favorite of Chairman Mao apparently, although there are varieties nationwide.

Jiaohua Ji – beggar’s chicken. Stuffed, marinated and roasted in a paper shell.

For the most part, restaurants catering to the local crowd often offer picture menus where the menu is in Chinese. The various city shopping malls usually have a restaurant level – these are usually quite good in Asia as they are clean, bright and air-conditioned, and not at all the usual chain debacle you get in the West. Some that are worth a visit include:

Da Hu Chun (11 Sichuan Street, Huangpu) – full range Shanghai classics.

Di Shui Dong (56 Maoming S Road, Jing’an) – Hunan specialty.

Din Tai Fung ( Jing’an) – actually a Taiwanese chain (whose founder fled China in 1948) featuring Shanghainese specials and known for it’s xiao long bao, but a good entry-level restaurant with a simple menu.

Lao Fan Dian (Fujou and Juixiaocheng Streets, Huangpu) – another Shanghai standard.

Lin Long Fang (10 Jian Guo Dong Lu or SML Center, Huangpu) – great local mini chain.

Nan Ling (1238 Yainan Middle Street, Jing’an) – more formal Shanghai classics.

Shanghai Grandmother (70 Fuzhou Road, Huangpu) – multi-level family style offering.

The French Concession. The French Concession is a more residential, retail and green area, largely north and south of Huaihai Middle Road as it heads southwest from People’s Square, which provides contrast to the more urban/shopping/office focus in the Huangpu/Bund area east of People’s Park. It is also close to the Jing’an temple, which is worth a visit. It has a more relaxed and leafy atmosphere, in part because the French built wider, tree-lined streets. As mentioned earlier, the Xintiandi (aim for the metro station of the same name) and Tianzifang (southwest of the Jianguo West and Sinan Roads intersection) areas are good walking destinations.

Jaywalking on Julu Road

Dance Evening at Xianyang Park

The Jing’an Temple. The Jing’an temple, northwest of the French concession with a metro next to it, is well with a visit, centered around a great hall with a seated Buddha. There has been a temple in the area since 247 CE, and one on the current site since 1216; it burnt down in the 1970’s and was rebuilt in the 1980’s so is quite new, although various artefacts, such as the medieval Hongwu bronze bell, date back a ways. There is a good park just south of the temple to take a break and admire the greenery.

Walking Tours. Shanghai’s sights are well distributed around the neighborhoods and there isn’t a concentration of major points, so a walking tour can be useful. Here are a few and of course Tripadvisor has a selection:

The Shanghai Historical Society focuses on the 19th and 20th century and their walking tours are here: https://www.historic-shanghai.com/events/

Shanghai Walking Tours: http://shanghaiwalkingtour.com/english/walking_tours.html

Culinary Backstreets is food focused: https://culinarybackstreets.com/culinary-walks/shanghai/

Side Trips. There are a few cities in the Yangtze delta that are worth visiting, such as Suzhou and Hangzhou, about 30 and 60 minutes away by rail, respectively. You can always look for a bus or tour service, although rail is good option, connecting into the metro at both cities. Suzhou is a compact medieval city better suited to a day trip, while Hangzhou and it’s famous lake and forested hill park are more for an overnight stay.

Suzhou

Closer in is the canal town of Zhujiajiao, located in the western outskirts of the city facing Lake Dianshan, at the metro stop of the same name.

Logistics. I stayed at the Mansion Hotel (Xinle and Xiangyang Roads, Jing’an) and the Jing’an Campanile (425 Wulumuqi North Road), in the French Concession and Jing’an areas, respectively. Both have proximity to the metro which is worthwhile here. The Mansion Hotel is a one of a set of smaller hotels restoring pre-war Shanghai mansions, here designed by French architects in 1932 for a Shanghai syndicate leader and opened in 2007.

Airports. Shanghai is served by two airports – Pudong (PVG), the newer principal international gateway located east of the city on the coast; and Hongqiao (SHA), the original secondary airport located west of the city. Both have Metro stations and are about 60 and 45 minutes from People’s Square respectively. Pudong is also served by a fast (300 km/h) Maglev line to the Longyang Road Station in the eastern suburbs. This may save you some time although as you will have to change to get to the center it may be simpler to just use the metro.

Metro. The Shanghai Metro is an excellent way to get around the city. You can purchase a range of passes at the airport station or at any of the station customer service centers. Apart from individual tickets, there are 1- and 3-day passes or alternatively you can just buy the Shanghai Public Transportation Card which starts at Y100 and includes a Y20 deposit refundable on return of the card. Note that the metro stations are quite large and also have a security check (including bag x-ray machine). As to cab and ride hailing alternatives, note that Uber does not operate in China – you can try the main Chinese provider, Didi Chuxing, but check online for the latest as far as obtaining an English version of the app. Logistically, note that all metro entrances have a security checkpoint (with baggage x-ray so don’t carry a bag unless necessary) before the ticket barriers.

The Shanghai Metro is Extensive

Rail. China’s high-speed rail system is comfortable, fast, cost-effective and well worth trying. The two main issues you should factor in include the high passenger volume it manages in a country of 1.4 billion people, and the airport-style security requirements at rail stations. This means you need to plan your journey and factor in time beforehand. Many trains are 100% occupied so unless you don’t mind a “standing” ticket, you should book in advance: trip.com is a useful website. Secondly, you will need your passport to buy or pick up your ticket, after which you will go through a security check (including baggage x-ray) where you will present your ticket and passport. The ticket is scanned again when you enter the platform via the boarding gate. If you book for a certain departure time, there will be a specific departure gate that usually open about 15 minutes pre-departure. If you allow 15 minutes to buy or pick up your ticket from the ticket office queue (there are self service machines with only Chinese language access), 15 minutes to enter the station, pass security and navigate to your gate, and then assume you get in line at the gate 15 minutes pre-departure, for your first time I would allow arriving at the station at least 45 minutes pre-departure. At post-journey arrival, at the larger stations you are sent through a separated (from the departures) arrivals level and put out into a pre-security area.

Hongqiao Railway Station Main Departures Hall

Shanghai has four rail stations, the more central Shanghai Rail Station, Hongqiao (out west near the airport), the South and West stations. Note that the ticket office at the central station is in a separate building across from the main entrance. At Hongqiao, the ticket office is post-security in the main departures hall. The ticket offices are typically busy however the lines move quite fast.

Rapidly Moving Ticket Line, Shanghai Train Station

Your Chinese Language Skills. Lack of Mandarin Chinese language skills is not much of an issue; all public signs are bilingual Chinese/English – even the metro ticket vending machines have an “English” button on their touchscreen displays. Since China’s schools have had English language training from about 8 years of age for some time now, English is more commonly spoken to some extent. However, you should still either pick up a basic language guide or go to the many Mandarin Chinese language Youtube offerings in advance of the trip.

Stuck for a Gift? The First Food Hall (720 Nanjing Road East) is worth going to for a one-stop that covers Chinese products. A four-storey supermarket and food court, it has the feel of something from the Communist era and so is worth going to. Nanjing Road East is the main shopping street, pedestrianized east of People’s Square.

Craft Beer. Craft beer has reached China, or at least it’s more expat and overseas travelled populations, and it’s worth trying. Not surprisingly, the main providers are mostly in the French Concession area and you should focus on:

Boxing Cat Brewery (82 Fu Xing Road West and (under refit in July 2019) 521 Fu Xing Middle Road. My favorite I have to say, with the very floral and moderately bitter Sucker Punch pale ale, the very solid TKO west coast IPA and the excellent King Louie imperial stout.

Liquid Laundry (Kwah Centre 2/F, 1028 Huaihai Middle Road). Gastropub owned by Boxing Cat and with a solid beer menu including other beers and their own line. Good pale ales and IPAs.

Shanghai Brewing Company (15 Dongping Road). Decent craft beer selection.

Stone Brewing Tap Room (1107 Yu Yuan Road). Not entirely local as the San Diego area brewery expands globally, but worth supporting.

Shanghai’d Shanghai – China’s largest city and its principal port, located at the mouth of the Yangtze River delta.

0 notes

Text

The St. Regis Changsha Hotel Opens in China

St. Regis Hotels & Resorts last week announces the opening of The St. Regis Changsha, the luxury hotel brand's eighth hotel in Greater China. Featuring a timeless blend of innovation and tradition, the hotel is set to elevate Changsha's luxury hospitality landscape with its uncompromising experience, signature St. Regis Butler Service, exceptional culinary venues and remarkable design. The St. Regis brand also expects to debut The St. Regis Shanghai Jing'an later this year, as well as four additional hotels in Greater China's gateway cities and leisure destinations over the next five years, further solidifying St. Regis' position as the preeminent luxury hospitality brand in the region. "The St. Regis Changsha represents yet another compelling milestone for the brand as we grow our portfolio of exquisite luxury hotels in the Greater China region," said Stephen Ho, Chief Executive Officer, Greater China, Marriott International. "We are thrilled to bring the iconic St. Regis experience to this important, historic destination which has seen tremendous growth in the tourism sector." "We are delighted to offer guests unmatched accommodations in one of the world's most exquisite cities and introduce the St. Regis brand's distinguished heritage to Changsha, elevating the local hospitality landscape to new heights," said Fiona Hagan, General Manager, The St. Regis Changsha. "We look forward to welcoming both international and Chinese guests alike, providing the famous St. Regis service hallmarks at this luxurious new address." The St. Regis Changsha is ideally situated in the capital city of the Hunan province in South Central China, nestled at the lower reaches of the Xiang River. Changsha enjoys a storied past, serving as one of the most important cities in China since the Qin Dynasty. An ideal destination for both business and leisure travel, Changsha has become a thriving commercial and manufacturing trade center, renowned for its striking landscapes and flourishing dining and entertainment scene. The St. Regis Changsha serves as the ideal departure point for travelers looking to be immersed in the city's historic local traditions. Guests can admire the city's historic craftsmanship of bronzeware, pottery, porcelain and calligraphy, as well as marvel at the panoramic views of the beautiful landscapes from the top of the nearby Yuelu Mountain. Owned by the Yunda Group, The St. Regis Changsha is housed in the heart of Yunda Central Plaza, on the 48th to 63rd floors in one of the city's tallest skyscrapers. The St. Regis Changsha also enjoys its own helipad on the 63rd floor, providing an exceptional way to arrive or depart to and from the hotel. Advertisement The St. Regis Changsha offers 188 exquisitely styled guest rooms and suites, boasting sweeping views of the city, forming a luxurious respite from the frenetic pace of urban life. The rooms are beautifully designed and decorated with subtle Chinese touches. Guests of The St. Regis Changsha enjoy the famed hallmark of the St. Regis brand – signature St. Regis Butler Service – which offers unparalleled, around-the-clock service by customizing each guest's stay according to their tastes and preferences. Trained in the English tradition, the St. Regis butler offers a range of services including unpacking and packing, beverage service, garment pressing and booking excursions and reservations. The St. Regis Changsha also offers guests the opportunity to relax at The St. Regis Athletic Club, located on the 63rd floor, which features an indoor swimming pool with a beautiful panoramic view and a 24-hour fitness center. The St. Regis Changsha offers six distinct culinary venues, where guests can dine and lounge while taking in the stunning views of the city below. At Social, guests enjoy the traditional St. Regis brunch as well as an extensive buffet and live cooking stations that truly bring the kitchen to life, while Yan Ting, a refined specialty Chinese restaurant, offers a mix of authentic Cantonese and Hunan cuisine. Guests can also choose to savor fine Japanese dishes at Un, before enjoying premium Chinese tea at the Tea Lounge. Gourmet coffees and vintage champagnes await at The Drawing Room, while the signature St. Regis Bar is an elegant space to indulge in premium wines, rare spirits and handcrafted cocktails such as the St. Regis brand's famous Bloody Mary or the hotel's signature Baijiu Mary featuring signature Hunan spices and local baijiu. The St. Regis Changsha's thoughtfully designed event and meeting spaces can accommodate any occasion from exquisite weddings to intimate business gatherings. The hotel's elegant main ballroom, which spans 1,888 sqm, accommodates up to 1,700 guests. The hotel also features a spacious 660 sqm foyer and eight distinct function rooms equipped with the latest technology. The St. Regis Changsha is offering special grand opening packages starting from CNY1,680 net per room per night with breakfast for one guest, valid until June 29th, 2017. Logos, product and company names mentioned are the property of their respective owners.

0 notes

Text

Kuala Lumpur’s Choice Chinese Cooking

Chomp your way through the Malaysian capital’s storied eateries.

The city blocks are chock-full with heritage eateries and roadside stalls. On a single outing visitors will most likely see satay (top left) licked by flames, the vermillion skin of Peking duck (top right), chopsticks pull at a tangle of beef noodles (bottom left), and billows of hot air coursing out of behemoth bamboo steamers holding a trove of dim sum (bottom right). Photos by: Julian Manning

Plumes of cigarette smoke rise like white ribbons, coiling amidst the clamour of Kuala Lumpur’s Chinatown. What incense is to Tao temples, cigarettes are to these streets. Warm notes of roasted chestnuts are replaced by the beer-soaked breath of elderly men quarrelling in Cantonese as I walk down Petaling Road—the spine of a neighbourhood predominantly made up of Chinese immigrants new and old, and throngs of tourists eager to eat.

Some people insist that Chinatowns are the same everywhere. They are, simply, wrong. From haggling over sweet pork sausages in Bangkok to rolling dice over whisky shots in San Francisco, in my experience, Chinatowns are far from cookie cutter replicas of each other. And if I had to choose one in particular to challenge that ill-informed notion, it would be the wonderfully scruffy streets of KL’s Chinatown.

Cherry-red arches and faux Yeezys on ‘discount’ hardly define the area. Cooks are the core of the community, whether they don a sweat-stained ganji or a double-breasted chef’s jacket, and you will realise as much walking down the streets. The culinary roots of this Chinatown’s inhabitants spread out in a tangle, like that of a banyan tree. Baba-Nyona cuisine, also known as Peranakan cuisine, is a mix of influences from early Chinese immigrants who integrated themselves with the local Malays. They are represented by dishes like beef rendang and nasil emak, the latter a medley of coconut milk rice, sambal, fried anchovies, a boiled egg, with the typical addition of chicken. Later waves of immigrants brought along delicacies from their respective regions: char siu pork and dim sum of the Yue cuisine, porridges of Fujian or Hookien cuisine, and the much-coveted Hainanese or Hunan chicken rice, to name a few. In the bylanes of this bustling quarter, culinary traditions stick to these streets like the patina of a well-used wok.

Here, vermilion-hued ducks hang from hawker stands, glowing like the gauze lanterns that line the streets, outshined only by flames dancing below clay pots filled with golden rice and morsels of chicken, fish, and lap cheong sausages. Each stall and station is manned by a master of their craft. Plastic chairs become portholes to skewers laden with charcoal grilled meat and bowlfuls of fragrant asam laksa, wafting tangy notes of tamarind, the broth waiting to be swiftly slurped up.

Finding a memorable meal in KL’s Chinatown is as easy as promenading down its central streets. A hot jumble of thick hokkien mee noodles have been a staple at Kim Lian Lee for decades, the once-upon-a-time stall now a two-storey tall institution. Just across the street is Koon Kee, another neighbourhood stalwart serving up their popular wan tan mee, char siu pork-topped Cantonese noodles tossed in a sweet black sauce, served with pork and shrimp dumplings. And just down Madras Lane (the street’s name has officially been changed, but locals still use its original title) lies a long line for yong tau foo, tofu typically stuffed with minced pork and fish paste, which has had customers queuing up for over 60 years. The catch? In this hubbub, it is all too easy to miss some of the less central but equally important eateries.

This storied assortment of kopitiams (coffee shops), family restaurants, and outdoor stalls from the halcyon days of Chinese culinary influence in Kuala Lumpur are tucked away from the bustle, a few even mapped outside of the boundaries of Chinatown. So if your palate craves a bit of the past in the present, weave in and out of Chinatown and explore restaurants where the same dishes have been served up for decades, for very good reasons.

1. Sang Kee

Est. 1970s

Address: 5A, Jalan Yap Ah Loy, City Centre

At dinner time Chinatown’s sidewalks (top) turn into a menagerie of meals. Chef Won San (bottom) gets to work on an order of freshwater prawn noodles. Photo by: Julian Manning

Sang har mee, or freshwater prawn noodles, are quite the treat in KL. The best sang har mee places are typically stalls, yet they do not come cheap, the most popular joints serving up the dish from anywhere between RM50-90/Rs835-1,500. Even though the portions are usually enough to fill two people, for those kind of prices you want to be sure you’re indulging in the best sang har mee in the neighbourhood.

Tucked in a discreet alleyway in the shade of pre-World War II buildings, on a little lane where late night courtesans would once congregate, lies Sang Kee. For over four decades this open air kitchen has been serving up some of the best freshwater prawn noodles in KL.

Those interested in a performance can inch up in front of the old man behind the wok and watch him work his wizardry, he doesn’t mind. Two beautifully big freshwater prawns are butterflied and cooked in prawn roe gravy, stirred in with egg, slivers of ginger, and leafy greens. Wong San, the chef, understands his wok like Skywalker understands the force—meaning, the wok hei (wok heat or temperature) is on point.

Once on your plate, plucking a plump piece of prawn out of the open shell is an easy feat. The fresh and supple meat is charged with the gravy, bite into it, and a flash flood of flavour courses out. In KL most versions of sang har mee sport crisp, uncooked yee mee noodles, which are then drenched in the prawn-imbued sauce. A lot of people love ’em this way, but I personally feel this gives the noodles the texture of a wet bird’s nest. Sang Kee’s noodles are cut thick, boiled, and then stir-fried, coated with oodles of scrambled egg, a style that lets the prawn’s flavours permeate every bit of the dish. At Sang Kee, for most folks a single p

ortion is enough for two at RM65/Rs1,085 a plate, but if that’s too steep a price, you can get the dish made with regular prawns for significantly less.

2. Soong Kee Beef Noodles

Est. 1945

Address: 86, Jalan Tun H S Lee, City Centre

The fine people at Soong Kee have been serving up beef noodles since World War II, and the product speaks for itself. It’s always crowded at lunchtime, but don’t worry about waiting around too long. Usually a server will squeeze you in at one of the many large round tables with plenty of neighbours who don’t mind the company. I love this approach because it means you get a good look at what your table-mates are munching on. That being said, newcomers should inaugurate their Soong Kee experience with beef ball soup and beef mince noodles—simple but hearty dishes that will give you a good idea of why the place has stuck around (small bowl of noodles from RM7/Rs120).

3. Sek Yuen

Est.1948

Address: 315, Jalan Pudu, Pudu

Mealtimes beckon travellers to dig into bowlfuls of beef ball soup (bottom left), pluck of piping hot scallop dumplings (middle left), and perhaps chow down on a myriad of meat skewers (top right). For dessert, munch on crunchy ham chim peng (bottom right), delicious doughnuts filled with red bean paste. If the flavour is too earthy for you, just pick up an entire bag of regular doughnuts (top left) or roasted chestnuts (middle right) from one of the city’s many street vendors. Photos by: Julian Manning

Sek Yuen is made up of three separate sections, spread out over adjacent lots a few feet from each other. One is being renovated, another is the original 1948 location, and the last is the crowded AC section built in the 1970s. I wanted to eat in the original section, but by the time I arrived the service was slowing down and everyone was dining in the AC section. When in doubt, follow the locals.

Two noteworthy staples of the restaurant, steam-tofu-and-fish-paste as well as the crab balls, were already sold out by the time I placed my order. So I happily went for the famous roast duck with some stir fried greens. The duck was delicious; the skin extra crispy from being air-dried, yet the meat was juicy with hints of star anise, which paired well with the house sour plum sauce. But what I enjoyed most was the people-watching. A Cantonese rendition of “Happy Birthday” played non-stop on the restaurant’s sound system for the entire 50 minutes I was there. The soundtrack lent extra character to the packed house of local Chinese diners, most of them regulars. To my right, a group of rosy-cheeked businessmen decimated a bottle of 12-year Glenlivet, and were perhaps the most jovial chaps I’ve ever seen. In front of me, a group of aunties were in party mode, laughing the night away with unbridled cackles. Perhaps the most entertaining guest was the worried mother who kept scurrying over to the front door, pulling the curtains aside to check if her sons were outside smoking. The sensory overload hit the spot. You could tell people were comfortable here, like it was a second home—letting loose in unison, reliving old memories while creating new ones.

I learned that when all sections of the restaurant are operational, Sek Yuen is said to employ around 100 people, many of whom have stuck with the restaurant for a very long time, just like the wood fire stoves that still burn in the kitchen (duck from RM30/Rs500).

4. Ho Kow Hainan Kopitiam

Est.1956

Address: 1, Jalan Balai Polis, City Centre

Although it has shifted from Lorong Panggung to the quieter Jalan Balai Polis, Ho Kow Kopitiam remains outrageously popular. Customers are for the most part locals and Asian tourists, unwilling to leave the queue even when the wait extends past an hour. In fact, there is a machine that manages the number system of the queue, albeit with the help of a frazzled young man whose sole job is telling hungry people they’ll have to wait a long time before they get any food. It’s safe to say the gent needs a raise. If you haven’t guessed already, get there early, before they open at 7:30 a.m.—otherwise you’ll be peering through the entrance watching the best dishes get sold out.

Many tables had the champeng (an iced mix of coffee and tea), but I’m a sucker for the hot kopi (coffee) with a bit of kaya toast, airy white toast slathered with coconut egg jam and butter; treats good enough to take my mind off of waiting for an hour on my feet. I then dove into the dim sum, and became rather taken by the fungus and scallop dumplings. The curry mee, whether it is chicken or prawn, was a very popular option as well. When it comes to dessert, the dubiously-named black gluttonous rice soup sells out fast, which devastated the people I was sharing my table with.

They also serve an assortment of kuih for dessert, including my personal favourite, the kuih talam. It is a gelatinous square made up of two layers—one green, one white. They share the same base, a mixture of rice flour, green pea flower, and tapioca flour. The green layer is coloured and flavoured by the juice of pandan leaves, and the white one with coconut milk. For someone like myself, who doesn’t have a big sweet tooth, the savoury punch, balanced by a cool, refreshing finish make this dessert a quick favourite (kaya toast and coffee for RM5.9/Rs100).

5. Kafe Old China

Est. 1920s

Address: 11, Jalan Balai Polis, City Centre