#Homai Vyarawalla

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

𝚠𝚘𝚖𝚎𝚗 𝚒𝚗 𝚙𝚑𝚘𝚝𝚘𝚐𝚛𝚊𝚙𝚑𝚢

Homai Vyarawalla.

#homai vyarawalla#women#feminism#women in art#art#feminismo#retro#aesthetic#woman#photoshoot#photography#women directors

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

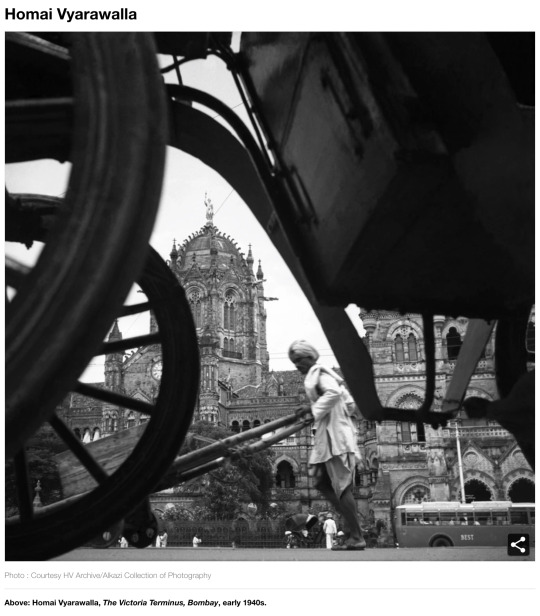

Homai Vyarawalla (Indian, 1913-2012) The Victoria Terminus, Bombay early 1940s, printed later Inkjet print 11 9/16 × 11 13/16 in. (29.3 × 30cm) Homai Vyarawalla Archive / The Alkazi Collection of Photography

Homai Vyarawalla (9 December 1913 – 15 January 2012), commonly known by her pseudonym Dalda 13, was India's first woman photojournalist. She began her career in 1938 working for the Bombay Chronicle, capturing images of daily life in the city. via Wikipedia

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Homai Vyarawalla: The trailblazer who became India's first woman photojournalist

Born in 1931, Homai Vyarawalla was India's first woman photojournalist – documenting India's transition from a British colony to a newly independent nation. BBC News documents Homai's life through her rare photography collection.

0 notes

Photo

Homai Vyarawalla | Students at the Sir JJ School of the Arts, Bombay, Early 1940s.

#Homai Vyarawalla#Students at the Sir JJ School of the Arts#Bombay#Early 1940s#students#art students#India

351 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Students of the J.J School of Arts at a picnic, Bombay, 1937. This is one of Homai Vyarawalla’s earliest images published in the Bombay Chronicle. Courtesy the Homai Vyarawalla Archive / Alkazi Collection of Photography

300 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Victoria Yerminus, Bombay, Photo by Homai Vyarawalla, 1940s

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Victoria Terminus, Bombay, 1940s

Photo: Homai Vyarawalla (Indian, 1913-2012)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

The New Woman Behind the Camera The National Gallery of Art

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

‘Keep Fit’ Class at Lady Irwin College. (New Delhi, 1945-46.) #HomaiVyarawalla

Homai Vyarawalla (9 December 1913 – 15 January 2012), commonly known by her pseudonym Dalda 13, was India’s first woman photojournalist. She began work in the late 1930s and retired in the early 1970s. In 2011, she was awarded Padma Vibhushan, the second highest civilian award of the Republic of India. She was amongst the first women in India to join a mainstream publication when she joined The Illustrated Weekly of India.

The scholar and curator Sabeena Gadihoke has written extensively about Vyarawalla’s images and practice. She also curated the exhibition Inner and Outer Lives in 2015, at the Shridharani Gallery, Triveni Kala Sangam, which explored previously overlooked trajectories in Vyarawalla’s oeuvre. In her curatorial text for this exhibition, she writes that Vyarawalla's photographs,

“(Homai's photographs) also bear testimony to how modernity was being defined for the young collegiate woman in India... While Vyarawalla’s published features draw attention to the ways in which bodies were imaged and shaped at these institutions, the exhibition focuses on what the young photographer seemed to catalyze by her presence among her peers in Bombay and Delhi.”

While some of these pictures of her peers in the institutions are poised and carefully staged to present idealistic images of femininity, grace and propriety; others are more intimate, playful and performative. These mirthful images of young women and their fleeting moments of leisure can be read as a tribute to friendship. They also challenge the often restrictive idea of the modern Indian girl in the late 1930s and ’40s.

Source: https://www.asapconnect.in/post/59/singlestories/the-first-women-of-the-institution

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women in photography

In 1955, the Museum of Modern Art put on what may very well be the most famous photography survey of all time, “The Family of Man.” It assembled a who’s who of 20th century talents—Henri Cartier-Bresson, Roy DeCarava, Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, Garry Winogrand, and August Sander. The show’s demographics, however, left something to be desired: of the 251 artists included, fewer than 40 were women.

A new show opening today at the Metropolitan Museum of Art continues recent efforts to reinsert women into the history of photography. Organized by Andrea Nelson and Mia Fineman with Virginia McBride, “The New Woman Behind the Camera” features 120 women photographers working during the 20th century. Its focus is not only Western artists who are already well-known, such as Dorothea Lange and Claude Cahun, but also under-recognized artists from other parts of the world whose work has been influential.

Below, a look at five under-recognized artists included in the Met show, which is slated to travel to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. after its run in New York.

When Consuelo Kanaga died in 1978, the New York Times called her “one of the foremost women photographers of her time.” By 1993, however, when the Brooklyn Museum devoted a retrospective to her, Kanaga’s reputation had faded to a point where curator Barbara Head Millstein took to the Times’ Opinions page to write that “her transcendent images have never received the acclaim they deserve.” Even today, Kanaga is nowhere as near as famous as some of the artists she counted as friends, among them Imogen Cunningham, Alfred Stieglitz, and Tina Modotti. This is due partly to Kanaga’s disposition—she wasn’t one for self-promotion—and partly to the nature of her work: her understated portraits of Black Americans did little to announce themselves as the great, empathetic images that they are.Kanaga took up photography at a time when its artistic merits were still subject to debate. At age 21, she began writing for the San Francisco Chronicle, spending time in the paper’s photo department, where she learned darkroom techniques. In 1932, she fell in with a circle of Bay Area photographers known as Group f/64, whose members included Cunningham, Ansel Adams, and Dorothea Lange. While not officially a part of the group, Kanaga, like its other members, was interested in a kind of photography that celebrated quotidian moments and everyday people—a sharp departure from the day’s reigning style, Pictorialism, which prioritized rigorous compositions over documents of everyday life.In the years that followed, Kanaga began creating her signature portraits of Black sitters—an unusual move at the time for a white photographer. She Is a Tree of Life to Them (1950), her most famous work, features a Black mother with her two children pictured against a concrete wall. (It was featured in Edward Steichen’s famed 1954 MoMA show “The Family of Man.”) The photograph exemplifies Kanaga’s approach, highlighting her subjects’ piercing gazes and using light in subtle elegant ways. It was the inner lives of her subjects that Kanaga sought to capture. “Most people try to be striking to catch the eye,” she once said. “I think the thing is not to catch the eye but catch the spirit.”

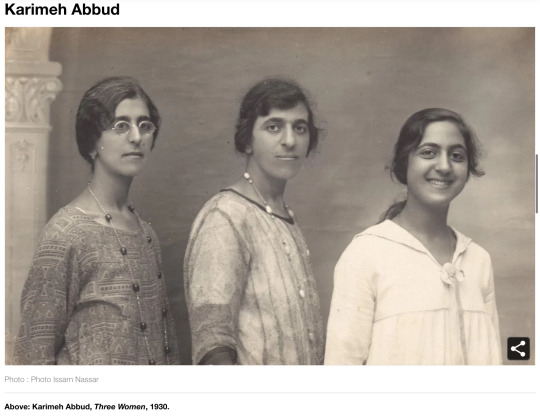

To an untrained eye, Karimeh Abbud’s photographs may not have read as art—and in fact, they were often made for commercial purposes first. But, with her studio portraiture, the Palestinian photographer charted a path that others have followed in the decades since she died in 1940.For historians, her work remains important because it marks a milestone: Abbud is believed to be the first woman photographer in Palestine, and possibly even one of the first woman photographers in the Arabic world. Yet her work remains little-known, and it did not even become the subject of a museum exhibition until 2017, when Darat al Funun, an art space in Ammann, Jordan, staged a survey based on works from the collection of Ahmad Mrowat, a major collector of Abbud’s work.Born in Bethlehem in 1893, Abbud became a photographer in the 1920s, turning her lens on the women and children around her. Later on, she would go on to open studios in various locations, including Jerusalem and Nazareth, and create portraits that pictured her sitters as they were. In a decisive break from the ethnological portraiture by Europeans that had long been dominant in the region, Abbud created images “of normality, of people appearing at their best, but within a middle-class context,” as scholar Issam Nassar has written. She chose not to hide her gender, and she even advertised herself as a “Lady Photographer.”

Homai Vyarawalla, India’s first female photojournalist, often took a matter-of-fact approach to her work: asked why she took up photography, she’d say, “It was just a job.” Yet the stunning pictures she took of India during a transitional period in the middle of the 20th century make it hard to imagine she didn’t have a more poetic intent.With her striking shots, Vyarawalla bore witness to the leadership of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, whom she befriended after he noticed her taking pictures, and the activism of Mahatma Gandhi. Anytime there was an important event taking place in the country, she could be found on the scene, often wearing a sari or a salwar (she declined to dress in Western garb as an assertion of her Indian national identity). In the process, she became widely known in India and respected as one of the great recorders of the country’s history.At the start of her career, though, her name was hardly known. This was, in part, because she was publishing photos under the name of her husband, Manekshaw Jamshetji Vyarawalla. Gradually, she began demanding recognition for her work, and when she got a job with the British Information Service in the ’40s, she demanded payment of a rupee per shot. In the years leading up to Vyarawalla’s death in 2012, filmmaker Sabeena Gadihoke helped revive interest in her work.

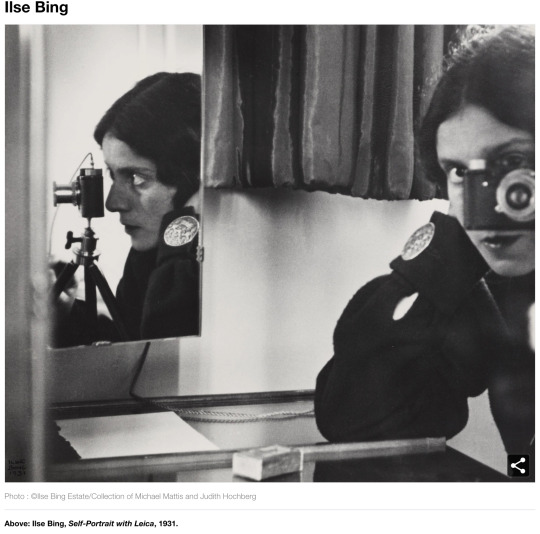

Once dubbed the “Queen of Leica,” Ilse Bing was one of the top photographers working in Europe during the pre–World War II era. She got that nickname from the tiny Leica camera she toted around with her, which she used to capture off-kilter images of modernity that often emphasize diagonal compositions. Through her lens, puddles on city streets, shadows thrown across ledges, and crowds traversing plazas become bracing visions of modernity’s changes to society, and its fast pace.

Bing initially intended to become an art historian, and her first photographic forays were done as part of her doctoral thesis during the ’20s. After Mart Stam, an architect aligned with the Neue Sachlichkeit movement in Germany, hired Bing to document his angular creations, she fell in with a circle of avant-garde artists in Frankfurt. She relocated to Paris in 1930 and rose to fame, getting commercial commissions from Harper’s Bazaar and fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli.

In 1940, Bing and her husband, both of whom were Jewish, were expelled from occupied Paris and interned for nine months. With the help of a fashion editor at Harper’s Bazaar, they both got visas and ended up in New York, where Bing remained for much of her career. Her work was fundamentally altered by the trauma of World War II, and in the ’50s, she gave up photography altogether. Her focus instead became poetry, which she considered “snapshots without a camera.”

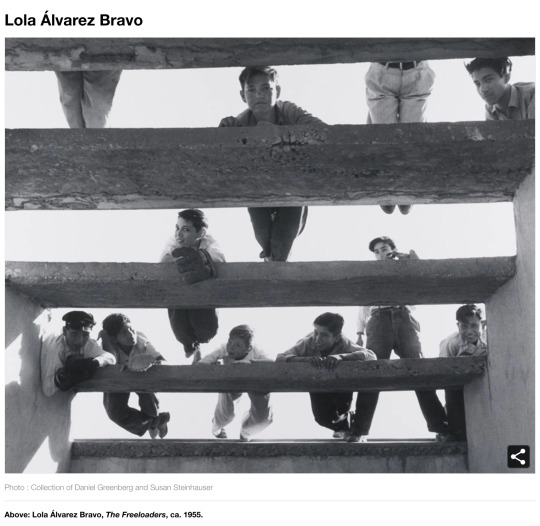

A modernist photographer whose output spanned photojournalism and more experimental work, Lola Álvarez Bravo once said that with her dynamic black-and-white pictures, she aimed to showcase “the life I found before me.” And what a life that was. Her images of Mexico, where she was born and based, are not simply documents, but something more—expressive renderings of people and the places they inhabit, filled with dramatic shadows and sharp diagonals that jut across her images. Occasionally, they also had an overt political context, such as in her images of Indigenous and poor Mexicans.

Within the U.S., Álvarez Bravo has been less celebrated than her onetime husband Manuel, who was also a photographer. (The two separated in 1934 and divorced in 1949.) The two ran in the same avant-garde circles, which included Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Frida Kahlo (who memorably appeared before her camera a number of times). At the center of the art scene in Mexico in the first half of the 20th century, Álvarez Bravo’s work was well-known among her peers, and she even acted as a gallerist for some of them.

It wasn’t until the past two decades that U.S. scholars began to take stock of her work, however. After a previously unknown trove of her prints was discovered in 2007, there has been renewed attention paid to her photographs, in particular her images that border on abstraction. At a 2018–19 survey at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation in St. Louis, for example, there was a focus on works such as Sexo vegetal (Plant Sex, ca. 1948), in which a close-up shot of a maguey plant comes to appear like genitalia. Álvarez Bravo called non-commerical works such as these “mis fotos, mi arte.”

#Metropolitan Museum of Art#“The New Woman Behind the Camera”#Women in art#Consuelo Kanaga#Karimeh Abbud#Homai Vyarawalla#Ilse Bing#Lola Álvarez Bravo

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Homai Vyarawalla (December 9,1913 – January 15,2012)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Galina Zakharovna Sanko (1904-1981) - Soviet photojournalist.

Galina Sanko (Russian: Галина Захаровна Санько) (1904–1981) was a Soviet photographer who worked as a photojournalist and was one of only five women who served as a war photographer during World War II. She was one of the most noted Soviet photographers and known in the West, winning awards both at home and abroad.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Homai Vyarawalla: The trailblazer who became India's first woman photojournalist

Born in 1931, Homai Vyarawalla was India's first woman photojournalist – documenting India's transition from a British colony to a newly independent nation. BBC documents Homai's life through her rare photography collection.

0 notes

Photo

A student of the JJ School of the Arts, Bombay, early 1940s. Courtesy the Homai Vyarawalla Archive / Alkazi Collection of Photography

Homai Vyarawalla, commonly known by her pseudonym Dalda 13, was India's first woman photojournalist. She began her career in 1938 working for the Bombay Chronicle, capturing images of daily life in the city. Vyarawalla worked for the British Information Services from the 1940s until 1970 when she retired.

68 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Homai Vyarawalla | Rehana Mogul at a women’s picnic, Bombay, late 1930s

216 notes

·

View notes