#HistoricTragedy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

THE GREAT MOLASSES FLOOD 1919 The Great Molasses Flood (1919) The Great Molasses Flood (1919): In Boston, Massachusetts, a massive tank of molasses burst, sending a tidal wave of sticky syrup through the streets, resulting in 21 deaths and extensive property damage.

#MolassesDisaster#BostonTragedy#1919Flood#MolassesTidalWave#HistoricalDisaster#BostonHistory#MolassesFlood#TragicEvent#Remembering1919#BostonMolassesDisaster#IndustrialAccident#MolassesCatastrophe#1919Boston#MolassesTsunami#HistoricTragedy#BostonStrong#MolassesExplosion#Memorializing1919#IndustrialHistory

1 note

·

View note

Text

My ships as Teny Toons

Please be respectful cause I respect your ships and I'm very willing to draw them if you ask

Ship list

Fruitcake (Sprout x Cosmo)

Cleancup (Tisha x Teagen)

HauntedCasino (Gigi x Connie)

ComedicHistory (Shelly x Razzle)

Catfish (Scraps x Finn)

Bubbleparty (Poppy x Looey)

More ship names I came up with:

HistoricalDrama (RnD x Shelly)

Historictragedy (Shelly x Dazzle)

Paperjokes (the original name I had for Scraps x Finn)

#teny toons#dandys world#connie x gigi#gigi x connie#sprout x cosmo#cosmo x sprout#finn x scraps#scraps x finn#teagan x tisha#tisha x teagan#shelly x razzle#razzle x shelly#poppy x looey#looey x poppy#digital art#art

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wrecked and Remembered: Two Canadian Catastrophes and their Stories in Stone

The natural beauty of Canada can seem almost unreal. Mountains meet glaciers and dense, sprawling forests while other areas look like epic desert landscapes. Intertwined with all the amazing rock and soil are Canada’s many stunning coastlines, rivers, and lakes. Canada has had an important connection with its bodies of water and waterways, relying on them throughout history to provide growth, food, and avenues for travel and commerce. Like many other regions deeply connected with their waters, there is always a chance for disaster when navigating the routes, carrying potentially dangerous cargo, and dealing with uncontrollable weather conditions. The coastlines of Canada are littered with shipwrecks, but some of these ships fell into circumstances that went far beyond unfortunate and resulted in utter disaster for those involved.

Located on a coastal road near the St. Lawrence River in Pointe-au-Père in Rimouski, Quebec, Canada is a tall stone structure inscribed with a grim tale of an excessive loss of life. The words are not alone in telling their tale; this monument is situated alongside a mass grave commemorating the spot where Canada experienced one of the greatest peacetime maritime disasters ever seen.

The RMS Empress of Ireland was a Scottish-built ocean liner measuring 570 feet long and had ninety-five voyages under her belt by May 1914. She was a relatively young ship, just under eight years old, with no reason to suspect that there was anything for any of her thousands of passengers to worry about.

On the morning of May 29th 1914 the Empress was setting out on her latest journey, traveling to Liverpool England from Quebec City, a routine trip headed by the newly promoted Captain Henry George Kendall who would be making his first venture up the St. Lawrence River. The passengers of the ship bid farewell to Quebec City, serenaded by the jovial sounds of the Salvation Army Band. The ship was manned by 420 crew members on hand to attend to the 1,057 passengers on board, some of which belonged to the higher classes of British, Canadian, Australian, and New Zealand society. The first-class passengers occupied cabins on the upper deck and lower promenade decks which encircled the ship. There were plants, a café, smoking room, a library, a string quartet, and a private dining area for the children of first-class passengers. Second class passengers traveled in the stern of the lower promenade and upper decks with a smoking room and access to the first-class café. The largest number of passengers on this voyage were traveling third class with cabins below decks with access to a section of the upper decks. They were all anticipating a comfortable and peaceful voyage to Liverpool.

A colorized image of the Empress of Ireland. Image via Wikimedia Creative Commons.

By 1:38am on the morning of May 29th the Empress had departed Pointe-au-Père and was making their way along their normal course. The conditions were clear when ship lights were first spotted approximately six miles from the Empress. The lights belonged to a Norwegian collier, SS Storstad, who also saw the Empress’s masthead lights off in the distance.

The clear conditions deteriorated extremely fast, enveloping the ships in a fog so dense that visibility was lost and the only indicator to the locations of the ships came from sounding their fog whistles. It was not enough. The next thing Captain Kendall saw were the lights of the Snorstad plowing out of the fog and heading directly for his ship.

At 1:55am the Snorstad made a direct hit onto the Empress at a 45 degree angle, slicing through the ship and sealing the fates of many. The situation escalated terrifyingly fast. Given the early morning hour most passengers were asleep in their cabins at the time of the collision and had no time to realize what was happening, let along scramble to the upper decks in hope of a lifeboat. Water poured into the ship, trapping and drowning those below deck. As the Empress listed sharply to its side water began pouring in through the open portholes. The ship was tilting over at such an extreme angle that even if anyone could get to the lifeboats, they could not be launched. Ten minutes after the collision the ship lay completely on her side in the water and only four minutes later the RMS Empress of Ireland sank beneath the river taking 1,012 of the 1,477 souls who had boarded the previous day. The death toll was even larger than that of the Titanic which had occurred two years earlier.

The SS Snorstad with damage sustained from the collison. Image via Wikipedia.org. Public Domain.

The wreck of the Empress came to rest only 130 feet below the surface and shortly after the disaster crews began diving in the search for bodies and valuables that had gone down with the ship. In 1964 a team of Canadian divers were able to recover a brass bell and due partially to the influx of divers the site of the wreck became protected under the Cultural Property Act in 1999 and was added to the Register of Historic Sites of Canada. While diving expeditions to the wreck are still carried out the dive has taken the lives of six more people since 2009.

The mass grave located at Pointe-au-Père was marked on the site several years after the disaster by the Canadian Pacific Railway Company. Several other memorials have been established in the region with monuments in the Mount Herman Cemetery in Quebec, a memorial in Saint Germain Cemetery in Rimouski, and a monument erected by the Salvation Army in the Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Toronto where an annual memorial service is held on the anniversary of the disaster next to their statue reading “In Sacred Memory of 167 Officers and Soldiers of the Salvation Army Promoted to Glory From the Empress of Ireland at Daybreak, Friday May 29, 1914".

Empress of Ireland Memorial. Image via Wikipedia Creative Commons.

The wreck of the RMS Empress of Ireland quickly faded from many minds with some saying it simply got overshadowed by pre-WWI tensions. Only three years later though Canada would suffer another horrific wreck with an impact that reached far beyond the ship itself.

The SS Mont Blanc was less than twenty-five years old on December 6th 1917. Measuring at 320 feet long, it was a steamship that transported general cargo to wherever the shipment was needed freeing it from standard schedules and a port of call. In November 1917 the ship was chartered to carry a cargo of miscellaneous munitions and explosives from New York to France and on December 1st the SS Mont Blanc departed for Halifax, Nova Scotia under the command of Captain Aime Le Medec.

The ship was very slow moving, and on December 5th it arrived in Halifax, intending to join a convoy of other ships gathered in the Bedford Basin before heading to Europe. But, the ship arrived too late to enter the harbor that evening and was forced to sit and wait with a cargo full of explosive TNT, picric acid, gun cotton, and barrels of high-octane benzol sitting on the deck. When it first arrived the ship was boarded by harbor pilot Francis Mackey who asked if they had and “special protections” or a guard ship to help guide them into the harbor given the extremely volatile cargo. They did not.

Early the next morning on December 6th 1917 the Mont Blanc began traveling through the strait that connects the upper portion of the Halifax Harbor to the Bedford Basin with its cargo of over 2,500 tons of explosive materials. Mackey was keeping an eye on the waters around them, but approximately ¾ of a mile out he caught sight of the SS Imo, a Norwegian ship with no cargo due to head back to New York. The Mont Blanc blew their whistle signaling the Imo, but the Imo simply responded with their own whistles, indicating they had no intention of changing their course. The Mont Blanc tried to shift, the ships cut their engines, but momentum carried them dangerously close to each other. The crew of the Mont Blanc knew they had to be extremely careful, their ship was essentially a massive floating bomb, something that no one on the Imo or anyone else gathering to watch the ships was aware of. After some maneuvering, the ships were nearly parallel, but then the Imo put their engines in reverse, sending them into the Mont Blanc’s starboard side.

Stern of Mont-Blanc before the explosion during a prewar visit to Halifax, Aug. 15, 1900. Image via Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, MP18.196.11, N-4,395.

The severity of the situation may not have been obvious at first. The two ships collided at extremely low speeds at approximately 8:45am, knocking over the barrels of benzol, and sending the fuel spilling onto the deck and flowing into the holds. At this point people on other ships were beginning to gather on their decks to watch. When the Imo disengaged from the Mont Blanc it caused sparks, igniting the fuel and starting a fire. The crew of the Mont Blanc knew they, and everyone around them, were in extreme danger. Captain Le Medec ordered his crew to abandon the ship and the fire quickly grew out of control. People were still watching from other ships, and now people living on the coast were coming out of their homes and staring out their windows at the inferno. They had no clue what was about to happen. The smoke and noise muffled anything the frantic crew of the Mont Blanc were screaming, and even if they could be heard no one understood the warnings being yelled in French.

The Mont-Blanc, now engulfed in flame, began to drift and it made its way to Pier 6, setting it ablaze, before finally grounding itself at the foot of Richmond Street. Then, in the blink of an eye, everything changed for the people of Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Just before 9:05am the fire reached the cargo hold and an explosion erupted in a blinding flash of white light. The shockwave ripped through Halifax, traveling more than 1,500 meters per second with the heat at the center of the blast reaching 5000C pushing a fireball of chemicals, debris, and shrapnel miles into the air and temporarily vaporizing the water around the ship. Soon after a tidal wave surged through Halifax bringing more devastation to the already nearly-leveled city. The Mont-Blanc itself was blasted into pieces and twisted parts of it would later be found miles from the site of the explosion. The Imo was lifted by the tidal wave and slammed into the shoreline. Halifax, a bustling city mere moments earlier, was hit by the largest man-made explosion in history before Hiroshima.

The SS Imo after being tossed by the tidal wave from the Mont Blanc explosion. Image via Wikipedia.org Public Domain.

The toll of the explosion was disastrous to Halifax with approximately 1,600 people losing their lives and another 9,000 sustaining injuries. More than 12,000 homes and buildings were damaged or completely leveled with the entire Richmond district laid to total waste. Structures were reduced to rubble and splintered wood, every window was shattered, every door ripped from their hinges, and rail cars and boats in the vicinity were simply crushed. Miraculously, all but one crew member of the Mont Blanc survived.

The devastation of Halifax after the Mont Blanc explosion. Image via Wikipedia. Public Domain.

Recovery efforts came in from hundreds of sources and six weeks after the explosion the Halifax Relief Commission was formed to take on the monumental task of managing and re-building Halifax with the North End being rebuilt as the Hydrostones, Canada’s first public housing project.

Halifax Exhibition Building in the aftermath of the explosion. Image via Wikipedia. Public Domain.

In 1966 the Halifax North Memorial Library was constructed with the first monument to the disaster, the Halifax Explosion Memorial Sculpture, placed in its entrance (the statue was later dismantled in 2004). Constructed in 1985, the Halifax Memorial Bell Tower stands today overlooking the site of the disaster and is the site for an annual remembrance ceremony that takes place every year on December 6th. It is the largest reminder among several still remaining in the Halifax region, with large pieces of the SS Mont-Blanc standing in Dartmouth and the clock tower of Halifax City Hall housing one clock on its north side permanently set at 9:05am to commemorate the minute that the city was nearly erased from the map.

Halifax Explosion Memorial Bell Tower. Image by Jesse David Hollington from Toronto, Canada - Halifax Explosion Memorial Bell Tower, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3670253

*************************************************

Sources:

Halifax Explosion https://www.britannica.com/event/Halifax-explosion

Explosion in The Narrows: The 1917 Halifax Harbour Explosion, Maritime Museum of the Atlantic https://maritimemuseum.novascotia.ca/what-see-do/halifax-explosion

The Great Halifax Explosion, History.com https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/the-great-halifax-explosion

Kiloton Killer The Collision of the SS Mont-Blanc and the Halifax Explosion https://sma.nasa.gov/docs/default-source/safety-messages/safetymessage-2013-01-07-ssmontblancandhalifaxexplosion.pdf?sfvrsn=d4ae1ef8_6

Two ships collided in Halifax Harbor. One of them was a floating, 3,000-ton bomb by Steve Hendrix washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2017/12/06/two-ships-collided-in-halifax-harbor-one-of-them-was-a-3000-ton-floating-bomb/

SS Mont-Blanc Explosion – 1917 https://devastatingdisasters.com/ss-mont-blanc-explosion-1917/

The Empress of Ireland, National Museums Liverpool https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/merseyside-maritime-museum/maritime-museum-floor-plan/lifelines-gallery/empress-of-ireland

On this day: The Empress of Ireland, 'Canada's Titanic,' sinks in 1914 by Kayla Hertz https://www.irishcentral.com/roots/history/empress-of-ireland-sinking

RMS Empress of Ireland https://www.shipwreckworld.com/maps/rms-empress-of-ireland

#HushedUpHistory#featured articles#Canada#CanadianHistory#MaritimeHistory#MaritimeDisasters#disasters#Halifax#HalifaxHistory#MontBlanc#Imo#EmpressofIreland#Snorstad#shipwreck#tragic#tragichistory#weirdhistory#forgottenhistory#strangehistory#historictragedy#Canadiandisaster#historyclass#historyisnotboring#sadhistory#truthisstrangerthanfiction#horror#historic#tragedy#memorialsites#CanadasTitanic

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

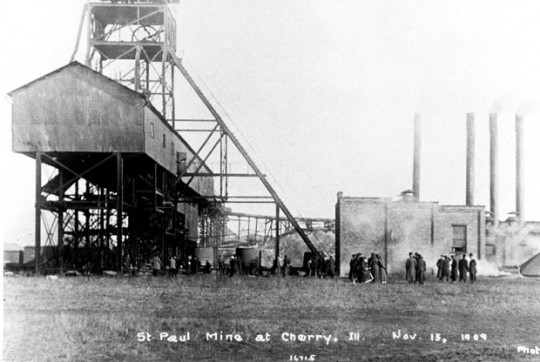

Deep Trouble: The Misfortune and Miracle of the Cherry Mine Disaster

As the Industrial Revolution arrived in the United States the idea of work greatly moved from the fields above to the depths of the earth below. Many facets of the new industries needed energy, and one source of that energy was coal. Buried deep underground, the process of harvesting this new essential crop was filthy, hot, dry, wet, backbreaking, and extremely dangerous. Workforces pushed for more and more coal and coal miners were not paid by the hour, but by how much coal they extracted from the earth. The hours were long and very often the blistered hands were young with entire families working in the mines in order to make as much money as possible.

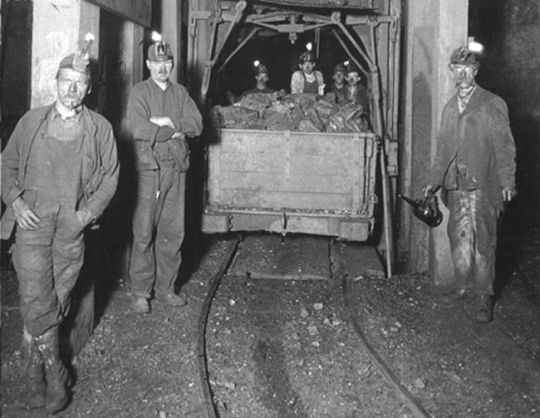

A typical mining scene from the early 1900s.

With cramped spaces, poor ventilation, wood and rope mechanisms, and light coming from lit candles, mines were prime environments for tragedy. When the St. Paul Coal Company opened their mine in Cherry, Illinois in 1905 it promised state-of-the-art safety measures including electrical lighting and a building with a large fan providing fresh air down below. These features were probably appealing to the workers, in the mines of northern Illinois alone approximately half a dozen miners were dying on the job every month. There was still a long list of dangers but the Cherry Mine was hugely profitable, producing around 300,000 tons of coal annually, and the mostly Italian immigrant workforce accepted the risks in pursuit of a better life outside the mine.

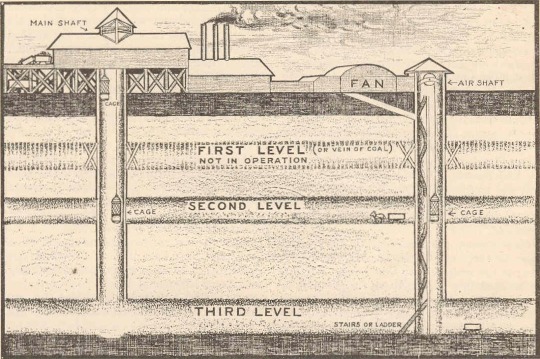

The construction of the Cherry Mine included three horizontal levels with two vertical shafts, a main and a secondary, going through them at approximately one hundred yards apart. Both shafts had wooden steps and ladders. The top of the main shaft had an eighty-five-foot-tall steel tower that controlled a mechanical cage used by the miners to travel up and down through the mine. At the top of the secondary shaft, which also served as an escape shaft, was the large industrial fan building that provided the luxury of fresh air to the workers.

Layout of the Cherry Mine.

On Saturday, November 13th, 1909 the nearly 500 employees of the Cherry Mine arrived at a work site that was slacking on some of its promises. Although it was fitted with electricity the mine had been without power for weeks forcing the miners to rely on flaming kerosene torches for light. The day was progressing as usual and the workers watched the noon hour arrive, bringing with it a small reprieve from the labor. When the workforce returned from their break none of the souls on site saw any indication of the terrible turn the day was about to take.

In addition to the human employees, the Cherry Mine also ran on the power of three dozen mules, all of which needed to be fed. Six bales of hay were loaded into a wagon to be lowered down to the animals and when the hay arrived at the second level it came into contact with one of the many kerosene torches providing the only light for the workers. But, the resulting fire was small, so small that a number of miners walked right past it in order to ride the 1:30pm cage up to the surface and there was initially no mention of it when they arrived above ground. As smoke began to build the miners began to take notice and attempted to put out the still considered minor blaze, but the smoke steadily thickened, and the situation began to reveal itself as urgent. The eventual solution was to drop the cage with the flaming hay down to the third level where there were water hoses used to wash the mules, but the cage got stuck. Eventually the contents of the fiery wagon was simply dumped down the shaft where it was easily extinguished. What the miners further down in the third level did not know was that as the hay traveled down it had ignited all the wooden support timbers on the second level and the air flow from the fan was quickly fanning the flames. The miners on the third level noticed their air quality diminishing and they called for a cage to be lowered but got no response. After climbing the ladder 165 feet up to the second level they were met with a horrifying sight, the cage station was left unmanned and the passageway was ablaze.

Photo taken on November 13th showing smoke rising from the mine.

It took forty-five minutes after the fire began for the evacuation call to be made. Cages full of men began racing to the surface while others scrambled up the ladders but the situation was dire for those working down on the third level. At approximately 2pm someone reversed the large industrial fan on the surface in an attempt to suck air out of the mine and minimize the fire, but it only made the situation worse turning the mine shafts into walls of flames and cutting off an escape route from the third level. When some of the miners from the third level reached the second level above them, they found the ladders to the surface burning due to the air and flames being sucked upward.

Cages were repeatedly lowered and brought up filled with dozens of panicked workers, many of whom owed their lives not to other miners, but to Cherry locals who ran to their aid. A group of approximately one dozen people including the mine manager, a local grocer, and a clothier all volunteered to go down into the mine in order to rescue some of the hundreds of workers that were still below and quickly succumbing to the lack of oxygen. The men made six successful trips down into the depths but on their seventh trip down the signals coming back up to the cage operator were jumbled and nonsensical, eventually stopping all together. When the operator brought the cage back up all twelve people inside had been burned to death from being lowered directly into the fire. When the fire department arrived on the scene they were forbidden to go down into the mines and their efforts were reduced to pouring water down into the burning mine shafts. At approximately 4pm the assumption was that they had done all they could and the shafts were closed. There were still 280 miners left underground.

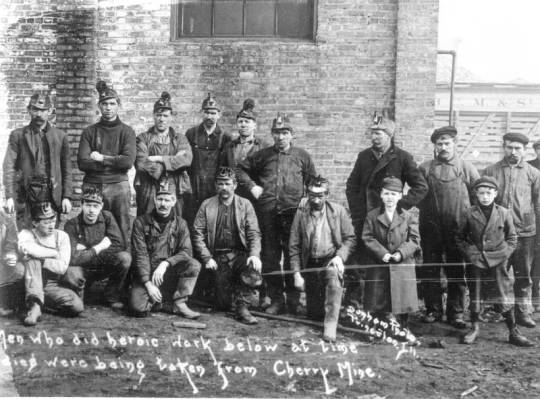

A group of miners who lost their lives in the Cherry Mine.

When Thomas White, Walter Waite, and George Eddy went to work on November 13th 1909 they had no idea what horror would befall hundreds of their coworkers that day. White and Waite were among a group of twenty-one laborers working in a secluded portion on the mine when Eddy, a mine examiner, informed them of the turmoil unfolding. The men rang for a cage to be lowered in order to escape but after getting no response they realized their unimaginable situation, they were left on their own inside the inferno.

The dangers of being left behind in the mine extended beyond the flames. Another killer lurking in the tunnels was Black Damp, a toxic mix of water vapor, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen that remains in the environment after oxygen has been depleted. The group of twenty-one miners attempted to find an escape route twice but both times they were beaten back by flames. Upon their third trip out into the darkness they encountered the dreaded Black Damp. This meant only one thing, the mines had been sealed and the oxygen was quickly fading away. With few options remaining the men collected themselves into a small, secluded area of the mine and began to build a wall of mud, rocks, and timbers to separate themselves from the fumes and flames. With only a few lanterns the men found themselves barricaded inside a small passage less than 500 feet long. All they could do was hope for a miracle.

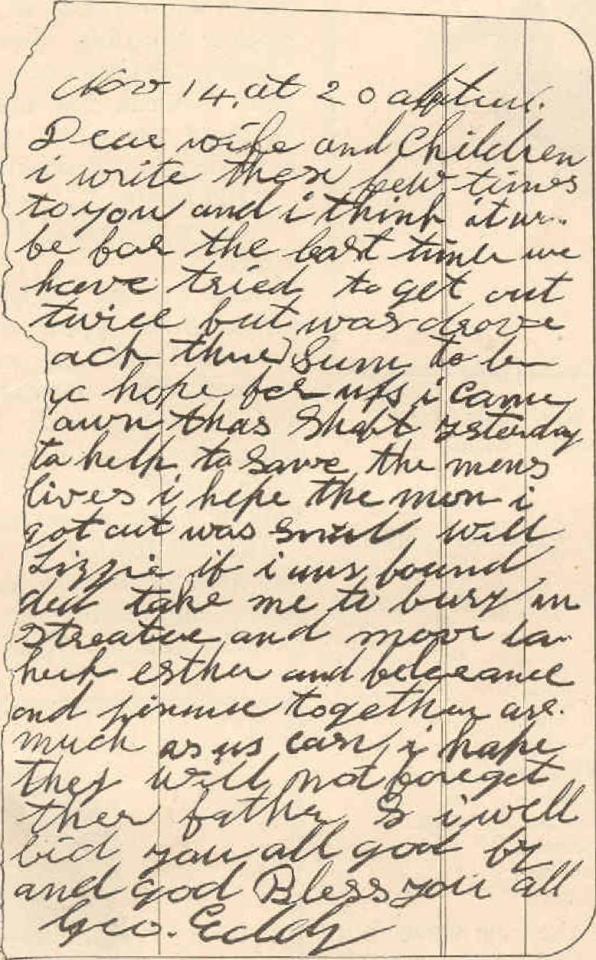

Every minute spent in the passage was agonizing. The men had no food and their only source of water was a small trickle that crept into their chamber and had to be collected, guarded, and rationed. In order to pass along both the time, and what they thought could be their final message to family, the miners wrote letters. One penned by Eddy reveals his opinion that survival was unlikely:

Dear wife and children: I write these few lines to you and I think it will be for the last time. I have tried to get out twice, but was driven back. There seems to be no hope for us. I came down this shaft yesterday to help to save the men's lives. I hope the men I got out were saved. Well. Lizzie, if I am found dead take me to bury me in Streator and move back. Keep Esther and Jenny and Clarence together as much as you can. I hope they will not forget their father, so I will bid you all good-by, and. God bless you all. George Eddy.

The letter written by George Eddy to his wife and children while he was trapped in the mine.

While the miners sat hundreds of feet under the surface they had no way of knowing what, if anything, was being done in order to save them. Meanwhile, in a terrible parallel, no one on the surface knew if there was anyone left down below to be saved.

Given the newness of the mining industry the processes of how to go about a recovery after disaster were still in their infancy. The day after the tragedy, on Sunday November 14th , rescue chief Robert Y. Williams of the United States Geologic Survey (USGS) and George S. Rice, Chief Mining Engineer at the Technologic Branch of the USGS, attempted to enter the mines but the still-blazing fires were too strong for the men to enter.

The Cherry Mine and volunteers the day after the fire.

On Wednesday November 17th there was a discussion between Rice and A J. Earling, President of the Chicago, Milwaukee, & St. Paul Railroad. Despite the odds, Rice still believed it was possible that there were survivors in the mine depending on how isolated they were when working in relation to the flames. Inspectors fought the notion of treating the proceedings as a rescue mission, in their minds too many had died in the blaze and twelve more had already died attempting rescues. In the end one investigator said that it was his belief that the USGS inspectors should continue their investigation and Williams descended into the mine.

The air was noticeably clearer.

Over the course of the next few days Rice and Williams went into the mine and upon finding that the air was free of toxic fumes state inspectors began the horrific task of collecting the dozens of bodies that never had the chance to return home.

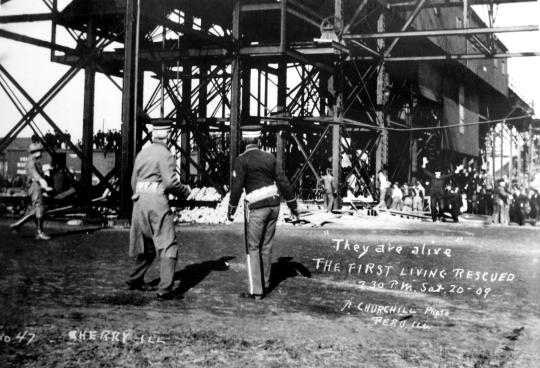

Saturday November 20th marked nearly one week after the Cherry Mine made the tragic turn from mine to morgue and for the twenty-one workers still trapped below time was running out. Some of the men spiraled into incoherent rambling, others crumbled in sheer weakness, and those who were still able to function knew there was nothing left to lose, they were going to break through the wall and go into the mine tunnels. Upon emerging from behind their handmade wall the healthiest of the men began moving outward in groups of four. To their relief and surprise they found that the air was no longer toxic, oxygen was back in the tunnels, which meant that someone had re-opened the mine shafts above.

After several hours of working through the tunnels a group of eight lost miners finally heard the sounds of salvation. Voices. A rescue party, led by Williams and Rice who pushed for rescue efforts in the days after the disaster, found the men and were quickly informed that there were more survivors that needed help. Rice was the only one on site who knew how to operate the apparatus needed to bring them all up to the surface. He trained volunteers how to use the device on the spot and by 1pm that afternoon the twenty-one miners were above ground, alive.

Image of the twenty-one miners being brought up alive.

To call Thomas White, Walter Waite, George Eddy, and their fellow workers lucky would be an understatement. The search continued but no other living miners were found. When the mine was finally closed for good the death toll stood at 259 lives lost leaving behind 160 widows and 390 children. Daniel Holafick, the oldest of the twenty-one trapped miners, was brought out unconscious and succumbed to breathing complications days after the rescue.

Investigation into the Cherry Mine disaster revealed a number of awful truths. The mine was called “the safest mine in the world” but the reality was that the construction and setup made it a deathtrap, especially for anyone working on the lowest third level. As stated by Rice privately “The escapeways were the most absurd arrangements that were ever conceived as far as concerns the third or lower vein.” It was also noted that the disaster could have been lessened, or potentially totally averted, if the mine was armed with basic firefighting equipment, fireproof materials in the mine shafts, and an escape route directly from the third level to the surface. Above all of this hung the fact that the mine was not being properly maintained and the reason the torches were there in the first place was because of a failure to fix the electrical system needed to supply light to the workers.

Worse than the revelations about building materials and lack of supplies was the discoveries about some of the people in the mine that awful day. It was determined that the Cherry Mine was illegally employing underage boys, at least nine that were under the age of sixteen, four of which were killed in the blaze. For this violation the St. Paul Mining Company was fined a total of $630 and they were further required to pay the families of the deceased $1,800 each.

The reaction to the disaster from the public was a mix of shock, heartbreak, anger, and disgust. Appalled at the low amount of money being given to widows and their families, private donations were gathered and distributed while a review board was established to hear the claims from families and survivors in need of help. The following year Illinois passed its first Workers Compensation Act ensuring that families and victims of an industrial accident would never again have to rely on private donations for support.

In hopes of preventing anything of this magnitude from happening again the Illinois legislature strengthened mine safety regulations requiring parts of mines to be fireproof, that mines be fitted with firefighting equipment, and the establishment of state firefighting and rescue stations. The disaster also led to significant changes in how the aftermath of mining disasters was considered. The rescue after the disaster in the Cherry Mine was the first successful rescue mission of its kind and it opened conversations about the importance of rescue work after mining disasters, the need for proper rescue equipment and training, and procedures to be followed by the miners should another similar disaster happen.

Months after the fire attempts were made to recover bodies and fragments of lives lost in the mine. Due to the heat and air quality, some bodies were mummified, others had letters in their pockets bidding their families goodbye, but many were never recovered at all.

Property of the miners recovered from the mine.

On May 15, 1971 the Illinois Department of Transportation and the Illinois State Historical Society dedicated a monument to the 259 lives lost in the Cherry Mine Disaster. A new monument was placed at Cherry Village Hall at the centennial of the disaster on November 14th 2009. Today the remains of some unidentified victims of the Cherry Mine Disaster lay in a mass grave alongside a memorial statue inside the Miner's Cemetery of Cherry, Illinois.

The Cherry Mine Disaster remains one of the deadliest mining disasters in American history.

Mass grave memorial stone placed for those lost in the Cherry Mine Disaster.

#HushedUpHistory#featuredarticles#history#mininghistory#industrialhistory#IllinoisHistory#Cherry#CherryMine#CherryMineDisaster#mining#mine#coal mining#coal#tragichistory#historictragedy#miningdisaster#disaster#fire#forgottenhistory#tragedy#Illinois#trapped#miracle#survival#rulechange#defiedtheodds#firehistory#historicfires#deadly#rip

0 notes