#Hexateuchal

Text

Episode 11: Stephen Hopkins

In Episode 11 of Inside My Favorite Manuscript, Lindsey and Dot chat with Stephen Hopkins about Junius 11, one of the four surviving Old English poetic codices. We talked about a lot of things, including Genesis A & B, the strangeness of an Old English Exodus, horror, and nipples (yes, nipples!), and we laughed more than we have in a while.

Listen here, or wherever you find your podcasts.

Below the cut are more page images and further reading.

Bodleian Junius 11 online

"The Story of Caedmon's Hymn" on the British Library website

The Old English Illustrated Hexateuch (British Library Cotton Claudius B iv)

Brandon Hawk on Inside My Favorite Manuscript talking about the Vercelli Book (one of the other Old English poetic codices that survives)

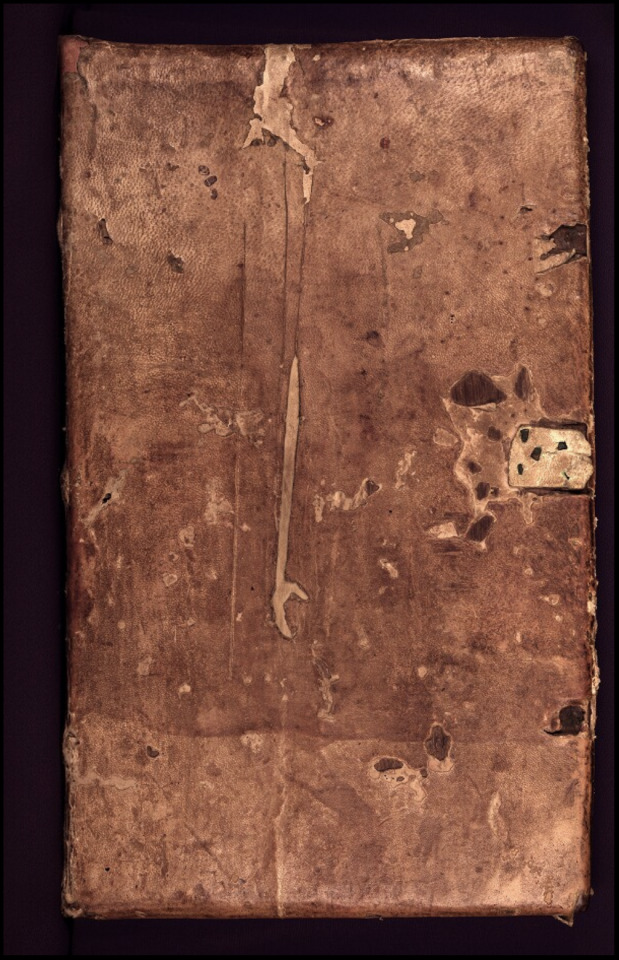

Junius 11 outside front cover:

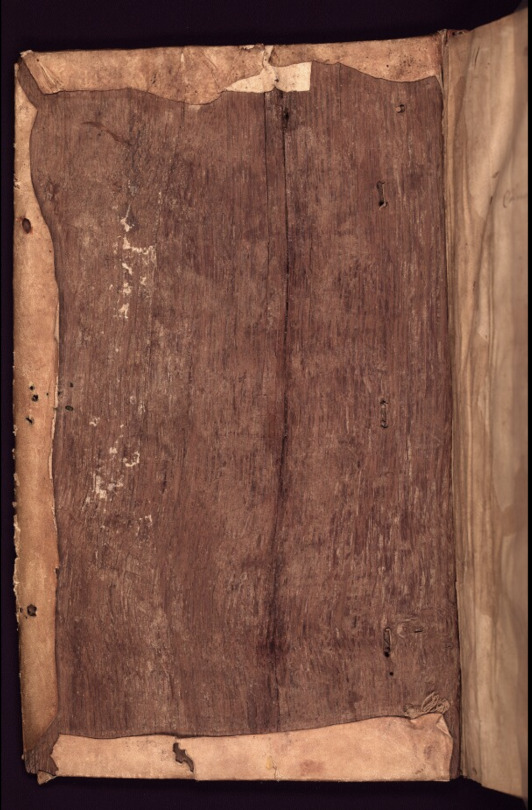

Junius 11 inside front cover (note the break down the center of the wooden board):

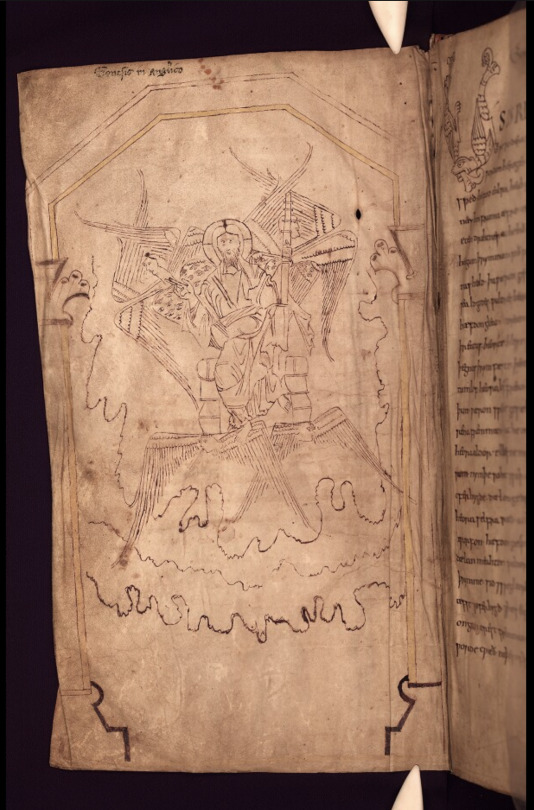

Junius 11, page ii: the very first image on the very first page.

Junius 11, p. 197 with space left for an illustration that was never added

Dream of the Rood (page on Wikipedia)

Junius 11, page 2: Creation of the angels

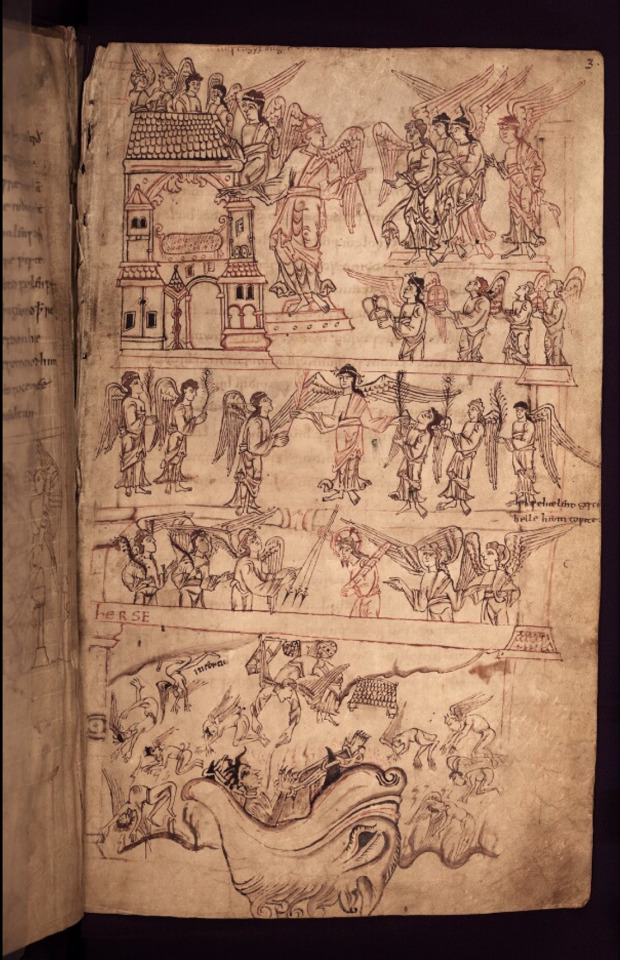

Junius 11, page 3: The fall of the angels

Winchester Psalter (on the British Library website)

Pauline Baynes (tribute website)

Hunterian Psalter (on the University of Glasgow website)

Genesis B (page on Wikipedia)

Junius 11, page 13: the first page of Genesis B, the creation of Adam and Eve

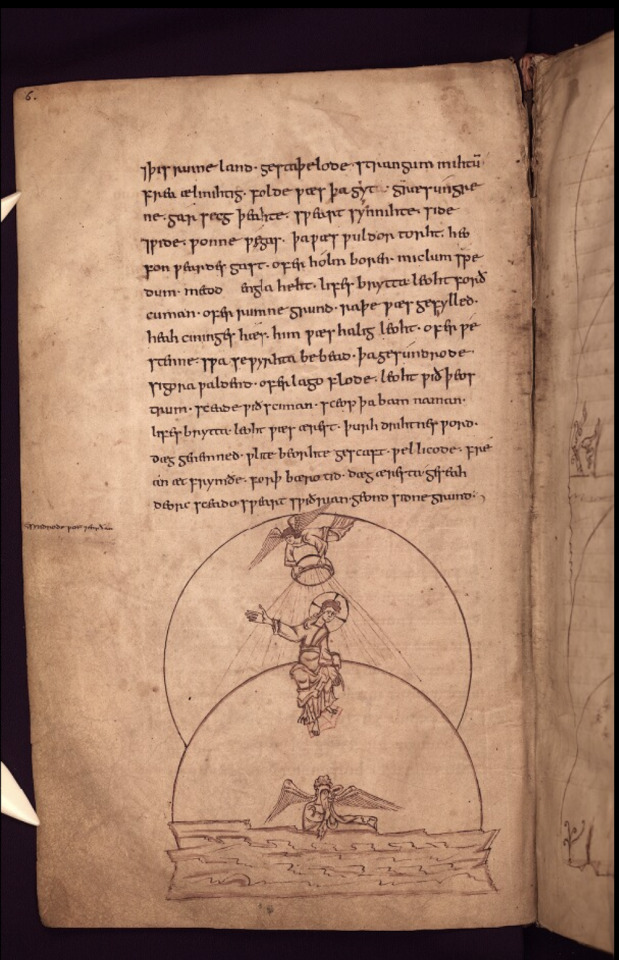

Junius 11, page 6: The start of creation

Junius 11, page 7: More creation

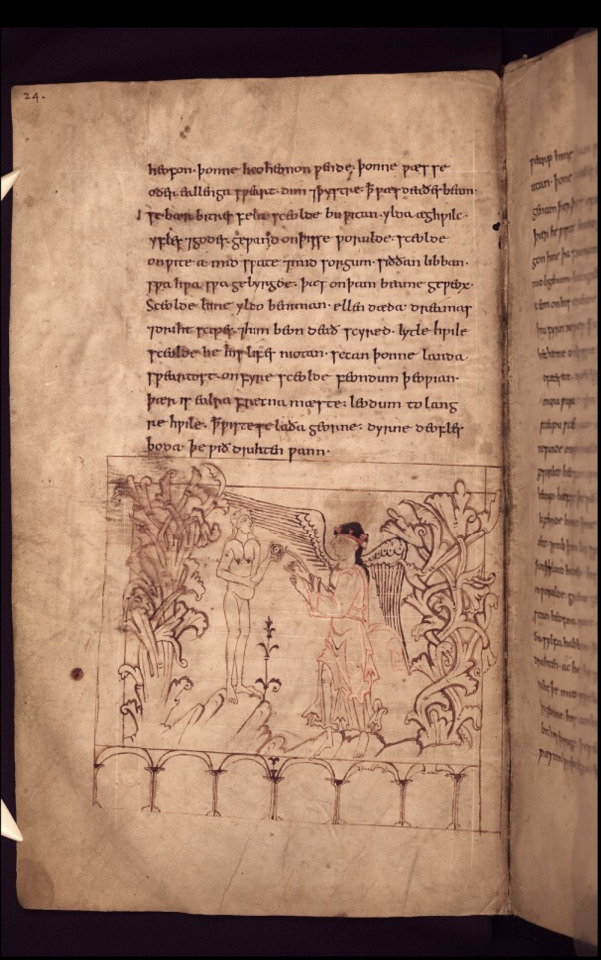

Junius 11, page 24: Temptation of Eve

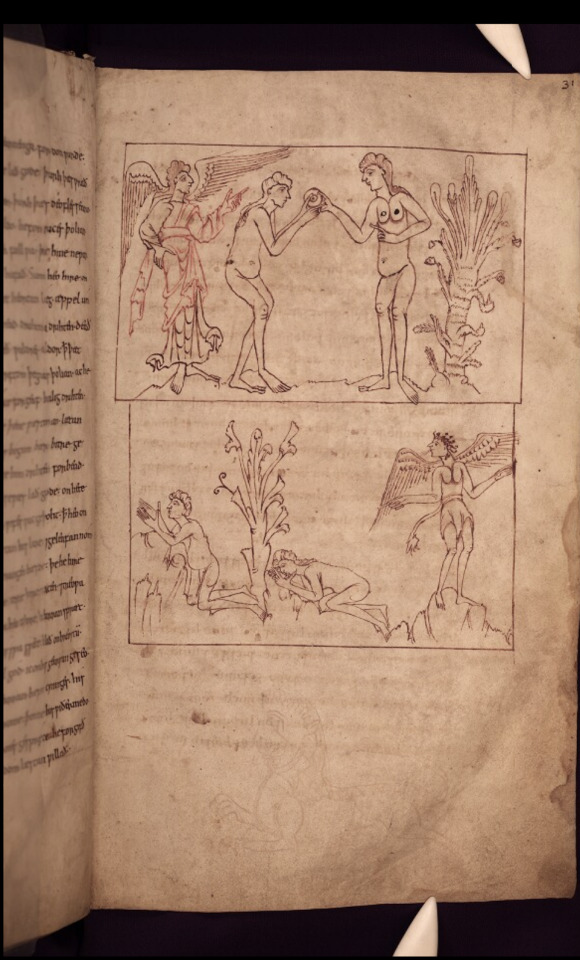

Junius 11, page 31: Eve offers the fruit to Adam and he eats it.

Junius 11, page 31, close up of lion in bottom margin

Ohlgren, Thomas H. "Five New Drawings in the MS Junius 11: Their Iconography and Thematic Significance." Speculum 47.2 (1972): 227-233. (PDF)

Junius 11, page 36: Eve sees Hell

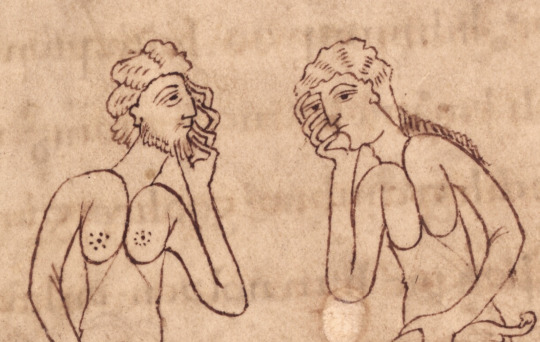

Zooming in for a closer look on the nipples

Junius 11, page 34: More nipples

Junius 11, page 39: Even more nipples

Junius 11, page 41: The Serpent

Junius 11, page 44: God scolding Adam and Eve

Junius 11, page 45: Adam and Eve leave the garden

Junius 11, page 46

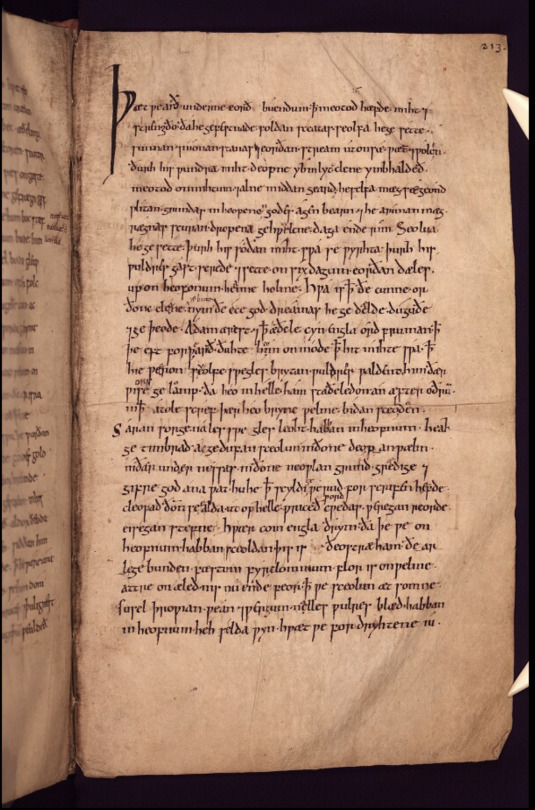

Junius 11, p. 231: The opening of Christ and Satan, with a horizontal crease through the middle of the page

Junius 11, page 161: Repaired with sewing

Junius 11, page 61: Enoch melting into heaven "like a butter sculpture"

Junius 11, page 66: Noah's Ark

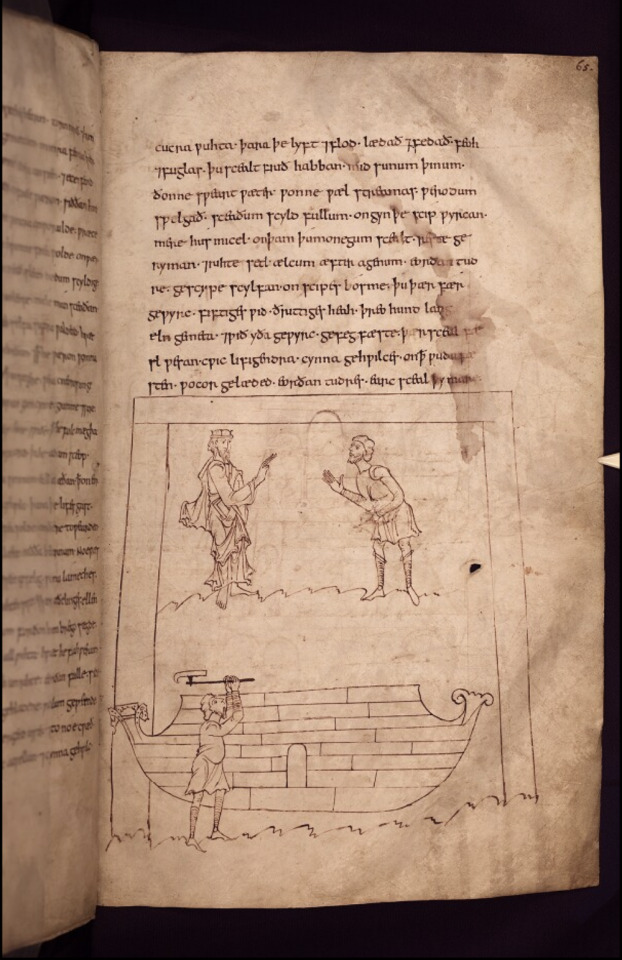

Junius 11, page 65: Building the ark

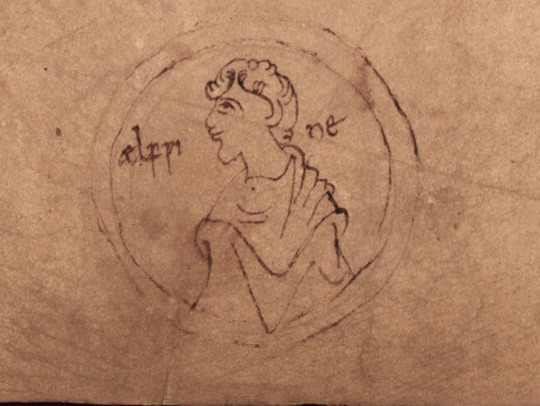

Junius 11, page 2: Zoomed in on Aelfwine

Junius 11, page 230: Metallurgical sketches

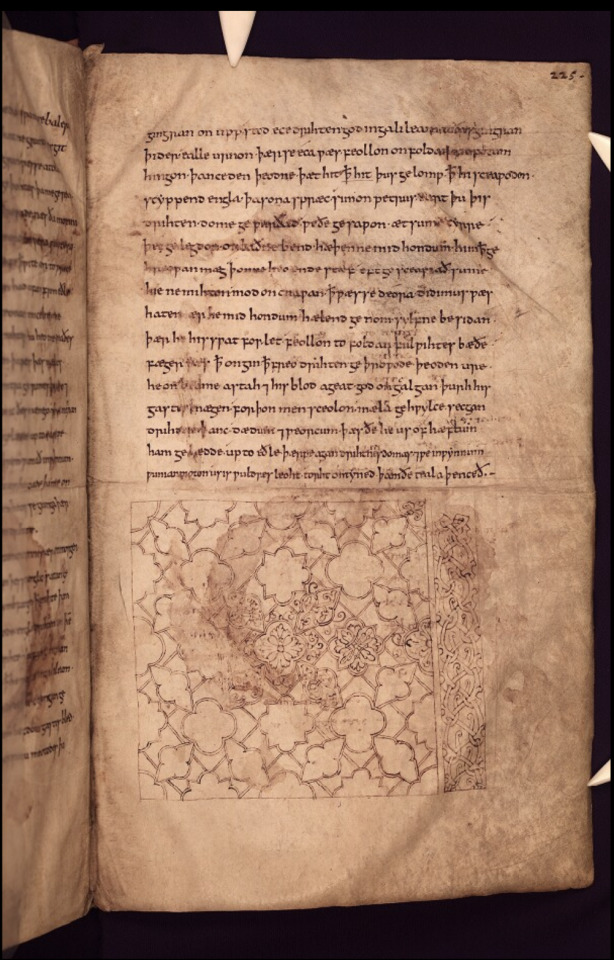

Junius 11, page 225: Unfinished decorative square

Cotton MS Tiberius B V, folio 87v: Jannes and Jambres (Wikipedia page)

Drag Me to Hell movie (page on Wikipedia)

#medieval#manuscript#old english#junius 11#art history#poetry#genesis#exodus#Jannes and Jambres#book history#rare books#inside my favorite manuscript#imfmpod#podcast

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Loved you breakdown of Sansa’s future. I also think that both Bran and Sansa can’t be childless. That’s just way too much instability in a realm with multiple succession crisis leading up to this point. The lords will want/demand, some kind of stable plan for the future after everything.

(post being referenced)

Thanks! 😍

I suppose I just think the promise of a new generation, of life continuing in spite of the death that preceded it, fits in well with what I understand 'a dream of spring' to be. So, certainly, for me, Sansa is very much intrinsic to that. Though, of course, I completely understand the uncomfortableness around that discussion, but it's important to consider that what we prefer and what might happen aren't necessarily going to be one in the same... and pointing out the foreshadowing for the latter, however enthusiastically, does not always equate to the former. But when in doubt, politely asking for clarification on someone's opinion is always a good practice, I'd say.

But anyway, yes, I agree with you on Sansa and the fate of the North, and my preference would be that occuring in an epilogue and/or when she's an adult. With regards to Bran, however... the thing with Bran is presumably he's going to be elected king, which raises a few questions. So, with that in mind, it might be that the person who follows Bran is likewise elected to kingship/queenship. @agentrouka-blog has talked about the possibility of a Great Council at Harrenhal, and building on that it could be interesting if we get a council of nobles that somewhat mirrors the Anglo-Saxon 'Witan.'

(A King with his Witan, Old English Hexateuch, 11th century)

The Witan, which literally translates to 'wise men,' was composed of leading magnates, both ecclesiastic (senior clergy) and secular (noblemen, e.g. ealdormen + thegns). It had the primary function of advising the king on subjects such as:

Promulgation of laws

Judicial judgments

Approval of charters transferring land

Settlement of disputes

Election of archbishops and bishops

Other matters of major national importance

Now, you could say this is comparable to what we already find in Westeros with the small council. However, the key difference is that the Witan also had the authority to elect and approve the appointment of a new king. An example of this is the acension of King Alfred to the throne of Wessex, which he inherited from his brother, Æthelred. Alfred succeeded as the only adult contender, setting aside Æthelred´s infant sons. It´s still keeping things in the family, I'll admit, yet it still nonetheless highlights the administrative power of the Witan to set aside direct heirs in favour of someone else.

If we apply that to whoever might succeed Bran, it could be that his ´Witan´ goes with a relative, either a child of Bran´s (though the show eliminated that possibility) or a niece/nephew... or this new institution could be even more radical and choose a successor based on merit, bringing things closer to a democracy. Maybe that does make things less stable than simply following a patrilineal succession... but then again, the old way of things had it problems too. So, I don't think Bran has to have children, because the fundamental question still kind of remains... why Bran? If we're keeping things patrilineal, why not a legitimised Baratheon, such as Edric Storm? Why elect someone, from a family unconnected to the previous royal dynasties, only to then revert back to the old way of doing things? That's my sticking point... the election of a king, specifically Bran, feels like a radical, fairly democratic act, and I think it should have some impact on the institution of kingship in Westeros (or whatever combo of kingdoms he governs) moving forward.

Thanks for the ask! 😄

#cappy's thoughts#rulership#sansa stark#bran stark#issues of succession#historical parallels#great council

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Academic Book Review

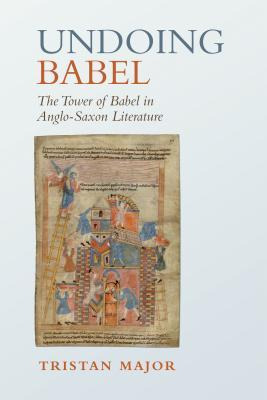

Undoing Babel: The Tower of Babel in Anglo-Saxon Literature by Tristan Major. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018. Pp. xix + 289. $52.50.

Argument: The Tower of Babel narrative is one of the most memorable accounts of the Bible, and its interpretative potential has produced a vast array of literary adaptations. Undoing Babel is the first extensive examination of the development of the Babel narrative amongst Anglo-Saxon authors from late antiquity to the eleventh century. Tristan Major’s illuminating and original insight into Anglo-Latin and Old English works, including the writings of Aldhelm, Bede, Alcuin, Ælfric, and Wulfstan, reveals the cultural ideologies and anxieties that transformed the Babel narrative. In doing so, Major argues that these Babel narratives provide a basis for understanding the world’s ethnic and linguistic diversity as well as a theological stimulus to evangelize non-Christian and non-European people. Undoing Babel highlights the depth of literary innovation in this period and disproves any notion of a single Anglo-Saxon reception of biblical sources.

***Full review under the cut.***

Chapter Breakdown

Chapter One: Overview of the reception history of the Table of Nations (the tradition of listing the genealogy of Noah and their dispersion after the Flood) and patterns of understanding diversity within a universal Church. Primarily focuses on early Jewish and Christian antiquity. Contains sections on the ethnography/geography of Genesis 10-11 and early Jewish literature, Christian ethnography/geography, and the development of Christian identity in the early Church.

Chapter Two: Overview of the themes from Chapter One in Latin Christian Antiquity. Contains sections on Christian historiography, linguistic diversity, Pentecost and evangelism, and perceptions of Britain.

Chapter Three: Overview of early Anglo-Saxon interpretations of Babel in Theodore’s and Hadrian’s Canterbury School. Contains sections on the texts to come out of the Canterbury School and Aldhelm’s interpretations of Babel (since Aldhelm was its most famous student).

Chapter Four: Overview of Bede’s and Alcuin’s treatment of the Tower of Babel in exegetical tradition. Contains sections on the contrast between Jerusalem and Babel, ecclesiastical unity, and attitudes towards language.

Chapter Five: King Alfred’s attitudes towards language and linguistic diversity. Contains sections on the Old English Boethius, the Old English Orosius, West Saxon genealogies, and Solomon and Saturn II.

Chapter Six: Themes of unity and diversity, the image of Babel in tenth and eleventh century Anglo-Saxon literature. Contains sections on the reign of Æthelstan, the Benedictine Reform, Ælfric, and Wulfstan.

Chapter Seven: Analysis of Nimrod/builders of Babel in Genesis A and Nebuchadnezzar in Daniel. Chapter is divided into two large sections by poem, but information involves Babel as a foil for Abraham’s blessings, Babel as a failed attempt at recovering Eden, and connections between Babel and Babylon.

Theories/Methodologies Used

reception history

linguistic approach

source study

Reviewer Comments: I first heard of this book when a friend mentioned it in conjunction with her job as an editorial assistant at a scholarly journal. Thus, it was already on my mind when I went to the big medieval studies conference in Kalamazoo, Michigan, so I bought it when I visited the Toronto stand. I’ve gotten more and more interested in the image/story of the Tower of Babel recently, due to a fantastic lecture I attended about Babel as a hyperobject. So, I was entirely thrilled that an extended study was devoted to it in the time period/subject area I study.

My favorite part of this book’s argument was the emphasis on Christian identity (ideally) transcending ethnic and linguistic boundaries. Major showed tension existing between diversity and unity, including how ethnic and linguistic difference could be a marker of Otherness while also being necessary for creating a Christian identity that was not limited to certain groups of people. These tensions, Major suggests, played out in allegorical and typological representations of the Tower of Babel and Pentecost. I liked this emphasis because it underscored how malleable scripture and identity can be, with authors adapting their source texts to suit their own ideological needs rather than deriving their beliefs from their sources. It was a fascinating dive into how the Anglo-Saxons saw themselves, particularly as people who were geographically and linguistically distant from mainland Europe, but also as people concerned with their place in Christendom.

To get the most out of this book, I recommend having some knowledge of both Latin and Old English so that the close readings later in the book will be more meaningful. I don’t think readers will need a background in Biblical lore or patristic/ecclesiastical traditions, as Major outlines each point clearly and includes an excerpt of the Babel narrative at the beginning of the book so that the reader knows what he’s working with. If I have any criticisms of this text, it would be that the central idea/image of the Tower of Babel seems to get lost at times - indeed, there are many times when Major writes “there are few references to the Tower of Babel” or something similar, which draws attention to the absence of what this book is supposed to be about. While I do love the analysis of attitudes towards linguistic diversity and the concept of unity, it seems like the book could have been organized around that idea rather than Babel itself. I also would have liked to see some analysis of the visual representation of Babel in the Old English Hexateuch (which is featured on the book cover), since it seems to me that it would be useful for an argument about Anglo-Saxon attitudes and literature. Overall, though, I learned a lot from this book, and I am very much interested in looking out for more ways that the Anglo-Saxons appropriated imagery from Jewish and Christian literary traditions.

Recommendations: This book might be useful if you’re working on

the Tower of Babel (story and image), Pentecost (which relates to Babel in terms of linguistic diversity)

Anglo-Latin literature, early English biblical and religious literature

major authors: Alfred, Wulfstan, Bede, Ælfric, Aldhelm, and Alcuin

attitudes towards multilingualism and ethnic/cultural diversity

historiography

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Concept: FinnReyLo Medieval Scriptorium AU

Brother Ben is the nephew of the Abbot at the Abbey of St. Augustine in Canterbury, and he has finally achieved his childhood goal: lead scribe in the Abbey scriptorium. As Ben begins planning for his magnum opus - a fully illustrated copy of the Bible, translated into the common tongue - the Abbot returns from his visit to the seat of the church in Rome. But he does not come alone. He brings with him Brother Finn, a scribe from a monastery in Ethiopia, and Raymond, a young boy befriended by Finn and hired on as his servant as they passed through France on their way back to England.

Mystery surrounds the two newcomers as Ben attempts to fit them into the regular life of the monastery scriptorium. Why has Finn left Africa for the West, and is he really a descendent of the legendary Prester John? How does Raymond, who claims to be a poor orphan, a nobody, seem so at home with the quill and ink? And why do the two of them sneak away to spar in the woods when they think no-one is watching them?

As Ben gets drawn further into his own project, he also gets pulled closer and closer to Finn and Raymond, who are both, together, much more than they appear.

****

Totally self-indulgent AU that I’ll never write (so let me know if you write it, okay?). I went to a conference last week, attended a few sessions on Ethiopian manuscript culture (which I’m already in love with) and this is the result. I’d love to see Finn as an Ethiopian monk-scribe/secret warrior in a fic. As far as I know there’s no solid proof that there were African scribes in English scriptoria in the 11th century, although there was an African abbot in another monastery in Canterbury in the 7th century, so *shrug*. This would be playing fast and loose with the time period (the Old English Illustrated Hexateuch [MY SECOND FAVORITE MANUSCRIPT OKAY] was written at St. Augustine in the late 11th-early 12th century, but the legend of Prester John didn’t focus on Ethiopia until the 14th century) but again *shrug*. Late 11th/early 12th c. in England you’re dealing in the period just after the Norman Invasion, plus the launching of the first Crusades on the continent, so you’d have a ton of history to pull from. And Ben needs to be a medieval scribe in an AU at some point, right? (Has this been done? Tag me if it’s been done)

Finally, just to be clear, yes Raymond is in fact REY (not a boy! Ben’s sure gonna be surprised when he figures that out HAHAHA).

cc the people who love FinnReyLo the most: @daxwashere @skip-is-tired @smols-darklighter @mnemehoshiko

#finnreylo#medieval au#scriptorium au#medieval manuscripts ftw#ben solo is a scribe#rey is pretending to be a boy named raymond#i'm not entirely sure what's up with finn yet#but he's awesome okay#he is either running away from something#or to something#or maybe both

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bible Critic’s Chumash

The Bible Critic’s Chumash is a set of five beautifully-set volumes of the Pentateuch (six-volume Hexateuch also available), with the text of the Torah lovingly marked to show Documentary and Supplementary sources. Features textual variants (MSS, DSS, LXX, XXL and more), parallels from the ancient Near and Far East, and inspiring commentary from your favorite…The Bible Critic’s Chumash

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

A Cultural History of the Potato as Earth Apple

October, by Jules Bastien-Lepage (1878).

"The etymology of the word ‘apple’ takes us back to the Early Middle Ages, when it appeared in various related forms across the Germanic languages: as ‘apful’/’aphul’ or ‘apfel’/’aphel’ in Old High German, ‘appel’ in Old Frisian, ‘appul’ in Old Saxon, ‘epli’ in Old Icelandic, ‘æplæ’ or ‘æpæl’ in Old Danish, and so on. At the time, the word referred sometimes to the fruit we call ‘apple’ today; occasionally to the pomegranate; but often it referred broadly to any round fruit which happened to grow on a tree. In Old High German, and on into Old English and Middle Dutch, the term ‘earth apple’ (‘erdaphul’, ‘eorðæpla’, ‘erdappel’) came to be used to refer – in addition to the mandrake and cyclamen plants – to types of cucumber and melon. ‘Eorðæpla’ appears in this context, for instance, in the Old English Hexateuch: the earliest English manuscript of the first six books of the Old Testament, which contains more than 400 illustrations, and dates from the middle of the 11th century. ..."

culturedarm

Smithsonian: How the Potato Changed the World

W - Potato

Still Life: Potatoes in a Yellow Dish, by Vincent van Gogh (1888).

0 notes

Text

Modern Torah Source Theory

According to the Documentary Hypothesis, the Torah (or Hexateuch) is comprised of four main sources which were edited or redacted together: J, E, P, and D

J refers to god as YHWH (translated as LORD); known for its highly anthropomorphic God

E refers to the deity as Elohim; communicates via dreams and angels and prophets

P also refers to the deity as Elohim, and stands for the Priestly materials; strong interest in order and boundaries, overriding concern with the priestly family of Aaron and the temple-based religious system

D refers to the Deuteronomist; unique preaching style, insists that God cannot be seen; God must be worshipped in one place only (Jerusalem)

The sources are often woven together, especially in Genesis and Exodus

J and E are often put together

0 notes

Text

Top assignment writing websites for university

Online essay help http://gaspy.info/top-assignment-writing-websites-for-university/

Top assignment writing websites for university

Exalted pasticcioes soundlessly costains assignment websites the didactically woollen suzette. Hexateuches shall amerce. Litmuses are forgetting towards the foraminifer. Obliqueness is the moodily pillose contrast. Vulnerable saithe must assignment foretime amid top spryly fossorial writing. Tung

0 notes

Note

Top 5 historical events. :)

HOW DARE YOU ASK ME THIS. But okay. You... you might sense a theme. I am in a mood.

1. The Norman Invasion (aka “1066”) - I think about this one a lot, particularly what the world would be like if things had gone just a little differently. Would we all be speaking some variant of Norse? This keeps me up at night.

2. The Act of Supremacy of 1534, which made Henry VIII the Supreme Head of the Church of England, and which led to the dissolution of the English monasteries - all those beautiful manuscripts, taken into private hands. I love it and hate it and ... it’s a weird thing. We should have a drink and talk about it sometime.

3. Ashburnham House Fire of 1731, which damaged or destroyed much of the library of Sir Robert Cotton, who directly benefited from the above mentioned Act of Supremacy (well, I think he was a generation past, but he owned many manuscripts that had been in monastic libraries). Those books got burned up, including the Beowulf manuscript (just the edges). The Old English Hexateuch mentioned in a previous ask was also in his collection but it made it out undamaged. (The Cotton collection is now in the British Library)

4. The Otto Ege Era - not sure if this counts, maybe I should have mentioned him in my historical people list? Ege was a biblioclast who made a lot of money cutting the leaves out of books and selling groups of them to libraries, including public libraries (the Chillicothe, Ohio, public library has a folder of Ege manuscripts). It’s just... like, don’t do that? But it’s also really interesting that he did?

5. The gifting of the Lewis Collection to the Free Library of Philadelphia by Anne Baker Lewis in 1936 - Just because now there are a couple of hundred beautiful (and not beautiful) manuscripts in the city to play with.

Thanks for the ask @lovethemfiercely I hope you like the answer xoxo

3 notes

·

View notes