#Hepworth Gallery

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

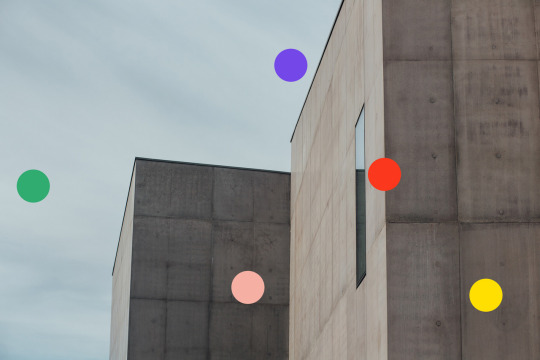

The Hepworth

#the hepworth#hepworth gallery#barbara hepworth#photography#architecture#concrete#graphic design#art direction#colour

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

#photography#photographer#yorkshire#clickasnap#travel#blogger#photo#River Calder#Hepworth#Hepworth Gallery#Wakefield

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wife imitates art

S.I. Twaddle, 2023

0 notes

Photo

Eileen Agar, Adam’s Apple, 1949, watercolor on paper The Hepworth Wakefield

532 notes

·

View notes

Text

one thing about me is i will stand for hours in an art gallery and draw a sculpture from 6 different angles and annoy all the elderly couples

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Went to see a great little exhibition of works by Barbara Hepworth, currently on view at the Piano Nobile gallery in Notting Hill. The focus is on her stringed sculptures, many of which are pretty cool. Entry is free and it's on until 6 May 2025.

315 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kim Lim: Space, Rhythm & Light, Edited by Abi Shapiro, Lund Humphries in association with The Hepworth Wakefield, London, 2023 [© Estate of Kim Lim / Turnbull Studio – Studio Kim Lim / DACS, London]

Cover Art: Kim Lim working on 'Twice', 1966 (or 1968) [WARE: Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions. © Estate of Kim Lim / Turnbull Studio / DACS. Photo: Jorge Lewinski. © The Lewinski Archive at Chatsworth / Bridgeman Images]

Exhibition: The Hepworth Wakefield, Gallery Walk, Wakefield, West Yorkshire, November 25, 2023 – 2 June 2024

#graphic design#art#sculpture#exhibition#catalogue#catalog#cover#kim lim#studio kim lim#turnbull studio#jorge lewinski#the hepworth wakefield#lund humphries#2020s

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

You occasionally get a shocked or surprised reaction to having revered paintings, sculptures or great works of art in places like hull cos there's this accepted notion that the megatropolis cities like Manchester and obviously London are where the culture is

Cos their museums & galleries hoarde it, and sometimes even make you pay to see it

It's what I love about Hepworth, Moore and Hockney in that they let us have their works, the former even displayed em on council estates for free

Imagine that, imagine that in the mind of the middle class liberal; 'they're too thick and racist to appreciate it' is the modern mentality

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

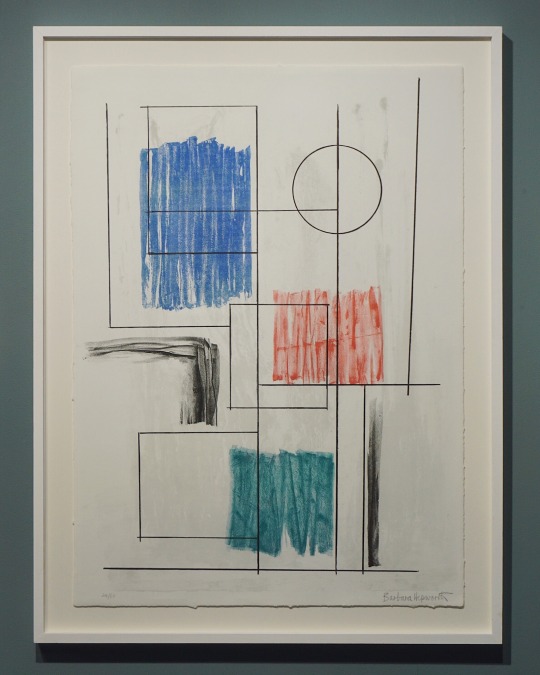

Barbara Hepworth,

Penwith Gallery /June 23

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

this is one of Barbara Hepworth's sculptures called Orpheus - by which we mean she made more than one of them

we deeply love this, and we saw it at her house in St Ives, Cornwall - so imagine our amazed delight the first time we visited Australia and saw its sibling in an art gallery in Sydney

the more delight because we were in the process of trying to write a novel that featured the lyre of Orpheus, and also the necessity of keeping certain of his body parts at opposite sides of the planet

and no, we haven't finished the bloody thing yet - it's been 24 years so far and executive dysfunction/performance anxiety is a bugger

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Barbara Hepworth Museum and Art Gallery in St Ives, Cornwall

2/7/2024

#Modern sculpture! my beloathed#art history#barbara hepworth#st ives#the tate#TATE#modern sculpture#sculpture

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

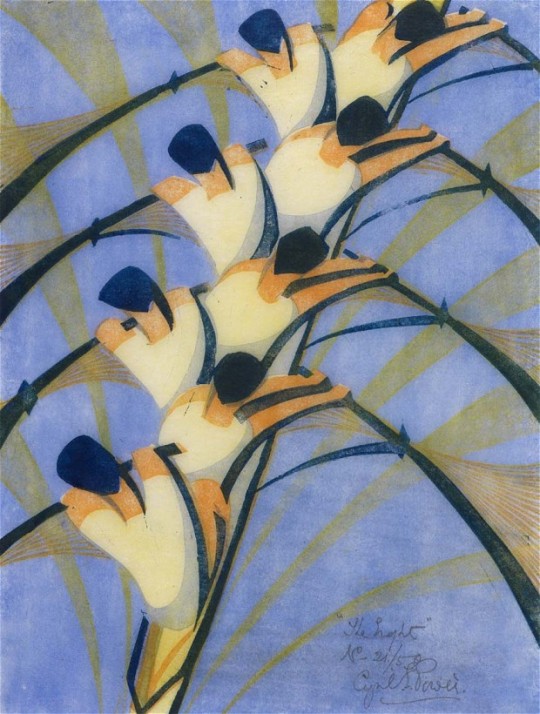

1 Cyril Power (1872-1951) UK The Eight reduction lino cut print (1930) 32.3×23.4cm

2 photographer unknown

economist.com

IT HAS become the custom nowadays,” wrote Claude Flight, a British artist, in 1926, “to go to a shop for the tools of one's trade.” Flight was scornful of shoppers and liked to make things for himself. He kept his own bees and championed the art of the linocut, believing that the use of cheap materials would help democratise art and bring it to the attention of the masses. For his own linocuts he insisted on “a sharp penknife—such a very rare thing among art students” and a gouge he fashioned by fitting a small wooden handle onto a rib he cut from an umbrella.

Hard to imagine health and safety regulations allowing children today to have such fun. But Flight, who was a friend to Henry Moore, Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth, inspired many pupils at the Grosvenor School of Modern Art, where he taught, wrote and organised exhibitions on linocuts.

Among the most famous was Cyril Power, an extraordinarily creative printmaker, born in 1872, who soaked up Flight's enthusiasms and gave them new force. Power drew on many influences—of the German Expressionists (who invented linocutting before the first world war), the Italian Futurists, the Vorticist prints and paintings of Wyndham Lewis—and the enthusiasm for speed and movement that marked the work of so many artists of the period, from Natalya Goncharova to Marcel Duchamp.

While the work of the Germans, Italians, French and Russians has become very well known, the prints and linocuts made by Power and his fellow British artists have lingered in the shadows. An inspired little exhibition—the first major show of Modernist British prints in America, which began earlier this year at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and is now at the Metropolitan Museum in New York—will help change that. So too will a newly opened show at a private gallery in London that gathers together for the first time prints of all 46 of Power's linocuts. Some are for sale; others have been lent by museums and private collectors, of which the most important are two New Yorkers, Leslie and Johanna Garfield.

The first impression of the Power show is that he lived his life in reverse. Until he was almost 50 he followed in the professional footsteps of both his father and his grandfather and practised as an architect, making a name for himself also as the author of an erudite study entitled “English Medieval Architecture”. Then, as Philip Vann explains in an elegant essay that accompanies the show, he “embarked on a kind of Gauguin-esque adventure”, leaving his wife and four children to enrol in art school in the company of a 24-year-old artist, Sybil Andrews.

The early prints in the show were made by a middle-aged man and it shows. In black-and-white there is a bridge at Rickmansworth, a street corner in the sleepy Suffolk town of Lavenham. Then suddenly the movement of the windmill in “Elmers Mill, Woolpit” gives an indication of what is to come. Starting in 1930, when he was already 58, Power takes to speed as if he had taken personal charge of the Futurist manifesto, which C.R.W. Nevinson co-signed with an incendiary Italian, Filippo Marinetti, in 1914, with the words “Forward! HURRAH for motors! HURRAH for speed!…HURRAH for lightning!”

Power allows light, noise and speed into everything he sees. Using a series of easily recognised colours, particularly “Chinese orange”, “chrome orange”, “viridian” and “Chinese blue”, he created images of merry-go-rounds, rowers, acrobats, dancers, runners, hockey players and, of course—given that some of his influences were Italian—beautiful cars.

The most successful are those, like “The Eight”, in which the element of formal design is most visible. But Power's vision as an artist really comes to the fore in works containing a hint of menace. The bourgeois-assaulting spirit of Italian Futurism, Mr Vann explains, had fallen into the malign hands of Mussolini and was about to give way to Fascism, while Freud's and Jung's obsessions with the unconscious were increasingly helping to throw up visions of fears, hopes and dreams.

“Monsignor St Thomas” (1931, pictured at left) is a brilliant working of the murder in the cathedral of Thomas à Beckett, but it is technically skilful rather than edgy. The really potent, and most modern-looking, of Power's linocuts are those that lead the viewer right to the edge. These start with “Tennis” (1933, below), a magnificent rendering not just of the energy of the centre court, but of the physical and psychological effects of slicing and spinning—sport at its most gladiatorial.

As the 1930s move towards totalitarianism and then war, Power's work takes on a darker hue. The tube trains and the escalators of the London subway system provide ample opportunity for exploring man's addiction to the rat race. Two further works seem remarkably prescient. In 1934 Power made a linocut which he called “Exam Room”, full of hunched-up concentration and a complex set of figures that show, in turn, fear, nerves, gloating, dreaming—and one who is slyly distracting a neighbour. Watching over them is the overbearing timekeeper and the all-seeing eyes in the ceiling.

Similarly, “Air Raid”, which Power made in 1935 and which has been lent to this show by the RAF Museum in Hendon, is an extraordinarily filmic response to a period of history the artist had not yet even seen. It would be another five years before the start of the Battle of Britain would make such imagery routine. Cyril Power was not just an artist, he was a visionary

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

#photography#photographer#clickasnap#yorkshire#travel#River Calder#West Yorkshire#Wakefield#Hepworth#Hepworth Gallery

0 notes

Photo

Barbara Hepworth (1903 -1975)

Barbara Hepworth, Head (Mykonos), 1959-60 | Offer Waterman

Barbara Hepworth, Zennor, 1966 | RWA Bristol

Educator Resource Packet: Two Figures (Menhirs) by Barbara Hepworth | The Art Institute of Chicago

BARBARA HEPWORTH, Elegy III, 1966-67 | Mira Godard

Barbara Hepworth | Pace Gallery

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On a summer evening last year, on a clifftop by Porthmeor Beach in Cornwall, southwest England, passers-by might have seen an artist in a tracksuit painting the sunset. Did people hassle him? “Obviously,” says Jake Grewal, the artist in question. “But in a really nice way. A dog would come up and sniff my cadmium paints. I’d be like, ‘Please take your dog away, it’s poisonous. I’m scared he’s going to die.’”It’s surprising to think of a young artist today standing at an easel en plein air like Monet. But the gorgeous results of Grewal’s work are currently on show at the prestigious Studio Voltaire in London. Made up of 11 paintings completed in the past year, the London-based artist’s new exhibition is called “Under the Same Sky.” The smaller landscapes were made in Cornwall; Grewal had a monthlong residency at Porthmeor studios, where artists including Francis Bacon and Ben Nicholson once painted. “I could hear the sound of the ocean while I was in the studio,” Grewal remembers. “The residency came at a time when I had just turned 30, just had a breakup, and then I went to the bottom end of the country to be on my own. It allowed me to paint outside, and to experience those emotions in an organic way.”The other big influence was Grewal’s first trip to India, which also took place last year. Previously, he would get irritated when people attributed the haziness of his landscapes, and their remarkable use of color, to his Indian heritage on his father’s side (his mother is Welsh). “But when I got there, I understood where people were coming from, because there are strange colors there that you wouldn’t normally see next to one another. And there is this haze everywhere.”Jake Grewal, Nurturing Waters, 2024.Photo by Ben Westoby, © Jake Grewal. Courtesy of the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery. Although Trustlands, a long landscape in the show, is inspired by a photograph Grewal took in Goa, none of the beaches, rocks, or seascapes he paints are taken directly from life: they are composites of places he’s been, or scenes from his imagination. Often, the paintings contain naked male figures with their faces turned from the viewer, half-hidden in nature or clambering over rocks, as in the almost 19-footlong canvas The Cycle of Erosion. Those figures are self-portraits of a kind, but they also suggest enquiry, sexuality, and hope. “I wanted the show to be about freedom, openness, a memory of warmth, and a kind of contentment,” he says.Grewal’s dreamy and confident paintings have won the artist an ardent following. The director Luca Guadagnino commissioned him to paint a work to use as a poster for his film Queer; before that, Grewal’s 2022 charcoal drawing The Sentimentality of Nature was acquired by Hepworth Wakefield, a renowned British museum, after he won the inaugural J.W. Anderson Collections Fund. The artist has a remarkable grasp of color, which he says is innate, and while he loves to immerse himself in art history, he is also keen to give himself technical challenges—for instance, by making charcoal look like paint and vice-versa.Usually, he’s at his studio in east London from 11 AM to 6 PM. It takes him about three months to make a large painting, and he focuses on three to five canvases at a time. While he works, he listens to NPR’s Tiny Desk series, or to lectures by artists he admires like Peter Doig or Marlene Dumas. “Sometimes you can feel as if the only thing that matters is the show you’re making,” he says. “To think about other people’s perspectives on art and making can be quite liberating.”Photo by Joyce NGPhoto by Joyce NGGrewal was brought up in London and was inspired at school by an art teacher who taught him about J.M.W. Turner, Howard Hodgkin, and Barbara Hepworth. In 2013, he left for Brighton University, on the English south coast, to study fine art. “I was trying to do this thing where I was marrying drawing and painting,” he says. He became disillusioned, however, when he realized that to get a good grade, he was better off doing what the course required rather than genuinely experimenting.After graduating in 2018, he had two paintings in a group show that were damaged in a fire. The insurance payout meant that he could afford to take a course at London’s Royal Drawing School, and those two years set him on the track he’s on today. The only problem was that in order to save money he had to live with his parents, which made him feel, he says, as though “my life was on hold, and I couldn’t develop personally.” Potential boyfriends would be put off by the fact that he hadn’t left home; a sense of yearning for the unobtainable is still discernible in his pictures, although, he says, “I’ve definitely had my fill since.”Covid meant that he also had to stay in his parents’ house throughout lockdown, but that turned out to be another transformative period. “I discovered Kundalini yoga, which is quite spiritual, all about breath work,” Grewal says. “Doing a repetitive practice that was open and freeing, at a time when everything felt so restrictive and closed in, filled me with this audacious ease. I would go out and draw in the park every day.” Since the art world had shut down, there was no pressure on Grewal to launch his career. He thinks that having this break was crucial: “Things need a kind of gestation period.”Jake Grewal Trustlands, 2024.Photo by Ben Westoby, © Jake Grewal. Courtesy of the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery.After lockdown, Grewal started selling his work on Instagram, and then in 2020 took part in the influential graduate show New Contemporaries, which, along with a show the following year at Jhaveri Contemporary in India with Prem Sahib and Sunil Gupta, “brought a more serious engagement” with his practice. He acquired representation by the gallery Thomas Dane, and last year participated in an exhibition at Pallant House, in Chichester, Sussex, alongside well-known “neo-romantic” artists. “I was looking at the darker elements of being a queer person, and of the landscape, and that’s something the British neo-romantics capture quite well.”Grewal says that his work expresses some of the angst, as well as the joy, he feels as a queer person of color. “There’s a sense of othering that’s inherent to the queer experience,” he says. “Also, for me, I have felt a displacement because of my identity. There’s a question of whether, or where, you fit in.” In the new show, Grewal also experiments with a new kind of mysticism, which he attributes to his aunt. “She’s quite woo-woo and into Native American ways of thinking,” he says. “And apparently there’s this kind of spiritual veil, and when you’re by the coast, that’s where the veil is thinnest, and you can easily access other dimensions. So, I was thinking about that too.” Source link

0 notes

Photo

On a summer evening last year, on a clifftop by Porthmeor Beach in Cornwall, southwest England, passers-by might have seen an artist in a tracksuit painting the sunset. Did people hassle him? “Obviously,” says Jake Grewal, the artist in question. “But in a really nice way. A dog would come up and sniff my cadmium paints. I’d be like, ‘Please take your dog away, it’s poisonous. I’m scared he’s going to die.’”It’s surprising to think of a young artist today standing at an easel en plein air like Monet. But the gorgeous results of Grewal’s work are currently on show at the prestigious Studio Voltaire in London. Made up of 11 paintings completed in the past year, the London-based artist’s new exhibition is called “Under the Same Sky.” The smaller landscapes were made in Cornwall; Grewal had a monthlong residency at Porthmeor studios, where artists including Francis Bacon and Ben Nicholson once painted. “I could hear the sound of the ocean while I was in the studio,” Grewal remembers. “The residency came at a time when I had just turned 30, just had a breakup, and then I went to the bottom end of the country to be on my own. It allowed me to paint outside, and to experience those emotions in an organic way.”The other big influence was Grewal’s first trip to India, which also took place last year. Previously, he would get irritated when people attributed the haziness of his landscapes, and their remarkable use of color, to his Indian heritage on his father’s side (his mother is Welsh). “But when I got there, I understood where people were coming from, because there are strange colors there that you wouldn’t normally see next to one another. And there is this haze everywhere.”Jake Grewal, Nurturing Waters, 2024.Photo by Ben Westoby, © Jake Grewal. Courtesy of the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery. Although Trustlands, a long landscape in the show, is inspired by a photograph Grewal took in Goa, none of the beaches, rocks, or seascapes he paints are taken directly from life: they are composites of places he’s been, or scenes from his imagination. Often, the paintings contain naked male figures with their faces turned from the viewer, half-hidden in nature or clambering over rocks, as in the almost 19-footlong canvas The Cycle of Erosion. Those figures are self-portraits of a kind, but they also suggest enquiry, sexuality, and hope. “I wanted the show to be about freedom, openness, a memory of warmth, and a kind of contentment,” he says.Grewal’s dreamy and confident paintings have won the artist an ardent following. The director Luca Guadagnino commissioned him to paint a work to use as a poster for his film Queer; before that, Grewal’s 2022 charcoal drawing The Sentimentality of Nature was acquired by Hepworth Wakefield, a renowned British museum, after he won the inaugural J.W. Anderson Collections Fund. The artist has a remarkable grasp of color, which he says is innate, and while he loves to immerse himself in art history, he is also keen to give himself technical challenges—for instance, by making charcoal look like paint and vice-versa.Usually, he’s at his studio in east London from 11 AM to 6 PM. It takes him about three months to make a large painting, and he focuses on three to five canvases at a time. While he works, he listens to NPR’s Tiny Desk series, or to lectures by artists he admires like Peter Doig or Marlene Dumas. “Sometimes you can feel as if the only thing that matters is the show you’re making,” he says. “To think about other people’s perspectives on art and making can be quite liberating.”Photo by Joyce NGPhoto by Joyce NGGrewal was brought up in London and was inspired at school by an art teacher who taught him about J.M.W. Turner, Howard Hodgkin, and Barbara Hepworth. In 2013, he left for Brighton University, on the English south coast, to study fine art. “I was trying to do this thing where I was marrying drawing and painting,” he says. He became disillusioned, however, when he realized that to get a good grade, he was better off doing what the course required rather than genuinely experimenting.After graduating in 2018, he had two paintings in a group show that were damaged in a fire. The insurance payout meant that he could afford to take a course at London’s Royal Drawing School, and those two years set him on the track he’s on today. The only problem was that in order to save money he had to live with his parents, which made him feel, he says, as though “my life was on hold, and I couldn’t develop personally.” Potential boyfriends would be put off by the fact that he hadn’t left home; a sense of yearning for the unobtainable is still discernible in his pictures, although, he says, “I’ve definitely had my fill since.”Covid meant that he also had to stay in his parents’ house throughout lockdown, but that turned out to be another transformative period. “I discovered Kundalini yoga, which is quite spiritual, all about breath work,” Grewal says. “Doing a repetitive practice that was open and freeing, at a time when everything felt so restrictive and closed in, filled me with this audacious ease. I would go out and draw in the park every day.” Since the art world had shut down, there was no pressure on Grewal to launch his career. He thinks that having this break was crucial: “Things need a kind of gestation period.”Jake Grewal Trustlands, 2024.Photo by Ben Westoby, © Jake Grewal. Courtesy of the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery.After lockdown, Grewal started selling his work on Instagram, and then in 2020 took part in the influential graduate show New Contemporaries, which, along with a show the following year at Jhaveri Contemporary in India with Prem Sahib and Sunil Gupta, “brought a more serious engagement” with his practice. He acquired representation by the gallery Thomas Dane, and last year participated in an exhibition at Pallant House, in Chichester, Sussex, alongside well-known “neo-romantic” artists. “I was looking at the darker elements of being a queer person, and of the landscape, and that’s something the British neo-romantics capture quite well.”Grewal says that his work expresses some of the angst, as well as the joy, he feels as a queer person of color. “There’s a sense of othering that’s inherent to the queer experience,” he says. “Also, for me, I have felt a displacement because of my identity. There’s a question of whether, or where, you fit in.” In the new show, Grewal also experiments with a new kind of mysticism, which he attributes to his aunt. “She’s quite woo-woo and into Native American ways of thinking,” he says. “And apparently there’s this kind of spiritual veil, and when you’re by the coast, that’s where the veil is thinnest, and you can easily access other dimensions. So, I was thinking about that too.” Source link

0 notes