#Henry Heveningham

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Sir John Shelton (1476/7 – 1539) of Shelton in Norfolk, England, was a courtier to King Henry VIII. Through his marriage to Anne Boleyn, a sister and co-heiress of Thomas Boleyn, 1st Earl of Wiltshire of Blickling Hall in Norfolk, he became an uncle of Queen Anne Boleyn, the second wife of King Henry VIII. He was appointed comptroller of the joint household of Princesses Mary and Elizabeth, the King's daughters, and together with his wife was Governor to the King's children.

and then:

Sir John Shelton (b. in or before 1503, d. 1558) was the eldest son of Sir John Shelton and Anne Boleyn, the aunt of Queen Anne Boleyn. John's sister, Mary Shelton, who married Sir John Heveningham, was possibly the mistress of Henry VIII of England during 1535. He married Margaret Parker, daughter of Henry Parker, 10th Baron Morley.

me trying to research like, why are there are so many john sheltons...

1 note

·

View note

Quote

If music be the food of love, Sing on till I am fill’d with joy; For then my list’ning soul you move To pleasures that can never cloy. Your eyes, your mien, your tongue declare That you are music ev’rywhere. Pleasures invade both eye and ear, So fierce the transports are, they wound, And all my senses feasted are, Tho’ yet the treat is only sound, Sure I must perish by your charms, Unless you save me in your arms.

Henry Heveningham for a song by Henry Purcell

#the first line is from shakespeare I know#Henry Heveningham#Henry Purcell#Words and more words#Quotes#Music

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

If Music Be the Food of Love - SSAATTBB (2017) - TRAN

On the famous poem by Col. Henry Heveningham (1651-1700)

-

Composer: Dylan Tran (1994-)

Performed by: Pacific Edge Voices in Berkeley, CA

Directed by Dr. Lynne Morrow

YouTube Source Channel: Dylan Tran

Run-time: 6 min 27 sec

-

@theseeker1864

#dylan tran#pacific edge voices#dr. lynne morrow#col. henry heveningham#music#composition#audio#video#run-time: 6 min 27 sec#if music be the food of love - SSAATTBB (2017) - TRAN

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

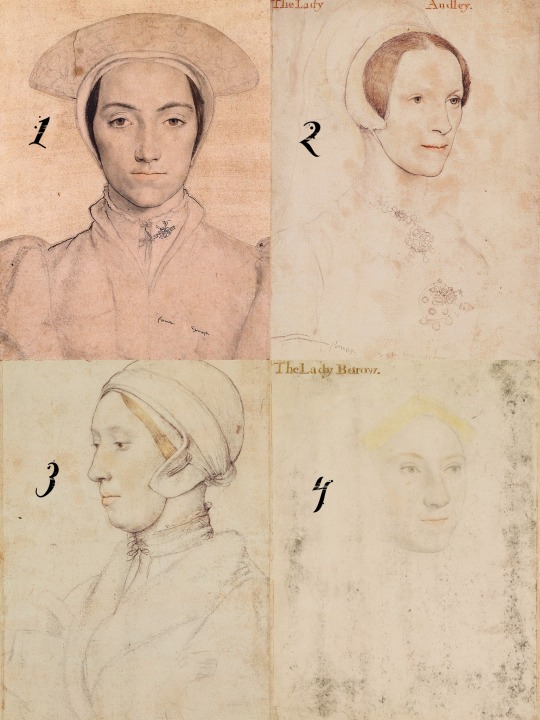

The Women of Hans Holbein Sketches

1. The sitter in the portrait is unknown, but it has been suspected to be of Amalia of Cleves, the sister of Anne of Cleves.

2. Elizabeth Audley, the wife of Thomas Audley, 1st Baron Audley of Walden

3. The sitter in the portrait is unknown, but it has been suspect to be of Anne Boleyn.

4. Alice Burgh, the wife of Thomas Burgh who was a part of the household of Prince Edward (later Edward VI).

5. Margaret Butts, a lady-in-waiting to Princess Mary (later Mary I).

6. Anne Cresarce, a ward of Thomas More.

7. Elizabeth Dauncey, a daughter of Thomas More.

8. Margaret, Marchioness of Dorset, a godmother to Princess Elizabeth (later Elizabeth I).

9. Margaret Elyot.

10. Margaret Giggs, a ward of Thomas More.

11. Cicely Heron, a daughter of Thomas More.

12. Mary Heveningham, a first cousin to Anne Boleyn and suspected mistress to Henry VIII.

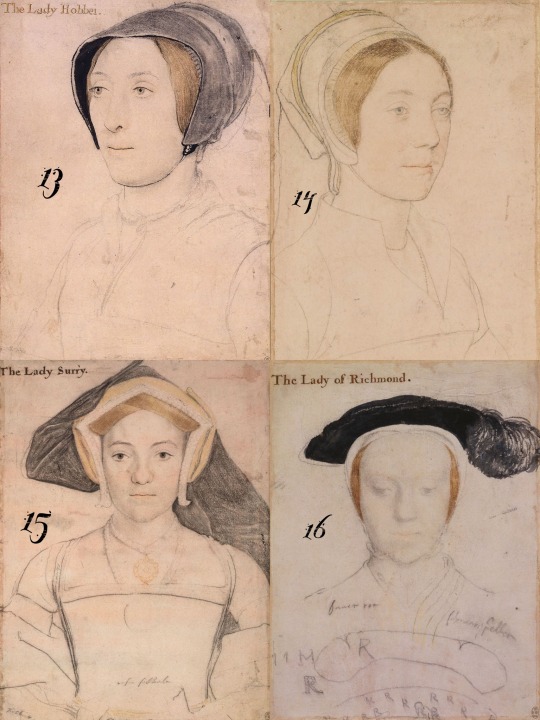

13. Elizabeth Hoby, was a part of Katherine Parr’s inner circle.

14. The sitter in the portrait is unknown, but it has been suspected to be of Katherine Howard.

15. Frances, Countess of Surrey, the wife of Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey.

16. Mary, Duchess of Richmond and Somerset, the wife of Henry VIII’s illegitimate son Henry Fitzroy.

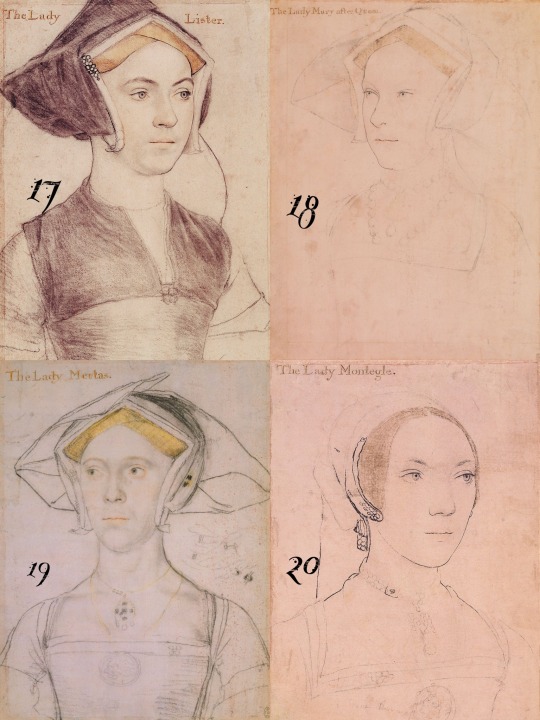

17. Probably of Jane Lister.

18. Princess Mary (later Mary I).

19. Joan Meautas, lady of the privy chamber to Jane Seymour.

20. Mary Monteagle, a daughter of Charles Brandon.

21. Formerly suspected to be of Jane Boleyn, but is now believed to be of Grace Parker.

22. Could be any of the three wives of Robert Radcliffe, 1st Earl of Sussex, but is probably his third wife Mary Arundell.

23. Elizabeth Rich, the wife of Richard Rich, 1st Baron Rich.

24. Jane Seymour.

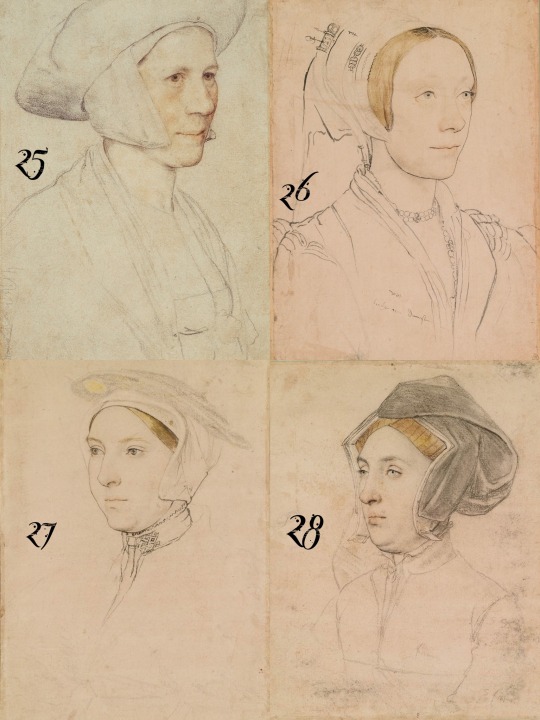

25. Unknown sitter.

26. Unknown sitter.

27. Unknown sitter.

28. Unknown sitter.

29. Unknown sitter, but has been suspected to be of Anne Herbert, the sister of Katherine Parr.

30. Unknown sitter.

31. Unknown sitter, but has been suspected to be of Maud Green, the mother of Katherine Parr.

32. Elizabeth Vaux, a first cousin to Katherine Parr.

33. Catherine Willoughby, the wife of Charles Brandon.

34. Mary Zouch, a lady-in-waiting to Anne Boleyn.

35. Mary Guilford, the wife of Henry Guilford.

#hans holbein#history#tudor history#anne of cleves#anne boleyn#katherine howard#katherine parr#henry viii#art

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

P. 4/?, Mary Shelton and Mary Fitzroy

One of Anne Boleyn’s maids of honor, and cousin, was Mary Shelton, the daughter of Sir John Shelton and Lady Anne Boleyn, the aunt of Queen Anne Boleyn. She was one of 10 children, although she largely overshadowed them. She was born around 1510-1515, although her birth date is unknown. She became Anne’s maid of honor at an unknown date, although it is known she was her maid. Evidence of this is from when Anne apparently lightly chided Mary for writing poetry in her prayer book. She was also said to be a great beauty, one ambassador saying that Christina of Denmark was beautiful and looked like “Mistress Shelton”, who was probably Mary. She was engaged to Thomas Clere, a close friend of Henry Howard, but he died before they were married. She then married Anthony Heveningham, and after he died, Philip Appleyard. She was one of the main contributors of the Devonshire Manuscript, a manuscript of poems in the 16th century. She was a proto feminist, changing lyrics of poetry to a more feminine slant, according to Elizabeth Norton. She was a close friend of Mary Fitzroy, nee Howard.

Mary Fitzroy, Duchess of Richmond, maiden name Howard, was the daughter of the Duke of Norfolk, Thomas Howard, and Elizabeth Stafford, daughter of the Duke of Buckingham. She was born in 1519 and was a cousin of Anne Boleyn, through her father and Anne’s mom, as they were siblings. Anne Boleyn negotiated a marriage between Mary Howard and Henry Fitzroy, the illegitimate son of Henry VIII. She was close to Margaret Douglas, Henry VIII’s niece, and Mary Shelton, another cousin of Anne Boleyn. She, Margaret and Mary were the main contributors of the Devonshire Manuscript. Mary Fitzroy had been a part of Anne Boleyn’s household before her ascent to Queenhood, surprisingly. After her husband’s and Anne Boleyn’s death, she mostly fell into obscurity, but it’s known she served Anne of Cleves. After the death of her brother, Henry Howard, she took care of his children, living an isolated life until she died in 1557.

Pictured below is Mary Shelton and Mary Fitzroy.

P. 1 P. 2 P. 3

#ladies in waiting#maids of honor#mary shelton#mary heveningham#mary appleyard#mary fitzroy#mary howard#anne boleyn

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This very Car won the 1986 Monte Carlo rally with Henri Toivonen at the wheel. #lanciadeltas4 #lanciadelta #deltas4 #delta #groupbrally #rally #rallying #martiniracing #classiccar #cars #carsofinstagram #heveninghamconcours (at Heveningham Hall)

#classiccar#lanciadelta#carsofinstagram#deltas4#cars#rally#heveninghamconcours#lanciadeltas4#martiniracing#rallying#groupbrally#delta

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

History of Suffolk county’s architecture

The architecture of the county of Suffolk is a mix of colour and character, with timber-frame and flint, pargetting and thatched roofs, moats and chimney stacks

By Jenny Woolf

Scattered around the flinty-grey churches of Suffolk, you will sometimes see groups of brightly-coloured cottages, for all the world like flowers growing about the stumps of dark oaks. This contrast is typical of Suffolk, for this Eastern county has no quarries or brickworks, and its people have always collected bits and pieces with which to create their buildings. As a result, many Suffolk buildings are glorious jumble of flints from the beaches, rushes from the marshland, and clay and timber from the farms.

That is not to say that Suffolk lacks grand homes. There is Elveden Hall, where Angelina Jolie filmed part of Lara Croft: Tomb Raider, not to mention Framlingham Castle and Ickworth House. Yet somehow it is often the humbler homes that engage the emotions and delight the eye.

Just inside Suffolk’s southern border, Long Melford’s rambling village street is lined higgledy-piggledy with five centuries’ worth of typical vernacular houses. Some are plastered, some are timbered, and some boast the enormously tall chimney-stacks that betray their Tudor origin.

Five hundred years ago, those quaint buildings represented the last word in homes and warehouses for hard-nosed modern businessmen, for medieval Long Melford was a thrusting, busy place. Like many other Suffolk towns – notably beautiful Lavenham – it was built with money from the cloth trade, and it did very well indeed. In Lavenham, the beautiful timber-frame Guildhall of the Wool Guild of Corpus Christi still stands in the market place and is now under the care of the National Trust, with a museum and exhibitions on the medieval cloth industry.

There were around 30 weaving businesses in Melford, plus associated craftsmen like dyers who made pigments from the plants they gathered in the surrounding countryside. Yellows and greens came from nettles and cow-parsley, reds from ladies-bedstraw, and mauves from damsons and sloes.

Indeed, it was probably the dyers of Suffolk who first stumbled upon the idea of Suffolk Pink – an exquisite example being the pink cottages by St Mary’s Church in the village of Cavendish. The Suffolk Pink concept has now become so popular that a new variety of apple (discovered in Suffolk, of course) has been named for it.

Traditionally, though, it is a style of decoration: some have diamond-paned windows and oversailing upper storeys. Others are medieval moated halls, or cottages with low doors and steep thatched roofs. What they all share is their colour – pink. Shell-pink, rose-pink, geranium, even raspberry.

Centuries ago, these pink shades were created by adding natural substances to traditional lime whitewash. The cottager might perhaps stir in some elderberries – small black globes that release an amazing carmine red – or dried blood, or crumbled red earth.

Long Melford’s wealthy burghers also built the longest church in Suffolk – the amazing Holy Trinity. The size of a cathedral, it is as splendid inside as out. It contains, among other treasures, Suffolk’s largest collection of medieval glass.

Most of this glass commemorated the Clopton family, who lived in the village’s Kentwell Hall. A large brick mansion, Kentwell is essentially Tudor, with a Gothic centre block. Its latest owners insist that it is no stately home, just a family dwelling – albeit a very unusual one.

Kentwell has moats as well, and so do many smaller old Suffolk houses. By the 1500s, moats had become popular ornamental features and although many of Suffolk’s smaller moated houses are not open regularly to the public, although many offer private tours by arrangement. However, some have exquisite gardens which they do open during the summer months, such as those at Helmingham Hall, for example, home of the Tollemache family for 500 years. Here, there are two drawbridges which are pulled up every night as they have been since 1510, and the hall reverts to being an island, protected by its wide moat.

The historical gardens at moated Otley Hall, just north of Ipswich, are open by arrangement, and they include such curiosities as a croquet lawn and a nuttery. The gardens of nearby Heveningham Hall are also often open, and they contain many secret bridges and tunnels, as well as an elaborate parterre.

Parterres, popular in the 16th and 17th centuries, capture the curlicued decorative style of this period perfectly. They are hard to create, hard to maintain, and you cannot use them for much; so they made a perfect status symbol.

So, too, did the pargeting which became popular in Suffolk and adorned the walls of so many Suffolk houses. First seen around Henry VIII’s time, this elaborate custom-made plaster decoration has undergone something of a revival in recent years, although few modern displays can equal the best of the old ones.

In fact, gorgeous though pargeting looks, expert Tim Buxbaum believes that the craft developed partly as a way of covering up second-rate timbering or untidy new extensions on the outside of houses. “Coating the structure with a decorative coat of plaster was a good way to give an old building a new lease of life,” he says.

Buxbaum, who runs a conservationist architectural practice in Lower Ufford, draws special attention to the Ancient House in Ipswich, one of the finest surviving examples of pargeting in the country.

Commissioned in the 1600s by Robert Sparrowe, a widely travelled spice merchant, the house carries representations of Neptune with a trident, riding a sea-horse, St George and the Dragon, and Atlas carrying the world upon his shoulders – and that is just a fraction of its ebullient imagery.

Suffolk’s churches offer an exterior contrast to its ornate or colourful houses. One of the most famous Suffolk churches is Holy Trinity, Blythburgh, near the coast. It is full of light yet also shimmers with mystery. Inside, its wooden roof is covered in carved angels. Not far away, at Huntingfield, the rector’s wife, Mildred Holland, hitched up her skirts, climbed onto scaffolding and lay flat on her back for eight months in the 1860s to paint a stunning, Pugin-esque masterpiece of Victorian Gothic angels all over the ceiling.

In contrast, the parish church of St Peter and St Paul of Lavenham is typical of the wool churches of the county – completed by 1530. After visiting the church, stroll down the hill into the town, which has nearly 350 listed buildings. It’s regarded as one of the finest surviving medieval towns in England. Some parts of the town must still look much as they did when Elizabeth I made a grand state visit in 1578.

Indeed, when Robert Louis Stevenson visited Lavenham in 1873, he thought it looked, even then, like “what ought to be in a novel.” Now, of course, he would be imagining Angelina Jolie in a movie. Which all goes to show that times may change, but Suffolk does not.

Editor’s choice

Invitation to View allows small groups of visitors a great chance to see private historic houses which are not otherwise open

Constable and Gainsborough came from Suffolk and drew inspiration from the landscapes. Admire Constable’s unspoiled Flatford Mill near East Bergholt, with the Hay Wain’s famous Willie Lott’s Cottage. Visit the nearby National Trust museum and Gainsborough’s House museum in Sudbury which has a huge collection of the painter’s works.

The Great House (5-star), Lavenham: 15th-century restaurant with rooms on Lavenham’s Market Place, across from the Guildhall

The Suffolk Punch Trust in Hollesley: visitor centre and museum for these working horses with the longest written pedigree in the world

Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds: beautifully restored Georgian theatre, one of the earliest theatres in the country

The Swan at Lavenham (4-star), The Old Bar has a collection of memorabilia from American airmen stationed at Lavenham Airfield during World War II

Learn more about our Kings and Queens, castles and cathedrals, countryside and coastline in every issue of BRITAIN magazine

The post History of Suffolk county’s architecture appeared first on Britain Magazine | The official magazine of Visit Britain | Best of British History, Royal Family,Travel and Culture.

Britain Magazine | The official magazine of Visit Britain | Best of British History, Royal Family,Travel and Culture https://www.britain-magazine.com/features/history/suffolk-architecture/

source https://coragemonik.wordpress.com/2020/03/25/history-of-suffolk-countys-architecture/

0 notes

Text

Program Notes from Ever-Fixed Mark: A Senior Voice Recital

An Introduction

Last year, I presented a junior lecture recital entitled “Symphonic Shakespeare”, a study of the adaptations of playwright William Shakespeare’s texts into western Classical music. It only made sense that I should continue learning about the ways in which his timeless narratives and characters were rewritten, redefined, or interpreted by the music in which they were set. This recital aims to address the role of the soprano, which I have come to find in many contexts represents the love interest. It is no secret that Shakespeare’s writing embodies a type of romance, eroticism, and affection that shapes the way we as a society approach and understand relationships. Aside from understanding the significance of adaptation, then, this recital is to showcase the multifaceted and complex concept of “love”.

About the title: “Ever-Fixed Mark” is taken from Sonnet 116, in which he writes: “Love is not love / Which alters when it alteration finds, / Or bends with the remover to remove. / O no! it is an ever-fixed mark,” (116: 2-8). I thought it was fitting, as all of the songs on the program have to do with love or some shape of it, to name my recital. Additionally, written notation, music itself is but an ever-fixed mark, bound to exist so long as the score, or even the melody from rote, is maintained.

“It was a lover and his lass”

The arts have intertwined for as long as they’ve existed as a means of expression—and in the English Renaissance, especially on the stage of the Elizabethan theatre, so they did. “It was a lover and his lass” was a diegetic (meaning the music was a witnessed part of the performance) number in Act V, scene III of As You Like It, sung by one of the pages to the betrothed Audrey and Touchstone. In the scene, Touchstone expresses dislike of the song, as it represents little of actual love; its lyrics are ridiculous, overall, it’s silly, and there’s really no substance—but the music, just as love itself, is beautiful despite the frivolity of the antics happening lyrically.

Thomas Morley (1557-1602) was an English renaissance secular and sacred composer, singer, organist, and publisher, probably most renowned today for his madrigals (secular a cappella pieces for six to eight voices). He published this tune in his anthology, First Book of Ayres, in 1600. It contained English songs for voice and lute, and although it cannot be confirmed that this version of the song was used in the production that William Shakespeare would have presented at the Globe, it is known that Morley and Shakespeare, two creative contemporaries, did not collaborate accidentally.

“If Music Be The Food of Love”

Following his death, Shakespeare’s works (as well as those of other authors) were disseminated into spin-offs and retellings by other playwrights and publishers. His portfolio edition of these stories would disappear from the repertoire, but nonetheless influenced English literature and drama for centuries to come.

Colonel Henry Heveningham (1651-1700) created a text, adapted from Duke Orsino’s opening dialogue in Twelfth Night I.i.1-15 as he laments to his attendant Curio about his failed attempts at wooing the fair Olivia. Compare the original text to the lyrics below:

Although it certainly comes from the same place (Duke Orsino’s desperate, fascinated appetite for a humanistic satisfaction be it tangible or expressed through creative means) it’s obviously different. The latter, by Heveningham, is written as a ballad, between two lovers, instead of an address. Henry Purcell sets this strophic text with word painting, the longing emphasised by a melody that slowly climbs the staff with accompanying crescendo, that eventually falls dramatically at the end of the verse, relinquishing itself to the accompaniment and too, hypothetically, the object of the serenade.

“O, let me weep,” from The Fairy Queen

The Fairy Queen is another example of Shakespeare’s work being adapted after his death. This particular semi-opera, first performed in 1692, is based on Midsummer Night’s Dream—in the spoken moments, the original text remains unchanged, but Henry Purcell (1659-1695) and his librettist Elkanah Settle (1648-1724) change some of the text in ‘masques’, or musical scenes prompted by magical, supernatural, or drunken characters, to fit seventeenth-century dramatic conventions. “O, let me weep”, or as it is more commonly called, ‘The Plaint’ is one of these masques. It was written after the opera had already premiered, as a kind of showcase piece for countertenor or soprano performer—superstars in their own right during the Baroque era.

The Baroque era was the last period in which English composers held strong relevance until the turn of the twentieth century, compared to their continental contemporaries. Henry Purcell was a powerhouse in this regard; he was proficient in various styles of counterpoint yet mainly championed the English Baroque style in his works, composed in both sacred and secular genres with substantial popularity, and also composed for theatre and opera.

“V’adoro, pupille” from Giulio Cesare

Shakespeare wrote the historical drama Julius Caesar in Spring of 1599. The political tensions in England were high, as Queen Elizabeth reached the end of her reign. Subjects of republicanism versus monarchy were circulating, and to depict the killing of a king would be tantamount to treason. However, by using Plutarch’s Lives as his source material, an author that Queen Elizabeth I studied, he effectively avoided the threat of creative persecution. In the eighteenth century, however, the subject of a political history was ripe for opera seria—and librettist Nicola Francesco Haym (1678-1729) created Giulio Cesare in Egitto with Georg Frederic Händel (1685-1759) for the Royal Academy of Music in 1724 during the composer’s tenure at the English court. It was a relatively successful work, and one of Händel’s more (if not most) well known Italian operas to date.

Her presence may be more pertinent in the related Shakespearean tragedy, Antony and Cleopatra, but in Händel’s opera, Cleopatra’s affairs are everything but ignored. In this aria, she admires the young, handsome Julius Caesar, lamenting their never to be love, as she’s far past her courting years:

Fünf Lieder WoO post. 22 (Ophelia-Lieder)

The German translations of many of Shakespeare’s plays appeared in the early 19th century, sparked by Schlegel-Tieck’s publication. Among other composers to set Shakespeare’s works, Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) approached the setting of Ophelia’s songs in a really interesting way by honouring the sing-song style of the text and folly and falter of rhythm in her speeches, and too had a particular choice of harmonic language. He uses very basic piano accompaniment that resembles a kind of pastorale Renaissance style—in the first and second songs, simpler, lute-like voicings and strophic melodies in the soprano. In the third setting, “Auf Morgen its Sankt Valentin’s Tag,” we hear an off-kiltered compound duple meter that almost feels like the pillars of a village dance. In the fourth and fifth songs, Brahms alludes to a sort of chorale or hymn form, but more notably uses a mixture of modes (variations of scales) between A-flat major and its relative minor key of F. This simple relationship ties together more antiquated musical forms and the Romantic style, which nineteenth-century composers defined with manipulations of harmony and tonal center.

The english translation given is not a direct interpretation of the German lyrics, rather the original text from Hamlet Act IV scene v, lines 23-26, 29-33, 48-55, 165-187, and 190-201, respectively.

“Je veux vivre,” from Roméo et Juliette

The stage of the French grand opera is the perfect setting for the melancholic story of the teenage star-crossed lovers. After his major success, Faust, Charles Gounod (1818-1893) and his librettists, Jules Barbier (1825-1901) and Michel Carré (1821-1872) premiered the opera at the Théâtre Lyrique Impérial du Châtelet, Paris in April 1859, and it rose to great success with over three hundred performances in the first eight years of its lifetime.

Juliette’s aria is a testament to teenage life and fleeting crushes. The viennese waltz setting is fitting for the scene in Act I, when all of the characters are meeting at the Capulet estate for her birthday. Juliette’s whimsy enchants Roméo, and all present. The foreshadowing in the lyrics is exquisite.

“Orpheus with his lute”

Oddly enough, the fervent revival of Shakespeare in the nineteenth century continued well into the following years—as theatres continued to perform his work, it was picked up and circulated. British composers especially, such as Roger Quilter, Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Benjamin Britten, among others, sought to honour and redefine their nation’s artistic heritage in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) was influenced heavily by Tudor music and brought elements of English folk song into his operas, ballets, religious music, and symphonies. “Orpheus with his lute” is an example of a neo-classical (twentieth century interpretations of Classical or eighteenth century compositional styles) reimagining of Patience’s song from Act III scene I of Henry VIII. The 1901 score is the first of two settings by Williams of the same text.

“Falling in love with love” from Boys from Syracuse

Boys from Syracuse is a 1938 musical by Richard Rodgers (1902-1979) and Lorenz Hart (1895-1943) with book by George Abbott (1887-1995) based on A Comedy of Errors. Adriana sings this tune in Act I, while recanting the stories of her romance with her husband to her sewing circle. Love, although promising, isn’t always as it seems. Rodgers used the dance form, the waltz in particular, to set the ‘mood’ of romance and anticipatory or longing emotions. In the age of Musical Theatre composition, the use of these subliminal musical association works to create further drama and ironic or comedic juxtaposition.

The collaboration between Rodgers and Hart was short-lived, and the pair had a falling out—not romantically, but the song holds as a testament perhaps not only to Adriana’s woes, but too their professional relationship.

“The Star Crossed Lovers”(“Pretty Girl”)

“Star Crossed Lovers” is a track on the album Such Sweet Thunder by Duke Ellington and his orchestra, released by Columbia records in 1957. The album is a twelve-part instrumental suite based on Shakespeare’s works, inspired by a visit to a Festival happening at the same time as their Stratford, Ontario performance by the band leader, Duke Ellington (1899-1974), and his arranger, Billy Strayhorn (1915-1967). The album was written in three weeks and performed the next year at the festival.

Interestingly enough, aside from the Morley piece, this is the only selection on the recital that doesn’t necessitate or originate from a gendered performance; rather, it can be interpreted by any singer, as long as it is addressed to the subject of the ballad, “pretty girl”. Strayhorn was an out member of the LGBTQ+ community, and in a small effort to display how not only musical styles but also social ideas changed, I wanted to include it (and this interpretation) on the program.

For full bibliographic references, or to see the project at large, visit symphonicshakespeare.tumblr.com

#soprano#recital#ever fixed mark#shakespeare#program notes#senior recital#music school#Billy strayhorn#duke ellington#star crossed lovers#pretty girl#falling in love with love#musicology#music history

0 notes

Text

The Food of Love

"If music be the food of love, play on..."

I have to admit, I’m grateful NaBloPoMo ended when it did, because I have a choir concert this weekend and have been in rehearsals every damn night. Which is fun and rewarding and worth it and all, but is not the kind of schedule that lends itself to blogging.

And yet, the Will4Will habit is one that I don’t entirely wish to break. So, below the jump, a few performances of

(more…)

View On WordPress

#Barenaked Ladies#Derrick Morgan#Henry Heveningham#Henry Purcell#if music be the food of love#Tom Hiddleston#Twelfth Night

0 notes

Quote

If music be the food of love, sing on till I am fill'd with joy; for then my list'ning soul you move with pleasures that can never cloy, your eyes, your mien, your tongue declare that you are music ev'rywhere. Pleasures invade both eye and ear, so fierce the transports are, they wound, and all my senses feasted are, tho' yet the treat is only sound. Sure I must perish by our charms, unless you save me in your arms.

If Music Be the Food of Love, Henry Heveningham

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

If music be the food of love, music by Henry Purcell, words by Henry Heveningham. (Mandy and more opera. Whoot.)

#if music be the food of love#henry purcell#henry heveningham#opera#classical#singing#vocals#piano#recital#gpoy

4 notes

·

View notes