#Gulf Oil India

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

How to Choose the Best Engine Oil for Your Bike | Expert Guide

When choosing the best engine oil for your bike, consider these five expert tips:

1. Consult your owner’s manual for manufacturer recommendations. 2. Understand and prioritize SAE viscosity grades. 3. Evaluate the benefits of synthetic versus conventional oils. 4. Explore reputable brands like Gulf Oil India. 5. Factor in your bike’s specific requirements and riding conditions.

The right oil selection, aligned with these considerations, is paramount for optimal bike performance, reducing wear, and ensuring the longevity of critical engine components. Make an informed choice to safeguard your bike’s engine and enhance your overall riding experience.

To know more, visit — https://india.gulfoilltd.com/blog/how-to-choose-the-best-engine-oil-for-bike

0 notes

Text

How to Choose the Best Engine Oil for Your Bike | Expert Guide

When choosing the best engine oil for your bike, consider these five expert tips:

1. Consult your owner’s manual for manufacturer recommendations. 2. Understand and prioritize SAE viscosity grades. 3. Evaluate the benefits of synthetic versus conventional oils. 4. Explore reputable brands like Gulf Oil India. 5. Factor in your bike’s specific requirements and riding conditions.

The right oil selection, aligned with these considerations, is paramount for optimal bike performance, reducing wear, and ensuring the longevity of critical engine components. Make an informed choice to safeguard your bike’s engine and enhance your overall riding experience.

To know more, visit — https://india.gulfoilltd.com/blog/how-to-choose-the-best-engine-oil-for-bike

0 notes

Text

Submitted via Google Form:

What would happen to the richest countries in the world these days because they export oil when my story takes place in 2400 and and the oil is all gone and these countries are where my story actually takes place. Where all the money is now is pretty much the countries that produce cutting edge technology.

Licorice: 2400 CE is 376 years in the future.

Which countries were the richest 376 years ago? That would take us back to 1648. The richest country in the world was China, with India not far behind. The Ottoman Empire was another superpower, and most of today’s Middle Eastern oil states were its posessions. The USA didn’t even exist. The British had barely begun building their empire; the Netherlands and France were both far richer and more powerful than GB, but the European powerhouse was Spain with its Latin American colonial empire pumping out seemingly inexhaustible supplies of silver and gold bullion, inspiring a golden age of piracy in the Caribbean.

China, India, France: their wealth was based mostly on strong diverse domestic economies.

Britain, Portugal and the Netherlands: they were too small and poor to build a China-type self-sufficient diverse economy. They grew rich on trade.

Ottoman Empire: a multicultural melting pot covering roughly the same geographic area as the Eastern Roman Empire, the Ottomans had it all. But they fell behind in the 19th century, and the empire was torn apart by the waves of nationalism that swept across the globe after the French Revolution. The Ottoman Empire no longer exists.

Spain grew rich in the same way the oil economies grew rich, by mining a single commodity and using it to pay for everything

A country like the USA is going to be as fine as anywhere can be after the oil is gone. Like China, India and the EU they will diversify into renewable resources and keep right on truckin’ because their economies are sufficiently wealthy and diverse, their population sufficiently educated, and their governments sufficiently forward thinking to do this.

Back in the 18th century, the measly little island of Britain took the wealth it earned from trade to invest in R&D, invented the industrial revolution, and used its tech advantage to conquer an empire the likes of which had never hitherto been seen.

Spain, on the other hand, didn’t invest in itself. The gold and silver from the Spanish Main trickled through its fingers the way easy money always does with lottery winners. Much of the bullion ended up in China via British, Dutch, and Portuguese ships. Spain’s empire disintegrated in the 19th century.

In short, if you’re a country with a booming economy dependent on a single non-renewable commodity, and you are smart, you will use that wealth to build your competitive advantage in diverse areas of human economic activity. You will educate your population to be creative and entrepreneurial. This is more likely to happen if your government is some flavour of democracy.

If you’re not smart or if your government is controlled by a small clique of aristocrats or a dictator and his court with no accountability to the future, your elite will simply take most of the wealth for themselves, stick it into Swiss bank accounts, and leave the country impoverished and under-developed when they flee the inevitable coup.

Since the history of the years 2024-2400 hasn’t yet been written, it’s up to you to decide what the countries in your story are going to do. All of them are well aware that the oil bonanza will not last forever. You might find this useful: “How the Gulf Region is Planning for Life After Oil”.

So, which of your countries will be smart and which will be foolish? Which ones will have the foresight to build a viable post-oil future for themselves, and which ones will slide backwards into poverty, ignorance, and oppression? You decide.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gulf migration is not just a major phenomenon in Kerala; north Indian states also see massive migration to the Gulf. Uttar Pradesh and Bihar accounted for the biggest share (30% and 15%) of all Indian workers migrating to GCC1 countries in 2016-17 (Khan 2023)—a trend which continues today. Remittances from the Gulf have brought about significant growth in Bihar’s economy (Khan 2023)—as part of a migrant’s family, I have observed a tangible shift in the quality of life, education, houses, and so on, in Siwan. In Bihar, three districts—Siwan, Gopalganj, and Chapra—send the majority of Gulf migrants from the state, mostly for manual labor (Khan 2023). Bihar also sees internal migration of daily wagers to Delhi, Bombay, and other parts of India. Gulf migration from India’s northern regions, like elsewhere in India, began after the oil boom in the 1970s. Before this time, migration was limited to a few places such as Assam, Calcutta, Bokaro, and Barauni—my own grandfather worked in the Bokaro steel factory.

Despite the role of Gulf migration and internal migration in north Indian regions, we see a representational void in popular culture. Bollywood films on migration largely use rural settings, focussing on people who work in the USA, Europe, or Canada. The narratives centre these migrants’ love for the land and use dialogue such as ‘mitti ki khusbu‘ (fragrance of homeland). Few Bollywood films, like Dor and Silvat, portray internal migration and Gulf migration. While Bollywood films frequently centre diasporic experiences such as Gujaratis in the USA and Punjabis in Canada, they fail in portraying Bihari migrants, be they indentured labourers in the diaspora, daily wagers in Bengal, or Gulf migrants. The regional Bhojpuri film industry fares no better in this regard. ‘A good chunk of the budget is spent on songs since Bhojpuri songs have an even larger viewership that goes beyond the Bhojpuri-speaking public’, notes Ahmed (2022), marking a context where there is little purchase for Gulf migration to be used as a reference to narrate human stories of longing, sacrifice, and family.

One reason for this biased representation of migration is that we see ‘migration’ as a monolith. In academic discourse, too, migration is often depicted as a commonplace phenomenon, but I believe it is crucial to make nuanced distinctions in the usage of the terms ‘migration’ and ‘migrant’. The term ‘migration’ is a broad umbrella term that may oversimplify the diverse experiences within this category. My specific concern is about Gulf migrants, as their migration often occurs under challenging circumstances. For individuals from my region, heading to the Gulf is typically a last resort. This kind of migration leads to many difficulties, especially when it distances migrants from their family for much of their lifetime. The term ‘migration’, therefore, inadequately captures the profound differences between, for instance, migrating to the USA for educational purposes and migrating to the Gulf for labour jobs. Bihar has a rich history of migration, dating back to the era of indentured labor known as girmitiya. Following the abolition of slavery in 1883, colonial powers engaged in the recruitment of laborers for their other colonies through agreements (Jha 2019). Girmitiya distinguishes itself from the migration. People who are going to the Arabian Gulf as blue-collar labourers are also called ‘Gulf migrants’—a term that erases how their conditions are very close to slavery. This is why, as a son who rarely saw his father, I prefer to call myself a ‘victim of migration’ rather than just a ‘part of migration’. It is this sense of victimhood and lack of control over one’s life that I saw missing in Bollywood and Bhojpuri cinema.

— Watching 'Malabari Films' in Bihar: Gulf Migration and Transregional Connections

#bhojpuri indentured history#malayalam cinema#bihari labour migration#gulf migrant labour#malayali labour migration#bollywood cinema#bhojpuri cinema#nehal ahmed

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Red Sea might just be history’s most contested body of water. It has been the site of imperial or great-power competition for at least 500 years, from the Portuguese search for the sea route to Asia all the way to the Cold War. It remains the most important trade link between Asia and Europe. The Suez Canal at its northern egress has been displaced by the Singapore Strait as the world’s most important chokepoint, but it’s still the second-most vital; 30 percent of global container ship traffic moves through that canal. Container ships are to globalization what eighteen-wheelers are to the United States—the workhorses of trade. And there are important energy flows here: 7.1 million barrels of oil and 4.5 billion cubic feet of natural gas transit the Bab el-Mandeb (the southern entrance to the Red Sea) every day, per the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

So attacks by Houthi forces on “Israeli” shipping in recent days have the potential for major disruption. “Israeli” is in quotes because commercial shipping ownership is complicated and opaque: Ship ownership, ship operation, and flag of registry often differ, and none necessarily has any bearing on the ownership or destination of the cargo on board or the nationality of the crew. What’s more, Houthi attacks have quickly morphed from semi-targeted at ships nominally linked to Israel to more indiscriminate. The world’s most important container shipping firms—including MSC, Maersk, Hapag-Lloyd, and Cosco—have paused on sending ships through these waters for fear of loss of life or damage.

Enter a new U.S.-led task force with the somewhat on-the-nose moniker Operation Prosperity Guardian, a naval coalition to protect commercial shipping from Houthi attacks. It will operate under the aegis of a preexisting mechanism, the Combined Maritime Forces, a counterpiracy and counterterrorism naval coalition (the world’s largest, by far) that operates out of Bahrain. So far, nine countries have signed up officially (though some with very modest contributions—Canada, for example, is sending three staff officers and no ships yet); there are reports that others have quietly agreed to participate or contribute. India, which has a lot at stake here (especially in the disproportionate number of Indian nationals among the crews of major commercial lines), is not part of the coalition but is independently contributing two vessels to the effort.

The United States and France have long had bases in Djibouti to project power across the Red Sea, recently joined by Japan and China, and the European Union operates out of the French base to support Operation Atalanta, a counterpiracy task force that protects trade in the nearby Gulf of Aden (alongside the U.S.-led Combined Task Force 151, which has the same mission). But this skirmish is an astonishingly asymmetric fight. With a handful of missiles and drones, the Houthis have succeeded in placing at risk one of the most important arteries of the global economy.

The asymmetry has caused some of the debate to focus on the cost of the drones versus the cost of the missiles being used to defend the ships. It’s the wrong metric. The right calculation is cost of the missile versus cost of the target. If a drone attack succeeds, it could wreck a ship worth anywhere upwards of $50 million and carrying trade goods likely in the $500 million range—and in some cases, roughly double those amounts.

The real problem of volume is a different one. The primary ships being used for these operations—for the United States, Arleigh Burke-class destroyers; for the United Kingdom, the Daring class—sail with an arsenal of roughly 60 missiles that are useful for shooting down drones or missiles. (They carry other types of missiles as well, rounding out the complement of armaments, but not ones germane to this fight.) At the pace at which the Houthis have been conducting attacks, a single ship would expend its relevant armaments in a couple of weeks and need to be rotated out; there’s no way to replenish these missiles at sea. If the Houthis keep up the pace of attacks and have a steady supply of drones and missiles (which seems likely), the cost of maintaining a naval escort operation—including the costs of operating the ships at distance—will rapidly rise into the tens of billions of dollars.

The West faces three options, all with serious downsides.

First, reroute the shipping. For now, until the task force is assembled, shippers are switching routes between the Red Sea and the long voyage around the Cape of Good Hope off southern Africa. It’s been done before, when the Suez Canal was closed as a result of Arab-Israeli wars in the late 1960s and early ’70s. But global trade then was a fraction of global trade now. Rerouting via the Cape of Good Hope would add roughly 60 percent of the transit time (and fuel cost) from Asian ports to European ones, not just adding costs to shippers (who would pass those costs onto consumers) but more importantly gumming up the works in global just-in-time manufacturing. While this is an acceptable option for a week or two, any longer and the disruption to global sea-based supply chains would be significant.

Second, attack the missiles and drones at the source, either to eradicate the armaments or deter the attacks. Already there’s a drumbeat of criticism that U.S. President Joe Biden hasn’t yet authorized this course. Easily said but less easily achieved. It would not be too hard for Houthi forces to hide both themselves and a stockpile of drones and missiles from U.S. targeting, so any attacks—from two U.S. carrier strike groups in nearby waters—would have to be pretty wide-ranging and even then are likely to miss pockets of weaponry. Would Iran—the Houthis’ primary backers—be thus deterred? It’s unclear how or why; Iran is surely willing to allow the Houthis to sustain substantial casualties for the “win” of harassing “the West” in the Red Sea. Attacking Iran itself is the next logical step and may prove necessary, but that carries its own major risk of escalation while Israel is grappling with the missile threat from Hezbollah on its northern border with Lebanon.

Third, widen the coalition. So far, Germany has not joined in, to some criticism but with good reason. There are mounting demands on Germany’s modest navy in Northern European waters, where the Russians are flexing their subsea muscles. Australia was asked to join but made the counterargument that its modest naval capacity is better deployed in the Western Pacific. Japan could contribute, especially since it has a base in Djibouti. Another potential contributor is China, which has a base nearby and a long track record of contributing to counterpiracy operations in the Indian Ocean. There’s a dilemma here for the West, though: Do the Western powers prefer to (a) pay the price of protecting global sea-based trade, of which China is the largest source and arguably primary beneficiary, or (b) help facilitate China’s growing capacity to project naval power across the high seas?

The entire episode highlights this point: There’s a deepening contradiction between the reality of globalization, heavily dependent on sea-based trade and on China, and the reality of geopolitical contest, in which naval power is rapidly emerging as a central dimension. Tensions and bad choices abound in the Red Sea—but they are also a harbinger of tougher choices and turbulent waters ahead.

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

What factions do you headcanon exist post-Tragedy? There's the Future Foundation, Towa City, and the various Despairs, but I don't see anything else about how societies exists in the DanganRonpa-verse, especially with their whole fascination on the semi-supernatural Talent that sorta caused the Tragedy in the first place.

I don’t have exact factions (Mainly because I was a child in 2012, the year THH takes place), but I do have general ideas of what might some factions look like, and what generally said cliques that rose from the collapse would act towards junko. Also headcanons for how some areas might collapse and redevelop.

1.Islamists would be very present in the Middle East. That era was around the peak of ISIS, and I think the tragedy increasing radicalization would only make that worse. Speaking of religious radicalization….

2. The American right-wing “tea party” faction, would be a heavy presence in the former United States. Their cliques would vary from corporatism to outright religious theocracies. Heck, junko’s influence could’ve fanned their flames into facism, being the way the union collapsed in this timeline, akin to the US today.

3. The absolute monarchies collapse. All of them are prevalent on a central figure, ones that I have no doubt Junko would get their entire lines killed to force conflict. This would be a definite way to get an opening through infighting in Saudi Arabia and the gulf states. This also applies to NK and similar regimes.

4.Africa’s borders would be nearly completely redrawn. With the primary motivation for the borders being nobody wanting to move colonial borders, the collapse of Europe would make these borders obsolete. Whatever ethnic tension came up would fracture the post colonial states not only de jure, but de facto.

5.Any multiethnic states are almost completely rended apart. Whether it be one breakaway, or outright collapse, nations like Indonesia, Malaysia, and India would face ethnic violence.

6.Everyone gets a trade shock. The entire model of globalism in the 2010’s would be the equivalent of MAD, one junko would exploit. States like the oil states and Singapore would be hit the hardest, while states with notable sanctions (Iran,Cuba) would ironically be spared from this, although their governments would go through some things.

7.The states aligned with despair have levels in how bad they are. You have cliques who allied with despair out of convenience, and you have 77-B controlled states like Novoselic. Their brutality would vary between, although still be bad, considering the worldwide warlord era. When junko died, many of the less extreme cliques would either have their leaders commit suicide, turned to her side fully, and have less extreme people take over, or outright purge their despairite influence best they could. These states would be accepted back into the world community, to the FF chagrin.

8.There would be a notable split after everything settled somewhat. The FF would face heavy opposition from a myriad of groups, the most notable most likely being of some leftist variety, considering the oligarchic and unequal ideas of innate talent. I could see the FF contesting the very archipelago of Japan with the Japanese Communist Party. Even after post-DR3, where Makoto would definitely want to reconcile with the left, they wouldn’t be very trusting of the FF’s intentions.

9. A ton of city states. Whether they split off from a greater entity, or were forcefully ejected like Singapore, I’d expect for a lot of nations to fracture down to the city at some places.

10.And as my last one, it’s more about how the tragedy (or collapse, as it would probably be known) would be viewed. I’d say the Arab spring would be inherently tied to it, due to similar ways of organizing and wanting to overthrow established regimes. Heck, I could see more reactionary people arguing that the collapse did not begin with the tragedy, but the popular overthrow of the government of Tunisia.

Again, these are just my thoughts on the whole thing, so it’s really up to you.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

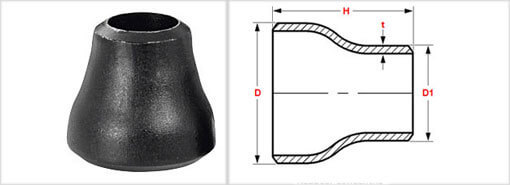

Concentric Reducers Exporters in India

CONCENTRIC REDUCERS

The Concentric Reducers are accessible in assortment of shapes and measurements to suit real pipeline establishment necessities in commercial ventures. This is a standout amongst the most generally utilized modern funnel fitting for adjusting distinctive channel sizes in a pipeline framework. It is fundamentally used to associate two funnels with various widths.

Produced using best grades of stainless steel, these reducers are accessible in an extensive variety of sizes, divider thicknesses and weight evaluations to look over as indicated by the pipeline. Guaranteeing an in-line funnel shaped move between various widths of pressurized channels, these concentric reducers join the pipelines on the same axis.The development of these reducers is finished by joining the little breadths and expansive distances across on inverse closures of cone formed move area. Discover application in petrochemicals, sugar factories and refineries, steel plants and bond and development commercial ventures, the reducer has separate gulf and outlet closes.TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONSSTANDARD MATERIAL GRADES OF BUTTWELD SS REDUCER

Stainless steel grades:

ASTM A403 Grade WP304, WP304L, WP304H, WP304N, WP304LN, WP309, WP310S, WPS31254, WP316, WP316L, WP316H, WP316N, WP316LN, WP317, WP317L, WP321H, WP321, ASTM A815 S31803, S32750, S32760, S32205

Standard material grades in stainless steel:

ASTM A182 F304, F304H, F304L, F304N, F304LN, F309H, F310, F310H, F316, F316H, F316L, F316N, F316LN, F317, F317L, F347, F347H, F321, F321H, FXM-19, F50, F51, F53, F55, F60, F904L

Application Areas:

Oil and gas industry

Petrochemical industry

Power stations

Shipbuilding industry

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

U.S. will send F-16 fighters to the Gulf region to protect ships from Iranian seizures

The U.S. action comes after Iran tried to seize two oil tankers near the strait last week, setting fire to one of them.

Fernando Valduga By Fernando Valduga 16/07/2023 - 15:49in Military, War Zones

The U.S. is reinforcing the use of fighters around the strategic Strait of Hormuz to protect ships from Iranian seizures.

Speaking to Pentagon reporters, a senior defense official told reporters on Friday that the U.S. will send F-16 fighters to the Gulf region to increase the A-10 attack aircraft that have been patrolling there for more than a week, according to the Associated Press.

The official also said that the U.S. is increasingly concerned about the growing ties between Iran, Russia and Syria in the Middle East.

The defense officer, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said that the F-16s will give air cover to ships moving along the waterway and increase the visibility of the military in the area, as an impediment to Iran.

The U.S. action comes after Iran tried to seize two oil tankers near the strait last week, setting fire to one of them.

Officials said that in the last two years, Iran has persecuted, attacked or interfered in the navigation rights of 15 international-flagged commercial vessels.

At the end of April, Iran seized the Marshall Islands flagd Advantage Sweet while traveling in the Gulf of Oman. Six days later, he seized a second ship, the Niovi, a tanker with the flag of Panama when leaving a dry dock in Dubai.

The Strait of Hormuz, a crucial waterway for the global supply of energy, is usually a place of tense encounters between Americans and Iranian forces.

In early December, an Iranian patrol boat tried to temporarily blind U.S. Navy ships in the Strait of Hormuz, pointing a spotlight at the ships and crossing them 150 meters from them.

Last August, an Iranian ship seized an American unmanned military research ship in the Gulf, but released it after a patrol boat and a U.S. Navy helicopter were sent to the scene.

Tags: Military AviationF-16 Fighting FalconUSAF - United States Air Force / U.S. Air ForceWar Zones - Iran

Sharing

tweet

Fernando Valduga

Fernando Valduga

Aviation photographer and pilot since 1992, has participated in several events and air operations, such as Cruzex, AirVenture, Daytona Airshow and FIDAE. He has works published in specialized aviation magazines in Brazil and abroad. Uses Canon equipment during his photographic work around the world of aviation.

Related news

AIR SHOWS

RIAT 2023: Messerschmitt Me 262 makes its debut at the largest military air show in England

16/07/2023 - 18:33

MILITARY

Ten design features that will shape the USAF's next-generation air domain program

16/07/2023 - 18:04

Indian Air Force LCA Tejas.

MILITARY

India and France announce co-development of combat jet engines

16/07/2023 - 14:04

MILITARY

US considers military options against Russia for "complicating" anti-ISIS efforts in Syria

16/07/2023 - 12:10

MILITARY

New Zealand completes its fleet of P-8 Poseidon

15/07/2023 - 17:38

MILITARY

Decision of the next Swedish fighter is still several years away

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Istg some of you use “eurocentrism” to mean “I don’t care about anything that doesn’t immediately affect me” because for damn sure you guys are not lifting up the voices of EVERY SINGLE CLIMATE ZONE CHANGE

Bruh, I live in Louisiana, we’ve had….flecks of ice once every ten years? Maybe? So yeah that’s not gonna be noticeable or different, but it IS less cold even to me in the winter and takes longer to get cold, and it is DEFINITELY HOTTER. Like, DANGEROUSLY FUCKOFF HOTTER in the summer, it’s entirely possible that due to the wet bulb effect this area may be UNSAFE without air conditioning in the near future, if it isn’t already. I know people in India and Mexico are already dying from summer wet bulb heat waves without air conditioning! People were posting about that last summer?! I was reblogging it?!

And oh, on the topic of self-interest…..lol. Lmao. Each climate zone has been having its own climate tragedies that you’re assuming people aren’t paying attention to because what, they’re talking about snow? How do you know? Were you following all these people and what they were posting? Have YOU been paying attention to the various climate disasters in various climate zones? Why the assumed bad faith for others but not yourself? Like, I get the annoyance at the previous “Hurf durf air conditioning is wasteful, everyone should give it up because climate change, people only die from freezing to death, just wear less clothes and drink more water” and like READ ABOUT WET BULB EFFECT YOU IGNORANT SLUT, PEOPLE ARE DYING. But this? Is not that. The unusual droughts and floods in the Midwest? The back to back to BACK once-in-lifetime severity hurricanes hitting the Gulf Coast?(‘They get those all the time, they’re used to it’ LOL NOT CATEGORY 4 EVERY OTHER YEAR, not hitting Lake Charles so damn often and hard you would think it’s Sodom and they can’t even recover and rebuild from the last one and people just have permanent blue tarps on their roof, not hurricanes randomly rerouting all the way up to New York and all we can think is “at least it’s not us for once”

This flippant “psst I never had snow” is missing the point entirely. If you haven’t noticed some sort of change to your climate environment, then you’re either too young, very unobservant, or don’t WANT to see it. My area’s economy RUNS on oil and gas, and it’s so obvious now that it’s the constant elephant in the room, the devil’s bargain we made that we dare not speak about because it’s frankly too depressing. It’s COMING for you, it’s just a question of how and how fast.

Christmas as a cultural icon is starting to get really dystopian in a climate sense, december has historically been a time of year in which there would be snow in a significant portion of europe and north america, and the fact that its not even icy this time of year and all the christmas songs and decorations reference a time of year that will likely never exist in the same way again in my life time is so strange.

116K notes

·

View notes

Text

Deepwater and Ultra-Deepwater Drilling: Trends, Growth, and Future Outlook

Introduction

Deepwater and ultra-deepwater drilling have become increasingly important in the global energy landscape. As traditional onshore reserves continue to decline, oil and gas companies are turning to offshore reserves located at extreme depths. These drilling technologies allow access to previously untapped hydrocarbon reserves, offering a promising solution to meet growing global energy demands.

In the forecast period of 2025 to 2034, the global deepwater and ultra-deepwater drilling market is projected to grow at a CAGR of 9.00%, reflecting significant industry investments, technological advancements, and expanding exploration activities.

Market Overview and Drivers

The offshore drilling sector, especially in deep and ultra-deep waters, is expanding rapidly due to growing global energy demand, particularly in regions like Asia-Pacific, Africa, and Latin America. While renewables are on the rise, oil and gas remain essential for industrial operations and transportation. As onshore reserves decline, energy companies are turning to offshore basins such as those in Brazil and West Africa for new opportunities. Technological advancements—like dynamic positioning systems, ROVs, and seismic imaging—have made deepwater drilling safer and more cost-effective. Additionally, countries rich in offshore resources are offering favorable policies and licensing rounds to attract foreign investment and boost economic growth.

Take advantage of a free, no-obligation sample report - View Here

Key Market Trends

Adoption of Floating Production Systems - Floating Production Storage and Offloading (FPSO) units are revolutionizing offshore production, allowing oil companies to process and store crude oil directly at the extraction site. These systems are particularly vital for ultra-deepwater fields located far from coastal infrastructure.

Shift Towards Sustainable Drilling - Many offshore drilling operators are integrating ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) practices by reducing carbon footprints, enhancing safety standards, and adopting clean technologies such as electrified rigs and hybrid platforms powered by offshore wind.

Growing Role of Digitalization - Predictive maintenance, real-time monitoring, and AI-driven drilling optimization are becoming common in offshore operations. These digital tools reduce downtime, increase productivity, and improve asset longevity, especially in high-risk deepwater environments.

Regional Insights

Latin America - Brazil remains a global leader in ultra-deepwater drilling, thanks to its prolific pre-salt fields. Investments from global giants like Petrobras, Shell, and TotalEnergies continue to support the region's offshore dominance.

Africa - West Africa, particularly Nigeria and Angola, is emerging as a significant ultra-deepwater hub. New discoveries and governmental reforms are fueling increased offshore activities.

North America - The Gulf of Mexico is one of the most mature offshore regions. Despite environmental scrutiny, it remains a vital part of the U.S. energy mix, with consistent investment in deepwater assets.

Asia-Pacific - Countries such as India, Malaysia, and Indonesia are exploring ultra-deepwater blocks to enhance energy security and reduce dependence on imports.

Challenges Facing the Industry

High Capital Requirements - Deepwater projects often require initial investments in the billions, making them viable primarily for major oil companies with access to long-term financing and risk management strategies.

Environmental and Safety Risks - The 2010 Deepwater Horizon spill highlighted the environmental risks associated with deepwater drilling. Stringent regulations now require advanced safety mechanisms, extensive training, and real-time emergency response systems.

Market Volatility - Oil price fluctuations significantly affect offshore drilling investments. Sustained low prices can delay or cancel planned projects, particularly those in the early exploration phase.

Skilled Labor Shortage - Operating at ultra-deepwater levels requires highly specialized skills. The industry is currently facing a shortage of qualified professionals in fields like subsea engineering, digital analytics, and remote operations.

Future Outlook

Despite challenges, the outlook for deepwater and ultra-deepwater drilling remains positive. As energy demand continues to rise and technology makes offshore operations more efficient and cost-effective, exploration at extreme depths will play an increasingly vital role in the global energy portfolio.

In addition, the integration of digital twins, autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), and advanced carbon capture technologies is expected to further enhance safety, efficiency, and sustainability.

Deepwater and ultra-deepwater drilling represent the next frontier of oil and gas exploration. With proven reserves, advanced technologies, and rising demand, the sector is poised for robust growth over the next decade. The key to success will be balancing profitability with safety, sustainability, and adaptability in a rapidly evolving energy landscape.

As the world navigates its transition to low-carbon energy sources, deepwater drilling will remain a strategic pillar—bridging the gap between current energy needs and the renewable future.

Media Contact

Company Name: Claight Corporation Email: [email protected] Toll Free Number: US +1-415-325-5166 | UK +44-702-402-5790 Address: 30 North Gould Street, Sheridan, WY 82801, USA Website: www.expertmarketresearch.com

#Deepwater and ultra-deepwater drilling#Deepwater drilling market trends#Offshore oil and gas exploration#Deepwater drilling rigs

0 notes

Text

What is the G20 doing??????

Global Update – The energy crisis stemming from the devastated Middle Eastern oil industry is now triggering power outages in several G20 nations. South Korea, India, Japan, Germany, and Turkey are reportedly among those experiencing significant energy disruptions. These countries, heavily reliant on oil imports from the Gulf region, are facing immediate consequences as supplies are critically impacted by the ongoing disaster. This is the direct effect of their lack of action. An instagram influencer “Baby Gronk” has released a viral video calling these G20 countries out for their inaction.“What good is the G20’s emergency meeting if they are unable to get anything done? What good is being in the top 20 countries and meeting if all they do is lip service and debate endlessly. This must end immediately else there will be no more world for Livvy Dunne and I to live in”

0 notes

Text

Explore Gulf Careers with the Best Recruitment Agency for Bahrain in Pakistan

For thousands of skilled and semi-skilled Pakistani workers, Gulf countries like Bahrain present an ideal destination for overseas employment. With attractive salaries, tax-free income, modern infrastructure, and a strong demand for manpower across multiple sectors, Bahrain has become a gateway for career development and financial stability. However, finding the right opportunity in a foreign land requires more than just ambition it requires the right recruitment partner. Falisha Manpower, proudly recognized among the #1 Manpower Recruitment Agencies In Pakistan, bridges the gap between Pakistani talent and Bahraini employers. As a reliable and efficient Recruitment Agency For Bahrain in Pakistan, Falisha Manpower is committed to making overseas employment easy, transparent, and successful.

Why Bahrain is an Ideal Job Destination for Pakistanis

Bahrain, a member of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), has emerged as a major hub for foreign workers from Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, and other countries. There are several reasons why Pakistani workers choose Bahrain as their preferred overseas employment destination:

1. Booming Sectors and Job Availability

Bahrain’s economy is rapidly expanding, particularly in sectors like:

Construction and Infrastructure

Oil and Gas

Hospitality and Tourism

Security Services

Health and Medical Services

Logistics and Transportation

IT and Telecommunications

This growth fuels a continuous demand for both skilled and unskilled manpower.

2. Attractive Compensation and Work Benefits

Bahrain offers tax-free salaries, accommodation, medical coverage, transport allowances, and end-of-service benefits, making it financially rewarding for Pakistani workers.

3. Cultural Compatibility and Ease of Adaptation

The presence of a large Pakistani expatriate community and the shared Islamic culture make it easier for Pakistanis to adjust and thrive in Bahrain.

The Need for a Reliable Recruitment Partner

While opportunities abound in Bahrain, many Pakistani job seekers fall into the trap of fraudulent agents or unlicensed consultancies. Fake job offers, hidden charges, and visa scams are common risks in overseas job placement.

This highlights the importance of working with a licensed and experienced Recruitment Agency For Bahrain in Pakistan—an agency that operates with integrity, ensures legal compliance, and maintains a transparent process from job application to final deployment.

That’s exactly what Falisha Manpower delivers.

Pakistan’s Trusted Bridge to Bahraini Employers

Falisha Manpower is more than just a recruiting agency it is a trusted partner in building careers abroad. As one of the #1 Manpower Recruitment Agencies In Pakistan, Falisha Manpower holds official licenses and approvals from the Government of Pakistan and works in close coordination with Bahraini ministries and employers.

Its core mission is to simplify the overseas hiring process for candidates and ensure they secure safe, legal, and rewarding employment in Bahrain.

What Makes Falisha Manpower the Best Recruitment Agency for Bahrain?

1. Access to Verified Bahraini Employers

Falisha Manpower maintains strong partnerships with reputed companies and employers in Bahrain. Each job offer is thoroughly verified for authenticity and compliance with Bahraini labor laws.

This protects candidates from job scams and ensures they land positions that match their qualifications and expectations.

2. Industry-Specific Job Opportunities

Whether you are an engineer, electrician, driver, cleaner, cook, nurse, or IT professional, Falisha Manpower offers a wide range of job roles in sectors such as:

Civil & Mechanical Construction

Oil & Petrochemical Plants

Hotels & Catering Services

Medical & Paramedical Fields

Security & Safety Services

Technical and Maintenance Services

3. Transparent Recruitment Process

From candidate screening and document collection to visa processing and departure, Falisha Manpower follows a clear and honest recruitment process. No hidden fees. No false promises.

Each step is documented, and candidates are regularly updated about their status.

4. Full Visa and Documentation Support

Navigating Bahrain’s visa and employment requirements can be complex, but Falisha’s visa experts handle it seamlessly. Services include:

Document attestation

Medical test coordination

Visa stamping

Contract verification

Air ticket arrangements

Immigration clearance

5. Pre-Departure Orientation

Before departure, candidates receive orientation sessions that prepare them for cultural differences, workplace conduct, Bahraini labor rights, and general survival tips. This ensures a smoother transition abroad.

6. Post-Deployment Support

Falisha Manpower doesn’t disappear once you’re hired. Their after-deployment support ensures you're assisted in case of any on-site issues, contract clarifications, or emergencies.

The Step-by-Step Hiring Process with Falisha Manpower

Step 1: Registration

Interested candidates can register through Falisha’s website or visit their office. After registration, a recruitment consultant is assigned to each candidate.

Step 2: Interview and Screening

Candidates are evaluated based on their skills, education, and experience. Interviews may be conducted in person or virtually, depending on the employer’s preference.

Step 3: Job Offer and Contract Signing

Once selected, candidates receive an official offer letter and employment contract. All terms—salary, duties, benefits—are reviewed transparently.

Step 4: Medical and Documentation

Medical fitness is verified through approved labs. Documents are submitted for verification and sent for visa processing.

Step 5: Visa Stamping and Deployment

Once the visa is stamped, tickets are arranged, and candidates are given pre-departure briefings before traveling to Bahrain.

Why Falisha Manpower Is the #1 Choice

Falisha Manpower continues to rise above the rest because of:

Government Accreditation

Strong Industry Relationships in Bahrain

Decade-Long Experience in Overseas Placement

Dedicated Customer Service Team

High Success Rate in Visa Approvals and Placements

Ethical and Transparent Operations

These qualities position Falisha as one of the #1 Manpower Recruitment Agencies In Pakistan.

Tips for Job Seekers Aspiring to Work in Bahrain

If you’re considering applying through a Recruitment Agency For Bahrain in Pakistan, here are a few quick tips:

Only work with licensed agencies like Falisha Manpower.

Never submit original documents without proper receipts.

Avoid agents asking for upfront payment without receipts or contracts.

Make sure your employment contract is signed and stamped.

Stay informed about Bahraini labor laws and your rights as a worker.

How to Apply for Jobs in Bahrain with Falisha Manpower

Step 1: Visit Falisha Manpower's Website Step 2: Browse current job openings for Bahrain Step 3: Submit your application and documents Step 4: Get matched with a verified Bahraini employer Step 5: Receive guidance on visa, tickets, and orientation Step 6: Fly to Bahrain and start your new career

Conclusion

For Pakistanis dreaming of building a successful career in the Gulf, Bahrain offers exceptional opportunities across various industries. However, the key to unlocking these doors lies in choosing the right recruitment partner. Falisha Manpower, as a government-licensed and trusted Recruitment Agency For Bahrain in Pakistan, ensures that your overseas journey is legal, transparent, and secure. Recognized among the #1 Manpower Recruitment Agencies In Pakistan, Falisha is dedicated to turning your overseas employment dreams into reality.

0 notes

Text

It was only a matter of time before Russia’s fast-growing shadow fleet, a group of vessels whose owners do their utmost to conceal their identity while carrying oil to evade sanctions on Moscow, started becoming a serious maritime risk. Russian vessels are now regularly turning down pilotage in Danish waters, the Financial Times reports—a practice that not only breaches maritime etiquette but could also lead to a disastrous accident.

The collision involving a container ship and Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge in the United States on March 26 demonstrates the dangers involved when bulky ships vessels through difficult waters. Indeed, the Dali struck the bridge despite being steered by two pilots. Even if just a small share of vessels turn down pilotage, similar disasters risk becoming commonplace.

International maritime rules strongly recommend the use of pilots with specialized local knowledge for most vessels sailing through Denmark’s Great Belt, the narrow passage between the country’s largest islands. The Great Belt is not just narrow—it also has treacherous waters and is extremely busy: Every year, some 70,000 vessels pass through the Great Belt and the nearby Sound (Oresund), which sits between the shores of Denmark and Sweden. It’s standard practice to follow international maritime recommendations and take on an experienced local pilot when it comes to difficult navigation routes, whether that’s the Great Belt or the Suez Canal.

The Geography of the Danish Straits

For the sake of maritime order and safety, Copenhagen could block ships that refuse pilotage. That, though, might trigger a standoff with Russia—if Moscow admits its role as a patron of the shadow fleet. Indeed, blocking these rule-breaking vessels would itself violate international maritime rules. Before forcing such a choice, however, the open-source intelligence community could help by revealing the identities and whereabouts of shadow vessels’ owners.

Since the beginning of this year, at least 20 tankers that are suspected to be shadow vessels transporting Russian oil have refused to take Danish pilots on board, according to internal reports leaked to the Financial Times and the Danish research group Danwatch.

That’s at least 20 tankers that have sailed through the Baltic Sea—in most cases via the Gulf of Finland, passing through the exclusive economic zones of Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Sweden, and Germany—into Danish waters and the Great Belt, from which they have traveled on to Kattegat (comprising Danish and Swedish waters) and Skagerrak (Danish and Norwegian waters) and into the North Sea and the oceans that will bring them to their buyers in countries such as India and China.

Shadow vessels are clapped-out ships that spend their last remaining years providing transportation to and from sanctioned countries that official vessels and their owners won’t touch. The risk that these and other dark vessels pose to coastal states is further increased by the fact that they sail under the flags of countries unlikely to come to anyone’s aid if they cause accidents or incidents (Gabon is a particular favorite) and don’t undergo regular maintenance. Any accident—be it a collision or an oil leak—is likely to be doubly disastrous as a result.

Add to that the fact that their owners are hard to track down—and that they lack proper insurance. If a shadow vessel were to sustain a massive oil spill in, say, Finnish waters, Finnish authorities and taxpayers would end up on the hook. And shadow vessels are more likely than law-abiding ones to be involved in accidents since they frequently turn off their AIS (automatic identification system), a GPS-like navigation tool that allows vessels to see one another.

Since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia’s attempts—often successful—to avoid sanctions have caused the shadow fleet to balloon; it’s currently thought to encompass some 1,400 vessels, though like all illicit activities, it’s impossible to measure precisely. (My report about the shadow fleet from last December provides an in-depth examination of the ships and the threats posed by them.)

If oil spills do occur, the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) International Oil Pollution Compensation Funds assist the countries affected. But if oil and other toxic spills increase substantially, as they’re likely to do as a result of the shadow fleet, the fund won’t have enough money to compensate everyone.

So should Denmark simply block shadow vessels refusing pilotage, or all shadow vessels for that matter?

Not so fast. Yes, shadow vessels violate international maritime rules and conventions—but the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) gives all vessels the right of so-called innocent passage, meaning the right to sail through other countries’ territorial waters and exclusive economic zones. The fact that shadow vessels violate maritime rules doesn’t give coastal states the right to violate the rules in turn.

And, noted retired Rear Adm. Nils Wang—a former chief of the Danish Navy, which also covers a range of coast guard tasks—“according to international law, the Danish Straits are international straits and are not under Danish jurisdiction. For this reason, too, Denmark doesn’t have the legal right to force ships to use pilots.”

Though most ships follow the IMO’s recommendations and use pilotage, for which they pay a fee, over the years there have been some cheapskates that turned down pilotage. In some cases, those ships caused oil spills. “Every time there’s a leak from a vessel that didn’t use pilotage, there’s an outcry to ban offenders, but we can’t,” Wang said.

Then, in the mid-2010s, the number of cheapskates traveling without pilotage grew.

Danish authorities got creative and announced that if ships with drafts (the amount that the extends beneath the waterline) of more than 11 meters (about 36 feet) didn’t request pilotage, then the Danish authorities would call them on VHF, the radio used by sailors, and remind them that they weren’t following international recommendations, and that Denmark would report them to their flag state and the IMO.

What’s more, a call on VHF allows every vessel in the vicinity to hear the conversation. “And then we started doing it,” Wang said. “And it changed behavior, because it was embarrassing for the ships and the captains to be called out like this. But if you’re part of the dark fleet, you don’t give a damn. Calling these vessels out won’t make a difference.”

Coastal states do have the right to block access in their territorial waters in certain cases—such as if transiting vessels are in poor repair or lack proper insurance. But when nations agreed and signed UNCLOS in 1982, a situation in which a country systematically evades globalization-based economic sanctions by using a fleet of dark vessels was inconceivable.

In response to the emergency of the shadow fleet, the world’s UNCLOS signatories could convene to make pilotage in sensitive waters mandatory. But such negotiations would take a long time, and under the current geopolitical conditions may never reach a conclusion. And because the Danish Straits are international waters, Denmark can’t impose new rules on its own.

This is globalization in a fiercely geopolitical era: Russia can invade Ukraine and evade the resulting sanctions by means of a fleet that sails through law-abiding countries’ waters—and their governments can’t stop it. On the contrary, with Russia now having joined Iran, Venezuela, and North Korea in using a shadow fleet, more countries will conclude that misbehaving and incurring economic sanctions is no big deal. And trade using dark vessels is cheaper than using legally operating ones.

An even larger shadow fleet would, of course, increase the risks both for marine wildlife and regular shipping. If a Russian shadow vessel collides in the Danish Straits with a legal merchant vessel, or even a Danish Navy vessel, what would Denmark do? What would NATO do?

But for now, there’s one group of dark-fleet operators that can be targeted completely legally and without risk of geopolitical escalation: the shadow vessels’ owners. They are plentiful and hide behind post office box addresses in countries such as the United Arab Emirates—because they don’t want to emerge from the shadows.

On the good side in this standoff, though, we have a large and growing community of open-source investigators, both professionals and amateurs. These investigators should take on a good deed for the global maritime order and investigate shadow-vessel owners, then share their identity and activities. Some may be hardened criminals immune to the embarrassment of public scrutiny, but many others may simply be ordinary businesspeople who have spotted an opportunity.

Just as with the ships once called out on Danish radio, public shame may be one way to force people to act for the better.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Pollachi Coconut is the Tastiest in the World ?

When you break open a Pollachi coconut, it’s like unlocking a piece of tropical heaven. The sweetness, the fresh aroma, and the soft, white flesh are unmatched. But what makes these coconuts so special? It's not just nature—it’s love, tradition, and the soul of Pollachi itself. Let's dive deep into the story of the tastiest coconut on Earth.

The Heart of Pollachi – Nature's Coconut Paradise

Pollachi, a beautiful town in Tamil Nadu, India, is surrounded by the lush Western Ghats. This region is more than just picturesque—it’s a natural cradle for coconut farming. The climate here is warm and humid, and the soil is rich and red, filled with nutrients. These perfect conditions help create coconuts that are sweeter, creamier, and more flavorful than those from anywhere else.

The Secret Behind Pollachi Coconut's Taste

Rich Red Soil: The mineral-packed red soil boosts coconut tree health and flavor.

Pure Water: Coconuts here are nurtured with groundwater from the Western Ghats, known for its purity.

Traditional Farming: Local farmers still use age-old organic practices passed down through generations.

Ideal Climate: The consistent tropical weather makes coconuts mature evenly with natural sweetness.

My Story – A Life Surrounded by Coconuts

Growing up in Pollachi, coconuts weren’t just food—they were family. I still remember my grandfather waking up early, blessing the trees before harvest. We’d all gather to help, barefoot in the cool soil, laughing as we loaded the fresh coconuts onto bullock carts. That deep care and connection with the land—that’s what you taste in every Pollachi coconut.

Loved Across the World

Today, Pollachi coconuts travel far and wide—to the USA, the UK, and Gulf countries. Whether it’s tender coconut water enjoyed on a hot day or thick coconut milk used in curries, chefs and families around the world prefer Pollachi coconuts for their natural sweetness and aroma.

Perfect for Every Use

Tender Coconuts: Naturally sweet, hydrating, and perfect for drinking.

Mature Coconuts: Rich white flesh ideal for cooking or making coconut milk.

Dry Coconuts (Copra): High in oil content, perfect for premium coconut oil extraction.

Our Commitment at Pollachi Farmers Market

At Pollachi Farmers Market, we are not just exporters—we are storytellers, dreamers, and protectors of tradition. Every coconut we export is handpicked with love. Our farmers are part of our family, and every harvest is a celebration of their hard work. We ensure only the finest coconuts make their way to your home—fresh, flavorful, and full of soul.

Why People Can’t Get Enough

Customers across the globe often tell us how our coconuts remind them of home, of childhood, of simpler times. Some say their kids, who refused to drink coconut water before, now ask for “Pollachi coconut” by name. That’s the power of authenticity and emotion in every nut we send.

How to Spot a Real Pollachi Coconut

Weight: It should feel heavy—signs of water-filled freshness.

Shell: Clean, green (tender) or brown (mature), with an even husk.

Sound: A nice slosh when shaken means it's fresh.

Source: Buy only from verified suppliers like Pollachi Farmers Market to ensure quality.

Our Promise: Quality You Can Trust

We follow strict standards—from semi-husking and sorting to hygienic packing—so every coconut retains its freshness during export. We deliver to homes, stores, and restaurants across the USA, UK, and the Middle East.

From Pollachi, With Love

Pollachi isn’t just a place—it’s a feeling. A feeling of community, love, and gratitude for the land. And our coconuts carry that emotion. They’re not just tasty—they’re filled with the warmth of the people who grow them.

Conclusion

So why is Pollachi coconut the tastiest? Because it’s more than just a fruit—it’s a reflection of nature’s perfection, human dedication, and timeless tradition. When you taste one, you’re not just enjoying a snack—you’re tasting a story, a legacy, a little piece of home from Tamil Nadu. Order now at Pollachi Farmers Market and experience the flavor the world is falling in love with

0 notes

Text

Vinyl Chloride Monomer (VCM) Price Index: Market Analysis, Trend, News, Graph and Demand

Vinyl Chloride Monomer (VCM) is a vital petrochemical product primarily used in the production of polyvinyl chloride (PVC), a versatile plastic material found in construction, automotive, packaging, and medical applications. The VCM market has experienced substantial price fluctuations in recent years, driven by a combination of feedstock availability, global demand for PVC, supply chain disruptions, environmental regulations, and geopolitical factors. The price dynamics of VCM are intricately tied to the cost of ethylene, a key raw material derived from crude oil and natural gas, making it sensitive to changes in energy markets. As global crude oil prices rise or fall, so too do the production costs for ethylene and, consequently, vinyl chloride monomer. This close relationship underscores the importance of monitoring upstream energy markets to anticipate changes in VCM pricing trends.

In addition to raw material costs, demand from downstream PVC manufacturers plays a crucial role in shaping the VCM price landscape. The construction industry, which is one of the largest consumers of PVC, has a significant impact on VCM consumption. In regions where infrastructure development is growing rapidly, such as Asia-Pacific, particularly China and India, demand for VCM remains strong, placing upward pressure on prices. On the other hand, during periods of economic downturn or slow construction activity, VCM demand tends to weaken, leading to softer prices. Seasonal demand variations also contribute to short-term volatility in the market, especially in countries where construction activities are highly seasonal due to weather conditions.

Get Real time Prices for Vinyl Chloride Monomer (VCM): https://www.chemanalyst.com/Pricing-data/vinyl-chloride-monomer-69

Supply-side factors also have a profound effect on VCM prices. Plant turnarounds, unexpected shutdowns, and natural disasters affecting petrochemical facilities can significantly constrain supply, causing prices to spike. For instance, hurricanes along the Gulf Coast of the United States, a major petrochemical hub, have previously disrupted VCM production and distribution, leading to tight supply and elevated prices in the North American market. In contrast, the addition of new production capacities, particularly in Asia, has helped stabilize supply in recent years, although this often leads to competitive pricing pressures, especially when supply outpaces demand growth.

Geopolitical tensions and trade policies are additional factors that influence the vinyl chloride monomer market. Trade restrictions, tariffs, and sanctions on petrochemical products can alter the flow of goods across regions, impacting pricing strategies and availability. For example, changes in U.S.-China trade relations have periodically disrupted the flow of raw materials and finished products, leading to price uncertainty. In some cases, producers have sought alternative markets or adjusted their pricing strategies to remain competitive, further contributing to price volatility.

Environmental regulations are increasingly shaping the VCM market as well. The production of vinyl chloride monomer involves hazardous chemicals and produces emissions that are subject to strict oversight in many countries. Compliance with environmental standards often necessitates investment in cleaner technologies and production processes, which can increase production costs and, in turn, influence pricing. Furthermore, growing awareness and demand for sustainable materials have led to scrutiny of PVC and its raw materials, prompting some companies to explore bio-based or alternative feedstocks. These developments could eventually reshape the VCM market landscape and impact price structures over the long term.

The global pandemic in 2020 had a notable impact on the vinyl chloride monomer market. Lockdowns, travel restrictions, and reduced industrial activity led to a significant drop in demand for PVC products, which in turn reduced VCM consumption and prices. However, the recovery period saw a surge in construction activity, particularly as governments invested in infrastructure projects to stimulate economic growth. This rebound led to a sharp increase in PVC demand, thereby lifting VCM prices. As markets continue to stabilize post-pandemic, VCM prices have started to normalize, though uncertainties remain due to inflationary pressures, interest rate fluctuations, and changing consumer behavior.

Technological advancements and process innovations also play a role in the pricing of vinyl chloride monomer. More efficient production methods can lower costs, enabling producers to offer more competitive prices. Additionally, the integration of digital technologies and data analytics in the chemical manufacturing sector has improved forecasting and supply chain management, allowing companies to respond more swiftly to market changes. These efficiencies may help mitigate extreme price swings and enhance overall market stability in the long run.

Regional dynamics are another important aspect of the VCM market. Asia-Pacific remains the largest and fastest-growing region, with high consumption driven by rapid industrialization and urban development. China, in particular, is both a major producer and consumer of VCM, and any shift in its domestic policies or economic performance has ripple effects on global pricing. North America and Europe, while mature markets, continue to play significant roles in terms of technological development and regulatory influence. In emerging markets across Africa and Latin America, rising construction activities and increasing demand for durable plastic products are expected to drive future growth in VCM consumption.

Looking ahead, the vinyl chloride monomer market is expected to remain dynamic, with prices influenced by a complex interplay of economic, environmental, and geopolitical factors. While short-term fluctuations will likely continue due to supply disruptions or raw material volatility, long-term growth in infrastructure, housing, and industrial applications will sustain demand for VCM. As producers adapt to changing regulatory environments and technological innovations, the market will continue to evolve, offering both challenges and opportunities for stakeholders across the supply chain. Strategic planning, investment in sustainable practices, and close monitoring of global trends will be essential for companies seeking to navigate the evolving VCM price landscape effectively.

Get Real time Prices for Vinyl Chloride Monomer (VCM): https://www.chemanalyst.com/Pricing-data/vinyl-chloride-monomer-69

Contact Us:

ChemAnalyst

GmbH - S-01, 2.floor, Subbelrather Straße,

15a Cologne, 50823, Germany

Call: +49-221-6505-8833

Email: [email protected]

Website: https://www.chemanalyst.com

#Vinyl Chloride Monomer Price#Vinyl Chloride Monomer Prices#India#United kingdom#United states#Germany#Business#Research#Chemicals#Technology#Market Research#Canada#Japan#China

0 notes

Text

Fire and Safety Courses in Kerala: Building a Safer Tomorrow

In today's fast-paced industrial world, safety is no longer a choice,it is a must. With industrialization taking an accelerated pace in India, Kerala, in particular, being no less appreciated with the growth, has thus created an unprecedented demand for safety professionals who are skilled enough to serve its industry. Fire and safety courses in Kerala are the buttresses attempting to support the greater need by offering rich training to equip people with opportunities for worthy careers that serve society.

Need for Fire and Safety Education

Fire and safety education prepare a person to avert, take control of, and react in situations like fires, chemical spills, and other hazards in the workplace. Whether a construction site, manufacturing unit, oil refinery, or residential complex, safety professionals would ensure compliance with safety protocols to prevent accidents and save lives.

An ideal fire and safety course will be structured to cover many topics of fire prevention techniques, risk assessments, occupational health and emergency response planning, and use of safety equipment. The aim is to impart not only theoretical knowledge but also practical skills that are narrowed down through hands-on training and real-life scenario simulations.

The Rising Need in Kerala

Kerala sees a higher demand for trained safety staff as its industrial centers and infrastructure projects grow. Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram, and Kozhikode host many sectors—construction, shipping, oil & gas, and manufacturing—that need strict safety rules.

This growth in the area has caused more schools to offer fire and safety classes in Kerala. These schools teach local students and also draw people from all over India and Gulf countries because they provide top-notch education and job chances.

What's in Fire and Safety Classes?

You can find fire and safety classes in Kerala at different levels—from quick certificates to full diplomas and degrees. Here's a look at what these classes cover:

1. Certificate Classes

These are short programs that last from a few weeks to a few months. They teach the basics in areas like simple fire safety first aid, and how to get out in an emergency.

2. Diploma Programs

Diploma courses often take 6 months to a year and cover topics such as:

Industrial safety

Building site safety

Fire avoidance and safeguarding methods

Safety for the surroundings

Health and cleanliness in the workplace

3. Advanced Diploma and Postgraduate Courses

An advanced program is specifically developed for specialists seeking to develop further in their fields or to specialize in:

Fire engineering

Process safety management

Safety auditing and risk assessment

4. Practical Training Modules

Practical training is emphasized by most reputable institutions through:

Fire drills

Rescue operations

Simulation-based learning

Use of firefighting equipment

Career Opportunities After Completing Fire and Safety Courses

Areas of employment for the graduates of fire and safety courses in Kerala include:

- Oil and gas industries

- Chemical plants

- Construction companies

- Manufacturing units

- Airports and seaports

- Government emergency services

- Hospitals and large commercial establishments

The graduates can work in the following positions:

- Fire Safety Officer

- HSE (Health, Safety & Environment) Manager

- Risk Assessor

- Safety Auditor

- Industrial Hygienist

- Safety Supervisor

There are many positions with attractive pay scales abroad, especially in the Middle East because of their strict enforcement of safety standards.

Why is Fire and Safety Education in Kerala?

Among several reasons, several make Kerala the preferred location for fire and safety training:

A High Literacy Rate: Since the population in Kerala is highly educated, it is more open to technical education.

Best Quality Institutions: Kerala consists of some of the best institutes in India with good training infrastructure and experienced faculty.

Affordable Courses: Fees in Kerala are comparatively lower than any other state.

Placement: Placement services are offered within campus by most institutes, and they have tie-ups with major industries in India and abroad.

Best Practice in Fire and Safety Training programs

To meet this increasing need for safety and fire experts, a number of state institutions in Kerala now have begun providing special courses. However, the quality and reputation of programs are very different. Ideally, choosing a suitable training institute is critical for creating a rocky foundation to pursue a successful life.

1. Accreditation and Affiliations

Verify whether the institute is accredited by reputable accrediting bodies providing qualifications which are endorsed by body. International accreditation does not just add to your resume but is usually a functional requirement by international companies during hire.

2. Curriculum Relevance

Choose courses which provide all-inclusive training in areas such as fire prevention, risk management, emergencies, industrial safety and environmental health. Successful courses combine theoretical knowledge with practical skills.

3. Infrastructure and Facilities

College with sophisticated training grounds in the form of safety laboratories and facilities for mock emergency drills enable students to learn skills that will be applicable in real life emergencies. Make sure that the educational facility has practical training, incorporates such drills as emergency drills and makes safety gear available to students in the course of their studies.

4. Experienced Faculty

Professors with professional experience bring real advice and industry examples to the discussion in the classroom. Their mentorship covers practical things, thus giving the students a deeper understanding of what employers seek and how work teams are.

5. Placement Support

High emphasis on placement services with appropriate industry connections is a major strength. Study their history with alumni and if you can, talk to them directly to get firsthand experience.

In Kerala a number of institutions of education correspond with these standards and equipped these institutions with able graduates to enter professional lives in India and abroad. Research thoroughly, tour the campus if possible, and ask the faculty or students already a part of the institution to help you do your enrollment.

As these businesses and sectors grow, there is an even greater need for concrete workplace safety practices. Importance of the fire and safety education received in Kerala comes in the form of equally nurturing professionals who are apt to ensure the lives and properties are protected. Using their elaborate curricula, train-on-job and acquisition of international certifications, organizations like Techshore inspection services are playing a significant role in the promotion of safety and security in the working place.

If you have any ambition to set up a career of meaning and international significance, enrolment in fire and safety programs available in Kerala may enable to succeed on the personal level and on the global level in your field.

Conclusion

As businesses keep on growing and developing, the significance of workplace safety becomes even more essential. Kerala's fire and safety courses are taking center stage in creating professional experts who can protect lives and assets. With extensive curricula, hands-on training, and international certifications, organizations such as Techshore Inspection Services are setting the pace towards creating a safer and more secure world.If you’re considering a career that offers both personal satisfaction and global opportunities, enrolling in fire and safety courses in Kerala could be your first step toward a meaningful and impactful profession.

#fire and safety course in kochi#fire and safety management course#fire and safety courses in kerala

0 notes