#GranularSoundProcessing

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A Short History of Granular Synthesis – Part 4

This is the last article concerning the history of working with sonic grains. But the matter itself – doing granular synthesis, granular tweaking of sound, granular processing in general – this matter will be dealt with in the next series called “In the World of Grains”). And if you´d like to dive deep into working with sonic grains at once, well, take a look here: https://www.dev.rofilm-media.net/node/332

For those of my readers, who like to dive deeper into the science of working with grains of sound I strongly recommend the book “Microsound” written by Curtis Roads (MIT Press, 2004).

The example of Prof. Paul Lansky is kind of atypical for the matter of this book. After pioneering on the field of computer based sound generating and sound processing, and after working on this field for about 44 years, he turned his back on all kinds of electronic music and went (back) to composing acoustical instrumental music.

But what he left back had strong influence on a whole generation of electronic and/or computer based musicians, composers and producers. He developed not only software for generating and processing sound and for composing, but invented even the computer languages, which made it easier to write those software.

Thanks to Paul Lansky the processing of life sound became a manageable matter at all (more about this aspect in the next series about granular sound processing called “In the World of Grains”).

Lansky worked with so called “real-world” sounds a lot, and here his emphasis lay on processing the sound of the human voice. In his works “Idle Chatter” (1985), “just_more_idle_chatter” (1987), and “Notjustmoreidlechatter” (1988) he used a special kind of granular technique, which is now called “micromontage”. The generated and used grains are uncommonly large (80 ms and more). Their contend is pitched to common scales, and their arrangement builds clear rhythmical structures. (the video is available only in the e-book)

Prof. Barry Truax focusses on real-time granular synthesis. In fact he was the first to work with this technique, the first, who even made it technically possible. “Real-time granular synthesis” means a (mostly presampled, but sometimes even played life) stream of sound is processed, chopped into grains, which are manipulated (pitch, length, structure) and arranged in time (density, rhythm) in real time, opposed to the non-real-time techniques of before, where grains were generated from diverse sonic material, stored somehow (on tape in the beginnings of granular synthesis, later on computer storage media), and then manipulated and arranged, more or less piece by piece, grain by grain.

(the video is available only in the e-book)

All of the popular granular applications (VSTs, AUs etc.) of today work with real-time granular synthesis, some more, some less consequently (see the upcoming series of articles called “In the World of Grains” here at my site, or read about my book here: https://www.dev.rofilm-media.net/node/332).

Truax was also the first, who worked with samples as raw material for granular sound processing in his compositions.

And he was the first to explore the sonic potential of the field of – or should I say the area of conflict -synchronous and asynchronous granular synthesis, where the grains are arranged equally along the time axis, generating the notion of frequency and pitch, and enabling pitch shifting and time stretching effects (synchronous order), or appear in a random, irregular order with unequal spaces between the grains (asynchronous order).

(the video is available only in the e-book)

His composition “Riverrun” from 1986 is an impressive demonstration of using this field of sonic conflict in a creative way (see below).

Truax developed a detailed system of how to compose using granular sound processing, a system, that may be called even a set of comprehensive rules. He himself used to call it a compositional “strategy”.

As this chapter is meant to give just a brief overview, only one last matter shall be mentioned here, before I spend some words on the composition “Riverrun”. In his essay “Ecologically-based granular synthesis” (together with Damián Keller, 1998) Truax and Keller explored the matter of classifying environmental-based sounds and using them in compositions utilizing granular synthesis, thus taking a huge step forward in structuring the idea (perhaps even the ideology) of what I like to call “The World is Sound”, and making it manageable in real compositions.

But now for “Riverrun”. Let me quote the composer himself:

“Riverrund is based on synthesized grains … . However … the resulting textures are always dynamically changing and range from swarms of relatively isolated sound events to fused sound masses of great internal complexity, much like environmental sound generally and water sound in particular. The fundamental paradox of granular synthesis – that the enotmously rich and powerful textures it produces result from being based on the most “trivial” grains of sound – suggested a metaphoric relation to the river whose power is based on the accumulation of countless “powerless” droplets of water.” (in “Composing with Real-Time Granular Sound”, JSTOR “Perspectives of New Music Vol. 28 n.2, 1990)

I apologise to all of the younger musicians, composers and scientists, who are working with granular synthesis, exploring the field of granular sound processing, and finding their own ways and systems to develop the utilizing of sonic grains in art until today, for not mentioning them here. As I mentioned above: this chapter is meant to deliver only a brief historical overview.

Even if dealt with in more detail in the chapter about software later in this book, the DAW based software application “Reaktor” (first publicly available version in the late 1990s) by Native Instruments deserves to be mentioned here in the history department of this book, as it is the first DAW based and popular piece of software, which is able to do granular processing of sound.

or you might like to visit our Facebook group https://www.facebook.com/groups/rofilmmedia

… to be continued.

#grains#granular#granularsynthesis#granularsoundprocessing#sonicgrains#noise#experimental#electronicmusic#experimentalmusic#lansky#paullansky#microsound#idlechatter#micromontage#fx#granularfx#riverrun

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

All e-books contain hundreds of example videos. This offer ends 15 January 2023 and won´t be prolonged. Read all the details here: https://dev.rofilm-media.net

Enjoy your day!

Rolf

#generative#generativemusic#modularsynths#musicproduction#sounddesign#sequencer#sequencers#makinggenerativemusic#modulargenerative#generativemodular#learninggenerative#learningmodular#grains#granular#granularsynthesis#granularsoundprocessing#sonicgrains#noise#experimental#electronicmusic#experimentalmusic

0 notes

Text

My Musical Dialogues With Chat GPT – Part 3 “Granular Sound”

Enjoy your day!

Rolf

#GranularSoundProcessing#AudioSampling#SoundSynthesis#MusicProduction#DigitalAudioWorkstations#DAW#GranularSynthesizerSoftware#ChatGPT#SoundDesign#ExperimentalMusic#TimeStretching#PitchShifting#AudioArt#Soundscapes#SoundManipulation#SoundEffects#fx#soundfx#AudioMicroscopy#SoundEditing#AcousticProcessing#SignalProcessing#SoundGeneration#AudioTechnology#MusicTheory#SoundEngineering#SoundArchitecture#AudioVisualization#AudioAnalysis#SoundLibraries

0 notes

Text

The first part of “A Journey Into MGranular MB” is online now:

youtube

I´m showing and explaining the general structure of the application as well as the relationship between frequency bands and voices and the way they cooperate.

#granular#grains#granularFX#sonicgrains#granularsoundprocessing#grainsound#sound#sounddesign#sounddesigner#melda#meldaproduction#soundFX#soundeffects#multiband#frequencybands#music#musicproduction#musicproducer#vst#granularvst#grainfx#graineffects#effectplugin#plugin#musicplugin#MgranularMB#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

A Short History of Granular Synthesis – Part 1

When we look at the way how granular sound processors, namely granular synthesis VSTs and other granular sound processing software, are used, we might think this technique is practised either by quite old so called “serious” electronic musicians, or by quite young artists and producers, who are interested in spectacular effects generated with free granular synths, or with expensive graintable synthesizers, doing granular sampling, or using hardware granular synths. Either way it looks like being a quite young approach to working with sound. Being asked my oldest grandson told me that it was – maybe – 10 years ago, when musicians started to process sound on a granular basis, whereas one of my sons-in-law thought to know it better, when he claimed, that it was in the 1940s, when someone – he didn´t know the name – started using granular techniques with sound.

Both were terribly wrong – and so was I before I started preparing for this book. (see also “In the World of Grains” here: https://www.dev.rofilm-media.net/node/332 )

The idea of understanding sound as a more or less organised aggregation of short grains was firstly uttered by the Dutch philosopher and scientist Isaac Beeckman in the first decade of the 17th century, more than 400 years ago!

But without the technical requirements and conditions to make musical use of the idea, all thoughts and thinking about a possibly granular structure of sound vanished into oblivion for more than 330 years.

It wasn´t a musician nor a philosopher who revived the notion of sound as a cluster of grains – probably without knowing about Beeckman at all.

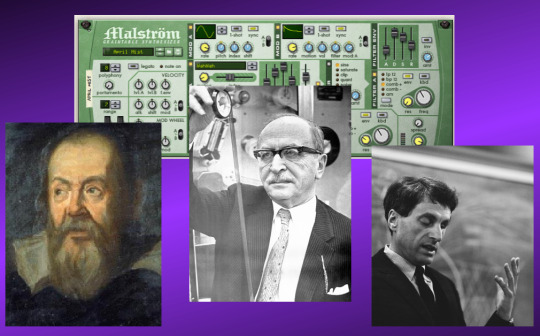

During the first half of the 20th century the development of the quantum theory gained speed. Leading physicists like Max Planck, Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg and others smashed the notion of things like time and space as a continuum, and proved, that time, space and even reality as a whole has a corned, a grained, a granular structure, with these “corns”, these “grains” called “quanta”. Quantum physics was the new rock´n´roll of the scientists.

And therefore it might not be that astonishing, that – in 1946 - it was the physicist and mathematician Dennis Gabor, who came up with what would lead to the modern granular processing of sound of today.

He even constructed a number of electro-mechanical machines producing “quanta of sound”, as he called them. These machines were huge “monsters” reminding of cinematographs.

But his most important contribution to the further development of working with grains of sound was his research concerning the influence of the length of a grain and the frequency of its content on how the human ear conceives them. These researches laid the ground for bringing the matter from the realm of physics to the area of art and music.

Still – it would last 13 more years (1959/1960) before grains appeared in a piece of musical art, and it was the Greek composer Iannis Xenakis, who let the world hear the first composition, which was – partly – based on granular techniques: Analogique A-B.

Without going into too many details here in this short brief, there shall be mentioned the following at least: Xenakis recorded a string orchestra, cut the tape into certain tiny parts, rearranged them, glued the snippets together again, added the sound from electronic tone generators to the rearranged snippets, and re-rcorded the whole thing. Then he let the orchetra play a small part of the previously recorded piece. Then the orchestra stops playing and gets a musical answer from the tape. The answers from the – let me call it – composed grains get more and more perfect. It seems, that the tape sound undergoes a kind of learning process. Then both, the acoustical instruments as well as the tape, the grains and the electronically produced sounds play together.

Imagine, what an immense amount of working hours and how detailed a compositional plan it will have needed to work with tape snippets of grain lengths in such a manner!

Later – in 1971 – Xenakis published “Formalized Music”, a book in which he layed out a musical theory of how to compose using grains of sound.

But in the meantime – between 1960 and 1971 – some other interesting things happened. Things, which would accelerate the development of granular sound machines and software.

… to be continued.

or you might like to visit our Facebook group https://www.facebook.com/groups/rofilmmedia

#grains#granular#granularsynthesis#granularsoundprocessing#sonicgrains#noise#experimental#electronicmusic#experimentalmusic#Xenakis#Beeckman#IsaacBeeckman

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Short History of Granular Synthesis – Part 3

Alright then. Let´s do the next steps in the history of grains of sound, granular synthesis music, granular resynthesis etc.

(excerpt from my ebook “In the World Of Grains” https://www.dev.rofilm-media.net/node/332 all embedded videos are available only in the book)

The contribution to (and importance for) the further development of granular sound processing techniques and granular sound processing behaviour until today is more in developing new perspectives on musical art and on artwork with sound in general, than in refining technical or compositional tools concerning the granular level of audible goings on.

Let me name only two of the above mentioned assumptions.

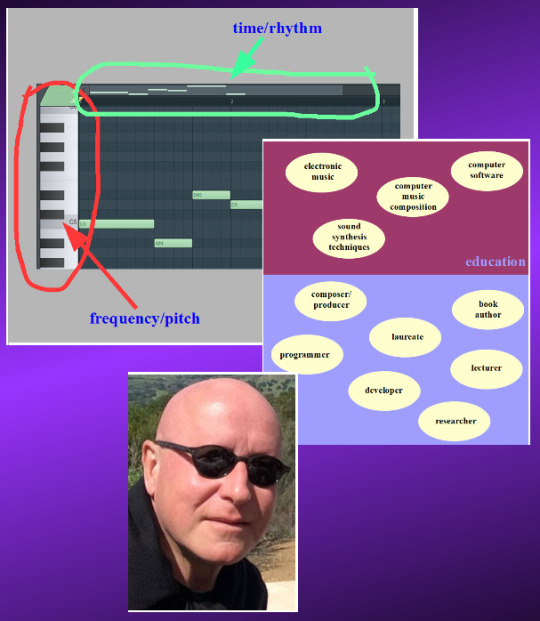

Before sonic grains entered the playground frequency and time were dealt with as different things in music. In simple words the relation “frequency is pitch, and time is rhythm” had been generally accepted for centuries. Granular sound processing smashed this assumption to pieces.

The second – and perhaps even more radical change of view – concerns the relation of a composition to the sounds it uses (or is meant for).

The composers set up their parts, write their music, a music, which is written in certain forms (and even freedom of design is “form”), which then are performed using – sound. The composition and the sound belong to each other, but they are different things, different aspects of the whole piece of audible art.

Granular synthesis and granular sound processing smashed even this assumption. Using granular techniques – and before using the techniques thinking in dimensions of sonic grains – made it possible to compose sound in an even more detailed – and free – way, than it had been possible to do with pitch, key, rhythm etc. in so called classical compositions.

Composing sound instead of composing pitch and rhythm, developing sound scales instead of pitch scales etc. got into reach. And even the idea of sound, which composes itself has changed from a mere philosophical idea to a real field of research – through granular sound processing.

It´s not the goal of this brief historical overview to name all important composers, scientists, musicians and great thinkers, who contributed – and partly still do so - to the matter of grains of sound. And even if it hurts – more than a bit – not to talk about such phantastic people like e.g. Ingrid Chantal Daubechies, Walter Branchi, Simon Emmerson etc., let me say some words about only three of them at the end of this short chapter: Barry Truax, Curtis Roads and Paul Lansky.

Curtis Roads, even if contributing a lot not only to – let me call it – granular music itself, but also to the development of computer software to deal with the granular aspects of sound, he never limited himself to using only granular sound generating, granular sound processing and granular approaches to composing. His goal was rather creating and investigating music, which uses - what he called - “polychromatic timbres”. Granular techniques were just one of a bunch of ways to generate these timbres.

His education as well as his professional works are as “polychromatic” as his compositions.

It may come in handy to give a simplified explanation of the term “polychromatic timbres” at this point. The classical limitation of dividing an octave into 12 notes of a certain pitch, each of which laying apart from its neighbours by 1 semi-tone, which all classical scales can chose their notes from(e.g. C major: C-D-E-F-G-A-B), is overcome by microtonal scales, in which the differences in pitch can be less than 1 semitone. There are a whole bunch of ways (or systems) to divide octaves and other intervals, and build microtonal scales.

A (or even the?) framework of exploring these different – desirably all possible – ways of dividing is called a “polychromatic system” (of pitch).

Polychromatic timbres expand this idea from pitch to spectra and their changes in time ( = sound).

Roads uses (pre-)sampled material, taking a non-real-time approach to granular synthesis/sound design.

In his piece “nscor”, first published at the International Computer Music Conference in New York, 1980 he demonstrated what the term “polychromatic timbre” means in a real composition. Containing prerecorded sounds generated by utilizing different techniques like subtractive synthesis, additive synthesis, frequency modulation and granular synthesis, granular techniques cover only about 50 seconds (in parts of 3.5 seconds, 12 seconds and 34 seconds at 3 different moments in the piece) of the whole work, which is (in the version of 1986) 8 minutes and 58 seconds long.

In a short email conversation concerning the permission of using a part of his works in the video, which accompanies this book, Prof. Roads remarked, that his piece “Prototype” from 1975 was a better example than nscor, and sent me the most important parts – concerning the matter of early applications of granular synthesis – as a sound file, which is now part of the video (see link). I´d like to thank Prof Roads for the hint and the sound material here in this book.(the video is available only ion my e-book)

Nevertheless Roads performs all different ways to use granular sound design, which were technically possible in the 1980s. We find accumulations of layered grains, which explosively accured building bell-like sounds, that seem to be generated by frequency modulation, but trying to rebuild these sounds using only FM methods you discover, that what you are trying is a mission impossible.

There is a longer lasting granular part working with different densities, starting with a dense cloud-like bunch of grains, whose individual sounds are unidentifiable. Reducing the densitiy the individual grains, respectively their sounds, get more and more recognisable until they dissolve and go up in single sonic events like the flashes of a christmas sparkler.

Changing the spectral bandwidth of the grains´ content sets a whole world of sonic experience, which could well be called “polychromatic” itself.(see also here: https://www.dev.rofilm-media.net/node/332)

... to be continued

#grains#granular#granularsynthesis#granularsoundprocessing#sonicgrains#noise#experimental#electronicmusic#experimentalmusic#Roads#CurtisRoads#polychromatic#nscor#prototype#truax#barrytruax#lansky#paullansky

0 notes

Text

A Short History of Granular Synthesis – Part 1

When we look at the way how granular sound processors, namely granular synthesis VSTs and other granular sound processing software, are used, we might think this technique is practised either by quite old so called “serious” electronic musicians, or by quite young artists and producers, who are interested in spectacular effects generated with free granular synths, or with expensive graintable synthesizers, doing granular sampling, or using hardware granular synths. Either way it looks like being a quite young approach to working with sound. Being asked my oldest grandson told me that it was – maybe – 10 years ago, when musicians started to process sound on a granular basis, whereas one of my sons-in-law thought to know it better, when he claimed, that it was in the 1940s, when someone – he didn´t know the name – started using granular techniques with sound.

Both were terribly wrong – and so was I before I started preparing for this book. (see also “In the World of Grains” here: https://www.dev.rofilm-media.net/node/332 )

The idea of understanding sound as a more or less organised aggregation of short grains was firstly uttered by the Dutch philosopher and scientist Isaac Beeckman in the first decade of the 17th century, more than 400 years ago!

But without the technical requirements and conditions to make musical use of the idea, all thoughts and thinking about a possibly granular structure of sound vanished into oblivion for more than 330 years.

It wasn´t a musician nor a philosopher who revived the notion of sound as a cluster of grains – probably without knowing about Beeckman at all.

During the first half of the 20th century the development of the quantum theory gained speed. Leading physicists like Max Planck, Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg and others smashed the notion of things like time and space as a continuum, and proved, that time, space and even reality as a whole has a corned, a grained, a granular structure, with these “corns”, these “grains” called “quanta”. Quantum physics was the new rock´n´roll of the scientists.

And therefore it might not be that astonishing, that – in 1946 - it was the physicist and mathematician Dennis Gabor, who came up with what would lead to the modern granular processing of sound of today.

He even constructed a number of electro-mechanical machines producing “quanta of sound”, as he called them. These machines were huge “monsters” reminding of cinematographs.

But his most important contribution to the further development of working with grains of sound was his research concerning the influence of the length of a grain and the frequency of its content on how the human ear conceives them. These researches laid the ground for bringing the matter from the realm of physics to the area of art and music.

Still – it would last 13 more years (1959/1960) before grains appeared in a piece of musical art, and it was the Greek composer Iannis Xenakis, who let the world hear the first composition, which was – partly – based on granular techniques: Analogique A-B.

Without going into too many details here in this short brief, there shall be mentioned the following at least: Xenakis recorded a string orchestra, cut the tape into certain tiny parts, rearranged them, glued the snippets together again, added the sound from electronic tone generators to the rearranged snippets, and re-rcorded the whole thing. Then he let the orchetra play a small part of the previously recorded piece. Then the orchestra stops playing and gets a musical answer from the tape. The answers from the – let me call it – composed grains get more and more perfect. It seems, that the tape sound undergoes a kind of learning process. Then both, the acoustical instruments as well as the tape, the grains and the electronically produced sounds play together.

Imagine, what an immense amount of working hours and how detailed a compositional plan it will have needed to work with tape snippets of grain lengths in such a manner!

Later – in 1971 – Xenakis published “Formalized Music”, a book in which he layed out a musical theory of how to compose using grains of sound.

But in the meantime – between 1960 and 1971 – some other interesting things happened. Things, which would accelerate the development of granular sound machines and software.

… to be continued.

read more about sonic grains here: "In the World of Grains": https://www.dev.rofilm-media.net/node/332

or you might like to visit our Facebook group https://www.facebook.com/groups/rofilmmedia

#grains#granular#granularsynthesis#granularsoundprocessing#sonicgrains#noise#experimental#electronicmusic#experimentalmusic#Xenakis#Beeckman#IsaacBeeckman

1 note

·

View note

Text

A Short History of Granular Synthesis – Part 1

When we look at the way how granular sound processors, namely granular synthesis VSTs and other granular sound processing software, are used, we might think this technique is practised either by quite old so called “serious” electronic musicians, or by quite young artists and producers, who are interested in spectacular effects generated with free granular synths, or with expensive graintable synthesizers, doing granular sampling, or using hardware granular synths.

Either way it looks like being a quite young approach to working with sound. Being asked my oldest grandson told me that it was – maybe – 10 years ago, when musicians started to process sound on a granular basis, whereas one of my sons-in-law thought to know it better, when he claimed, that it was in the 1940s, when someone – he didn´t know the name – started using granular techniques with sound.

Both were terribly wrong – and so was I before I started preparing for this book. (see also “In the World of Grains” here: https://www.dev.rofilm-media.net/node/332 )

The idea of understanding sound as a more or less organised aggregation of short grains was firstly uttered by the Dutch philosopher and scientist Isaac Beeckman in the first decade of the 17th century, more than 400 years ago!

But without the technical requirements and conditions to make musical use of the idea, all thoughts and thinking about a possibly granular structure of sound vanished into oblivion for more than 330 years.

It wasn´t a musician nor a philosopher who revived the notion of sound as a cluster of grains – probably without knowing about Beeckman at all.

During the first half of the 20th century the development of the quantum theory gained speed. Leading physicists like Max Planck, Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg and others smashed the notion of things like time and space as a continuum, and proved, that time, space and even reality as a whole has a corned, a grained, a granular structure, with these “corns”, these “grains” called “quanta”. Quantum physics was the new rock´n´roll of the scientists. https://youtu.be/77ZdNvWIH1k

And therefore it might not be that astonishing, that – in 1946 - it was the physicist and mathematician Dennis Gabor, who came up with what would lead to the modern granular processing of sound of today.

He even constructed a number of electro-mechanical machines producing “quanta of sound”, as he called them. These machines were huge “monsters” reminding of cinematographs.

But his most important contribution to the further development of working with grains of sound was his research concerning the influence of the length of a grain and the frequency of its content on how the human ear conceives them. These researches laid the ground for bringing the matter from the realm of physics to the area of art and music.https://youtu.be/qxC65dfWvEY

Still – it would last 13 more years (1959/1960) before grains appeared in a piece of musical art, and it was the Greek composer Iannis Xenakis, who let the world hear the first composition, which was – partly – based on granular techniques: Analogique A-B.

Without going into too many details here in this short brief, there shall be mentioned the following at least: Xenakis recorded a string orchestra, cut the tape into certain tiny parts, rearranged them, glued the snippets together again, added the sound from electronic tone generators to the rearranged snippets, and re-rcorded the whole thing.

Then he let the orchetra play a small part of the previously recorded piece. Then the orchestra stops playing and gets a musical answer from the tape. The answers from the – let me call it – composed grains get more and more perfect. It seems, that the tape sound undergoes a kind of learning process. Then both, the acoustical instruments as well as the tape, the grains and the electronically produced sounds play together.

Imagine, what an immense amount of working hours and how detailed a compositional plan it will have needed to work with tape snippets of grain lengths in such a manner!

Later – in 1971 – Xenakis published “Formalized Music”, a book in which he layed out a musical theory of how to compose using grains of sound.

But in the meantime – between 1960 and 1971 – some other interesting things happened. Things, which would accelerate the development of granular sound machines and software.

… to be continued.

or you might like to visit our Facebook group https://www.facebook.com/groups/rofilmmedia

#grains#granular#granularsynthesis#granularsoundprocessing#sonicgrains#noise#experimental#electronicmusic#experimentalmusic#Xenakis#Beeckman#IsaacBeeckman

0 notes