#Gitali Roy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

charulata, satyajit ray 1964

*

youtube

reality bites, ben stiller 1994

youtube

girl, interrupted, james mangold 1999

#charulata#the lonely wife#satyajit ray#1964#madhabi mukherjee#soumitra chatterjee#shailen mukherjee#shyamal ghoshal#gitali roy#bholanath koyal#suku mukherjee#dilip bose#nilotpal dey#bankim ghosh#reality bites#ben stiller#1994#winona ryder#ethan hawke#girl. interrupted#james mangold#1999#angelina jolie#der schritt vom wege#effi briest#throne of blood#se7en#taxi driver#whisky mit wodka#irgendwann im april

0 notes

Photo

Charulata (1964) dir. Satyajit Ray

#charulata#satyajit ray#indian cinema#bengali film#Madhabi Mukherjee#Gitali Roy#parallel cinema#60s movies

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Charulata, Satyajit Ray (1964)

#Satyajit Ray#Soumitra Chatterjee#Madhabi Mukherjee#Shailen Mukherjee#Shyamal Ghoshal#Gitali Roy#Subrata Mitra#Dulal Dutta#1964

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

চারুলতা, Satyajit Ray (1964)

Cinematography: Subrata Mitra | India

#Charulata#চারুলতা#Satyajit Ray#Gitali Roy#Madhabi Mukherjee#Soumitra Chatterjee#B & W#Fate#Looks#Beds#Doors#1964

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Charulata (1964, India)

The first non-European to win the Nobel Prize in Literature was Rabindranath Tagore, winning in 1913 as the fourteenth laureate. Tagore, a Bengali author, represented the West’s increasing awareness of one aspect of Indian culture, just as Western filmmakers and moviegoing audiences became more aware of one aspect of Indian culture through Satyajit Ray’s films. Ray and Tagore come together in Charulata, Ray’s cinematic adaptation of Tagore’s novella Nastanirh. Nine years after his self-taught directorial debut, Ray had quickly become one of the most prominent figures in international cinema, and he himself believed that Charulata represented his work, “with the fewest flaws”. Also known as The Lonely Wife in English, Bengali-language Charulata requires some knowledge of Indian history and society, specifically its colonial ties to Britain and especially gender-informed attitudes towards women. Though I agree with Ray’s assessment of Charulata’s polish – of the seven movies of his I have seen – I would not say this is his best movie. Considering the quality of his work, even his lowest-standard work is worth witnessing.

Our setting is Calcutta, sometime in the late nineteenth century. Charulata (Madhabi Mukherjee, whose character is referred to as “Charu”) lives with her husband Bhupati (Sailen Mukherjee; no relation to his co-star) in their two-storied, terraced home. She is a housewife who reads any literature and poetry she can find in her spare time; he is the editor of a political newspaper supporting Indian independence. Bhupati’s offices are in a different section of the house, where women are not expected to be, if not outright barred from. So Charu’s days, when she is not reading, are often tedious. Her room, the house’s high walls, and an expansive backyard are all that make up her world. Not that Bhupati is unaware of his wife’s loneliness; he employs his elder brother Umapada (Shyamal Ghoshal; barely in this film) so that Charu has company with his wife, Manda (Gitali Roy). But Manda is too frivolous for Charu. So when Bhupati’s cousin Amal (Soumitra Chatterjee) arrives, Bhupati encourages Amal – a writer – to cultivate Charu’s literary interests.

What follows is a connection between two creative souls as intense as could be imagined. Charu and Amal might not be culture-shaping, headline-writing creators (yet), but their passions are sincere, stemming from their life experiences in times of self-discovery. Passing interests become a lifestyle. Love intermingles with rivalry, competing love. Ray, who also wrote the adapted screenplay and composed the theme music, is able to contain complicated emotions into uncluttered stories. In Charulata, that means planning out a seven-and-a-half-minute opening scene where there is almost no dialogue to introduce the audience to Charu – her personality, her dreams, her isolation. A less confident and skilled director-writer might use narration or spend double or triple that time to depict a character’s interactions with others to grant the audience a portrait of what we need to know about a character.

Permit me a fantasy, but it is moments like these – and countless others during Ray’s Apu trilogy – that make me wonder if Satyajit Ray would have been a transformational force in silent film had he been born some decades earlier. For he is excellent in strategizing and writing out moments where nary a word is spoken, where ideas and feelings are conveyed through the simplest things such as where a character has positioned their body, who or what are they looking at, and what they might be doing when no one else is in the vicinity. In a film where the characters use words to express themselves naturally, Ray needs no words to do so. This diligence is something not often thought about when a Ray movie (or anyone else’s movie, for that matter) is playing. Yet that attention in Ray’s screenplay to granular details is what inspires Charulata’s pathos, as well as in the Apu trilogy and 1966′s Nayak.

Yet there are moments in Charulata that will escape Western viewers. Writing for British film magazine Sight & Sound in 1982, Ray noted that some of the authors mentioned and alluded to in the film as well as songs used will only be accessible to those knowledgeable about Bengali culture. Repeated references to nineteenth century Bengali author Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay appear in the opening minutes. In the aforementioned opening scene, Charu quietly sings Chattopadhyay’s name to herself. Minutes later, Amal arrives at his cousin’s house – his hair wet, his clothes dirty from the storm outside – and quotes from Chattopadhyay, underlining an intellectual and emotional connection to Charu that lovers of Bengali literature will recognize instantly. And if you were wondering if I knew about all of this beforehand and am the most adventurous person when it comes to non-English language literature, the answer is no: I looked it up. This review and this blog is written for an English-speaking audience, and the expectation is that English speakers will take the most out of these movie write-ups. This point on Bengali literary references is just one illustration of how Charulata – which is comprehensible for Western viewers without knowledge of Bengali literature – is operating in meticulous ways that are known and unknown to us viewers.

Here is another point unknown to most in the West: Ray’s adaptation of Charulata concentrates on Charu, shifting the Tagore novella’s focus away from Bhupati. Literary critics of the Tagore novella have noted how its narrative concentration on Bhupati showcases how oblivious he is to his wife’s dissatisfaction with her life. Ray, by entitling his film Charulata and by giving Madhabi Mukherjee far more screentime than Sailen Mukherjee, attempts a feminist approach that mostly works. The complete lack of women engaged in political debates in the household and the newspaper’s headquarters displays, without pontification, how women were discouraged from engaging in, let alone speaking about, the nation’s politics and relationship to the British. Though Charulata seems to be supportive of her husband’s pro-independence positions, the film suggests how Indian women, in this case Bengali women, are more connected to certain populations and policies than Bengali men. The absence of feminist voices creates an echo chamber of self-confirmation – creating an environment similar to the undeserved air of confidence Amal exudes when contemplating his relationship to his wife. A similar dynamic can be applied to Amal’s beliefs – though not as damagingly masculine as his cousin’s – about the role of women in Bengali literature.

The budding relationship of Charu and Amal first exists in a place familiar, confining: a private sphere where women are restricted in action and thought. Charu attempts to reclaim this space as hers, asking Amal to never reveal the poetry he writes in her company to others. These verses are written in a personal notebook Charu gives to Amal. That sort of request goes beyond forbidden friendships and love affairs. Those words, composed in a particular place, supported by the care of a particular person, might have been written by Amal, but Charu feels some sense of ownership, too. This is a new experience for Charu, to see someone engaged in a creative process, let alone designating her as his muse (”muse” is used here not necessarily to connote romantic objectification as occasionally implied, and will be best understood when one views the film). So when Amal violates that trust, Charulata begins to resolve as a narrative, to the only conclusion that might be bearable for the three central protagonists.

Without the performances from the Soumitra Chatterjee and Madhabi Mukherjee, Charulata would not be as impactful as it is. Mukherjee, with her wondrous expressions and facial acting, is incredible as the titular character. In the film’s quietest, stillest moments, she is occupying her character’s life – her pangs of joyfulness and frustration etched on her forehead, eyes, and so many frowns – and showing the audience all that needs to be known as early as possible. It is a stunning performance. Second to Mukherjee is Chatterjee, balancing playfulness and an unwieldy amount of the film’s most visible empathy for Charu. Soulmates though Chatterjee and Madhabi Mukherjee might play, their characters have varying levels of comfort in how they approach sharing their interests with others. There is the necessary narrative friction here, and their performances make the finale all the more crushing for everyone involved – yes, even for Shailen Mukherjee’s negligent Bhupati.

Cinematographer Subrata Mitra – a Ray regular – and his tracking shots float across the house, only venturing outside for the film’s ten-minute scene in the backyard garden, with Soumitra Chatterjee swinging herself back and forth. It is evocative camerawork, unafraid of almost invasive close-ups meant to mark a character’s discomfort with the current situation. The final shot of Charulata is the stuff of vehement mixed opinions (I believe the effect to be unnecessary). Art director/production designer Bansi Chandragupta consulted with Ray well before shooting began to examine Ray’s blueprints of the household – carefully sketched like an architect’s work, along with furniture that Ray thought appropriate for the household. Chandragupta’s and Ray’s sets are a mix of traditional Indian and European designs, reflective of the worlds Bhupati is torn by and the upper-class privilege he thinks little of.

Satyajit Ray is not a director known for unambiguous conclusions, unscathed consciences. Charulata represents one of the most jagged conclusions he has directed and written, designed to linger long after the credits have finished. For Bhupati and Charu, their nest of comfort and homeliness is broken. For Amal (and perhaps Charu, too), what was once a haven has become a reminder. Heartbreak needs no translation.

My rating: 8/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found here.

#Charulata#Satyajit Ray#Rabindranath Tagore#Soumitra Chatterjee#Madhabi Mukherjee#Shailen Mukherjee#Shyamal Ghoshal#Gitali Roy#Subrata Mitra#Bansi Chandragupta#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

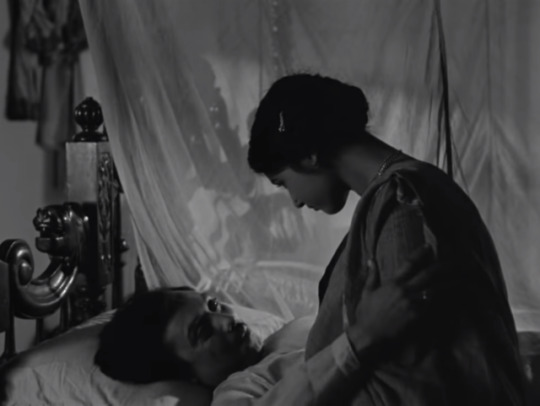

Madhabi Mukherjee and Soumitra Chatterjee in Charulata (Satyajit Ray, 1964) Cast: Madhabi Mukherjee, Soumitra Chatterjee, Shailen Mukherjee, Shyamal Ghoshal, Gitali Roy. Screenplay: Satyajit Ray, based on a story by Rabindranath Tagore. Cinematography: Subrata Mitra. Production design: Bansi Chandragupta. Music: Satyajit Ray. Charulata (Madhabi Mukherjee) is the beautiful, bored wife of the wealthy Bhupati (Shailen Mukherjee), who spends his time working on his newspaper devoted to the independence of India. At the start of the film, behind the opening credits, we watch as she embroiders a handkerchief for him, then Ray's ever-fluid camera follows her as she wanders through the richly appointed rooms of their house, gazing at the outside world through opera glasses and searching for something to read. At one point, Bhupati enters the house, smoking his pipe and reading a book, and walks right by her, not seeing or acknowledging her. But he becomes conscious of his wife's ennui and invites her brother, Umapada (Shyamal Ghoshal), and his wife, Manda (Gitali Roy), to live with them, and turns over the management of his business affairs to Umapada so Bhupati can devote more time to his newspaper. But Manda is empty-headed and prefers playing card games to providing intellectual companionship. Then Bhupati's cousin Amal (Soumitra Chatterjee), an aspiring writer, comes to visit, and Charulata is immediately attracted to him because of his literary interests and his sensitive poetic nature. In a scene set in the neglected garden of Bhupati's house, Amal writes poetry while Charulata soars on a swing, the camera tracking her movements. Their conversation inspires Charulata to express herself in writing, and she succeeds in getting a piece published about her memories of the village where she grew up -- even inspiring a little envy on Amal's part. Then we learn that Umapada has embezzled money from Bhupati and he and Manda have disappeared. Despondent, Bhupati tells Amal that he has lost trust in everyone but him, which stirs Amal's guilt: He realizes that he and Charulata have fallen in love, and rather than add to the burden of betrayal that has already been unloaded on Bhupati, he leaves suddenly. Charulata's grief at Amal's departure opens Bhupati's eyes to what has happened between his wife and his cousin. At the film's end, Charulata and Bhupati reach out for each other, but Ray chooses to depart from his usual mobile camera and to record the moment in a series of still photographs, over which he superimposes not the title of the film but that of the story by Rabindranath Tagore on which it was based: "The Broken Nest."

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Holy Man | Satyajit Ray | 1965

Gitali Roy, Satindra Bhattacharya

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mahapurush মহাপুরুষ, The Holy Man (1965)

Buchki: Call that a letter? Seven lines in all - two of Shelley, two of Chandidas, two lines of Tagore! And the rest- How are you? I'm fine!

#lmao feel u girl#mahapurush#the holy man#satyajit ray#Gitali Roy#Satindra Bhattacharya#i mean this isn't his best film but enjoyable tbh#bengali cinema#drafts and stuff

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Charulata (1964) dir. Satyajit Ray

#charulata#satyajit ray#indian cinema#bengali film#Shyamal Ghoshal#Gitali Roy#60s movies#parallel cinema

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Charulata (1964) dir. Satyajit Ray

#charulata#satyajit ray#indian cinema#bengali film#Madhabi Mukherjee#Gitali Roy#Soumitra Chatterjee#60s movies#parallel cinema

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

চারুলতা, Satyajit Ray (1964)

Cinematography: Subrata Mitra | India

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Holy Man | Satyajit Ray | 1965

Prasad Mukherjee, Santosh Dutta, Renuka Roy, Gitali Roy, Satindra Bhattacharya

#Prasad Mukherjee#Santosh Dutta#Renuka Roy#Gitali Roy#Satindra Bhattacharya#Satyajit Ray#The Holy Man#1965

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Holy Man | Satyajit Ray | 1965

Gitali Roy

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Charulata (AKA The Lonely Wife) | Satyajit Ray | 1964

Gitali Roy, Madhabi Mukherjee

19 notes

·

View notes