#Bansi Chandragupta

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Apu Trilogy

Subir Banerjee in Pather Panchali (Satyajit Ray, 1955)

Cast: Kanu Bannerjee, Karuna Bannerjee, Chunibala Devi, Uma Das Gupta, Subir Banerjee, Runki Banerjee, Reba Devi, Aparna Devi, Tulsi Chakraborty. Screenplay: Satyajit Ray, based on a novel by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay. Cinematography: Subrata Mitra. Production design: Bansi Chandragupta. Film editing: Dulal Dutta. Music: Ravi Shankar.

When I first saw Pather Panchali I was in my early 20s and unprepared for anything so foreign to my experience either in life or in movies. And as is usual at that age, my response was to mock. So half a century passed, and when I saw it again both the world and I had changed. I now regard it as a transformative experience -- even for one whom the years have transformed. What it shows us is both alien and familiar, and I wonder how I could have missed its resonance with my own childhood: the significance of family, the problems consequent on adherence to a social code, the universal effect of wonder and fear of the unknown, the necessity of art, and so on. Central to it all is Ray's vision of the subject matter and the essential participation of Ravi Shankar's music and Subrata Mitra's cinematography. And of course the extraordinary performances: Kanu Bannerjee as the feckless, deluded father, clinging to a role no longer relevant in his world; Karuna Bannerjee as the long-suffering mother; Uma Das Gupta as Durga, the fated, slightly rebellious daughter; the fascinating Chunibala Devi as the aged "Auntie"; and 8-year-old Subir Banerjee as the wide-eyed Apu. It's still not an immediately accessible film, even for sophisticated Western viewers, but it will always be an essential one, not only as a landmark in the history of movie-making but also as an eye-opening human document of the sort that these fractious times need more than ever.

Smaran Ghosal in Aparajito (Satyajit Ray, 1956)

Cast: Pinaki Sengupta, Smaran Ghosal, Kanu Bannerjee, Karuna Bannerjee, Ramani Sengupta, Charuprakash Ghosh, Subodh Ganguli. Screenplay: Satayajit Ray, Kanaili Basu, based on a novel by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay. Cinematography: Subrata Mitra. Production design: Bansi Chandragupta. Film editing: Dulal Dutta. Music: Ravi Shankar

As the middle film of a trilogy, Aparajito could have been merely transitional -- think for example of the middle film in The Lord of the Rings trilogy: The Two Towers (Peter Jackson, 2002), which lacks both the tension of a story forming and the release of one ending. But Ray's film stands by itself, as one of the great films about adolescence, that coming-together of a personality. The "Apu trilogy," like its source, the novels by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, is a Bildungsroman, a novel of ... well, the German Bildung can be translated as "education" or "development" or even "personal growth." In Aparajito, the boy Apu (Pinaki Sengupta) sprouts into the adolescent Apu (Smaran Ghosal), as his family moves from their Bengal village to the city of Benares (Varanasi), where Apu's father continues to work as a priest, while his mother supplements their income as a maid and cook in their apartment house. When his father dies, Apu and his mother move to the village Mansapota, where she works for her uncle and Apu begins to train to follow his father's profession of priest. But the ever-restless Apu persuades his mother to let him attend the village school, where he excels, eventually winning a scholarship to study in Calcutta. In Pather Panchali (1955), the distant train was a symbol for Apu and his sister, Durga, of a world outside; now Apu takes a train into that world, not without the painful but necessary break with his mother. Karuna Bannerjee's portrayal of the mother's heartbreak as she releases her son into the world is unforgettable. Whereas Pather Panchali clung to a limited setting, the decaying home and village of Apu's childhood, the richness of Aparajito lies in its use of various settings: the steep stairs that Apu's father descends and ascends to practice his priestly duties on the Benares riverfront, the isolated village of Mansapota, and the crowded streets of Kolkata, all of them magnificently captured by Subrata Mitra's cinematogaphy.

Soumitra Chatterjee in The World of Apu (Satyajit Ray, 1959)

Cast: Soumitra Chatterjee, Sharmila Tagore, Swapan Mukherjee, Alok Chakravarty, Dhiresh Majumdar, Dhiren Ghosh. Screenplay: Satyajit Ray, based on a novel by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay. Cinematography: Subrata Mitra. Production design: Bansi Chandragupta. Film editing: Dulal Dutta. Music: Ravi Shankar.

The exquisite conclusion to Ray's trilogy takes Apu (Soumitra Chatterjee) into manhood. He leaves school, unable to afford to continue into university, and begins to support himself by tutoring while trying to write a novel. When his friend Pulu (Swapan Mukherjee) persuades him to go along to the wedding of his cousin, Aparna (Sharmila Tagore), Apu finds himself marrying her: The intended bridegroom turns out to be insane, and when her father and the other villagers insist that the astrological signs indicate that Aparna must marry someone, Apu, the only available male, is persuaded, even though he regards the whole situation as nonsensical superstition, to take on the role of bridegroom. (It's a tribute to both the director and the actors that this plot turn makes complete sense in the context of the film.) After a wonderfully awkward scene in which Apu and Aparna meet for the first time, and another in which Aparna, who has been raised in comparative luxury, comes to terms with the reality of Apu's one-room apartment, the two fall deeply in love. But having returned to her family home for a visit, Aparna dies in childbirth. Apu refuses to see his son, Kajal (Alok Chakravarty), blaming him for Aparna's death and leaving him in the care of the boy's grandfather. He spends the next five years wandering, working for a while in a coal mine, until Pulu finds him and persuades him to see the child. As with Pather Panchali and Aparajito, The World of Apu (aka Apur Sansar) stands alone, its story complete in itself. But it also works beautifully as part of a trilogy. Apu's story often echoes that of his own father, whose desire to become a writer sometimes set him at odds with his family. When, in Pather Panchali, Apu's father returns from a long absence to find his daughter dead and his ancestral home in ruins, he burns the manuscripts of the plays he had tried to write. Apu, during his wanderings after Aparna's death, flings the manuscript of the novel he had been writing to the winds. And just as the railroad train figures as a symbol of the wider world in Pather Panchali, and as the means to escape into it in Aparajito, it plays a role in The World of Apu. Instead of being a remote entity, it's present in Apu's own back yard: His Calcutta apartment looks out onto the railyards of the city. Adjusting to life with Apu, Aparna at one point has to cover her ears at the whistle of a train. Apu's last sight of her is as she boards a train to visit her family. And when he reunites with his son, he tries to play with the boy and a model train engine. The glory of this film is that it has a "happy ending" that is, unlike most of them, completely earned and doesn't fall into false sentiment. I don't use the world "masterpiece" lightly, but The World of Apu, both alone and with its companion films, seems to me to merit it.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

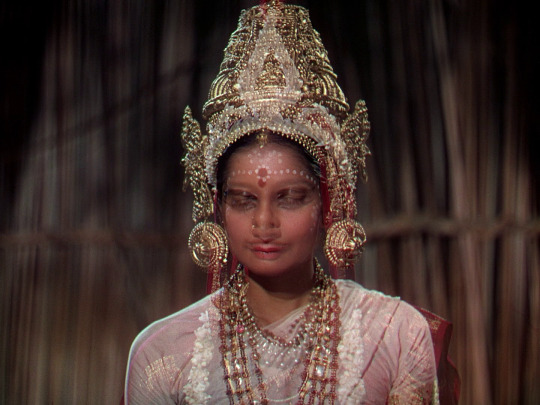

The River (Jean Renoir, 1951).

#the river#the river (1951)#jean renoir#suprova mukerjee#patricia walters#adrienne corri#radha#claude renoir#george gale#eugène lourié#bansi chandragupta

105 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Charulata (1964, India)

The first non-European to win the Nobel Prize in Literature was Rabindranath Tagore, winning in 1913 as the fourteenth laureate. Tagore, a Bengali author, represented the West’s increasing awareness of one aspect of Indian culture, just as Western filmmakers and moviegoing audiences became more aware of one aspect of Indian culture through Satyajit Ray’s films. Ray and Tagore come together in Charulata, Ray’s cinematic adaptation of Tagore’s novella Nastanirh. Nine years after his self-taught directorial debut, Ray had quickly become one of the most prominent figures in international cinema, and he himself believed that Charulata represented his work, “with the fewest flaws”. Also known as The Lonely Wife in English, Bengali-language Charulata requires some knowledge of Indian history and society, specifically its colonial ties to Britain and especially gender-informed attitudes towards women. Though I agree with Ray’s assessment of Charulata’s polish – of the seven movies of his I have seen – I would not say this is his best movie. Considering the quality of his work, even his lowest-standard work is worth witnessing.

Our setting is Calcutta, sometime in the late nineteenth century. Charulata (Madhabi Mukherjee, whose character is referred to as “Charu”) lives with her husband Bhupati (Sailen Mukherjee; no relation to his co-star) in their two-storied, terraced home. She is a housewife who reads any literature and poetry she can find in her spare time; he is the editor of a political newspaper supporting Indian independence. Bhupati’s offices are in a different section of the house, where women are not expected to be, if not outright barred from. So Charu’s days, when she is not reading, are often tedious. Her room, the house’s high walls, and an expansive backyard are all that make up her world. Not that Bhupati is unaware of his wife’s loneliness; he employs his elder brother Umapada (Shyamal Ghoshal; barely in this film) so that Charu has company with his wife, Manda (Gitali Roy). But Manda is too frivolous for Charu. So when Bhupati’s cousin Amal (Soumitra Chatterjee) arrives, Bhupati encourages Amal – a writer – to cultivate Charu’s literary interests.

What follows is a connection between two creative souls as intense as could be imagined. Charu and Amal might not be culture-shaping, headline-writing creators (yet), but their passions are sincere, stemming from their life experiences in times of self-discovery. Passing interests become a lifestyle. Love intermingles with rivalry, competing love. Ray, who also wrote the adapted screenplay and composed the theme music, is able to contain complicated emotions into uncluttered stories. In Charulata, that means planning out a seven-and-a-half-minute opening scene where there is almost no dialogue to introduce the audience to Charu – her personality, her dreams, her isolation. A less confident and skilled director-writer might use narration or spend double or triple that time to depict a character’s interactions with others to grant the audience a portrait of what we need to know about a character.

Permit me a fantasy, but it is moments like these – and countless others during Ray’s Apu trilogy – that make me wonder if Satyajit Ray would have been a transformational force in silent film had he been born some decades earlier. For he is excellent in strategizing and writing out moments where nary a word is spoken, where ideas and feelings are conveyed through the simplest things such as where a character has positioned their body, who or what are they looking at, and what they might be doing when no one else is in the vicinity. In a film where the characters use words to express themselves naturally, Ray needs no words to do so. This diligence is something not often thought about when a Ray movie (or anyone else’s movie, for that matter) is playing. Yet that attention in Ray’s screenplay to granular details is what inspires Charulata’s pathos, as well as in the Apu trilogy and 1966′s Nayak.

Yet there are moments in Charulata that will escape Western viewers. Writing for British film magazine Sight & Sound in 1982, Ray noted that some of the authors mentioned and alluded to in the film as well as songs used will only be accessible to those knowledgeable about Bengali culture. Repeated references to nineteenth century Bengali author Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay appear in the opening minutes. In the aforementioned opening scene, Charu quietly sings Chattopadhyay’s name to herself. Minutes later, Amal arrives at his cousin’s house – his hair wet, his clothes dirty from the storm outside – and quotes from Chattopadhyay, underlining an intellectual and emotional connection to Charu that lovers of Bengali literature will recognize instantly. And if you were wondering if I knew about all of this beforehand and am the most adventurous person when it comes to non-English language literature, the answer is no: I looked it up. This review and this blog is written for an English-speaking audience, and the expectation is that English speakers will take the most out of these movie write-ups. This point on Bengali literary references is just one illustration of how Charulata – which is comprehensible for Western viewers without knowledge of Bengali literature – is operating in meticulous ways that are known and unknown to us viewers.

Here is another point unknown to most in the West: Ray’s adaptation of Charulata concentrates on Charu, shifting the Tagore novella’s focus away from Bhupati. Literary critics of the Tagore novella have noted how its narrative concentration on Bhupati showcases how oblivious he is to his wife’s dissatisfaction with her life. Ray, by entitling his film Charulata and by giving Madhabi Mukherjee far more screentime than Sailen Mukherjee, attempts a feminist approach that mostly works. The complete lack of women engaged in political debates in the household and the newspaper’s headquarters displays, without pontification, how women were discouraged from engaging in, let alone speaking about, the nation’s politics and relationship to the British. Though Charulata seems to be supportive of her husband’s pro-independence positions, the film suggests how Indian women, in this case Bengali women, are more connected to certain populations and policies than Bengali men. The absence of feminist voices creates an echo chamber of self-confirmation – creating an environment similar to the undeserved air of confidence Amal exudes when contemplating his relationship to his wife. A similar dynamic can be applied to Amal’s beliefs – though not as damagingly masculine as his cousin’s – about the role of women in Bengali literature.

The budding relationship of Charu and Amal first exists in a place familiar, confining: a private sphere where women are restricted in action and thought. Charu attempts to reclaim this space as hers, asking Amal to never reveal the poetry he writes in her company to others. These verses are written in a personal notebook Charu gives to Amal. That sort of request goes beyond forbidden friendships and love affairs. Those words, composed in a particular place, supported by the care of a particular person, might have been written by Amal, but Charu feels some sense of ownership, too. This is a new experience for Charu, to see someone engaged in a creative process, let alone designating her as his muse (”muse” is used here not necessarily to connote romantic objectification as occasionally implied, and will be best understood when one views the film). So when Amal violates that trust, Charulata begins to resolve as a narrative, to the only conclusion that might be bearable for the three central protagonists.

Without the performances from the Soumitra Chatterjee and Madhabi Mukherjee, Charulata would not be as impactful as it is. Mukherjee, with her wondrous expressions and facial acting, is incredible as the titular character. In the film’s quietest, stillest moments, she is occupying her character’s life – her pangs of joyfulness and frustration etched on her forehead, eyes, and so many frowns – and showing the audience all that needs to be known as early as possible. It is a stunning performance. Second to Mukherjee is Chatterjee, balancing playfulness and an unwieldy amount of the film’s most visible empathy for Charu. Soulmates though Chatterjee and Madhabi Mukherjee might play, their characters have varying levels of comfort in how they approach sharing their interests with others. There is the necessary narrative friction here, and their performances make the finale all the more crushing for everyone involved – yes, even for Shailen Mukherjee’s negligent Bhupati.

Cinematographer Subrata Mitra – a Ray regular – and his tracking shots float across the house, only venturing outside for the film’s ten-minute scene in the backyard garden, with Soumitra Chatterjee swinging herself back and forth. It is evocative camerawork, unafraid of almost invasive close-ups meant to mark a character’s discomfort with the current situation. The final shot of Charulata is the stuff of vehement mixed opinions (I believe the effect to be unnecessary). Art director/production designer Bansi Chandragupta consulted with Ray well before shooting began to examine Ray’s blueprints of the household – carefully sketched like an architect’s work, along with furniture that Ray thought appropriate for the household. Chandragupta’s and Ray’s sets are a mix of traditional Indian and European designs, reflective of the worlds Bhupati is torn by and the upper-class privilege he thinks little of.

Satyajit Ray is not a director known for unambiguous conclusions, unscathed consciences. Charulata represents one of the most jagged conclusions he has directed and written, designed to linger long after the credits have finished. For Bhupati and Charu, their nest of comfort and homeliness is broken. For Amal (and perhaps Charu, too), what was once a haven has become a reminder. Heartbreak needs no translation.

My rating: 8/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found here.

#Charulata#Satyajit Ray#Rabindranath Tagore#Soumitra Chatterjee#Madhabi Mukherjee#Shailen Mukherjee#Shyamal Ghoshal#Gitali Roy#Subrata Mitra#Bansi Chandragupta#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seven Minutes to Ecstacy

Seven Minutes to Ecstacy

In the whole of seven minutes, there are a few seconds of human speech.Rest is all about sights and sounds of Nature.Almost like a whodunit that boringly lulls you into an unsuspecting daydream only to be awakened by the shrill cries of a murder is this debut speciale!That maybe,the construct of a linear,simple thriller.Cut to the laziness swirling around of yet, another hot day, in a rural…

View On WordPress

#Apu#Bansi Chandragupta#Bengali#Cannes Film Festival#Cinematography#Durga#movies#Music#Pather Panchali#Ravi Shanker#Sarbojya#Satyajit Ray#Subroto Mitra

0 notes

Photo

Based on Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay‘s 1929 novel, the film took more than 2 years to shoot, due to Ray’s inability to raise funds (the Museum of Modern Art provided some funds, due to the encouragement of John Huston). He worked with an inexperienced cast and crew (including 21-year-old cameraman Subrata Mitra, and 28-year-old art director Bansi Chandragupta). Ray had met Chandragupta while working on Jean Renoir’s The River (1951). It was Renoir who encouraged Ray to pursue his dream of filming Pather Panchali.

Pather Panchali is regarded as one of the greatest films of all-time (appearing on Sight & Sound’s list since 1962, ranked as high as #6), but was almost lost due to a 1993 fire at the Motion Picture Academy storage facility in London, which severely damaged the negative master prints of all of Ray’s films. In 2013, the Criterion Collection, working with L’Immagine Ritrovata, an Italian restoration lab, restored the film (and the other 2 films in the Apu Trilogy), which was shown in May 2015 at MoMA, almost 60 years to the day it was first screened.

“Don’t be anxious. Whatever God ordains is for the best.”

Pather Panchali (Satyajit Ray, 1955)

568 notes

·

View notes

Photo

We are watching Shyam Benegal’s KALYUG on Wednesday, 6th December at 6pm.

“With Indian audiences geared towards kitsch and klutzy hi-jinks as entertainment, one can only hope that Kalyug will augur the commercial popularity of high quality films. Is it too much to ask for a little patience and a drop of depth from the audience?” - Madhu Trehan, India Today, May 1981

Produced by: Shashi Kapoor, Screenplay by: Girish Karnad & Shyam Benegal, Cinematography by: Govind Nihalani, Music by: Vanraj Bhatia, Dialogues by: Pt. Satyadev Dubey, Film Editing by: Bhanudas Divakar, Art Direction by: Bansi Chandragupta, & Costume Design by: Jennifer Kendal

0 notes

Photo

Satyajit Ray’s drawings of General Outram’s room (played by Richard Attenborough) in The Chess Players (Satyajit Ray, 1977) | Art direction by Bansi Chandragupta

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Madhabi Mukherjee and Soumitra Chatterjee in Charulata (Satyajit Ray, 1964) Cast: Madhabi Mukherjee, Soumitra Chatterjee, Shailen Mukherjee, Shyamal Ghoshal, Gitali Roy. Screenplay: Satyajit Ray, based on a story by Rabindranath Tagore. Cinematography: Subrata Mitra. Production design: Bansi Chandragupta. Music: Satyajit Ray. Charulata (Madhabi Mukherjee) is the beautiful, bored wife of the wealthy Bhupati (Shailen Mukherjee), who spends his time working on his newspaper devoted to the independence of India. At the start of the film, behind the opening credits, we watch as she embroiders a handkerchief for him, then Ray's ever-fluid camera follows her as she wanders through the richly appointed rooms of their house, gazing at the outside world through opera glasses and searching for something to read. At one point, Bhupati enters the house, smoking his pipe and reading a book, and walks right by her, not seeing or acknowledging her. But he becomes conscious of his wife's ennui and invites her brother, Umapada (Shyamal Ghoshal), and his wife, Manda (Gitali Roy), to live with them, and turns over the management of his business affairs to Umapada so Bhupati can devote more time to his newspaper. But Manda is empty-headed and prefers playing card games to providing intellectual companionship. Then Bhupati's cousin Amal (Soumitra Chatterjee), an aspiring writer, comes to visit, and Charulata is immediately attracted to him because of his literary interests and his sensitive poetic nature. In a scene set in the neglected garden of Bhupati's house, Amal writes poetry while Charulata soars on a swing, the camera tracking her movements. Their conversation inspires Charulata to express herself in writing, and she succeeds in getting a piece published about her memories of the village where she grew up -- even inspiring a little envy on Amal's part. Then we learn that Umapada has embezzled money from Bhupati and he and Manda have disappeared. Despondent, Bhupati tells Amal that he has lost trust in everyone but him, which stirs Amal's guilt: He realizes that he and Charulata have fallen in love, and rather than add to the burden of betrayal that has already been unloaded on Bhupati, he leaves suddenly. Charulata's grief at Amal's departure opens Bhupati's eyes to what has happened between his wife and his cousin. At the film's end, Charulata and Bhupati reach out for each other, but Ray chooses to depart from his usual mobile camera and to record the moment in a series of still photographs, over which he superimposes not the title of the film but that of the story by Rabindranath Tagore on which it was based: "The Broken Nest."

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Anil Chatterjee and Madhabi Mukherjee in The Big City (Satyajit Ray, 1963) Cast: Madhabi Mukherjee, Anil Chatterjee, Haradhan Bannerjee, Vicky Redwood, Haren Chatterjee, Sefalika Devi, Jaya Bhaduri, Prasenjit Sarkar. Screenplay: Satyajit Ray, based on stories by Narendranath Mitra. Cinematography: Subrata Mitra. Art direction: Bansi Chandragupta. Film editing: Dulal Dutta. Music: Satyajit Ray. For a long time, cities got a bad rap in the movies: Think of Fritz Lang's soul-devouring futuristic city in Metropolis (1027), the hedonistic town that sends out tendrils like the sinister Woman From the City to ensnare country folk like The Man and The Wife in F.W. Murnau's Sunrise (1927), or the weblike New York City that blights the lives of John and Mary in The Crowd (King Vidor, 1928). But these are surviving remnants of the Romanticism that proclaimed "God made the country and man made the town." By the mid-20th century, even our poets, or at least our songwriters, had turned the great big city into a wondrous toy, just made for a girl and boy, and a place where if you can make it there, you can make it anywhere -- a heroic challenge. In The Big City, Satyajit Ray's Kolkata retains some of the old sinister qualities, but it also represents opportunity, especially for women emerging from the shadows of male domination. Ray's domestic drama doesn't set up a contrast between town and country so much as a contrast between the dark, cramped home that Subrata (Anil Chatterjee) and Arati Mazumdar (Madhabi Mukherjee) share with his mother and father and sister and their young son, and the expanse of the city, which offers up tempting alternatives to the tight nuclear household. And those alternatives are something that the older members of that household view with disgust and horror: Arati's going out to work and to supplement the small income of the traditional breadwinner, Subrata. A world opens up for Arati, though it's also a world that can easily crumble around her. Madhabi Mukherjee's wonderful performance as Arati, tremulous and naive at first but gradually gaining fire and courage, animates the film. Obstacles present themselves: Subrata loses his job as a bank clerk, and Arati eventually loses hers by standing up for the Anglo-Indian Edith (Vicky Redwood). But at the end, husband and wife, who have found their marriage tested by her employment, summon up reserves of courage to face the job market. The ending has been criticized as sentimental, but Ray has so carefully shown the growth of both Arati and Subrata that I find it hopeful.

0 notes

Photo

Aparajito (Satyajit Ray, 1956).

#satyajit ray#aparajito#subrata mitra#dulal dutta#bansi chandragupta#bibhutibhushan bandyopadhyay#kanailal basu#aparajito (1956)#movie stills#movie frames#diego salgado#sesión de madrugada#sesiondemadrugada#aparajito (el invencible)#aparajito (el invencible) (1956)

37 notes

·

View notes