#Gertrud de Lalsky

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

“Women Make Film” marathon reviews (1/6)

Mädchen in Uniform (1931, Germany)

By 1931, Germany stood at the brinks of history. Its harsh treatment by World War I’s victors and economic depression compelled some German politicians to channel wells of hatred for political expedience. In two years’ time, Weimar Germany would be transformed by the Nazi Party. Between 1918 and 1932, Germany’s cinema had flourished. The lack of money flowing into its industry inspired the creation of an array of genres and bold filmmaking styles, filmmakers working in innovative ways to express complicated ideas. German Expressionism – pairing wildly distorted geometric environs with plotlines on dark topics – is the most famous style of this era, even if it was not the most popular among German audiences during this time. Inspired by New Objectivity (films that focused on post-WWI middle class despair), though not an example of this movement, Leontine Sagan’s Mädchen in Uniform is one of the final great films of this period and a landmark piece of queer cinema. Mädchen in Uniform unleashed a final, rebellious roar against the authoritarian ideas that would overtake Germany.

Fourteen-year-old Manuela von Meinhardis (Hertha Thiele) is the new student at an all-girls boarding school helmed by Fräulein von Nordeck zur Nidden (Emilia Unda). Her father is a military officer who is barely home; her mother passed away when she was much younger. The staff seize Manuela’s belongings and outfits her in a vertical-striped uniform. Is this a school, a military barracks, or prison? In this sprawling complex with well-manicured grounds and Greco-Roman-inspired columns, its students march in rows of two, their transgressions receiving demerits from the staff. Beneath the regimentation, Manuela finds a welcoming, supportive culture among her fellow girls. Each teacher is responsible for their respective dormitory wing, and Manuela is assigned to Fräulein von Bernburg (Dorothea Wieck). Some of Manuela’s first greeters openly express their crush on the young von Bernburg – who kisses her students on the forehead good night.

At the end of her first day, Manuela is understandably still feeling nervous about whether she will adjust to life at this school. But lo and behold, Manuela, rather than a “good night” kiss on the forehead, receives a kiss on the lips from Fräulein von Bernburg. Manuela’s crush spirals into love for her schoolteacher, leading to an accidental climax that upends the school’s veneer of discipline and emotional/sexual repression.

In this boarding school, the students are starving for affection. The teachers address students by their surnames; they drill them in prim and proper womanhood daily. Letters to and from the outside world are verboten, nor are pictures of men. And in such a world, there is obviously no room for queerness, let alone any teenage romantic longing. But among the students, there is a crackling energy that abides despite the heavy-handed administration. That same energy sees numerous girls admit their attraction to others of the same gender to their classmates – even being selectively out to a trusted few is courageous, regardless of the era. Sagan and screenwriters Christa Winsloe (adapting her own stage play) and Friedrich Dammann (1951’s Happy Go Lovely) make no secrets that the film sympathizes with Manuela and her schoolmates. Emotional and sexual repression in the boarding school – and, by extension, the Germany of the near future – uphold the patriarchal norms and power structures espoused by the headmistress. Though the girls may not pull demeaning pranks or verbally abuse the headmistress and her deputies behind their backs (the stuff of rapidly dating 1980s American high school-set films), they actively undermine her stifling authority where possible – a veiled remark, disobedience.

Emilia Unda is fantastic in her role as the headmistress, a Prussian acting in a stereotypically militaristic manner. Hers is the performance of the film. But the headmistress cannot shape these young women alone, and that is where Dorothea Wieck’s Fräulein von Bernburg comes in. Von Bernburg has several interactions with Manuela – alone, among students and faculty – where it is clear she treads carefully between acting upon her feelings and exemplifying the professional values a teacher must maintain. During her classes with Von Bernburg, Manuela is unable to concentrate on her studies. In a post-class meeting, Manuela tearfully admits the following:

MANUELA: When you say goodnight and leave, and shut the door to your room, I stare at the door in darkness. I want to get up and come to you, but I know that I can’t. And I think of when I get older and have to leave the school and every night you will kiss other girls – FRÄULEIN VON BERNBURG: – What thoughts you have. MANUELA: – I love you so much… (...) FRÄULEIN VON BERNBURG: … Well, child, control yourself… You know I can’t make exceptions or the other girls will be jealous. I think of you often, Manuela.

Fräulein von Bernburg clearly has affection for her shy student – in facial expressions, in physical interactions, and off-screen actions (classmate Ilse, played by Ellen Schwanneke, tells Manuela after the latter was the star of the school play: “[Fräulein von Bernburg] didn’t say a word. But she watched you. You can’t imagine how closely she watched you.” Never does von Bernburg say she does not share, to some extent, Manuela’s feelings. Those who might deny those romantic undercurrents are ignoring that, as the film progresses, Mädchen in Uniform is absent any heterosexual baiting (if it wasn’t obvious by now, there is not a single male character in the film; this is eight years before George Cukor’s The Women) or implication among either character. Von Bernburg, acting on the behest of the headmistress, is as much an enforcer for the repressive school administration as she is a victim. To make things even more visually ambiguous, Thiele and Wieck are the same age – the film does an adequate job to make Thiele seem somewhat younger than Wieck, but it is obvious the actresses playing the schoolgirls are much too old for boarding school. Von Bernburg is aware of her status as a romantic interest of multiple students. This knowledge manifests itself in behavior alternatively disciplinarian and flirtatious (after comforting Ilse in one scene, Von Bernburg pats her bottom softly) – a challenge to the ethics of traditional student-teacher relationships.

Mädchen in Uniform does not have the production qualities of other German films of its era. Some of the editing can be rough; it is too easy to distinguish between the talents of the professional and non-professional actors (most of the students are played by non-professionals). However, cinematographers Reimar Kuntze (1938’s Carmen, la de Triana) and Franz Weihmayr (1936’s Ferryman Maria) use facial close-ups that are startling because of the film’s overwhelming proportion of medium shots. These sparingly-utilized close-ups contain the film’s emotional outbursts – whether for the purposes of liberation or repression – and intensify the effect. And though it may not be a German Expressionist film, Mädchen in Uniform also makes do with creative lighting. Paired with the black-and-white film, soft lighting is often present when Fräulein von Bernburg is in the frame – especially when she is with Manuela. Those scenes are laden with romantic tension, of actions and words withheld. Horizontal and vertical lighting and production design (from Fritz Maurischat and Friedrich Winckler-Tannenberg) emphasize the confining nature of this boarding school. In the film’s closing minutes, a camera pointed sharply downward into a stairwell breaks the viewer’s visual expectations in a scene of emotional chaos.

In the United States, the Motion Picture Production Code (also known as the Hays Code, this was a set of self-censorship guidelines for the film distribution) would not be fully enforced until 1934. But even in this pre-Code era of lax enforcement, Mädchen in Uniform was too much for the film censors. This distribution limbo would be broken by no less than Eleanor Roosevelt. Roosevelt exerted her influence as First Lady to secure for Mädchen in Uniform a limited release in the U.S. Back in Europe, the Nazi Party banned Leontine Sagan’s film shortly after they took power, despite the film toning down some of the lesbian themes from the stage play. Numerous cast and crew were Jewish, did not flee Germany, and were killed in concentration camps. The original stage play’s author, Christa Winsloe, was a lesbian herself – fleeing Germany for France in the late 1930s. For director Leontine Sagan, she directed two more films in Men of Tomorrow (1932) and Showtime (1946) after moving to Britain. She would remain there through World War II, until moving to South Africa and cofounding the National Theatre in Johannesburg.

Sagan would not live to see Mädchen in Uniform take its place in film history. Its potential popularity among LGBTQ+ viewers would be blunted for decades, due to the lasting popularity of Josef von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel (1930) in the queer community. The film existed in heavily edited prints until the 1970s. Germans would not be able to see the film unedited until a 1977 television airing. The fact that Mädchen in Uniform is a queer film favorite should not inspire hesitation for viewers who may think that this film is not “for them”. At its most basic level, this is a (mostly) spirited movie about a young girl’s search for belonging and nurturing. It captures the confusion and uncertainty of being a teenager (one attracted to others of the same gender, at that) and the thrill of having people who support you because of who you are. How fortunate that, despite the efforts of those who wanted to prevent audiences from seeing it, Mädchen in Uniform is now regarded as the classic that it is.

My rating: 9/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. Half-points are always rounded down. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog (as of July 1, 2020, tumblr is not permitting certain posts with links to appear on tag pages, so I cannot provide the URL).

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

NOTE: This is the first of an unspecified amount of film reviews on this blog relating to films that I saw as part of Turner Classic Movies’ (TCM) Women Make Film marathon.

#Madchen in Uniform#Mädchen in Uniform#Leontine Sagan#Hertha Thiele#Dorothea Wieck#Emilia Unda#Hedwig Schlichter#Ellen Schwanneke#Erika Mann#Gertrud de Lalsky#Christa Winsloe#Friedrich Dammann#Reimer Kuntze#Franz Weihmayr#Women Make Film#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

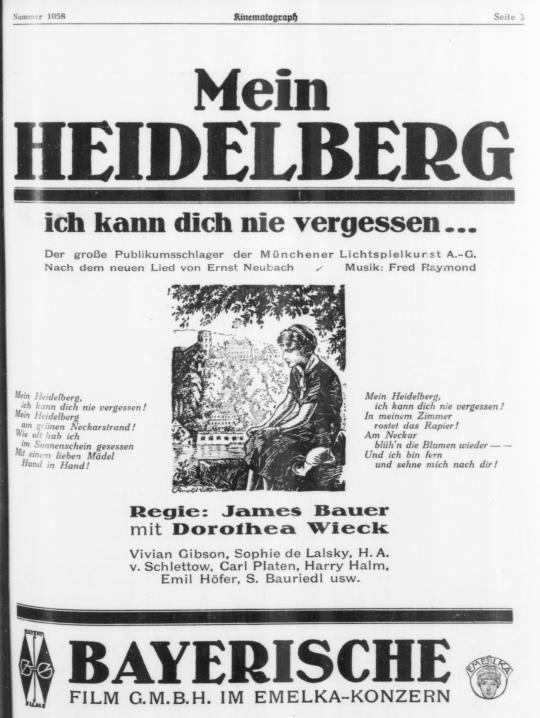

A poster of Emelka's film "Mein Heidelberg, ich kann Dich nicht vergessen" (1927) with Dorothea Wieck and others.

ERROR: no information if Sophie de Lalsky existed, but it's Gertrud de Lalsky who played here (better known as "somebody" in Mädchen in Uniform.)

#Dorothea Wieck#Emelka#1920's#1920s#retro#vintage#Mein Heidelberg ich kann Dich nicht vergessen#poster

0 notes

Text

Mädchen in Uniform

Year: 1931

Length: 1h 28min

Genre: Drama, Romance

Language: German

Director: Leontine Sagan

Starring: Hertha Thiele, Dorothea Wieck, Emilia Unda, Gertrud de Lalsky, Marte Hain, Hedwig Schlichter, Lene Berdolt

Story: Manuela von Meinhardis (Hertha Thiele) is enrolled in an all-girls school. There, she initially feels lost, due to her strict supervisors and teachers. Even though she quickly finds friends amongst her peers, she struggles with her school work. The only teacher who is nice to Manuela is Fräulein von Bernburg (Dorothea Wieck) and soon, Manuela falls in love with her.

Note: I watched this movie at university as part of a lecture series on films in pre-Nazi Germany, so I know more about it than the movies I usually review. I tried to keep the review as short as possible, but I might upload my lecture notes at a later point.

Pros:

Forbidden under Nazi regime: The movie was one of the first ones the Nazis banned when they gained power in 1933. The reason wasn’t the lesbian themes in the movie, but rather that many of the cast and crew were Jewish. Nevertheless, it is important to remember why Nazis banned certain movies and to look at this one, for example, with this knowledge in mind.

First lesbian movie: The film is one of the first ones with lesbian undertones ever made. I use the term undertones because, even though the lesbian themes in the movie were very obvious to me, they might be difficult to spot for a different audience, similar to the one which didn’t think Carol was a love story. To me, it’s obvious that Manuela is in love with Fräulein von Bernburg, and this isn’t a coincidence, but was deliberately chosen by Leontine Sagan, who was attracted to the play the film is based on due to its lesbian themes. Still, this isn’t an obvious love story like we are used to now in 2017, so don’t expect too much.

Happy ending: It is often said that Desert Hearts is the first lesbian movie with a happy ending. However, I would argue that it’s Mädchen in Uniform. Even though Manuela and Fräulein von Bernburg aren’t a couple in the end, they’re both alive and Fräulein von Bernburg even stands up for Manuela and defends her against the tyrannical headmistress (Emilia Unda)

Almost all-female cast and crew: If you remember Below Her Mouth, which came out a couple of months ago, you might also remember that it was praised for having an all-female crew. Mädchen in Uniform came out in 1931 – there isn’t a single man with a line of dialogue in this film. The screenplay was written by a woman, the director was a woman, some of the crew members were women. It’s sad that this is still something to be celebrated regarding a movie that came out in 2016.

No men: As I’ve already mentioned, there isn’t a single man in the movie. I can’t recall any other movie I’ve watched of which I can say that. All in all, it’s nice not having to watch men for a change.

Cons:

Student/teacher: Manuela is a 14-year-old girl who falls in love with her teacher. Nothing happens between them (apart from one kiss) and Fräulein von Bernburg is very strict when she tells Manuela that this won’t change. Still, such dynamics are always weird.

Child abuse: The boarding school Manuela goes to is horrible. The children are starved and when they write to their parents for help, their letters get intercepted and they are punished. The school uses Prussian discipline as a role model the students should follow as an example, but even though it is in accordance with the values of this time, the girls still suffer under the strict rules.

Homophobia: 4/10 – There is a discussion that love between two women isn’t normal. Manuela also gets into trouble for confessing her feelings for Fräulein von Bernburg.

Violence: 2/10 – Manuela’s love for Fräulein von Bernburg is never openly discussed, so the teachers tell the other students she is being punished for having been drunk. Manuela’s friends don’t understand why she is being locked away since all of them were drunk that night, but it never occurs to them that it could be because the teachers don’t think Manuela has an innocent “crush” on Fräulein von Bernburg, like most of the girls have.

Ending: The movie sort of has a happy ending, Manuela survives a mental breakdown and a suicide attempt and even though she and Fräulein von Bernburg don’t become a couple in the end (which would have been weird anyway), both of them are alive and overcome their obstacles.

Sexual orientation: The topic of sexual orientation isn’t discussed; it’s acceptable for the girls to sort of have a crush on Fräulein von Bernburg. She is the favourite teacher of everyone and the girls swoon over her in a way that suggests that at least some of them have a crush on her. They are all jealous of Manuela and one of her friends because Fräulein von Bernburg is the head of their dormitory and kisses them good night every evening. Rather than those feelings being accepted as romantic, it doesn’t occur to the students that they are in love with their teacher. When Manuela openly talks about her feelings and names them for what they are, she is immediately punished by the headmistress.

25 notes

·

View notes