#George Siegmann

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#The Birth of a Nation#Lillian Gish#Mae Marsh#Henry B. Walthall#Miriam Cooper#Ralph Lewis#George Siegmann#Walter Long#D. W. Griffith#1915

0 notes

Text

Der Mann, der lacht

Story: England im Jahr 1690: Gerade aus dem Exil heimgekehrt, um seinen kleinen Sohn Gwynplaine zu sehen, wird der Adlige Lord Clancharlie vom grausamen König James II. hingerichtet. Zuvor muss er jedoch erfahren, dass der König den Meisterchirurgen Dr. Hardquannone beauftragt hat, Gwynplaine grausam zu entstellen: Ein künstlich geschaffenes irres Grinsen verurteilt ihn dazu, von nun an auf ewig…

View On WordPress

#Carl Laemmle#Charles E. Whittaker#conrad veidt#Drama#Erno Rapee#George Siegmann#Gilbert Warrenton#Horror#J. Grubb Alexander#Josephine Crowell#Lew Pollack#Mary McLean#Mary Philbin#Old Hollywood#Olga Baclanova#Pauil Leni#Paul Kohner#the man who laughs#Tragik#Universal#Victor Hugo#Walter Anthony#Walter Hirsch#Wicked Cinema#Wicked Media#Wicked Vision Distribution

0 notes

Text

The Man Who Laughs finally premieres in Portugal. They do not care for spelling. I don't know who Groinploine is and I'm too afraid to ask.

Diário de Lisboa, 21 January 1930

"The man who laughs"

Victor Hugo's masterpiece was transplanted to the Cinema. A very bold enterprise that Paul [Leni], the great germanic director who passed away a few months ago, embarked on.

To make a film out of "The Man Who Laughs" meant that one had to reconstruct a whole time period, an absolutist and despotic 17th century England, when all the Lords were intangible, with the right of death over the commoner.

Above all, it meant not to destroy the work's spirit, by finding equivalences in pictures to Victor Hugo's flights of genius.

It meant that one had to find an actor with a prodigious mask, capable of fixing Gwynplaine's heinousness and his permanent smile, in his ripped mouth.

Finally, it would take millions to revive the opulence, the prosperity of James II and Queen Anne's Court.

Well, all this was done patiently, tiredlessly. And in the end, "Universal" has released a very precious production to the world, that costed two hundred thousand pound sterling and took two years to make.

"The Man Who Laughs", the film that Cinema Condes premiered in a soirée today, is not an ostentatious production like many others. It's a marvel of modern cinematography, not only for its respect to the fidelity of the reconstruction, but also for the tireless and magnificence of its sequences. It's a haunting film and, as a spectacle, it owes nothing to "The Hunchback of Notre Dame" and "The Phantom of the Opera".

The action is well paced, maintaining a growing interest and evoking and captivaring.

The acting is most noble: Conrad Veidt, the famous German actor, presents in a stupendous, unrivalled creation, as the monstrous Gwynplaine.

Mary Philbin as Dea, the fair blind girl.

Olga Baclanova as the voluptuous and depraved Duchess Josiana. Cesare Gravina, as the philosopher Ursus and George Siegmann as Doctor Hardquanonne, the Comprachico surgeon. Brandon Hurst as the jester Barkilphedro. Josephine Crowell as Queen Anne.

Sam DeGrasse as James II. There are more than twenty actors and three thousand extras in the film.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Birth of a Nation (D.W. Griffith, 1915)

Cast: Lillian Gish, Mae Marsh, Henry B. Walthall, Miriam Cooper, Mary Alden, Ralph Lewis, George Siegmann, Walter Long, Robert Harron, Wallace Reid, Joseph Henabery, Elmer Clifton, Josephine Crowell, Spottiswoode Aitken, George Beranger, Maxfield Stanley, Jennie Lee, Donald Crisp, Howard Gaye, Raoul Walsh. Screenplay: Thomas Dixon Jr., D.W. Griffith, Frank E. Woods, based on a novel and play by Dixon. Cinematography: G.W. Bitzer. Film editing: D.W. Griffith, Joseph Henabery, James Smith, Rose Smith, Raoul Walsh.

Is it an overstatement to say that the stench of The Birth of a Nation is more than a subset of the blight cast on American society and politics by slavery? Because Griffith's film informed an entire industry, not only with its undeniable influence on the language and grammar of film, but also in the tendency to valorize bigness above intimacy, action over thought, sensation over understanding that has characterized the mainstream of American movies. It was the first blockbuster. It was both intelligently crafted and abominably stupid. It just might be the most pernicious work of art ever made, a magnificent nauseating lie. Its portrait of Reconstruction warped the teaching of history for generations, and although the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan that it inspired has waned, we still find ourselves swatting down the heirs of the Klan like the Proud Boys, the Promise Keepers, and others who would defend what one of Griffith's title cards calls the "Aryan birthright." Even the reaction against The Birth of a Nation has its dark side: The recognition of the power of movies that followed its release eventually produced calls for censorship that would hamstring the medium. On the right, a suspicion that movies had the power to promote a leftist agenda led to the blacklist era, in which communists, not racists, were the target. And what is the crusade by some against "wokeness" in the media but another call for the kind of ideological purity that would stifle art? So to call The Birth of a Nation an essential film is an understatement. Looking at it as a demonstration of the ability of cinema to profoundly affect society could reveal it to be the most important movie ever made.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Movie Review: The Man Who Laughs (1928)

Title: The Man Who Laughs Release Date: November 4, 1928 Director: Paul Leni Production Company: Universal Pictures Main Cast: Mary Philbin as Dea Conrad Veidt as Gwynplaine Brandon Hurst as Barkilphedro Cesare Gravina as Ursus Olga Baclanova as Duchess Josiana Stuart Holmes as Lord Dirry-Moir Josephine Crowell as Queen Anne George Siegmann as Dr. Hardquanonne Sam De Grasse as King James…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Les Trois Mousquetaires.

1921.

Réalisation : Fred Niblo.

Scénaristes : Douglas Fairbanks, Edward Knoblock et Lotta Woods

Casting :

Douglas Fairbanks, Léon Bary, George Siegmann, Eugene Pallette, Boyd Irwin, Thomas Holding, Sidney Franklin, Charles Stevens, Nigel De Brulier,

Willis Robards, Lon Poff, Mary MacLaren, Marguerite De La Motte, Barbara La Marr, Adolphe Menjou.

Synopsis :

"Un pour tous, tous pour un", s'écrient les mousquetaires. Pour d'Artagnan, Athos, Porthos et Aramis, l'honneur de la reine de France est en danger. En butte aux attaques sournoises du cardinal de Richelieu, la Reine doit son salut au dévouement de ces quatre fidèles mousquetaires.

De Paris à Londres, ils devront affronter la sulfureuse Milady de Winter et Monsieur de Rochefort, âme damné du cardinal.

Plaisir de visionnage : Muet (sonorisé), en Noir et Blanc. Long, plus de 2H.

Pas pour tous les publics.

Richelieu est vil, c'est jouissif.

Note : 3 chats.

Disponibilité : Existe en DVD.

Pas disponible sur les plateforme de streaming à ma connaissance.

Gratuit sur Youtube : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R-CRwHGMw6o

Bonus Point Chats : Richelieu a des chatons.

Présents dans des scènes et dans ses bras.

Note : 4 chats.

youtube

0 notes

Photo

Films Watched in 2022:

84. Merry-Go-Round (1923) - Dir. Erich von Stroheim/Rupert Julian

#Merry-Go-Round#Erich von Stroheim#Rupert Julian#Mary Philbin#Norman Kerry#Cesare Gravina#Edith Yorke#George Hackathorne#George Siegmann#Dale Fuller#Dorothy Wallace#Silent Cinema#Films Watched in 2022#My Edits#My Post

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Man Who Laughs | Paul Leni | 1928

George Siegmann and some unfriendly faces...

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Avenging Conscience: or ‘Thou Shalt Not Kill (D. W. Griffith, 1914)

#the avenging conscience#D. W. Griffith#d.w. griffith#edgar allan poe#the tell-tale heart#close up#murder#henry b. walthall#george siegmann#silent film#silent movies

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

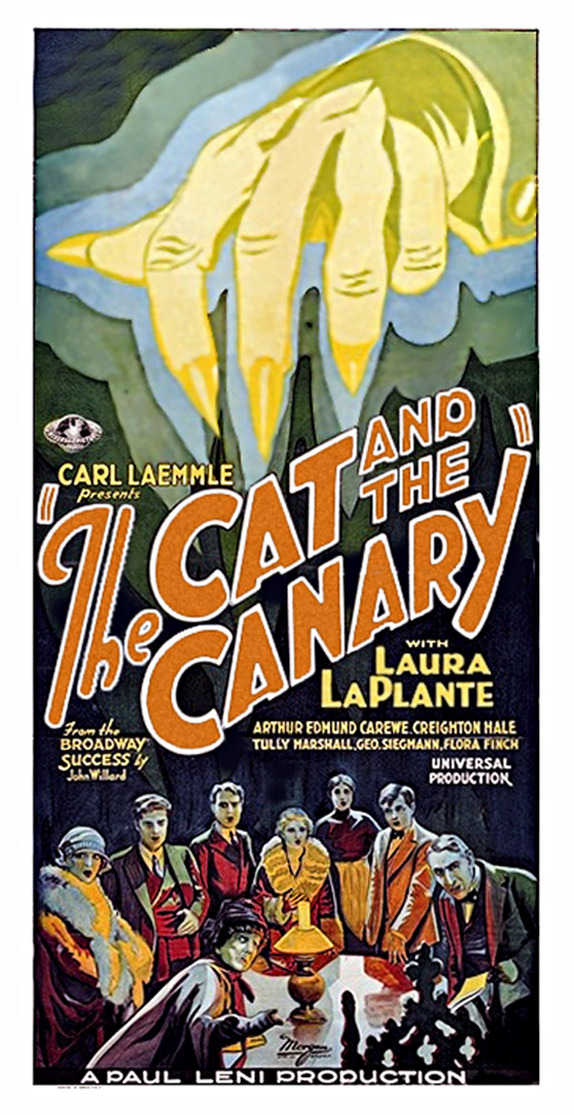

Halloween 2017 movie marathon: The Cat and the Canary (dir. Paul Leni, 1927)

“You must have been lonely these twenty years, Mammy Pleasant.”

“I don’t need the living ones.”

Driven to near-madness and physical decline by his greedy relatives, eccentric millionaire Cyrus West dies in his gothic mansion—however, he orders that his will not be read for another twenty years. Two decades come and go, and a quirky collection of West’s living relatives gather at the mansion to find out who gets the money. The lucky heir is the sweet-natured Annabelle West (Laura La Plante), but before she can claim her inheritance, she must be examined by a doctor who will certify whether or not she is sane. If so, she gets the money, family diamonds, and Cyrus’s creepy but big mansion. If not, she gets an extended stay at an asylum and the money goes to a mysterious runner-up heir, whose identity is sealed away in another envelope. Annabelle is decidedly the sanest of the lot of her bizarre relations, which include her nerdy and stammering cousin Paul (Creighton Hale), snobby and suspicious Aunt Susan (Flora Finch), (Forrest Stanley), the suave but mysterious Doctor (Arthur Edmund Carewe), and the chic but catty (Gertrude Astor), but as the night wears on, her nerves are subjected to unexplained disappearances, murders, and being stalked through the night by what could either be a ghost or an escaped madman from the local mental hospital. Whether the origins of these occurrences are supernatural or crime-related, it becomes clear someone wants to drive Annabelle insane and take her fortune, but who could it be?

Horror didn’t become a cinematic staple in the United States until the enormous success of Tod Browning’s Dracula in 1931; however, there were a few key Hollywood films during the silent era which paved the way for the terrors to come. The Phantom of the Opera is the most celebrated of them as it teems with suspense and gothic set design-- and that’s not mentioning Lon Chaney’s iconic monster make-up which left patrons screaming in the aisles. The Cat and the Canary is the second-most influential pre-Dracula American horror picture. While not as embedded in the popular culture as Phantom, it was one of the biggest hits of its day and remains a favorite of silent film aficionados. The cast sports a host of character actors familiar to lovers of 1910s and 1920s Hollywood cinema, and the visuals—oh Lord, the visuals are the true star, pure gothic expressionism mixed with innovative camerawork that should strike down the idea that all movies were “filmed stage plays” before Citizen Kane.

As you can likely see from the plot summary above, the storyline of The Cat and the Canary will likely appear familiar, even creaky, to contemporary viewers. It’s a classic old dark house mystery, with a bevy of strange characters trapped in a menacing setting, freaking out as things go bump in the night. This film and its 1922 stage play source material are often classified as dark comedy, as there is quite a bit of comic relief throughout due to how weird the characters are and how they react to the mayhem around them. However, the horror elements are strong enough to make this more than your standard drawing room murder-mystery: director Paul Leni and cinematographer Gilbert Warrenton create an uneasy atmosphere from the first scenes where we learn about the death of Cyrus West, how he was driven to his grave by his cruel, avarice-ridden relatives. In a symbolic sequence, we see Cyrus in his pajamas dwarfed by large, double-exposed images of cats baring their fangs and swiping at him with large, clawed paws. It sounds corny when I describe it, but the effect it has when you actually watch it is chilling and effective.

After this prologue, we’re treated to a first-person POV tracking shot through the gloomy corridors of the mansion, curtains flapping about in the wind as the camera glides about in the ghostliest manner before we arrive at the safe where the will lies hidden. As you watch this movie, the one motif which resonates throughout is the image of hands. Hands grasping at jewelry or throats, hands tentatively outstretched, hands breaking through locks and windows—even the paws of the giant, expressionistic cats are part of this visual thread. These images help establish the menace of the situation as well as emphasize the greed that motivates so many of these characters. It’s a little bit of a shame that the plot is so basic in comparison to the elaborate cinematography and expressionistic visual symbolism. It isn’t a bad story by any means and there are several suspenseful moments to be found, one just wishes for a bit more meat or a more interesting protagonist to follow.

Even if the visuals and atmosphere are what make the movie for the most part, The Cat and the Canary is nevertheless a fun and spooky romp, featuring good comic performances from its cast. Laura La Plante was Universal’s most popular female star throughout most of the 1920s, though she is mostly forgotten today; this film remains her most remembered role, if only because the image of the clawed hands grasping at her throat as she sleeps is so iconic. As Annabelle, she isn’t given too much to do other than be bewildered and frightened, though her cool blonde style gives her the feel of a Hitchcock heroine in some scenes. Her thin characterization likely stems from the fact that Annabelle is the de facto everywoman character, the one spot of normalcy among these eccentrics. Even so, one wishes she was allowed to be at least a little bit more unique—though it would be hard to compete with the other actors in this movie. If you’re a silent movie nerd like me, then this movie is a practical who’s-who when it comes to character actors. Creighton Hale, a heart-throb of the 1910s who played Prince Charming in the 1916 Snow White which inspired a fifteen-year-old Walt Disney, plays the nerdy love interest Paul. George Siegmann, most known for his villain parts, is a creepy asylum employee who hopes to get someone in a straightjacket before the night is up. Annabelle’s fashionable flapper cousin Cecily is played by Hal Roach regular Gertrude Astor. My choice for best performance goes to Martha Mattox as the dour housemaid, ironically called “Mammy Pleasant” by the other characters. The only inhabitant of the manor for the past twenty years, she is enamored by her late master and spends much of the time almost savoring the discomfort of the frightened guests. The characters are all broad types rather than fully fleshed out beings, but such an approach fits the material.

The Cat and the Canary was not only a big box office hit, but also a huge influence for later filmmakers, most famously James Whale. Whale’s 1932 horror-comedy The Old Dark House replicates the look of this movie down to the eerie image of curtains billowing in a shadowy hallway. Later on, even Jean Cocteau seems to have mined Leni’s film for visual inspiration in his moody 1946 adaptation of Beauty and the Beast. Just watch that scene where Belle levitates down a corridor with billowing curtains and tell me you don’t get flashbacks to The Cat and the Canary! However, it is Whale’s The Old Dark House to which this film is often compared. To watch the two of them back-to-back could be an interesting experience: the humor in Whale’s film is much quirkier, the inhabitants of the eponymous house far more sinister, and the guests possess more depth on the whole, from Charles Laughton’s bitter widower to Gloria Stuart’s vain yet disillusioned socialite. Still, without Leni’s film, that movie might not be the masterpiece of horror-comedy we know and love now. Whale took the lessons he learned from Leni and pushed them further into weird territory. Yet even so, the camera movements and overlapping imagery in this film are sophisticated, in their own way superior to the later movie. Dammit, both are great—let’s leave it at that!

While the general concept may be dated, The Cat and the Canary is still an impressive film. It’s a lot of fun and the granddaddy of horror-comedy classics to follow, from The Old Dark House to the Evil Dead films. If you wonder why people thought sound films were a fad in the late 1920s, then the dazzling cinematography of even genre pictures like this should give you a good idea as to why.

#halloween 2017#the cat and the canary#silent film#horror#suspense-thriller#mystery#dark comedy#laura la plante#creighton hale#paul leni#1920s#thoughts#martha matox#george siegmann#gertrude astor#expressionism

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

American Culture in the 1910s: The Birth of a Nation (1915)

“If there is one film that stands at the centre of the interrelated developments in the economics, audiences, and the technical and narrative structures of film at this time, it is David Wark Griffith’s Civil War epic of 1915. Civil War pictures enjoyed a vogue in the 1910s, especially in the key fiftieth anniversary years of 1911, 1913 and 1915; ninety-eight such films were produced in 1913 alone.

Griffith, a Kentuckian and the son of a Confederate veteran, had bought the rights to Thomas Dixon’s The Clansman (1905), a successful novel and play which related how the Ku Klux Klan saved the white South from the supposed tyranny of black enfranchisement under radical reconstruction.

(In a deal which contemporary novelists would swoon over, Dixon was paid $2,500 up front for the film rights, and received 25 percent of the profits). Such a sweeping historical project suited Griffith’s enormous ambitions for film; he had chafed at the restrictions at Biograph where, between 1907 and 1913, he had built the studio’s preeminent reputation for quality films with an astonishing and technically innovative body of work.

Indeed, Biograph’s refusal to release Judith of Bethulia, his 1913 epic, partly because he had exceeded their length and budget restrictions without permission, prompted his resignation and signing with Mutual on the agreement that he could make two ‘special’ films per year.

His first was The Birth of a Nation. Costing an unprecedented $60,000 to produce, and an almost equal amount in promotion and legal fees, Griffith’s twelve-reel film was the most costly, lengthy and expensive to see in cinema history up to that time. It was also by far the most successful: by the end of 1917 it had grossed sixty million dollars. The film dramatised the fates of two families, one from South Carolina, one from Pennsylvania, in the years surrounding the Civil War.

The Southern Cameron family, headed by ‘Little Colonel’ Ben Cameron (Henry Walthall), are friendly with the northern Stoneman family, headed by Austin Stoneman (Ralph Lewis), the leader of the Republicans in the House of Representatives. Stoneman – modelled on the proponent of radical reconstruction, Thaddeus Stevens – is portrayed as possessing a variety of disastrous personal weaknesses, including vanity (he wears a wig), a fondness for bombast and, most pointedly, a predilection for his mulatto housekeeper, played by Mary Alden.

Following the war, and the deaths of sons from both families as well as an elaborately staged reconstruction of Lincoln’s assassination at Ford’s Theatre, Stoneman pursues a policy (to quote from Woodrow Wilson’s history of the period, which was used in many intertitles) designed to ‘put the white South under the heel of the black South’. To enforce this he ensures the appointment of Silas Lynch (George Siegmann), his mulatto henchman, as Lieutenant Governor of South Carolina.

Meanwhile, Ben Cameron – recuperating in a northern hospital after heroic deeds on the battlefield – has fallen for Elsie Stoneman (Lillian Gish) who is working as a nurse there. The remainder of the film dramatises the threat to white southerners of this political policy, a threat continually dramatised in sexual terms as black men attempt to rape members of both the Stoneman and the Cameron families. The film’s climax comes as Cameron devises the idea of the Klan, which is hailed as ‘the organization that saved the South from the anarchy of black rule’.

Riding to the rescue at the head of a huge posse of Klansmen, in scenes which had white audiences cheering, Cameron saves his sweetheart Elsie from the clutches of Lynch, and his sister from a horde of black militia. The double marriage at the close of the film sees ‘the former enemies of North and South . . . united again in common defence of their Aryan birthright’. Controversy attended this unvarnished white supremacist propaganda from the start. The National Board of Censorship voted fifteen to eight to pass the film, after insisting on cuts (such as a scene depicting the castration of the most malignant black rapist, Gus, and one showing ‘Lincoln’s solution’ of transporting black Americans back to Africa).

Riots broke out at screenings in Boston and Philadelphia, and the film was denied a release in several major cities. Moreover, the film was a major prompt to the formation of the second Ku Klux Klan in 1915 by William Simmons, a Methodist minister in Georgia. In the 1920s, the Klan would be a major political force for racism, anti-Semitism, anti-Catholicism and nativism, as its numbers swelled to over four million.

Conversely, the film gave a great boost to the national profile of the recently formed National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which led a vigorous protest against the film aided by many sections of the liberal and Progressive media (Francis Hackett in the fledgling New Republic denounced it as ‘aggressively vicious and defamatory’; James Weldon Johnson saw Dixon’s attitude as one of ‘unreasoning hate’). Stung by such criticism, Griffith and Dixon mounted very public defences of the film’s historical accuracy and the principles of free speech in films, a publicity which adroitly fuelled the film’s notoriety and its box office returns.

One of the things which troubled critics most was the film’s astonishing technical virtuosity. ‘As a spectacle it is stupendous’, Hackett noted glumly, a feature which only added to its persuasiveness and ideological force. Indeed, critics who attempt to separate the film’s politics from its technical achievements often overlook the fact that it was precisely these technical achievements that gave those politics both an appeal and a legitimacy to millions of Americans.

The war scenes are epic in scale; and the final ride of the Klan, using tracking shots, dramatic high camera angles, and fast-paced cross-cutting between three different locations, was the apogee of a technique which Griffith had perfected at Biograph (where, as Tom Gunning notes, he had frequently utilised the ‘archetypal drama of a threatened bourgeois household’).

Scenes such as the final ball before the Confederate volunteers leave for war – lit strongly from above and behind, to give the characters a glow suggestive of the imminent destruction of a way of life – are beautifully composed; and, as Eileen Bowser notes, the scene of the Little Colonel’s homecoming, where the camera withdraws its omniscience at the moment he enters his home and his mother’s arms, has an undimmed emotive power.

Yet, like the popular fiction of the era such as Tarzan of the Apes, the popularity of The Birth of a Nation must be partly ascribed to its indulgence of fantasies of sexual dominance. Griffith had even swapped Lillian Gish into the lead role of Elsie Stoneman in place of Blanche Sweet because – as Gish recalled – ‘I was very blonde and fragile-looking. The contrast with the dark man [a blacked-up George Siegmann] evidently pleased Mr. Griffith, for he said in front of everyone, “Maybe she would be more effective than the mature figure I had in mind.”’

A turning point in assessments of the aesthetic and economic potential of features, nonetheless the film’s ability to represent and market with such wild success such a disturbing and reactionary conjunction of race, gender and sexuality is one of the decade’s most disturbing cultural moments.”

- Mark Whalan, “Film and Vaudeville.” in American Culture in the 1910s

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

#The Cat and the Canary#Laura La Plante#Arthur Edmund Carewe#Forrest Stanley#Tully Marshall#Creighton Hale#Gertrude Astor#Flora Finch#George Siegmann#Martha Mattox#Paul Leni#1927

1 note

·

View note

Text

Léon Bary, Eugene Pallette, Douglas Fairbanks and George Siegmann in Fred Niblo’s THE THREE MUSKETEERS (1921)

14 notes

·

View notes

Link

Established as master of war movies, D. W. Griffith took on World War I in Hearts of the World. It was made at the request of the British government in 1917-18, and is as much a propaganda film as a drama, with much newsreel footage thrown in for good measure. But its leads (Robert Harron, Lillian Gish, and Dorothy Gish), its villain (George Siegmann), and an adorable child actor, Ben Alexander (who was to become a poignant, vulnerable soldier in All Quiet on the Western Front twelve years later), help greatly to put it over. And it also offers a glimpse of Noel Coward, age eighteen, pushing a wheelbarrow through a French village street.

#DW Griffith#lillian gish#dorothy gish#robert harron#noel coward#film review#film criticism#1994#lawrence quirk

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Marion Davies and Owen Moore in The Red Mill (Roscoe Arbuckle, 1927)

Cast: Marion Davies, Owen Moore, Louise Fazenda, George Siegmann, Karl Dane, Russ Powell, Snitz Edwards, William Orlamond, Ignatz. Screenplay: Frances Marion, titles by Joseph Farnham, based on a musical by Victor Herbert and Henry Martyn Blossom. Cinematography: Hendrik Sartov. Art direction: Cedric Gibbons, Merrill Pye. Film editing: Daniel J. Gray. Music: Michael Picton.

The Red Mill was directed by Roscoe ("Fatty") Arbuckle under the pseudonym “William Goodrich” that he adopted after being blacklisted in the "wild party” scandal over the death of Virginia Rappe, even though he was acquitted. It's a fairly forgettable romantic farce, about Tina (Marion Davies), a Dutch scullery maid, who falls in love with Dennis (Owen Moore), an Irishman visiting Holland, and gets involved with a plot to save Gretchen (Louise Fazenda) from having to marry someone other than her boyfriend Jacop (Karl Dane). Very loosely based on a creaky old Victor Herbert operetta, it's a surprisingly well-preserved silent film, with crisp images -- the cinematography is by Hendrik Sartov, a Danish director of photography who also shot the Lillian Gish films La Bohème (King Vidor, 1926) and The Scarlet Letter (Victor Sjöstrom, 1926). Given that it's a fitfully amusing comedy, whose chief virtue is that is shows off the great comic gifts of Davies, it might be surprising to find it in such pristine condition when so many other (and better) silent films are available only in patched-together restorations or have been lost altogether. The reason is probably that it was produced by William Randolph Hearst's company, Cosmopolitan Productions, which existed largely to showcase Davies, Hearst's mistress. So MGM, which released the film, took special care not to offend Hearst in its handling of The Red Mill. Davies is, as so frequently, a delight, playing physical comedy without sacrificing her beauty and femininity. She does a wonderful slapstick bit in which she tries to solve the problem of assembling a folding ironing board -- a twist on the familiar struggles of comedians with folding beach chairs. But Arbuckle, who directed dozens of short films, doesn't give this movie the pace needed to sustain itself at feature length. Joseph Farnham is responsible for the cornball captions -- sample: "A summer on Holland's canals leaves an impression, but a fall on its ice leaves a scar."

5 notes

·

View notes