#Georg bredig

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

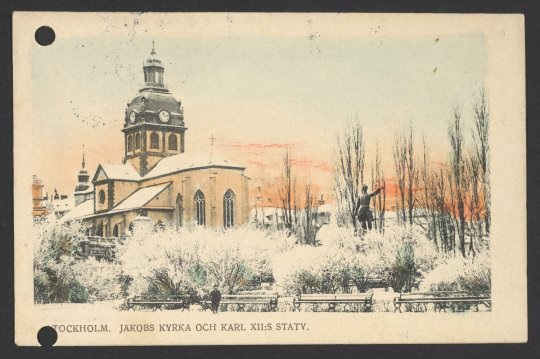

Oh, how I wish Philly was covered in snow like this postcard of Stockholm, Sweden.

It's been a while since we've seen a good old fashioned snow storm here in the city. Maybe I'll sleep with my pajamas on inside out tonight....

Image citation: Arrhenius, Svante. “Postcard from Svante Arrhenius to Georg Bredig, June 1911,” 1911. Papers of Georg and Max Bredig, Box 1, Folder 5. Science History Institute. Philadelphia.

#snow#i want snow#holidays#winter#snow in the city#philadelphia#philly#philly philly#postcards#bredig collection#archives#from the archives#special collections#digital collections#othmeralia

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Un cuadro de Tenerife pintado por el premio Nobel Wilhelm Ostwald

El cuadro que se ve sobre estas líneas fue pintado en 1913 por el fisicoquímico alemán Wilhelm Ostwald (1853-1932). Representa un paisaje costero de Tenerife (Islas Canarias). La esposa de Ostwald, Helene, se lo regaló en 1933 al también fisicoquímico Georg Bredig, ya que este y Ostwald habían sido muy buenos amigos. Nota en la parte posterior del cuadro de Ostwald (digital.sciencehistory.org,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

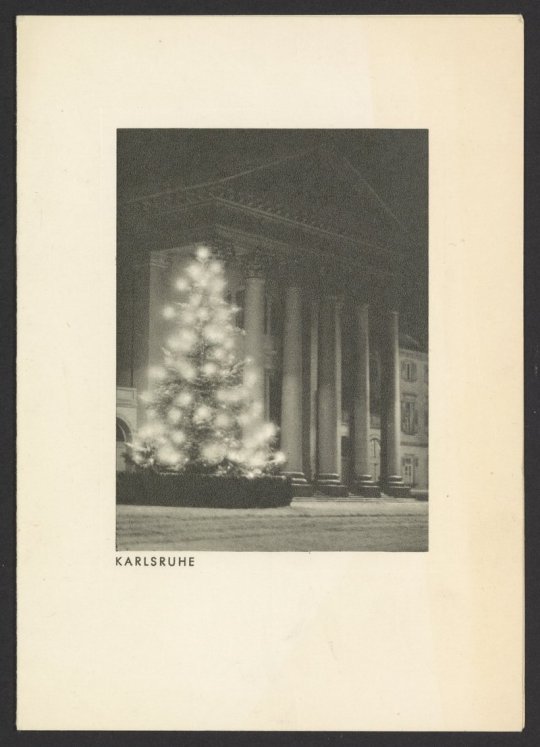

O Christmas Tree, O Christmas Tree!

A Christmas card featuring a black and white illustration of a large adorned Christmas tree at the Rondellplatz, or the city square of Karlsruhe, Germany.

Image citation: Ruzek, Joseph. “Christmas Card from Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Ruzek to Georg Bredig,” n.d. Papers of Georg and Max Bredig, Box 2, Folder 47. Science History Institute. Philadelphia.

#christmas#christmas tree#bredig papers#georg bredig#archival collection#archives#image archives#photo archives#tannenbaum#holidays#happy holidays#german scientists#othmeralia

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

April 12: On this Day in History in the Bredig Archives, Svante Arrhenius writes about Cosmic Physics

The winner of the 1903 Nobel Prize for Chemistry and a founding member of the Nobel Institute, Svante Arrhenius (1859-1927) was a multifaceted Swedish scientist whose research endeavors included physical chemistry, cosmic physics, and immunologic chemistry.

Arrhenius’ work in the new field of physical chemistry in the late 19th and early 20th centuries comprised the early years of his career. As a doctoral and postdoctoral student in his native Sweden, and at laboratories in Latvia and Germany, he worked on electrolytes and in 1889, developed the Arrhenius equation, a mathematical expression describing the effect of temperature on the velocity of a chemical reaction. Around this same time while working at Wilhelm Ostwald’s laboratory at the University of Leipzig, Arrhenius also became acquainted with Georg Bredig, who would become an eminent physical chemist in his own right. Over the next four decades, the men corresponded about their lives, scientific endeavors, developments, and achievements, as well as world affairs.

Several of Arrhenius’ letters to Bredig provide keen insight and detail into his later work outside of physical chemistry. In a letter dated April 12, 1914, for example, Arrhenius tells Bredig of his recent trip to Norway to speak about his interest in “cosmogony”:

“Thank you for your kind letter from March 26th. On this day, I returned from a three-week trip in Norway, where I lectured on Cosmogony in Trondheim and Bergen. The reception committees were very welcoming, and the audiences were extremely interested….It is very encouraging to witness the keen interest of the audience.”

Cosmogony, which is derived from the Greek words “kosmos” and “genesis”, refers to theories or myths concerning the creation of the universe. Arrhenius attention to the subject most likely resulted from his work in cosmic physics and the concept of “panspermia”, the notion that life evolved on earth from spaceborne spores. Arrhenius would later write two popular books on the subject: Worlds in the Making (1908) and The Destinies of the Stars (1918). To read more about the life and work of Svante Arrhenius, as well as his letters to Georg Bredig, visit the Papers of Georg and Max Bredig in the Digital Collections of the Science History Institute.

By: Jocelyn McDaniel, Research Curator of the Bredig Archive

#othmer library#arrhenius#bredig papers#physics#astronomy#cosmos#galaxies#solar system#cosmic physics#georg bredig

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scientist Spotlight in the Bredig Archives: Robert Koch, German Microbiologist, Physician, and Nobel Prize Winner

In February 1901, Georg Bredig, a physical chemist working in the laboratory of Wilhelm Ostwald in Leipzig, Germany, sent a copy of his habilitation thesis “Anorganische Fermente” (Inorganic Ferments) to the eminent German microbiologist and physician, Robert Koch (1843-1910), which Koch later thanked him for. A habilitation is the procedure to achieve the rank of professor in many European countries, including in the German speaking lands of Bredig’s time.

Together with Louis Pasteur, Robert Koch is regarded as one of the founders of modern microbiology, particularly for his discovery of various causes of infectious diseases such as cholera, tuberculosis, and anthrax. For his work on tuberculosis, Koch received the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1905. To learn more about Robert Koch, you can read his biography and view a photographic reproduction of his portrait in the digital collections of the Science History Institute.

#robert koch#nobel prize winners#microbiology#papers of georg and max bredig#georg bredig#habilitation thesis

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

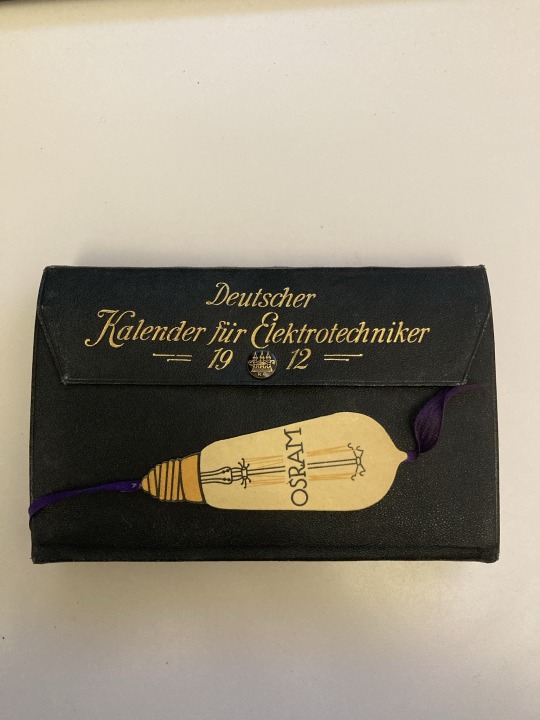

I wish all books would come bound like tiny briefcases from now on.

The Othmer Library recently acquired the archival collection of Georg and Max Bredig, father and son German-Jewish chemists who immigrated to the United States as World War II was threatening their livelihood in Germany.

The archival collection included tons and tons of books and journals that have made their way into our modern collection, and we are just chuffed about it! Pictured above is Deutscher Kalender für Elektrotechniker. We are still in the process of cataloging this donation and will update this post later on with a link to it's record!

#journals#papers of george and max bredig#max bredig#Georg bredig#german books#German scientists#german jewish scientists#journal collection#othmeralia

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Nobel Institute and the Nobel Prize

On January 2nd, 1896, Svante Arrhenius wrote a postcard to his dear friend Georg Bredig, telling him the latest news of the great Nobelian fortune. Arrhenius further says that this fortune, left by Alfred Bernhard Nobel, will be put in a fund to "be used to reward scientific work from around the world."

This fund became the Nobel prize, awarded for Physics, Chemistry, Physiology or Medicine, Literature and Peace. Below is an excerpt from Alfred Nobel’s will, which describes the Nobel prize and each of its categories.

“All of my remaining realisable assets are to be disbursed as follows: the capital, converted to safe securities by my executors, is to constitute a fund, the interest on which is to be distributed annually as prizes to those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The interest is to be divided into five equal parts and distributed as follows: one part to the person who made the most important discovery or invention in the field of physics; one part to the person who made the most important chemical discovery or improvement; one part to the person who made the most important discovery within the domain of physiology or medicine; one part to the person who, in the field of literature, produced the most outstanding work in an idealistic direction; and one part to the person who has done the most or best to advance fellowship among nations, the abolition or reduction of standing armies, and the establishment and promotion of peace congresses. The prizes for physics and chemistry are to be awarded by the Swedish Academy of Sciences; that for physiological or medical achievements by the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm; that for literature by the Academy in Stockholm; and that for champions of peace by a committee of five persons to be selected by the Norwegian Storting.”

The first Nobel Prize would not be awarded until 1901. In 1903 Arrhenius would be the third person to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his electrolytic theory of dissociation.

In March 1905, Arrhenius wrote to Bredig that the Nobel Institute for Physics and Chemistry would open on October 1st, 1905. While the Nobel Institute opened in October 1905, the actual building wouldn't open its doors until May 1906. Because of this, the Nobel Institute of Physics and Chemistry met at Svante Arrhenius’s home.

In this letter, he writes about his hopes and goals for physical building. He says that the building has three floors, the first will be the institute, the second will be meeting rooms for the committee members, and the third will be for assistants and servants.

In Letter from Svante Arrhenius to Georg Bredig, February 1905 , Arrhenius tells Bredig of the modest conditions that Meyerhoffen and Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff (1852 – 1911) work in. he provides measurements of the rooms and even comments on the poor lighting. He uses this as an example of what he does not want at his new institution and says that his laboratory will be “significantly better.”

Arrhenius continues to write to Georg Bredig about the institute through his life. Check out the digital collections for more Arrhenius letters in the archive!

#othmeralia#Svante Arrhenius#Georg Bredig#Nobel Institute#nobel prize#German Chemists#Swedish Chemists#fragments#notebooks#antique#Papers of Georg and Max Bredig

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Celebrating 10K Records Published to the Science History Institute’s Digital Collections!

The Science History Institute is excited to announce that our digital collections have reached a milestone of 10,000 published records. Our 10,000th record is a postcard dated January 6, 1913, from Nobel Prize-winning chemist Walther Nernst to German Jewish scientist Georg Bredig. The postcard is part of the Papers of Georg and Max Bredig, a collection smuggled out of Nazi Germany that tells the story of the pioneering scientist’s rise to prominence and the Bredig family’s struggle to survive the Holocaust. It was recently digitized and translated as part of the Institute’s ongoing Science and Survival project, which is funded by a Council on Library and Information Resources grant.

The translation is as follows:

W. N. Berlin, 6 January 1913 Am Karlsbad 26a

Dear colleague, Thank you for your kind note yesterday. I look forward to your visit very much. I would be extremely grateful if you could let me know a few days in advance so that I will be free. See you soon!

Yours faithfully,

W. Nernst

#othmeralia#digital collections#libraries#scientists#german jewish scientists#Georg Bredig#Walther Nernst#science and survival

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why settle for being just a Baroness-Professor when you can be a Princess-Professor?

Think big, friends! Margarete von Wrangell (1877-1932) was an agricultural chemist and Germany's first female full professor. She married her childhood friend, Prince Vladimir Andronikov, in 1925. This marriage gave her the title of Princess Andronikov, which was a an addition to her title at birth, Baroness von Wrangell.

This article, in German, mentions that the marriage gave her Russian citizenship. Take a peek on our digital collections site.

#women in stem#women scientists#women professors#biology#princesses#princess#baronesses#baroness#chemistry#agricultural chemistry#german scientists#archives#papers of georg and max bredig#othmer library#othmeralia

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

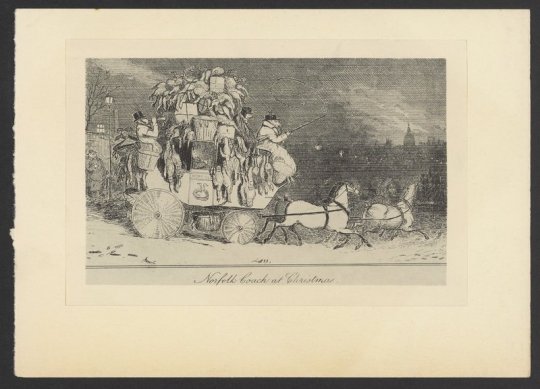

Norfolk Coach at Christmas

Reproduction of a print by artist Robert Seymour (1798-1836) originally completed circa 1820. The Norfolk Coach depicts a horse-drawn carriage being pulled through snowy streets and piled high with pheasants.

Image citation: Seymour, Robert. “Norfolk Coach at Christmas.” New York, New York: New York Public Library, n.d. Papers of Georg and Max Bredig, Box 10, Folder 7. Science History Institute. Philadelphia.

#christmas#science history institute#bredig archives#photo archives#archival collections#archives#max and georg bredig#bredig#othmeralia

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Liegnitzer Bomben in the Archives!

Postcard from Svante Arrhenius to Georg Bredig, January 1896

In 1896 Svante Arrhenius thanked Georg Bredig for sending him Liengnitzer Bomben. Liegnitzer Bomben, also known as Legnica bombs or legnickie bomby, are small cakes made out of gingerbread and filled with fruit and marzipan. They were made to be Christmas treats or souvenirs of visitors from other cities.

Von SKopp - Eigenes Werk, CC BY-SA 3.0

The bombs were first made by the Müller brothers in 1853, but there is a fable associated with the recipe. According to legend, the recipe was presented to a baker by a mountain spirit in a dream. The baker had dreamed of making a famous dessert for Legnica. The mountain spirit, Rübezahl, gave the recipe to the baker. As the baker read the recipe gnomes appeared and started baking the bombs. When the baker woke up the kitchen was filled with freshly baked bombs and the recipe was written down, signed by Liczyrzepa, the mountain spirit.

The recipe has been a coveted secret after World War II and was patented so that it could not be shared. It is kept at the Copper Museum in Legnica and until recently it was not public.

Below is the original recipe translated from Polish

Liegnitzer Bomben (Legnica bombs)

Cake:

500 g flour

400 g honey

250 g sugar

200 g apricot jam

150 g butter

125 g chopped almonds

50 g chopped lemon jelly in frosting

50 g chopped orange jelly in frosting

125 g raisins

2 tablespoons cocoa

1 teaspoon gingerbread spices

4 ml rum

4 eggs

1 packet baking powder

margarine for greasing

breadcrumbs for sprinkling

For the topping:

200 g of chocolate

Preparation:

Melt honey, fine sugar and butter while stirring, then leave to cool. Eggs with cocoa, almonds, gingerbread spice and rum. Mix it with baking powder, flour and add the cooled honey mixture to it, mix.

Mix the washed, dried raisins with finely chopped marzipan, orange jelly, lemon jelly and jam. Instead of apricot jam, you can also use 100 g of small, baked, candied pineapples for the filling.

Grease 12 bomb molds and sprinkle with breadcrumbs. Half-fill the dough, put the marzipan mass on it and cover with the rest of the dough. Bake in an oven preheated to 350 degrees for about 30 minutes. Melt the chocolate glaze and spread on the Legnica bombs.

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

As we're working through cataloging much of our Max and Georg Bredig Collection we find gems like this!

This book is Kleine fabel für meine geige (1933). It has not been cataloged yet but will be soon! Check back for updates.

The archive bib record is found here, which has links to the finding aid and the EAD version. You can also head to our digital collections site to see everything we've digitized in this collection so far! Spanning the years 1891 to 1947, this collection consists of photographs, correspondence, and manuscript materials chronicling the life and career of prominent German-Jewish physical chemist Georg Bredig (1868-1944) and, to a lesser extent, his son Max.

#papers of george and max bredig#scientists#beautiful books#german books#german scientists#history of science#othmer library#othmeralia

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

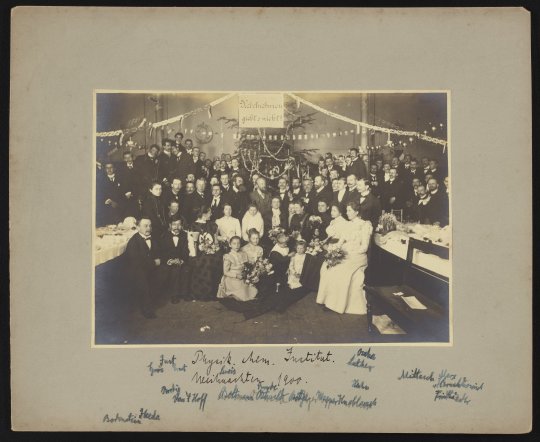

Christmas in the Papers of Max and Georg Bredig!

Merry Christmas from the team working on the Papers of Max and Georg Bredig!

Christmas card from Ilse Wolfsberg to Max Bredig, December 11, 1942. At this time Max Bredig and Ilse Wolfberg were fighting for the release of their friend Fritz Hochwald from a concentration camp in Spain. They never took a break from their mission, even during the holiday season.

University of Leipzig physical chemistry department Christmas party, 1900. This photograph features a large group at a Christmas party. The room is decorated is for Christmas with banquet tables set for a meal.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

A fun game the archivists at the Science History Institute get to play sometimes is "Match the scientist to the signature!". So far in this postcard we have identified.

Mario Betti, 1875-1942

Paul Peter Ewald , 1888-1985

Robert Robertson,

John Richardson Marrack , 1886-1976

James Riddick Partington, 1886-1965

F. G. (Frederick George) Donnan , 1870-1956

Lucas, R

Let us know if you can identify anyone! This postcard, addressed to Georg Bredig, is part of the Papers of Georg and Max Bredig. It was signed by attendees of a scientific conference in London, 1930.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

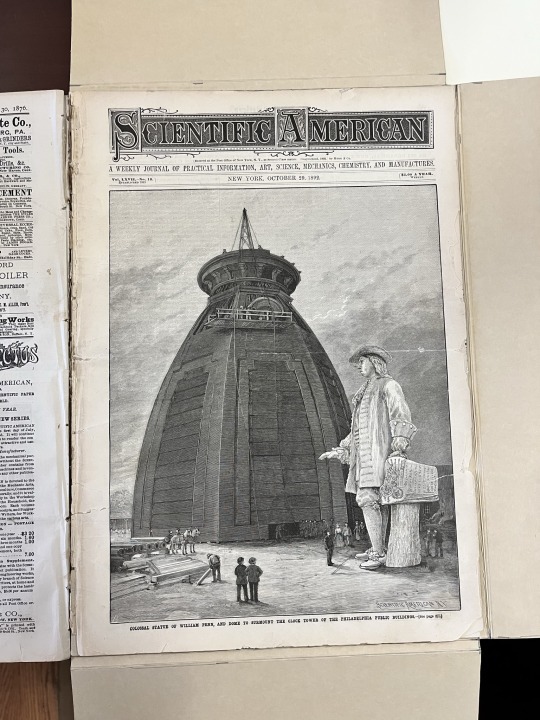

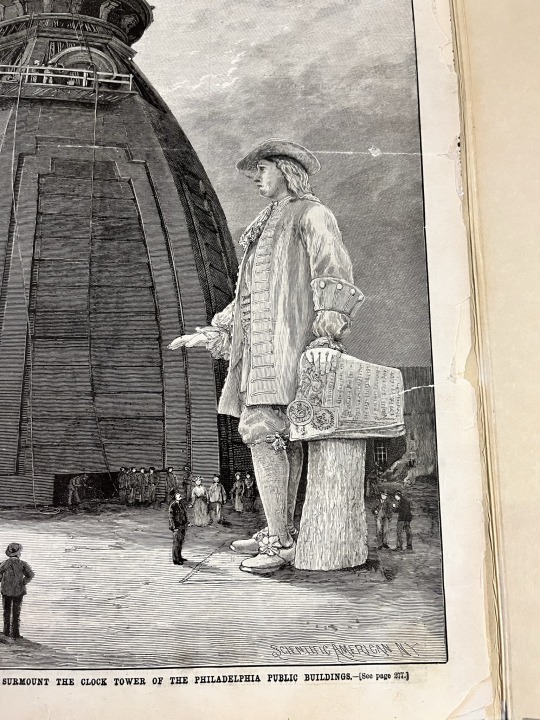

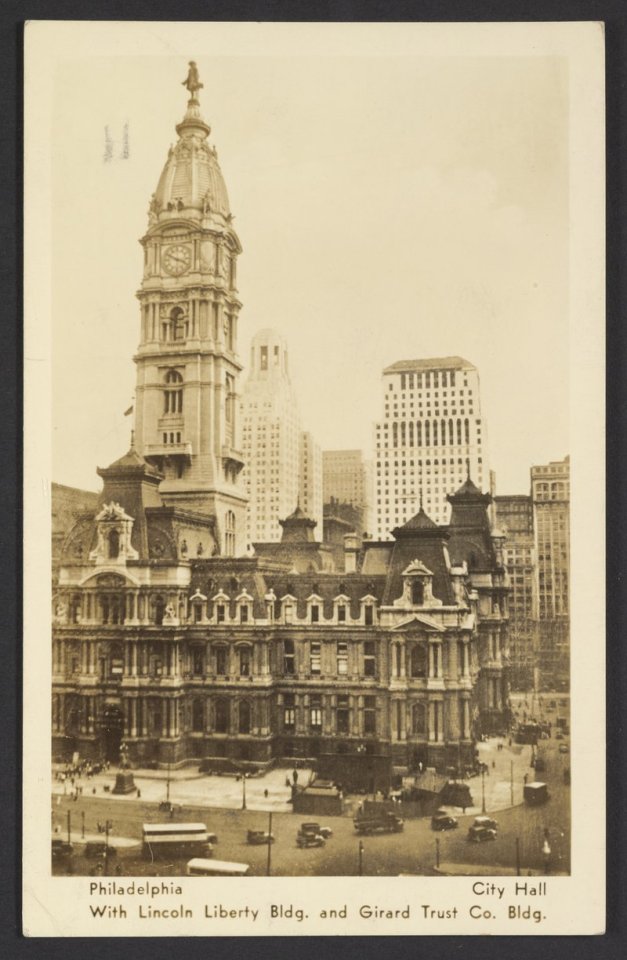

The Curse of Billy Penn

Did any of our followers know that there is a statue of William Penn on top of Philadelphia's City Hall?

We recently picked up a few new (to us) copies of Scientific American, a science and technology journal, from a local library (shout out to The Union League!). One issue features the statue of William Penn, founder of Pennsylvania (though it is important to note that Philadelphia specifically is the ancestral home of the Lenni Lenape or Lennapehoking people), before it was placed on top of Philadelphia City Hall.

William Penn was the product of Alexander Milne Calder, a Scottish-American sculptor, and is 37 feet tall.

For almost 90 years there was an unwritten agreement or understanding that forbade any building in the city from rising above William Penn. This agreement ended when Liberty Place was approved and built in 1987 causing the Curse of Billy Penn to cause disaster on all Philadelphia sports-teams. Pre-1987 Philadelphia sports teams enjoyed a run of success. Post-1987, the curse held on to the city so tightly until the Philadelphia Phillies won the World Series in 2008.

How did the curse end? Well it did and then didn't. The Comcast Center was built in 2007 and a few iron workers decided to place a tiny statue (about 4 inches tall) on top to make William Penn, yet again, the tallest figure in the city. The Philadelphia Phillies won the World Series in 2008, breaking the curse.

Then! In 2017, a new building became the tallest building in Philly. A second Comcast Center. Once again, iron workers placed a tiny Billy Penn on top... the Philadelphia Eagle went on to absolutely crush the New England Patriots in the 2018 Super Bowl. Go birds!

Photo credit: Höber, R. “Postcard from R. Höber to Georg Bredig,” April 23, 1935. Papers of Georg and Max Bredig, Box 1, Folder 59. Science History Institute.

#philadelphia#philadelphia history#philadelphia eagles#william penn#curse of billy penn#scientific american#sculpture#history#science history#local history#go birds#eagles#digital collections#libraries#libraries of tumblr#special collections#journal collection#alexander milne calder#othmer library#scientific illustration#othmeralia

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

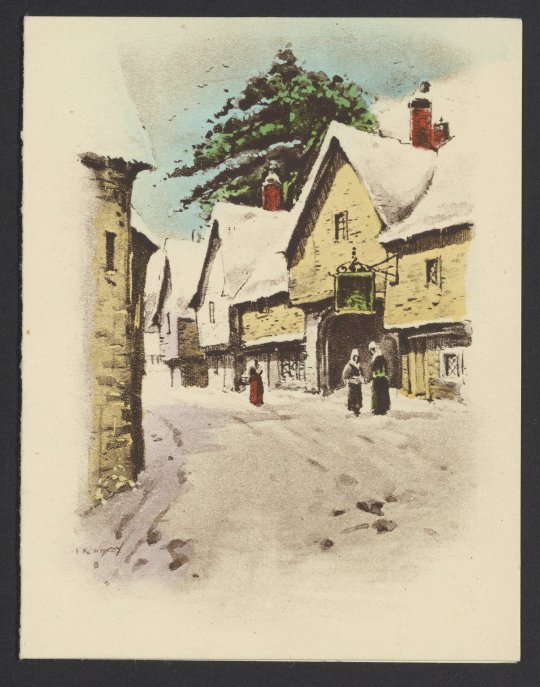

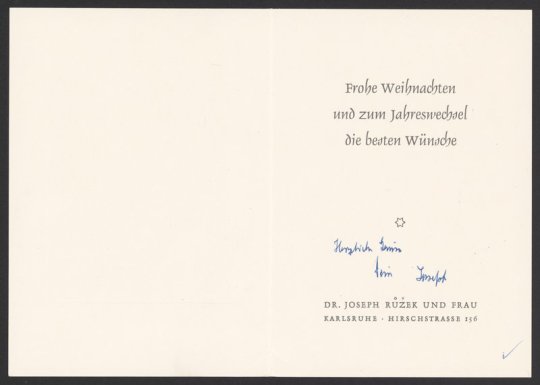

Holiday card from Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Ruzek to Georg Bredig

A Christmas card featuring a black and white illustration of a winter nighttime scene. The view shows a snow-covered Karlsruher Schloss, or Karlsruhe palace.

Here's a transcription of the German written on the back of the postcard:

Frohe Weihnachten und zum Jahreswechsel die besten Wünsche

Herzliche Grüsse Dein Joseph

Dr. Jospeh Ruzek und Frau KARLSRUHE – HIRSCHSTRASSE 156

Here is the English translation:

Merry Christmas and Best Wishes for the New Year!

Warm Regards Joseph

Dr. and Mrs. Jospeh Ruzek KARLSRUHE – HIRSCHSTRASSE 156

Image citation: Ruzek, Joseph. “Holiday Card from Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Ruzek to Georg Bredig,” n.d. Papers of Georg and Max Bredig, Box 2, Folder 47. Science History Institute. Philadelphia.

#christmas#german#scientists#german scientists#ephemera#illustrations#Karlsruhe#Bredig Papers#Archival collections#archives#image archives#othmeralia

11 notes

·

View notes