#Georg Spalatin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"As for Spalatin, he quickly found favor with Frederick, soon gaining his deepest confidence."

Quote selected randomly from page 79 of Eric Metaxas's biography Martin Luther: The Man Who Rediscovered God and Changed the World.

Quote was selected at random from a book chosen at random from the Willowick Public Library.

#Books#Nonfiction#Biography#Quotes#Martin Luther#Eric Metaxas#George Spalatin#Frederick the Wise#The Protestant Reformation#The Willowick Weeks

0 notes

Text

oh my fucking god

your name is Martin Luther. you have just been tried and convicted for heresy. luckily your buddy Frederick Elector of Saxony "kidnapped" you on the road to protect you from the Pope's justice. it would seem to be very important for you to keep a low fucking profile! do NOT let people know where you are!!!

and yet,,,,

Not for the first time, therefore, Luther determined on a ruse to fool his enemies—and like many of his other cunning plans, this one was a little too clever. He wrote to [his friend and mentor] Spalatin in mid-July 1521 enclosing another letter in his own hand, that purported to have been sent from "my quarters" in Bohemia. He asked Spalatin to "lose" it "with studied carelessness": "I hear a rumor is being spread, my Spalatin, that Luther is living in the Wartburg near Eisenach . . . Strange that nobody now thinks of Bohemia," he wrote. He "would love the 'hog of Dresden'" (that is, Duke Georg) to find the letter, Luther wrote in his accompanying note. It was obvious that the letter has no point apart from where it was supposedly sent. It would have fooled nobody. Worse, for many, it would have confirmed that he was indeed in the Wartburg, the letter too eager to deny the rumor in the first line.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

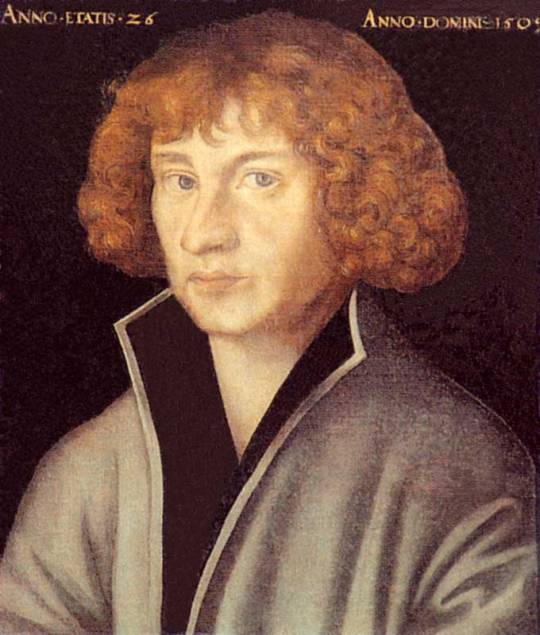

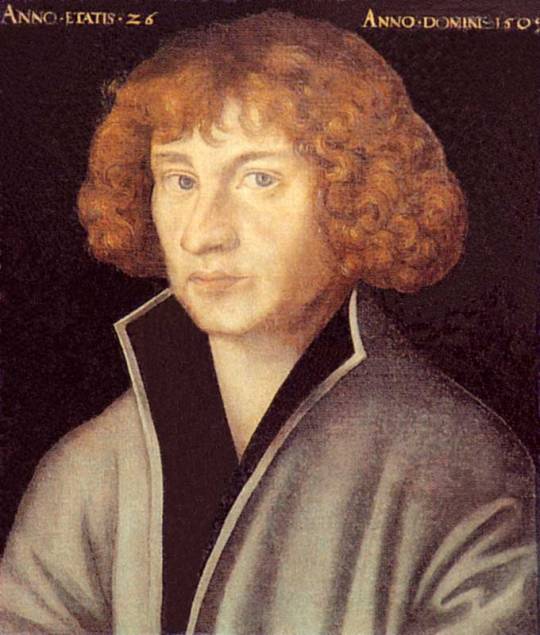

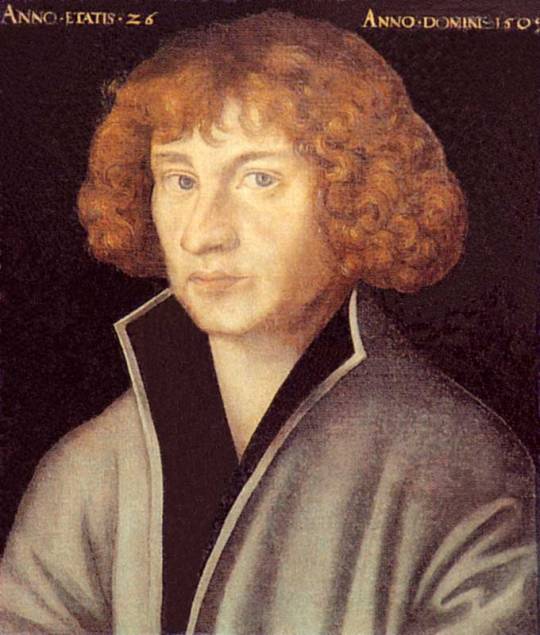

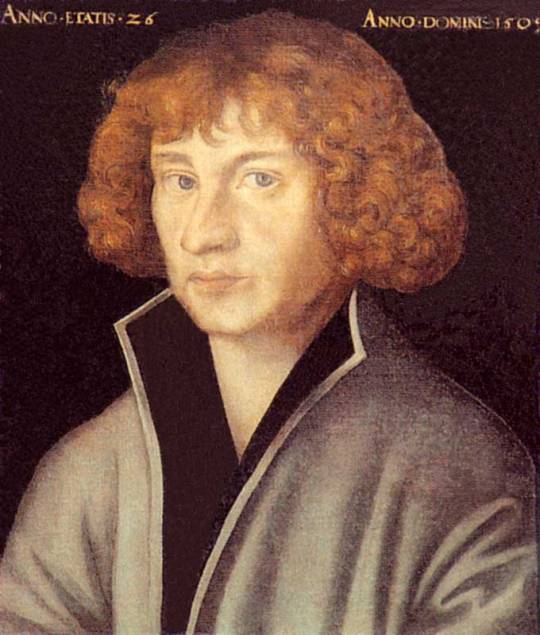

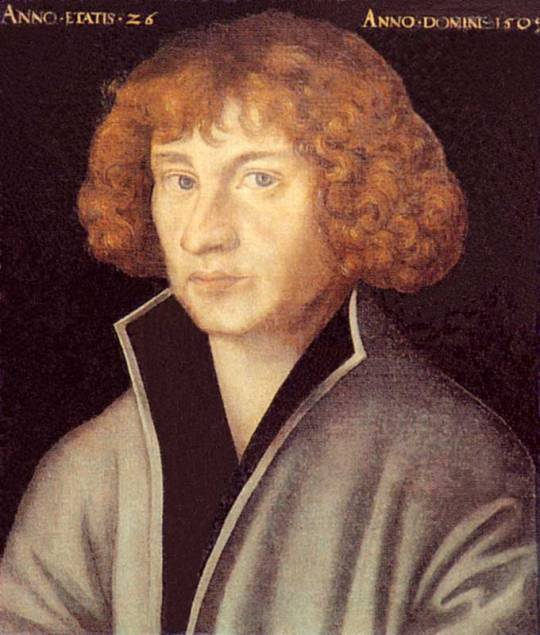

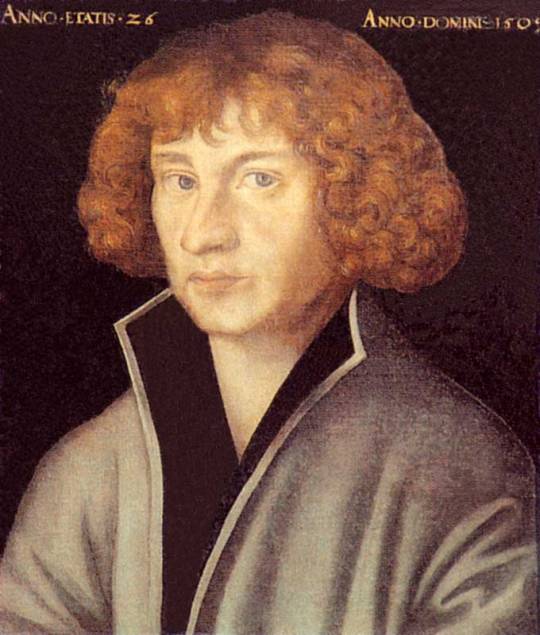

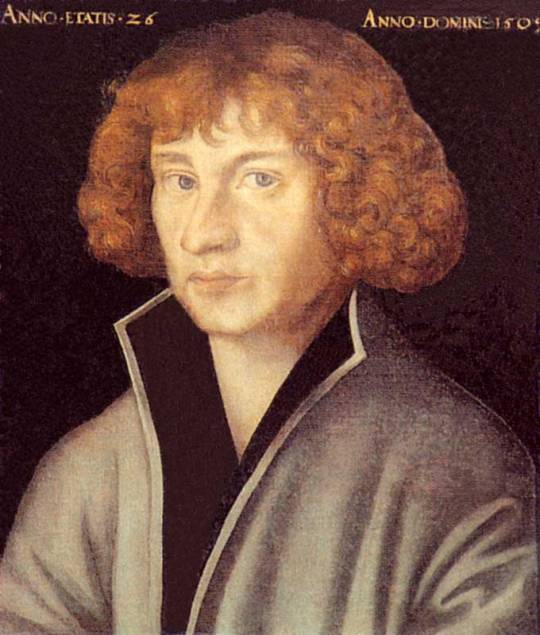

Title: Georg Spalatin

Artist: Lucas Cranach the Elder

Date: 1509

Style: Northern Renaissance

Genre: Portrait

#art history#art#painting#artwork#history#museums#culture#vintage#curators#classicalcanvas#northern renaissance#portrait#lucas cranach the elder

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

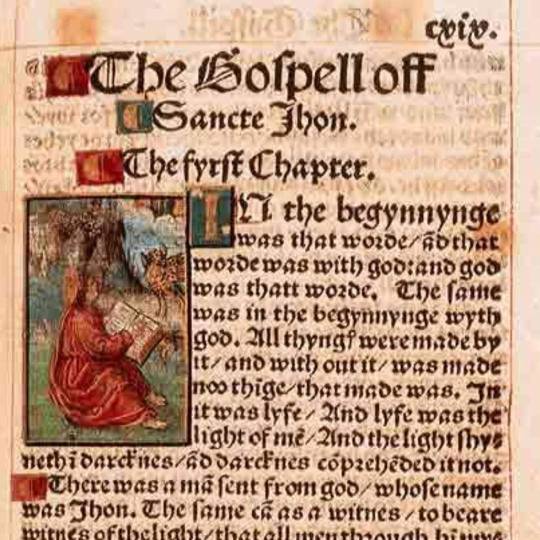

LA PUBLICATION DE LA BIBLE EN ANGLAIS

En 1524, Tyndale quitte sa patrie qu'il ne reverra plus. Se rendre dans le Saint Empire lui permet d'avoir accès à l'étude de l'hébreu, car en Angleterre l'Édit d'Expulsion (1290) interdisait la détention de livres en hébreu en Angleterre. Mais en ce début de XVIe siècle, les écrits en grec ancien devenaient, pour la première fois depuis des siècles, accessibles à la communauté savante d'Europe. Fort des manuscrits rendus disponibles par la diaspora des érudits byzantins depuis la Chute de Constantinople (1453), Érasme venait de traduire et d'éditer, sous le titre (énigmatique) de « Novum Instrumentum » le texte grec des Saintes Écritures, dépassant la Vulgate.

H. Samworth suggère d'interpréter l'immatriculation d’un certain Guillelmus Daltici ex Anglia, présente dans les registres de l’Université de Wittemberg comme celle de William Tyndale. Ce pourrait donc être à Wittemberg que Tyndale paracheva sa traduction du Nouveau Testament, en 1525, avec l'aide du frère minorite William Roy.

Il remet sa traduction à l’imprimeur Peter Quentell, de Cologne, mais l'entrée en vigueur des mesures anti-luthériennes dans cette ville stoppe net la publication : des ouvriers trop bavards auraient informé le prêtre Cochlaeus, l'un des principaux adversaires de Luther. Tyndale se précipite à l'atelier, saisit ses précieux manuscrits et les emporte à Worms, ville libre d'Empire alors en voie de conversion à la Réforme. Il faut attendre l'année suivante pour voir la parution du Nouveau Testament par l'imprimeur Peter Schoeffer de Worms.

De nouveaux exemplaires parurent bientôt à Anvers. On ignore à quel moment au juste Tyndale était parti pour le port d'Anvers; à la date du 11 août 1526, on lit dans le journal de Georg Spalatin que Tyndale est resté à Worms près d'une année entière.

Cochlaeus alerte cependant l'évêque Tunstall, qui interdit les bibles en octobre 1526. Tyndale sait donc que les précieux volumes seront saisis à leur arrivée en Angleterre. Pour déjouer l'étroite surveillance qui s'exerce dans les ports, les Nouveaux Testaments sont cachés dans des ballots d'étoffe ou des barils de vin. Beaucoup d'exemplaires sont néanmoins confisqués. Leurs destinataires sont astreints à défiler à cheval, le visage tourné vers la queue de l'animal, et portant visiblement le livre défendu ; ils devront le jeter eux-mêmes au feu devant tous et faire pénitence. L'historien du protestantisme Richard Marius avance que « le spectacle des Ècritures enflammées par une torche (...) déchaîna la controverse même parmi les fidèles. » Mais les efforts de l'évêque de Londres sont voués à l'échec. Les Londoniens veulent prendre connaissance de l'ouvrage proscrit et s'ingénient à l'obtenir au mépris des menaces. En désespoir de cause, l'évêque de Londres prie Packington, un négociant de la cité, de mettre à profit ses relations commerciales avec le port d'Anvers, pour accaparer à la source toute l'édition de Tyndale. Muni d'une forte somme d'argent, Packington se rend sur le continent. L'évêque a cru « mener Dieu par le bout du doigt », écrit un chroniqueur de l'époque. Mais il ne réussira pas mieux dans cette entreprise que dans les précédentes. Packington, ami secret de Tyndale, arrive chez le traducteur :

« Monsieur Tyndale, je vous ai trouvé un bon acquéreur pour vos livres,

- Et qui donc ?

- L'évêque de Londres !

- Mais, si l'évêque veut ces livres, ce ne peut être que pour les brûler !

- Eh bien qu'importe ! D'une manière ou d'une autre l'évêque les brûlera. Il vaut mieux qu'ils vous soient payés ; cela vous permettra d'en imprimer d'autres à leur place ! »

Le marché est conclu et l'édition est apportée en Angleterre. L'évêque de Londres convoque la population devant la cathédrale Saint-Paul pour assister à la destruction massive des livres hérétiques. Cependant, le bûcher de l'évêque devient une publicité inespérée pour la deuxième édition du Nouveau Testament Tyndale. Imprimé cette fois en petit format, pour faciliter la dissimulation des volumes et mieux échapper aux perquisitions, sa diffusion est un vif succès. Le cardinal Wolsey condamna Tyndale comme hérétique, et le premier procès en hérésie s'ouvrit en 1529.

Tyndale serait retourné à Hambourg vers 1529, emmenant son manuscrit. Il y révisa son Nouveau Testament et commença à traduire l'Ancien Testament, non sans travailler à d'autres essais.

0 notes

Text

“Anna of Saxony was born on November 22, 1532 at Hadersleben, Denmark to Dorothea of Saxony-Lauenburg and Christian III, the future king of Denmark. She married Duke August of Saxony on October 7, 1548 at Torgau, Saxony, and when he inherited the title Elector of Saxony in 1553, she became the electress. Anna died on October 1, 1585 at Dresden. Her library, which was located in the women’s quarters of the residential castle at Annaburg, Saxony, contained 500 titles in 438 volumes—arranged according to size on the shelves—and approximately 50 manuscripts. Shortly before Anna’s death, an inventory was taken of the medical manuscripts located in a special cabinet in her library by Abraham von Thumbshirn, an electoral Saxon councilor and the superintendent of Anna’s court.

After her death, another inventory was taken of the printed books and manuscripts in her library by Sebastian Leonhart. Together with Elector August’s 2,354 volumes in his apartments at Annaburg, Anna’s collection formed the core of the later Royal Saxon Library. The large number of German territories in the early modern period meant that court libraries played a greater role than in other countries. Lay collectors achieved personal prestige through ownership of an identifiable corpus of artifacts that allowed them to gain a physical and intellectual understanding of the rapidly changing world during the age of exploration.

Indeed, the libraries of the elector and the electress must be seen in the broader framework of their other dynastic collections, including the Armory and Saddlery (Rüst- und Harnischkammer), the cabinet of coins and medals (Münzkabinett), the collection of silver plate (Silberkammer), the treasury (Schatzkammer), and the seven-room “cabinet of curiosities” (Kunstkammer). The Kunstkammer was perhaps the second oldest in the German Empire, and it had thousands of tools, scientific instruments, and other objects along with 288 books according to an inventory taken in 1587. Together, the libraries and the other repositories formed a system of mutually exclusive but interconnected collections for “organizing knowledge about the universe” and for demonstrating human mastery of nature.

In a work published in 1524, An die Radherrn aller stedte deutsches lands: das sie Christliche schulen auffrichten vnd hallten sollen (To the Councilmen of all Cities in Germany That They Establish and Maintain Christian Schools), Martin Luther emphasized the importance of establishing libraries for secular rulers and for the dissemination of his evangelical message. Philipp Melanchthon and Georg Spalatin, as well as the members of Lutheran parish visitation teams who attempted to reform the practices of local church communities, were also important in the establishment of libraries in the Wettin lands. However, written discussions about whether princes should establish libraries at their own courts did not take place until the second half of the sixteenth century.

In his famous advice manual, Regentenbuch (Book for Princes), the chancellor of Mansfeld, Georg Lauterbeck, made a direct connection between the establishment of a court library and the practice of ruling, stating that book collections would enhance the prestige of the ruler. He also noted that the development of printing and plentiful paper supplies had resulted in lower book prices, which made it possible for rulers to collect more volumes. Electress Anna owned a copy of Lauterbeck’s book. In addition to advancing the prestige of a ruler and underpinning church reform, a court library served the practical needs of its founder and could be used as a demonstration of wealth, as a sign of social dominance, or as an act of religious belief. Some authors saw the library as a “storehouse of knowledge” (Wissenssschatz) that could be handed down to future generations.

Book collections were also useful for pedagogical purposes: in a letter of 1568 to the court chaplain Philipp Wagner, Electress Anna ordered a catechism with “readable print” to help her four-year-old daughter Dorothea learn the alphabet and syllables. Moreover, books were visible reminders of the continuity of the Wettin dynasty. Libraries were not simply the possessions of a princely family but also part of the treasury of the entire land. Books were concrete symbols of social prestige and power like other princely collections. Catalogues of books were used to understand the extent of a library, and the inventories taken by Thumbshirn and Leonhart provided Anna and August, as well as their heirs, with this knowledge. In addition to imparting an overview of the concrete holdings of the library, catalogues also fulfilled another function in the sixteenth century: they were virtual representations of book collections. The library was therefore not only a place or a collection but also the catalogue or inventory.

Catalogues of large libraries provided information about the scope of the collection as well as the inclusion of specific texts. Above all, catalogues helped resolve the problem of systematizing and managing knowledge. It is unclear whether the elector and electress followed a specific “procurement policy” to obtain books. Leonhart’s inventory reveals that a large portion of Anna’s library consisted of new books published between 1560 and 1585. The couple examined lists of recently published works and placed orders through their representatives at the book fairs of Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig; they themselves regularly visited the fair at Leipzig. Saxon diplomats, especially Hubert Languet, made purchases for them in outlying areas.

Anna received numerous books, manuscripts, and medical recipes from acquaintances and friends, as well as chronicles and historical works from her family. The elector established a printing shop in the family castle at Dresden, where a psalter by the court chaplain Christian Schütz and other works were printed for Anna. However, the largest part of the book collection was undoubtedly ordered by court librarians such as Paul Vogel based on the recommendations of the faculties at the universities of Leipzig and Wittenberg. The places of publication listed in Leonhart’s inventory show that electoral Saxon printers were preferred by Anna and August. Although Leipzig was a center of the book trade, approximately 64 volumes in Anna’s library were printed at Wittenberg, most of which were Bibles or works written by Martin Luther and Philipp Melanchthon.

About 42 works were printed at Leipzig, 30 at Dresden, and 16 at Eisleben. Approximately 35 books were published at Frankfurt am Main, 33 at Würzburg, 31 at Uelzen, and 19 at Nuremberg. Many of the books printed at Dresden were bound by Jakob Krause (1525–85), who worked at the Saxon court from 1566 to 1585; he was “the greatest German master of the bookbinding craft and also one of the most famous European bookbinders of the time.” Little is known about Anna of Saxony’s upbringing in Denmark, but there is evidence that she was taught reading, writing, arithmetic, and religion by Tilemann von Hussen (1497–1551), who had studied with Luther and Melanchthon. Her training may have also included medicine under the guidance of Cornelius van der Hansfort, a physician at her father’s court.

Anna learned to speak, write, and read in Danish and German. There is no evidence she knew Greek or Latin. The inventory of her library shows that she owned works by the ancient authors in German translation, including Caesar’s Caij Julij Cesaris des großmechtigen ersten Roemischen Keysers Historien vom Gallier vnd der Roemer (History of the Gauls), Cicero’s Officia Ciceronis Teutsch (On Duties), Menander Protector’s Das Buch der Histori Menanders (The History of Menander), and Thucydides’s Von dem Peloponneser Krieg (The Peloponnesian War). The library also contained books to educate the young, such as the didactic poetry of Hugo von Trimberg’s Der Renner (The Runner), and Petrarch’s Von Artznei vnd Rath beydes in gutem vnd widerwertigem Glueck (Physicke Against Fortune), a collection of 254 dialogues which was enormously popular and influenced the moral thought of many Europeans during the Renaissance.

Other historical and political texts and works of advice in Anna’s library included Kaspar Hedio’s Ein Außerleßne Chronick von anfang der welt (An Excellent Chronicle from the Beginning of the World), which has an entry for 1509 about seven people brought from the New World to Rouen, possibly the earliest reference by German authors to Canadian Indians. Sebastian Münster’s Cosmographia oder beschreibung aller lander herrschaften (Cosmography) has hundreds of pages on the history and geography of Europe, as well as sections about the newly discovered territories of Africa, America, and Asia. A copy of Elector August’s Landesordnung (Territorial Ordinance) of October 1, 1555 was an important political text about administrative policing. The genre of advice books was well represented by Werner Leonard’s famous Fürstlicher Trostspiegel und christlicher Seelen-Trost (The Mirror of Princely Solace and Christian Comfort of the Soul) and Georg Lauterbeck’s Regentenbuch (Book for Princes), the most important work on political thought in German during the age of confessionalism.

According to a post-mortem estate inventory done by Thumbshirn at Annaburg, the electress kept two books on her night table: a children’s postil by M. Veit Dietrich and a religious work, Das seelige neue Jahr (The Blessed New Year). She was devoted to studying the Bible and reading other religious texts, including the apocryphal Jesus Syrach Deudsch (Book of Ecclesiasticus), a misogynist work which imparted to children the belief that women should be married and submissive to their fathers and husbands. In the sixteenth century, many Lutherans wanted to study Luther’s writings for inspiration and edification, and approximately two-thirds of Anna’s library consisted of titles by the reformer and other Lutherans. Anna purchased the nineteen-volume Wittenberg edition of Luther’s works and thus had almost all of his publications in print with the exception of the postils.

…One of Anna’s great passions was medicine. According to Thomas A. Brady, Jr., “Mother Anna,” as she was often called, not only “sewed, washed, and churned butter,” she also “bore fifteen children, and dosed the survivors and her husband when ill.” Noblewomen had long been expected to provide medical care to both the rich and poor, and throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, many of them became famous locally for their therapies. Anna had extensive contacts with other medical practitioners across the Holy Roman Empire, participating in the “pluralistic medical marketplace” available to patients in early modern Europe.

An early work in Anna’s library at Annaburg was a twenty-eight-page manuscript of gynecological recipes and advice which she began writing shortly after her marriage. Entitled Edlich guet ertzeney den Frauen (A Number of Good Medicines for Women), it describes treatments for problems associated with menstruation, pregnancy, and childbirth and provides detailed information about the measures that needed to be taken during pregnancy to avoid complications, including a section about pediatrics and post-partum care for the mother. Anna herself gave birth to fifteen children, eleven of whom died at birth or during infancy and childhood; it is not known how many miscarriages she had.

Her library also included a number of printed books about midwifery: Adam Lonitzer’s Reformation oder Ordnung für die Hebammen (Reformation or Ordinance for Midwives), Walther Hermann Ryff ’s Frauen Rosengarten (Women’s Rose Garden), and Eucharius Rößlin’s Der schwangern Frauwen und Hebammen Rosengarten (The Rose Garden of Pregnant Women and Midwives), whose works were so popular that he was called “Teacher of Europe’s Midwives.” Recipes were very popular forms of medical texts in the sixteenth century; after being written down and bound, they provided standardized procedures to practitioners and represented knowledge about the human body in textual form. Boxes and cabinets in the Annaburg library contained recipes for medicines to improve women’s health and to decrease the problems associated with pregnancy and birthing.

For example, a booklet of recipes written by Countess Dorothea of Mansfeld (1493–1578) contained information about difficult births and the methods to counteract them. In 1563, Katharina Wernerin, a widow from Zwickau, sent Anna a thirty-seven-folio booklet of recipes which included concoctions for sleeping, stomach problems, post-partum care, edema, hyperthermia, throat problems, epilepsy, shortness of breath, and chills. An ornately decorated, twenty-eight-folio manuscript of recipes sent to the electress by Hans Ungenad von Sonnegg and his wife Magdalena included a recipe for a panacea salve, as well as instructions to make a plaster for war wounds, powders to counteract rabid dog bites, and “swallow water” for kidney problems, strokes, fevers, and the removal of unseemly hair.

Other recipes aimed to prevent kidney stones, breast problems, tumors, worms, insects, fevers, low urine production, and jaundice. The Ungenads’ recipe collection was a “medical wonder and a tangible object of knowledge.” The postmortem inventory of Anna’s manuscripts on medicine lists approximately fifty handwritten volumes found on special bookshelves in the electoral library at Annaburg, and all but four of them were recipe collections. The recipe collections and manuscripts of the electress were supplemented with at least thirty-four printed books about medicine, a number exceeded only by the religious texts in her library.

…A third important part of Anna’s library consisted of works concerning agriculture. Before marrying Elector August, she learned in her homeland about an agricultural system used in Denmark and Holstein called Koppelwirtschaft, in which land was enclosed, turned into pasture, and plowed again at a later date. This procedure improved the quality of the grassland, and manure was absorbed to fertilize what would eventually be plowed again. Anna used this knowledge when she was put in charge around 1550 of an outlying farm at Ostra near Dresden by the elector, who wanted to use it to supply food to their residence in Dresden and as an experimental site for new agricultural methods.

Approximately twenty years later, the electress was named supervisor of approximately seventy of the hundred electoral demesnes in Saxony by her husband. She probably consulted her German translation of Pliny’s Natürlicher History (Natural History) to obtain information about enriching manure on the farms. Moreover, Anna possessed an important collection of classical agricultural texts by Cassianus Bassus entitled Der Veldtbaw (Farm Work), translated by Michael Herr. Anna’s library contained several manuscripts, which were eventually printed, about the administration of farms, works she probably consulted to help with her own supervisory duties. Thumbshirn’s Haushaltung in Forwergen (The Management of Outlying Farms) of 1569 deals with methods to improve planting, raising livestock and poultry, gardening, beekeeping, mills, viticulture, raising sheep, fishing, hunting, and forestry.

… Anna’s library helped make the Saxon court a “vibrant center of knowledge transactions” and a site where the “management of knowledge” was achieved. The manuscripts, printed books, and recipes signaled the electress’s education, interests, and wealth. She used personal, hands-on knowledge and expertise to gain knowledge about religion, medicine, and farming, but ownership of books and manuscripts also provided her with legitimacy and a means to search for universal truths as well. Anna was undoubtedly proud of the library, because it revealed not only her high level of literacy and social rank but also her participation in the “boom of book culture” that took place in the sixteenth century.”

- Brian J. Hale, “Anna of Saxony and Her Library.” in Early Modern Women

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Georg Spalatin, 1509, Lucas Cranach the Elder

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

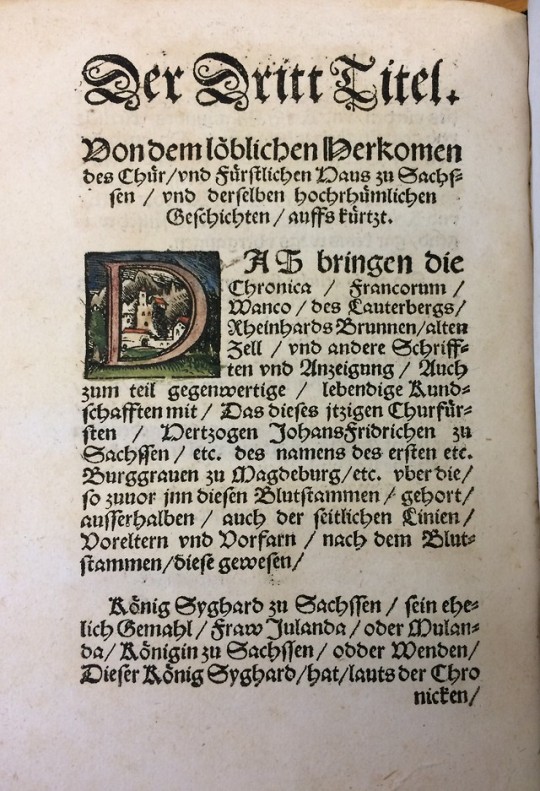

Das D

Delightful, hand-colored woodcut initial D, Decorated with a Distant, Detailed Downtown. From a 16th century history of Saxony, Germany.

Spalatin, Georg. Chronica und Herkomen der Churfürst und Fürsten : des loblichen Haus zu Sachssen... Wittenberg : G. Rhau, 1541.

172 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Georg Spalatin 1484 – 1545

was the pseudonym taken by Georg Burkhardt , an important German figure in the history of the Reformation.

0 notes

Text

IT GETS WILDER????

okay so Luther has been teasing his old buddy George Spalatin for years for not getting married—but it's, y'know, good-natured teasing among bros, because Luther himself has insisted loudly, for years, that marriage is Not For Him, right?

however. Luther abruptly changes his mind, decides to marry former nun Katharina von Bora, and when Sapaltin comes to him shortly before the wedding... y'know, in a pretty vulnerable place, given all the teasing over the years...

(emphasis mine)

Spalatin asked [Luther's] advice about a couple who wanted to delay the public eremony for a while, despite being sure of each other. It would have been obvious to Luther that Spalatin was talking about himself: The young courtier had fallen in love with a young woman but had been forced to delay marriage while he remained in the Elector's service. Luther responded by pointing out a veritable flood of quotations from Scripture, proverbs, and history all designed to prove that weddings should never be delayed, concluding: "when you're driving the piglet, you should hold the sack ready"—a rather disconcerting metaphor for marriage.

WHAT

omgggg Martin Luther cringe compilation (emphasis mine)

From 1523, groups of nuns, convinced by evangelical teachings against monasticism, had begun leaving their convents and arrived in Wittenberg, where it fell to Luther to find lodgings for them and even provide them with new clothes. He was not entirely innocent in all this. That year, Leonhard Koppe, a businessman and a relation of his friend Amsdorf, smuggled a group of nuns out of the Nimbschen convent in Duke Georg's territory and over the border to Wittenberg, hiding them among barrels of herrings. When Luther then published an open letter of congratulation to Koppe, he revealed that he had known all about the plan, which was an impudent snub to his old enemy Duke Georg. The women came from the upper nobility of his lands, but their families were unable to welcome them back for fear of offending their Catholic ruler—or so Luther argued [. . .] Luther needed to settle the women in respectable marriages as soon as possible, so as to avoid malicious gossip, and thus found himself in the unexpected position of marriage broker. As a result, the situation forced him to think about female desire. In August 1524 he wrote to some nuns, candidly informing them that, although they might no like to think so, God had created them with powerful sexual urges, which they ignored at their peril: "Though womenfolk are ashamed to admit this, nevertheless Scripture and experience show that among many thousands there is not a one whom God has given to remain in pure chastity. A woman has no control over herself." It may have been that the subject came to mind because he was beginning to be tempted himself.

#lua reads martin luther renegade and prophet#the. the piglet metaphor. i'm on the floor. luther are you ok

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Georg Spalatin, 1509, Lucas Cranach the Elder

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Georg Spalatin, 1509, Lucas Cranach the Elder

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Georg Spalatin, 1509, Lucas Cranach the Elder

https://www.wikiart.org/en/lucas-cranach-the-elder/georg-spalatin-1509

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Georg Spalatin, 1509, Lucas Cranach the Elder

https://www.wikiart.org/en/lucas-cranach-the-elder/georg-spalatin-1509

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Georg Spalatin, 1509, Lucas Cranach the Elder

https://www.wikiart.org/en/lucas-cranach-the-elder/georg-spalatin-1509

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Georg Spalatin, 1509, Lucas Cranach the Elder

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Georg Spalatin, 1509, Lucas Cranach the Elder

3 notes

·

View notes