#Fred zinneman

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"Some men think the earth is round, others think it´s flat. It is a matter of capable questions. But if it is flat, will the kings command make it round? And if it is round, will the Kings command flatten it? No. I will not sign."

A Man for All Seasons (1966).

director: Fred Zinnemann.

#a man for all seasons#filmedit#filmgifs#films#perioddramaedit#perioddramasource#perioddramagif#perioddramacentral#weloveperioddrama#periodedit#adaptationsdaily#gifshistorical#costumeedit#dailyflicks#usergina#uservintage#classicfilmsource#1960s#paul scofield#robert shaw#vanessa redgrave#fred zinneman#*#*gifs#gifs#gifset#gif#my gifs#*mygifs#*my stuff

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the surface, “A Man for All Seasons” is one of those stuffy British costume dramas from the 1960s, but I have such a soft spot for it. I first watched it when I got obsessed with the English Reformation when I was taking AP Euro. My first viewing happened to coincide with a prolonged, public saga my family was embroiled in with our Archdiocese at the time, so Thomas More being held up as an ultimate example of integrity in the Catholic Church was oddly reassuring. The irony also isn’t lost on me that the Church screwed over my family while the movie is about a man standing up for it. NB: For what it’s worth, the way the Church’s fucked over my family during this time was NOT, for a change, related to child sexual abuse.

I claimed to love the movie after my first watch. That was a huge fucking lie. There were a couple good parts but I found it stodgy and pretentious. Despite that judgment, the dialogue contained several nuggets that really resonated with me during that year from hell when we going up against the Church. It’s these jewels (as well as my since-continued fascination with the English Reformation) that motivated me watch it again and again over the next couple of years whenever it was on TCM.

In a script (and play) of absolute gems, the most famous line is probably More’s response to Rich’s perjured allegation against him: “It profits a man nothing to give his soul for the whole world. But for Wales?” That’s the line i really responded to after my first viewing. My family were being victimized by people flooding the Archdiocese with cash and the Archdiocese was doing their bidding for that money. For the Arch, my family was Wales.

However, I now find myself find myself drawn to More’s hypothetical defense of the Devil after his son-in-law suggests that every law should be cast aside to go after him. More vigorously responds (I’m leaving some stuff out here):

And when the last law was down, and the Devil turned 'round on you, where would you hide, Roper, the laws all being flat? This country is planted thick with laws…Man's laws, not God's! And if you cut them down…do you really think you could stand upright in the winds that would blow then? Yes, I'd give the Devil benefit of law, for my own safety's sake!

I was teen during those years and I was angry and wanted vengeance on the assholes who hurt my family. 15+ years later, I recognize the nuances of the entire situation; the person I initially perceived as the principal villain was just as much a victim himself (he was eventually punished with his own form of exile) while the main perpetrators, who I only learned about much later, have gone unaccountable with some going on to even greater and undeserved success. But More's defense of the Devil resonates with me because it tells us so much about the law and its purpose. Not to sound naive and like Pollyanna, if you cast it aside for even an instant, how can you trust that it won't be discarded when you truly need it. That's how it felt during that year when these people in power at the Archdiocese were discarding long-standing policy when it came to my family's situation. While they may not have been violating the law (may not- I wasn't privy to my parents' legal counsel), I can't help but laugh whenever that Archdiocese (or the Church in general) whines about legal judgment being served against them in any of the child sexual abuse cases. How can they lay down the laws and then expect them to be there for them when it's convenient. More's retort about selling your soul for so little ties in so nicely here. I didn't expect to go on and on about this. I just happened to put on the movie the in the background while I worked and wanted to say I don't think it gets the credit it deserves. However, I also understand the stuffy costume drama critiques bc they are definitely valid. I love the movie but that is still true. Paul Scofield's performance as More is such a grounded portrayal of integrity and principle. It seems like it should be impossible to embody that kind of ethic without grandstanding or pomposity but it's such a masterful turn and should be studied. Leo McKern is also fantastic and turns out such a droll, bitchy performance as an unapologetic henchman of Henry VIII. He's a delight every time he's on screen.

#a man for all seasons#paul gets pretentious on main#paul scofield#leo mckern#robert bolt#fred zinneman#wendy hiller

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Nun Story (1958) Fred Zinneman

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Documentaries are less stress"

The following one-on-one interview with Mr. Stone was conducted in Brussels. As the guest of honor during the Millenium Documentary Film Festival Brussels—which runs from March 15 until March 22—to present his documentaries “JFK Revisited: Through the Looking Glass” (2021) and “Nuclear Now” (2022), and a masterclass as well, I got to sit down with him in a Brussels hotel for a conversation on his craft that he knows inside out. With his approval, this interview didn’t focus on his two documentaries, but rather dealt with general topics and his work as a filmmaker.

Mr. Stone, after your last feature film, “Snowden” [2016], you changed your modus operandi and became a documentary filmmaker. Why did you do that?

Documentaries are different. When you make documentaries, they’re not consuming your life. You don’t have to build the sets, you don’t have to hire actors or paint walls. You don’t have to think about a hundred different things. That also means you’re no longer creating an artificial world. A documentary is something real, you have witnesses, people who went through it or who were around when it happened. So the preparation for a documentary is very different; it’s a living environment parallel to you and you’re joining it. My documentaries are a lot about political ideas and about the country, so it’s something entirely different. Making a documentary means much less work, much less money and much less stress. It’s simpler to be a documentarian.

Several of your films are based on true events, and “JFK” [1991] and “Snowden” are documentary-like features. Were they maybe your most difficult films to make?

They are difficult in the sense that you have to check everything and authenticate it. Obviously, fantasy gives you a lot more freedom: if you’re doing films like “Natural Born Killers” [1994], “U Turn” [1997] or “Savages” [2012], those are fictional. They give you more freedom, and you can f*ck around. When you’re doing “JFK” [1991], you really have to pay attention. There’s so much out there, and the film is so difficult to authenticate because it’s not like a book. The dialogue is difficult because those are real people and you don’t know what they really said. So you’re taking dramatic liberties.

When you did “Snowden,” you met Edward Snowden in unusual circumstances. What was he like?

He was very straightforward; he remindend me of a very bright boy scout. He doesn’t drink, doesn’t smoke, he doesn’t do drugs. He’s quiet, shy, polite and pleasent. He had one woman in his life at that time. He’s a serious man; I was very impressed with him and he’s not a celebrity type attention seeker. Not at all. Some people said that I made him a white knight in the movie, but they don’t know who he really is. If they knew him, they’d realize he is very sincere, very articulate, and he really believed that his oath was to the constitution—which it is—and not to the NSA or to the CIA. He was a whistleblower at twenty-nine, so I wanted to know and explore how and why he did that at such a young age.

What film or filmmaker gave you the passion to become a filmmaker?

I went to the New York Film School and the message came from Martin Scorsese who was a teacher. I had done a short film of fourteen minutes, “Last Year in Viet Nam” [1971] and he liked it. He praised it and took it to class. That didn’t happen too often; short films were mostly criticized. That was the method; it was like a Chinese commune where you showed your work to the class and everyone went bla bla bla. But this time he threw it in the class and said, ‘This is a filmmaker.’ And he said, ‘Keep it personal.’ That’s what you have to do, keep it personal. That was very good. I felt very inspired by that and then I just kept going.

So then you began making personal films, and with “Midnight Express” [1978] and “Salvador” [1986], for example—not to mention your Vietnam War trilogy—you immediately put yourself on the map with message films. That reminds me of the films Stanley Kramer or Fred Zinnemann did, for example. Is that an accurate comparison?

That’s a tough question to answer, whether they are personal or not. You don’t know how Stanley Kramer really felt. He was an emotional man with a great conscience, and you know he was passionate about nuclear war; so he did “On the Beach” [1959] with that passion. And you know he wanted to be funny when he did a comedy [“It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World,” 1963] with a lot of car crashes. He wasn’t funny, but he did make a point. “Judgement at Nuremberg” [1961] was about justice, bringing justice to the Nazis and America did the Nuremberg trials—the one good thing they did. And even then, it was compromised, but still he made the point of the Holocaust very clear. So I think we owe him because of the many films he did. They were motivated by passion. They weren’t motivated by politics, I don’t think so. It was in his heart. Of course, my interpretation of him may be different than critics who say, ‘He was just a producer.’ But I saw an early film he did with Frank Sinatra, “Not as a Stranger” [1955], and that was a very interesting film. Sinatra was great; he played the second doctor and Robert Mitchum was the first doctor who starts a relationship with a nurse who gives him the money to finish school. He uses her and then dumps her. But she comes back and plays a very good scene… But you asked a tough question. Zinnemann, I don’t relate to him the same way you do. I don’t. I knew him, I met him, but I don’t regard him in the same way. Kramer was special, although he made some stinkers too [laughs]. He also did a beautiful movie, “The Secret of Santa Vittoria” [196] with Anna Magnani, beautifully scripted, beautifully done. Anthony Quinn plays the major of this Italian town and nobody trusts him. He’s a layabout and Anna Magnani is his angry wife. That was a great movie and he should have gotten more credit for it, right?

Did it ever happen to you that you should have gotten more credit for a film you did?

Yeah. “Snowden” [2016]. I couldn’t finance it in the U.S. We moved the production to Germany because we thought we might be at risk in the United States. We had no idea what the NSA might or could do. So we financed it abroad, and that’s very disturbing: you make a film about an American and it’s not possible to finance it in the U.S.

Generally speaking, has it been easy for you to be an independent filmmaker and make most of your films without the financial support of the major studios?

I can’t rely on the studios, so I have always been independent. I bounce around with different independents. A lot of my films are owned by bankrupt corporations and sell-of assets. I work a lot with guys who get bankrupt [laughs]. I have been both ways and when I work with studios, the experience can be good. “Wall Street” [1987] was good, but the second Wall Street [“Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps,” 2010] was not because that was made by [executive] Tom Rothman. He acted like a head and would tell you what to do. It’s a whole different attitude. We give studios the power, we entitle them—every filmmaker in some way has a relationship with the studios so he’s always thinking about them because he’s gotta deliver his film and they have the money. Sometimes you’re the slave of that money, and sometimes… f*ck ’em [laughs]. Some filmmakers are always fighting against the studios; it’s a tedious relationship because it’s a slave relationship. Unless you prefer independent. But then, of course, you have to go to them for distribution.

Alain Parker once told me he always wanted a production deal and at the same time a distribution deal, otherwise you have to go shopping with your film. Did you ever have to do that?

Of course. A lot. With “Nuclear Now” we were invited to Cannes where you can get a lot of publicity, but they wanted to hold the film for America in October, and by that time it was not noticed. But it’s okay; that’s the business and I get tired of promotion anyway. Besides, documentaries don’t need that. You just throw them out there and f*ck ’em. You know what I mean; you have to be a showman and you have to care. A showman cares about the results. To go through that again, watching box office, counting numbers,… all that stuff is pretty tiring.

Have you always been able to cast the actors that you wanted?

No, but I had pretty much freedom. I mean, it’s always a deal pressure kind of thing. They mention a few names and things happen. There are a lot of cooks in the kitchen, but somehow you have to be the master cook [laughs].

Does that mean you have to compromise?

Always. But you don’t have to say yes. I never say yes to an actor overnight. I have never done that. I have made mistakes, but I have never said yes to an actor right away.

When you write a screenplay, do you have certain actors in mind?

Yes, but that’s more elusive because by the time you go through the casting process, you have seen different interpretations and you may prefer an actor’s interpretation to your own. I had many actors reading for me—that helps—or I have them read on tape with a casting director and then I see the tape. You don’t have to be there always. Sometimes if you’re in the room, you’re the gorilla, you know.

In your films you always have a great cast of supporting actors, such as Sylvia Miles, Millie Perkins, Haing S. Ngor, Paul Sovino, E.G. Marshall, Eli Wallach, Madeline Kahn… Mel Brooks recently said that ‘Madeline Kahn was maybe the single best comedian that ever lived.’

Casting your supporting actors is always very special. Most of what you’re doing is picking supporting actors. The main actors line up on money deals; it’s a money situation with agents and lawyers. Whereas the supporting actors, that’s a different story, that’s really where the casting process kicks in.

How closely do you collaborate with your casting directors?

A lot because he or she will make suggestions and knows who is out there working or not. You don’t know and you can’t remember everything. Sometimes you have a thought in mind, like, ‘I want a Cary Grant type for this.’

You have a long and rewarding career as a filmmaker, with a string of highlights. Is there a secret, or is it always a challenge?

Well, it’s been okay. Is it a challenge? I would say yes. It’s a challenge to stay relevant, it’s a challenge to be interested in society but that naturally comes to me. My ideas may not be popular at the moment, but they are fresh—at least, to me, they are. I don’t talk like most directors, and I can’t stand most directors’ irresponsibility about political situations. Most directors want to be friends with everybody and avoid all controversy. But that’s not the way you should speak. You should speak your mind. But then you risk ostracism.

Did you ever have any problems with your actors?

Yeah sure. Some got drunk, some were uncommunicative and stubborn, some dropped out. Bill Paxton, for example, dropped out of “U Turn” [1997] and was replaced by Sean Penn because he didn’t understand his character.

How important are your three Oscars to you?

They look good in the corner. Memories. I think I’ve passed the level of merit. I see myself as a better filmmaker, although others may not agree. But the Oscars, it’s a game, you know. Oscar chasing is like high school politics where they want to be president of the class. I don’t like any of that.

You worked with a lot of great actors and big stars. Have you ever been starstruck?

Yes. When I was forty, I won an Oscar for [directing] “Platoon” [1986]. Liz Taylor presented me the Oscar on stage and then she kissed me. She was my sweetheart, my dream girl, during the 1950s and 1960s, so that was a special moment for me.

-Q&A at the Millenium Documentary Film Festival Brussels, March 15, 2024

0 notes

Text

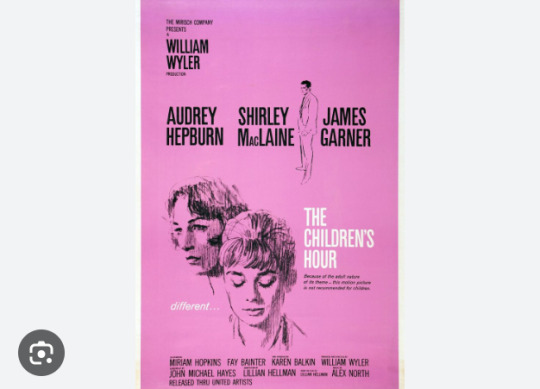

Vijftig jaar geleden: première van "The children's hour"

Op 19 december 1961 ging “The children’s hour” van William Wyler in première. De film werd uitgebracht als The Loudest Whisper in het Verenigd Koninkrijk. Continue reading Untitled

View On WordPress

#Audrey Hepburn#dashiell hammett#Fay Bainter#Fred Zinneman#James Garner#Jane Fonda#Joe McCarthy#Karen Balkin#Lilian Hellman#Merle Oberon#Miriam Hopkins#Myrna Loy#Shirley MacLaine#Vanessa Redgrave#William Powell#William Wyler

1 note

·

View note

Text

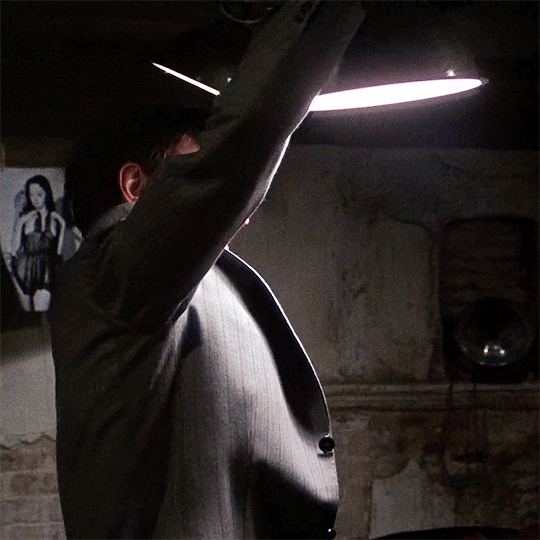

Ronald Pickup as The Forger in THE DAY OF THE JACKAL (1973), dir. Fred Zinneman

Forget about makeup. The most important thing is the skin—your skin must look grey and tired. We used the trick in the army to fake illness and get out of fatigue duty. Can you get hold of some cordite?

#the day of the jackal#film#filmedit#film gifs#70s film#moviegifs#moviedit#ronald pickup#edward fox#fred zinnemann#character edit#my graphics#I love DotJ in every respect - all the performances are perfect - but I love how different this performance is to the others#it's a very quiet measured tense film#and pickup's performance is far livelier and more expressive than the rest#the character is fun! evidently not a decent person by any stretch but slightly likeable nevertheless#the difference broadens the story#I keep hoping I'll see him in a role/film I enjoy as much as this

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The largest trove of personal Grace Kelly letters to come to market

An extensive and important archive of letters, ephemera and correspondence between Grace Kelly and her friend and personal secretary Prudence Wise. [Various places including Hollywood, New York, Cannes, Monaco, and elsewhere: 1949-1968]. A large archive including autograph and typed letters signed, various notes, postcards, photographs of Grace, Prince Rainier and their children (both official and personal), telegrams, royal invitations, and other ephemera all relating to the life of Grace Kelly and her relationship with Prudence "Prudy" Wise. Kelly generally does not date her letters but the postmarked envelopes provide a chronology. Some handling wear, usual folds, wear to envelopes, very well preserved overall and the letters individually sleeved.

Prudence "Prudy" Wise Kudner was raised in Jacksonville, Florida and attended Duke before moving to New York City and becoming roommates with Grace Kelly, Sally Parrish, and Carolyn Scott at the Barbizon Hotel for Women. The earliest items in this extensive archive include a photograph of Grace with two of the women, a phone message note on Barbizon stationery, and a note from Grace to Prudy in Jacksonville mentioning both Sally and Carolyn. The first substantial letter is postmarked April 1949, months before her Broadway debut that November, and is eight pages in pencil on a delicate stationery. The letter regales Prudy with the long tale of a dinner introducing a suitor named Don [Richardson] to Grace's parents which went disastrously resulting in the end of their relationship and an argument with her parents, but on the bright side Kelly makes note of the positive theater connections made through Don. Following some successful modeling work and her performance on Broadway in Strindberg's The Father, Grace had her first film role in Twentieth Century Fox's 1951 Fourteen Hours. In early 1952, Kelly answers questions for Prudy regarding her newest suitor Gene [Lyons] and mentions in a postcard that follows seeing a screening of Fred Zinneman's High Noon, her first major film role. High Noon was followed by the filming in Nairobi of John Ford's Mogambo, a role offered to Kelly after Gene Tierney was forced to drop out due to health issues, and two letters are written from Africa, one on fantastic Mogambo stationery. Kelly mentions "after leaving camp two weeks ago, Frank [Sinatra], Ava [Gardner], and Clark [Gable] & I went to Malindi on the coast for 5 wonderful days... there was a terrible champagne binge for about ten days over Christmas ... we all went on the wagon until Rome. Ava and I are now great pals..." before reporting that illness, injuries and deaths had plagued the production and "the old man [Sinatra] is very anxious to leave Africa." Into 1953, Kelly is at the Savoy Hotel in London while Mogambo is edited, she here reports that "Gable and Sam Zimbalist are cutting the picture to pieces which breaks my heart - I'm not speaking to Clark these days and neither is Ava - but don't tell anyone that." For her performance in Mogambo, Kelly won a Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actress and was nominated for her first Academy Award.

In the few years from mid-1953 through her marriage to Prince Rainier in 1956, Grace Kelly starred in some of the best and most stylish films of the period and became a bonafide movie star. The archive is rich in long letters from this period, including several on the stationery of the legendary Chateau Marmont in Hollywood starting in July 1953. It is here that Kelly first mentions that she "met Hitchcock" at the time she was filming Dial M for Murder, the first film in their important collaboration. In the first letter, Kelly mentions her arm is sore from playing tennis - her character is the wife of a professional player - and that "Tomorrow I test my wardrobe and see how it will all turn out in 3D," the medium for which the film was intended although most theaters showed the film in 2D. She also notes in the next letter that "They are still debating the colour of my hair. It comes out bright red in Warnercolour and Hitchcock is having a fit." In the next letter, Kelly reports "Sat. night I had dinner with the Hitchcocks. We went to Perino's which was lovely... there are really so few nice places to have dinner here - most of them are flashy eating joints." She closes noting how on the one-year anniversary of the Grace Kelly fan club she took time to speak all 15 girls who attended a party and called her on the phone.

Early the next year, Kelly is preparing to move into her new apartment in New York in the Manhattan House but tells Prudy she is first moving to the Hotel Bel-Air in Los Angeles. One short letter is written on Paramount Pictures stationery, possibly during the filming of The Country Girl as in the next letter on Hotel Bel Air stationery Kelly mentions seeing a screening of the film and having spent a day swimming in the pool of the famous costume designer Edith Head. It is in this letter that Grace Kelly first mentions a new suitor, Oleg Cassini, and describes how he procured the typewriter she uses ("the only one in Beverly Hills") and their spectacular outings together, writing "last Saturday we went to a big part at Jack Warners... and the weekend before we went up to Hitch's ranch in Santa Cruz... We had dinner with Bing one night... My father isn't very happy over the prospect of Oleg as a son-in-law ... but the plan now is to be married the first part of October..." This excellent letter closes with a manuscript mention of tickets for Rear Window. 1954 was the most significant year thus far in Grace Kelly's career, having won the Best Actress Oscar for The Country Girl and starred in two Hitchcock features: Dial M for Murder and Rear Window.

We catch up with Grace in early April 1956, just days before her royal wedding to Prince Rainier of Monaco who she had met in May 1955. Kelly tells Prudy "it is alright with me if you want to write an account of the wedding as long as it is not on the spot reporting and written afterwards as I am not supposed to have any press on my list of invitations." From the period of the wedding are invitations and printed materials, picture postcards, and envelopes with stamps bearing images of the new couple, all vestiges of Grace's new life as the Princess of Monaco. Many of Grace's letters from here on are written on royal stationery. In August 1956, Kelly asks Prudy "Can you believe that I am pregnant?" and mentions buying maternity clothes in Paris before heading to the U.S. About a week before the arrival of Princess Caroline in January 1957, Kelly expresses anxiety that "I still can't get used to being a wife let alone a mother... it has been so long since I led a normal life that I imagine it will take a while to become completely domesticated..." A very fine item is a picture postcard depicting Prince Rainier standing in uniform next to a gowned Princess Grace holding baby Caroline. In early 1958, Prince Albert was born and Grace glowingly reports "Our little boy is really too sweet for words. He is gaining weight rapidly and will soon be a big fatty. Caroline loves him but gets very upset when he cries. It is really wonderful having two such beautiful babies and one of each!" Grace has included several pictures of her with the children in these letters. Later that year, Grace is stateside and describes a trip to California to meet with Metro Pictures, a trip to Jamaica with Colliers, and her and Rainier's new apartment on Fifth Ave which she will decorate with a "clock from one of the To Catch a Thief sets" gifted to her by Cary Grant.

While the final years of the correspondence is voluminous, most topics include Grace's travels and instructions for when Prudy visits her, news of her children, and her efforts with orphans, the Red Cross, and other organizations. This group of letters offers insight to Grace's day-to-day in a relatively private time in her very public life. In 1958, Prudy married (with Grace as her matron of honor) and settled on a farm in Maryland where the letters continued to reach her from Monaco, Switzerland, Spain and elsewhere. The correspondence in this archive concludes in 1968, this being about the time Prudy began to suffer the leukemia that ended her life at just 42 in 1973. Grace Kelly died in 1982 at just 52 years old from injuries sustained when a cerebral hemmorhrage caused an automobile accident.

This is a remarkable archive that we believe to be unpublished and unknown to biographers. Grace Kelly's rise from her first days as an actress in New York to becoming the Princess of Monaco is a real-life fairy tale. Worthy of collector, institutional, and scholarly interest, we trace no other archive that tracks the career and personal life of Grace Kelly in her own words in such depth.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Great Depression: A Sign of the Times,” 1932. A man carries a sign reading, “I demand my life savings $2950 from the Bankers Trust Co. 14 Wall St. NY.” Photo: Fred Zinneman via Bridgeman Images

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Great Depression: A Sign of the Times,” 1932. A man carries a sign reading, “I demand my life savings $2950 from the Bankers Trust Co. 14 Wall St. NY.” Photo: Fred Zinneman via Bridgeman Images

😥

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

High Noon (1952), Fred Zinneman

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Le donne sanno quando entrano in menopausa, gli uomini no,

lo capiscono col tempo.”

·92 anni fa nasceva OMAR SHARIF, (Alessandria, Egitto, 10 aprile 1932 - Il Cairo, Egitto, 10 luglio 2015).

L'attore nato ad Alessandia (ma giramondo per vocazione) incarna quella che nell'immaginario collettivo è la vita di un uomo ricco, bello, famoso, adorato dalle masse e conteso dalle donne più affascinanti del pianeta. Un mito alimentato dall'indolente Sharif, che negli anni '60, all'apice della carriera dichiarava ai giornalisti «Lavoro perché mi piace il lusso e quando finisco i soldi, sono costretto a tornare a recitare».

Seppure per necessità, ha lavorato con i più grandi registi - Fred Zinneman (...e venne il giorno della vendetta), Anthony Mann (La caduta dell'impero romano), William Wyler (Funny Girl), Sidney Lumet (La virtù sdraiata) - ed è stato l'incarnazione della bellezza esotica, della fierezza, del coraggio e del romanticismo nei due film che gli hanno regalato la consacrazione, entrambi di David Lean: Lawrence d'Arabia (un Golden Globe e una nomination all'Oscar) e Il Dottor Zivago (nomination al Golden Globe).

Al cinema era arrivato grazie alla madre, che lo mandò in un college inglese, dove Omar dimagrì («da ragazzo ero veramente grasso») e imparò la lingua, e a Youssef Chahine, che lo fece debuttare nel '53. Divo del cinema egiziano fin da subito, è poi diventato una star internazionale, con una propensione ai ruoli storici (è stato Che Guevara in Che!, Genghis Khan nell'omonimo film, l'arciduca Rodolfo in Mayerling, il principe Feodor in Pietro il Grande), romantici (Il seme del tamarindo, C'era una volta, Funny Girl) e d'avventura (L'ultima valle, Ghiaccio verde, Le meravigliose avventure di Marco Polo, Ashanti).

Nel 2003, Omar Sharif è tornato sulle scene, dopo un periodo di silenzio (aveva interpretato Il tredicesimo guerriero, decidendo di «non recitare più in simili sciocchezze»), con un ruolo importante, quello del negoziante arabo che fa amicizia con un bambino ebreo in Monsieur Ibrahim e i fiori del Corano. Una scelta forte, con cui lanciare un messaggio di pace tra ebrei e arabi in un momento storico-politico nerissimo, gratificata con un doppio riconoscimento al festival di Venezia: il premio del pubblico e il Leone d'oro alla carriera.

Sharif muore nel luglio del 2015 in un ospedale del Cairo, in Egitto, dove era stato ricoverato per un attacco di cuore. Aveva 83 anni.

ARACELI CINEMAdiCITTA'

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Turner Classic Movies Fan Site ·

Ernest Borgnine: "I went to work the first day and as luck would have it, my first scene was with Frank Sinatra and I'm dying inside, because here was the man who sang 'Nancy' (I named my daughter because of that song). My idol, my everything. I loved him in everything he ever did. And I said, 'How can I, a mere nothing, come on here?'... but I knew I had to play this part as the meanest s.o.b. that ever existed, otherwise the part won't play. So I was out there pounding the piano and everything else, and we started this scene. I'm looking around and I see Frank Sinatra dancing with this girl. And I see Montgomery Clift over with somebody else. And over standing on the side were Deborah Kerr and Burt Lancaster talking to Fred Zinnemans. I was just engulfed with stars. And I'm just shaking, you know. And Fred suddenly looked up and said, 'Okay, begin the scene!' So we started. I'm playing the piano and it came to the point where Frank says, 'Come on, why don't you stop this banging on the piano, will ya? Give us a chance with our music.' And I stood up to say my first line. I said, 'Listen, you little wop.' He looked up at me, and as he looked up at me, he broke out into a smile and he said, 'My God, he's ten feet tall!' Do you know, the whole thing just collapsed. His laughter broke the tension. It was so marvelous. I've never forgotten Frank for that. He was the most wonderful guy to work with that you ever saw in your life. He knew how I must have felt, you know. And because of it, he took the time to break that tension. That's something that I have done with everybody that I've ever worked with since. I break the ice for the other people. And I think it's nice, because it reverberated all down the line."

Photo: Ernest Borgnine and Frank Sinatra in From Here to Eternity, 1953.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Polska tajemnica legendarnego Freda Zinnemanna. "Nie powiedział przy mnie nawet jednego słowa po polsku"

Fred Zinneman i Audrey Hepburn na planie “Historii zakonnicy” Zdobył cztery Oscary, aż dziesięć razy był nominowany do nagrody Akademii. Fred Zinnemann urodził się w Rzeszowie, ale przez całe życie utrzymywał, że w Wiedniu. Swoje polskie korzenie odkrył Tim Zinnemann, jedyny syn reżysera. W rodzinnym mieście odsłonił nawet tablicę upamiętniającą ojca. Być może jako dziecko oglądał w Rzeszowie,…

0 notes

Text

The largest trove of personal Grace Kelly letters to come to market

Estate / Collection: From a Las Vegas Collection. Sold for + 126K dollars.

Prudence "Prudy" Wise Kudner was raised in Jacksonville, Florida and attended Duke before moving to New York City and becoming roommates with Grace Kelly, Sally Parrish, and Carolyn Scott at the Barbizon Hotel for Women. The earliest items in this extensive archive include a photograph of Grace with two of the women, a phone message note on Barbizon stationery, and a note from Grace to Prudy in Jacksonville mentioning both Sally and Carolyn. The first substantial letter is postmarked April 1949, months before her Broadway debut that November, and is eight pages in pencil on a delicate stationery. The letter regales Prudy with the long tale of a dinner introducing a suitor named Don [Richardson] to Grace's parents which went disastrously resulting in the end of their relationship and an argument with her parents, but on the bright side Kelly makes note of the positive theater connections made through Don. Following some successful modeling work and her performance on Broadway in Strindberg's The Father, Grace had her first film role in Twentieth Century Fox's 1951 Fourteen Hours. In early 1952, Kelly answers questions for Prudy regarding her newest suitor Gene [Lyons] and mentions in a postcard that follows seeing a screening of Fred Zinneman's High Noon, her first major film role. High Noon was followed by the filming in Nairobi of John Ford's Mogambo, a role offered to Kelly after Gene Tierney was forced to drop out due to health issues, and two letters are written from Africa, one on fantastic Mogambo stationery. Kelly mentions "after leaving camp two weeks ago, Frank [Sinatra], Ava [Gardner], and Clark [Gable] & I went to Malindi on the coast for 5 wonderful days... there was a terrible champagne binge for about ten days over Christmas ... we all went on the wagon until Rome. Ava and I are now great pals..." before reporting that illness, injuries and deaths had plagued the production and "the old man [Sinatra] is very anxious to leave Africa." Into 1953, Kelly is at the Savoy Hotel in London while Mogambo is edited, she here reports that "Gable and Sam Zimbalist are cutting the picture to pieces which breaks my heart - I'm not speaking to Clark these days and neither is Ava - but don't tell anyone that." For her performance in Mogambo, Kelly won a Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actress and was nominated for her first Academy Award.

In the few years from mid-1953 through her marriage to Prince Rainier in 1956, Grace Kelly starred in some of the best and most stylish films of the period and became a bonafide movie star. The archive is rich in long letters from this period, including several on the stationery of the legendary Chateau Marmont in Hollywood starting in July 1953. It is here that Kelly first mentions that she "met Hitchcock" at the time she was filming Dial M for Murder, the first film in their important collaboration. In the first letter, Kelly mentions her arm is sore from playing tennis - her character is the wife of a professional player - and that "Tomorrow I test my wardrobe and see how it will all turn out in 3D," the medium for which the film was intended although most theaters showed the film in 2D. She also notes in the next letter that "They are still debating the colour of my hair. It comes out bright red in Watener colour and Hitchcock is having a fit." In the next letter, Kelly reports "Sat. night I had dinner with the Hitchcocks. We went to Perino's which was lovely... there are really so few nice places to have dinner here - most of them are flashy eating joints." She closes by noting how on the first anniversary of the Grace Kelly fan club she took time to speak to all 15 girls who attended a party and called her on the phone.

Early the next year, Kelly is preparing to move into her new apartment in New York in the Manhattan House but tells Prudy she is first moving to the Hotel Bel-Air in Los Angeles. One short letter is written on Paramount Pictures stationery, possibly during the filming of The Country Girl as in the next letter on Hotel Bel Air stationery Kelly mentions seeing a screening of the film and having spent a day swimming in the pool of the famous costume designer Edith Head. It is in this letter that Grace Kelly first mentions a new suitor, Oleg Cassini, and describes how he procured the typewriter she uses ("the only one in Beverly Hills") and their spectacular outings together, writing "last Saturday we went to a big part at Jack Warners... and the weekend before we went up to Hitch's ranch in Santa Cruz... We had dinner with Bing one night... My father isn't very happy over the prospect of Oleg as a son-in-law ... but the plan now is to be married the first part of October..." This excellent letter closes with a manuscript mention of tickets for Rear Window. 1954 was the most significant year thus far in Grace Kelly's career, having won the Best Actress Oscar for The Country Girl and starred in two Hitchcock features: Dial M for Murder and Rear Window.

We catch up with Grace in early April 1956, just days before her royal wedding to Prince Rainier of Monaco who she had met in May 1955. Kelly tells Prudy "it is alright with me if you want to write an account of the wedding as long as it is not on the spot reporting and written afterwards as I am not supposed to have any press on my list of invitations." From the period of the wedding are invitations and printed materials, picture postcards, and envelopes with stamps bearing images of the new couple, all vestiges of Grace's new life as the Princess of Monaco. Many of Grace's letters from here on are written on royal stationery. In August 1956, Kelly asks Prudy "Can you believe that I am pregnant?" and mentions buying maternity clothes in Paris before heading to the U.S. About a week before the arrival of Princess Caroline in January 1957, Kelly expresses anxiety that "I still can't get used to being a wife let alone a mother... it has been so long since I led a normal life that I imagine it will take a while to become completely domesticated..." A very fine item is a picture postcard depicting Prince Rainier standing in uniform next to a gowned Princess Grace holding baby Caroline. In early 1958, Prince Albert was born and Grace glowingly reports "Our little boy is really too sweet for words. He is gaining weight rapidly and will soon be a big fatty. Caroline loves him but gets very upset when he cries. It is really wonderful having two such beautiful babies and one of each!" Grace has included several pictures of her with the children in these letters. Later that year, Grace is stateside and describes a trip to California to meet with Metro Pictures, a trip to Jamaica with Colliers, and her and Rainier's new apartment on Fifth Ave which she will decorate with a "clock from one of the To Catch a Thief sets" gifted to her by Cary Grant.

While the final years of the correspondence is voluminous, most topics include Grace's travels and instructions for when Prudy visits her, news of her children, and her efforts with orphans, the Red Cross, and other organizations. This group of letters offers insight to Grace's day-to-day in a relatively private time in her very public life. In 1958, Prudy married (with Grace as her matron of honor) and settled on a farm in Maryland where the letters continued to reach her from Monaco, Switzerland, Spain and elsewhere. The correspondence in this archive concludes in 1968, this being about the time Prudy began to suffer the leukemia that ended her life at just 42 in 1973. Grace Kelly died in 1982 at just 52 years old from injuries sustained when a cerebral hemmorhrage caused an automobile accident.

This is a remarkable archive that we believe to be unpublished and unknown to biographers. Grace Kelly's rise from her first days as an actress in New York to becoming the Princess of Monaco is a real-life fairy tale. Worthy of collector, institutional, and scholarly interest, we trace no other archive that tracks the career and personal life of Grace Kelly in her own words in such depth

-DOYLE AUCTIONS.

0 notes

Text

“Making a documentary means much less work, much less money, much less stress”

Oliver Stone (b. 1946) is a legendary American film director, producer, screenwriter and author. He’s known and praised for his ‘dramas about individuals in personal struggles,’ as he describes his films on his website, and considers himself a ‘dramatist rather than a political filmmaker.’

During the past fifty years—give or take a few years—the outspoken, rabble-rousing, highly acclaimed and three-time Academy Award winning film director tackled various subjects. He directed a trilogy on the Vietnam War (“Platoon,” 1986; “Born on the Fourth of July,” 1989; “Heaven & Earth,” 1993) and did three films about U.S. Presidents (“JFK,” 1991; “Nixon,” 1995; “W.,” 2008—on George W. Bush while he was still in office). He also made crime dramas and, in recent years, a series of solid and, to some, controversial documentary features. For the first one, on Fidel Castro, entitled “Comandante” (2003), he went to Cuba.

His latest documentairy features include “The Putin Interviews” (2017), a four-part, four-hour television series with interviews conducted with Putin between 2015-2017, “JFK Revisited: Through the Looking Glass” (2021) with newly declassified information about JFK’s assassination, and his latest documentary, “Nuclear Now” (2022), stating that nuclear energy is the best solution to combat the climate change crisis.

Mr. Stone, a Vietnam War veteran who distinguished himself in combat and earned two Purple Hearts and a Bronze Star, first broke into Hollywood as a screenwriter with his Oscar-winning screenplay for Alan Parker’s prison drama “Midnight Express” (1978), based on the 1977 memoir of Billy Hayes. The film established him as a dynamic stylist and tough-minded writer who pulled no punches. A few years later, he brought the same intensity to his screenplay for Brian De Palma’s remake of “Scarface” (1983) and his career-changing directorial debut films “Salvador” and “Platoon” (both 1986)—the latter earning him an Academy Award for Best Director. Although working mostly independently, “Wall Street” (1987), which earned Michael Douglas an Academy Award as Best Actor, became his first and one of his few big-budget films.

Throughout his career, Mr. Stone remained one of the most accomplished raconteurs and politically-charged directors of his generation. He made several exceptional and compelling films that cemented his place as one of Hollywood’s most versatile film directors.

He also authored a semi-autobiographical novel “A Child Night’s Dream” (1997), his captivating memoir “Chasing the Light: Writing, Directing, and Surviving ‘Platoon,’ ‘Midnight Express,’ ‘Scarface,’ ‘Salvador,’ and the Movie Game” (2020), and “JFK Revisited: Through the Looking Glass” (2022, based on the documentary; written by James DiEugenio, with an introduction by Mr. Stone).

The following one-on-one interview with Mr. Stone was conducted in Brussels. As the guest of honor during the Millenium Documentary Film Festival Brussels—which runs from March 15 until March 22—to present his documentaries “JFK Revisited: Through the Looking Glass” (2021) and “Nuclear Now” (2022), and a masterclass as well, I got to sit down with him in a Brussels hotel for a conversation on his craft that he knows inside out. With his approval, this interview didn’t focus on his two documentaries, but rather dealt with general topics and his work as a filmmaker.

Mr. Stone, after your last feature film, “Snowden” [2016], you changed your modus operandi and became a documentary filmmaker. Why did you do that?

Documentaries are different. When you make documentaries, they’re not consuming your life. You don’t have to build the sets, you don’t have to hire actors or paint walls. You don’t have to think about a hundred different things. That also means you’re no longer ceating an artificial world. A documentary is something real, you have witnesses, people who went through it or who were around when it happened. So the preparation for a documentary is very different; it’s a living environment parallel to you and you’re joining it. My documentaries are a lot about political ideas and about the country, so it’s something entirely different. Making a documentary means much less work, much less money and much less stress. It’s simpler to be a documentarian.

Several of your films are based on true events, and “JFK” [1991] and “Snowden” are documentary-like features. Were they maybe your most difficult films to make?

They are difficult in the sense that you have to check everything and authenticate it. Obviously, fantasy gives you a lot more freedom: if you’re doing films like “Natural Born Killers” [1994], “U Turn” [1997] or “Savages” [2012], those are fictional. They give you more freedom, and you can f*ck around. When you’re doing “JFK” [1991], you really have to pay attention. There’s so much out there, and the film is so difficult to authenticate because it’s not like a book. The dialogue is difficult because those are real people and you don’t know what they really said. So you’re taking dramatic liberties.

When you did “Snowden,” you met Edward Snowden in unusual circumstances. What was he like?

He was very straightforward; he remindend me of a very bright boy scout. He doesn’t drink, doesn’t smoke, he doesn’t do drugs. He’s quiet, shy, polite and pleasent. He had one woman in his life at that time. He’s a serious man; I was very impressed with him and he’s not a celebrity type attention seeker. Not at all. Some people said that I made him a white knight in the movie, but they don’t know who he really is. If they knew him, they’d realize he is very sincere, very articulate, and he really believed that his oath was to the constitution—which it is—and not to the NSA or to the CIA. He was a whistleblower at twenty-nine, so I wanted to know and explore how and why he did that at such a young age.

What film or filmmaker gave you the passion to become a filmmaker?

I went to the New York Film School and the message came from Martin Scorsese who was a teacher. I had done a short film of fourteen minutes, “Last Year in Viet Nam” [1971] and he liked it. He praised it and took it to class. That didn’t happen too often; short films were mostly criticized. That was the method; it was like a Chinese commune where you showed your work to the class and everyone went bla bla bla. But this time he threw it in the class and said, ‘This is a filmmaker.’ And he said, ‘Keep it personal.’ That’s what you have to do, keep it personal. That was very good. I felt very inspired by that and then I just kept going.

So then you began making personal films, and with “Midnight Express” [1978] and “Salvador” [1986], for example—not to mention your Vietnam War trilogy—you immediately put yourself on the map with message films. That reminds me of the films Stanley Kramer or Fred Zinnemann did, for example. Is that an accurate comparison?

That’s a tough question to answer, whether they are personal or not. You don’t know how Stanley Kramer really felt. He was an emotional man with a great conscience, and you know he was passionate about nuclear war; so he did “On the Beach” [1959] with that passion. And you know he wanted to be funny when he did a comedy [“It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World,” 1963] with a lot of car crashes. He wasn’t funny, but he did make a point. “Judgement at Nuremberg” [1961] was about justice, bringing justice to the Nazis and America did the Nuremberg trials—the one good thing they did. And even then, it was compromised, but still he made the point of the Holocaust very clear. So I think we owe him because of the many films he did. They were motivated by passion. They weren’t motivated by politics, I don’t think so. It was in his heart. Of course, my interpretation of him may be different than critics who say, ‘He was just a producer.’ But I saw an early film he did with Frank Sinatra, “Not as a Stranger” [1955], and that was a very interesting film. Sinatra was great; he played the second doctor and Robert Mitchum was the first doctor who starts a relationship with a nurse who gives him the money to finish school. He uses her and then dumps her. But she comes back and plays a very good scene…

But you asked a tough question. Zinnemann, I don’t relate to him the same way you do. I don’t. I knew him, I met him, but I don’t regard him in the same way. Kramer was special, although he made some stinkers too [laughs]. He also did a beautiful movie, “The Secret of Santa Vittoria” [196] with Anna Magnani, beautifully scripted, beautifully done. Anthony Quinn plays the major of this Italian town and nobody trusts him. He’s a layabout and Anna Magnani is his angry wife. That was a great movie and he should have gotten more credit for it, right?

Did it ever happen to you that you should have gotten more credit for a film you did?

Yeah. “Snowden” [2016]. I couldn’t finance it in the U.S. We moved the production to Germany because we thought we might be at risk in the United States. We had no idea what the NSA might or could do. So we financed it abroad, and that’s very disturbing: you make a film about an American and it’s not possible to finance it in the U.S.

Generally speaking, has it been easy for you to be an independent filmmaker and make most of your films without the financial support of the major studios?

I can’t rely on the studios, so I have always been independent. I bounce around with different independents. A lot of my films are owned by bankrupt corporations and sell-of assets. I work a lot with guys who get bankrupt [laughs]. I have been both ways and when I work with studios, the experience can be good. “Wall Street” [1987] was good, but the second Wall Street [“Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps,” 2010] was not because that was made by [executive] Tom Rothman. He acted like a head and would tell you what to do. It’s a whole different attitude. We give studios the power, we entitle them—every filmmaker in some way has a relationship with the studios so he’s always thinking about them because he’s gotta deliver his film and they have the money. Sometimes you’re the slave of that money, and sometimes… f*ck ’em [laughs]. Some filmmakers are always fighting against the studios; it’s a tedious relationship because it’s a slave relationship. Unless you prefer independent. But then, of course, you have to go to them for distribution.

Alain Parker once told me he always wanted a production deal and at the same time a distribution deal, otherwise you have to go shopping with your film. Did you ever have to do that?

Of course. A lot. With “Nuclear Now” we were invited to Cannes where you can get a lot of publicity, but they wanted to hold the film for America in October, and by that time it was not noticed. But it’s okay; that’s the business and I get tired of promotion anyway. Besides, documentaries don’t need that. You just throw them out there and f*ck ’em. You know what I mean; you have to be a showman and you have to care. A showman cares about the results. To go through that again, watching box office, counting numbers,… all that stuff is pretty tiring.

Have you always been able to cast the actors that you wanted?

No, but I had pretty much freedom. I mean, it’s always a deal pressure kind of thing. They mention a few names and things happen. There are a lot of cooks in the kitchen, but somehow you have to be the master cook [laughs].

Does that mean you have to compromise?

Always. But you don’t have to say yes. I never say yes to an actor overnight. I have never done that. I have made mistakes, but I have never said yes to an actor right away.

When you write a screenplay, do you have certain actors in mind?

Yes, but that’s more elusive because by the time you go through the casting process, you have seen different interpretations and you may prefer an actor’s interpretation to your own. I had many actors reading for me—that helps—or I have them read on tape with a casting director and then I see the tape. You don’t have to be there always. Sometimes if you’re in the room, you’re the gorilla, you know.

In your films you always have a great cast of supporting actors, such as Sylvia Miles, Millie Perkins, Haing S. Ngor, Paul Sovino, E.G. Marshall, Eli Wallach, Madeline Kahn… Mel Brooks recently said that ‘Madeline Kahn was maybe the single best comedian that ever lived.’

Casting your supporting actors is always very special. Most of what you’re doing is picking supporting actors. The main actors line up on money deals; it’s a money situation with agents and lawyers. Whereas the supporting actors, that’s a different story, that’s really where the casting process kicks in.

How closely do you collaborate with your casting directors?

A lot because he or she will make suggestions and knows who is out there working or not. You don’t know and you can’t remember everything. Sometimes you have a thought in mind, like, ‘I want a Cary Grant type for this.’

You have a long and rewarding career as a filmmaker, with a string of highlights. Is there a secret, or is it always a challenge?

Well, it’s been okay. Is it a challenge? I would say yes. It’s a challenge to stay relevant, it’s a challenge to be interested in society but that naturally comes to me. My ideas may not be popular at the moment, but they are fresh—at least, to me, they are. I don’t talk like most directors, and I can’t stand most directors’ irresponsibility about political situations. Most directors want to be friends with everybody and avoid all controversy. But that’s not the way you should speak. You should speak your mind. But then you risk ostracism.

Did you ever have any problems with your actors?

Yeah sure. Some got drunk, some were uncommunicative and stubborn, some dropped out. Bill Paxton, for example, dropped out of “U Turn” [1997] and was replaced by Sean Penn because he didn’t understand his character.

How important are your three Oscars to you?

They look good in the corner. Memories. I think I’ve passed the level of merit. I see myself as a better filmmaker, although others may not agree. But the Oscars, it’s a game, you know. Oscar chasing is like high school politics where they want to be president of the class. I don’t like any of that.

You worked with a lot of great actors and big stars. Have you ever been starstruck?

Yes. When I was forty, I won an Oscar for [directing] “Platoon” [1986]. Liz Taylor presented me the Oscar on stage and then she kissed me. She was my sweetheart, my dream girl, during the 1950s and 1960s, so that was a special moment for me.

-FilmTalk interview with Oliver Stone, March 19 2024

0 notes

Text

“The Great Depression: A Sign of the Times,” 1932. A man carries a sign reading, “I demand my life savings $2950 from the Bankers Trust Co. 14 Wall St. NY.” Photo: Fred Zinneman via Bridgeman Images

1 note

·

View note