#Flag of the Federation of Patagonia

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

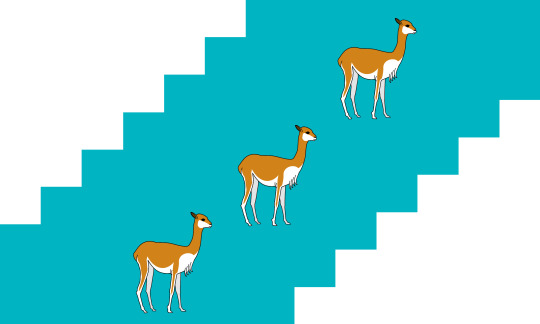

Flag of the Federation of Patagonia

This is the flag of the Federation of Patagonia. It comes from a world where Britain conquered Argentina and Uruguay in the early 19th Century. Patagonia is a highly developed nation, and is often referred to as the Canada of the Southern Hemisphere. Patagonia also includes part of southern Chile. Chile has never forgiven Patagonia for annexing this land. Though, this occurred during the days of direct British rule. The Falkland Islands are considered indisputably Patagonian territory.

Like Canada, Patagonia is the result of the bending of two European peoples. In this case, British and Spanish. However, also like Canada, said people have historically had their tensions. Northern Patagonia has historically been the heart of Hispanic culture. Meanwhile, Southern Patagonia has historically been majority Anglo. The name Patagonia used to refer to the region that became the southern provinces, but grew to refer to the nation as a whole. The ruling Anglos felt that Argentina and Plata were too Spanish for their taste. Hispanic Patagonians were pushed further and further north for much of the 19th Century. In fact, Buenos Aires and Montevideo used to be majority English-speaking cities. Though, Spanish speakers still accounted for a healthy forty percent of Buenos Aires and Montevideo’s population. Patagonia also experienced far less Italian immigration than Argentina did in our world. Catholic Italians weren’t eager to move to a colony of Protestant Britain. Subsequently, Patagonian Spanish has much less Italian influence than Argentina Spanish of our world. The northern provinces, initially, tended to be poorer than their southern counterparts. Things would begin to shift starting in the 20th Century. Industry began to invest in the northern provinces of Patagonia. The influx of industry lead to an increase in wealth among Hispanic Patagonians. Several baby booms occurred during this time, ensuring that Hispanic culture would survive in Patagonia. Hispanic Patagonians made major political gains in the Patagonian parliament. Bilingualism became official government policy starting in the 1950s. Packaging is required to be printed in both English and Spanish, signs are printed in both languages, and all government documents are printed in both of the official languages. There are also numerous Spanish-language schools and universities, though most are located in the Hispanic-majority northern provinces. Patagonia remains culturally divided among geographic lines. However, tensions have relaxed between Anglo Patagonians and Hispanic Patagonians. Patagonia is also home to immigrants from throughout the world, and prides itself on being a refuge for those seeking better lives. Patagonia has a friendly rivalry with Canada. Canada is referred to by Patagonians, with tongue planted firmly in cheek, as the Patagonia of the Northern Hemisphere. The flag was officially adopted in the 1970s. Prior to that, Patagonia used a British Red Ensign. Care had to be taken, when designing the new flag, not to favor Anglos or Hispanics. The colors evoke the landscape of Patagonia. The white represents the snow-capped mountains, while the ice blue represents the glaciers. The shape is meant to evoke the textile work of Indigenous Patagonians. The three guanacos were chosen as a symbol beloved by Patagonians of all cultures. In fact, the guanaco is the official mammal of Patagonia.

Link to the original flag on my blog: https://drakoniandgriffalco.blogspot.com/2023/02/flag-of-federation-of-patagonia.html?m=0

#alternate history#flag#flags#alternate history flag#alternate history flags#vexillology#alt history#Flag of the Federation of Patagonia#Patagonia#Britain#Argentina#Uruguay#Chile#South America#Great Britain#United Kingdom#UK#falkland islands#falklands

37 notes

·

View notes

Link

Two weeks ago, Sidd Bikkannavar flew back into the United States after spending a few weeks abroad in South America. An employee of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), Bikkannavar had been on a personal trip, pursuing his hobby of racing solar-powered cars. He had recently joined a Chilean team, and spent the last weeks of January at a race in Patagonia.

Bikkannavar is a seasoned international traveller — but his return home to the US this time around was anything but routine. Bikkannavar left for South America on January 15th, under the Obama Administration. He flew back from Santiago, Chile to the George Bush Intercontinental Airport in Houston, Texas on Monday, January 30th, just over a week into the Trump Administration.

He was detained by Customs and pressured to give up his phone and access PIN

Bikkannavar says he was detained by US Customs and Border Patrol and pressured to give the CBP agents his phone and access PIN. Since the phone was issued by NASA, it may have contained sensitive material that wasn’t supposed to be shared. Bikkannavar’s phone was returned to him after it was searched by CBP, but he doesn’t know exactly what information officials might have taken from the device.

The JPL scientist returned to the US four days after the signing of a sweeping and controversial Executive Order on travel into the country. The travel ban caused chaos at airports across the United States, as people with visas and green cards found themselves detained, or facing deportation. Within days of its signing, the travel order was stayed, but not before more than 60,000 visas were revoked, according to the US State Department.

Photo by David McNew/Getty Images

His ordeal also took place at a time of renewed focus on the question of how much access CBP can have to a traveler’s digital information, whether or not they’re US citizens: in January, the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) filed complaints against CBP for demanding that Muslim American citizens give up their social media information when they return home from overseas. And there’s evidence that that kind of treatment could become commonplace for foreign travelers. In a statement this week, Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly said that people visiting the United States may be asked to give up passwords to their social media accounts. "We want to get on their social media, with passwords: What do you do, what do you say?" Kelly told the House Homeland Security Committee. "If they don't want to cooperate then you don't come in."

Seemingly, Bikkannavar’s reentry into the country should not have raised any flags. Not only is he a natural-born US citizen, but he’s also enrolled in Global Entry — a program through CBP that allows individuals who have undergone background checks to have expedited entry into the country. He hasn’t visited the countries listed in the immigration ban and he has worked at JPL — a major center at a US federal agency — for 10 years. There, he works on “wavefront sensing and control,” a type of optics technology that will be used on the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope.

Bikkanavar’s reentry into the country should not have raised any flags

“I don’t know what to think about this,” Bikkannavar recently told The Verge in a phone call. “...I was caught a little off guard by the whole thing.”

Bikkannavar says he arrived into Houston early Tuesday morning, and was detained by CBP after his passport was scanned. A CBP officer escorted Bikkannavar to a back room, and told him to wait for additional instructions. About five other travelers who had seemingly been affected by the ban were already in the room, asleep on cots that were provided for them.

About 40 minutes went by before an officer appeared and called Bikkannavar’s name. “He takes me into an interview room and sort of explains that I’m entering the country and they need to search my possessions to make sure I’m not bringing in anything dangerous,” he says. The CBP officer started asking questions about where Bikkannavar was coming from, where he lives, and his title at work. It’s all information the officer should have had since Bikkannavar is enrolled in Global Entry. “I asked a question, ‘Why was I chosen?’ And he wouldn’t tell me,” he says.

The officer also presented Bikkannavar with a document titled “Inspection of Electronic Devices” and explained that CBP had authority to search his phone. Bikkannavar did not want to hand over the device, because it was given to him by JPL and is technically NASA property. He even showed the officer the JPL barcode on the back of phone. Nonetheless, CBP asked for the phone and the access PIN. “I was cautiously telling him I wasn’t allowed to give it out, because I didn’t want to seem like I was not cooperating,” says Bikkannavar. “I told him I’m not really allowed to give the passcode; I have to protect access. But he insisted they had the authority to search it.”

NASA

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Courts have upheld customs agents' power to manually search devices at the border, but any searches made solely on the basis of race or national origin are still illegal. More importantly, travelers are not legally required to unlock their devices, although agents can detain them for significant periods of time if they do not. “In each incident that I’ve seen, the subjects have been shown a Blue Paper that says CBP has legal authority to search phones at the border, which gives them the impression that they’re obligated to unlock the phone, which isn’t true,” Hassan Shibly, chief executive director of CAIR Florida, told The Verge. “They’re not obligated to unlock the phone.”

Nevertheless, Bikkannavar was not allowed to leave until he gave CBP his PIN. The officer insisted that CBP had the authority to search the phone. The document given to Bikkannavar listed a series of consequences for failure to offer information that would allow CBP to copy the contents of the device. “I didn’t really want to explore all those consequences,” he says. “It mentioned detention and seizure.” Ultimately, he agreed to hand over the phone and PIN. The officer left with the device and didn’t return for another 30 minutes.

NASA employees are obligated to protect work-related information, no matter how minuscule

Eventually, the phone was returned to Bikkannavar, though he’s not sure what happened during the time it was in the officer’s possession. When it was returned he immediately turned it off because he knew he had to take it straight to the IT department at JPL. Once he arrived in Los Angeles, he went to NASA and told his superiors what had happened. Bikkannavar can’t comment on what may or may not have been on the phone, but he says the cybersecurity team at JPL was not happy about the breach. Bikkannavar had his phone on hand while he was traveling in case there was a problem at work that needed his attention, but NASA employees are obligated to protect work-related information, no matter how minuscule. We reached out to JPL for comment, but the center didn’t comment on the event directly.

this is from an IRL friend of mine. this is NOT my america. EVER. #MuslimBan Siid is a US Citizen. @CustomsBorder u say "Welcome Home" #NASA http://pic.twitter.com/W4UtF88rJy

— Nick Adkins (@nickisnpdx) February 6, 2017

Bikkannavar noted that the entire interaction with CBP was incredibly professional and friendly, and the officers confirmed everything Bikkannavar had said through his Global Entry background checks. CBP did not respond to a request for comment.

He posted an update on Facebook about what happened, and the story has since been shared more than 2,000 times. A friend also tweeted about Bikkannavar’s experience, which was also shared more than 7,000 times. Still, he’s left wondering the point of the search, and he’s upset that the search potentially compromised the privacy of his friends, family, and coworkers who were listed on his phone. He has since gotten a completely new device from work with a new phone number.

“Sometimes I get stopped and searched, but never anything like this.”

“It was not that they were concerned with me bringing something dangerous in, because they didn’t even touch the bags. They had no way of knowing I could have had something in there,” he says. “You can say, ‘Okay well maybe it’s about making sure I’m not a dangerous person,’ but they have all the information to verify that.”

Bikkannavar says he’s still unsure why he was singled out for the electronic search. He says he understands that his name is foreign — its roots go back to southern India. But it shouldn’t be a trigger for extra scrutiny, he says. “Sometimes I get stopped and searched, but never anything like this. Maybe you could say it was one huge coincidence that this thing happens right at the travel ban.”

via The Verge

1 note

·

View note