#Filippo Lippi (1406-1469)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Lippo Lippi 🎨

Madonna and Child (1440) Tempera on Panel

Fra Filippo Lippi (1406 - 1469) Italian Painter

National Gallery of Art — Washington D.C.

#Madonna and Child#Fra Filippo Lippi#Painting#Religious Art#Virgin Mary#Christ Child#Jesus Christ#Renaissance#Tempera on Panel#Filippo Lippi#Art#Gallery#Lippo Lippi#National Gallery of Art#Museum#National Mall#Washington D.C.

66 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Filippo Lippi (Italian, 1406-1469) Madonna and Child with Two Angels, ca. 1460-65 The Uffizi

#Filippo Lippi#art#classical art#fine art#european art#christian art#angel#angels#christianity#virgin mary#christendom#christentum#the uffizi#italian#italian art#western civilization#fine arts#oil painting

129 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Adoration of the Infant Jesus 1465

Fra' Filippo Lippi (Italy 1406-1469)

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

MWW Artwork of the Day (12/18/23) Fra Filippo Lippi (Florentine, c. 1406-1469) The Martelli Annunciation (c. 1450) Tempera on wood Chiesa di San Lorenzo, Florence

Filippo Lippi's pictures show the naïveté of a strong, rich nature, redundant in lively and somewhat whimsical observation. He approaches religious art from its human side, and is not pietistic though true to a phase of Catholic devotion. He was perhaps the greatest colorist and technical adept of his time, with good draftsmanship. As a naturalist, he had less vulgar realism than some of his contemporaries, and with much genuine episodic animation, including semi-humorous incidents and low characters. He made little effort after perspective and none for foreshortenings, and was fond of ornamenting pilasters and other architectural features.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Filippo Lippi - (Firenze 1406 -1469), (detail) (Tempera painting) Galleria degli Uffizi Firenze, 1460 -1465 -

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Virgen y el Niño y relatos de la vida de Santa Ana Filippo Lippi (Florencia 1406 ca. – Spoleto 1469) Fecha: 1452-1453 c. Galería Palatina Técnica: Tempera sobre tabla Dimensiones: 135 cm (diámetro) Inventario: Inv. Palatina n. 343

Entre las composiciones sacras más originales del primer Renacimiento, el cuadro presenta en primer plano a la Virgen entronizada con el Niño sentado de rodillas, en el acto de arrancar las semillas de la granada que le ofrece la madre, símbolo de fertilidad y premonición de la pasión. Detrás del tradicional grupo de la Virgen y el Niño, en el interior de un palacio, se ambientan dos episodios de la vida de Santa Ana, madre de María. A la derecha de la escalera se narra el encuentro de Anna con su marido Gioacchino, mientras que a la izquierda se ilustra el nacimiento de la Virgen, con la nueva madre en la cama rodeada de mujeres ocupadas que la cuidan, cuidan al recién nacido y le traen regalos: es una visión veraz de la vida cotidiana de las mujeres de las clases más ricas en el siglo XV. Los diferentes tamaños de las figuras (más pequeñas las de Joaquín y Ana en el episodio del encuentro, intermedias las de los personajes que participan en el nacimiento de María y luego grandes las de la Virgen y el Niño colocadas en primer plano) miden, además a la profundidad espacial, la distancia temporal que separa los tres momentos. Filippo Lippi logra armonizar las partes individuales de la historia, narradas con una extraordinaria síntesis narrativa y unificadas por la compleja arquitectura de estilo renacentista. Se tiende a relacionar la obra con algunos documentos de 1452-1453 en los que Filippo Lippi recibió el encargo de ejecutar un tondo para Leonardo Bartolini Salimbeni (1404-1479), probablemente destinado a su residencia: la forma circular caracterizaba a menudo las imágenes sagradas de Destino doméstico durante el siglo XV y los temas representados también se adaptan bien a un contexto familiar. En la parte posterior del panel hay un boceto de un escudo de armas que representa un grifo, hasta ahora no identificado.

Texto por Daniela Parenti Información de la web de la Gallerie degli Uffizi, fotografía de mi autoría.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Da: SGUARDI SULL’ARTE LIBRO PRIMO - di Gianpiero Menniti

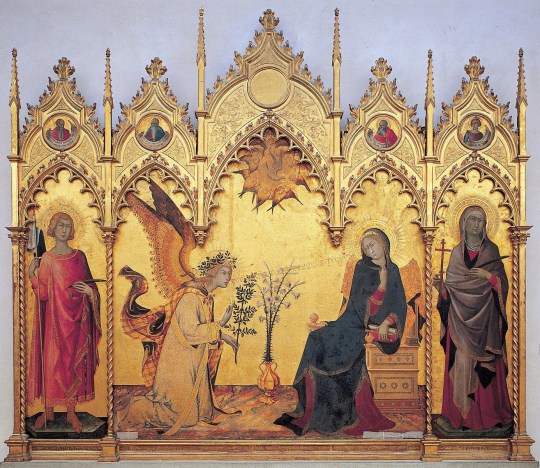

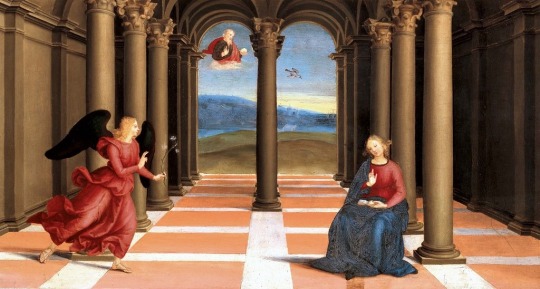

IL "SI'" CHE HA CAMBIATO LA STORIA

Non si riflette quasi mai sul ruolo di Maria Vergine nell'avvento della cristianità. La Madonna rappresenta l'origine, il necessario atto d'obbedienza che è accoglienza, sacrificio, carità, fede. Gli artisti ne compresero la portata immensa. Intuirono la potenza che scaturiva dall'umile incertezza della Vergine di fronte all'annuncio. Il presagio del calvario. Il timore della prescelta. L'atto di compassione. La dolcezza temeraria di madre. Senza quel "sì" nulla si sarebbe compiuto: quell'assenso è il primo atto d'amore che segna l'era cristiana.

- Simone Martini (1284-1344): "Annunciazione" (1333)

- Filippo Lippi (1406-1469): "Annunciazione" di Washington (1435, 1440)

- Piero della Francesca (1416-1492): "Annunciazione" di Arezzo (1452,1458)

- Antonello da Messina (1430-1479): "Annunciazione" (1474)

- Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510): "Annunciazione" di New York (1485)

- Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519): "Annunciazione" (1472, 1475)

- Pietro Perugino (1446-1523): "Annunciazione" di Fano (1488, 1490)

- Raffello Sanzio (1483-1520): "Annunciazione" della Pala Oddi (1502, 1503)

- In copertina: Maria Casalanguida, "Bottiglie e cubetto", 1975, collezione privata

#thegianpieromennitipolis#arte#arte italiana#simone martini#filippo lippi#piero della francesca#antonello da messina#sandro botticelli#leonardo da vinci#Pietro Perugino#raffaello sanzio#maria casalanguida

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Madonna von Fra Filippo Lippi (1406-1469); Galería de los Uffizien Florenz.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Filippo Lippi (1406-1469), Herod's Banquet.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Madone de l’Eucharistie par Botticelli — aufildelapensée

La Vierge à l’enfant par Botticelli Le fruit de la terre et du travail des hommes Alessandro Filipepi (1445-1510), surnommé Botticelli, commence à travailler comme orfèvre dans l’atelier de son frère aîné, Antonio. Il en gardera l’art du dessin net et précis, comme ciselé. À 22 ans, il entre dans l’atelier de Filippo Lippi (1406-1469). Là, pour […]La Madone de l’Eucharistie par Botticelli —…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Fra Filippo Lippi (1406 - 1469) - Virgin and Child.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Detail of the Madonna from the painting Madonna and Child with two Angels. 1465. Artist: Fra Filippo Lippi. Italian Early Renaissance Master Painter and teacher of Sandro Botticelli (1406-1469)

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Filippo Lippi (Italian, 1406-1469) Annonciation et deux donateurs, Détail, 1440 Galerie nationale d'Art ancien

#Filippo Lippi#italian#italian art#italy#mediterranean#european#europe#angel#cherub#greece#rome#vatican city#catholic#catholicism#germany#france#spain#uk#england#wales#scotland#art#fine art#blonde#halo#classical art#arte#europa#christian#christianity

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lippi’s Madonna and Child

Filippo Lippi (1406-1469)

Madonna and Child with Two Angels, 1460-1465 ca.

Tempera on wood

95x62 cm

The Uffizi Galleries

-----------------------------

Why I chose this piece

When thinking about what piece to choose, I was stuck for a few days. I felt that I did not have any objects in mind that were ‘strong enough” in their objection. Most of the art that I have studied has been within the European realm and, therefore, Eurocentric. I was not sure if a European piece would be as appropriate or powerful as a painting or sculpture from a culture that had been colonized by Europeans. However, as I thought about it more, I concluded that dismantling harmful ideas and stereotypes produced by Eurocentrism within Europe is just as crucial as dismantling them in previously colonized cultures.

I feel a deep connection to the Renaissance and Italian culture in my academic studies because of my undergraduate degree in Italian. I knew I wanted to carry what I learned during the last four years into my graduate work, and this project seemed like the perfect opportunity. There were lots of different artists and paintings that I could have chosen. There is Artemisia Gentileschi, a woman artist who rivals Caravaggio in skill and style. Or Elisabetta Sirani, another woman artist from the Renaissance who opened a painting academy for women. Their works contrast the Eurocentric norms of the time, by their status as women artists and the subjects of their art.

I chose Filippo Lippi’s piece for a few different reasons. The first is that it is my favorite painting from the Renaissance. The first time I heard the story behind the painting’s history, I was enthralled. Like the painting’s physical beauty, I thought the story was beautiful and liberating. My thoughts changed later upon hearing another version of the painting’s history, but for the most part, I still find myself caught up in the emotion of the original sentiment I studied. The second reason I chose this painting is its role in cementing some but contesting other Greco-Roman norms, many of which persist today. The Renaissance’s goal to reclaim ancient Greek and Roman culture and harmful Christian ideals created a dangerous and oppressive situation for women in the Renaissance. Since many cultures worldwide have been shaped by these same Eurocentric cultural aspects, I think the painting’s objection to women’s status at its time of creation makes it all the more powerful. Its power transcends time and is still important today.

This painting is by no means a perfect representation of Filippo Lippi or his character, as I describe in more detail below. However, I think it shows objection to religious and social ideas we abide by today, especially in Christian culture, that were seemingly cemented in the Renaissance. I also think it is an excellent piece to explore Eurocentric historicism, which I discuss below. I enjoyed revisiting my favorite Renaissance work of art, and it turned out to be the perfect piece for me in completing this project.

Reframing the object

Lippi’s Madonna and Child with Two Angels has been a symbol of resistance in my eyes since I first learned about it in my undergraduate Renaissance art history class. While the Renaissance was about breaking the rules, new rules regulated the breaking of those old rules. The push away from traditional religious iconography and imagery in the Renaissance did not mean that religious painting and sculpture commissions stopped--quite the opposite, actually. Biblical scenes and characters' secularization led to a boom in inspiration and production, with hundreds of annunciation, crucifixion, and “Madonna and child” scenes portrayed in the Renaissance style. These scenes were often inserted into a Tuscan landscape, depicting characters according to Italian beauty standards at the time.

Upon first glance, this painting may appear to be another standard “Madonna and child” from the early Renaissance. Mary, dressed in blue and seated in the foreground, adheres to the ideals of Renaissance beauty. With blond hair, a high forehead, and brown eyes, she depicts the ideal woman from this period. Her skin is also a pale cream, another ideal physical aspect of Italian society and art during the Renaissance. After the first glance, though, it becomes clear that Mary’s face is not the generic face of any particular Italian woman walking down the street. Her face is uncannily similar to the face of Lucrezia Buti, Lippi’s wife.

The act of using his wife as a model for the mother of God may not have been scandalous in and of itself. However, Lippi, an ordained priest, and Buti, a nun, had an affair that resulted in children out of wedlock. Historically, the narrative has been that Lippi kidnapped Buti during a public Catholic procession, taking her to his home in Prato, where their affair ensued. It is unclear whether the kidnapping was a front because Buti could not leave her convent, or if it was an actual kidnapping, meaning she was held against her will and raped multiple times. Most of what we know about Lippi and Buti comes from Giorgio Vasari’s The Lives of the Artists, a collection of biographies published in 1550 written about the best artists of the Renaissance. Vasari was known to exaggerate and alter stories for his dramatic literary gain. He was also a raging sexist, excluding numerous successful and famous women artists from his work. How much of Lippi and Buti’s story is true is up for debate.

Lippi and Buti’s statuses in the Catholic church made their affair extremely scandalous, even by Renaissance standards. Themes of carnality and sexual liberation were increasingly common in art and literature, but purity, modesty, and virginity remained crucial aspects of religious life. Lippi and Buti’s children, who were born out of wedlock, were proof of their Catholic faith's betrayal. As punishment, they should have been exiled from Florence at the very least. The Medici family, who ruled Florence and the surrounding villages, allowed Lippi and Buti to remain in the city and live as a typical family so long as Lippi completed painting commissions at the family’s request. With their significant political influence and artistic patronage, the Medici family acquired a special dispensation for Lippi and Buti to marry. It is unclear whether they ever did, which would have only added to the shame of their domestic and religious situation.

It is impossible to ignore the possibility that Buti may have been a victim of sexual assault in this story. If it is true, Lippi’s work cannot be separated from his status as a rapist. However, given that there is no clear evidence that he is or is not, the more common narrative that he kidnapped Buti because she could not leave the convent and that they truly loved each other has persisted. This being the standard narrative speaks volumes to the ways history is written to protect and favor men.

Using Buti as his model for Mary, Lippi smashes the expectation that women should be modest and pure. His wife, a disgraced nun and mother of bastard children, is the face of the mother of God. Lippi objected to harmful and sexist gender roles in doing this. Mary has long since been the “ideal” feminine model for women living within the Christian sphere. Her veneration, which partially stems from her virginity, has been used to keep women sexually repressed and stuck in submissive social and domestic roles.

Patriarchy and its harmful consequences cannot be separated from Eurocentrism. In reframing Lippi’s Madonna and Child with Two Angels, I would like to apply Dipesh Chakrabarty’s theory regarding Eurocentrism and historicism. If we look at this painting and the traditional narrative of Mary, Christianity, and women’s roles, it goes against Eurocentric historicism. A woman like Buti would be considered a whore to most people during the Renaissance, even though she is possibly a survivor of sexual assault.

Religion, sex, and patriarchy do not exist in a vacuum. Nor are they determined by history. We make decisions every day (conscious and unconscious) that uphold the harmful effects of negative sex representation in patriarchal religious settings, much like those in the Renaissance did. This was not because people did not “know any better.” Scholarship and rhetoric surrounding women’s rights and freedom were relatively well-circulated during the Renaissance. Books like Christine de Pizan’s The Book of the City of Ladies set forth numerous arguments for women's liberation and their various essential roles in society. Like today, people chose to use tradition and “history” to continue reinforcing harmful stereotypes, expectations, and ideals for women.

Lippi and Buti’s story is complicated. We will never know what truly unfolded nearly 600 years ago, mainly because the male-centered narrative has persisted in their case. However, Lippi’s painting does object to religious standards of the time. With his painting, a woman can be held with the highest regard, regardless of her sexual past. It goes against the Eurocentric patriarchal tradition and breaks away from the European historicism that claims women’s treatment was shaped solely upon the cultural norms of the past that peristed in the Renaissance. This piece is one of the most famous works from the Renaissance, and it is still widely celebrated today. Its place in art academia makes it a piece of persisting resistance that can serve as inspiration to break away from gender norms in religion and society today, as Lippi and Buti did so many years ago.

--Darian Rahnis

1 note

·

View note

Photo

MWW Artwork of the Day (12/26/22) Fra Filippo Lippi (Florentine, c. 1406-1469) Madonna and Child with Two Angels (c. 1460-65) Tempera on panel, 95 x 63.5 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

This extremely well-known and even popular work has always been considered as one of the highest and most lyrical expressions of Lippi's art. The element of design is so greatly emphasised in this painting that it seems almost the artist's only means of expression. His colour creates a soft light, and the play of light and shade, plus the transparency of the veils, creates the illusion of movement rather than of substance. In the context of this soft light, the suggestion of modelling in the face of the Madonna seems hardly more than a tremor. The delicate profile of the Virgin Mary, seated by the window, is outlined clearly against the rocky landscape, while two angels hold up the Christ Child, who reaches toward his praying mother. The angel in the foreground turns with an odd smile toward the spectator.

For more of this artist's work, see this MWW gallery/album: https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.464125917026116&type=3

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Filippo Lippi - (Firenze 1406 -1469), (detail) (Tempera painting) Galleria degli Uffizi Firenze, 1460 -1465 -

27 notes

·

View notes