#Eugène Chaperon

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Eugène Chaperon: La douche au régiment

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Józef Poniatowski’s children and descendants

Because a couple of months ago there’s been a discussion about Napoleon marshal’s children I decided I out to share with you the info about Józef Poniatowski’s issues and descendance.

Though never married, prince Józef nevertheless had two illegitimate sons.

The oldest one was Józef Szczęsny Mauricy Chmielnicki, born on the 17th of September, 1791.

The mother of the boy was most probably Poniatowski’s mistress of that time, the actress named Małgorzata Magdalena Wiktoria “Zelia” Sitańska (though there are as well versions it might have been another woman, for example, Zelia’s step-mother, also an actress - more on the topic I wrote here)

Zelia and here step-mother, a colored engraving

As for the fate of the boy - in his youth (before 1807) he started a military career in the Army of... Austria. Most probably it was prince Józef himself who arranged it, because his career started in the Austrian army too. (Another question is why Poniatowski didn’t “transfer” his son into the Army of the Duchy of Warsaw after the latter had been created, but, I’m afraid, we’ll never know the answer.)

And when in 1809 Austria attacked the freshly created Duchy, Józef Chmielnicki took part in the war... on the side of the Austrians. (And his father kinda accepted this, because in his will written 3 years later, in 1812, Poniatowski mentioned not only his firstborn but as well the fact that the latter was an officer in the Austrian Army.)

Chmielnicki fought as well in the next coalition wars, in 1812-1815 (against Napoleon as well), in 1831 he fought in defense of the Roman ecclesiastical state against local insurgents; for this he received the papal Order of St. Gregory. He also had the Austrian Military Cross. In 1856 he retired with the rank of colonel. He died unmarried in Vienna in 1860.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to find any image of Józef Chmielnicki, but in his military service records there is a little bit on his appearance:

Tall, of good health, very lively temperament and honest and reliable character. Polite and tidy; sometimes a bit violent and not always consistent. Zealous and active, with a special penchant for service in rifle units. He was wounded twice. He is fluent in German and Polish in speech and writing, speaks French and a little Italian. A very good staff officer, suitable for a regiment commander.

More do we know about Prince’s Józef’s other son, who was born on the 18th of December, 1809 in Warsaw and was then was given the name Józef Karol Ponitycki.

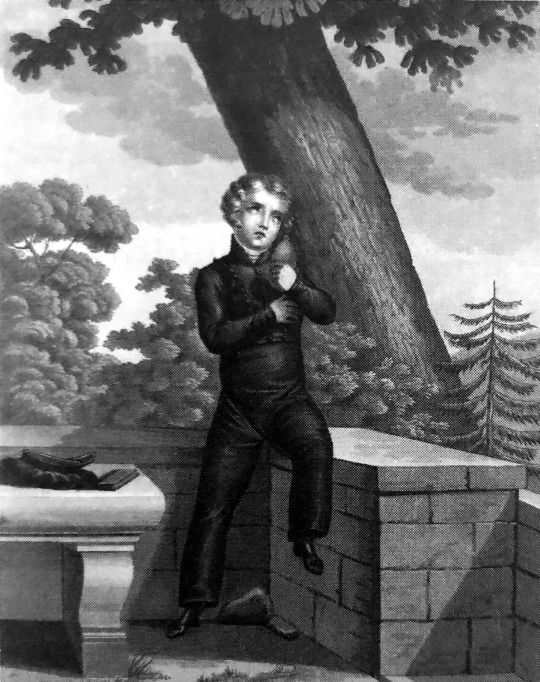

Józef Peszka, Portrait of Józef Ponitycki, 1815

As for Józef the second mother - there are no doubts in it, it was prince Poniatowski’s another mistress, Zofia Czosnowska née Potocka (more about her - here).

Though Czosnowska was married, prince Józef acknowledged her child and mentioned him in his will.

A miniature showing Ponitycki at the age of ten

The boy’s mother, however, didn’t care for her child much. Having divorced her official husband she married again in 1815, then placed her son in the custody of his aunt, prince’s Józef sister countess Maria Teresa Tyszkiewicz.

In the 1821 countess Teresa became the boy's legal guardian (Czosnowska officially gave him up) and in 1828 adopted him, changing his surname from Ponitycki to Poniatowski and adding Maurycy (Maurice) as his third name, thus making the boy the namesake of her long-term love Charles Maurice de Talleyrand.

And a little bit before, in 1826, Józef the younger gained French citizenship, and at the age of 18 (1827) he volunteered to join the French army.

An anonymous painter, Prince Józef's son grieving after his father, 1820

The enlistment papers say that he was a healthy, blue-eyed, tall (1.79 m) blond, oval face, strong chin and aquiline nose. After graduating from school, he took part (as chasseur sergeant) in the Greek campaign in the Peloponnese (1829), later he was transferred to Algiers (1830), but he quickly returned to France.

During the July Revolution in Paris that year Poniatowski was among those soldiers who were putting it down, but when a year later the November Insurrection broke out in Poland he, together with his friend, Count of Montebello, a son of the Marshal Lannes, went to Poland to join the uprising. After the fall of the uprising, Józef returned through Galicia to France, where joined the rifle regiment as a captain and took part in the war in Algiers with Abd del-Kader in the years 1832-1836.

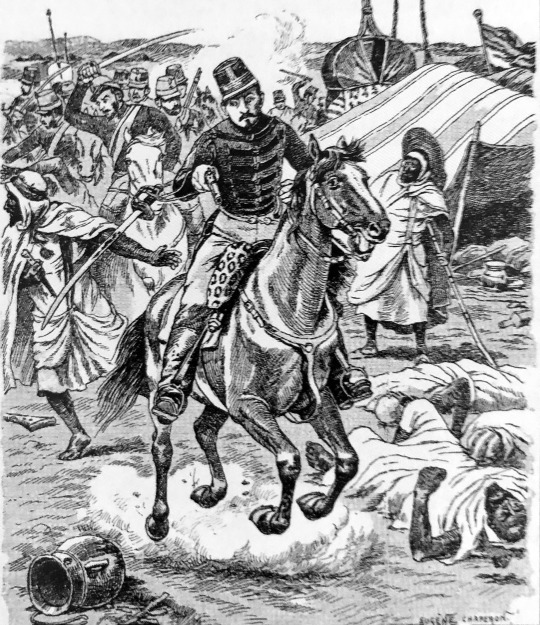

Józef Ponitycki-Poniatowski charges the camp of Emir Adb-el-Kader, a drawing by a French painter Eugène Chaperon

In 1839, driven by longing for his homeland, Poniatowski came to Kraków and made efforts to obtain permission to return to Warsaw. But the Russian Governor Paskevich refused him entrance and even tried (unsuccessfully) to confiscate) properties Józef inherited from his father and aunt.

Not being allowed to return to Poland, Poniatowski returned to France and to his regiment. He died on February 15, 1855 in Tlemcen, Algeria, and was buried there.

As for Józef Karol Poniatowski’s private life - in 1836 he married an Englishwoman, Maria Anna Semple. They have two children - a son, Józef Stanisław, born in 1837, and a daughter, Maria Teresa, a year younger.

Józef Stanisław joined the army at the age of 17 and went on the Crimean campaign. During the siege of Sevastopol, he was appointed lieutenant for his bravery. He then served in the cavalry regiment. He left the service due to ill health. In 1866 he married Léonide Marie Victoria Charner, the daughter of a French admiral, the chief commander of a sea expedition to China.

Six weeks after his marriage with Léonide Charner in 1866 he became mental ill. From 1880 until his death July 20, 1910 in Geel, Belgium, where he resided as a psychiatric patient in the wellknown Geel "Colonie des Aliénés''. (Many thanks to Werner for providing me with this information).

As for Józef Stanisław’s issue - there we have a kind of discrepancy. According the Polish sources like, for example, the Genealogy of the Descendants of the Great Sejm , he died childless but according his profile at geni.com he did have a son, named André whose descendants still live in the US. (The site doesn’t allow to see all the data but it is highly probably that the direct male line continues till our days.)

Maria Teresa, after the death of her father, was taken care of by the Duchess d'Eckmühl, the widow of the Marshal Davout. In 1859, Maria Teresa married Louis de Guirard, Comte de Montarnal, grandson of Marshal Ney. He was an official in the Ministry of Treasury. They had seven children: three sons and four daughters. But neither of those, according both the Genealogy of the Descendants of the Great Sejm and Geni.com had issue.

What’s more, according Geni.com Józef Karol Poniatowski after the death of his first wife married again. That time he took as a wife a woman named Elżbieta Fuchs, and they have a son named Wojciech Józef. That Józef, it looks like, was married, but no information about his issue is provided.

#Poniatowski#józef poniatowski#zelia sitańska#Józef Szczęsny Mauricy Chmielnicki#zofia czosnowska#Józef ponitycki#józef karol maurycy poniatowski#józef poniatowski's children#józef poniatowski's descendants#józef peszka#eugène chaperon

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eugène Chaperon - The shower at the Regiment (1887)

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eugène Chaperon, La Douche au Régiment, 1887

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

EUGÈNE CHAPERON Paris, Assault by Murat at the head of his battalion

1 note

·

View note

Text

I had not quite imagined Murat's domain to look like this,

Eugène admits to Bessières. As their two horses trot leisurely along the narrow cobblestone alleys, to his great surprise he feels almost entirely at ease. Sunlight paints the somewhat rundown houses golden, the air still smells like spring, there's a light breeze coming up from the river.

He does not know what he has expected on learning that they would see an afterlife à la Murat. Probably something very colourful. Maybe Naples, the most beautiful city of the Mediterranean, the Gulf of Naples in all its breathtaking azure glamour, the island of Capri, a smoking Vesuvius in the background. Or maybe a large stud farm. In his worst moments, he has imagined he will enter a huge wardrobe, nothing but clothes in bright and clashing colours, feathers and golden embroidery.

But this? It's as unlike the exuberant, ostentatious "Roi Franconi" as Eugène can imagine. It's almost ... serene.

He does not quite remember if he's come here before when he accompanied Bessières, playing, as they had joked, the chaperone when Bessières visited his future bride. But towns in Southern France like this one he has seen before, and he genuinely enjoys its atmosphere.

It takes a while until he realizes that this afterlife, too, has its peculiarities, its quirks, just like Lannes'. His head whips around when, for a heartbeat only, but crystal clear and without any doubt, an illumination lights up on the wall next to him, in a strange green light brighter than any other illumination he has ever seen. A reflection in the window of a shop shows him a young woman, wearing a man's clothes and holding a little boy by the hand. But when he turns around, there's an old lady, her head covered by a fringed scarf, sitting on a bench and sending him a toothless smile.

It's as if a strange second life flickers into the happy picture before Eugène's eyes. And whenever it touches him, whenever the light of another wall illumination falls on him, or when he has to move out of the way of somebody balancing and going incredibly fast on a strange, slim two-wheel vehicle, he feels his strength waver, his view blurring, his throughts getting muddled. Somebody looking at him in such a moment might see him briefly turn pale, or rather grey, losing colour like a faded drawing.

But that's over in the blink of an eye. As soon as the image of 18th century Cahors is back, so is he.

Where do we need to go?

Something Old, Something New

Previously: The Prince and the Hunter (1, 2, 3, 4)

Here, in the domain of the King of Naples, except for one day of the year, the sun never sets. Except for one day of the year, the weather is reminiscent of the last days of spring, before the heat of summer rises.

Like time captured in a bottle, the domain of the King of Naples is the village of Cahors as he had known it in his youth, when he'd been sent there to attend school. There is the ancient bridge over the River Lot called the Pont Valentre where he and the young Bessières would spend long hours dangling fishing lines off of on those days they were free to roam. And the Cathédrale Saint-Etienne, already nearly a millennium old before either of them had been born. The town jail known as the Château de Roi, and the Église Saint-Barthélemy, and the old watermill, the Moulin St-James.

The Cahors of Murat's memory hugs the eastern side of the U-shaped bend of the River Lot. And if one takes time to watch, an observer may see the intrusions. For the Domain of Murat is but a layer, a separate dimension, if one will. It is the land of the dead, the past, and ghosts, separated by a porous boundary from the world of the living.

The land of the living intrudes upon the land of the dead. Like bright afterimages, the immaterial shapes of artifacts and people from the present Age of Man glimmer briefly and vanish. One of those self-propelled carriages called a car, or a moped, or perhaps a lost pair of tourists leave behind luminous impressions upon the land of the dead. Stop to stare through a glassmakers' shop window from Murat's time, and one might find it suddenly replaced by the large windows of a shop hawking mysterious and arcane artifacts from the Present Age. And then, just as quickly, the shop front will revert once more.

Some artifacts from the Present Age, and the ages before, will find their way into the domain of the King of Naples, slipping through the cracks in reality between worlds. People are as ever forgetful, and they forget where they leave their wallets, their passports, their keys, their precious jewelry. They forget them, they lose them, and these artifacts turn up in Murat's domain. The crypt beneath the Cathédrale Saint-Etienne is well-stocked and open to any of his fellow dead who might think they might have something there they may need or want.

So too locations and buildings that may not have been built during Murat's time as a living man also find their way into the land of the dead. Here is a central plaza, where the living hold festivals and gatherings. And at one end of the plaza is a tranquil fountain, where a bronze statue of Neptune presides over a natural spring. Squint, and you might see the living world, shimmering like mirages in the desert, two statues flanking the spring's entrance: a statue of Joachim Murat, and a statue of Jean-Baptiste Bessières.

( @rapports-de-combat, @le-fils)

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Vision (The Vision) by Eugène Chaperon (1922)

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Glorious Trophies by Eugène Chaperon

#napoléon bonaparte#napoléon#napoleonic#napoleonic wars#napoleon#bonaparte#art#painting#history#europe#european#captured#banners#flags#trophies#france#empire#eugène chaperon

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Eugène Chaperon, La douche au régiment, 1887

63 notes

·

View notes

Photo

‘La douche au Régiment’, c.1887 by Eugène Chaperon (1857–1938). French painter, draftsman and printmaker. oil on canvas.

545 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi ! Who was Eugène friends with throughout his life and were there people with whom he was not so friendly? How was your relationship with your wife's family? Thank you!

Hi there, and thanks for the question! Also, please bear with me, ´coz this is going to be lengthy.

Eugène's position changed a lot over the years but there are some people, usually not well-known, who will remain friends with him throughout all his life.

During the Consulate, Eugène was something like everybody's darling. This was partly due to his position as stepson of the new chief of state. First Consul Bonaparte increasingly resembled a monarch, and Eugène, the son of Madame Bonaparte,was the closest thing to a crown prince there was. Eugène's biographer Michel Kérautret emphasises how much he (and in a different vein his sister) were seen as the »next generation of France«. Eugène commanded one of the most famous regiments, the Chasseurs au Cheval de la Garde, and was universally admired. Little boys looked at him with big eyes when he walked by. Besides, he was completely apolitical, only interested in women, horses and the army, and could therefore be invited by anyone. As long as there was music and dancing, Eugène was happy.

His closest friends also came from the ranks of the army. His probably best friend is hardly known: Auguste Bataille (de Tancarville), later Baron of the Empire and one of Eugène's aides-de-camp. Napoleon was not very enthusiastic about him and his abilities. (If I remember correctly, poor Bataille once had the misfortune to have a thief steal the briefcase with the documents he was supposed to bring to Napoleon. Eugène then got a nasty letter saying "Don't send me that idiot any more!")

Auguste Bataille remained in Eugène's service until his death in 1821. He is the one Eugène sends to Napoleon in 1809 to report the arrival of the Armée d'Italie in Austria (when Eugène was probably expecting the thrashing of his life and instead received a hero's welcome). But he is also the one whom Eugène's sister and wife turn to when they want news of Eugène and he himself has no time to write, so clearly someone who is quasi-family. When Eugène had to leave Italy, Bataille, who was married there, remained behind to administer Eugène's Italian properties. He died in 1821, and when Planat de la Faye asked Eugène for a job in 1822, Eugène explicitly referred to the late Bataille and said "You have seen who else belongs to my entourage. Bataille was my friend and the only one I could really rely on - I want someone like that again." (Planat de la Faye will take this job very seriously and later defend Eugène's memory like a bloodhound).

Just to mention a few other people who became important to Eugène since his time in Italy and who also accompanied him to Munich into exile: his cousin Louis Tascher and his wife, his adjutant General Triaire and the family of his former secretary for political affairs, Etienne Méjean and his only remaining son. After Eugène's death, Eugène’s children will grow up with the children of Méjean Jr.; they will call them "Papa Méjean" and Grand-Papa Méjean".

Let's move on to more prominent people. Among the marshals, Eugène's best friend was clearly Bessières. Bessières had been Eugène's superior since Egypt and remained so until Eugène went to Italy as viceroy. Apparently Napoleon had tasked Bessières with taking Eugène under his wing (or perhaps just with preventing his overzealous stepson from accidentally killing himself in the Sahara in an attempt to somehow distinguish himself). This resulted in a friendship that lasted for years. Eugène called Bessières "tu" in his letters, even when he had become prince and viceroy; there are apparently over a dozen letters to him in the "Archives Nationales", which are according to the description "of a predominantly private nature". After returning from Egypt, Eugène and Bessières shared a house in Paris (and apparently the two also plunged into Paris nightlife together). Eugène also accompanied Bessières when the latter visited his fiancée in Cahors and repeatedly sent his regards to Madame Bessières. After Bessières' death, there were several letters of condolence between Eugène and Bessières’ widow. In his memoirs, Eugène defended Bessières against some accusations that Lannes had made against him after the battle of Marengo. (One would think that this would have been time-barred by 1823).

Duroc, from whom Eugène sometimes sent greetings in his letters to Hortense, completed the trio of friends (but Duroc seemed to get on well with everyone). Eugène recounts in his memoirs how Duroc once stopped him from literally sleeping through his duty in Egypt; later they lay wounded side by side in the military hospital outside Acre (Duroc, however, considerably worse). When Eugène was left all alone and clueless in Milan as Viceroy of Italy (that was how he saw the matter), Duroc seems to have been the only one who regularly looked after him and wrote to him. Apparently Duroc and Eugène also "shared" the attentions of a young lady from the stage (Emilie Bigottini). Later, whenever Napoleon was particularly angry with Eugène (which happened with a certain frequency), he did not write to him himself, but had someone else write; usually it was Duroc. Duroc was also the one who delivered the marriage proposal to Eugène's prospective father-in-law. When Eugène was in Vienna in 1809, he wrote an enthusiastic letter home to his wife because he had finally, for the first time in three years, been dining together with Bessières and Duroc! (Funnily enough, Bessières wrote almost the same letter to his wife).

However, Eugène's oldest friend among Napoleon's close collaborators, who even became his relative, was Lavalette. When Eugène, not quite 16 and just out of school, went to Italy as Napoleon's adjutant, the first Italian campaign was basically over. Napoleon sent his stepson to Corfu with dispatches (and explicit orders to get some rest and sightseeing there), and gave him Lavalette as an escort. Before the Egyptian campaign, when Lavalette was to ask for the hand of Emilie de Beauharnais, Eugène had to chaperone him and his cousin for a walk, only to remember that he had urgent business elsewhere and leave them alone. Lavalette was also among those whom Eugène continued to address as "tu" in his letters after he was promoted to viceroy. And after Lavalette narrowly escaped execution in the Second Restoration, he took refuge with Eugène in Bavaria, where Eugène and King Max more or less successfully hid him.

I'm limiting this to Eugène's male friends, by the way. Female acquaintances are another matter altogether.

Who did Eugène not get on so well with? Quite a lot of people, interestingly enough, consideringhe is described in almost all sources as incredibly amiable, patient and sociable.

There is, of course, his rivalry with Murat, the exact origins and background of which would interest me immensely. The two were actually in a very similar position from 1810 on at the latest, but rather than communicating with each other, the two seem to have been constantly at each other's throats. I have the impression that Murat made a timid attempt at reconciliation now and then, and that at this stage Eugène was the one who no longer wished to hear anything from Murat. Probably because he held Murat responsible for Napoleon's separation from Josephine.

And only to avoid any false impression: Murat and Eugène also called each other "tu" when they met in private. But in their official correspondence, they almost suffocate from the pompous phrases they throw at each other.

Someone Eugène did not get on with at all was Marshal André Masséna. For this, I think alot of things came together: a social background that couldn't be more different, and perhaps a sense of class superiority on Eugène's part. On the other side, Masséna, who had really fought his way up from the gutter by his own efforts, was unlikely to have taken seriously this brat who, thanks to his stepdad, was allowed to play viceroy in Italy. Eugène, for his part, with his rather naïve attitude to war, was horrified by Masséna's ... rather creative approach to the subject of requisition and his general attitude to "mine" and "yours". In 1805 he complained bitterly about the way Masséna and his men had plundered the Italians they were supposed to protect, and Masséna actually had to pay back a huge amount of money. In 1809, Eugène desperately wanted no marshal (it would probably have been Masséna) to be sent to Italy, but to be allowed to take command himself. When the battle of Sacile promptly turned into a disaster, Napoleon told him pointedly that this would not have happened with Masséna, Masséna’s plundering notwithstanding.

Similarly, Eugène clashed with Auguste Marmont. This was also about money, financial trickery and personal enrichment. On this point, Eugène did not joke (and presumably this was precisely the reason why Napoleon had appointed him as overseer in Italy). The friction with Marmont developed into an enmity that lasted truly until after the death of the two adversaries, or rather only really erupted there: Marmont accused Eugène in his posthumously published memoirs (not entirely without reason, but in a rather exaggerated manner) of having been the main reason for Napoleon's defeat in 1814, and Eugène's daughters and Planat de la Faye (see above) then took the editor of the memoirs to court. Absolutely crazy.

From his correspondence, I take it he also at least once discovered Bourienne’s financial shenanigans in Hamburg.

I unfortunately do not know how his relationship with Marshal Lannes was (but I would love to know). My gut feeling says: probably similar to Masséna. Eugène does mention Lannes twice in his memoirs, both times respectfully. But I have not come across any personal interaction or correspondence between them at all. As Lannes was close to Murat and somewhat at odds with Bessières, he’s unlikely to have been friends with Eugène.

As this has gotten so long already, I’ll stop here and put anything about Eugène’s Bavarian in-laws into an extra post at a later date. Just so much for now: If this was Facebook, I’d pick »It’s complicated«.

#eugene de beauharnais#napoleon#auguste bataille#etienne méjean#jean baptiste bessières#jean lannes#antoine marie lavalette#geraud christophe michel duroc#andré masséna#auguste marmont

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Countess Potocka witnesses a tragedy

Here the Countess recount a much less happy event connected to the marriage of Napoleon and Marie-Louise. I have not researched how many died on this occasion, but even one was too many:

Le prince de Schwatzemberg [sic], ambassadeur d'Autriche, n'avait consenti à céder le pas qu'à la belle-soeur de la nouvelle Impératrice. Le bal qu'il donna suivit de près la fête de Neuilly et dut sa célébrité à l'horrible catastrophe qui le rendit historique. Le local de l'ambassade n'étant pas assez vaste pour que les deux mille personnes invitées pussent y trouver place, on avait construit au milieu du jardin une énorme salle de bal communiquant avec les appartements au moyen d'une élégante galerie. Cette salle et cette galerie, bâties en planches, étaient couvertes en toile goudronnée et décorée intérieurement de draperies de satin rose et de gaze d'argent. - Je me trouvais dans la galerie au moment où le feu se déclara, et je dus peut-être mon salut à un incident qui m'avait vivement contrariée. J'avais une robe de tulle uni au bas de laquelle un bouquet de lilas blanc était rattaché à ma ceinture par une chaîne en diamants composée de lyres accrochées les unes aux autres ; quand je dansais, cette chaîne se défaisait ; la comtesse de Brignole, qui me chaperonnait ce soir-là, voyant que j'allais valser avec le vice-roi, voulut bien m'emmener dans la galerie et m'aider à enlever cette malencontreuse chaîne. Pendant qu'elle avait la bonté de s'occuper de ce soin, j'aperçus, une des premières, la légère fumée produite par un candélabre posé au-dessous d'un feston de gaze ; plusieurs jeunes gens s’étant groupés autour de nous, je m'empressai de leur faire remarquer ce qui n'était encore qu'une menace. Aussitôt l'un d'eux s'élança sur une banquette ; voulant prévenir le danger, il arracha avec violence la draperie qui, en s'abaissant subitement au-dessus de la girandole, prit feu et communiqua la flamme au plafond de toile goudronnée. Fort heureusement pour moi, madame de Brignole n’affronta pas le danger et, sans attendre une minute, s'empara de mon bras, traversa en courant tous les salons, se précipita au bas de l'escalier, et ne reprit haleine qu'après avoir traversé la rue et s'être réfugiée dans l'hôtel de madame Regnault, situé vis-à-vis de l'ambassade. Là, tombant sur un fauteuil, épuisée par la course et l'émotion, elle m'indiqua le balcon afin que je lui rendisse compte de ce qui se passait. Je ne comprenais rien à ce soudain effroi, car j'eusse volontiers continué à danser, tant il me semblait impossible qu'un danger sérieux nous menaçât dans un lieu où se trouvait l'Empereur! ...

Bientôt des bouffées de fumée enveloppèrent la salle de bal et la galerie que nous venions de quitter. La musique ne se faisait plus entendre, une confusion bruyante avait succédé sans transition à l'éclat de la fête. Les cris, les gémissements arrivaient jusqu'à nous ; le vent apportait des paroles distinctes, des accents désespérés ; on s'appelait, on se cherchait, on voulait se rassurer sur le sort de ceux qu'on aimait et qui couraient cet horrible danger.

Au nombre des victimes se trouva la princesse de Schwartzemberg, belle-soeur de l'ambassadeur, qui, ne voyant pas sa fille à ses côtés, se précipita dans les flammes ; - elle fut écrasée par un lustre dont la corde avait cédé. Hélas ! son enfant, à l'abri du danger, l'appelait à grands cris... [...] Plusieurs femmes se trouvèrent dépouillées de leurs bijoux ; des filous ayant escaladé le mur qui sépare le jardin de la rue, exercèrent leur métier en toute sécurité, à la faveur de la confusion générale.

En peu d'instants le salon de madame Regnault de Saint-Jean d'Angely se remplit de blessés. C'était un spectacle à la fois terrifiant et bizarre de voir toutes ces personnes couronnées de fleurs, en robe de bal, se livrant à des gémissements qui contrastaient cruellement avec leur parure.

Nous passâmes ainsi une grande partie de la nuit à les consoler et à les soulager autant qu'il fut en notre pouvoir. Lorsque vint le jour, il fallut bien s'en retourner. Gens et voitures, tout avait disparu. Celles qui pouvaient marcher se trouvèrent réduites à s'en aller à pied en costume de bal et en souliers de satin blanc. A cette heure matinale, les rues sont encombrées de charrettes de maraîchers ; on nous prit probablement pour des folles, et nous eûmes à subir des bordées de lazzi.

Quelque légers que soient les Parisiens, cette catastrophe produisit une vive et profonde impression. Elle donna lieu à des propos de tout genre ; on voulut y voir les combinaisons d'une infâme politique. Ce qu'il y a de certain, c'est que des courtisans zélés avaient engagé l'Empereur à se retirer avant que la foule eût envahi toutes les issues, essayant de jeter dans son esprit un soupçon odieux ; mais, toujours calme dans le danger, Napoléon ne prêta point l'oreille à ces mesquines insinuations ; il rentra à l'ambassade après avoir mis l'Impératrice en voiture, disant au prince de Schwartemberg qu'il venait l'aider à éteindre le feu.

Ce mot produisit un grand effet, pénétra les Autrichiens d'admiration et de reconnaissance. Tous les Allemands présents à la fête, l'ambassadeur en tête, entourèrent l'Empereur, et ce rempart de coeurs plus ou moins ennemis valait pour le moment un détachement de la garde impériale.

The prince of Schwatzemberg [sic], ambassador of Austria, had consented to come second only to the sister-in-law of the new Empress. The ball he gave followed closely the fête of Neuilly and is still remembered for the horrible catastrophe which made it historic. The premises of the embassy not being large enough to accommodate the two thousand guests expected to attend the celebrations, an enormous ballroom had been built in the middle of the embassy's garden; this ballroom was connected to the embassy proper by an elegant gallery. The ballroom and the gallery, built out of wooden planks, were covered in tarred cloth; they were draped inside with pink satin and silver gauze. - I was in the gallery when the fire broke out, and I may have owed my salvation to something that gave me much annoyance. I was wearing a dress of plain tulle, at the bottom of which a bouquet of white lilac was attached to my belt by a diamond chain made up of connecting lyres; when I danced, this chain kept coming undone; the countess of Brignole, who was my chaperone that evening, seeing that I was about to waltz with the viceroy [Eugène], agreed to come with me to the gallery to help me remove this bothersome chain. While she was kindly taking care of this, I was one of the first to notice the light smoke emanating from a candelabra placed under a drapery of gauze; several young people had gathered around us, and I promptly brought to their notice what was still only a possible danger. At once one of these young men leapt onto a bench; meaning to prevent any danger, he tore off the drapery, which fell upon the candelabra, caught fire, and transmitted the flame to the tarred cloth ceiling. Fortunately for me, Madame de Brignole decided to flee the danger and, without an instant's delay, grabbed my arm, ran through all the embassy's salons, rushed down the staircase, and only stopped to regain her breath after crossing the street and taking refuge in Madame Regnault's house, located opposite the embassy. There, falling into an armchair, exhausted by the racing and the emotion, she motioned me to the balcony so that I could give her an account of what was happening. I could not comprehend Madame de Brighole's sudden fright; I would have willingly continued dancing, so impossible it seemed to me that we could be threatened with any serious danger in a place where the Emperor was present!

Soon wafts of smoke enveloped the ballroom and the gallery we had left moments before. The music had gone silent; noisy confusion had succeeded without transition to the brilliance of the celebrations. We heard screams and moans; distinct words uttered in desperate tones were carried by the wind; people called out to each other, sought each other out, wanted to reassure themselves about the fate of their loved ones left in such horrible danger.

Among the victims was the Princess of Schwartzemberg, sister-in-law of the ambassador, who, not finding her daughter by her side, rushed into the flames; - she was crushed by a chandelier whose cord had broken. Alas! her child, safe from danger, was desperately calling out to her... [...] Several women were stripped of their jewels; some criminals, having scaled the wall which stands between the garden and the street, acted in complete safety, thanks to the general confusion.

In a few moments the salon of Madame Regnault de Saint-Jean d'Angely [1] was filled with the wounded. It was at the same time terrifying and bizarre to see all these people wearing ballgowns and crowns of flowers, whose moans were in such cruel contrast to their adornments.

We spent a great part of the night consoling them and soothing them as much as was in within our power. When daytime came, we had to return home. Household staff and coaches, all had vanished. Those of us who could walk had to find their way home wearing their ballroom attire and white satin shoes. At this early hour, the streets are choked with market gardeners' carts; it seems we were taken for madwomen, and we were subjected to merciless mockery.

However lacking in seriousness the Parisians might be, this catastrophe left on them a deep and vivid impression. It gave rise to comments of all kinds; some claimed it to be the result of evil political machinations. What is certain is that some overzealous courtiers had urged the Emperor to withdraw before the crowd had blocked all the exits, trying as they were to instil an abhorrent suspicion in his mind; but, calm as always in the presence of danger, Napoleon did not give credence to these petty insinuations; after sending the Empress home in a carriage he returned to the embassy, telling the Prince of Schwarzemberg that he had come to help him put out the fire.

These words had a profound effect on the Austrians and gave rise to deep feelings of admiration and gratitude. All Germanic individuals in attendance at the celebrations, the ambassador first among them, surrounded the Emperor, and in this particular moment this entourage of inimical souls was worth a detachment of the Imperial Guard.

[1] Madame Regnault de Saint-Jean d’Angely, a celebrated beauty of her time, was the wife of Michel-Louis Regnault de Saint-Jean d’Angely, a prominent political figure in Revolutionary and Napoleonic times and a minister in Napoleon’s cabinet. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michel-Louis-%C3%89tienne_Regnaud_de_Saint-Jean_d%27Ang%C3%A9ly

This passage of Countess Potocka’s memoirs, as well as the one about Pauline Bonaparte’s wedding fête, are to be found here:

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5463019n/f259.item, pp. 214-223

This tragedy did not stop the building of unsafe wooden structures into which large crowds of visitors were expected. In 1897 a horrific fire at a charity bazaar, also in Paris, resulted in the death of 126 persons. Many of those were as socially prominent as the Princess of Schwarzenberg, but most of them were just ordinary visitors:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bazar_de_la_Charit%C3%A9

#countess potocka#napoleon#empress marie-louise#marriage of napoleon and marie-louise#prince schwarzenberg#deadly fire

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Acte I. 1er tableau. DEVANT LE TEMPLE D'INDRA, À LAHORE par Jean Emile Daran

Set designs from Le Roi de Lahore, 1877

Acte I. 2e tableau. LE SANCTUAIRE D'INDRA, DANS LE TEMPLE par Auguste Rubé et Philippe Chaperon

Acte II. LE DÉSERT DE THÔL par Jean-Louis Cheret

Acte III. LE PARADIS D'INDRA par Jean-Baptiste Lavastre

Acte IV. UNE GRANDE PLACE À LAHORE par Antoine Lavastre et Eugène Carpezat

Acte V. 1er tableau. LE SANCTUAIRE D'INDRA, DANS LE TEMPLE par Auguste Rubé et Philippe Chaperon

Acte V. 2e tableau. LE PARADIS par Auguste Rubé et Philippe Chaperon

“Sur l'effet final de l'ensemble, la nuit s'illumine. Le sanctuaire s'ouvre au fond. Vision peu à peu lumineuse du paradis, avec Indra, les dieux, les bienheureux assemblés. Alim et Sitâ, faiblissant peu à peu, tombent à genoux, toujours embrassés, près de l'autel d'Indra. Scindia les contemple avec une émotion grandissante...”

All images and the entire livret of Le Roi de Lahore can be found at l'Association l'Art Lyrique Français.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thermidor is a four-act dramatic play by the 19th-century French playwright Victorien Sardou. The play is set during the French Revolution and is one of seven Sardou plays set in that period. The plot follows a young actor, Labussière (based on a historical person), who infiltrates the revolutionary Committee of Public Safety and saves its potential victims by destroying their files. This plot is set against the revolt of 27 July 1794 known as the Thermidorian Reaction.

It was first staged on January 24, 1891 at the Comédie-Française with sets and costumes designed by the author, and executed by Eugène Carpezat, Philippe Chaperon, and others. In the next performance, on the 26th, radical Republican members of the audience took offense at Sardou's criticism of Maximilien Robespierre. They became threatening to the point of riot, with noise, confusion, shouted threats to Sardou's life, and police finally called to clear the crowd away. The protesters were led by the socialist newspaper editor Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray and included the deputy Eugène Baudin. The government of President Carnot prohibited the production from all state-funded venues.

imagine getting mad at a play because it was too mean to Robespierre

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Le Petit Chaperon Rouge (Little Red Riding Hood) 1846 Lithograph by Jaques-Eugène Feyen

152 notes

·

View notes