#Ernest Reyer

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

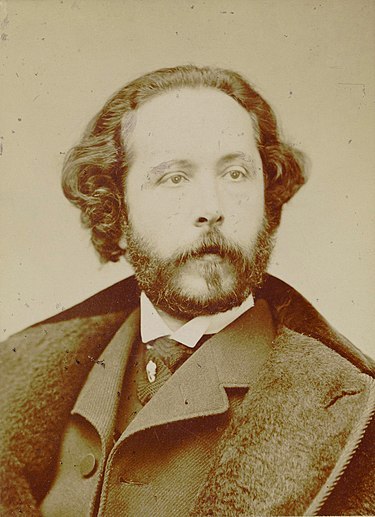

Remembering Ernest Reyer on his birthday:

b. December 1, 1823, Marseille, France

d. January 15, 1909, Le Lavandou, France

Salut! splendeur du jour (Sigurd) · Germaine Lubin

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Ernest Reyer#Reyer#Germaine Lubin#Lubin#Sigurd#dramatic soprano#classical musician#classical musicians#classical voice#classical art#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#music education#music theory#diva#prima donna

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Musique d’ailleurs — Modulation 11 Les Voyageurs de l’Espace

FESTIVAL PROPAGATIONS — dimanche 15 mai 2022

Opéra de Marseille (Foyer Ernest Reyer)

© Pierre Gondard

0 notes

Photo

¿QUÉ OCURRIÓ UN 22 DE ABRIL DE 1892?

Édouard Lalo, violinista y compositor francés, falleció.

Perteneció al movimiento romántico, específicamente a la segunda generación junto a César Frank y Ernest Reyer.

Una de sus obras más célebres, es la “Sinfonía Española” o Symphonie espagnole. Algo que refuerza la duda de su origen español y que transgredía contra el romanticismo nacionalista que había en su país. Puedes escuchar la pieza aquí: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jdf7Zxsa3b8

1 note

·

View note

Text

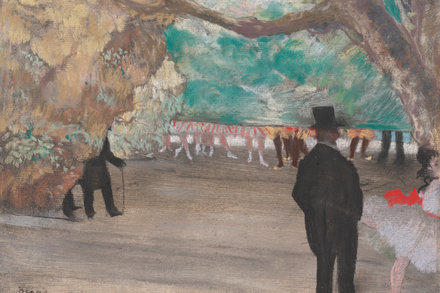

Degas: A Superfan at the Opera, Where Art Tips Into Obsession

BY JASON FARAGO

PARIS — You’ll find them up in the balcony, or in standing room, silently mouthing the libretto or humming along with the score. These are the superfans: the compulsive lovers of opera or ballet or theater who see every performance; who travel from city to city for Marilyn Horne or Mikhail Baryshnikov; who know every downbeat of “Così Fan Tutte” or “A Chorus Line.”

Most are harmless admirers. Some become lay experts. But the superfan can be conniving, as in “All About Eve,” or even murderous: the Tejano sensation Selena was killed by her fan club president. If great art stimulates the heart and the head, the superfan has the ratio out of whack: Passion wins out over reason, and appreciation tips into obsession.

In the annals of French art history, the superfan par excellence is Edgar Degas: the most Parisian of all the Impressionists, and an obsessive of the first magnitude over the opera and ballet. For decades, he watched the leading singers and dancers under the new electric lights, and scrutinized the young members of the corps de ballet in the wings and backstage. Close to half of Degas’s painterly output depicts the Opéra de Paris — which was (and still is) both an opera and a dance company, and which he knew as intimately as Monet knew Giverny’s gardens.

In the year 1885 alone, Degas went 55 times to the still-new Palais Garnier. He saw one opera, the now-forgotten “Sigurd” by Ernest Reyer, at least 37 times. His images of dancers making their grandes arabesques or bending at the barre, now schmaltzy stalwarts of dorm-room posters, were the projects of true mania.

Sign up for the Louder Newsletter

Stay on top of the latest in pop and jazz with reviews, interviews, podcasts and more from The New York Times music critics.

“Degas at the Opéra,” a deep, enlightening, rather perverse exhibition on view here at the Musée d’Orsay through Jan. 19, strips away the sentimentality that has accreted onto Degas’s pictures of dance and music, to reveal the compulsion and single-mindedness that drove their innovations.

It includes more than 200 works in a panoply of media — paintings and pastels, monotypes and painted fans, even solarized photographs of dancers in shocking orange — but only one subject: the hermetic world of Paris music theater, a place of grand spectacle and even grander depravity. The show also features a bronze cast of the tutu-clad “Little Dancer Aged Fourteen,” the only sculpture Degas exhibited in his lifetime; the wax original is in the National Gallery of Art, which will host “Degas at the Opéra” next March. Usually a figure as quaintly perky as Eloise, she has never looked less tender.

It turns out that today’s age of superfandom — wherein the selfie has replaced the autograph, and TV audiences mount petitions against plotlines — has roots in the theatrical milieu of the dawn of industrial capitalism. What Degas demonstrates, and why “Degas at the Opéra” feels so relevant, is that audiences have always held more sway over performers than we admit. Today’s “age of the fan” is not so new, and the opera of 19th-century Paris, in particular, was literally built for adulation and abuse.

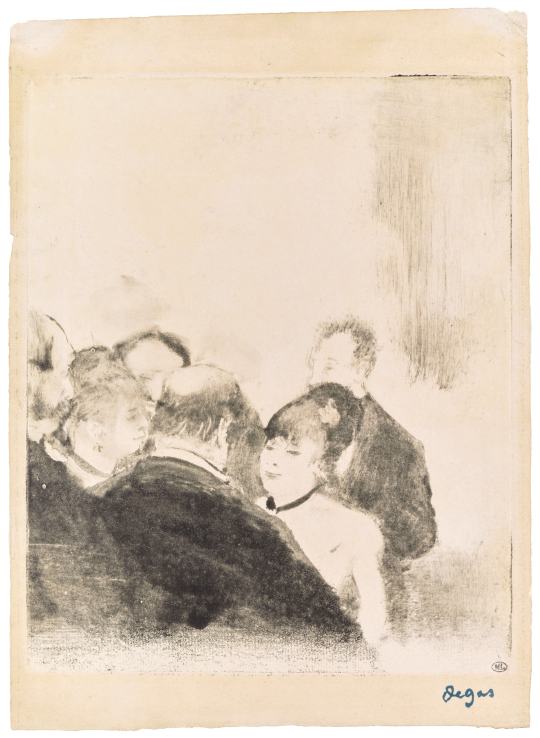

DEGAS CARED FOR MUSIC, and had particular admiration for Gluck, but he was not only at the Opéra to listen. In late 19th-century Paris, opera was a social spectacle that made it an ideal subject for a painter of modern life. For both the upper class and the new bourgeoisie, the real point of a night at the theater was to see and be seen. The performances were often stodgy or familiar — particularly the ballets, which by Degas’s time were little more than a sideshow between opera acts. Not a problem: that allowed the audience to ignore the stage and pay attention to the real theater around them.

Degas went as often as he could afford it: first to the Opéra Le Peletier, the company’s home until a fire destroyed it in 1873, and then to the choke-me-to-death-with-gold-and-marble Garnier, which opened in 1875 and which Degas despised. At both houses, he trained his eye on both the stage and the audience, which he painted from unorthodox perspectives — sometimes a sharp view down from the loges onto the dancers’ heads, sometimes a sotto-in-su gaze up from the orchestra seats to the women in the priciest boxes. In pastel, particularly, he could imitate his view of the backlit performers, their faces lost in the footlights.

Not until 1885 could Degas afford the Opéra’s most expensive subscription, which got him a seat every Monday, Wednesday and Friday — and much better privileges than that. Three-day subscribers, principally aristocrats and financiers who, like today, underwrote new productions, got to enter the Garnier through a dedicated entrance. More important, subscribers had the right to pass through a communicating door backstage, even during performances. Back here, the men would come into the dressing rooms of the divas, and proposition the dancers in the “foyer de la danse,” an opulent mirrored chamber that Garnier designed as, basically, a hunting ground. You had to sign in when you entered: At the Orsay we see Degas’s name on the ledger, day after day.

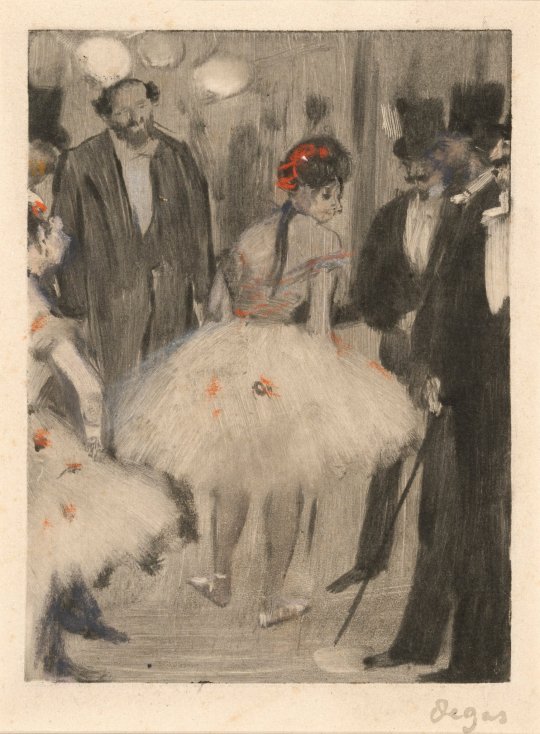

Most of the ballerinas in Degas’s paintings and prints were not the athletic, self-reliant dancers we see on the stage today, but miserable girls from the lower ranks of French society. At midcentury, more than half of the Opéra’s new enrollments werefatherless; their mothers were usually laundresses or concierges, and most girls arrived at the opera house barely fed. There the ballet masters “broke” the girls — stretching their little bodies on racks, reshaping their feet with specially carved boxes. Onstage, or in Degas’s pastels, the girls in their tutus might look angelic. But to the Opéra subscribers these dancers were known as the “petits rats”: little rodents, barely paid, ripe for sexual exploitation.

The distance between the opera and the brothel was vanishingly thin in the late 19th century. For the Romantic author Théophile Gautier, the dancers at the Opéra were “frail creatures offered up in sacrifice to the Parisian Minotaur,” who “each year devours virgins by the hundreds, with no Theseus coming to save them.” In Degas’s images, the most devoted operagoers hover in the wings like birds of prey, and even mothers are on hand to pimp their young daughters to the subscribers.

He made that sordor visible in 80 pitch-dark monotypes he made to illustrate a novella by Ludovic Halévy — his good friend, and the co-librettist of “Carmen.” Degas depicts portly men sitting in the Garnier foyer beside dancers who stare into space, or top-hatted aristocrats swarming around the ballerinas like vultures. (New York audiences saw these prints in the Museum of Modern Art’s “Edgar Degas: A Strange New Beauty” in 2016.)

Yet even in Degas’s now beloved, superficially sunnier pastels, the dancers appear more often like possessions than fellow artists. They are working girls, bent over, tying their slippers, slumped in the corner — rarely elegant, and always being watched. Though he admired some female painters (notably Mary Cassatt), Degas was an intense misogynist, and the formal innovations of his art went together with an avaricious focus on control.

“I have perhaps,” he once confessed, “too often considered woman as an animal.”

LITTLE MARIE VAN GOETHEM, the Belgian-born model for Degas’s statue “Little Dancer Aged Fourteen,” was one of these “petits rats.” She was born in 1865, the second of three girls. Five years later, her father died, and in the same year the Franco-Prussian War broke out. Marie, her sisters, and her laundress-prostitute mother were scrambling across Pigalle. Ballet was the only way out.

At 12, Marie entered the Opéra’s conservatory, and while the dance masters broke her she posed in Degas’s studio for extra money. He sculpted her in fleshy wax at two-thirds life size, her eyes shut tight, her face scrunched up like a wadded rag. Instead of capturing her mid-plié, Degas chose to sculpt her standing in the awkward fourth position, feet perpendicular to the torso and pointing in opposite directions. He gave her a sharp jaw and a forehead like a ski slope. To her body he affixed a real tutu, and real human hair.

If a few avant-garde types appreciated the audacious “Little Dancer” at the Impressionist exhibition of 1881, most of the Paris press despised the sculpture. “Why is she so ugly?” wrote the critic for Le Temps. “Monsieur Degas is doubtless a moralist: Perhaps he knows something about the future of dancers that we do not.” A pretty coy remark — for everyone would have known that dancers were a step away from the bordello, and that their careers, even their next meal, were the gift of well-dressed fans.

Have the performing arts really given up on predation? Today’s dancers might not be as desperate (or as young) as little Marie, but the opera and the ballet have always been games of class distinction, and philanthropy has more uses than a tax write-off. I couldn’t help but think, as I made my second pass of “Degas at the Opéra,” of last year’s scandal at the New York City Ballet, in which the star dancer Chase Finlay exchanged lewd texts with donors to the company, sending pictures of sex acts and pledging to treat female dancers “like the sluts they are.” (Two other fired dancers have since been reinstated.) The Paris Opéra Ballet has its own problems; last year, a leaked questionnaire revealed that three quarters of the dancers reported suffering or witnessing verbal harassment, and one quarter had endured or seen sexual harassment.

Degas never married. He left no record of any mistress. He may have died a virgin. But just because he kept his hands off Marie and the other “petits rats” does not make his art less creepy. Van Gogh, in a letter as blunt as Mr. Finlay’s texts (though tamed in this translation), wrote that Degas “watches human animals stronger than himself getting erections and having sex, and he paints them well, precisely because he doesn’t make such great claims about getting an erection.”

This painter who “didn’t like women,” in van Gogh’s estimation, found at the Opéra an arena of desire and depredation that he could translate into pure form — beautiful and stifling, modern and cold. This is the truth about superfans: they smother what they love.

Degas at the Opéra

Through Jan. 19 at the Musée d’Orsay, Paris; musee-orsay.fr. Opens March 1 at the National Gallery of Art, Washington; nga.gov.

Jason Farago is an art critic for The Times. He reviews exhibitions in New York and abroad, with a focus on global approaches to art history. Previously he edited Even, an art magazine he co-founded. In 2017 he was awarded the inaugural Rabkin Prize for art criticism. @jsf

1 note

·

View note

Text

Brutal

#Ernest Reyer#music#opera#opera tag#French opera#Hector Berlioz#Sigurd#Salammbô#Salammbo#ars longa vita brevis#mortality#immortality#obscurity#the 1800s

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

RECITAL DE BRYAN HYMEL A PARIS

RECITAL DE BRYAN HYMEL A PARIS

Bryan Hymel. Fotografia Dario Acosta

El passat 5 de febrer va tenir lloc a la sala Cortot de Paris un recital del tenor Bryan Hymel el que jo crec que serà el gran tenor dels propers anys, ja que reuneix tot allò que un cantant ha de tenir: veu, tècnica i estil.

No és la primera vegada que Hymel és protagonista d’un apunt a IFL, però és que cada vegada que l’escolto m’agrada més, perquè el seu…

View On WordPress

#Bryan Hymel#Ernest Reyer#Giacomo Meyerbeer#Gioacchino Rossini#Hector Berlioz#Henri Rabaud#Jules Massenet#Morgane Fauchois

1 note

·

View note

Text

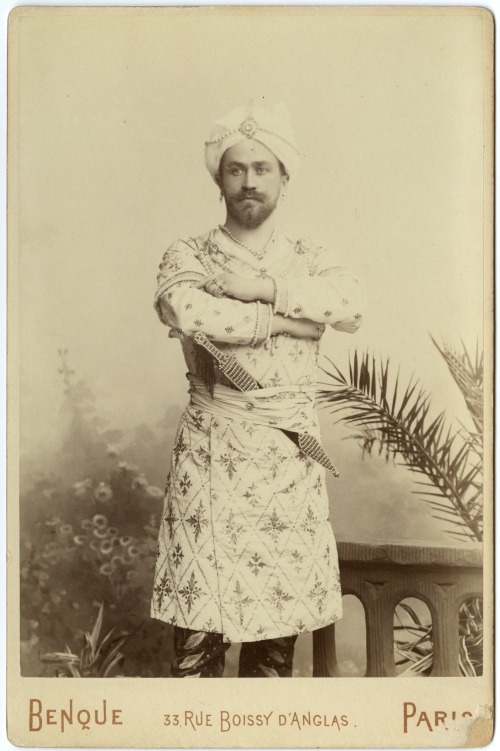

The great French tenor Albert Saléza (1867-1916) as Mathô in Ernest Reyer’s “Salammbô” at the Paris Opéra.

Noted singer, who was born in Bruges, Belgium, and lived there until his twentieth year, when he went to study music at the Paris Conservatory. In 1888 Saleza won the first singing prize and the second opera prize and the same year made his operatic debut, at the Opera Comique, as Mylio in Roi d'Ys. Saleza's voice is a pure and powerful tenor. He has a wide range of parts and is equally as popular in the United States as he is in Europe, having been heard here many times. In 1894 he created the role of Otello in Verdi's opera of that name. He has sung with success the roles of Faust, Rodolphe in La Boheme, Don Jose in Carmen, Jean in Le Prophete, Turridu in Cavalleria Rusticana, and Rhadames in Aida. In Wagnerian opera he has been heard as Siegmund in Die Walkure. His greatest success has been as Romeo in Gounod's Romeo et Juliette. Saleza visited the United States in 1898 and 1899. At Nice he created the role of Eneas in Berlioz's Prise de Troie, and sang the part of Richard in Salvayre's Richard III., also being heard as Matho in the first presentation of Salammbo at Brussels in 1890. Since 1892 he has been engaged at the Paris Opera. He made his first appearance at London’s Covent Garden as Gounod’s Roméo on May 10, 1898, and continued to sing there until 1902; made his Metropolitan Opera debut in N.Y. in the same role on Dec. 2, 1898; was on its roster until 1901, and again in 1904–05; also sang regularly in Paris until 1911, when he joined the faculty of the Cons. He was especially noted for such roles as Gounod’s Faust, John of Leyden, Raoul in Les Huguenots, Edgardo in Lucia di Lammermoor, the Duke of Mantua, Rigoletto, Tannhäuser, Don José, Siegmund, and Otello.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Albert Saléza#tenor#Conservatoire de Paris#Opéra-Comique#Paris Opera#Metropolitan Opera#Met#Covent Garden#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#opera history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

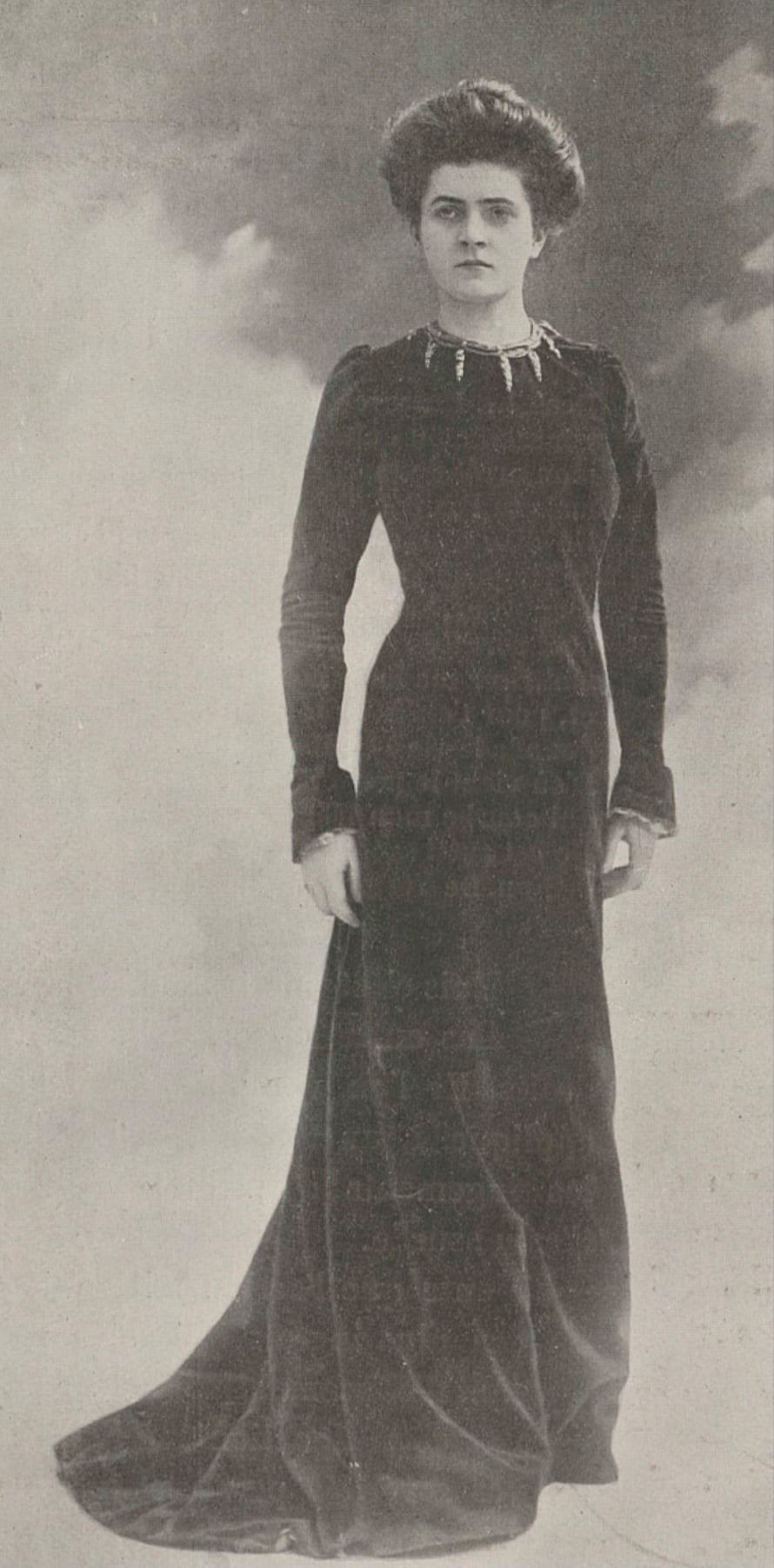

Jeanne Hatto [Marguerite Jeanne Frère] (30 January 1879 – 26 March 1958) was a French operatic soprano. Hatto was born in Saint-Amour-Bellevue in Burgundy in 1879, and studied in Lyon and at the Conservatoire de Paris under Victor Warot. She made her début at the Paris Opéra in 1899. Her repertoire ranged from Rameau to Wagner.

In the New Grove Dictionary of Opera, David Cummings writes of Hatto, "Her powerful voice and commanding stage presence made her a favourite in the dramatic repertory". Among her mainstream roles listed in that article are Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, Sieglinde in Die Walküre, Marguerite in Faust and Donna Elvira in Don Giovanni. In less familiar repertoire she played Telaira in Rameau's Castor et Pollux, and Diana in the same composer's Hippolyte et Aricie and the title role in Ernest Reyer's Salammbô. She created roles in operas by Camille Saint-Saëns (Les barbares, 1901), Xavier Leroux (Astarté, 1901) and Ernest Chausson (Le roi Arthus, 1903).

In 1904 Hatto was the soloist in the first performance of Ravel's song cycle Shéhérazade, and was the dedicatee of the first and longest song of the cycle, "Asie".

#Jeanne Hatto#Opéra de Paris#conservatoire de Paris#Ernest Reyer#Tannhäuser#Richard Wagner#Les Barbares#Camille Saint-Saëns#Iphigénie en Tauride#Christoph Willibald Gluck#Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg#Don Giovanni#Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart#Salammbô#Die Walküre#Der Freischütz#Carl Maria von Weber#Faust#Charles Gounod#Lohengrin#Georges Bizet#La damnation de Faust#Hector Berlioz#Werther#Jules Massenet#Tosca#Giacomo Puccini

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jean Lassalle (Baritone) (Lyon, France 14. 12. 1847 - Paris, France 7. 9. 1909) He was the son of a silk trader. He left Lyon and went to Parisand wanted to become a painter. He studied singing at the Conservatoire National in Parisunder the pedagogue Novelli. He made his debut in 1886 at the Opera House in Lüttich as Saint Bris in ‘’Huguenots’’ of G. Meyerbeer. After his appearances at the opera houses of Lille, Toulouse, Hague and Brussels, he joined in 1872 to the Grand Opéra in Paris, where he made his debut as Wilhelm Tell in G. Rossini’s opera of the same name. Through long years he belonged to the most prominent members of this opera house. Especially he was appreciated at the Covent Garden, where he appeared in the 1879-1881 and 1888-1893 seasons in the parts like the Fliegenden Holländer, Telramund and Hans Sachs. In 1890 he sang at the Paris Opéra-Comique in a gala performance of ‘’Carmen’’ with Jean de Reszke and Nellie Melba. Then in the 1892-1898 (with interruptions) seasons he was a famed member of the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Here he made debut in January, 1892 in as Nelusco in ‘’L'Africaine’’ of G. Meyerbeer. At the Metropolitan Opera his repertoire included Don Giovanni, the title part in ‘’Hamlet’’ of A. Thomas, Valentin in ‘’Faust’’ of C. Gounod, Escamillo in ‘’Carmen’’, Nevers in ‘’Huguenots’’, Telramund, Hans Sachs and Wolfram in ‘’Tannhäuser’’. Then he returned to France and some years appeared in Paris, but since 1901 devoted himself to teaching and received in 1903 a professorship of the Conservatoire de Paris. Jean Lassale counted as one of the most significant Baritons of his epoch, who was compared many times to his predecessor, the famous Jean-Baptiste Faure. His son Robert Lassalle, became a known tenor, who was trained by his father and J. Isnardon.

#Jean Lassalle#Opéra de Paris#conservatoire de Paris#Les Huguenots#Giacomo Meyerbeer#Hamlet#Ambroise Thomas#Guillaume Tell#Gioachino Rossini#L'Africaine#Jules Massenet#Charles Gounod#Samson et Dalila#Camille Saint-Saëns#Ernest Reyer#Covent Garden#Richard Wagner#Don Giovanni#Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart#Damnation de Faust#Hector Berlioz#Metropolitan Opera#Carmen#Georges Bizet#Opéra-Comique

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lucienne Bréval (4 November 1869 in Zürich – 15 August 1935 in Neuilly-sur-Seine) was a Swiss dramatic soprano who had a major international opera career from 1892-1918. Although she appeared throughout Europe and in the United States, Bréval spent most of her career performing with the Paris Opera where she became a greatly admired interpreter of French grand opera roles and Wagner heroines. She also specialized in the works of Gluck and Rameau, becoming particularly associated with the title roles in Gluck’s Armide and Rameau's Hippolyte et Aricie. A favorite of the composers of her day, such as Massenet and Dukas, Bréval sang in numerous world premières during her career. Born with the name Bertha Agnès Lisette Schilling, Bréval initially studied to be a pianist at Lausanne and briefly in Geneva before deciding to pursue an opera career She studied voice with Victor Warot at the Paris Conservatoire before making her debut at the Paris Opera in 1892 as Selika in l'Africaine by Giacomo Meyerbeer. Bréval became a principal soprano at the Paris Opéra and remained there until 1919. Her roles with the company included several world premières including Augusta Holmès's La Montagne Noire (1895), Camille Erlanger's Le fils de l' étoile (1904), Dukas’ Ariane et Barbe-bleue (1907), Massenet's Bacchus (1909), and the title roles in Massenet's Ariane (1906) and Henry Février’s Monna Vanna (1909). She also was Kundry in France's first performance of Wagner's Parsifal (1914). Her other notable roles at the Paris Opera included Brünnhilde in Richard Wagner's Die Walküre (1893), Venus in Wagner's Tannhäuser (1895), Marguerite in Hector Berlioz's La damnation de Faust (1897), and the title role in Rameau's Hippolyte et Aricie (1908). Bréval also occasionally appeared in productions at the Opéra-Comique in Paris. Most notably she portrayed the title role in the world premiere of Massenet’s Grisélidis in 1901, and in 1910 she sang Lady Macbeth in the première of Ernst Bloch’s Macbeth, which he dedicated to her.In 1899, Bréval made her first appearance at the Royal Opera, Covent Garden as Valentine in Meyerbeer's Les Huguenots. Two years later she made her American début at the Metropolitan Opera as Chimène in Le Cid, singing also in Die Walküre and the American première of Ernest Reyer’s Salammbô. Five years later she returned to Covent Garden for the second and last time in the title role of Gluck’s Armide. In 1913 she created the title role in Fauré’s Pénélope at the Opéra de Monte-Carlo; her other title roles there had been in Isidore De Lara's Amy Robsart and in Bizet's Carmen. Throughout her career Bréval appeared in recitals and concerts throughout Europe, including performances in Italy, England, Germany, Holland, Belgium, Switzerland and throughout France. In spite of her great reputation in Europe she was not as well received in America as critics believed her singing lacked polish and described her acting as "semaphoric". After her retirement from the stage in 1919, Bréval taught singing in Paris. The only sound recording of Bréval singing was made on a Mapleson cylinder during a performance of L’Africaine at the Metropolitan Opera.

4 notes

·

View notes

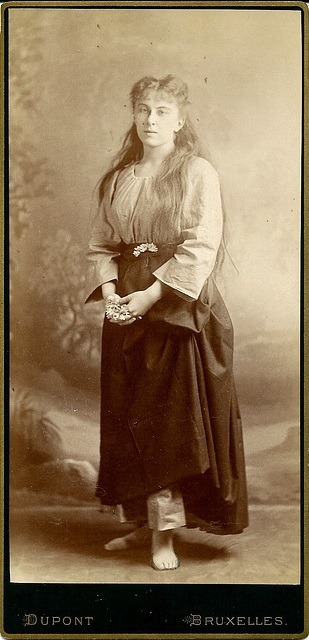

Photo

Blanche Deschamps-Jéhin (also Marie Blanche Deschamps-Jehin) (18 September 1857, Lyons- June 1923, Paris) was a French operatic contralto who had a prolific career in France from 1879-1905. She possessed a rich-toned and flexible voice that had a wide vocal range. She sang in numerous world premieres throughout her career, most notably originating the title role in Jules Massenet’s Hérodiade in 1881. Deschamps-Jehin studied singing in Lyons and Paris before making her professional opera début in 1879 in the title role of Ambroise Thomas's Mignon at La Monnaie in Brussels. She continued to sing at that opera house for the next several years, notably portraying the title role in the world premiere of Jules Massenet’s Hérodiade in 1881 and Uta in the world premiere of Ernest Reyer’s Sigurd in 1884. Deschamps-Jehin joined the roster at the Opéra-Comique in Paris in the mid-1880s, singing there for more than a decade. While there she notably portrayed Margared in the world premiere of Edouard Lalo's Le roi d'Ys (1888), Madame de la Haltière in the world premiere of Massenet’s Cendrillon (1899) and the Mother in the world premiere of Gustave Charpentier's Louise (1900). She also occasionally performed at the Opéra de Monte-Carlo where she sang the title role in the first performance of César Franck’s Hulda (1894) and created the Baroness in the world premiere of Massenet’s Chérubin (1905). In 1891 she made her first appearance at the Paris Opéra as Léonor in Gaetano Donizetti's La favorite, later singing Fidès in Giacomo Meyerbeer's Le prophète, Amneris in Verdi's Aida, Hedwige in Rossini's William Tell, Delilah in Camille Saint-Saëns's Samson et Dalila, Gertrude in Ambroise Thomas's Hamlet, Ortrud, Fricka, and Véronique in the first performance of Alfred Bruneau’s Messidor (1897). Her repertory also included Carmen, Azucena, Brangäne and Erda.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Albert Saléza (18 October 1867 – 26 November 1916) was a French tenor. Saléza, who had hitherto received only a basic education, made rapid progress in all fields: instruction, diction, singing, music... so much so that he won the First prize of the school in 1886, which allowed him to integrate the Conservatoire de Paris where he won again the first prize in singing and the second prize in opera before a jury composed notably of Léo Delibes and Ambroise Thomas. On leaving the conservatory, because of his fragile health, he chose the Opéra-Comique instead of the Opera which would have been too demanding so quickly. From his first role, Mylio in Le roi d'Ys, his performance aroused the enthusiasm of the audience at the Salle Favart. From the Opéra-Comique, Albert Saléza moved on to the Opéra de Nice where he recovered his strength. He gained further notoriety by interpreting Faust, Roméo et Juliette, Carmen, Richard III... In 1892, Ernest Reyer noticed him and offered him the consecration by giving him a role tailored to his needs at the Paris Opera: Matho in Salammbô. The triumph he obtained allowed him to repeat success after success: Le Cid, Die Walküre, la Damnation de Faust His fame was so great that Verdi offered him the role of Otello that he performeded 35 times until May 1895. Unfortunately, health problems hit his vocal chords and forced him to stop for 2 years. In 1897, Saléza returned to the Opéra de Paris, then, in Monte Carlo, Brussels and Covent Garden of London where he sang in particular in Carmen with Emma Calvé, and Roméo et Juliette with Nellie Melba, and very often in front of the future king Edward VII. He reached the pinnacle of his glory in Chicago and the Metropolitan of New York, thanks to his interpretations in Faust, Lucia di Lammermoor, Les Huguenots… In 1912, after all these successes abroad, he returned to France and was appointed professor of lyric declamation at the Conservatoire where his results turned out to be excellent with students who won all the first prizes. But on 26 November 1916, this new career came to a sudden halt when he collapsed during a mass in the église Saint-Charles-de-Monceau. He died on 26 November 1916 in the 17th arrondissement of Paris.

0 notes

Photo

Jean Lassalle (1847 - 1909), baritone. He was the son of a silk trader. He left Lyon and went to Paris and wanted to become a painter. He studied singing at the Conservatoire National in Paris under the pedagogue Novelli. He made his debut in 1886 at the Opera House in Lüttich as Saint Bris in ‘’Huguenots’’ of G. Meyerbeer. After his appearances at the opera houses of Lille, Toulouse, Hague and Brussels, he joined in 1872 to the Grand Opéra in Paris, where he made his debut as Wilhelm Tell in G. Rossini’s opera of the same name. Through long years he belonged to the most prominent members of this opera house. Especially he was appreciated at the Covent Garden, where he appeared in the 1879-1881 and 1888-1893 seasons in the parts like the Fliegenden Holländer, Telramund and Hans Sachs. At the Covent Garden in London he appeared in the following opera premieres: 1881 ‘’Demon’’ (English première) A. Rubinstein 1892 ‘’The Light of Asia’’ Isidore De Lara 1893 ‘’Amy Robsart’’ Isidore De Lara At the Grand Opéra in Paris he appeared in the following opera premieres: 27.4.1877 ’’Le Roi de Lahore’’ Jules Massenet 7.10.1878 ‘’Polyeucte’’ Charles Gounod 1.4.1881 ‘’Le Tribut de Zamora’’ Charles Gounod 14.4.1882 ‘’Françoise de Rimini’’ Ambroise Thomas 21.3.1890 ‘’Ascanio’’ Camille Saint-Saëns 5.3.1883 ‘’Henri VIII’’ Camille Saint-Saëns 1892 ‘’Samson et Dalila’’ Camille Saint-Saëns At the Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels he appeared in the following opera premiere: 15.7.1884 ‘’Sigurd’’ Ernest Reyer In 1890 he sang at the Paris Opéra-Comique in a gala performance of ‘’Carmen’’ with Jean de Reszke and Nellie Melba. Then in the 1892-1898 (with interruptions) seasons he was a famed member of the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Here he made debut in January, 1892 in as Nelusco in ‘’L'Africaine’’ of G. Meyerbeer. At the Metropolitan Opera his repertoire included Don Giovanni, the title part in ‘’Hamlet’’ of A. Thomas, Valentin in ‘’Faust’’ of C. Gounod, Escamillo in ‘’Carmen’’, Nevers in ‘’Huguenots’’, Telramund, Hans Sachs and Wolfram in ‘’Tannhäuser’’. Then he returned to France and some years appeared in Paris, but since 1901 devoted himself to teaching and received in 1903 a professorship of the Conservatoire de Paris. Jean Lassale counted as one of the most significant Baritons of his epoch, who was compared many times to his predecessor, the famous Jean-Baptiste Faure. His son Robert Lassalle, became a known tenor, who was trained by his father and J. Isnardon. Chronology of some appearances (Opera premieres) London Covent Garden 1881 ‘’Demon’’ (English première) A. Rubinstein 1892 ‘’The Light of Asia’’ Isidore De Lara 1893 ‘’Amy Robsart’’ Isidore De Lara Paris Grand Opéra 27.4.1877 ’’Le Roi de Lahore’’ Jules Massenet 7.10.1878 ‘’Polyeucte’’ Charles Gounod 1.4.1881 ‘’Le Tribut de Zamora’’ Charles Gounod 14.4.1882 ‘’Françoise de Rimini’’ Ambroise Thomas 21.3.1890 ‘’Ascanio’’ Camille Saint-Saëns 5.3.1883 ‘’Henri VIII’’ Camille Saint-Saëns 1892 ‘’Samson et Dalila’’ Camille Saint-Saëns Brussels Théâtre de la Monnaie 15.7.1884 ‘’Sigurd’’ Ernest Reyer

0 notes

Photo

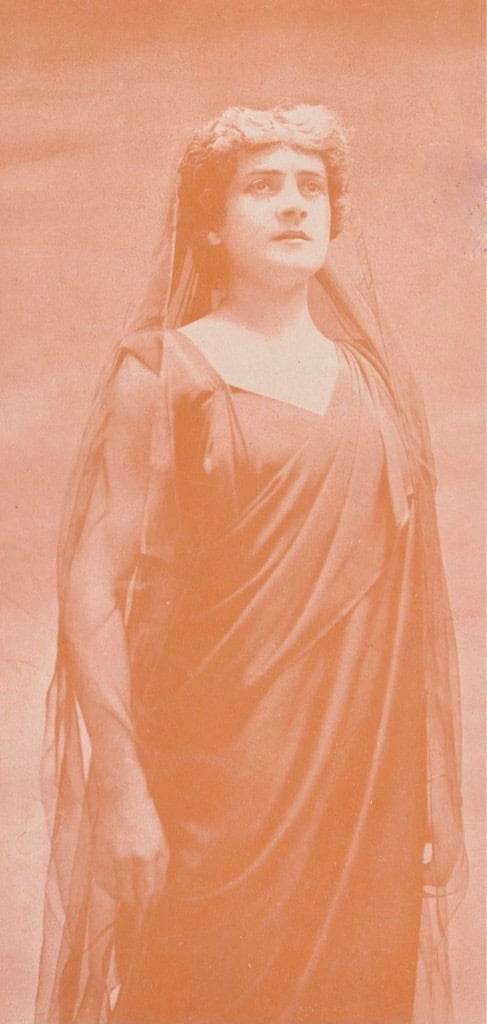

Rose Caron (17 November 1857 – 9 April 1930) was a French operatic soprano.

Caron was born in 17 November 1857 at Monnerville and studied at the Paris Conservatoire, but was not taken on at the Paris Opera; her husband, an accompanist, encouraged her to take lessons from Marie Sasse who helped her to get engagements at the opera in Brussels (having made her concert debut in 1880).

Her first operatic appearance in Brussels was as Alice in Meyerbeer's Robert le Diable, followed by Salomé in Massenet's Hérodiade and Marguerite in Gounod's Faust; noticed by Ernest Reyer, he chose her to create the role of Brunehild in Sigurd in 1884 (and the Paris premiere in 1885). The title roles in Benjamin Godard's Jocelyn (1888) and Reyer's Salammbo (1890) and were also created by Caron in Brussels.

In 1885 she began singing at the Paris Opera, where she became the chief rival of Lucienne Bréval. Caron was the first in Paris to sing Desdemona in Verdi's Otello. Her repertoire included several Wagnerian roles, including Sieglinde in Die Walküre, as well as Rachel in Halévy's La Juive and Valentine in Meyerbeer's Les Huguenots. At the Opéra-Comique she sang Léonore in Beethoven's Fidelio (in 1898) and the title roles in Gluck's Iphigénie en Tauride and Orphée.

Caron sang in the first performance of Debussy's L'enfant prodigue on 27 July 1884, as part of the composition competition of the Prix de Rome in Paris.

Caron sang a few times with the Société des Concerts du Conservatoire: in December 1885/January 1886, she performed airs from Der Freischütz by Weber and La vestale by Spontini; at the official concert of the Exposition Universelle on 20 June 1889, fragments from Ambroise Thomas's Psyché and excerpts from Reyer's Sigurd; and in March 1895, scenes from Gluck's Alceste.

She also sang Marguerite in the stage premiere of Berlioz's La damnation de Faust at Monte Carlo in 1893

After 1895, she reduced her public appearances considerably and concentrated on teaching at the Paris Conservatoire (1904–09) and then as a private tutor. One of her pupils was soprano Alice Zeppilli. She left a few recordings dating from 1903 and 1904, for French Fonotipia, that were recorded poorly, and show her past her prime.

1 note

·

View note

Text

LICEU: la darrera incorporació a la TOSCA 2014, ANDREA CARÈ

LICEU: la darrera incorporació a la TOSCA 2014, ANDREA CARÈ

Andrea Carè

Tal i com ens informava Raúl en un comentari que ens va deixar ahir i segons informa el web del Liceu, el tenor italià Andrea Carè cantarà el rol de Cavaradossi en les funcions del dia 19 i 22 de març, és a dir les dues darreres del tercer repartiment, al costat de Fiorenza Cedolins i Vittorio Vitelli, les dues primers les cantarà José Ferrero (avui i el dia 15), ja que Riccardo…

View On WordPress

#Andrea Carè#Anna Caterina Antonacci#Anton Eriksson#Emma Vetter#Ernest Reyer#Frédéric Chaslin#Géraldine Chauvet#Giacomo Puccini#Giuseppe Verdi#John Erik Eleby#Marianne Hellgren Staykov#Norma#Sigurd#Susanne Resmark#Tosca#Un Ballo in Maschera#Vincenzo Bellini

0 notes