#Emily LaBarge

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Emily LaBarge, from her essay The Schedule of Loss, as featured in Granta Magazine

#i.#emily labarge#the schedule of loss#words#essays#typography#...#the body as a haunted house#hauntings#on violence

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Following Yoko Ono’s Anarchic Instructions

A major retrospective at Tate Modern instructs visitors to draw their own shadows, shake hands through a canvas and imagine paintings in their heads.

Yoko Ono with her piece, “Half-A-Room” at Lisson Gallery in London in 1967. A new retrospective of Ono’s work at Tate Modern takes viewer through her body of work chronologically, including her performances, installations, films, text, sounds and sculptures. Credit… Clay Perry

By Emily LaBarge

The critic Emily LaBarge saw the show in London.

Published Feb. 15, 2024Updated Feb. 22, 2024

In December 1971, a man at the exit of the Museum of Modern Art had a question for departing visitors: “What did you think of the Yoko Ono exhibition?”

Some were confused (“What exhibition?”), others irritated (“I couldn’t find it!”) or delighted (“Well I just thought it was amazing”). To a man who had trouble locating the show, the interviewer conceded, “It’s here, it’s just mostly in people’s minds.”

The man nodded. “Yes,” he said, “I thought that might be the case.”

These were some of the reactions to Ono’s “Museum of Modern (F)art,” a self-appointed MoMA debut, staged without the museum’s permission. She published a catalog, placed ads in The Village Voice and inserted a sign at the museum entrance stating that hundreds of perfume-soaked flies had been released inside. It was up to visitors to find them, the notice said, perhaps by following the errant wafts of fragrance drifting past the Pollocks, Picassos or Van Goghs.

More than 50 years later, the Tokyo-born artist known for her marriage to John Lennon as much as her avant-garde (and often very funny) art has a much-anticipated retrospective at Tate Modern in London, running through Sept. 1. The show, “Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind,” contains more than 200 works spanning seven decades. Like “Museum of Modern (F)art,” which is part of the retrospective, most of those works are in people’s minds.

The exhibition takes us through Ono’s work and life chronologically. The first space immediately establishes the sense of spare elegance that dominates the artist’s oeuvre, which unfolds across performance, installation, film, text, sound and sculpture.

“Add Colour (Refugee Boat)" at the MAXXI Foundation in 2016. Credit… Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

Employees at the Tate Modern drawing a new version of the piece on Tuesday. Credit... Daniel Leal/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

Like many of the works in the show, “Lighting Piece” is presented in multiple iterations. It is one of her earliest “instruction pieces”: a small typewritten card, dated “autumn 1955,” and affixed to the wall. It reads, “Light a match and watch till it goes out.”

Nearby, three photographs show Ono doing just that, while sitting at a grand piano onstage, in 1962. Projected on another wall is a 1966 filmed version of the same instruction. We see the flickering flame, shot with a high-speed camera and then played back at a standard speed, waning at an impossibly slow rate. It exists across time and space and you, too, are invited to watch it die today, tomorrow, whenever.

Born in 1933, Ono grew up in wartime and postwar Japan. It might be easy to link the austerity of her work to a childhood marked by scarcity, homelessness and mass destruction. “Those experiences of the early days cast a long shadow in my life,” the artist has said, recalling how she and her brother, displaced and hungry in the Japanese countryside, would look up at the sky and imagine menus filled with delicious meals that they could not eat.

Perhaps this epicurean fantasy was one Ono’s first instruction pieces, but from early on, her work was also shaped by a sophisticated educational background: She was the first female philosophy student at Gakushuin University in Tokyo, then studied poetry and musical composition at Sarah Lawrence after she moved to New York in 1953.

“Grapefruit, Page 11” from “SECRET PIECE” (1964). Credit... via Yoko Ono

Ono quickly fell in with the city’s most admired experimental musicians and performance artists of the time, including John Cage, La Monte Young and George Maciunas — the father of the Fluxus movement, which emphasized how art could be made by anyone and happen anywhere.

In the retrospective, the decade after her arrival in New York is largely represented by documentation of performances in loft spaces and galleries, and later onstage, also in Tokyo, where she returned from 1962-64.

Two “Instruction Paintings” are examples of interactive works from 1961, in which the title tells us what to do. “Painting to Be Stepped On,” for example, is just what it sounds like — a geometric cutout of canvas stuck to the floor — and shows Ono’s embrace of the idea that art is live rather than static and relies on audience participation. This is encouraged throughout the exhibition, which invites visitors to follow various instructions: draw your shadow, shake hands through a hole in a canvas, imagine a painting in your head.

In no work is this more striking and unsettling than in “Cut Piece” (1964), one of the most powerful performance pieces of the 20th century. In a 1965 version, filmed at Carnegie Hall by the Maysles brothers, Ono kneels onstage in her best suit and invites audience members to cut away pieces of her clothes.

While some are modest in their takings, the same man approaches twice — once cutting a hole in her shirt so that her breast pokes through, and later gleefully removing the top half of her slip and cutting the straps of her brassiere beneath. Ono sits motionless and passive — though a few vague eye rolls provide relief — while the audience takes what it wants from her without protest.

Ono performing “Cut Piece” at Carnegie Hall in New York in 1965. Credit... Minoru Niizuma

The following year, Ono traveled to London and the rest, as they say, is history. Performances gave way to sculptural installations of white chess sets, rooms of objects cut in two, apples on transparent plinths and mirrored boxes that reflect the smile of whomever opens them.

“Film No. 4 (‘BOTTOMS’)” (1966-67) is a veritable who’s who of London’s alternative art scene via their naked derrières in motion. The simple film seems silly, but is also mesmerizing and anarchic: “an aimless petition signed by people with their anuses,” according to Ono. (It was banned by the British Board of Film Censors.)

Ono met Lennon at one of her openings. It was the beginning of an artistic collaboration frequently dismissed as pop celebrity high jinks or derided in sexist and racist terms. (No, Ono was not an interloper who destroyed the Beatles, etc.)

Later work sits uneasily between high and low registers, conceptual installation and mainstream media intervention. (In 1982, she placed an ad in The New York Times calling for peace.) The evocative koan-like poetry of her earlier scores — “watch the sun until it becomes square,” “give moving announcement each time you die” — becomes simplistic statements: “Take a piece of the sky. Know that we are all part of each other,” “IMAGINE PEACE,” “PEACE is POWER.”

At the end of the exhibition you are invited to write a wish on a white card and affix it to a potted olive tree. Is wishing enough? Can we imagine peace? At first I was cynically uneasy about the lack of “art” in later text works. But Ono’s instructions are not as straightforward as they seem, and they require some faith in other people. What did I think of the Yoko Ono exhibition? What did you think?

“Apple” (1966) Credit… Daniel Leal/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Vulnerability of Tracey Emin

A visit to the celebrated artist in Margate, ahead of a major exhibition at White Cube, London, reveals a painter in her prime, creating strikingly raw canvases

BY Emily LaBarge in Profiles | 25 SEP 24

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alice Neel

Alice Neel Mother and Child, Havana (1926)

Alice Neel was born in January 1900 and grew up in a conservative town in rural Pennsylvania. She ‘couldn’t stand Anglo-Saxons’, she later said, ‘their soda-cracker lives and their inhibitions’. In 1921, she quit her job as a secretary for the US air force and enrolled at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women. She was influenced by the work of the American painter Robert Henri, who had founded the Ashcan School – a movement that championed gritty depictions of urban scenes. ‘I didn’t want to be taught Impressionism,’ Neel explained. ‘I didn’t see life as Picnic on the Grass. I wasn’t happy like Renoir.’ Her latest retrospective, Alice Neel: Every Person is a New Universe, at the Munch Museum in Oslo (until 26 November), brings together 59 of Neel’s paintings and drawings from across six decades.

In 1925, she married Carlos Enríquez, an artist from a wealthy Cuban family. The couple spent a year in Havana and the work Neel produced there shows Henri’s continuing influence. She painted the people she saw on the streets, though she disliked the term ‘portraits’ (too bourgeois) and preferred to call her paintings ‘pictures of people’. Mother and Child, Havana (1926) is filled with movement, the thick, muscular brushstrokes affording a special clarity to the face of the little girl in a pink dress, who sits on her mother’s lap. (London Review of Books https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v45/n19/emily-labarge/at-the-munch-museum?utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=20230930icymiUS&utm_content=20230930icymiUS+CID_ce7884eebb5d3e8279bd1b8171e6f54d&utm_source=LRB%20email&utm_term=Alice%20Neel%20at%20the%20Munch%20Museum

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Turner, Monet, Berisot

Volcanic ash from Mount Tambora’s eruption, as well as coal pollution, gave Turner glowing atmospheres to paint in his day. So did the toxic air enveloping the city of London which Monet responded to in some of his paintings a century later. A recent article by Emily LaBarge in The Times treats of the two artists. Here’s one of several Monets reproduced in the article: Monet’s “Charing Cross…

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Antonio Velardo shares: What Is Photography? (No Need to Answer That.) by Emily LaBarge

By Emily LaBarge Two exhibitions by Japanese artists raise deep questions about the medium, and — refreshingly — leave them hanging. Published: November 21, 2023 at 09:18AM from NYT Arts https://ift.tt/aD5l1iV via IFTTT

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Megan Rooney | Thaddaeus Ropac

An enigmatic storyteller, Megan Rooney works across a variety of media – including painting, sculpture, installation, performance and language – to develop interwoven narratives. The body in her work, as both the subjective starting point and final site for the sedimentation of experiences explored through her practice. The subjects of her works are drawn directly from her own life and surroundings, while her references are deeply invested in the present moment. She addresses the myriad effects of politics and social conventions that manifest in the home and on the female body. Recurring characters and motifs form part of a dreamlike narrative that is never fixed, but obliquely references some of the most urgent issues of our time. Painting on uniform canvases measuring 200 x 150 cm – the wingspan of the average woman – Rooney presents layers of ethereal forms, often sanded back and painted over multiple times to create abstracted narratives without a discernible beginning or end. 'Each painting is a capsule of time and space,' writes critic Emily LaBarge, 'a palimpsest of effort and care, a portal into an intimate conversation between artist and canvas in which the journey of the work remains pulsing just beneath its surface.' She punctuates these layers with a contrasting dash of colour or energetic line, drawing the viewer in, only to disrupt their gaze with unexpected elements. These elements are often suggestive of corporeal forms that emerge and recede from view in an otherworldly space, as if captured in the process of becoming.

(via Megan Rooney | Thaddaeus Ropac)

0 notes

Text

Emily LaBarge, from her essay The Schedule of Loss, as featured in Granta Magazine

#too immaterial for the rituals of mourning we have available..... scream.#emily labarge#the schedule of loss#noli me tangere#words#essays#typography#the great wound#on memory#!!!!#the body as a haunted house

903 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Writing programme at the Royal College of Art is pleased to announce a two-day conference on 'AUTO—', featuring keynote speaker Anne Boyer.

'Autofiction is like a dream; a dream is not life, a book is not life,' wrote Serge Doubrovsky in his 1977 novel, Fils, which is often cited as the origin of the term 'autofiction'. Recent years have seen Doubrovksy invoked time and again to address a new writerly preoccupation with a seemingly old genre. Some trace autofiction back to Joyce or Proust, to the Confessions of Rousseau, and Augustine before him, or even further, to Hesiod’s Works and Days. 'How ‘Auto’ is ‘Autofiction?' asks a recent article; and 'Drawn from life: why have novelists stopped making things up?'

But what is at stake in these contemporary conversations, and what are the conditions that have produced them? What is the balance between the 'auto' (autobiography, memoir, and 'the self' in general) and the 'fiction'? Is the distinction between fact and fiction, the truth and the fabricated? Or is there, increasingly, a desire to redistribute the relation between the self and fiction: the question of how to live or how to create as reflexively embedded within the process of making itself? Autofiction as a term — a practice, a concern, a process — remains mobile and in flux, perhaps telling us more about what we want from a work of art than its sometimes plainly stated aims and origins. So just what is it that makes today’s autofiction so different, so appealing?

This two-day conference aims to generate a critical and creative discourse around ideas, practices, theories, contradictions, arguments, refutations, histories — and more! — of the AUTO— as it relates to creative works. We hope to wrangle with and refine its usage, which can sometimes seem catch-all; and we will also consider the ways in which these conversations relate and spill into other genres and disciplines.

Keynote speaker: Anne Boyer

Other speakers include: Heike Geissler, Claire-Louise Bennett, Juliet Jacques, Brian Dillon, and many more.

‘AUTO—’ is organised by Emily LaBarge and the Writing faculty – Brian Dillon, Jeremy Millar and Sally O’Reilly.

Get tickets and more info here.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seeing Things | Granta

Seeing Things

Emily LaBarge

‘The City of the city is jagged and spiky, tangled, twisted – burned down, paved over, rebuilt, unruly with wealth and poverty side by side, as they have always been.’

Genet writes of Rembrandt’s paintings as works that stun and transfix, because they strive for the depersonalised and so universal – ‘when he prunes objects of all identifiable characteristics . . . he gives them the most weight, the greatest reality.’

0 notes

Photo

Emily LaBarge wrote the most careful and correct and least ‘explainy’ explanation of Durga’s Too Much and Not the Mood for the Los Angeles Review of Books.

177 notes

·

View notes

Text

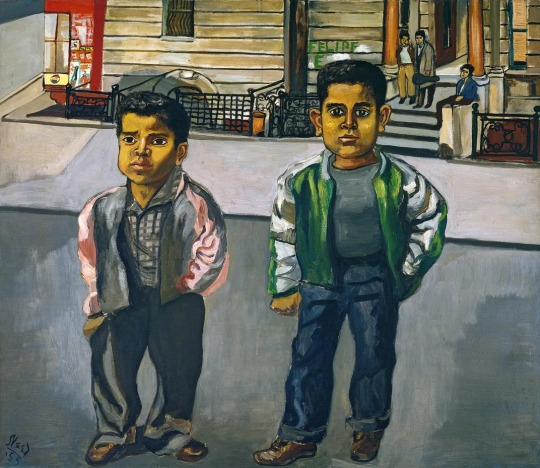

Alice Neel, Jackie Curtis and Ritta Redd, 1970

Alice Neel, Dominican Boys on 108th Street, 1955

Neel encouraged her sitters to ‘assume their most characteristic pose, which in a way involves all their character and social standing – what the world has done to them and their retaliation’. But she was also keen to emphasise the formal qualities of her work: ‘You see, I’m not just a simple figure painter. The abstract elements and the geometric layout of the canvas are very important to me.’ Her art is most radical for its non-dogmatic, non-prescriptive character. Despite the evidence of what the world ‘has done’ to her sitters, her portraits are never mawkish. London Review of Books https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v45/n19/emily-labarge/at-the-munch-museum?utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=20230930icymiUS&utm_content=20230930icymiUS+CID_ce7884eebb5d3e8279bd1b8171e6f54d&utm_source=LRB%20email&utm_term=Read%20more

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Antonio Velardo shares: In This Exhibition, Gender Meets Climate Activism. It’s a Lot. by Emily LaBarge

By Emily LaBarge A sprawling show at the Barbican Art Gallery in London presents works under the banner of “ecofeminism,” linking women’s oppression with humanity’s destruction of nature. Published: October 18, 2023 at 04:25AM from NYT Arts https://ift.tt/HgRlpoi via IFTTT

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Emily LaBarge, from her essay The Schedule of Loss, as featured in Granta Magazine

780 notes

·

View notes