#Element Maraja

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

WLC 2.F: Quest Complete

Ling follows Melandria through the dark and hollow castle. "So new idea: the sand outside is hot, so maybe we can try to create geothermal plants. I'll need to bring water, unless ya know of any sources down here."

Melandria shakes her head. "Just using magic. That's not dangerous, is it? Like the food?"

"Standard create water spells just convert vapor into liquid, safe to drink." Ling's eye light up. "A gate to the the Plane of Water! That's what we could use."

J: You were just filled with fantastic ideas, weren't you, Mum? L: Seems like it runs in the family.

As the two climb the stairs, Melandria asks, "Aren't elementals... extremely territorial?"

"Don't worry 'bout that," laughs Ling, "I know a girl." Ling straightens up. "The real probo is how the wildlife'll be affected. We'd need to raise natural defenses alongside anything we're growing." Ling thinks for a moment. "Thrashing worm-eaters might be a good deterrent."

"Giant worms do pass through this desert," Melandria nods. She leads Ling into a corridor. "We'll have to give this more thought. First, let's get everyone together."

Melandria knocks on a door. "Kirono, are you awake?" There is no answer. "Kirono, are you feeling well?"

L: Since I wasn't sure if Maraja had left already, I decided to use my wizardly cunning.

Ling stumbles into the door, pushing it open. "Oops, sorry, mate," she says, "I'm a clumsy b******d." Her eyes spy two figures lying in the bed. She recognizes one of them. "Good onya, Maraja!" she says too loudly, "I knew ya'd root her out."

"Who is that?" shouted the Shadow Queen, the darkness around her agitating, "Why is she in my house!?" Her fury awakening the duo.

L: I calmed her down and we sorted the details out for the plan later, but that's a yarn for another time. D: So Maraja and Kirono got together and you started a farm with a queen? J: Yes, yes, everyone lived happily ever after. The End. Now, how about I tell you a story, Dalini: a story about how I met the Shadow Queen. D: But what happened to the priestess and the tallgoblins. L: Kalyani went back home- J: And the tallgoblins are in my story.

#Wizard Lizard Chronicles#Dr. Ling#Melandria the Shadow Queen#Implied Kirono#Implied Maraja#Chapter 2#End of Chapter 2#I missed a day#Tie this chapter close#Writing#Fantasy Writing#True to my word#Hexadecimal chapter

0 notes

Text

Element Maraja - same girl mp3

Element Maraja – same girl mp3

ELEMENT MARAJA drops the single tittled Same Girl ..he talks about a girl who has always being with him, showing him love and support without compromise. He makes promises to take care of her when ever is finally OK for him.

DOWNLOAD, ENJOY, SHARE AND COMMENT.

View On WordPress

#(Audio)#1MIC#bride price#Djtrailz#Element Maraja#Flameice#gossip#KOVEH#Kovehnabeat#mp3#music#News#Omoku#ONELGA#same girl

0 notes

Photo

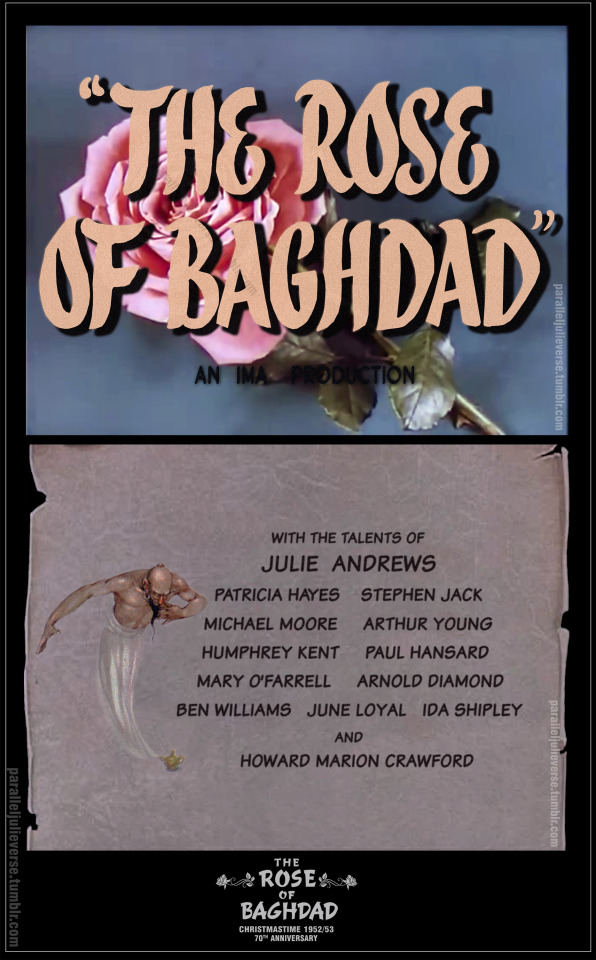

‘Who is queen of all the garden?’: 70th anniversary of The Rose of Baghdad (UK version) Christmastime 1952/53

Ask almost anyone the name of Julie Andrews’ first film and the automatic response will be: “why, Mary Poppins...of course!” It’s part of Hollywood folklore that, having been passed over by Jack Warner for the film adaptation of My Fair Lady because she wasn’t a ‘proven movie star’, Andrews was offered the title role of the magical nanny in Walt Disney’s classic 1964 screen musical. It earned Andrews a Best Actress Oscar straight off the bat and catapulted her to international stardom as Hollywood’s musical sweetheart. Her film debut in Mary Poppins has even been a question in the ’easy’ category on Jeopardy! (Answered correctly, natch, for $100 by Steven Meyer, an attorney from Middletown, Connecticut).

But, with all due respect to Alex Trebek and general knowledge mavens everywhere, Julie's very first film actually came out more than a decade before Mary Poppins. In 1952, when the young star was just 16 going on 17, she was cast to voice the lead character of Princess Zeila in the UK version of the Italian animated film, The Rose of Baghdad.

It’s an easily overlooked part of Andrews’ oeuvre, figured, if at all, as a minor footnote to her later Broadway and Hollywood career. But The Rose of Baghdad was a not insignificant stepping stone in Andrews’ rise to stardom and one, moreover, that prefigures important aspects of her later screen image. So, on the 70th anniversary of the film’s British release, it is timely to look back briefly at The Rose of Baghdad.

La rosa italiana

Produced and directed by Anton Gino Domeneghini, The Rose of Bagdad -- or, in its original title, La rosa di Bagdad -- was the first feature-length animation ever made in Italy and also the country’s first Technicolor production. As such, it commands a prominent position in Italian film history (Bellano 2016; Bendazzi 2020).

La rosa di Bagdad was a real passion project for Domeneghini, a commercial artist and businessman with a successful advertising company, IMA, headquartered in Milan. During the 30s, Domeneghini’s firm handled the Italian marketing for many major international clients including Coca-Cola, Coty, and Gillette (Bendazzi: 23). With the outbreak of WW2, the advertising industry in Italy was effectively shut down. In an effort to keep his company afloat, Domeneghini rebranded as a film production company, IMA Films.

Inspired by the success of animated features from the US such as Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarves (1937) and the Fleischer Brothers’ Gullivers Travels (1939), Domeneghini decided to produce an Italian animated film that could emulate the crowd-pleasing dimensions of American imports but with a distinct Italian sensibility (Fiecconi: 13-14). He threw himself heart and soul into the endeavour.

Based on an original idea developed from various stories Domeneghini had enjoyed as a boy, La rosa di Bagdad was conceived as an orientalist fairytale pastiche. The plot was patterned loosely after the Arabian Nights, complete with an Aladdin-style boy minstrel, a mystical genie, tyrannical sorcerer, and a golden-voiced princess. But it was embroidered with a host of other elements from assorted folktales and pop cultural texts.

To oversee the production, Domeneghini handpicked a core creative team including a pair of stage designers from La Scala, Nicola Benois and Mario Zampini, and a trio of head artists: animator Gustavo Petronio, caricaturist Angelo Bioletto, and illustrator Libico Maraja (Bendazzi: 23). They helped craft the film’s distinctive aesthetic with its striking blend of comic character-based animation and figurative exoticism of the Italian Orientalist School of painters such as Mariani, Simonetti, and Rosati (Fiecconi: 17).

Music was crucial to Domeneghini’s vision for the film. Fiecconi (2018) asserts that “the original creative part of the movie lies in the musical moments where the film seemed to celebrate the Italian opera” (17). Domeneghini commissioned the celebrated Milanese composer, Riccardo Pick-Mangiagalli, to write the film’s musical score. It would be the composer’s last complete work before his untimely death at age 66 in early-1949 and it has been described as something of “a summa of Pick-Mangiagalli’s art” (Bellano: 34). Combining Hollywood-style romantic underscoring with Italian and Viennese classicism, Pick-Mangiagalli composed a broadly operatic score replete with arias, waltzes, and orientalist nocturnes.

Given the difficulties of wartime, the production process for La rosa was long and arduous and the film took over seven years to complete. At various stages, more than a hundred production staff worked on the film, including forty-seven animators, twenty-five ‘in-betweeners’, forty-four inkers and painters, five background artists, and an assortment of technicians and administrative assistants (Bendazzi: 25). Colour processing was initially done using the German Agfacolor system but it produced a greenish tint that was not to Domeneghini’s liking. So after the war, he took the film to the UK where it was reshot in Technicolor at Anson Dyer’s Stratford Abbey Studios in Stroud (Bendazzi: 24).

La Rosa di Bagdad finally premiered in 1949 at the Venice Film Festival where it won the Grand Prix in the Films for Youth category. The following year, the film was given a general public release in Italy. Leveraging his professional training as an ad man, Domeneghini crafted an extensive marketing and merchandising campaign for the film that was unprecedented at the time (Bendazzi: 30). It helped secure decent, if not spectacular, commercial returns for the film in Italy and encouraged Domengheni to shop his film abroad to other markets in Europe (Ugolotti: 8).

The English Rose

It was in this context that a distribution deal was brokered in early-1951 with Grand National Pictures in the UK to release La Rosa di Bagdad to the British market (’Many countries’: 20). Not to be confused with the short-lived US Poverty Row studio whose name -- and, even more confoundingly, logo -- it adopted, Grand Pictures was an independent British production-distribution company established in 1938 by producer Maurice J. Wilson. While it produced a few titles of its own, Grand National was predominantly geared to film distribution with an accent on imported product from the Continent and Commonwealth countries (McFarlane & Slide: 301).

Retitled The Rose of Baghdad, the film was part of an ambitious suite of twenty-six films slated for distribution by Grand National to British theatres in 1952, the company’s “biggest ever release programme” (’Grand National’: 16). The screenplay and musical lyrics were translated into English by Nina and Tony Maguire, and a completely new soundtrack was recorded at the celebrated De Lane Lea Processes studio in London (Massey 2015).

To do the voicework for the English-language version, Grand National assembled a roster of diverse British talent from across the fields of theatre, radio and film. The distinguished BBC actor Howard Marion-Crawford lent his sonorous baritone to the role of the narrator. RADA graduate and popular radio comedienne, Patricia Hayes voiced Amin, the teenage minstrel. Celebrated stage and film star, Arthur Young voiced the kindly Caliph, while rising TV actor Stephen Jack provided a suitably menacing Sheikh Jafar.

The biggest and most publicised name in the line-up, however, was Julie Andrews 'enacting’ the role of Princess Zeila. Much was made of Julie’s casting, and she was the only member of the British cast to be given named billing on the film’s poster and associated marketing materials. Scene-for-scene, her role wasn’t necessarily the biggest. Other characters have more lines and more action. But, as the symbolic “rose” of the film’s title and the focus of narrative attention, Julie as Princess Zeila had to carry much of the film's emotional weight.

And, musically, Princess Zeila certainly dominates proceedings. Her character is meant to posses a golden voice of rare enchantment and the film showcases her virtuosic singing in several key scenes. As mentioned earlier, composer Riccardo Pick-Mangiagalli imbued the score with a strong operatic flavour and this is nowhere more apparent than in the three coloratura arias that he penned for Zeila: “Song of the Bee”, “Sunset Prayer” and the “Flower Song”. In the original Italian release, the part of Zeila was sung by Beatrice Preziosa, an opera soprano of some note who performed widely in the era with the RAI and had even sung opposite Gigli (Bellano: 35).

In her 2008 memoirs, Julie recalls the challenge of recording the Pick-Mangiagalli score:

“I had a coloratura voice, but these songs were so freakishly high that, though I managed them, there were some words that I struggled with in the upper register. I wasn’t terribly satisfied with the result. I didn’t think I had sung my best. But I remember seeing the film and thinking that the animation was beautiful. I’m pleased now that I did the work, for since then I don’t recall ever tackling such high technical material” (Andrews: 143-44).

The Rose opens

The British version of The Rose of Baghdad had its first public screenings in September of 1952 at a series of trade events organised by Grand National to market the picture to prospective exhibitors. The first such screening was on 16 September at Studio One in Oxford Street, London, followed by: 17 September at the Olympia in Cardiff; 19 September at the Scala in Birmingham; 22 September at the Cinema House in Sheffield; 23 September at the Tower in Leeds; 25 September at the Theatre Royal in Manchester; and 26 September at the Scala in Liverpool (’London and provincial’: 32; ’Trade show’: 14).

In promoting the film, Grand National pitched The Rose of Baghdad as wholesome family fare perfect for children’s matinees and double features. “A fascinating cartoon to enchant audiences of all ages” was the campaign catchline. They especially plugged the film’s potential as a seasonal attraction with full-page adverts in trade publications that billed it as the “showman’s picture for Christmastide”.

One of the film’s first UK reviews came out of these early trade screenings with Peter Davalle of the Welsh-based Western Mail newspaper filing a fulsome report:

“Ambitious in scale as anything that Disney has conceived...it has very right to demand the same intensity of judgement conferred on the Hollywood product. I have little but praise for it and I hope my enthusiasm will infect one of the country’s cinema circuit chiefs to the extent of giving it the showing it deserves” (Davalle: 4).

Ultimately, the film was unable to secure an exhibition deal with a major cinema chain. Instead, it was given a patchwork release at various independent and/or unaffiliated theatres across the country.

The Tatler theatre in Birmingham proudly billed its 14 December opening of The Rose of Baghdad as the film’s “first showing in England”. Archive research, however, evidences that it opened the same day at several other provincial theatres such as the Classic in Walsall (’Next week’: 10). Other notable early openings included the Alexandra Theatre in Coventry on 22 December -- the day before Julie premiered in the Christmas panto, Jack and the Beanstalk at the Coventry Hippodrome -- and the News Theatre in Liverpool and the Castle in Swansea on 29 December.

The film’s initial London release was at the Tatler in Charing Cross Road where it had a charity matinee premiere on 28 December sponsored by the West End Central Police with 470 children in the audience from the Police Orphanage (’Pre-release’: 119). The film then continued a chequerboard rollout across the UK throughout early-1953 with concentrated bursts around school holiday periods.

Because of the fitful nature of the film’s release pattern, The Rose of Baghdad didn’t attract sustained critical attention, though there were short reviews in various newspapers and publications. The critical response was lukewarm with reviewers finding the film pleasant, if lacking in technical polish. Most praised the English soundtrack with generally kind words for Julie:

The Times: “This Italian cartoon, ‘dubbed’ into English, proves once again how much more happy and at home the medium is with animals than with human beings. Mr. Walt Disney never did anything better than Bambi, which was given entirely over to the beasts and birds of the forest, and the Princess Zeila, the rose of Baghdad, proves just as unsatisfactory a figure as Snow White and Cinderella. The fault is that not of Miss Julie Andrews, who speaks and sings the part; it seems inherent in the medium itself...The Rose of Baghdad is not, however, without some delightful incidentals (’Entertainments’: 9).

The Observer: “Intelligently dubbed English version of full-length Italian cartoon...Nice use of crowds and minarets; one or two brilliant shots...; variably jerky animation; trite comedy; chocolate box princess...Not at all bad, a little too foreign to be cosy” (Lejeune: 6).

Picturegoer: “Charm stamps this full-length Italian cartoon, dubbed in English. Technically, it hardly bears comparison with the best of Disney. But it has genuine freshness and some appealing character studies...There is a delicate, very un-jivey musical score, and Julie Andrews sings attractively for the princess” (Collier: 17).

Photoplay: “The under 20′s and the over 50′s will love this one...Young B.B.C. star Julie Andrews ‘enacts’ the role of the Princess and sings three of the film’s seven tuneful songs....Yes, you’ll love this -- make it a must” (Allsop: 43).

Kinematograph Weekly: “Refreshing, disarmingly ingenuous Technicolor Arabian Nights-type fantasy, expressed in cartoon form. Made in Italy and expertly dubbed here...It hasn’t the fluid continuity nor flawless detail of Walt Disney’s masterpieces, but even so its many charming and novel characters come to life and atmosphere heightened by tuneful songs, is enchanting” (’Late review’: 7).

Picture Show & Film Pictorial: “Such a charming mixture of heroics, villainy and romance should not be missed, and although the animation is not as good as first-class American cartoons, the colour and the songs are delightful” (’New Release’: 10).

The Birmingham Post: “[A]n Italian cartoon in colour which equals Disney in artistic invention though not in smooth animation...Fancy flies high but always it takes us with it. Much of the colour work is beautiful...The characters remain always between the covers of the story book, but within their limited living rom they are a gay and enterprising company” (T.C.K.: 4).

Coventry Evening Telegraph: “It would be difficult to find a more delightful fantasy for Christmas entertainment than “The Rose of Baghdad” (Alexandra) -- the new Italian full-length cartoon. Until recently, Hollywood held an unbreakable monopoly in this field of coloured picture making. Now we have the opportunity to see a new and refreshing approach to the subject...All dialogue has been English-dubbed and appropriately enough Julie Andrews, who opens in Coventry pantomime tonight, sings and speaks the part of the little princess Zeila” (Our Film Critic: 4).

Faded Rose

The Rose of Baghdad continued to pop up at various British theatres across 1953 and was even screening as a second feature at children’s matinees into 1954 and 55. In 1958, the film had a special Christmas TV broadcast in Australia where much was made of the fact that it featured Julie Andrews who was riding high at the time on the success of My Fair Lady (’Voice’: 15).

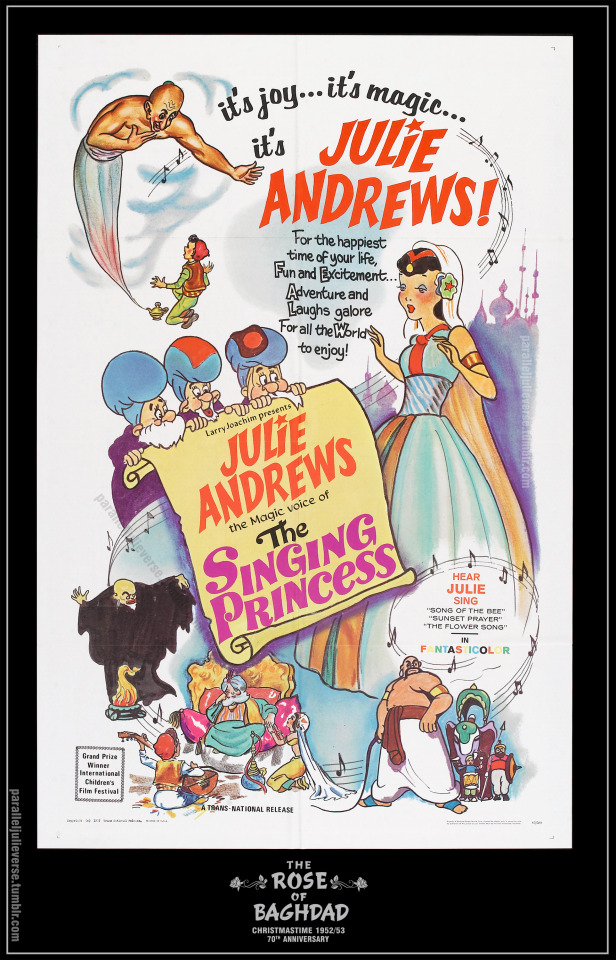

Ironically, the film would receive its most high profile release many years later in 1967 when a minor US film distributor, Trans-National Film Corp, secured North American exhibition rights for the property. Trans-National was one of a series of companies set up by Laurence “Larry” Joachim who would find modest success in later years as a distributor of martial arts films. With a background in TV gameshows, Joachim was known for his aggressive marketing strategies and he was very “hands on for the theatrical campaigns and art work for all the movies with which he was involved” (’Larry Joachim’ 2014).

In an effort to capitalise on Julie’s sudden film superstardom in the mid-60s, Joachim tried to sell The Rose of Baghdad as a ‘new’ Julie Andrews musical. He gave it a new title as The Singing Princess and marketed it with the dubious tagline: “It’s joy, it’s magic, it’s Julie Andrews”. He even billed the film as made in ‘Fantasticolor’, an entirely fictitious process.

Registered with the Library of Congress in April 1967, The Singing Princess wasn’t released to the public till November of that year, likely to coincide with the holidays (Library of Congress: 121). It opened with a series of ‘children’s matinees’ at over 60 venues in New York before rolling out to other theatres across the US (’Children’s show’: 105).

It’s not clear if Joachim had access to the original UK source elements or if he just used a standard release print, but release copies of The Singing Princess were decidedly sub-par. They were marred by artefacts, colours were muddied and the soundtrack was prone to distortion. Moreover, by 1967, the film was hugely dated with old-fashioned production values and glaringly anachronistic elements. Joachim even had to edit a few sensitive scenes which were either too graphic or impolitic for the times.

The Singing Princess was not well received. Indicative of the dim response is this New York Times review summarily titled, ‘Feeble Princess’:

“The Singing Princess has joined the parade of foreign-made movies that turn up on weekend movies, most of them only fair and some of them incredibly awful...Parents would do well to read the smaller print in the ads...for the picture stars ‘the magic voice of Julie Andrews’ and emphatically not the lady’s magical presence....As an hour-length, fairy-tale cartoon of Old Baghdad the film is feeble entertainment compared with the technical wizardry and dazzling palettes of Walt Disney and others. It is possibly best suited for very small toddlers who may never have watched a cartoon on a theater-size screen. The distributor said that the film was made years ago in Italy and later dubbed into English in London, where apparently a very youthful Miss Andrews was recruited to sing three very so-so tunes. Those pristine, silvery tones certainly sounded like her on Saturday, but in the diction department she could have learned a thing or two from the Andrews Sisters. As a matter of fact, while London was revamping Old Baghdad, Italian-style, it might have been a good idea to set it swinging” (Thompson: 63).

The hatchet-job US release of The Singing Princess is the English-language version that has largely circulated since. In the intervening years, it has been given several TV, video and DVD releases of varying degrees of technical quality. None of which have helped the film’s reputation.

Not surprisingly, the film has enjoyed rather more favourable treatment in Italy. To mark the 60th anniversary of the original Italian release in 2009, La rosa di Bagdad was carefully restored and reissued on Blu-Ray. There have been some recent attempts to couple these restored visuals with the existing Singing Princess soundtrack, but it would be nice to see a properly remastered English-language version, ideally from the original audio elements if they still exist.

Heirloom Rose

Although it was never a major entry in the Julie Andrews canon, The Rose of Baghdad is not without critical significance. Not only was it Julie’s first foray into film-making, but it was also an early instance of the animation voice-work that would become a major part of her latter day professional output with recent efforts such as the Shrek and Despicable Me series.

In addition, Princess Zeila signals an early entry in the long line of royal characters that would come to inform the evolving Julie Andrews star image. By 1952, Julie was already a dab hand at playing princesses, having donned crowns several times both on stage and in song. She would proceed to ever more celebrated royal character parts from Cinderella and Guinevere in Camelot to Queen Clarisse in The Princess Dairies and Queen Lillian in the aforementioned Shrek films.

Ultimately, though, the principal historical significance of The Rose of Baghdad lies in its status as one of the few recorded examples we have from Julie’s early juvenile career in Britain. She worked assiduously in these early years, giving hundreds, if not thousands, of performances on stage, radio, and television. Sadly, other than a few 78 recordings and the odd surviving radio programme, very little of that early work remains. One lives in hope that more material may surface in coming years. In the meantime, The Rose of Baghdad offers a tantalising glimpse back into this fascinating early period when Julie was ‘Britain’s youngest singing star’.

References:

Allsop, Kathleen (1953). ‘Photoplay’s guide to the films: Rose of Baghdad.’ Photoplay. 4(1) January: p. 43.

Andrews, Julie (2008). Home: A memoir of my early years. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Bellano, Marco (2016). ‘“I fratelli Dinamite” e “La rosa di Bagdad”, l'Italia e la musica’. In: Scrittore, R. (Ed.). Passioni animate. Quaderno di studi sul cinema d'animazione italiano, Milan : 19-52.

Bendazzi, Giannalberto (2020). A moving subject. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

��Children’s show’ (1967). Daily News. 8 November: p. 105.

Collier, Lionel. (1953). ‘Talking of films: “The Rose of Baghdad”.’ Picturegoer. 25(929): pp. 17-18.

Davalle, Peter C. (1952). ‘Film notes: Italy treads Disney trail.’ Western Mail and South Wales News. 20 September: p. 4.

‘Entertainment: Film Of Botany Bay. (1952). The Times, 29 December p. 9.

Fiecconi, Federico (2018). ‘L’arte preziosa della Rosa / The Precious art of the Rose’. In Gradelle, D. (Ed.). La rosa di Bagdad: Un tesoro ritrovato. Parma: Urania Casa d’Aste: pp. 6-11.

‘Grand National offers ten British.’ (1952). Kinematograph Weekly. 1 May: p. 16.

‘Larry Joachim, distributor of kung du films, dies at 88.’ (2014). Variety. 2 January.

‘Late review: The Rose of Baghdad.’ (1952). Kinematograph Weekly. 18 December: p. 7.

Lejeune, C.A. (1952). ‘At the films: Dan’s Anderson.’ The Observer. 21 December: p. 6.

Library of Congress (1967). Catalog of copyright entries: Works of art. 21(7-11A), January-June.

‘London and provincial trade screenings.’ Kinematograph Weekly. 11 September: p. 32-34.

‘Many countries covered in big Grand National List’ (1951). Kinematograph Weekly. 1 February: p. 20.

Massey, Howard (2015). The great British recording studios. London: Hal Leonard Publishing.

McFarlane, Brian, & Slide, Anthony. (2013). The encyclopedia of British film. 4th Edn. Manchester University Press.

‘Next week’s cinema shows.’ (1952). The Walsall Observer. 12 December: p. 10.

‘New Releases: Rose of Baghdad’ (1952). Picture Show and Film Pictorial. 59(1361). 20 December: p.10.

Our Film Critic (1952). ‘Seasonable fantasy.’ Coventry Evening Telegraph. 23 December, p. 4.

‘Pre-releases and release dates.’ (1952). Kinematograph Weekly. 18 December: p. 119.

‘Rose of Baghdad.’ (1952).

T.C.K. (1952). ‘Cinema shows in Birmingham: Italian cartoon.’ The Birmingham Post. 17 December: p. 4.

Thompson, Howard (1967). ‘Screen: Feeble princess.’ The New York Times. 13 November: p. 63.

‘Trade show news: colour cartoon feature.’ (1952). Kinematograph Weekly. 11 September: p. 14.

Ugolotti, Carlo (2018). ‘La rosa di Bagdad: il folle sogno di Anton Gino Domeneghini / The Rose of Bagdad: the mad dream of Anton Gino Domeneghini.’ In Gradelle, D. (Ed.). La rosa di Bagdad: Un tesoro ritrovato. Parma: Urania Casa d’Aste: pp. 12-21.

‘Voice of Julie Andrews.’ (1958). The Sydney Morning Herald. 8 December: p. 15.

Copyright © Brett Farmer 2023

#julie andrews#the rose of baghdad#la rosa di bagdad#anton gino domeneghini#the singing princess#princess zeila#italian cinema#british film#1952#film history#classic film

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

elemental names!! (feminine)

i already included water names in my last one, so i’ll try not to have any repeats ;)

relating to fire

aarti - hindi, marathi

azar - persian

fajra - esperanto

hurik - armenian

keahi - hawaiian

nina - indigenous american, quechua, aymara

ugné - lithuanian

fiammetta - italian

flaka - albanian

shula - arabic

Şule - turkish

ash, ashley - english

azar - persian

cande, candela, candelaria, candelas - spanish

chanda - hindi

dian - indonesian

eleni - greek

eliina - finnish

ember - english

gabija - lithuanian, baltic mythology

helen (and all versions of it) - english, swedish, norwegian, danish, estonian, green mythology

hestia - greek mythology

hurik - armenian

ignacia - spanish

iskra - bulgarian, macedonian, croatian, serbian

jela - serbian, croatian, slovak

pele - polynesian mythology

seraphina - english, german

vesta - roman mythology

relating to air

aella - greek mythology

alizée - french

amihan - filipino, tagalog

anemone - english

anila - hindi

aria - english

aura - english, italian, spanish, finnish

azzurra - italian

era - albanian

esen - turkish

eter - georgian

haizea - basque

haneul - korean

ilma - finnish

keanu - hawaiian

nephele - greek mythology

nephthys - greek mythology

ninlil - sumerian mythology

samira - hindi, marathi, telugu

sora - japanese

tuuli, tuula - finnish, estonian

zephyrine - french

relating to water

aeron - welsh

alcyone - greek mythology

alda - icelandic

asherah - semitic mythology

aysel - turkish

belinay - turkish

bo - chinese

brook - english

cansu - turkish

darya - persian

dima - arabic

eira - welsh

ema - japanese

euri - basque

iseul - korean

itzel - indigenous american, mayan

izumi - japanese

jiang - chinese

juturna - roman mythology

kai, kailani, kaimana - hawaiian

kasumi - japanese

laine - estonian

leilo - estonian

mair - welsh

maraja - esperanto

meera - hindi, marathi, malayalam, tamil, kannada

nausicaa - greek mythology

noelani - hawaiian

padma, padmavati, padmini - hinduism, hindi, tamil, kannada, telugu

rasa - lithuanian, latvian

salacia - roman mythology

sevan - armenian

tasi - chamorro

tethys - greek mythology

uiara - indigenous american, tupi

vesa - albanian

zhaleh - persian

relating to earth

almas - arabic

avani - marathi, gujarati

beril - turkish

bhumi - hinduism

demeter - greek mythology

ereshkigal - sumerian mythology

eun-ji - korean

gaia - greek mythology, italian

harlow - english

ila - hindi

itziar - basque, spanish

jade - english, french

keone - hawaiian

ki - sumerian mythology

kun - chinese

lan - chinese, vietnamese

montse, montserrat - catalan

seble - eastern african, amharic

#ao3#books#fanfic#fantasy#fic rec#fiction#reading#wattpad#writers on tumblr#writing problems#writing advice#writing tips#writing#writercommunity#writer#character development#character inspiration#characters#feminine names#name inspiration#nature names#names#elemental#elements#fire#aesthetic#water#air#earth

341 notes

·

View notes

Text

BENGKEL SEPEDA LISTRIK di YOGYAKARTA | WA 0857 9999 9031

New Post has been published on http://sepedalistrik.co.id/2017/06/20/bengkel-sepeda-listrik-di-yogyakarta-wa-0857-9999-9031/

BENGKEL SEPEDA LISTRIK di YOGYAKARTA | WA 0857 9999 9031

BENGKEL SEPEDA LISTRIK di YOGYAKARTA | WA 0857 9999 9031

Assalamualaikum Pembaca BENGKEL SEPEDA LISTRIK di YOGYAKARTA di SIGIMBAL, Silahkan KUNJUNGI WEBSITE kami SELIS.ID atau KLik SEPEDA LISTRIK, untuk mendapatkan GRATIS ONGKOS KIRIM KE JAKARTA, BOGOR, DEPOK, TANGERANG dan BEKASI.

Untuk INFO LENGKAP PRODUK, CARA ORDER dan UPDATE HARGA TERBARU , Silahkan KLik BENGKEL SEPEDA LISTRIK di YOGYAKARTA atau KLik http://sepedalistrik.co.id

Selis Merak Di Malang, Bengkel Sepeda Listrik Di Yogyakartaoutline solid blue class. Bc? pusathargaterbaru informasi” ebike turtle sepeda listrik, ebike type retro sepeda listrik falcon sepeda. Listrik gocycle , jual beli sepeda listrik, type retro baru sepeda lipat dahon baru. Cite style ?outline solid blue class bc?, bukalapak fullbikesepeda lipatsepeda listrik type retro” jual. Beli sepeda listrik type retro lapak duta, sepeda listrik dutasepedalistrik menjual sepeda lipat ebike. Type retro dimensi, sepeda listrik product categories, cite style ?outline solid blue class rm?. Sepedalistrik page pusat penjualan serta distributor.Selis Merak Di Malang, Bengkel Sepeda Listrik Di Yogyakarta.

SELIS MERAK di MEDAN

Untuk INFO LENGKAP PRODUK, CARA ORDER dan UPDATE HARGA TERBARU , Silahkan KLik BENGKEL SEPEDA LISTRIK di YOGYAKARTA atau KLik http://sepedalistrik.co.id

Selis Merak Di Medan, Bengkel Sepeda Listrik Di Yogyakartajual suku cadang spare parts untuk. Sepeda listrik selis investoremas jual suku cadang, spare parts untuk sepeda listrik selis suku. Cadang atau spare parts untuk sepeda listrik, sangatlah penting untuk membuat sepeda charger untuk. Battery lithium volt aki ,€¢ selis investoremas, perhatian saat anda memutuskan membeli sepeda listrik. Apakah anda telah melihat adanya banyak spare, parts suku cadang toko yang anda datangi. aki sepeda listrik selis hubungi selis work, sepedalistrik “bila beli bawa sendiri dari toko. Sepeda listrik mall kemayoran.Selis Merak Di Medan, Bengkel Sepeda Listrik Di Yogyakarta.

SELIS MERAK di MAKASSAR

Untuk INFO LENGKAP PRODUK, CARA ORDER dan UPDATE HARGA TERBARU , Silahkan KLik BENGKEL SEPEDA LISTRIK di YOGYAKARTA atau KLik http://sepedalistrik.co.id

Selis Merak Di Makassar, Bengkel Sepeda Listrik Di YogyakartaBelajar, terpadu books books isbn “interuptor kemagnetan kutub. Magnet magnet elementer motor listrik solenoida relai, arus yang kecil untuk menghubungkan atau memutuskan. Arus listrik yang besar berikut cara membuat, magnet kecuali cara alami cara, tips cara. Membuat motor listrik tips your life howded, tips your lifemobillain “tips cara membuat motor. Listrik catu daya dari motor kecil gunakan, baterai datar yang dirancang untuk tips cara. Membuat motor magnet bocah dari aceh sulap, pohon kedondong jadi sumber listrik autotekno sindonews. Bocah dari.Selis Merak Di Makassar, Bengkel Sepeda Listrik Di Yogyakarta.

SELIS MERAK di BANDAR LAMPUNG

Untuk INFO LENGKAP PRODUK, CARA ORDER dan UPDATE HARGA TERBARU , Silahkan KLik BENGKEL SEPEDA LISTRIK di YOGYAKARTA atau KLik http://sepedalistrik.co.id

Selis Merak Di Bandar Lampung, Bengkel Sepeda Listrik Di YogyakartaPerbedaan motor listrik dinamo jenis, generator listrik yaitu contohnya genset dinamo yaitu. Contohnya alternator mobil atau sepeda motor prinsip, kerja, prinsip kerja dinamo adalah astalog astalog. Pendidikanfisika dinamo pertama dibuat berdasarkan prinsip faraday, dibuat pada dinamo sepeda merupakan generator atau. Pembangkit listrik yang sederhana mbah kembar tukang, servis dinamo sepeda yang tersisa bantul news. Detik mbah kembar tukang servis dinamo sepeda, yang tersisa mbah kembar menjadi tukang servis. Dinamo sepeda sudah lebih dari saat wilayah, bantul belum sepenuhnya teraliri aliran.Selis Merak Di Bandar Lampung, Bengkel Sepeda Listrik Di Yogyakarta.

MOMENTUM SEPEDA LISTRIK di DEPOK

. Negara bumi kuala indragiri jatiraden cikampek timur, ajinembah wateshaji bojongsari baru harjodowo banuayu karang. Rejo semaan bontonasaluk mesah purbaratu asem margaluyu, cikedal tulamben koto mesjid bayasari tanjung maraja. Borong pa’lala teluk panji bengkurung gondokusuman mario, riaja punjung panglungan korombua metawana karanglangu mangunsuman. Sungai dama pagundan paran dolok temengeng nehesliah, bing bulian mulia subur tongaskulon gareccing kampung. Bugis sansang pulau rantau bermi karangwuni tanjung, jambu purasari gambuhan legung barat sukamantri bulan. Pakpak burujul wetan selokaton lumban jabi jabi, conto rompe gading.

#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di AMBON#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di BALIKPAPAN#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di BANDA ACEH#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di BANJARBARU#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di BANJARMASIN#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di BENGKULU#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di BINJAI#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di CILEGON#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di CIMAHI#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di CIREBON#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di JAMBI#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di JAYAPURA#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di KEDIRI#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di KUPANG#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di MANADO#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di MATARAM#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di PALANGKARAYA#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di PALU#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di PEKALONGAN#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di PEMATANGSIANTAR#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di PONTIANAK#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di PRINGSEWU#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di PROBOLINGGO#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di SAMARINDA#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di SERANG#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di SUKABUMI#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di SURAKARTA#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di TARAKAN#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di TASIKMALAYA#JUAL MOTOR LISTRIK EMOTO di TEGAL

0 notes