#Ekow Eshun

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Strangers by Ekow Eshun

From Malcolm X to Justin Fashanu, Eshun uses historical figures to illuminate contemporary struggles – and his own alienation

“All blacks in this country are condemned to be performers.” This is the thought, allegedly, of Ira Aldridge, a 19th-century black Shakespearean actor, who features in Ekow Eshun’s The Strangers. Why “allegedly”? Because there’s no record of Aldridge’s assertion. Eshun’s book, though, is not a novel; it’s “creative nonfiction”. This innovative approach, while successful, will nonetheless vex historians who wince at the use of speculation, rather than verifiable fact, in presenting the past.

Toni Morrison argued that black lives are “spoken of and written about as objects of history, not subjects within it”. How then to humanise and investigate the interior lives of historical figures in the absence of source material? It’s a dilemma addressed in Eshun’s hybrid of biography and memoir through an extraordinary feat of empathy. Along with Aldridge, Eshun takes four other black pioneers – Matthew Henson (an explorer), Frantz Fanon (a psychiatrist and thinker), Malcolm X (an activist) and Justin Fashanu (a footballer) – and writes about them using the second person. But he does it so intimately that “you” becomes a proxy for “I”.

In the chapter on Aldridge, his 1830s portrayal of Othello “causes only revulsion” in the mind of audiences who cannot accept “a full-blooded Negro, incarnating the profoundest creation of Shakespeare’s art”. But the actor is not enraged by detractors; his mournful response echoes his reflection on how it feels to play Othello in the light of Desdemona’s betrayal: “You feel only grief. The weight of this man’s story bears down on you.” The contrast between Aldridge’s sensitivity and how he is misperceived by the white British public is pitiable.

It’s surprising to learn that for much of his life Eshun, too, has felt misperceived. In decades past, as a cultural commentator – a favourite on the BBC’s Late Review, editor of Arena magazine and director of the Institute of Contemporary Arts – Eshun seemed to transcend race. But, lately, he has addressed it more directly as curator of exhibitions such as In the Black Fantastic and The Time Is Always Now. He is alive to the way in which every Black man is “heir to [a] legacy of caricature, which renders him simultaneously invisible and hypervisible”. Henson, for example, faithfully accompanies American explorer Robert Peary on a gruelling Arctic expedition, subsequently claimed to be the first to reach the north pole. But not only does Peary refuse to share the glory with his companion, critics such as congressman Robert Macon use Henson to cast doubt on the venture, labelling him a “useful Negro tool” and an untrustworthy witness. “The moral support of a white man,” laments the English reporter Henry Lewis, “would have done much toward establishing an unqualified claim of success.”

Fanon, Malcolm X and Fashanu are more widely known than Aldridge and Henson, but the same canopy of sadness and loneliness veils them, and Eshun captures it in his remarkable, imaginative writing. In 1955, working in sympathy with Algerian rebels in the midst of a brutal colonial war with France, Martinique-born psychiatrist Fanon is “stretched taut with the effort of maintaining a double life”. A decade later, ostracised by the Nation of Islam, Malcolm X catches sight of his mentee, Muhammad Ali in Ghana. The pugilist turns his back: “Watching Muhammad’s car roar away, you know it’s not possible for real love to disappear, even in the heat of betrayal.” Fashanu, threatened with lurid tabloid exposé, reluctantly comes out, becoming Britain’s first openly gay footballer before his suicide in 1998.

Stories from Eshun’s own life provide the thread that links his case studies, and include glimpses of unease over his inchoate racial identity. In one stark moment, he confesses that at the age of nine he took a Brillo pad to his face to rid him of its shameful blackness. There are vignettes of other trailblazers, such as the musician and producer Jay-Z. Eshun praises Jay-Z for his “final disavowal of the shell of unfeeling masculinity” that he has carried through life, in favour of “an open embrace of vulnerability, a reckoning with love as the signal marker of black humanness”. It’s a fitting description of the author, too. Ever since leaving home for university, dumping his past into a black bin liner bound for the incinerator, it seems Eshun has been a stranger to himself. His book is an act of rapprochement rendered with great emotional intelligence and tenderness.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Strangers: Five Extraordinary Black Men and the Worlds That Made Them

By Ekow Eshun.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Strangers : Five Extraordinary Black Men and the Worlds that Made Them by Ekow Eshun

This is an important book. It is important to know and remember how white Europeans have treated other peoples and in particular black people. In the same way that it is important to have books and films about the holocaust because it is all too easy to forget. We must be able to recognise how history is repeating itself and stop it before it is too late.

Man’s inhumanity to man never ceases to amaze and depress me.

However, this book is much more than just that.

The title says it is about five people but there are many more than that that we are introduced to. Of the ‘five’ the only name I was really familiar with was Malcolm X’s but this is a very different man from the one I learnt about through the British contemporary press. The other name I had at least come across was the footballer, Justin Fashanu, but I knew nothing of his (sad) story.

I found this book revealatory not just about the people I had heard of but about historical events I was ignorant of.

Highly recommend.

Courtesy of NetGalley, Penguin UK and Hamish Hamilton.

#Ira Aldridge#matthew henson#frantz fanon#malcolm x#Justin Fashanu#Ghana#books#review#netgalley#racism#hamish hamilton#penguin books#ekow eshun#the strangers#homoseuxality#football#prejudice

0 notes

Text

Some other days...

"Three shadows remembering light" 2023 as part of the group show in and out of time curated by Ekow Eshun, Gallery 1957.

Production assistance from Nicholas Kwame Ansah, Yaw Donkor and Jibril Salifu

Design and Construction with Gershon Gidisu

📸 by yours truly

Featuring

Godfried Donkor

Priscilla kennedy

Zanele Muholi

Yaw Owusu

Lyle Ashtonn Harris

Serge Attukwei Clottey

Gideon Appah

Amoako Boafo

Kwesi Botchway

Tiffane Delune

Timothy Arthur

Todd Gray

Kenturah Davis

Juliann Knxx

Shiraz Bayjoo &

Tunji Adeniyi-Jones

#photography#photochemistry#plant pigments#plant dyes#arborgrams#photograms#eric gyamfi#cyclical times

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

INSPIRATIONS:

ALISHA B WORMSLEY

"project blackness as a site of possibility" - Ekow referencing the Black Fantastic exhibit, where I first saw this work... hmmmm

0 notes

Link

🌟💍👸🕺💃🎥 “The Time is Always Now” puts the Afro-descendant gaze at the heart of modern portraiture From February 22 to May 19, 2024, the National Portrait Gallery in London explores the reappropriation of the “black figure” by the African diaspora in modern portraiture during a moving exhibitio...... 🎶🏆💔📸🎉

0 notes

Text

WOW. Okay, In the the Black Fantastic by Ekow Eshun has to be my favorite book of the year so far. It’s so good!! And I’ve barely started

1 note

·

View note

Text

Artist Inspo

Below are artists that have been initial inspiration for my artworks. After looking into the book in the black fantastic a Catalog by Ekow Eshun, I was drawn to these Artists :

Alisha Wormsley ‘There are Black People in the future’

Ruth Carter Costume designer for Black Panther

Wangechi Mutu ‘The Seated’

Beddo ‘Comic book cover remix’

Lina Iris Viktor ‘Syzygy’

1 note

·

View note

Photo

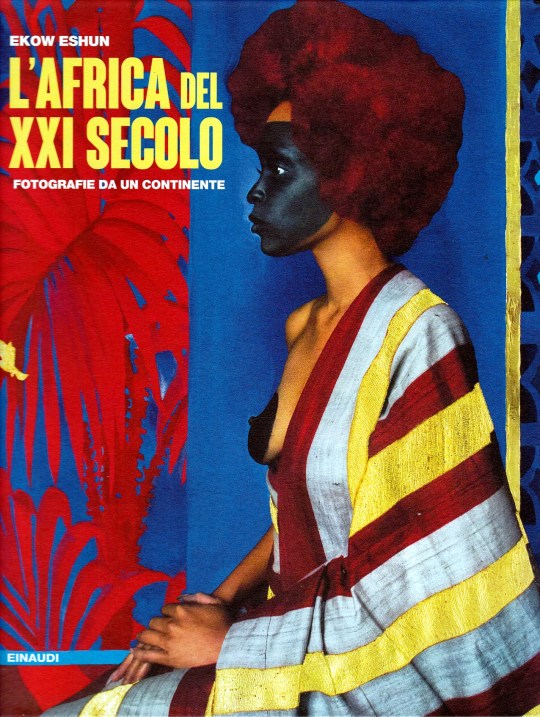

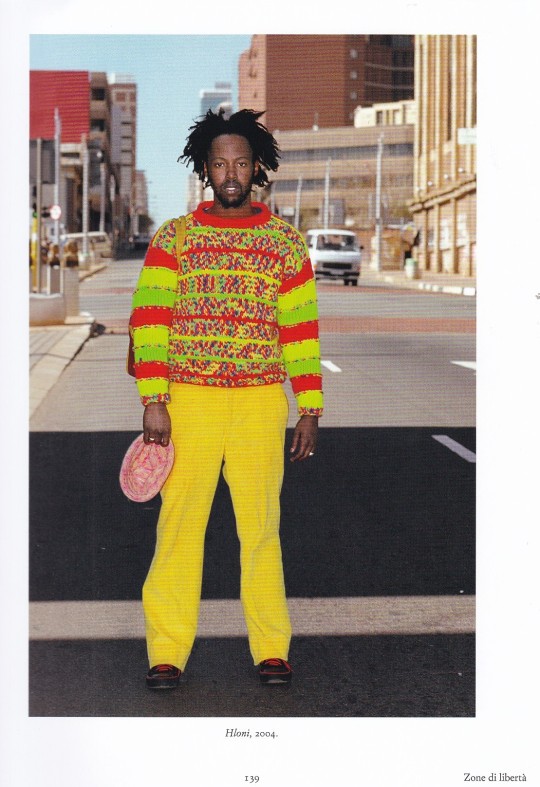

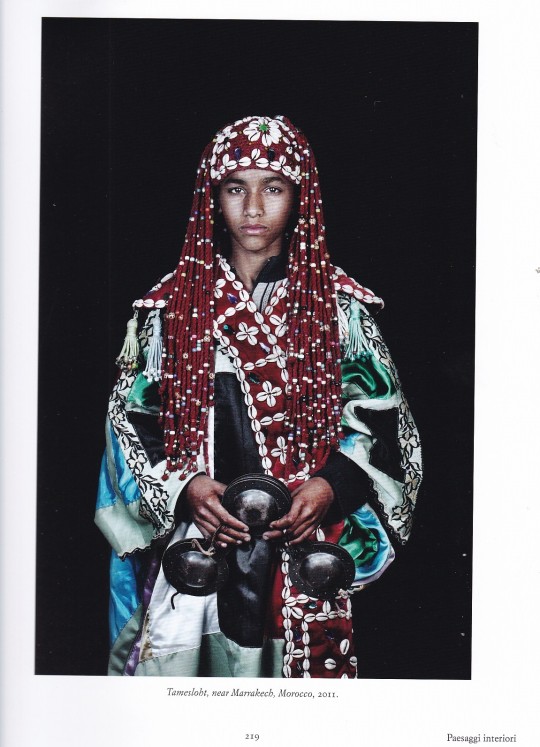

L’Africa del XXI Secolo

Fotografie da un continente

Ekow Eshun

Einaudi, Torino 2020, 272 pagine, 23 x 29 cm, ISBN 9788806245559

euro 70,00

email if you want to buy :[email protected]

Con oltre 300 opere di piú di 50 fotografi, il volume offre una panoramica affascinante di questa fondamentale componente della fotografia contemporanea e costituisce un'imprescindibile introduzione ai suoi protagonisti.

L’Africa del XXI secolo riunisce per la prima volta il lavoro dell’ultima generazione di fotografi appartenenti all’intero continente africano. Sbarazzandosi di una visione occidentale stereotipata, Ekow Eshun esplora i modi attraverso i quali i fotografi contemporanei illustrano l’Africa e l’«africanità» non solo come luogo fisico ma anche come spazio psichico. Dalle tentacolari realtà urbane a paesaggi in continua evoluzione, dalle eredità coloniali e postcoloniali alle tematiche legate al genere, alla sessualità e all’identità, i fotografi compresi nel volume cercano di comprendere cosa significhi realmente vivere in Africa oggi, catturandone i paradossi, le complessità, i drammi, le promesse e le quotidiane meraviglie del suo immaginario.

22/12/22

orders to: [email protected]

ordini a: [email protected]

twitter: @fashionbooksmi

instagram: fashionbooksmilano, designbooksmilano tumblr: fashionbooksmilano, designbooksmilano

#Africa#XXI secolo#Ekow Eshun#300 opere#fotografia contemporanea africana#photography books#fashionbooksmilano

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

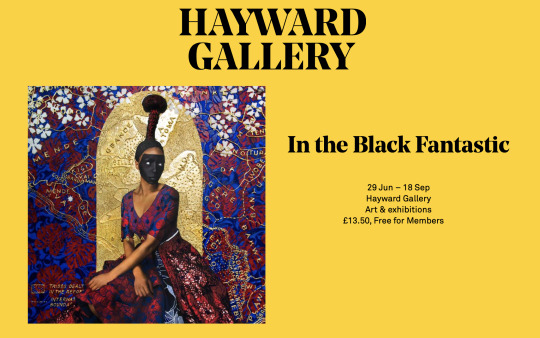

In the Black Fantastic

Hayward Gallery, Southbank Centre, London

Until 18 September 2022

An exhibition of 11 contemporary artists from the African diaspora, who draw on science fiction, myth and Afrofuturism to question our knowledge of the world.

In the Black Fantastic is curated by Ekow Eshun and features the artists Nick Cave, Sedrick Chisom, Ellen Gallagher, Hew Locke, Wangechi Mutu, Rashaad Newsome, Chris Ofili, Tabita Rezaire, Cauleen Smith, Lina Iris Viktor and Kara Walker.

Visit the Hayward Gallery website for more information and to book a ticket

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Live in 20 minutes—Watch Nathaniel Mary Quinn on Gagosian Premieres with performance by Raphael Saadiq

Airing in 20 minutes

GAGOSIAN PREMIERES: NATHANIEL MARY QUINN

Featuring Ekow Eshun, Amanda Hunt, and Raphael Saadiq

Tuesday, November 16, 2021, 2pm EST The ninth episode of Gagosian Premieres celebrates Nathaniel Mary Quinn: NOT FAR FROM HOME; STILL FAR AWAY—an exhibition of new paintings and works on paper at Gagosian, New York—featuring a raw musical performance by Raphael Saadiq; an intimate conversation between Nathaniel Mary Quinn and Amanda Hunt, director of public programs and creative practice at the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art in Los Angeles; and insightful commentary from writer and curator Ekow Eshun. Join Us

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Africa State of Mind

Ekow Eshun’s project offers a kaleidoscopic view of Africa, highlighting over 50 contemporary photographers from the continent and its diaspora.

“In the last 10 years there has been a real increase in exceptional photographers either based on the continent or of African origin. It’s incredibly interesting to see them exploring what it feels and looks like to live in Africa today.” Ekow Eshun (b. 1968) is a British writer, journalist, broadcaster and former director of the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London. His most recent project, Africa State of Mind, is a large, ambitious book.

The publication collects a wide range of images as a platform for expression and exchange around the continent, boasting over 50 exciting names. These next generation artists are providing unique insights into Africa, or, rather, they each offer one of many perspectives. As Eshun points out, there can be no monolithic view. “In the past there were attempts to corral Africans. It’s important to take a broader, much more kaleidoscopic approach. The book presents an overview of recent photographic practice – all the works included were shot in the 21st century, mostly in the last decade. It is an exploration of how contemporary artists of African origin are interrogating ideas of “Africanness” by highly subjective renderings of place, belonging, memory and identity that reveal the continent to be a psychological space – a state of mind – as much as a physical territory.”

That psychological state is complex. Eshun looks back – to the distinguished history of Malick Sidibé (1935-2016) and Seydou Keïta (1921-2001), and even further back to pioneers such as Francis W. Joaque (1845-1900), but also back to the much less illustrious history of photography as practised in Africa by European colonisers. Carving up Africa at the same time photography was being invented, these invaders used images to take stock of what they had seized – via dubious ethnographic studies – and also to create a picture of a “dark continent” that “lent rationale to the apparently civilising mission of Empire.”

Untitled, 2012. © Nobukho Nqaba.

That rationale still contributes to the 21st century image of Africa, says Eshun, from white adventurer movies like Congo (1995), Kong: Skull Island (2017) and Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle (2017) to “the footage of famine-swollen bellies and fly-covered faces that punctuates charity telethons.” This colonial history and resulting hangover of public perception is something with which photographers must engage. “Every time you pick up the camera you are dealing with the legacy of the African figure,” argues Eshun. “That context and history mean that the images aren’t passive. If you’re photographing someone in Africa, you have to ask yourself ‘How is it I think about what it is to do that?’ because you are now in some sort of dialogue with those earlier images.”

However, this extra layer of thought also points to the finesse and refinement in these pictures, he adds – concepts which have always been part of the African experience, though reductive western conceptions have attempted to deny it. There’s often an assumption that these image-makers are somehow catching up with the west, he points out: in fact, Africa has always been “fundamentally cosmopolitan.”

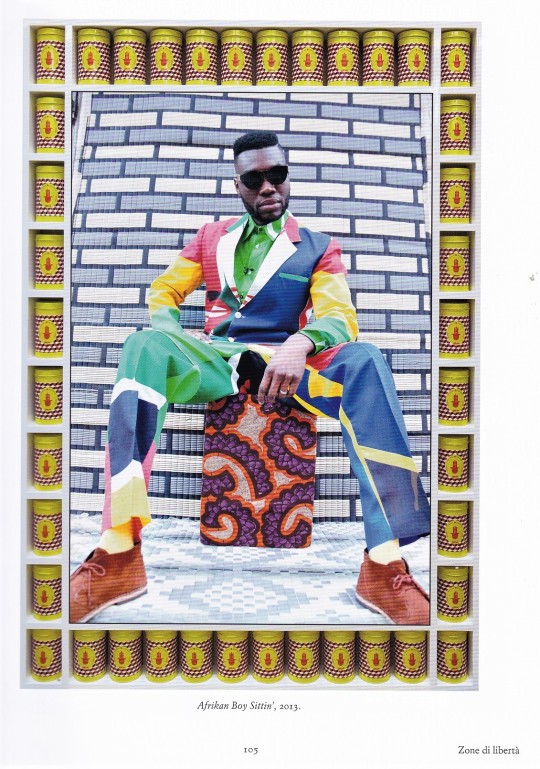

“The west hasn’t historically acknowledged that when you live in Africa, you grow up with this real sense of sophistication, not isolation,” he says. “The art world is opening up, belatedly, to the quality of artists outside the west. Take Zanele Muholi (b. 1972) – the first African photographer to have a major solo show at Tate Modern – something that has nothing to do with anything other than the calibre of the work. Muholi’s practice explores issues of identity, of how individuals can choose to self-identify. Hassan Hajjaj (b. 1961) is a similar example but from a very different place [he’s from Morocco, Muholi from South Africa]. He also uses dynamic portraits as a way of looking at cosmopolitanism and globalisation, gender, identity, masculinity – many different things.”

Mutjope Kavari, Kunene Region, Namibia, 2015. © Kyle Weeks.

Eshun traces similar themes in other photographers’ work. He points to Sethembile Msezane (b. 1991), who uses self-portraiture to address the lack of positive representation of black women in South Africa, and recognition for their part in the country’s liberation. A Zulu woman, Msezane photographed herself dressed as the Zimbabwe Bird in front of a statue of Cecil Rhodes – the Victorian businessman and mining magnate who once ruled South Africa (and elsewhere). This image works in the context of the Rhodes Must Fall protests of 2015, Eshun adds, in which statues of the colonial ruler were removed. “She is inherently very interested in dynamics of power and representation – how we recognise history, point of view and power.”

He also picks out Nobukho Nqaba (b. 1992), another South African who works with self-portraiture, but whose images are most recognisable because of their adornment of cheap, checked bags. “One of her points is that these bags are associated with migration and people on low income, and they are global,” points out Eshun. “They’re made in China, and in South Africa they’re known as ‘China bags,’ but in the USA they’re associated with Mexicans and in Germany with Turkish people. Ultimately, she’s using them as a totemic symbol, using them not just in terms of the relationship that she, as an African woman, has to them, but as how some of these dialogues recur around the world with different sets of people. “These items are a marker of marginalisation, and these images therefore have an implication of the globalisation of capital, or production taking place around the world – there’s a much bigger picture that she’s trying to speak to and interrogate.”

Zakaria Wakrim (b. 1988) is from Morocco. Eshun picks up on a similar sense of “cosmopolitanism” in his work, and in particular an image showing a red-robed individual looking out over the North African coast. The photograph hints at the paths of migration – and forced migration – but also evokes western art history, in its similarity to Casper David Friedrich’s Romantic painting Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (c. 1818). In fact, other images in Wakrim’s series depict the same figure looking over the Atlas Mountains and Sahara Desert. The artist has another westerner in mind – Antoine de Saint Exupéry, the aviator and author who drew on his own experience of crash-landing in the Sahara when writing The Little Prince (1943). “We come back to the decision to shoot an image,” comments Eshun. “These photographers are weighing up their portfolios and placing them within a broader political, cultural and social context.”

Untitled, 2012. © Nobukho Nqaba.

Kyle Weeks’ (b. 1992) practice, meanwhile, engages with what it means be a white Namibian taking pictures of young, black Himba men. Africa State of Mind includes pieces from the series Palm Wine, which shows men following the ancient practice of tapping palm trees for sap; it follows another project with Himba men, in which Weeks set up a portrait studio which allowed them to take photographs of themselves “to give agency to the people in the photographs, and acknowledge his own complicated position … His work highlights the complicated notion of a visual representation of African people,” comments Eshun. “There’s no passive relationship between photographer and subject and context.”

Thinking through these complex ideas, Eshun noticed four themes that seemed to crop up repeatedly. These then became the key chapters of the publication – Hybrid Cities; Zones of Freedom; Myth and Memory; and Inner Landscapes. Hybrid Cities looks at the idea of the metropolis, on a continent that includes three megacities – Lagos, Cairo and Kinshasa – and includes artists such as Thabiso Sekgala, George Osodi, Emeka Okereke and Guy Tillim.

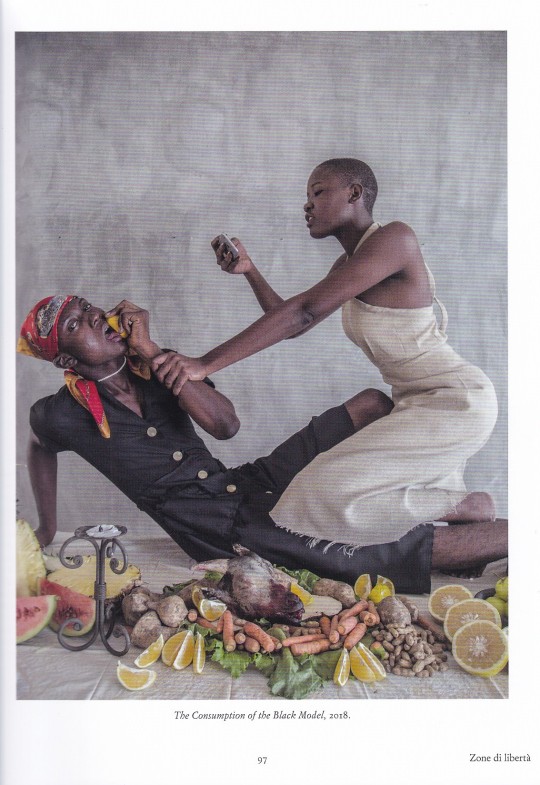

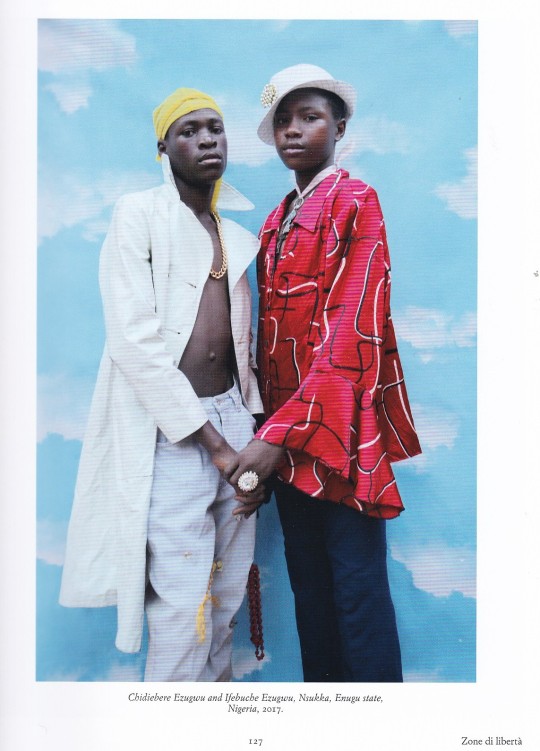

Zones of Freedom considers sexual freedom and identity, and features work by Eric Gyamfi, Hassan Hajjaj, Sabelo Mlangeni, Zanele Muholi and Ruth Ossai. Myth and Memory looks at work that draws on and subverts existing aesthetic traditions, and includes pieces by Omar Victor Diop, Lalla Essaydi, Kiluanji Kia Henda, Pieter Hugo, Namsa Leuba, Sethembile Msezane and Lina Iris Viktor. Inner Landscape focuses in on pictures of people that emphasise the personal and subjective, and highlights names such as Leila Alaoui, Atong Atem, Lebohang Kganye, Youssef Nabil, Nobukho Nqaba, Zakaria Wakrim and Kyle Weeks.

Untitled, 2014. © Zakaria Wakrim.

This decision to organise the book by theme rather than geography is interesting, for at least a couple of reasons. First, it raises the idea that these artists are important because of what they have to say, not because of where they come from. As Eshun puts it, whilst he’s “not averse” to exhibitions and books that focus on particular locations (after all, he has just created one), he doesn’t want it to be the only place to see their work. Instead, he hopes that by throwing the spotlight on under-represented names, this project will help them take their rightful place in the wider canon – as has already happened with Muholi, and with Kiluanji Kia Henda (b. 1979), whose work is currently on show at the Barbican’s, London, Masculinities show, until 17 May.

The second reason for the book’s order hints at Eshun’s own position within this project. He is a London-based man of Ghanaian heritage. Eshun was nominated for the Orwell Prize for the memoir Black Gold of the Sun: Searching for Home in England and Africa(2005) – which deals with a return trip to Ghana, Ghanaian history and issues of identity and race. He isn’t based in Africa, but says that’s not the point. “There is no singular, authentic version of the continent; there are multiple, individual perspectives,” he expands. “Africa encompasses 54 countries! My perspective comes from being of African origin and living in London. I have an inevitably diasporic point of view, but I think it’s valid. I’m not claiming to take a singular fixed view, and I don’t claim to come from some singular version of truth.”

“I want to get away from the idea that ‘This is Africa.’” he continues. “I want to give as much room to the photographers as possible, putting together a book and a show that sees from their point of view. I’m interested in how individual artists, or how I, as a writer, can explore notions and ideas. The photographers are world-present – most of them travel quite often, or, if they don’t, they have an artistic approach and reach that allows them to expand out internationally. It’s not necessarily accurate to think of it as ‘me here, them there’ – it’s more about the flow and exchange of ideas, images and influences.”

— Diane Smyth

1 note

·

View note

Text

New days...

New works

New deeds

"Three shadows remembering light" 2023 as part of the group show in and out of time curated by Ekow Eshun, Gallery 1957.

Production assistance from Nicholas Kwame Ansah, Yaw Donkor and Jibril Salifu Construction by Gershon Gidisu

📸 by yours truly

Featuring

Godfried Donkor

Priscilla kennedy

Zanele Muholi

Yaw Owusu

Lyle Ashtonn Harris

Serge Attukwei Clottey

Gideon Appah

Amoako Boafo

Kwesi Botchway

Tiffane Delune

Timothy Arthur

Todd Gray

Kenturah Davis

Juliann Knxx

Shiraz Bayjoo &

Tunji Adeniyi-Jones

#photography#ghana#eric gyamfi#three shadows remembering their light#Tunji Adeniyi-Jones#Shiraz Bayjoo#Juliann Knxx#Kenturah Davis#Todd Gray#Timothy Arthur#Tiffane Delune#Kwesi Botchway#Amoako Boafo#Gideon Appah#Serge Attukwei Clottey#Lyle Ashtonn Harris#Zanele Muholi#Yaw Owusu#Priscilla kennedy#Godfried Donkor

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

eShun – Party (feat. Kofi Kinaata) (Official Video) Watch the visuals to eShun's new single titled 'Party' with Kofi Kinaata. Video shot and directed by Mickey Johnson.

#alfred eshun quebec#barbara eshun#ben eshun#benjamin eshun#bertha eshun#download eshun akyia#download eshun someone loves me#e eshun someone loves me#ekow eshun#eshop lse#eShun#eshun (zes express)#eshun 2004#eshun 2019#eshun 2019 music#eshun 2019 songs#eshun abc video#eshun afehyia pa video#eshun age#eshun akyia#eshun akyia music#eshun akyia song#eshun am gone#eshun and cabum#eshun and flowking#eshun atanfo#eshun baby#eshun bio#eshun boyfriend#eshun building

0 notes

Text

Now Reading:

Ekow Eshun for The New York Times “Bowie, Bach, and Bebop: How Music Powered Basquiat” (2017)

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/22/arts/design/basquiat-barbican-london.html?rref=collection%2Fsectioncollection%2Fdesign&action=click&contentCollection=design®ion=rank&module=package&version=highlights&contentPlacement=1&pgtype=sectionfront

1 note

·

View note