#Duke of Alencon

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

In the midst of these negotiations, in November 1395, John of Gaunt was negotiating with Jean IV for a marriage between the houses of Lancaster and Brittany for his grandson Henry (later Henry V) with Joan's daughter Marie, which would cement a bilateral alliance between them that Jean IV hoped would get the support he needed to get back both the honour of Richmond and control of Brest.While the matrimonial alliance suited both John of Gaunt and Jean IV, it did not suit Richard II, who reacted angrily to the news when John arrived back in England just after Christmas. Joan wrote two effusive letters to Richard II, in March 1396 and February 1397, to smooth over feathers ruffled by the proposed Lancastrian marriage. In both letters she stressed that she was “desirous to hear of your good estate” and stressed her maternal role by noting the good health of her children. She also noted the good health of her husband in the 1396 letter, with a gentle plea regarding the “the deliverance of his lands”, which appears to reference the ongoing dispute over the honour of Richmond or possibly the restoration of Brest. Joan signed off both letters with pledges that “if anything I can do over here will give you pleasure, I pray you to let me know it, and I will accomplish it with a very good heart, according to my power”.

Elena Woodacre, Joan of Navarre Infanta, Duchess, Queen, Witch? (Routledge, 2022)

#joan of navarre#richard ii#henry v#john of gaunt#jean iv duke of brittany#marie of brittany countess of alencon#historian: elena woodacre#marital negotiations

1 note

·

View note

Text

I previously talked about why I think pushes show gave to Whiteknight do not invalidate Knightfall (or at least Cinder's redemption via Jaune) as potential development and in fact do work well with it. However, I feel like I didn't explain it well in that post. As usual with these types of theories, I will observe it from perspective of Jaune as Joan of Arc.

I previously mostly focused on Weiss as suitor Joan had after her trips to Vaucoulers. Reason being is that it fits chronologically, suitor had full approval of Joan's family and suitor felt entitled to her because of her supposed promise (I interpreted said promise as early volumes Jaune courting Weiss). Joan rejected him because of mission she had to reach Dauphin (and Cinder feels the most as Dauphin allusion). So Joan rejected person that could fit Weiss in favor of being with person that fits Cinder.

In that theory I neglected my Joan of Arc double timeline theory since I mostly wanted to focus on theories in vacuum. However, when you look at it, you also get another person that fits Weiss' role that wanted to be with Joan but got rejected. In that theory I read Weiss as Duke of Alencon for various reasons. Alencon wanted Joan to go with him on campaign, however that request was rejected by French court and Joan was sent on different campaign which eventually led to her capture by Burgundians (which I read as Cinder in this timeline).

So twice at chronologically similar point you have Weiss coded character wanting to be with Joan but are rejected and Joan ends up with Cinder coded character instead.

However, reason is not so simple. Joan rejected her suitor because of divine mission she was given.

"...though I would rather spin by my mother's side, since this is not my calling. But I must go and do this work"

Joan would have preferred she didn't have to do this and instead had a life of regular peasant girl, but she has to do it. And to do it, she disobeyed her parents and cancelled her betrothal, both highly unexpected things for Medieval European girl to do, almost taboo. So if not for her mission, she would have likely married that suitor.

Joan also wanted to go with Alencon on his campaign, but Court sent her elsewhere. So once again, she had to reject something she wanted in favor of staying true to her mission.

Which brings me to Jaune. Being with Weiss is something he wanted in early volumes and something he still might want. It's also something that fits the role he was assigned, being knight to Weiss' symbolical princess. However, Jaune is character that subverts the trope of knight and typical battle shonen protagonist, he also rarely gets what he wants. Way I see it, it would be bit odd for writers to start playing those tropes straight more than half way through the story. So I don't see that theoretical rejection as straightforward no, more of a separation through circumstances that put Jaune on completely different path.

*whispers* Cinder is gonna kidnap him

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joan of Arc by Ernest Hébert (1874)

In lighter mood, Jeanne, meanwhile, must have got a certain amount of pleasure out of her stay at Chinon. It is impossible to regard her as an entirely grim and exclusively serious person. She would be the less lovable were we so to regard her. After all, she was only seventeen; and at seventeen one wants one's moments of relaxation; one wants to enjoy oneself; one wants to play and laugh; one wants the company of one's contemporaries. Jeanne certainly found her best playfellow in the Duke of Alencon—mon beau due, as she called him. This gay, handsome, and attractive young prince of twenty-three was away at Saint Florent, shooting quails, when she arrived at Chinon, but, on learning from one of his servants that his cousin the Dauphin had received a girl claiming to be sent by God to raise the siege of Orleans, his curiosity was so much aroused that he decided to return the next day to Chinon. Here he found Jeanne and the Dauphin together. Jeanne, after enquiring from Charles who the young man might be, greeted him with a graciousness that makes one smile: "You are very welcome [Vous soyez le ires bien-venu]. The more that are gathered together of the royal blood of France, the better."

—Vita Sackville-West, Saint Joan of Arc

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hercule de Valois

Hercule Valois, aka Francois Duke of Anjou and Alencon, would like to challenge (former) Prince Harry to a literary duel.

If Anjou could write a memoir about his life as the “spare” brother, it would be far more entertaining than Harry’s “Spare.”

Elizabeth II seems a much nicer grandmother than Catherine de Medici was a mother to her youngest two children.

{Megan and Harry fans, please disregard this post, this post is for people who know a lot about the Valois family and Catherine de Medici’s children. I don’t know (or care) enough about Megan and Harry to have an opinion on them. I do, however, love to learn about 16th century royal scandals.}

#The Serpent Queen#Valois#Anjou#Duke of Anjou#Duke of Alencon#Marguerite de Valois#spare#Satire#Queen Margot#La Reine de Margot#It's a good thing Margot never went on 16th century Oprah#Though she did write a memoir#16th Century Scandals#16th Century#royal families

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve forgotten just how humorous Elizabeth R is. Watching the Alencon episode last night I had to pause several times because I was laughing. I don’t know if they meant it to be funny but I love how every time Elizabeth gets bad news that makes her angry you don’t SEE her reaction you HEAR it offscreen and her councillors in the foreground are just like :/

#elizabeth r#also the duke of alencon was comedy GOLD#i love my chaotic french gremlin son#period drama#the puritan sermon everyone walks out of...except walsingham#and he's all 'you've only been going 30 minutes. surely you have more?'#also that puritan preacher#chewing the scenery#he looked like mrs proudie at her hammiest#also i forgot about the random bits of nudity#that nine year old me clearly didn't pay much attention to

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m in my joan of arc fangirl era again

#saint joan of arc#joan of arc#jeanne d'arc#saint Jeanne d’arc#charles vii#charles vii of France#henry vi#Jean dunois#Jean Duke of Alencon#Robert de Baudricourt#the Bastard of Orleans

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

French School, ‘Portrait of Prince Hercule-Francois, duc d’Alencon’, c. 1572, French, currently in the collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

0 notes

Text

“...The people around Elizabeth very much wanted Elizabeth to marry. But that is not the sole reason for the various courtships. Despite Elizabeth's supposed dislike of marriage negotiations, she herself encouraged them; she vastly enjoyed the rituals of courtship. Sir Henry Sidney suggested that Elizabeth was "greedy for marriage proposals," a view shared by de Silva. "I do not think anything is more enjoyable to this Queen than the treating of marriage, although she assures me herself that nothing annoys her more. She is vain, and would like all the world to be running after her." At the same time, the actual idea of marriage seems to have been repugnant to her. Elizabeth told the ambassador to the Duke of Wiirttemberg, "I would rather be a beggar and single than a queen and married." She was even more emphatic to the French ambassador. "When I think of marriage, it is as though my heart were being dragged out of my vitals."

And there was the question of what would be the role for a husband of a queen. Elizabeth told de Quadra that, if she married, her husband "should not sit at home all day amongst the cinders," a clever allusion to Cinderella, an already well known tale by that time, and one often told about a "poor cinder boy'' as well as a girl. But one who did not sit in the cinders might well take over control from Elizabeth. Examining her responses, relationships, and others' responses to the marriage negotiations of Archduke Charles, Anjou, and Alencon can allow us insight into this contradiction of image and purpose. Adding further to the ambiguity of the foreign negotiations was Robert Dudley's determined courtship of his queen, and his position as her favorite. Elizabeth's relationship with Dudley was very different from those with her foreign suitors. She knew him well, she apparently had intense feelings for him for many years, and his prospects for marrying the queen came not from the suitability of his birth but from Elizabeth's personal affection for him.

The rumors about Elizabeth's sexual misconduct that abounded throughout her reign almost entirely centered on her relationship with Dudley. In terms of being English and Protestant, Dudley did have certain advantages as a potential husband. He was, however, also the son and grandson of executed traitors, and deeply disliked as an arrogant upstart. Elizabeth, whatever her emotions, kept them sufficiently under control as to not make such a potentially divisive marriage. Dudley was clearly Elizabeth's favorite from the beginning of her reign-they had apparently become friends while both were in the Tower in the reign of her sister. Unfortunately (from his point of view), at the time Elizabeth became queen Dudley was already married, though his wife, Amy Robsart, lived in the country away from court, suffering from what was probably breast cancer. Many people suggested that Robert was simply waiting for Amy to die so that he might marry the queen.

Others thought he might not simply wait. "I had heard ... veracious news that Lord Robert has sent to poison his wife," de Feria's successor, Alvaro de Quadra, Bishop of Aquila, wrote home in November 1559. We have no evidence that Dudley contemplated murdering his wife; however, he may well have not regretted the idea of a natural death for Amy in the not too distant future. But Amy did not die of illness peacefully in her bed. Her death was mysterious and disturbing; on September 8, 1560 she was found dead with her neck broken at the bottom of some stairs in the country house where she was living. Her body was otherwise undisturbed with marks of violence. Many people around Elizabeth were desperately afraid the queen would forget everything in a moment of passion and marry Robert Dudley. We truly do not have all the answers to the questions about Amy's death. Was she murdered? The coroner's court said no, but the verdict never quieted the rumors.

Perhaps she threw herself down those stairs; she was certainly unhappy enough, though this is a particularly uncertain way to commit suicide. Her maid Pinto had overheard her mistress praying to God to deliver her from desperation. On the day she died, Amy sent everyone out of the house to the Abingdon Fair, refusing to go herself, and was angry when her companion decided to stay at home. We might wonder if she wanted to be alone so that she could kill herself. Indeed, some scholars suggest that she may have simply died accidentally, her spine so brittle from metastasized cancer that even the act of walking down stairs-especially if she stumbled-could have cause her neck to snap. Whatever the truth, the scurrilous comments about Elizabeth and Robert Dudley disturbed many people. A marriage with Dudley would have been most unpopular.

But fear of public opinion may not have been the only reason that Elizabeth declined to marry her favorite. She also did not want to give up her control as monarch, as she surely would if she married. Even though Philip was often an absentee husband, his impact on Mary's reign was profound. While Elizabeth was also emotionally involved with Dudley in a way that was unique, she did not allow him to presume too far on his position. When Dudley tried to discipline her servant, Bowyer, the latter threw himself at Elizabeth's feet and humbly craved for Elizabeth to tell him "Whether my Lord of Leicester was King, or her Majesty Queen!" - a question that could not be better calculated to sway Elizabeth's answer. Elizabeth turned to Dudley and told him, "If you think to rule here, I will take a course to see you forth-coming: I will have here but one Mistress, and no Master." Robert Dudley did, however, hope to see England with a master as well as a mistress; he tried both overtly and indirectly to convince Elizabeth that she should marry, and that he ought to to be the man.

As early as 1560 he confided "that if he live another year he will be in a very different position from now." Of course in fact he was not. Elizabeth was well aware of his maneuvers. In 1565 Dudley sponsored a party as a part of the pre-Lenten festivals. De Silva described the events of the day in some detail to his king. We went to the Queen's room and descended to where all was prepared for the representation of a comedy in English, of which I understood just so much as the Queen told me. The plot was founded on the question of marriage, discussed between Juno and Diana, Juno advocating marriage and Diana chastity. Jupiter gave a verdict in favour of matrimony after many things had passed on both sides in defence of the respective arguments. The Queen turned to me and said, "This is all against me." It is hard to know for how long Robert Dudley seriously thought he had a chance to marry Elizabeth, and when the courtship became a game.

Richard McCoy suggests this change happened by the mid-1560s and uses as evidence Dudley's statement (reported in a 4- February 1566 letter from de Silva to Philip) that he did not tell Elizabeth he had abandoned his courtship because "the Queen should not be led to think that he relinquished his suit of distaste for it and so turn her regard into anger and enmity against him which might cause her, womanlike, to undo him." While it is true that Elizabeth and Dudley's relationship did begin to change around 1564-, and that Elizabeth seems to have made up her mind not to marry him but neither to diminish her preference for him, we should not necessarily take Dudley at his word here, though of course he may be telling the truth. It is not at all clear that Dudley had yet given up all hope of marrying his queen. We might question whether instead of misleading Elizabeth, he hoped to convince the Spanish ambassador and the English lords who favored the marriage with Archduke Charles.

Like Elizabeth's, Dudley's statements were often calculated for effect and are not trustworthy guides to what he really thought. Susan Doran, in fact, suggests that those in favor of the marriage with the archduke were such a formidable force at Court that Dudley was afraid to show his hostility publicly. "Instead he chose to negotiate secretly with the French ambassador to sabotage it by putting forward first Charles IX's candidature and then his own." Wallace MacCaffrey states of the period between 1562 and 1569 that "Leicester's position was for obvious reasons a ... difficult one. The prospect of marriage with Elizabeth diminished steadily during these years but he never quite gave up hope." There were a number of obstacles in the 1560s marriage negotiations of Elizabeth to the Archduke Charles, but it also had a number of attractions for the English. The marriage had been suggested by the Austrians and not taken seriously by the English at the very beginning of the reign, around 1559-60.

Despite all de Quadra's attempt to encourage the marriage, Elizabeth then had told the Emperor she had "no wish to give up solitude and our lonely life." Though no one really expected Elizabeth would keep to her "lonely life" at that time, more of the nation supported the idea of Elizabeth marrying an Englishman. By the mid-1560s the situation had changed. In 1563 the idea of the marriage was one again revived, this time by the English, leading to Vienna sending an Imperial envoy, Adam Zwetkovich, Baron von Mitterburg, in 1565. In the mid-1560s the concerns over a disputed succession were acute, especially after Catherine Grey's secret marriage to the Earl of Hertford and her subsequent disgrace. Mary Stuart's position may have been an even stronger motive. Elizabeth may have felt the need to encourage courtships herself when her Scottish cousin was attempting to negotiate an advantageous marriage. Elizabeth was extremely concerned with whom Mary Stuart might marry for her second husband.

"Until 1565, when she finally married her cousin," Susan Bassnett suggests, "the question of Mary's marriage preoccupied Elizabeth as much as that of her own." Mary had made herself available to the Spanish (with hopes of marrying Philip's heir, Don Carlos) and the French (she hoped to marry her brother-in-law, Charles IX, younger brother of her first husband Francis II). Mary even listened to Elizabeth's incredible proposal that she marry Robert Dudley in the hopes Elizabeth would name her as heir as a wedding gift. None of these marriage possibilities worked out, probably due to Mary's own weaknesses as queen, and in the summer of 1565 Mary married her cousin Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley. Despite Elizabeth's own role in narrowing Mary's choices for marriage partners, and allowing Darnley to go to Scotland, both the English queen and the English people were angry and frightened by the implications of this marriage, since Darnley also had some claim to the English throne through his grandmother, Margaret Tudor.

A marriage alliance with the archduke could possibly restore the balance of power lost with Mary's marriage. Among foreign princes there was really none other of comparable status. And a marriage with Robert Dudley, clearly the only domestic candidate by the early 1560s, was unpopular. Elizabeth also recognized that relations with the Hapsburgs needed to be repaired after the ill will that had developed over textile trade between the English and the Netherlands. Yet whether Elizabeth really wanted to marry is another question. In March 1565 she told de Silva: If I could appoint such a successor to the Crown as would please me and the country, I would not marry, as it is a thing for which I have never had any inclination. My subjects, however press me so that I cannot help myself or take the other course, which is a very difficult one. There is a strong idea in the world that a woman cannot live unless she is married, or at all events that is she refrains from marriage she does so for some bad reason .... But what can we do? We cannot cover everybody's mouth, but must content ourselves with doing our duty and trust in God, for the truth will at last be made manifest. He knows my heart, which is very different from what people think, as you will see some day.

Elizabeth certainly believed that a woman, at least a queen, could live unmarried, and do it for the best of reasons. We might wonder what Elizabeth believed God knew was in her heart and what truth would someday be made manifest. Was it that she would never marry, but would rule her entire reign as the Virgin Queen? But, as she admitted, she was pressed very hard, and did agree to to seriously negotiate with the Empire over a marriage with Charles. A large obstacle in the negotiation for the English was Archduke Charles's Catholicism. For Elizabeth herself it was also crucial that she see the archduke before any marriage contract could be signed. It seemed to be an insurmountable difficulty that Elizabeth refused to commit herself before she had actually seen Charles. The emperor's negotiators claimed that Charles would lose his dignity were he to come to England prior to a formal betrothal, but without his coming to England first, a formal betrothal was impossible.

Throughout her reign Elizabeth made the prospect of a successful courtship more difficult by claiming that she could not trust portrait painters. She must see a potential husband before she could decide whether she would marry. De Quadra recorded in May 1559 that "the Queen says that she has taken a vow to marry no man whom she has not seen. . . . And said she would rather be a nun than marry without knowing with whom and on the faith of portrait painters." This ploy was not simply used in the negotiations with the Austrians. For example during the negotiations for Elizabeth to marry the Duke of Anjou (the future Henri III) in the early 1570s, Cecil wrote to Walsingham, who was then her ambassador in France: For the Marriage her Majesty caused me privately to confer with the Ambassador, and her Majesty hath willed me to let him know, that you shall make the Answer, ... her Majesty would have you to let the King and his Mother understand that she cannot accord to take any person to her husband whom she shall not first see.

There were certainly a number of reasons to hold to this position, and Elizabeth had personal experience with some of them. Elizabeth was all too aware of Henry VIII's scathing disappointment when he actually met Anne of Cleves. Her sister's husband Philip, too, had scarcely bothered to hide his contempt for his older queen, despite Mary's passionate love for him. While it was obviously important to Elizabeth that she not be paired with a man she found distasteful, she would also not to place herself in a vulnerable position with a foreign suitor who would not sufficiently appreciate her charms. And Elizabeth's position made sense not only in terms of what would be a happy marriage but in the medical beliefs of the day of what would hasten conception. In the sixteenth-century medical text, The Methode of Phisicke, Philip Barrow argues that "unwilling camall copulation for the most part is vaine and barren: for love causeth conception, and therfore loving women do conceave often."

Elizabeth's position also, however, worked effectively to keep a number of marriage negotiations from going further than she wanted them to go. Elizabeth never wavered on this issue, though as we shall see, even if she did see the potential marriage partner, this was not simply a formality, and did not necessarily mean she would marry. Nor did a potential suitor's willingness to come make her agree to a visit. William Cecil reopened the negotiations with the Empire in 1563, and by 1565 the support for the marriage with Charles included much of the Council; its most vocal supporters included both Thomas Howard, the Duke of Norfolk, and Thomas Radcliffe, the Earl of Sussex. The fear of a disputed succession was so strong in the Council it overrode the question of religious differences. The promoters of the marriage believed the Hapsburgs to be more flexible about religion than indeed was the case.

Cecil was committed to the new religion, but he optimistically believed that Charles would eventually agree to total conformity. Sussex was more realistic about the obstacle of religion but hoped that a compromise could be arrived at whereby Charles would attend Anglican church services with Elizabeth and privately hear Mass. When the negotiations were seriously under way, the open exercise of Charles's Catholicism was the area of greatest dispute. Further areas of disagreement included who should bear the cost of Charles's household in England and Charles's tide and role in governing England. De Silva wrote to Philip that the English thought the Imperial stand on the practice of religion "offered great difficulties .... They also struck at the clause about the Archduke's expenses, thinking that the Emperor wants to burden them with them. With regard to the Emperor's remarks showing that he wishes the Archduke to be called King and to govern joindy with [the] Queen, Cecil thinks this would be difficult .... With regard ... to the request that in case of the Queen's death without an heir, that the Archduke should remain here with a footing in the country, that is a thing they cannot concede, and will never agree to."

While the other issues might have been resolved, Elizabeth was adamant about religion. By the end of August, 1565, Zwetkovich returned to Vienna with Elizabeth's stand and Emperor Maximilian decided "to abandon the matter" unless Elizabeth was willing to modify her position. Elizabeth, however, did not want to see the negotiations ended, whatever she hoped to finally gain from them, and in May 1566 she sent Thomas Danett to Vienna to ask Maximilian to reconsider his position. Susan Doran speculates that this may have been done to avoid a confrontation with her 1566 Parliament over her marriage and the succession. She may also have wanted to keep Philip's good will, at least for a time longer. Maximilian refused to reconsider, however, and Danett also discovered that Charles was a far more devout Catholic, attending Mass daily, than the English had previously believed. Even this news, however, did not keep Norfolk, Sussex, and Cecil from continuing to advance the cause of the marriage.

With Parliament pressuring her, Elizabeth agreed to send Sussex to Austria to further discuss the marriage negotiation. Elizabeth kept postponing his departure, however, and "some feared that the embassy was a mere public relations device intended to silence demands that the Queen marry or settle the succession." This was certainly de Silva's interpretation. He believed that in the end the English would make "an excuse that in consequence of religion, the marriage cannot be effected." Elizabeth finally allowed Sussex to depart; he arrived in Vienna on Augusts. He and Maximilian eventually were able to hammer out a compromise that would allow Charles private worship if he also publicly attended Anglican services with the queen. While there were still some differences in interpretations between Sussex and Charles over what this all entailed, Sussex believed that these concessions would clear the way for the marriage and sent Henry Cobham to England.

Elizabeth said she could not make a commitment without discussing it with her Council. Norfolk, the strongest supporter, was ill and could not attend, and the opponents to the marriage, Leicester, Pembroke, Northampton, and Knollys, pressed their case forcefully, arguing that a Catholic husband would cause religious and political unrest. They were answered by Cecil, Lord Admiral Clinton, and Howard of Effingham, the Lord Chamberlain, who argued that the dangers of a disputed succession and civil war far outweighed any problems over the marriage. After listening to the arguments, Elizabeth decided that she could not allow Charles even the right to have the Mass celebrated in private. Nor was there any point in Charles coming to England in the hope of changing her mind, as she was adamant. Elizabeth's letter to Sussex informing him of this ended all hopes for the marriage, despite Sussex's attempts to salvage the negotiations, and he returned to England in February 1568.

Susan Doran argues intriguingly that though it was Elizabeth herself who eventually killed the negotiations, "it would be a mistake to conclude ... that she had at no point taken the negotiations seriously .... By her own admission, she had reluctantly agreed in 1564 to abandon the single life, for the good of her realm, if a suitable candidate could be found. She made it clear, however, from the first, that she would only marry a man who would practise the same religion as her own." Wallace MacCaffrey suggests that "she was probably not entirely insincere when she expressed her willingness to marry for the sake of her realm. But in her own mind this eventuality remained a remote-indeed, almost an abstract-possibility." We might consider, though, if however much Elizabeth might agree that she would marry for the good of England, in 1565-66 on a deeper level the thought of marriage was overwhelming to her. Despite the pressure of some members of the Council toward the marriage, for Elizabeth it was always something to play with but keep at arms' length.

An incident that occurred with Zwetkovich and de Silva is illuminating. When the Imperial envoy arrived in 1565 he observed of Elizabeth that "although she wished to be a maid and single, she had subordinated her will to the interests of the country, and for its sake would also accept in love him whom the country recommended to her." On July 2 he further wrote to Maximilian "that the Queen becomes fonder of His Princely Highness and her impatience to see him grows daily. Her marriage is, I take it, certain and resolved on." De Silva, who had known Elizabeth far longer than Zwetkovich, may have doubted it and put it to the test. On August 13, 1565 Elizabeth was walking with the two men. Zwetkovich noticed a beautiful ring that Elizabeth was wearing. He suggested that Elizabeth give to him the ruby ring as a token for Charles. Elizabeth refused, but she spoke of longing for Charles to come and visit, since then a marriage could be arranged and he would get much more than one ring from her finger.

De Silva had already had enough experience with the queen to know her great ambivalence at the idea of marriage, and how often she spoke longingly of seeing a suitor she knew to be safely far away. He decided to tease her, and suggest that Charles was already at Court in disguise. I asked her whether she had noticed amongst those who accompanied the Ambassador and me any gentleman she had not seen before, as perhaps she was entertaining more than she thought. The idea horrified Elizabeth. It was easy to wish for Charles's presence as long as he was far away in a distant country. De Silva described Elizabeth's reception to his hint: "She turned white, and was so agitated that I could not help laughing to see her." Only after she got her breath back was Elizabeth able to try to turn the joke around, saying that indeed would be a good way for Charles to come and "I promise you plenty of princes have come to see me in that manner."

Charles never did come to England; by 1568 he finally refused to continue his courtship with the elusive queen, and eventually married elsewhere. For a prince actually to come, however much Elizabeth claimed this was what she wanted, or her even more outlandish statement that this had happened "plenty'' of times, would be pushing the courtship game farther than Elizabeth really wanted it to go. The arrival of a foreign suitor would put the queen in a position where her options would be closed, and make refusing to marry much more difficult. Elizabeth's physical reaction to the possibility of Charles' presence-she apparently nearly fainted-is eloquent testimony to the difficulty of the balancing act she was forever playing. Certainly throughout these lengthy negotiations she convinced members of her own Council that she was serious about marrying. Sussex and Cecil both believed at certain points that she would marry Archduke Charles. So did Dudley, to his great dismay.

Later, during the negotiations with the French, he again believed that Elizabeth might indeed marry, and a foreigner. He wrote to Walsingham in 1571 when the latter was in France negotiating the marriage between Anjou and Elizabeth, "I perceive her Majestie more bent to marry then heretofore she hath been." This may not have been good news to him-a marriage for Elizabeth must have hurt his position as Elizabeth's favorite-as he put in the same letter: "I wish all things to be thoroughly considered of him, that her Majestie may fully understand the condition of his person before hand." A few months later Dudley came to understand that Elizabeth's eagerness for the marriage was pretense. In a subsequent letter to Walsingham, he wrote: "I suppose my Lord of Burleigh hath written plainly to you of his opinion how little hope there is that it [the marriage] will ever take place, for surely I am now perswaded that her Majesties heart is nothing inclined to marry at all."”

- Carole Levin, “The Official Courtships of the Queen.” in The Heart and Stomach of a King: Elizabeth I and the Politics of Sex and Power

#carole levin#history#elizabethan#renaissance#marriage#the heart and stomach of a king#elizabeth i of england

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

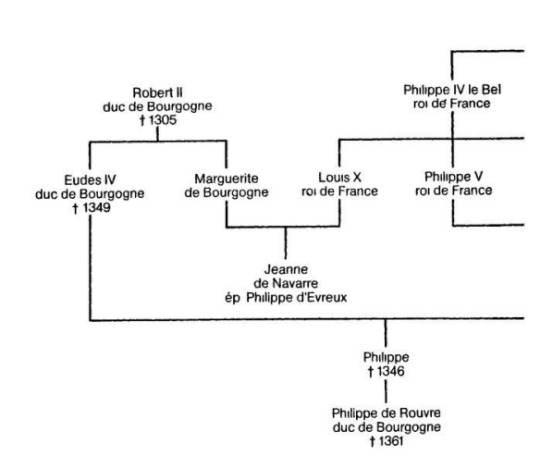

The affair of the succession of Artois and the role of Robert d’Artois in the 100 years war : The Artois affair, provided Philip VI with a new enemy , one who was a complete strange from the rivalries surrounding the French crown, but who will eventually get involved to avenge his own frustration. Robert II of Artois, the nephew of St Louis, died at the Battle of Kortrijk in 1302, leaving a dubious succession beceause his son Philip had died before him. Instead of this son - who died at the battle of Veurne in 1298 - who would have won without any possible dispute over his sister Mahaut, Robert had only a grandson, himself called Robert, as his male heir. No one at the king's court supported this fifteen-year-old boy. Mahaut, on the other hand, was the wife of the precious Otto IV of Burgundy, that disillusioned prince who was going to let the Capetian get his hands on this unexpected land of empire that was the county of Burgundy, in other words, Franche-Comté, almost without a blow. Othon was needed, Mahaut was already powerful, and Saint Louis, in giving it to his brother Robert, had not stipulated that the apanage of Artois was reserved for males. It is known that such a clause only appears in French dynastic law, for Poitou, on the day of the death of Philip the Fair. The law even seems to be favourable to Mahaut. The custom of Artois ignores the representation of the heir son by the grandson. The survivor of the children, girl or boy, prevails. The king and the peers therefore agreed to give Artois to Mahaut and to let her nephew Robert be satisfied with a county that was hardly a county: Beaumont-le-Roger. Since then, Robert of Artois has not missed an opportunity to declare himself despoiled. In 1316, in the great movement of feudal agitation, he led the barons of Artois in a struggle against the countess. From Philip V, with whom he made his peace, he even obtained an investigation, which unfortunately ended up confirming the decision of 1302: the Court of Peers, in May 1318, again rejected Robert's claims to the county. Mahaut's nephew was still only a malcontent. For the most part, he behaved as a French prince and a loyal vassal of his Capetian cousins. Philip V may have been Mahaut's son-in-law, but he entrusted Robert of Artois with various missions.

Charles IV, in turn, showered him with favours and gifts. A brilliant marriage made him, in 1318, the son-in-law of Charles of Valois and the late Catherine of Courtenay, the heiress of the imperial title of Constantinople. Robert d'Artois was therefore the brother-in-law of this Philip of Valois who ascended the throne in 1328. He was also one of those who carried the colours of the Count of Valois to the Council of February 1328. Philip VI remembered him and eventually made him a peer of France and gave him pension after pension. At the Council, Robert d'Artois was listened to. In the royal entourage, he was seen as the man who had the king's ear. For public opinion, he was the king's friend, his companion. He could be satisfied with such a position. On the contrary, Robert feels that the time has come to resume his old quarrel with his aunt Mahaut. The latter had once won, he judged, through favour. and thougt the favour has turned. The times are good . Indeed, there is something new in an area where custom is the law (was not the custom of Artois invoked in 1302 to oust Robert?) and where precedents make the custom.

The Count of Flanders, Robert de Béthune, had just left his county to Louis de Nevers, the eldest of his grandsons, not to those of his sons who had survived their eldest. Robert d'Artois can legitimately think that the custom will henceforth be marked, for himself, by this precedent so close in time as in space. This new episode presents all the aspects of a feudal conflict: alliances between the princes, intervention of the suzerain, judgment of the Court. Robert has the Duke of Brittany and the Count of Alencon, the king's brother, on his side. This is an asset. He made alliances with those whom Mahaut's authoritarianism had thrown into a sort of permanent conspiracy in Artois itself. A former friend of Mahaut's powerful adviser, Thierry d'Hirson, offers her services at the right time. Her name is Jeanne de Divion. In the upcoming trial, Robert d'Artois will have to prove that at the marriage of his father Philippe, Count Robert had expressed his wish that the Artois succession should go to Philippe's descendants rather than to Mahaut's. Jeanne de Divion offered to provide witnesses. In their defence, later, these witnesses will all say that they hesitated to refuse a testimony to the prince who seemed to them all-powerful with the king. The death of Mahaut, in November 1329, precipitated matters.

Philip VI took the county of Artois into his custody, while awaiting a final sentence from the assembled Court, which was expected to favour Robert. It is moreover a baron deliberately at odds with the old countess, Ferri de Picquigny, that the king appoints governor of the pending inheritance. As for Mahaut's heiress, she was Philip V's widow, Jeanne d'Artois, who had once been involved in the adultery of her sister and sister-in-law; she was allowed to pay provisional homage, all the more provisional because she died shortly afterwards. And some opine that this death suits Robert's business very well. In fact, the death of Jeanne d'Artois strengthened Robert's main opponent at the Court of Peers: the Duke of Burgundy, whose wife, the daughter of Philip V, became heiress to Artois if Robert's claim was again rejected. The case was so confused and divided the Court that Philip VI considered for a moment getting out of it in the worst way: by keeping Artois for himself and compensating all the rightful claimants, Robert of Artois and Eudes of Burgundy. By refusing the tax necessary to pay the indemnities, the States of Artois blocked everything. It is obvious that the population would gain nothing from such a solution. It was therefore necessary to put an end to the trial, as a compromise proved impossible for lack of money. The procedure was resumed. On 14 December 1330, the clerks of the Parliament made an expert assessment of the documents provided by Robert d'Artois in support of his claims: they were false. Crude forgeries.

The forger is quickly denounced: it is Jeanne de Divion. One can guess the outcry. Robert's strongest supporters lowered their guard. The king immediately abandoned him. Duke Eudes of Burgundy and his brother-in-law Louis de Nevers, the Count of Flanders, are heard to triumph.It was, moreover, a baron who was deliberately at odds with the old countess, Ferri de Picquigny, whom the king appointed governor of the pending inheritance. As for Mahaut's heiress, she was Philip V's widow, Jeanne d'Artois, who had once been involved in the adultery of her sister and sister-in-law; she was allowed to pay a provisional tribute, which was all the more provisional because she died shortly afterwards. And some opine that this death suits Robert's business very well. In fact, the death of Jeanne d'Artois strengthened Robert's main opponent at the Court of Peers: the Duke of Burgundy, whose wife, the daughter of Philip V, became heiress of Artois if Robert's claim was again rejected. The matter was so confused and divided the Court that Philip VI considered for a moment getting out of it in the worst way: by keeping Artois for himself and compensating all the rightful claimants, Robert of Artois and Eudes of Burgundy. By refusing the tax necessary to pay the indemnities, the States of Artois blocked everything. It is obvious that the population would gain nothing from such a solution. It was therefore necessary to put an end to the trial, as a compromise proved impossible for lack of money. The procedure was resumed. On 14 December 1330, the clerks of the Parliament made an expert assessment of the documents provided by Robert d'Artois in support of his claims: they were false. Crude forgeries. The forger is quickly denounced: it is Jeanne de Divion. One can guess the outcry. Robert's strongest supporters lowered their guard. The king immediately abandoned him. Duke Eudes of Burgundy and his brother-in-law Louis de Nevers, the Count of Flanders, triumphed.

The Court, judging in civil matters, immediately gave its first ruling: Robert d'Artois had no right to his grandfather's inheritance. For the third time, he lost. But now a criminal action begins, which offers all the fishermen in troubled waters the opportunity for a vast unpacking of gossip and resentment. The outcome of such a trial was predictable, for the making of false royal acts is a crime of lèse-majesté. If the king's justice system does not punish the introduction of false or falsified royal acts into social relations with the utmost severity, where will the credibility of the royal seal lie? The king cannot compromise with those who ruin one of the essential means of expressing his sovereign power: jurisdiction, which translates into the sealing of authentic acts. On 6 October 1331, Jeanne de Divion was burned at the stake. There was no way to avoid summoning Robert d'Artois. He saw the danger and preferred to slip away. Moreover, he is now alone. Rightly or wrongly, the production of forgeries is seen as an admission of an indefensible cause. Very few people, such as the abbot of Vézelay, let the clumsy prince know that, forged documents or not, his right to Artois remains well founded. Robert was also ruined. He perhaps boasts that he can easily obtain credit from some financiers in Paris. The bourgeois in question hurried to assure the king that this was not the case. By trying to prove too much, Robert d'Artois sealed his doom.

On 6 April 1332, the Court of Peers sentenced him to banishment. The Duke of Brittany, John III, was the only one of the peers to vote against the sentence. For the time being, the collapse of St Louis' great-nephew had no effect on Franco-English relations. Edward III gave in on the question of homage, which meant that he abandoned any claim to the French crown. He recognised himself, for his Aquitanian duchy, or what remained of it, as the liege of his cousin Philip VI. Now there is a place to be taken in the Council of the King of France: the pre-eminent place that Robert d'Artois had occupied until now. It is understandable that the great barons who, following in the footsteps of Eudes of Burgundy, had recently shown some sympathy for the Englishman, suddenly backed down. Robert d'Artois nonetheless chose, after various peregrinations in Namur, Louvain, Brussels and even Avignon, to take his clientele to England. This is not the effect of an inclination, but there are few other possibilities.

If anyone can ever be the instrument of Count Robert's revenge, it is the English cousin. For Robert does not admit defeat: By me was king. And by me shall be deposed. Disguised as a merchant, he reached England in the spring of 1334. The work of undermining will begin. Although Edward III had reached an agreement with his French cousin, he only wanted to listen to the man who promised him fabulous alliances if he wanted to be vindicated. What Robert d'Artois told the King of England in plain English, no French baron had ever told him before: the son of Isabella of France was closer to the heirs of the Capetians than the Count of Valois. Edward did not need to be told this to think so. Nevertheless, Robert's words gave him ambition.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Margaret of Angoulême, Duchess of Alençon and Queen of Navarre (11 April 1492 - 21 December 1549)

#margaret of angouleme#marguerite of navarre#duchess of alencon#queen of navarre#daughter of charles count of angouleme#married charles iv duke of alencon#then henry ii of navarre#history#women in history#france

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

What’s Out This Week? 2/5

Happy Black History Month!

X-Men & Fantastic Four #1 (of 4) - Chip Zdarsky and Terry Dodson

KRAKOA. Every mutant on Earth lives there ... except for one. But now it's time for FRANKLIN RICHARDS to come home.

It's the X-MEN VS. the FANTASTIC FOUR and nothing will ever be the same.

Darth Vader #1 - Greg Pak & Raffaele Ienco

In the shattering climax of The Empire Strikes Back, Darth Vader infamously reveals his true relationship to Luke Skywalker and invites his son to rule the galaxy at his side. But Luke refuses -- plunging into the abyss beneath Cloud City rather than turn to the Dark Side. We all remember Luke's utter horror in this life-altering moment. But what about Vader? In this new epic chapter in the Darth Vader saga, the dark lord grapples with Luke's unthinkable refusal and embarks on a bloody mission of rage-filled revenge against everything and everyone who had a hand in hiding and corrupting his only son. But even as he uncovers the secrets of Luke's origins, Vader must face shocking new challenges from his own dark past.

Dark Agnes #1 (of 5) - Becky Cloonan & Luca Pizzari

Forced into an arranged marriage, Agnes de Chastillon took matters into her own violent hands to free herself from the yoke of a life she never wanted. Now, the woman known as DARK AGNES, along with her mercenary partner ETIENNE VILLIERS, make their way through 16th century France as sellswords on their way to join the wars in Italy, where the real money is! But when Etienne is captured by the DUKE OF ALENCON's forces and set for execution, it's up to Dark Agnes to save the day! But what evil designs are being enacted on Agnes, and will she doom herself by saving Etienne?

An all-new story following up Robert E. Howard's tales, the swashbuckling saga of DARK AGNES in Marvel Comics starts here!

Immortal Hulk: Great Power #1 - Tom Taylor & Jorge Molina

When Bruce Banner wakes up in the middle of the night without the Hulk, he thinks he's finally free. But the Hulk is immortal - and the night's not over yet. If you thought he was dangerous in the body of mild-mannered Bruce Banner, wait till you see him now. Peter Parker is a man with the proportional strength and agility of a spider, capable of lifting trains on his bad days. And he's about to get a big, green power-up - with a temper to match.

DC Crimes Of Passion #1 - James Tynion IV, Greg Smallwood & Various

Passion. Betrayal. Murder. When you're a private investigator, these are things you experience daily. But when you add capes to the mix-like Batman, Catwoman, and Harley Quinn? Things get even messier. The name's Slam Bradley, and I'm telling you that this year's Valentine's Day special has more intrigue than you can shake a stick at. Ten tales of love-the kind of love that can push people over the edge. Don't miss it...or I'll make you pay.

Whatcha snagging this week, Fantomites?

#What's Out This Week?#WOTW#Crimes Of Passion#Black Agnes#Immortal Hulk#Darth Vader#Fantastic Four#X-Men#comic#comics#comic book#comic books

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

DARK AGNES #1 (OF 5) BECKY CLOONAN (W) • LUCA PIZZARI (A) Cover by STEPHANIE HANS Variant Cover by BECKY CLOONAN VARIANT COVER BY ALAN DAVIS ROBERT E. HOWARD’S SWORDSWOMAN IN HER FIRST SOLO COMIC SERIES! Forced into an arranged marriage, Agnes de Chastillon took matters into her own violent hands to free herself from the yoke of a life she never wanted. Now, the woman known as DARK AGNES, along with her mercenary partner ETIENNE VILLIERS, make their way through 16th century France as sellswords on their way to join the wars in Italy, where the real money is! But when Etienne is captured by the DUKE OF ALENCON’s forces and set for execution, it’s up to Dark Agnes to save the day! But what evil designs are being enacted on Agnes, and will she doom herself by saving Etienne? An all-new story following up Robert E. Howard’s tales, the swashbuckling saga of DARK AGNES in Marvel Comics starts here! 32 PGS./Parental Advisory …$3.99

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

DARK AGNES #1 (OF 5)

BECKY CLOONAN (W) • LUCA PIZZARI (A) Cover by STEPHANIE HANS Variant Cover by BECKY CLOONAN VARIANT COVER BY ALAN DAVIS ROBERT E. HOWARD’S SWORDSWOMAN IN HER FIRST SOLO COMIC SERIES! Forced into an arranged marriage, Agnes de Chastillon took matters into her own violent hands to free herself from the yoke of a life she never wanted. Now, the woman known as DARK AGNES, along with her mercenary partner ETIENNE VILLIERS, make their way through 16th century France as sellswords on their way to join the wars in Italy, where the real money is! But when Etienne is captured by the DUKE OF ALENCON’s forces and set for execution, it’s up to Dark Agnes to save the day! But what evil designs are being enacted on Agnes, and will she doom herself by saving Etienne? An all-new story following up Robert E. Howard’s tales, the swashbuckling saga of DARK AGNES in Marvel Comics starts here! 32 PGS./Parental Advisory …$3.99

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today in history - The death of Isabella of Valois

On June 29, 1406, Isabelle married her first cousin, the eldest son and heir of her uncle, the Duke of Orleans. Based mainly in Blois, she was witness to the growing strife of her family, particularly when her father-in-law was murdered on the orders of Burgundy in November 1407. Siding with her in-laws, she was estranged from her parents who pardoned Burgundy out of necessity until a peace was reached at Chartres in March 1409. By then Isabelle was pregnant with her first child. She gave birth to a daughter, Jeanne, on September and died a few days later on the 13th. She was only 19 years old.

Her second husband, Charles, Duke of Orleans, became a leader of one faction in the ongoing Burgundian-Armagnac civil war. He made a deal with Henry IV’s government in England in 1412/1413 in the hopes of using them to permanently oust Burgundy, however Henry IV’s death in 1413 and Henry V’s accession helped fast-track England’s invasion. He fought at the Battle of Agincourt in October 1415 and was captured. He remained a prisoner in England until his release in 1440.

Her daughter, Jeanne, married Jean, Duke of Alencon in 1424. She died, childless, in 1432.

Isabelle’s younger sister, Katherine, born after Isabelle’s marriage to Richard and raised in the convent of Poissy, married Henry V in 1420 and was the mother of Henry VI. After her husband’s death in 1422 she married Owen Tudor, eventually becoming the grandmother and great-grandmother of Henry VII and Henry VIII.

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sophie Charolotte in Bavaria

Sophie Charlotte in Bavaria (1847-1897) was daughter of Duke Maximilian Joseph in Bavaria and his wife Lukovika of Bavaria, she was younger sister of Empress Elisabeth "Sisi" of Austria. During her life she was fiancée of king Ludwig II. of Bavaria and wife of prince Ferdinand of Orléans, duke of Alencon. Sophie died in Paris in 1897 during fire at age 50.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...In 1564 Melville was at the Court of Elizabeth to negotiate with the English queen about whom she would agree would be an acceptable marriage partner for Mary Stuart. Several times already the chance of the two queens meeting face to face had evaporated. Elizabeth expressed to Melville how much she wished that she might see Mary at some convenient place. Melville replied with the rather startling proposition. I offered to convey her secretly to Scotland by post, clothed like a page; so that under this disguise she might see the Queen . . . telling her that her chamber might be kept in her absence, as though she were sick. . . . She appeared to like that kind of language only answered it with a sigh, saying, "Alas! if I might do this." Though this story may be apocryphal (some of the material in Melville's Memoirs is historically questionable), the suggestion connotes a complicated image: Elizabeth in male garb, but as a male with no power, a page under the protection of a foreign ambassador.

Melville's suggestion can be read as a mirrored but fractured image of the king's two bodies- a body natural and a body politic -that had been re-expressed and refined in the reign of Elizabeth. Elizabeth as queen regularly used male language to present herself. She was a "prince" and "king." But Melville's joke also suggests the fragility and potential lack of power of the queen, the woman, as male. Though of course we do not believe that Elizabeth ever seriously contemplated secretly leaving Court disguised as a boy for a rendezvous in Scotland, the image is a delicious one and reminds us of a number of Shakespeare's heroines who indeed did very comparable actions. Rosalind stole away from Court in As You Like It. Viola was shipwrecked in Twelfth Night. Both these women characters used a male disguise to hide their vulnerability. I am not suggesting that Shakespeare was aware of Melville's frivolous suggestion, but that his drama reflects the fact that a powerful, unmarried woman ruling opened up both the possibility of expanding gender definitions and recognition of the limits of those definitions.

Even Elizabeth herself, despite her effectiveness in using language to present herself as both queen and king, was still sometimes confined by the limits of role expectations. Whatever she might say, and however she might behave, for some of her councillors, she was a woman they were attempting to control, however unsuccessful they might be at it. The image becomes even more confusing when one connects it with some of the drama of the time, where girls disguised as boys, played by boy actors, could be exciting objects of an ambiguous sexuality A boy actor playing a female disguised as a male could be either a powerful professional young man, like Portia as Balthazar in The Merchant of Venice, or a sexually attractive but powerless boy, like Jessica in her male disguise as she elopes with Lorenzo in the same play. And we might consider that Elizabeth's own sexuality was not expressed in a traditionally acceptable female fashion.

This is not to imply that Elizabeth was anything but a heterosexual woman- her interest in Robert Dudley as well as Christopher Hatton and possibly the Duke of Alencon had clear sexual components- but that as queen she did not play the traditional female role in her relations with them. Instead she took on what might be perceived as the male role, certainly the position of power, controlling the courtship and intimacy. Indeed, cross-dressing sometimes represents not power but a sexual freedom that delimits autonomy and power. It is said of Lady Mary Fitton that she disguised herself as a boy to keep an assignation with the Earl of Pembroke. She bore him a son, but the earl refused to marry her, putting her in a most vulnerable, rather than powerful, position. Such disguise for romantic intrigue was not uncommon and not simply the creation of dramatists.

In 1605 Sir Robert Dudley, after he lost his bid to be declared the legitimate son of the Earl of Leicester, fled England for Italy with his nineteen-year-old cousin, Elizabeth Southwell, disguised as his page. The fact that he was married at the time made the elopement even more of a scandal, and the two never returned to England. There were a variety of reasons why women cross-dressed. Some did it for romantic or sexual reasons, while others saw it as a means to challenge traditional attitudes about women's roles. The fact that there actually were women who paraded the streets of Elizabethan and Jacobean London in male garb did definitely upset some men, including James I himself when he became king. In 1583 Philip Stubbes in Anatomy of Abuses describes mannish women as the cause of the downfall of society.

He expressed his shock for women who wear the "kind of attire appropriate onely for man, yet they blushe not to weare it; and if they coulde as well chaunge their sexe, ... I thinke they would as verily become men indeed as now they degenerat from godly sober women." In fact, they are really not women at all: "Wherefore, these women may not improperly bee called hermaphroditi, that is, monsters of both kindes, halfe women, halfe men; who if they were naturall women, and honest matrones, would blush to goe in such wanton and lewd attire, as is proper onely to man." In many ways Stubbes's argument is a precursor of anti-feminist arguments of the twentieth century. In 1588 William Averell also refers to women who "yet in attire they appeare to be men" as "indeede neither" men or women but "plaine Monsters." The controversy became even more intense in the seventeenth century with the Hie-Mulier pamphlet war about women in men's clothings, and James I ordered his ministers to preach against women who would dare dress as men.

R. Mark Benbow has discovered that many of the women arrested in public wearing men's clothes between 1565 and 1605 were accused of being prostitutes. Of course, one wonders if what they were arrested for was indeed prostitution, not cross-dressing, and what their background was. Jean Howard asserts that "It is tempting to speculate that if citizen wives of the Jacobean period assumed men's clothes as a sign of their wealth and independence, lower-class women may well have assumed them from a sense of vulnerability, with an eventual turn to prostitution merely marking the extent of that vulnerability." So, in part depending on class, some women who cross-dressed were more vulnerable, some less. We might at first see cross-dressing as means to power for Shakespearean heroines, paralleling Elizabeth's use of language to present herself as male; however, when we look closely at Elizabeth's rhetoric we see a more complicated strategy, especially as the reign progressed.

Elizabeth not only presented herself as king, but was more comfortable with being a powerful woman who ruled. In the same way we might read the cross-dressed heroines as a means to power, but in such later comedies as Twelfth Night and Much Ado About Nothing, it is the non-cross-dressed heroines who expand gender definitions-who as women act in powerful ways that might, like the actions of the queen, be called "male." Shakespeare was certainly aware of what was going on at Court, and the plays he wrote were sometimes performed there at the express invitation of the queen. As a Londoner, he also had the opportunity to see the queen in her processions through the City. Londoners especially but people in the rest of England as well were very aware of their queen, an awareness Elizabeth deliberately cultivated as a means to promote loyalty.

Not only were there public processions and progresses, but especially after 1585 Elizabeth's speeches to Parliament were copied and sometimes printed for wider distribution, though the printed versions were not always the same as the Parliamentary ones. Elizabeth's speeches were deliberately distributed as widely as possible-copied and printed in chronicles and in separate editions. Her proclamations were officially read aloud throughout the kingdom, and those that were printed were posted as well. Elizabeth not only was aiming her rhetoric at Parliament but was looking for a much wider audience. It is hardly surprising that critics see connections and parallels between Shakespearean characters and the queen. Leah Marcus suggests that "there are remarkable correlations between the sexual multivalence of Shakespeare's heroines and an important strain in the political rhetoric of Queen Elizabeth I."

It is worth examining and analyzing some of these statements by the queen to see how they parallel speeches of the heroines of Shakespeare's comedies. These are hardly one-to-one equations, but rather suggest a fluidity and confluence of ideas of the Court and the drama that express some of the changes in views of gender in the English Renaissance. Dramas were frequently performed at Court, and as we have already seen, particularly in the sacred/ religious aspects of rule, the Renaissance monarch was perceived as an actor on stage, with the "theatrical apprehension of sovereign power," as Steven Mullaney puts it. Righter further argues, "Moving about his realm in the midst of a continual drama, the ruler bears a superficial resemblance to the actor."

Thus the connections we can perceive between Court and drama become that much more interesting, particularly when we consider that only male actors appeared on stage and how some of the plays were staged when played at Court. Sometimes the queen's seat was itself placed on the stage. Stephen Orgel suggests that "there were, properly speaking, two audiences and two spectacles .... At these performances what the rest of the spectators watched was not the play but the queen at a play." Elizabeth often felt "on stage" in much of what she accomplished. She said in 1586 with some discomfort, "We princes, I tell you, are set on stages, in sight and view of all the world." While still King of Scotland, James VI expressed a similar view. In Basilikon Doron James wrote, "It is a trew old saying, that a King is as one set on a stage, whose smallest actions and gestures, all the people gazingly doe behold."

Dudley Carleton echoed this idea when James became king of England: ''The next day the king was actor himself, sat out the whole service, went the procession, and dined in public with his fellow knights, at which sight every man was well pleased." Jerzy Limon further makes the point of how masques were performed "not within the illusionistic stage but in front of it," thus involving the monarch more. In 1600 Ben Jonson even attempted to have Elizabeth appear on stage as a character in Every Man Out of His Humour, but he was forced to change his text. While Elizabeth did not appear as a character on stage in her own lifetime, soon after her death she was the heroine of John Heywood's 1605 If You Know Not Me, You Know Nobody. At the very end of Shakespeare's Henry VIII (c. 1610) she is presented as a baby brought out on stage. Cranmer presents her to the king as a promise of something marvelous to come.

For the audience watching, the speech is a reminder of what the ruler had been. Cranmer proclaims of the baby Elizabeth that She shall be (But few now living can behold that goodness) A pattern to all princes living with her, And all that shall succeed. She shall be loved and feared. Her own shall bless her Her foes shake like a field of beaten corn. (V.iv. 20-23, 30-31) That England's enemies would tremble at Elizabeth suggests her kingly attributes; the promise of this on stage reflects again the confluence between political and dramatic performance. The idea of play, presentation, and performance as the essence of public life and sense of self has been carefully articulated by Stephen Greenblatt, who presents this self-consciousness as peculiar to the Renaissance.

A good example is the advice that Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, offered to his son: "If everyone played his part well that is allotted him the commonwealth will be happy; if not then will it be deformed." Lacey Baldwin Smith comments on this passage: "'Play his part': no metaphor was so common in Tudor England as 'all the world's a stage,' and the higher the actor's rank, the more public and demanding his performance." One gets a further sense of role playing in Viola/ Cesario's comment to Olivia in Twelfth Night: "I am not that I play'' (l.v.182). Elizabeth as the highest in the realm had not only the most exacting part to play, but in fact many different roles, some male/kingly ones. Even in her most casual, seemingly spontaneous remarks, Elizabeth was playing a role, aware of how her audience would respond. Patricia Fumerton contends that, "Each of her gestures toward sincere self-revelation is self-concealing, cloaked in the artifice of politics."

While there may well have been some genuinely open, unpolished, and uncensored remarks to her intimates, what we have recorded as evidence of Elizabeth's speech shows the queen in control, masking what she may be thinking, never telling us completely who she is. Beryl Hughes argues of Elizabeth that "no other English monarch had such an obsession with her own stage management." The fact that males played Shakespeare's heroines adds to gender extension and ambiguity during the English Renaissance. I would certainly agree with such critics as Jean Howard that Renaissance audiences on some level simply accepted boys playing women and thought of them as female characters. Otherwise there would not be an emotional identification with what was occurring on stage. But it is also true that on the stage women could be presented symbolically, a man in women's dress, but a woman as herself could not appear.

We might consider the irony of this at a time when a woman was ruling but felt that to most utilize her power she often had to present herself symbolically as male, as king, rather than as woman. Elizabeth attempted carefully to fashion the way people perceived her and to present herself as king as well as queen of England; to promote this she used male analogies with which to compare herself, and presented herself in a dramatic fashion. We can see this from the very beginning of the reign, in the processions the day before her coronation. As Elizabeth moved through London, the entire city, according to the contemporary tract that described it, became "a stage wherein was shewed the wonderfull spectacle, of a noble hearted princesse toward her most loving people, & the peoples exceding comfort in beholding so worthy a soveraign." The kingly connotations for Elizabeth's rule were established early.

A child from St. Paul's school delivered an oration in Latin comparing Elizabeth to Plato's philosopher-king. And Elizabeth herself continued this male identification. Holinshed’s Chronicle reports that during her coronation procession she stopped to pray at the Tower, where she had lately been a prisoner. In her prayer she compared herself to Daniel, rather than using a female Biblical reference. "I acknowledge that thou hast delt as woonderfullie and as mercifullie with me as Thou diddest with thy true and faithfull servant, Daniell thy prophet; whome thou deliveredst out of the den from the crueltie of the greedie and raging lions: even so was I overwhelmed and only by thee delivered." Certainly there were female Biblical references she might have used. Aylmer's 1559 Harborrowe frequently compares Elizabeth to both Judith and Deborah.”

- Carole Levin, “Elizabeth as King and Queen.” in The Heart and Stomach of a King: Elizabeth I and the Politics of Sex and Power

#history#elizabethan#gender#elizabeth i of england#carole levin#the heart and stomach of a king#renaissance#shakespeare

10 notes

·

View notes