#Dueling Banjo Pigs

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Video

Banjo Pig by John Martz Via Flickr: My contribution to Dueling Banjo Pigs.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

SUBLIME CINEMA #533 - DELIVERANCE

This movie was semi hated when it came out - people didn’t really understand what it was about, abhorred the shocking violence and backwoods stereotyping, and thought it a reductive critique of man vs nature. I think the movie is way more basic. It’s as dark as Herzog’s descents into the abyss, where nature stands for, and provides nothing. There are no lessons to be learned - men always fail.

#cinema#film#films#filmmaking#filmmaker#john boorman#cinematograpjhy#70s#1970s#70s film#deliverance#jon voight#burt reynolds#squeal like a pig#dueling banjos#ned beatty#vilmos zsigmond#man vs nature#nature#nature wins#chaos reigns#canoe#river#rapids#boating#adventure#survival#great film#film stills#dark film

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

#my post#deliverance#deliverance movie#hillbillies#dueling banjos#squeal like a pig#keith the survivor

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I didn't know that there was a soundtrack. And it's on vinyl!

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deliverance (1972) ☆☆☆☆

Ned Director: John Boorman

Writer: James Dickey

The film opens to the wide, expansive, mountainous regions of the Southern States of USA. We are tracking the cars of four friends who have banded together for one final canoe trip through a soon-to-be-gone region of the state. This region – including the river, a town, numerous houses and, outwardly, even its backwards inhabitants – will be flooded by an enormous artificial lake used to generate power for the local city. So the tone is set for Deliverance, a film which is principally about the inadequacies and ignorances of civilised, 20th century men in the wilderness; the mistakes they make, and their scrabbling to atone for these mistakes, often without any luck.

Ed, Lewis, Bobby and Drew arrive at the start of the river with both nervous fascination and patronising contempt for their surroundings, depending on the group member. They think they are alone, but they need volunteers to drive their cars back to the nearest town where the river ends. It turns out they are not alone. A selection of undesirables seep out of the surrounding forestry, and the few dilapidated houses, with disquieting stealth in order to meet the group. They are “mountain people”: filthy, inbred, and with all the physical and mental afflictions we might expect from inbreeding – and all carrying their own looks of contempt for these intruders.

Appearances can be deceiving, though, and through an impromptu ‘battle’, we quickly realise that the locals aren’t to be underestimated. Drew (Ronny Cox), the moral, sensitive heart of our group, is casually plucking at his guitar after the group has arrived at the river. He notices that a small boy, physically lame with an unnerving stare, is copying every note he plays. They begin to duel. (In fact, they play “Duelling Banjos”. A famous song before, the music has become inextricable with Deliverance now.) While Drew plays contentedly, smiling and looking in awe at the boy’s ability, the boy takes a more combative posture. At one point Drew gets lost in the song, and the boy thrashes his ukulele, without faltering, to finish the song and the duel. Ever the gentleman in defeat, Drew holds out a hand, only to be rejected by the boy. It wasn’t a game for him, it was a message.

The men begin their voyage downstream in two canoes. All the canoeing and stunts in this film were done by the cast themselves. This gives the audience a palpable sense of threat, because 3 of the characters – and, indeed, all of the actors – do not seem qualified to be in the rapids. It also means that there’s no need for any dubious editing: figures can move from the background to the foreground of the shot, over very real and very violent swirls of the rapids, and we can see that, yes, these figures in the canoes are indeed the lead actors of the film! This would never happen on film sets today but it makes a marked difference as a viewer. Similarly, Ed (Jon Voigt) really climbed a mountain face for one scene, and again, I cringed at this unmistakably real threat.

This realism also intensifies the now notorious rape scene. Squirm-inducing in 2020, it is hard to imagine how audiences reacted to this singular type of humiliation towards a white, male businessman in 1972. Halfway through the second day, Ed and Bobby (Ned Beatty) pull up their canoe to the river’s shore; the other boys are upstream somewhere. There is no music. The soundtrack is the familiar sound of insects and birds, unchanged since the first time the canoes went into water 50 minutes ago (film minutes). It is a serene sound of nature. Nature will continue to be the soundtrack over the next 8 minutes, as we watch two mountain men confront Ed and Bobby at gun point, forcing Bobby to strip naked. Bobby is then chased, exhausted, toyed with, ridden, forced to “squeal like a pig” and then, finally, raped. To have prepared the audience for this horror with a brooding soundtrack, starting from when they left their canoes, would’ve been obvious and less effective. By guiding the audience with a soundtrack, we remove one of the crucial reasons why the terrifying things that happen to us are so terrifying: there is no warning. Almost invariably, horror arrives in our lives unannounced, from medical diagnoses to rape. With everything else kept constant in the film to this point, such as the setting, pacing and soundtrack, we ask ourselves, how is this happening to them? Is this really about to happen? And our questions recede as the horror unfolds in front of us.

Shorty after, just before Ed is about to at the hand’s of these unsavoury mountain folk, Lewis (Burt Reynolds, of course) shoots the perpetrator through the heart with a bow and arrow, with the other mountain man narrowly escaping. Two questions then arise, one obvious and the other not so obvious: the obvious question is, in a region where everyone knows everyone, how long will it take before the mountain man brings his friends? The other is more subtle and might have been omitted in a lesser version of Deliverance, but is picked up here: what do they do with the body? While the other men seem to have made an implicit agreement amongst themselves already, only Drew remembers that a legal system and society exist outside of this sordid place, a fact so quickly forgotten by the others, to deal with these problems. Drew’s view is not shared by the others; and after a quick vote, it is decided that the dead man is to be buried and forgotten about – and nothing more is to be said on the matter.

As the men make their way back into the river and approach a new set of rapids, Drew, who’s been in a trance since the burial, willingly slumps into the water to his death. The whole affair is too irreconcilably wretched for him. His conscience has overwhelmed him. The men in the other canoe offer the opinion that he was likely shot by the other mountain man. Ed knows better, but in a curious case of self-denial, he begins to agree with them, and even looks for this phantom bullet wound when he finds the body later. It’s as if Ed doesn’t want to believe that their actions are so morally heinous to warrant such martyrdom. After all, as a moral person himself, where would that leave Ed?

The remaining men’s voyage down the river becomes more arduous and more dangerous. There is another death and there are more lies to go with it. They finally arrive in the local town, thoroughly defeated, but not without provoking the suspicion of the local police force. Their story is a little too fanciful to be believed. But they’re in luck, because the town is getting ready for its great burial, and it seems that the town’s imminent death is suppressing the Sergeant’s scepticism on Ed, Bobby and Lewis. At one point, the Sergeant concedes to Ed, “I don’t think you boys should come back. Just let this town die in peace”. In other words, you – and city boys like you – have done your damage to this town, just let the funeral commence; let the slate be wiped clean.

This sentiment of wilful ignorance is reiterated in perhaps the most touching moment in the film. Ed walks into the dining room of the place where he and bobby are rehabilitating. It is dusk, and Bobby is sitting round with several other people, laughing, eating and enjoying himself. It is a picture of warm, Southern hospitality. When Ed sits down, he is quiet and restrained. He says he’s hungry and politely accepts his meal, but within a few moments he has broken down into tears. Whether it’s the picture of Bobby so civilised and unscathed after the horror of the last two days, the hospitality of the locals, or an overwhelming sense of moral responsibility, we don’t know. And the locals – and Bobby – don’t want to know. For no sooner has Ed started crying than he has stopped crying. Let’s move on. The cornbread is delicious. Don’t concern yourself with mistakes, Ed, because they can just as easily be buried – or flooded.

28th May 2020

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Deliverance (1972)

Different genres of film appeal or repulse people to differing degrees. I can stomach an average musical, but I find that I have little patience with an average modern-day action film. The reasons for that are numerous, to be described in another review. John Boorman’s Deliverance is an action-survival film that might seem out of place today – there are long stretches without dialogue or violence and it dares to examine its protagonists’ mindsets as they become victims of violence. Based on the best-selling novel of the same name by James Dickey, Deliverance is a solid entry into the action-adventure tradition. A harrowing film even after the violence has passed, it is nevertheless hampered by its controversial rape scene and reductive depiction of those in the Appalachian American South.

Ed Gentry (Jon Voight), Lewis Medlock (Burt Reynolds), Bobby Trippe (Ned Beatty in his film debut), and Drew Ballinger (Ronny Cox in his film debut) are four Atlanta businessman looking forward to a weekend canoeing down the Cahulawassee River (this river is fictional) before the river valley is flooded by a dam. In the opening minutes, Drew – a guitar player – spots an implicitly inbred boy (Billy Redden) at a gas station. The two share a duet of “Dueling Banjos”, in the film’s most famous scene.The men soon travel downriver, hoping to take in nature’s beauty and to escape from life’s responsibilities. Their desires, however, are shattered when Bobby and Ed are confronted by two men of the mountain (Bill McKinney and Herbert “Cowboy” Coward). For no understandable reason, Bobby – at gunpoint – is forced to strip his clothes. Ed is sexually assaulted as Bobby looks on. One of the rapists is killed by Lewis, unnoticed by the assailants, and the survivor runs deeper into the forest. The men resolve to head to their downriver destination, Aintry, as soon as possible.

youtube

The film’s infamous rape scene does not explicitly show the worst moments, but what is heard is horrifying enough. The cameras show Ned Beatty’s face, distraught and dirt-filled, for far too long. Burt Reynolds himself noticed the camera operators squirming away while director John Boorman continued. Disgusted, Reynolds stood in front of the cameras, asked Boorman why he let the scene run that long, and Boorman responded: “I wanted to take it as far as I could with the audience, and I figured you’d run in when it got too far.” The final cut of Deliverance lingers over the rape; for the audience’s sake, an implied or suggested assault would have been preferable and still respected Dickey’s adapted screenplay of his own novel. Boorman’s lack of restraint – even though some modern directors have even less restraint when presented with such a scenario – damages the film.

Since its release, Deliverance has helped solidify stereotypes about those who live in the American South and how Southern masculinity – bathed in humanity’s and nature’s violence – manifests itself. There is banter aplenty among the protagonists about their physical prowess; the weapons used in this film are phallic suggestions. Much of the pre-release promotion of Deliverance focused on Reynolds’ physicality and how Boorman’s direction pushed his four lead actors through physical pain and natural peril. The four leads, whose characters are from Atlanta, are distinguished from the mountainous locals they encounter at the gas station, during their trip, and in Aintry. Ed, Lewis, Bobby, and Drew represent a suburbanizing, “new” South – a departure from the increasingly urbanized and less white urban South.

In Deliverance, the suburban “new” South meets the Appalachian “old” South. The latter, accustomed to the wilderness surrounding it and wary of the former’s intrusions, is shown as humble and skeptical in Deliverance’s opening minutes to assertive and suspicious by the end of the film’s first act. Boorman depicts the Appalachian Southerners as backwards, their technology and understanding of the outside world decades removed from the present. Their paranoia, Boorman (a Brit who, in post-release interviews, showed little understanding of the poor white Southerners he encountered while making the film) will show, and aggressive territorial behavior can also be argued as self-defense. As Lewis explains to his friends about why they are going on this canoeing trip:

There ain’t gonna be no more river… You just push a little more power into Atlanta, a little more air conditioners [sic] for your smug little suburb, and you know what’s gonna happen? We’re gonna rape this whole goddamned landscape.

The rural Southerners in Deliverance can be interpreted as reacting against industrialized modernity and a white middle class, in defense of an individualistic naturalism that those in cities and suburbs cannot fathom. Their way of life, threatened by the damming project, is endangered – and most likely without their permission. Violence, when law enforcement is sparse, is an acceptable recourse to these people as is sexual assault, Boorman notes. And given how Boorman portrays the poor white men – snaggle-toothed, bone-thin, and underdressed – he is uninterested in providing any depth to these characters. Deliverance sides with the four middle-class whites, never affording the lower-class white characters anything more than their violent “nature.” These stereotypes that Boorman perpetuates are fixtures in how America media views lower-class white Southerners or, in common parlance, “poor white trash.” Look at the lengthy connections page on the films’ IMDb entry; notice how many films and television shows have featured footage or references to Deliverance without context. Numerous mentions and variations of the notorious “squeal like a pig” line appear when one character is threatening another with violence; a child with a banjo or a reference to “Dueling Banjos” brings up character’s fears or perhaps discussion of inbreeding and territorial violence.

Unfortunately, Boorman and Dickey’s approach to how the antagonists are portrayed works just as they want it to. The images that Boorman, cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond (1971’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller, 1977’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind), and editor Tom Preistley (1965’s Repulsion, 1984’s 1984) summon play into a fear of the “other” – placing the antagonist above the protagonist during a frame, keeping the antagonists faceless by positioning them into the background, and wary glances from the four businessman towards the riverbanks as if looking for hidden threats. Not knowing what to expect from this film, I – in my first viewing – found myself unconsciously retreating to damning assumptions even in the opening moments as the Atlantan friends drive up to the gas station (nothing sinister happens at the gas station). My preconceptions have been shaped by various media, assisted (and not started) by Deliverance. In its bourgeoisie discomfort towards underclass whites, Deliverance has helped continue its dreadful ideas about “white trash” – treating them as an existential threat to urban-suburban prosperity and order. This anxiety, an offshoot of the Southern Gothic literary tradition, persists. This reality is, as the locals of Rabun County, Georgia (where this film was shot and where many of the film’s extras resided) will tell you, unfair.

Where Deliverance succeeds is in its psychological treatment of violence. The final twenty minutes of the film – where the men must contend with the police investigation and the personal, extralegal consequences of their actions – would be ignored by many other filmmakers. Beyond the physical acting required for the canoeing scenes and combat against their assailants, this is where the actors shine. Jon Voight is the standout in the closing act, even if Burt Reynolds somehow retains his charm in an otherwise grave moment. The actors convey their characters’ swirls of emotions oftentimes without saying a word in an excellent ensemble performance.

The canoeing scenes in Deliverance were shot on the Chattooga River, which divides northeastern Georgia from northwestern South Carolina. The series of rapids that the production shot on contain some of the most dangerous waters for canoers, kayakers, and rafters in the United States. Such is the Chattooga’s reputation that the likes of Marlon Brando and Henry Fonda backed out of roles when they learned about its rapids. A famous stunt of Burt Reynolds volunteering to send himself over a ninety-foot waterfall in a canoe was inspired by the fact that Reynolds believed that using a dummy was unconvincing. Reynolds break his coccyx on the way down. After returning from the hospital, Reynolds asked Boorman about how the new footage appeared. Boorman’s response: “Like a dummy going a waterfall.”

Whether or not one has seen Deliverance, this is undoubtedly an influential American film – especially how it portrays its Southern characters, the violence they sustain against each other, and the environment surrounding them. A technically effective movie, the stereotypes within have proven resilient before and long after its initial release. It is the film’s undoing and, because of how dominant these views are, its ballast.

My rating: 7.5/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. Half-points are always rounded down. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found here.

#Deliverance#John Boorman#Jon Voight#Burt Reynolds#Ned Beatty#Ronny Cox#Bill McKinney#Herbert Coward#James Dickey#Billy Redden#Vilmos Zsigmond#Tom Priestly#Eric Weissberg#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

1 note

·

View note

Note

Charles squeals like a pig when he's being raped

*Dueling Banjos*

1 note

·

View note

Text

Deliverance (1972) ☆☆☆☆

Director: John Boorman

Writer: James Dickey

Deliverance opens to the wide, expansive, mountain regions of the Southern States of USA. We are tracking the cars of four friends who have banded together for one final canoe trip through a soon-to-be-gone region of the state. This region – including the river, a town, numerous houses and, outwardly, even its backwards inhabitants – will be flooded by an enormous artificial lake used to generate power for the local city. So the tone is set for Deliverance, a film which is principally about the inadequacies and ignorances of civilised, 20th century men in the wilderness; the mistakes they make, and their scrabbling to atone for these mistakes, often without any luck.

Ed, Lewis, Bobby and Drew arrive at the start of the river with both nervous fascination and patronising contempt for their surroundings, depending on the group member. They think they are alone, but they need volunteers to drive their cars back to the nearest town where the river ends. It turns out they are not alone. A selection of undesirables seep out of the surrounding forestry, and the few dilapidated houses, with disquieting stealth in order to meet the group. They are “mountain people”: filthy, inbred, and with all the physical and mental afflictions we might expect from inbreeding – and all carrying their own looks of contempt for these intruders.

Appearances can be deceiving, though, and through an impromptu ‘battle’, we quickly realise that the locals aren’t to be underestimated. Drew (Ronny Cox), the moral, sensitive heart of our group, is casually plucking at his guitar after the group has arrived at the river. He notices that a small boy, physically lame with an unnerving stare, is copying every note he plays. They begin to duel. (In fact, they play “Duelling Banjos”. A famous song before, the music has become inextricable with Deliverance now.) While Drew plays contentedly, smiling and looking in awe at the boy’s ability, the boy takes a more combative posture. At one point Drew gets lost in the song, and the boy thrashes his ukulele, without faltering, to finish the song and the duel. Ever the gentleman in defeat, Drew holds out a hand, only to be rejected by the boy. It wasn’t a game for him, it was a message.

The men begin their voyage downstream in two canoes. All the canoeing and stunts in this film were done by the cast themselves. This gives the audience a palpable sense of threat, because 3 of the characters – and, indeed, all of the actors – do not seem qualified to be in the rapids. It also means that there’s no need for any dubious editing: figures can move from the background to the foreground of the shot, over very real and very violent swirls of the rapids, and we can see that, yes, these figures in the canoes are indeed the lead actors of the film! This would never happen on film sets today but it makes a marked difference as a viewer. Similarly, Ed (Jon Voigt) really climbed a mountain face for one scene, and again, I cringed at this unmistakably real threat.

This realism also intensifies what is now the film’s most notorious scene. Squirm-inducing in 2020, it is hard to imagine how audiences reacted to this singular type of humiliation towards a white, male businessman in 1972. Halfway through the second day, Ed and Bobby (Ned Beatty) pull up their canoe to the river’s shore; the other boys are upstream somewhere. There is no music. The soundtrack is the familiar sound of insects and birds, unchanged since the first time the canoes went into water 50 minutes ago (film minutes). It is a serene sound of nature. Nature will continue to be the soundtrack over the next 8 minutes, as we watch two mountain men confront Ed and Bobby at gun point, forcing Bobby to strip naked. Bobby is then chased, exhausted, toyed with, ridden, forced to “squeal like a pig” and then, finally, raped. To have prepared the audience for this horror with a brooding soundtrack, starting from when they left their canoes, would’ve been obvious and less effective. By guiding the audience with a soundtrack, we remove one of the crucial reasons why the terrifying things that happen to us are so terrifying: there is no warning. Almost invariably, horror arrives in our lives unannounced, from medical diagnoses to rape. With everything else kept constant in the film to this point, such as the setting, pacing and soundtrack, we ask ourselves, how is this happening to Bobby? Is this really about to happen? And our questions recede as the horror unfolds in front of us.

Shorty after, just before Ed is about to suffer his turn at the hand’s of these unsavoury mountain folk, Lewis (Burt Reynolds, of course) shoots the perpetrator through the heart with a bow and arrow, with the other mountain man narrowly escaping. Two questions then arise, one obvious and the other not so obvious: the obvious question is, in a region where everyone knows everyone, how long will it take before the mountain man brings his friends? The other is more subtle and might have been omitted in a lesser version of Deliverance, but is picked up here: what do they do with the body? While the other men seem to have made an implicit agreement amongst themselves already, only Drew remembers that a legal system and society exists outside of this sordid place, a fact so quickly forgotten by the others, to deal with these problems. Drew’s view is not shared by the others; and after a quick vote, it is decided that the dead man is to be buried and forgotten about – and nothing more is to be said on the matter.

As the men make their way back into the river and approach a new set of rapids, Drew, who’s been in a trance since the burial, willingly slumps into the water to his death. The whole affair is too irreconcilably wretched for him. His conscience has overwhelmed him. The men in the other canoe offer the opinion that he was likely shot by the other mountain man. Ed knows better, but in a curious case of self-denial, he begins to agree with them, and even looks for this phantom bullet wound when he finds Drew’s body later. It’s as if Ed doesn’t want to believe that their actions are so morally heinous to warrant such martyrdom. After all, as a moral person himself, where would that leave Ed?

The remaining men’s voyage down the river becomes more arduous and more dangerous. There is another death and there are more lies to go with it. They finally arrive in the local town, thoroughly defeated, but not without provoking the suspicion of the local police force. Their half-baked story is a little too fanciful to be believed. But they’re in luck, because the town is getting ready for its great watery burial, and it seems that the town’s imminent death is suppressing the Sergeant’s scepticism on Ed, Bobby and Lewis. At one point, the Sergeant concedes to Ed, “I don’t think you boys should come back. Just let this town die in peace”. In other words, you – and city boys like you – have done your damage to this town, just let the funeral commence; let the slate be wiped clean.

This sentiment of wilful ignorance is reiterated in perhaps the most touching moment in the film. Ed walks into the dining room of the place where he and Bobby are rehabilitating. It is dusk, and Bobby is sitting round with several other people, laughing, eating and enjoying himself. It is a picture of warm, Southern hospitality. When Ed sits down, he is quiet and restrained. He says he’s hungry and politely accepts his meal; but within a few moments he has broken down into tears. Whether it’s the picture of Bobby so civilised and unscathed after the horror of the last two days, the hospitality of the locals, or an overwhelming sense of moral responsibility, we don’t know. And the locals – and Bobby – don’t want to know. For no sooner has Ed started crying than he has stopped crying. Let’s move on. The cornbread is delicious. Don’t concern yourself with your crimes and mistakes, Ed, because they can just as easily be buried – or flooded.

28th May, 2020

0 notes

Text

Dueling Banjo Pig by Vandão

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Who effed me more?

Dorothy for using K-Y warning jelly personal lubricant to oil my squeaky parts

or that man behind the curtain...when he got a wiff of the K-Y Jelly...let’s just say I walked like I rode a horse in the Boston Marathon...slowly...then when he said “squeal like a pig 🐷...with “Dueling Banjo’s”🪕 was playing over the loud speaker...that was the last straw...

rotcivnasrab

Got a Heart? ❤️ my butt!

Tin Woodman by Yan Blanco

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Deliverance (1972)

#my post#deliverance#jon voight#burt reynolds#ned beatty#ronny cox#squeal like a pig#canoe#canoe trip#dueling banjos#hillbillies#keith the survivor

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

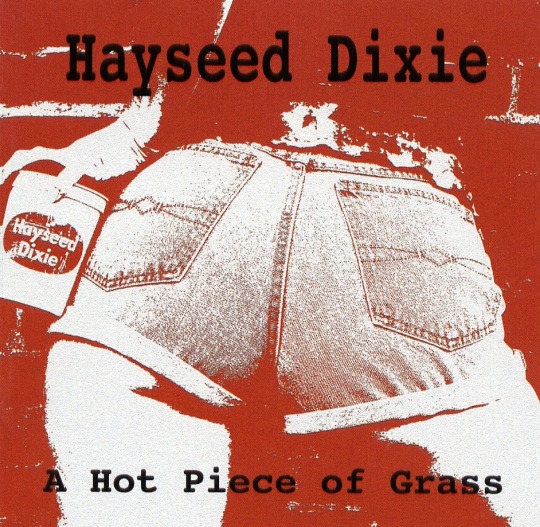

Hayseed Dixie – A Hot Piece Of Grass Tracklist Black Dog War Pigs Holiday Ace Of Spades Whole Lotta Love Whole Lotta Rosie Runnin' With The Devil Blind Beggar Breakdown Kirby Hill Mountain Man Marijuana Corn Liquor Moonshiner's Daughter Dueling Banjos

0 notes

Photo

Can’t say I feel it...’cept on the bottom of my moccasins.. Dang it!... I think I might have stepped in it! It smells like...

SKUNK POOP 💩to me...

Suppose even Skunk 💩...May be better... compared to playing Dueling Banjo with BIG BOOGER in a...5 X 8 Prison Cell!

sing like a pig 🐷

✔️

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Even More Russian Antics

ahahahahaha i can’t stop making these :D

updates, how to get kicked out of russia, and i like how they turned out. So have a laugh! (No skaters were harmed in the making of these little pranks. Possibly. Well, what else do you expect from Yurio???)

Enjoy 41-80!

333 Ways To Get Kicked Out Of The Rink And Russia Itself

1. Switch the drinks at the banquet with random condiment liquids.

Yuuri was more than confused when he went to drink some of the fruit punch and found it was just watery filtered ketchup with lemons thrown in. Yurio was nowhere to be seen.

2. Hit people with pirozhki's.

This backfired on Yurio when Viktor's hair became a victim. He went MIA after said older Russian skater finally caught him….

3. Walk up to some old geezer and yell, “Grandpa! You're alive! It's a miracle!”

Viktor wouldn't stop sulking under the benches in the locker rooms when Yuuri tried this….

4. Dart around suspiciously humming the Mission: Impossible theme song.

Everyone was highly concerned for Phichit's mental state.

5. Buy several dozen fishing rods. Go on the roof and test them out, saying you're fishing for toupees.

Mila caught 35, Yurio got 31, and Georgi won with a staggering 108.

6. Hold Barbie hostage.

Yurio didn't really mind, Otabek was his friend after all. Besides, he quite liked the horrified looks of his fans when the Kazakhstan skater grabbed him as he sped by on his motorcycle.

7. TP as much of the rink as you can.

Nobody suspected innocent Yuuri to be good with his throwing arm, but almost every inch of the rink was covered in toilet paper. Viktor was automatically blamed.

8. Hide in the skate racks. Whenever someone comes to grab a pair, yell “Pick me! Pick me!”

Yuuko was incredibly unimpressed when the triplets pulled this prank on their father. However, hearing Takeshi scream like a child was worth it, and they all got ice cream that night.

9. Dress as Batman and burst into the rink screaming, “Come Robin! To the Batmobile!”

Guang-Hong was just extremely confused at Leo's antics, wondering if all Americans were this weird.

10. Challenge people to duels with wrapping paper.

It was the best birthday yet, in Viktor's opinion.

11. Buy several singing toy Viktor's from Amazon, and once you have them, set them up on the ice and get your friends to turn them on. Proceed to act like a conductor.

Yuuri was actually really good at anything music related. The impromptu concert certainly amused the others.

12. Go up to random people and poke them. If they ask what you're doing, inform them that you're trying to find out what they ate for breakfast.

Georgi got kicked across the room when he tried this on Yurio.

13. Leave cryptic messages all over Instagram as an anon.

Nobody knew Phichit could even scream that loud.

14. Skate around screaming “There's a dead body in here!”

Yakov was unamused at Mila's actions.

15. Go up to the Russian Fairy and say, “Yurio, I am your father.”

It wasn't even remotely funny for Viktor. It just opened up more wounds.

16. Make evil eyes at people and whisper “I am the Lady Of The Well…..i've been waiting...”

Minako's Halloween party was the bomb.

17. Ride around in a Barbie car and pretend to be a posh upperclassman, sipping vodka from a teacup and saying things like “Top hole!” and “By Jove!”

Yuuri should have never let Minako watch Doctor Who.

18. Start dancing like mad. Wave your arms and flop like a fish.

Everyone assumed Yuuri was drunk again. The ensuing dance battle was certainly better than last year.

19. Balance everything you see on the tip of your nose, fingers, on your forehead, and top of your head all while singing the circus song.

Otabek won with 4 water bottles, Yuuri's duffle bag, 5 pairs of ice skates, and Yurio, all while skating circles around Phichit, who was filming the entire thing.

20. Start singing songs through the PA system at the ice arena.

The entire skating crew all joined in on a perfect rendition of Stammi Vicino. The announcers were extremely entertained.

21. Blackmail your friend into giving you a piggy back and have them run around the town, screaming “The Russians are coming! The Russians are coming!”

The next GFP was certainly better prepared after Yuuri and Phichit gave the warning. Though Phichit on Yuuri's back was certainly a weird mode of transport….

22. Take a fishing pole, a bag of money, and go people fishing.

Georgi was still bored, and eventually caught Yurio.

23. Pretend to be Spiderman by running up walls and saving people.

Guang-Hong really had to get Leo to stop watching those superhero movies of his, this was getting ridiculous.

24. Pretend to have an asthma attack, and bite anyone who tries to help you.

Emil went to the doctor after Yurio pulled this stunt in Barcelona… that's what he got for trying to be a nice friend…..

25. Lie on the ground. Just lie there. It's guaranteed to freak people out.

Revenge for the Grampa joke. Yuuri was panicking like crazy when Viktor pulled this stunt after a failed jump.

26. Announce an ice sliding contest. Take off your skates and proceed to do just that.

The game had to stop after Georgi slid too far into the rink wall.

27. Put on a black ski mask and cape and run around declaring “Zorro has returned!”

Nobody was sure where Sara went during the hours when a masked vigilante ran rampant through Russia.

28. Protest against cat abuse.

Nobody knew what the fuck just happened after Yurio ran down the streets, completely drunk and screaming “Run my feline friends! Run!” at the head of a cat stampede.

29. Start a barbershop quartet.

Yuuri, Viktor, Chris and Phichit soon become number one on the charts with their hit song, When Drunk People Dance On Poles.

30. Dress in a trenchcoat and sunglasses, go up to random people, hand them marshmallow guns, and say, “You know what to do.”

Thus started Russia's Marshmallow War 1, thanks to Phichit stealing Viktor's clothes.

31. Go up to random people carrying a paper bag and say “Trick or treat!” When they refuse, give them puppy dog eyes.

Guang-Hong's legendary puppy eyes were something to fear.

32. Cover your hand with blue paint. Run up to someone, put your hand on their face and yell “A clue! A clue!”

Yurio's knife shoes were the talk of the town after JJ tried this on the Russian Fairy and subsequently had to go to the hospital for minor lacerations.

33. Scream really loudly and when someone asks you to be quiet, scream, “I WON'T BE SILENCED!”

Apparently, Yuuri was trying out a new anxiety coping method.

34. Grow out your hair.

Needless to say, Yuuri and Viktor disappeared for a little while once Viktor noticed how long Yuuri's hair had gotten… Yurio was disgusted.

35. Grab a can of whipped cream, find a bald guy, and spray it on him.

Yakov blasted Mila's eardrums for that one.

36. Start singing horrible karaoke.

Nobody's ears were ever the same after Mickey took the mic.

37. Loudly announce that you will be the one to win gold this year.

Yuuri actually didn't care, he just wanted to see the chaos.

38. Go magical creature hunting.

Yurio was unamused at Otabek and Phichit.

39. Run up to someone, slap them, and scream, “WHAT IS THIS?!? I THOUGHT WHAT WE HAD WAS SPECIAL!!!”

Viktor stared after Yuuri in horror, holding his damaged cheek. He was just talking to Chris!

40. Fall over and scream “Ah! The pain! The terrible pain!” When someone asks what's wrong, stand up and say “Nothing, why?” and walk away as if nothing had happened.

Chris just liked making people's days a little more surreal.

41. Dress up as an emo person, and whenever someone talks to you, scream, “WHY HAVE YOU COME TO WORSEN MY MISERY?!?”

“Mila, is Georgi always like this?”

“You'll get used to it, Yuuri.”

42. Host your own radio show.

Phichit and Otabek made a great commentary team.

43. Hide a walkie-talkie somewhere and whisper, “I know where you live.”

Yuuri's scream was worth it, in Yurio's opinion.

44. Run around Russia in a swimsuit singing “Surfin' USA”

Note to self, NEVER LET LEO NEAR THE VODKA. Phichit recorded the whole thing, and Leo became a meme.

45. Look for Narnia.

Viktor thought this was hilarious when he managed to pull a dazed Yuuri out of his wardrobe.

46. Release pigs into the rink labeled 1, 2 and 4.

They lost it when Yurio calmly taped a piece of paper labeled “3” on Yuuri's back.

47. Go on a road trip.

You've seen the official art, why are you asking me?

48. Learn to play the banjo.

Once again, Yuuri dazzled the Russian Crew with his music skills, and the ensuing hoedown inspired a new routine or two.

49. Go mattress surfing.

It was Phichit's idea, and it made Detroit a lot more fun than before, in Yuuri's opinion.

50. Hold a snowball fight.

Yurio was terrifyingly good at this.

51. Sing everything you say, and when questioned, inform them that you're in a musical.

Even Yakov joined in, and Musical On Ice was a huge success.

52. Play Human Dominoes

Otabek's day just got that much better.

53. Crash a party.

Episode 10, anyone?

54. Create a giant conga line.

Jesus, how many fans did JJ have???

55. Have a rap battle.

Nobody knew Otabek could rap that fast, but he did. Very well. He was, however, beaten out by Yuuri.

56. Get a pinata and bust it open.

Yurio had taped JJ's picture on it. It was a great stress reliever.

57. Dress someone up as a chicken.

Minami had no idea what was going on, but he went along with it.

58. Play frisbee on the ice.

It wasn't a problem until they nailed Yakov in the face.

59. Write angsty and gory fanfiction.

Nobody was the same after finding Yuuri's account.

60. Stage a riot.

“WHAT?! YURATCHKA DIDN'T WIN OVER JJ???”

“THOSE BASTARDS!'

“GET THEM!”

61. When someone asks for your help, begin to cry and say, “Why won't you people leave me alone?!”

Everyone was alarmed when Celestino burst into tears every time someone asked him for help on jumps.

62. If a skater with more than one gold medal comes within 30 feet of you, scream “GET AWAY FROM ME!!!” and run out of the area.

Viktor started sobbing when everyone careened away from him, even his beloved Yuuri. JJ was just confused.

63. Glare menacingly and hiss like a pissed off cat whenever someone comes near you.

Yurio had half the town terrified, with the glares, hissing, and raising of a leg with a freshly sharpened knife shoe attached.

64. Cover your face with cream cheese and thunder down the streets of Saint Petersburg chanting “We love bagels! We love bagels!”

Another reason why Yakov needed headache medicine after he forgot the breakfast bagels one time.

65. Run around singing, “I KNOW A SONG THAT GETS ON EVERYBODY'S NERVES!”

Yuuri hid in the lockers, only for the rest of the skater crew to bust down the door, still singing.

66. Dress up like a fairy, climb up a ladder and say to every person that passes by, “Your wish is granted!”

Drunk Yurio is best Yurio, until he started crying when he realized he was afraid of heights.

67. Ride in a Barbie sports car with Barbie in the backseat and say “Let's bust this joint!”

Yurio had to admit, that Viktor certainly had an interesting choice of vehicles to ride in.

68. Wrap a hose around you and scream, “AH! I'M BEING HELD HOSTAGE!”

The scary thing was, Guang-Hong wasn't joking.

69. Walk up to someone and act like you can read their mind, then say, “Sir/Madam… don't do that.”

Yurio was stunned speechless when Otabek told him this just seconds after he had come to the decision of cutting JJ.

70. Hit your head and say, “Shut up in there!”

Everyone was extremely concerned for Yuuri.

71. Act as though you're being beaten and fall to the ground, screaming and having convulsions.

Georgi's performance got a 10/10 rating from the rest of the skaters.

72. Swing on the banners.

Apparently, dance battles were not enough for drunk Yuuri, and soon the “Congrats On The Gold!” banner was ripped on the floor while Yuuri sobbed over his aching bum, and for once it wasn't Viktor's fault.

73. Grab heavy, but not too heavy objects and see who can throw them the farthest.

The game had to be discontinued when Seung-Gil calmly picked up Yurio.

74. Knock over all the tables at the banquet and scream, “EARTHQUAKE! EVERYBODY RUN!!!”

Phichit was having too much fun in California, and scared the living hell out of Leo when he pulled this.

75. Hold a 12 pack of vodka over your head and shout “FEAR ME AND MY ARMY OF ALCOHOL!!!”

Viktor and the Russian gang actually conquered a bit more territory for Russia this way, by invading towns and getting the villagers drunk off their asses.

76. Get popcorn and throw it at people, sneaking up to them unstealthily and screaming war cries.

Russia War 2 commenced when JJ threw the first kernel at Yurio.

77. Try on all of Viktor's old costumes and go to the rink and proceed to do the worst, overly dramatic impression of him you can manage without falling over in laughter.

If Viktor hadn't been laughing so hard at Yuuri and Yurio, he probably would have been lightly offended and possibly crying, but no, it was too funny seeing them flip their hair and say dramatic things in Russian, with Phichit recording everything.

78. Stare at the ceiling. See how many people look up.

Yakov felt immensely proud when he pulled this on his skaters and it worked.

79. Dress up as a ninja and go around karate chopping people.

Mari was quicker than she looked, and the only hint of a warning anyone got before they were chopped was a flash of dirty blonde brown hair and the smell of cigarette smoke.

80. Climb up to a tall place and scream until someone comes. If they try to get you down, scream, “HELP! KIDNAPPER!”

It was funny until Yurio realized he was actually stuck.

#ice skate gang#yuuri katsuki#viktor nikiforov#yuri plisetsky#yurio#yoi#yuri on ice#funny#my writing#entertaining#hope this makes your day a little bit brighter#the entire yoi cast

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Down by the Bay verses I have accumulated:

Have you ever seen a fox with a hole in his socks?

Have you ever seen a bear braiding his hair?

Have you ever seen a whale wagging its tail?

Have you ever seen a mouse constructing a house?

Have you ever seen a dragon pulling a wagon?

Have you ever seen a parrot growing purple carrots?

Have you ever seen a giraffe faking a laugh

Have you ever seen a chicken practice banjo pickin'?

Have you ever seen a lizard dueling a wizard?

Have you ever seen a pig styling a wig?

Have you ever seen a goose kissing a moose?

Have you ever seen some kittens knitting tiny mittens?

Have you ever seen a fish making a wish?

Have you ever seen a squirrel on a tilt-a-whirl?

....

I'll probably

0 notes

Photo

Dueling Banjo’s

Deliverence

Squeal like a pig 🐷

✔️

90 notes

·

View notes