#Documentary Hypothesis and Deuteronomy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Biblical Insights on Personal Revelation and Criticism

Jethro advising Moses (detail), Jan van Bronchorst, 1659. Royal Palace of Amsterdam, Wikimedia The concept of personal revelation is not unique to the faith of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS). It is a foundational principle found throughout religious history, including within the Bible itself. Yet, critics of the LDS faith frequently dismiss or invalidate personal…

#Acts of the Apostles and modern revelation#Biblical context of personal visions#Biblical inerrancy vs. modern revelation#Biblical prophecy vs. LDS doctrine#Biblical support for ongoing revelation#Burning in the bosom LDS explanation#Christian faith and modern revelations#Comparative analysis of Paul and Joseph Smith#Criticism of LDS personal revelation#Cultural context of biblical revelation#Dead Sea Scrolls biblical accuracy#Deuteronomic reform and scripture#Dissecting evangelical criticism of LDS faith#Divine personal revelation examples#Documentary Hypothesis and Deuteronomy#Faith and biblical textual variants#Faith-building scriptures for Christians#Historical transmission of biblical texts#Holy Spirit guidance scripture#Holy Spirit in John 16:13#Isaiah 40:8 analysis#Joseph Smith First Vision accounts#LDS teachings on the Holy Spirit#Life After Ministry blog analysis#Mormon views on scripture and revelation#Personal revelation in Christianity#Prophecy in Joel 2:28-32#Redaction in Genesis flood narrative#Reproof and guidance by Holy Spirit#Road to Emmaus burning hearts

0 notes

Photo

Samuel

Samuel is a character in the Hebrew Bible and the Old Testament, uniquely depicted as having served several roles, as judge, military leader, seer, prophet, kingmaker, priestly official, and loyal servant of Yahweh. He is traditionally thought to have played a pivotal role in ancient Israel's transition from the judges to the monarchy.

Authorship

Of the many ways the story of Samuel in the Bible is viewed, Tony Cartledge suggests, "While putting more or less trust in the veracity of the materials, the reader must approach the text on at least two levels: as story and as history" (13). Based on 1 Chronicles 29:29-30, the books of Samuel in the Old Testament are traditionally thought to have been primarily authored by the person Samuel, "with supplementary information about the period following his death being supplied by the prophets Nathan and Gad" (13).

However, modern scholarship provides another view. When the particulars of purported accounts of historical events diverge, this suggests multiple authors or sources. For example, in the flood story in Genesis, one version has Noah gathering one pair of each kind of animal; another has him gathering seven pairs of clean animals and one pair of unclean animals; in one account, Noah sends out a dove; in another, he sends out a raven; in one version the flood lasts a year; in another 40 days and 40 nights, and so on. The Bible is replete with such instances. That is an indication, as Richard Friedman says, "of a skillful redactor capable of combining and organizing separate documents into a single work that was united enough to be readable as a continuous narrative" (60). After all, someone somewhere brought the compilation of material we know as the Bible to its final version.

As the Hebrew Bible has been translated largely through the Masoretic Text and Greek Septuagint, in modern times, the source-critical view of authorship has come to play a prominent role in the historiography of the Bible. Building on the works of others, German biblical scholar Julius Wellhausen (1844-1918) brought what has come to be known as the "documentary hypothesis" of authorship into a more thorough form. According to Wellhausen, for the first five books of the Bible, known as the Pentateuch, an editor had at his disposal the works of four authors of different classes, writing at three different stages of Hebraic religious evolution. The earlier J (Jehovah) and E (Elohim) sources "reflected the nature/fertility stage of religion. Writing later, D (Deuteronomy) reflected the spiritual/ethical stage, and P derived from the priestly/legal stage" (Friedman 24-26). While many other aspects of Wellhausen's work have been criticized, the idea of redaction of multiple sources remains the basis for source-critical methodology.

A second seminal and more recent contribution comes from Martin Noth (1902-1968). His Deuteronomist history postulates that the books of Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, 1-2 Samuel, 1-2 Chronicles, and 1-2 Kings were all "the work of a single writer working in the exilic period, who organized the various old units and complexes of material available to him into a continuous history of Israel from the entry into Canaan until the beginning of the exile" (McCarter, 4). Considering style, language, and thematic similarities to Deuteronomy, Noth identifies the writer of Deuteronomy, with the interests of P, as the sole compiler and editor of the books of Joshua to 2 Kings.

However, with a revision, Frank Moore Cross (1921-2012) places a primary edition (Dtr¹) to the pre-exilic time of king Josiah with a secondary touched-up version (Dtr²) completed during exile. Finally, Richard E. Friedman postulates that Dtr¹ and Dtr² were the sole collaborative works of the prophet Jeremiah and his scribe Baruch, as they fit the bill of P and were alive during Josiah's reign and were together in exile in Egypt.

Concerning Samuel as part of Deuteronomist history, several divergences suggesting multiple authors are pointed out.

Besides the twice-mentioned death of Saul (1 Sam 31; 2 Sam 1), there are other duplicate versions of the same events. Eli is twice warned that his priestly dynasty will fall (1 Sam 2:27-36; 3:11-14). There are two accounts of Saul's public acclamation as king (10:17-24) and two of his rejection (13:14; 15:23). When David flees from Saul, he is twice betrayed by the Ziphites. (Cartledge, 4)

Then there are hard-to-reconcile accounts, as in 16:14-23, where David becomes Saul's personal musician and assistant, yet in the next chapter, when David offers to fight Goliath, he is unknown to Saul. Then there is the antagonism towards the monarchy in 7:1-8:22, but in chapters 9-11, a seeming vote for it "as a means of divine deliverance" (Cartledge, 4). Moreover, there are stand-alone sections such as Hannah's Song, the Ark Narrative, and the Court History of David, where there is no mention of Samuel though in other places he is purported to have vetted and anointed the king.

There remains a lack of consensus as to when excerpts were written and collated, the number and level of completion of the sources received, and if there were one, two, or a school of editors. Regardless, the seriousness and respect with which the source materials were handled are reflected in the fact that divergent narratives were maintained, even though it might have been tempting for the sake of a stronger appearance of historicity to delete countervailing ones.

Moreover, while the source-critical method of the historiography of the Bible has maintained the lion's share of attention within scholastic circles for some time, in recent times, literary criticism and inquiry into the social world of the Bible are making important contributions. Archaeological finds are also having their impact. The Zayit Stone, discovered in 2005 and dating to the 10th century BCE, inscribed with the Old Hebrew alphabet, may, for some, moderate the position of a narrative built on eons of oral tradition. It appears the Hebrews were literate early on, which may shed new light on source material considerations. Friedman's theory that Baruch was the final author of Deuteronomist history is strengthened by the Baruch stamp find, which shows that a person named Baruch lived and was a scribe at that time. The Aramaic inscription bytdwd from Tell Dan recently discovered by Avraham Biran and J. Naveh, as it is thought to be translated as "House of David," confirms for some the historicity of king David and lends credit to the stories surrounding him and those such as Samuel, associated with him.

Nonetheless, as Cartledge shares, camps for and against the historicity of the Old Testament are divided into the minimalist approach "of the Alt-Noth school who argue that scientific historiography cannot simply accept the Old Testament at face value" and the maximalists "from the Albright-Bright circle who believe the Old Testament documents are more trustworthy and while acknowledging discrepancies, may be used to reconstruct the history of ancient Israel" (9). As part of that history, the story of Samuel is one of transition between the period of the judges and the monarchy. Portrayed to have facilitated that passage, Samuel is shown serving several leadership roles.

Continue reading...

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

i think the thing is that the bible is not "one document" in the same unitarian way as e.g. the quran is or the homeric poems are, even looking at just the jewish bible or just the christian new testament it's actually a combination of different documents, and the process of separating these out and analyzing them and seeing how they fit together or why they were arranged in the way that they were is potentially interesting to anyone who is into philology and hermeneutics.

Now, the often-cited "Documentary Hypothesis" for the torah is probably wrong in the specifics, which I feel obligated to point out at the outset, the idea that there are four coherent texts within the extant torah that all originally circulated independently does not bear scrutiny. but it was a step in the right direction as far as seeing the text as an accretion text that was redacted over several centuries; there certainly are many different documents that went into the compilation of the torah, off the top of my head, the first 10 to 11 chapters of genesis are probably a later addition, which contains two different noah stories woven together; there's two different law codes in Leviticus, exodus is a mixture of several different law codes and commentaries on festivals with a probably separate narrative weaving them together, Numbers has a lot of commentaries on different laws in the form of stories and probably consists of all the longer fragments and stories the compilers wanted to tell that didn't fit into the earlier books neatly.

Many scholars have recognized that Deuteronomy probably belongs with the first few books of the prophets, i.e. Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings. Once you group these books all together you can analyze them as a continuous whole, and see the different fragments that went into the composition of this set of "books" such as the narrative struggle between Elijah/Elisha and Jezebel, the story of David and Absalom, the narrative of the construction of the temple, the folk tales of heroes that were compiled into the book of "Judges" etc.

And similar with the latter prophets, etc.

And the Christian books are their own beast, the three "synoptic" gospels not only retell the same story but in fact use nearly identical language to tell that story, and figuring out how the three texts relate to each other and what other texts were circulating at the time that influenced them in the form we have today is one of the most interesting puzzles to be solved, though of course there will never be any definitive solution. There's also the matter of how these books group together, where Luke, Acts and the letters attributed to Paul probably circulated on their own together even if they were written at different times, John probably circulated with the "Johannine" letters and revelation, etc.

And basically once you have all these texts separated out into a plausible arrangement, then you can ask the same sorts of questions about historical relevance and countertexts and whatnot that you get from the Quran or Homer or Plato, though of course your own conclusions might differ wildly from someone who sees the texts as being arranged somewhat differently. If you're looking for something more definite and less philological you could also always look the other direction in time and see how these books were read after they reached something close to the form we have them, as there's no shortage of surviving commentary/exegesis/etc in both Jewish and Christian traditions.

tl;dr: the bible is the OG philological text, most of the modern field of philology grew out of biblical studies, if you like philology and know Greek and/or Hebrew it's something you can delve into fractally

I just don't find the Bible to be a very interesting document. It's more interesting for what was built on it later, right, I think the centuries of Christian and Jewish thinking are somewhat interesting. And Islam is very interesting. But the Bible itself is kind of... I think my deal is it's not poetry, it's prose and not poetry, which sucks major ass. And it's not tantalizingly ancient like Gilgamesh, it's just kind of a bog standard Iron Age old book of stories. I don't know. I think Homer is cooler.

But the Bible is probably more intensely analyzed than like any other text ever, so I kind of wish I was Biblepilled. Anyone want to Biblepill me? Why is the Bible a cool book to read? Why is the Bible neat?

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think my mistake in Jewish study groups is always assuming that everyone else is way more down with the documentary hypothesis of the authorship of the Torah than they actually are, so I’ll say something about something being reinterpreted between Exodus and Deuteronomy because in my head I’m thinking about the Deuteronomic historian, but then my very nice rabbi will go, “Well, I wouldn’t go so far as saying the Torah interprets itself! That’s our job” and I’m just like 🧍🏼♀️ duh Kyra this is not a history class

#deuteronomic historian my beloved……..#but i know i need to Stop#i just. forget. i don’t know#the documentary hypothesis means so much to me#to me the editing the redacting the piecing together of the torah: it’s an act of love#but i know it’s like. a bit blasphemous?#anyway#personal#torah study

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Venom Fire I took some time away to hear from the Lord. I needed some clarity on questions I had concerning people who have received the Covid vaccine. I spent time in prayer for answers and part of this teaching is what the Lord gave me. He showed me the things that have come to light about the vaccine “Remdesivir.”

We did an interview with Dr. Brian Ardis, who recently came out with a documentary - his hypothesis is that Covid 19 came from snake venom that is found in our water. As I was listening to Dr. Brian something was telling me to look more into it. The Lord would not let this get out of my mind. There were things that the Lord started to unfold for me and I began to see in the Word how this was happening, and how these events were foretold.

Let’s keep in mind that serpents don’t always represent evil. Jesus said to be wise as serpents, and in Genesis it says that the serpent was the wisest among all the beasts. There are two types of wisdom: the wisdom of God hidden in a mystery, and the wisdom of man that is coming to nothing. When Moses and Aaron faced Pharaoh’s magicians and their rods turned into serpents, it was a battle of Wisdom. God’s wisdom consumes the wisdom of man like the serpent consuming the serpents, or rods, of Pharaoh’s magicians.

In the book of Deuteronomy, the Lord establishes how He is the Rock, which is Christ, who provided them their escape from the bondage of Egypt. He provided them with manna, which the early church taught are the mysteries of the kingdom. They became ungrateful and began to murmur against God and Moses about the manna. This represents people who become ungrateful and complain about the mysteries of the kingdom that are being taught, just like the religious people who complained about the teachings of Jesus. The Lord does not care for those who have a murmuring spirit.

In response to rejecting His Word, God sends the poison of fiery serpents. The Hebrew word for fiery serpent is seraphim - these were fallen seraphim. Paul says that Satan parades himself as an angel of light, as well as his ministers. Now what happened to Israel was a shadow of what was to come. Paul says that we are the true Jews circumcised in our hearts and not after the manner of flesh. This is what is happening now because the church has rejected the mysteries of the kingdom that Jesus came to teach and they’d rather go back to old time religion.

The Apostle Paul said that at the end they would no longer have a love for the truth, that they would no longer endure sound doctrine but heap for themselves teachers, or venomous serpents. John the Baptist rebukes the Pharisees calling them a brood of vipers. Both John and Jesus call the religious teachers of their time venomous serpents. These false teachers are a pestilence that spew venomous teachings. Paul warns the church to guard their minds from being deceived the way Eve was deceived by the serpent.

Dr. Brian Ardis believes the snake venom was released into our drinking water and that this is the reason for the spread Covid 19. The prophet Jeremiah says that because of His people departing from His Word and being disobedient to His voice he will give them gall to drink. Gall speaks of venom in the Hebrew. In the Book of Revelation, it says that a third of the water will become poisoned. It also says that the serpent will spew water from its mouth to try to destroy the woman in the wilderness, which represents the church. Since when does a serpent spew water from its mouth?

I can see how Dr. Ardis hypotheses ties in with biblical prophecy. I know this is gloomy but there is still hope. It’s important to understand that the Covid shots are not really vaccines - they’re actually gene therapy, which is intended to alter the DNA. The Lord instructed Moses to make a fiery serpent to put on his rod so that all those who have been bitten by the venomous serpents would be healed. The enemy has his seraphim, but the Lord has also His. In the early church, the seraphim represented the keepers of divine knowledge. Jesus is depicted as a seraph, a fiery one, a burning one. The Lord also says that His ministers are a flaming fire.

The Lord was telling me that there is still hope for those who have taken this vaccine. Those who will look and believe the words of his ministers of flaming fire will be healed. The woman with the issue of blood had the faith to reach out and be healed by touching the hem of His garment. This will be the same for those who look on the Lord’s seraphim, his Apostolic and prophetic ministers of mysteries. Amen.

Sincerely, Apostle Michael Petro

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you know of any scholarly works defending traditional Pentateuchal authorship (or at the very least the view that there was just one author) against the documentary hypothesis?

It depends on what one means by “scholarly works.” In my view, the real path to making this case is simply to study the Torah according to its internal literary unity. When one understands why the texts are written as they are, the notion that it is a pastiche of contradictory versions of the same story becomes utterly ludicrous. Here’s an example: in Exodus 19, Moses is said to “go up” after he has already ascended the mountain. It has become something of a trope among source critics to identify this as a literary seam because of its repetition. Such a trope reveals how poorly such critics actually understand these texts. Anyone with the slightest awareness of the grammar of biblical symbolism instantly understands why Moses ascends twice: the holy mountain is geographically marked out with the same pattern that the tabernacle and temple is. The bottom of the mountain is the courtyard. Then midway up there is the Holy Place, corresponding to our starry Heaven. On the top of the mountain, where God’s glory dwells, is the Holy of Holies. When the seventy elders ascend to the midpoint of the mountain, they behold the God of Israel with blue light under His feet- i.e. the sky in daylight.

I would recommend John Sailhamer’s The Pentateuch as Narrative and The Meaning of the Pentateuch for a systematic approach to studying the Torah as a unified work with its thematic center in Jesus Christ. I do not at all agree with his interpretation of the purpose of the law, but his work is very useful both in its explicit engagement with source criticism and self-awareness about method.

I would recommend listening to James B. Jordan’s lengthy series of lectures on the Book of Exodus for a deep dive into how to study the Pentateuch.

https://www.wordmp3.com/speakers/profile.aspx?id=33

Do not buy the lecture-series individually: the best deal will come from buying all of Jordan at once. If you are a serious student of the Bible, it is worth every penny.

Also clearly vindicating the unity of the text is the numerical structures woven through its entirety which depend on the number of letters and words being as they are. Many examples and further resources are presented in this wonderful book:

https://www.labuschagne.nl/z%26oz/Numerical_secrets_2008.pdf

From an historical point of view, perhaps the strongest association that can be made with the Mosaic age comes from an analysis of the archaic literary form in the Book of Deuteronomy. As Kenneth Kitchen demonstrates in an exhaustive study of the subject, Deuteronomy fits into the earlier covenant pattern and not the later. Setting aside matters of chronological revision for the moment (as we are discussing the secular, critical model for biblical origins which assumes the conventional chronology), the conventional model of Deuteronomy as a 7th century forgery is flatly and decisively contradicted by its lack of conformance to the Assyrian-type treaty structure and its precise harmony with the earlier (Mosaic period) structure which had entirely fallen out of use as far as our literary sources from the ANE and Egypt (which are relatively abundant) by the time of King Josiah where the text is supposed to have been forged.

Source critics usually make their errors in the realm of logic rather than history. Comparisons between Deuteronomy and the Assyrian-type treaty are presented with great fanfare. Yet, there is no analysis of whether these parallels are also present in the earlier treaty form. If the feature is present in both early and late forms, it can be used as an argument for neither. Eventually, to be honest, I just stopped taking source critics very seriously as potential sources of information. If you are interested in Kitchen’s analysis, see here:

https://www.amazon.com/Treaty-Covenant-Ancient-Near-East/dp/3447067268

When Deuteronomy is firmly placed in the era of Moses, its literary unity with the first four books of the Pentateuch places the entire written Torah in that same era.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Torah Authors: Possible Identities

In Who Wrote the Bible?, Richard Elliot Friedman sets out to accomplish two goals: first, to provide a detailed explanation and defense of the Documentary Hypothesis, a theory which claims the Torah is a synthesis of four initially separate and complete texts (identified as J, E, D, and P). The second goal was a little more ambitious; to identify not only the time and place these documents were written, but also to try to use the texts to determine what can be said about the authors as individuals. In his attempts to do this, he does a little more than repeat what the current concensus of scholars believe. He advances theories of his own, and even contradicts some aspects of the mainstream. With that in mind, let’s talk about Friedman’s attempted reconstructions of the Torah’s authors....

The Earliest Pair

The earliest documents complete documents to make up the Torah seem to be the J and E sources, both of which seem to be national histories, parallel narratives written during the time between the schism of the kingdoms of Judah and Israel (~920 BC), and the fall of the Kingdom of Israel (~722 BC). Although both can be relatively dated as earlier than the other texts, it would be difficult to date the texts absolutely to a narrower window than that. Nonetheless, Friedman suggests he is able to do so. The J Source: Called the Jahwist source because the Sacred Name is used for God from the beginning of this text, J is believed by Friedman to be most probably the older of the two. Due to the ambivalent relationship between Jacob and Edom in this source, he dates the text to some time after Edom achieved independence in 848 BC. Friedman supports the theory that these texts are cohesive wholes, believing a single author wrote each, perhaps with small inclusions from other sources. The emphasis on King David, along with political posturing against the Kingdom of Israel, suggests an almost certain Judean origin, probably arising from a member of the royal court. Though most likely a male, the level of narrative focus and sympathy given to female characters in this source may be cause to consider the possibility that J’s author was a woman. The E Source: Called the Elohist source because of its use of the generic designation of “God” (Elohim) for the God of Israel, at least until He reveals His name to Moses. E is, again, considered by Friedman to be the product of a single author, theorized by Friedman to have been written in the last decades of Israel’s existence (~750-722 BC). Though it could have in theory been a totally independent creation, the polemical content found within and the use of a similar formal style may be indicative of the possibility that E was a response to J: the creation of a rival national history meant to legitimize the kingdom of Israel, emulating the regal style of J to give itself an air of respectability. The hostility to Judah and sympathy towards the political system Israel is matched by an equal hostility to the religious system of Israel; this suggests an author who was disadvantaged by the current social reality. Friedman suggests a member of the Levite clans at Shiloh, whose claim to the high priesthood was ended by King Solomon (from Judah), and whose special status was challenged by the new religious altars built in the northern “high places” of Dan and Bethel. The author of this text was almost definitely male, and may have considered himself to be a descendant of Moses based on how much time is dedicated to developing Moses as a character in his story. After the fall of the kingdom of Israel, northern refugees fled to, and eventually assimilated in, Judah. As part of this process of reintegration, the previously separate J and E sources were combined into a single document, JE. This redaction must have occurred after 722, and Friedman speculates (for reasons explained below) the latest date for this redaction to be 687. Together, these texts make up the majority of Genesis, half of Exodus, a portion of Numbers, and a sliver of Deuteronomy.

Reactions to the Earlier Documents

The next two sources are believed to be authored in a priestly milieu whose opinions of JE seem to be on opposite ends of the spectrums. Friedman connects both of these documents, D and P, to a member of the priesthood writing during a time of religious reform. Controversially, Friedman breaks rank with other adherents to the Documentary Hypothesis by dating P to an earlier time than D. Why this is the case will be explained below. The D Source: The Deuteronomist Source gets its name because it is primarily responsible for the Book of Deuteronomy, which is stylistically very different from the rest of the Torah. Interestingly, this radically different style is in fact very similar to the six books that follow Deuteronomy, suggesting that the author may have written all seven as a single cohesive work. This Deuteronomic history clearly uses several sources in creating its narrative, but nonetheless spends those books developing several themes that unrolls as the story progresses, revealing an ideological unity. This book is hostile towards the religious practices of Israel, but frames Josiah as a parallel to Moses and a renewer of the Mosaic covenant. Friedman suggests that this work was originally written during the reign of Josiah, the author seeing the king and his reforms as the final triumph of the henotheistic ideal, placing its composition between 632-609 BC. The final revision, adding Josiah’s death and the fall of Judah, is posited to have been done by the original author sometime after 586. This text recognizes JE as an important work and assumes that its readers are familiar with it: the Deuteronomistic history often alludes to the stories depicted in them. Most controversially, Friedman believes it is a reasonable possibility to attribute D not only to a single pair of authors, but that we even know their names: Jeremiah and his secretary, Baruch. Friedman notes not only Jeremiah’s praises of Josiah, but also similarities in the vocabulary and use of shared symbolism between the Book of Jeremiah and the Deuteronomistic history. Though formed into a single work, D also cites several sources that he uses, and the law code in Deuteronomy may predate him: it’s a work that demands centralization of religious structures without making any reference to Jerusalem, which causes Friedman to suggest Shiloh, a northern religious center already established to be hostile to the new high places, as a possible point of origin. Interestingly, Jeremiah is from Anathoth, a town associated with the same clan of priests as Shiloh. The P Source: Known as the Priestly Source for its association with the Aaronid priests of Jerusalem, P is usually seen as the latest of the four documents. Friedman disagrees, beliving that there is evidence that Jeremiah not only was aware of this work, but was actively hostile to it: he thinks Jeremiah explicitly alluded to the P source in order to invert it. If this is true, and if it is also true that Jeremiah is the author of D, then it stands to reason that P must predate D. For this reason, and because both D and P demand centralization of religious authority, Friedman places P at the earlier period in which such reform and centralization was occuring: the reign of Hezekiah, 715-587 BC. P specifically wants this centralization to occur in Jerusalem (at the Tabernacle), and its specific priesthood: Hezekiah’s reign is also noted for making distinctions between the priests and Levites in general. Friedman suggests that the impetus for this source’s composition was, in fact, the redaction of JE into a singular document. Others have suggested that P is in actuality the final redactor of the Torah, placing Priestly materials within the JE text. They suggest this because the P source lacks parallel narratives to many of those found in JE, which could be in theory because P was always intended to be a complement to JE. Friedman proposes a different theory: that the stories P does not inlude are excluded for ideological reasons. After all, there are narrative parallels between P an JE, with P including details that directly challenge the details of JE. In these stories, Moses often comes across looking worse than he does in JE, while Aaron and his family often come out looking better. It should be pointed out, after all, that the stories conspicuously missing in P often have elements that threaten the priestly class; prophets, sacrifices performed before the establishment of the Aaronic priesthood, and a God who speaks directly to His people. P, in this theory, was made as a more acceptable alternative to JE, a new national narrative meant to replace it. It uses the history of the nation of Israel as justification for their rites by telling it through the lens of the laws and sacrificial regulations. It is meant to assert without a doubt the necessity of the Aaronid priesthood of Jerusalem above all others, and to do that it attempts to rehabilitate Aaron while tempering the image of Moses - who, though national founder and Lawgiver, is nonetheless the ancestor of P’s rivals in Shiloh. And that may explain the suspected hostility of Jeremiah towards P - could Jeremiah 8:8 (How can you say, "We are wise, we have the law of the Lord?" / See, that has been changed into falsehood by the lying pen of the scribes!) be in reference to P?

The Final Redactor

Some time after the Babylonian Exile, when the conflict between P and D was no longer a present reality, someone attempted to reconcile JE, D, an P. This reconciliation led to the Torah, which (along with the Deuteronomistic history) was the earliest canon of Hebrew Scripture. The hostility between the priests of Shiloh and Jerusalem was over - the Persians had granted the Aaronids sole legitimacy in the new Temple, the now indisputed center of Israelite religious life. This final redactor was most certainly an Aaronid priest with sympathies towards P. After all, all five books of the Torah open with a passage originating in P. Genesis is constructed around a skeleton from the P source - the genealogies, from Adam to the sons of Jacob. Exodus’s narrative is likewise structured around the Priestly account. The Aaronids may have become more accepting of the traditions of JE and D during their time in the Babylonian Exile; perhaps the price of a reunification of the Jewish people was a unification of the central texts of disparate Jewish groups. In any event, an Aaronid redactor saw something in JE and D that P did not see, something that made them worth preserving. Friedman can point to one Aaronid priest in the early years after the Exile who had the power and authority to accomplish this, who is associated from Antiquity with the renewal of Mosaic religion, and who is treated as a Lawgiver second only to Moses: Ezra, the priest and central character of the book of the same name. This is the man, or at least someone closely associated with this man, that Friedman identifies as R, the redactor who intricately spliced JE, D, and P into a single flowing narrative.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are some things about Judaism and Christianity that you learned that surprised you? What about polytheistic religions like native american animism, Buddhism, Shinto and Jainism? Zoroastrians? Baha’i? Yazidi?

Anon this is… such an in-depth question! Idek where to begin here. Of all those religions, I have learned the most about Judaism since I stopped being religious. What I knew about Judaism prior to maybe 5 years ago was mostly just what Islam says about Judaism. Meaning, you know, from Adam to Moses, then it skips ahead to David/Solomon/Saul, then there are some brief mentions of Jonah and Ezekiel and that’s really it.

So I didn’t know a lot, and I wasn’t very interested in what I did know tbh. The only reason why I started reading the Bible is bc I wanted to compare it to the Quranic versions of the stories and see how much Mohammed fucked them up. And that was fun but I didn’t bother to look much further into Judaism past that. The Books of Kings and Chronicles, for example, I took one look at them, decided they were boring, and didn’t read them until only a couple of years ago. That’s when I first got into the whole Biblical history thing. I tried reading a book about how the Bible was put together and realized I didn’t know enough about the Bible itself to even begin.

I forced myself to read those four books and then some of the prophet books (side note: all of the female prophets were left out of Islam, I didn’t even know they existed. Damn it Mohammed!!!). And I’m glad I did, because it changed my whole view of the Jewish Bible. It’s a history book!! Like… that’s literally what it’s supposed to be, a (legendary) history of Israel/Judah, and every bad thing that happens to them is ascribed to YHWH getting pissed off at them, but then like my friend and her trash boyfriend he always forgives them and takes them back even tho they just go on to disappoint him again. The Bible is the world’s oldest and greatest self-drag!!!

Once I actually knew the general chronology of the Biblical kings and shit I could actually make my way through this book without getting confused (mostly). Highly recommend this one for beginners btw, there is a PDF online and it’s not overly long.

And damn… I know there’s some debate about certain elements of it like the exact nature of the “documentary hypothesis” but even just focusing on the stuff that people agree upon, I didn’t know any of it before reading this, beyond there being no evidence for the Exodus/the huge kingdom of Solomon etc. I also knew that early Judaism was a system where multiple gods existed but YHWH was just their patron god, but I didn’t fully understand the process in how he got conflated with El and became the god.

More relevant to this topic, though, I didn’t understand the history behind the Bible itself. Deuteronomy being written separately/earlier than the rest and the Bible claiming that it was “found” in the Temple after like 900 years in Josiah’s time… like I had never even heard of Josiah prior to a few years ago and here I am realizing that this bitch perpetrated fraud that would make Linda Taylor proud. Tf. AND, the whole thing with Judah being way, way less developed than Israel, and Israel was actually a multi-ethnic and prosperous society, but then after the Assyrians handed Israel its ass the Judeans were suddenly the top bitch in school and wrote the whole Bible to make their former northern neighbors out to be assholes?? Wow Team Israel tbh.

Then when you get to the time of the Babylonian Exile tho you have to feel a bit bad for the people of Jerusalem, like the Babylonians were uncommonly dickish even for their time and the ppl of the city were clearly traumatized tbh… a lot of the stories in the Bible, especially those believed to have been added only after the exile, make a hell of a lot more sense when you realize the huge changes occurring in Jewish society at the time. The transition from “there are lots of gods but YHWH is our god” to “YHWH is the god” is completely understandable when you realize that people were searching for some explanation as to why they had all been uprooted and thrown out of their homes, and the obvious explanation is that, yet again, they had pissed YHWH the fuck off by worshiping other gods.

I feel like both Christianity and Islam (but especially Islam) try to separate many of Judaism’s better-known stories from the context of ancient Israel/Judah itself, presenting them as more universal stories that apply to everyone, but tbh the whole over-arching story doesn’t work unless you look at it as a history written by and for Jews who were rebuilding their religion and society in a volatile period. I’m reading this rn and it’s relevant to that topic.

It’s truly a damn shame that pretty much like 0% of Muslims have been exposed to any of this tbh? I feel like almost all scholars of Biblical history come from non-Muslim countries. I have more feelings on this subject but let me answer the rest of your question. First of all, Christianity. I read the New Testament in full a couple of years ago as well. It was obviously way easier to read because the Gospels are all different versions of the same story and the rest is just supplementary material, basically. I think the text itself is pleasant and Jesus was a chill dude. I like him. And the whole… sequence of events made much more sense after I’d read the Book of Isaiah and realized that the authors of the Gospels were viewing Jesus in light of those prophecies. Revelation is a fascinating shrooms trip. The Acts of the Apostles were fun to read, but all the letters were just like w/e. More historically interesting (if they’re real) than interesting in terms of content. Though I do think some of the content in them is very nice, idk if people know this but Muslims think Paul was responsible for perverting the (non-existent) “real” Gospel of Jesus and paint him very poorly. But I dunno, the letters seemed fine to me.

Tbh I was surprised to see how different Islam’s version of Christianity/Christian stories is compared to the “real thing”. I don’t even mean his disastrous misconceptions of Christian theology but just like… with the stories Mohammed pulled from the Jewish Bible (and the Talmud–which I also enjoyed flipping through btw, it’s like a bunch of old guys yelling at each other in written form), he gets details wrong but the overall stories are basically the same. But with the Christian stories, barely anything in the Quran is from the Bible. I think I’ve said this before but like 90% of the stuff pulled from Christianity in Islam is about baby Jesus, not adult Jesus, and even that stuff isn’t from the Bible. It’s understandable when you realize that he was listening to these stories, not reading them, and just picked the ones he liked best… which happened to be later texts. That brings me to a subject that is near and dear to my heart:

Apocryphal texts bih. I love this shit, with full sincerity and zero irony. The weirder it gets, the better. I started out just reading the ones that made it into the Quran, like the Life of Adam and Eve, the Infancy Gospels that I’ve mentioned before, and the Testament of Solomon. Then some Gnostic stuff, which I only read because it has the same substitute-crucifixion thing going on as Islam, but WHEW chile the DRUGS these ppl were on while writing this shit…! The Sethians and the Nag Hammadi library produced such treasures of crazy-ass literature. It makes me sad how so much of this stuff is just totally forgotten now that Christianity is mostly just Catholic/Protestant+Orthodox. There were so many sects and people had so many divergent ideas, some more drug-assisted than others probably!! And Middle Eastern Christianity was very diverse even in the 7th century. Some of the stories they produced had such rich lore. My fave right now is this Syriac collection:

I came across this one while looking for the origins of the al-Khidr story in the Quran. There were all sorts of opinions about who he was, bc Mohammed never really gave any details on his life, but Ibn Ishaq recorded an opinion that al-Khidr was the one who buried Adam and Allah granted him long life in return. So I looked for the source of that story and it was the story of Melchizedek in this book. Then I read the whole thing and man this would make for some weird psychedelic series or sth. It’s online, look it over and you’ll see how trippy it is.

Um… anon this is getting rly long tbh so let me sum up my knowledge of Shinto, Native American animism, and Jainism: not much!! Buddhism I have only an intro-level knowledge of, I know the basics but I don’t know more than that. The beliefs of Yazidis I don’t fully understand, but the little I know is pretty cool. From what I understand it’s a blend of pre-Islamic Kurdish religion + early Islamic influence + some other influences thrown in. It’s sad how they’re branded as devil-worshipers or w/e when the story of Melek Taus is actually really interesting and has a good moral and is way, way better than the story of Iblis. I also enjoy Yazidi architecture and that unique ribbed cone top of theirs. I hope they’re able to live on as a community after, uh, recent events.

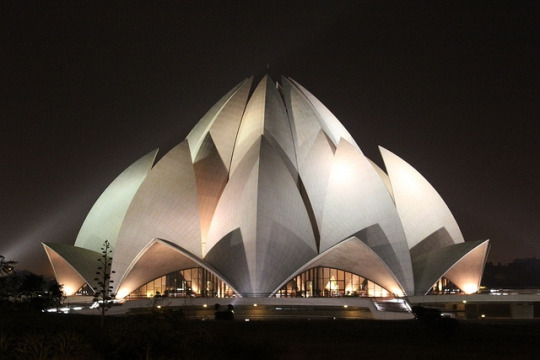

I actually was taught about Bahai people growing up but I was told it was some heretical offshoot of Islam comparable to Ahmadiyya people. I didn’t realize it was considered its own religion until fairly recently tbh. I did read the Kitab al-Aqdas (which is blessedly short, this makes Bahai a great religion automatically!!) once. It’s definitely super inspired by the Quran in terms of style and to me clearly seems to be an attempt to make a Kinder And Also More Iranian Islam. I think it’s pretty neat. In fact I think a lot of attempts to magically make Islam “nicer” would just end up making it more like Bahai tbh. And it has a really fascinating history, with the Bab basically being a new John the Baptist and Bahaullah being the one he foretold. He even accidentally ended up in Israel lmao. I also really love Bahai architecture in terms of how diverse it is, with the only unifying feature being visual interest, and I would love to see the temple in India irl one day. India always has the best architecture anyway.

I saved Zoroastrians for last bc I have to be honest here. I tried to look into it, because it’s ancient and had an influence on Judaism etc and that makes it important. Fam I got about 3% of the way through the Avesta before giving up. I was still in the hymns part and just like… every other word was something I didn’t understand. I will go back and try again one day but for now the answer is “lol idk”.

ANYWAY… yeah… I’ve enjoyed reading about religion way more now that I’m not religious, both in terms of Islam and other religions, I can appreciate the process or w/e now that I’m not constantly trying to make it fit into Islam or panicking every time I spot something that makes me question my faith. I know a lot of atheists either fall away from religion altogether or just look at it like it’s something dumb, but even if it’s fake, that doesn’t make it worthless imo. The history itself is always worth studying.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Should the story of the woman caught in adultery be removed from the Bible? Um, NO, and here is why:

The story of the woman caught in adultery is one of the most powerful historical events to be found in the Gospels. It speaks to the heart of God’s love and mercy, a love that we are to share in our hearts, a love we are to share with the world. It is also a foreshadowing of the gift of grace and salvation to come, a gift won by the physical death and resurrection of Christ, a gift that can bring about our own spiritual resurrection. Who cannot feel compassion as this woman is dragged before the public, an invisible scarlet letter emblazoned on her chest as the religious leaders speak out loud about her sin? Who cannot feel her broken spirit as they mention the Old Testament laws about how those guilty of adultery were to be stoned? And who cannot feel her shock and relief when Jesus states ““Let him who is without sin among you be the first to throw a stone at her.” (John 8:7). Who cannot imagine her exhilaration when Jesus said that he did not condemn her? What a beautiful story of Christ! It is almost impossible to imagine the Gospel of John without it.

And yet, there are many Christians who want it removed from the Gospel of John! I repeat: there are many Christians who want it removed from John’s Gospel! Now why, pray tell, do they want it taken out of the Bible? The following note in the ESV bible offers a clue:

“The earliest manuscripts do not include John 7:53-8:11.” That’s right. The Oldest copies of the Gospel of John that we have do NOT have the story of the woman caught in adultery, which is also called the Pericope Adulterae. Indeed, the earliest copy we have of the Gospel of John that has the story dates from the 5th century AD (though this doesn’t mean that there weren’t earlier copies of John with the passage in it. Not all manuscripts from the ancient world have survived to the modern era. Thus, some may very well have had it. Indeed, there is evidence for this; the Pericope Adulterae made its way into Jerome’s Latin Vulgate Translation in 383 AD, in the 4rth century AD (the year he finished translating the gospels. The Old Testament was translated into Latin from Hebrew by 405). This seems to have been a story that was circulated for a time and then later added to John. Indeed, it is believed by many to have been part of the early Christian oral tradition, just as the rest of the Gospels were before they were put into print. Though many scholars accept that it tells a historical event, its placement in scripture has been a point of debate. Indeed, there was some debate in the ancient world about it as well (more on that later).

So…the Apostle John didn’t write it, its not in the earliest manuscripts of John (i.e. that we have), and therefore, according to many Christian scholars, it should not be considered scripture. Seems like a pretty strong case, doesn’t it? It would be, if it wasn’t for the fact that its based on both the special pleading fallacy (aka double standard) and a refusal to accept the early church father’s testimony about it.

Let’s deal with the latter issue first.

Didymus the Blind, a Christian theologian who lived in the 4rth century, wrote that the story was found in “certain gospels”. It was presented as a historical event in the third century Christian document the Didascalia Apostolorum. Jerome, who translated the bible into Latin (the “Latin Vulgate”) put the story in his translation, even though he acknowledged that it wasn’t found in some versions of John. However, he stated that it was found in many Greek and Latin manuscripts of his day. Augustine was a big supporter of the passage. Indeed, he mentions something quite sinister about Christian leaders who opposed the story in his lifetime: “…certain persons of little faith, or rather enemies of the true faith, fearing I suppose, lest their wives should be given impunity in sinning, removed from their manuscripts the Lord’s act of forgiveness toward the adulteress, as if He who had said, 'sin no more' had granted permission to sin.”

Augustine, De Adulterinis Conjugiis, 2:6–7. Thus, people were removing it from the scriptures.

Is it any wonder, then, that none of the early copies (before the 5th century AD) of John that survived to the modern era don’t have it? Some must have, in order for Jerome to have put it into his translation (remember, he also said there were many Greek copies in his time that contained it).

Now, some have discarded Augustine’s testimony, saying that he also defended the Old Testament Apocrypha (1rst and 2nd Maccabees, Judith, Tobit, Ecclesiasticus, etc.), which are found in the Catholic Bible but not in the protestant bible (save for some King James Bibles). This is a genetic fallacy, a logical fallacy where someone disregards an argument based on its origin instead of on the merit of the argument itself. Yes, Augustine did have some bad theological views, but so did Martin Luther, who started the Protestant Reformation (Luther wrote an anti-Semitic theological book titled “On the Jews and Their Lies”. I guess we should all be Catholic now…). Plus, the fact of the matter is that Augustine actually didn’t consider the apocrypha on par with scripture.

“So what?” the enemies of the Pericope Adulterae will say, “Its still not in the early manuscripts of John! John didn’t write it, therefore it’s not scripture!” Really? Really want to go down that road? Well, then you might as well cut out sections from the Pentateuch as well…

For many ages, Moses was considered the sole author of the Pentateuch aka Torah. Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy were thought to have been entirely pinned by Moses. Then skepticism reared its ugly head, and many scholars rejected the idea of Mosaic authorship, pointing out passages that proved problematic to it (more on them later), as well as repetitions that differed in details and different names of God being used in certain parts of the books (including some areas where Yahweh was used in stories that take place before Moses. The name of Yahweh wasn't revealed to humans until God spoke it to Moses, according to Exodus 6:2-3). This led to the Documentary Hypothesis, the idea that the Torah was written in stages over many centuries, with no parts written by Moses. Eventually, these documents were put together as the Torah.

Interesting idea, but even it has recently come under scrutiny, primarily due to the fact that ancient near eastern literature was known for odd repetitions that at times differed on details (see Paul’s conversion tales in Acts 9, 22 and 26). Individual storytellers and writers in the ancient near east did this, and Moses would have been expected to do the same. Other aspects of the Documentary hypothesis, including the use of different names for God in some passages, likewise fails under closer scrutiny (The passage in Exodus 6:2-3 can be translated to mean that “Yahweh”, as a name for God, was known of long before Moses was born).

Personally, I’ve never accepted the documentary hypothesis, in part due to the fact that there are multiple verses that indicate that Moses wrote a significant amount of the Torah (Ex 17:14, 24:4-8, 34:27, Num 33:2, Dt 31:9, 19, 22, 24). Combined with the fact that most of the material from Exodus to Deuteronomy deals with Moses’ life, as well as the answers to objections about repetitions, differing details and the use of different names of God noted above, one can conclude that a good case can be made for Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch or Torah.

But did he write the entire Torah? Um…Nope.

Genesis 12:6 is our first clue:

“Abram passed through the land to the place at Shechem, to the oak of Moreh. At that time the Canaanites were in the land.” At that time…the Canaanites were in the land. Now, if Moses wrote this, then there is a BIG problem.

You see…the Canaanites were STILL in the land while Moses was alive! The Israelites hadn’t even invaded the land yet (Dt 26:1)! That didn’t happen until after Moses died, when Joshua led the invasion (se Joshua chapters 1-3). Indeed, if you read the book of Joshua closely, chapters 13-18 show that, despite the hyperbolic statement of Joshua 11:23…the land had not been fully conquered. After Joshua died, there were still Canaanites in the land (as shown in Judges chapters 1-2). Indeed, they were still in the land during the time of Ezra, when the Israelites returned to Israel during the time of the Persian Empire (Ezra 9:1)! This happened during the reign of Cyrus the Great of Persia, who conquered Babylon in 539 BC and then gave the Jews permission to go back home.

Cyrus died in 530 BC.

Moses lived about 1400 BC.

Next, let’s look at the Edomite Kings list in Genesis 36:31-39:

“ These are the kings who reigned in the land of Edom, before any king reigned over the Israelites. Bela the son of Beor reigned in Edom, the name of his city being Dinhabah. Bela died, and Jobab the son of Zerah of Bozrah reigned in his place. Jobab died, and Husham of the land of the Temanites reigned in his place. Husham died, and Hadad the son of Bedad, who defeated Midian in the country of Moab, reigned in his place, the name of his city being Avith. Hadad died, and Samlah of Masrekah reigned in his place. Samlah died, and Shaul of Rehoboth on the Euphrates reigned in his place. Shaul died, and Baal-hanan the son of Achbor reigned in his place. Baal-hanan the son of Achbor died, and Hadar reigned in his place, the name of his city being Pau; his wife's name was Mehetabel, the daughter of Matred, daughter of Mezahab.”

Now, did you catch that first verse? Let’s look at it again:

“These are the kings who reigned in the land of Edom, before any king reigned over the Israelites.” (emphasis mine) Moses didn’t write that. How do I know?

Because King Saul, the 1rst King of Israel, didn’t live until centuries after Moses! Heck, his reign marked the end of the Judges period!

Now, to be fair, Abimelech, son of the Israelite Judge Gideon, was made king of Shechem, and ruled Israel for 3 years (Judges 8:30-9:22). However, his kingship wasn’t instituted by God (thus God didn’t recognize it, see Dt 17:14-17). He was an evil king, and during a battle a woman threw a millstone onto his head. Not wanting to die due to a woman, he had his armor bearer run him through with a sword. This was all due to the wrath of God (Judges 9:1-57). Oh, he also lived long after Moses and Joshua.

Now, some may say that there may have been a king who reigned during Moses time, someone who wasn’t mentioned in the Bible. Well if that’s the case (no evidence for it whatsoever), then how do people who believe that explain Deuteronomy 17:14-17:

“When you enter the land the LORD your God is giving you and have taken possession of it and settled in it, and you say, "Let us set a king over us like all the nations around us," be sure to appoint over you a king the LORD your God chooses. He must be from among your fellow Israelites. Do not place a foreigner over you, one who is not an Israelite. The king, moreover, must not acquire great numbers of horses for himself or make the people return to Egypt to get more of them, for the LORD has told you, "You are not to go back that way again." He must not take many wives, or his heart will be led astray. He must not accumulate large amounts of silver and gold.”

Thus, many of the Edomite kings in the Genesis 36 kings list lived long after Moses. Ergo, Moses didn’t write Genesis 36:31.

It’s also safe to say that he didn’t write Deuteronomy 34, which records his death. No one writes their own obituary.

Some try to say that Moses was writing about his upcoming death as a prophecy, but if he did…why did he describe it in the past tense? Indeed, the passage seems even less like a prophecy in verse 10: “And there has not arisen a prophet since in Israel like Moses, whom the LORD knew face to face,” Indeed, in Dt 33:1, right before he gives his final blessing on Israel, it states: “This is the blessing that Moses the man of God pronounced on the Israelites before his death.”

Similar arguments have been made for Genesis 12:6 and 36:31. Some have tried to make the case that both are actually prophecies penned by Moses, the former referring to the eventual removal of the Canaanites, the latter to future Edomite kings and the future Israelite monarchy. However, just like the passages about Moses’ death, they are described in the past tense. There is a reason for that; Genesis is a history, not a prophetic book. True, it does record some prophecies (Genesis 3:15, 15:4-5, 13-16, etc), but Genesis 12:6, 36:31 and Deuteronomy 33:1 and 34:1-12 (Deuteronomy is also a history) are written in the past tense, meaning...that they already happened when these passages were written down. They are no different from the rest of the historical passages in the Torah. They are structured as history, not prophecy. To say otherwise is to commit eisegesis, instead of considering the historical facts of the Bible. Let’s face it: Moses didn’t write these particular passages. Indeed, there are no doubt other parts of the Torah that he also didn’t write. Though Moses wrote the Torah, people added to it over time. Indeed, some of these additions were put in centuries after Moses’s died.

Just like the story of the woman caught in adultery was put into the Gospel of John a few centuries after it was written…

This begs the question; why are the same people who want to cut out John 7:53-8:11 not raising a ruckus about these passages in the Torah that Moses didn’t write? Why the double standard??

I could understand a little if they believed in the Documentary Hypothesis, but the Documentary Hypothesis doesn’t jive with the Biblical evidence for Mosaic authorship seen above. Whether one thinks that Moses wrote a little bit of the Torah, or most of it, there is no denying that some of the Torah was written much later. And yet, the scholars who dismiss John 7:53-8:11…don’t dismiss Genesis 12:6, 36:31, or Deuteronomy 34. I once had a short twitter debate with a Biblical scholar (whose name I won’t mention) over the Pericope Adulterae . When I brought the passages up in the Torah that Moses obviously didn’t write, then asked why he didn’t want them gone because they weren’t written by Moses, yet still wanted John 7:53-8:11 gone, because it wasn’t written by the Apostle John, he said “That’s not how textual criticism works.”

What a way to sugarcoat a Special Pleading Fallacy. Now, some will cry foul, saying that there was controversy over the passage even during the ancient world. Well...guess what? Come on, guess what?

There was also controversy over Jude, James, Hebrews, the Book of Revelation, 2 Peter and 2 and 3rdd John! Indeed, in the third century, these (and several other NT works) were at times excluded from scripture! Though there was already recognition of some NT books being canon in the 1rst century (2 Peter 3:16) it wasn’t until 367 AD that the New Testament canon acquired its current form. Folks, Textual criticism is an interesting field of study. To see what was originally in a historical document and then dismissing what’s not can be comparable to a surgeon removing a tumor from a body. But we also have to remember that God is the ultimate author of the Bible, inspiring John, Moses and countless others to write these sacred treasures. The story of the woman caught in adultery is no different. To remove it from the Bible would be like a surgeon removing a healthy organ from a body. Like Jude and the book of Revelation, this passage passed the test of the ancient church and later the reformation (when the Old Testament Apocrypha was removed). It speaks to the character of Christ, whose life perfectly reflected the truth that God is love (1 John 4:8,16).

Sources:

“Nelson’s Dictionary of Christianity” by George Thomas Kurian (Editor), 128-29 “Encountering the Old Testament” by Bill T. Arnold and Bryan E. Beyer, 168-169 “The Apologetics Study Bible (Holman CSB), 1587 “Archeological Study Bible (NIV)”, 15 “Oxford Guide to the Bible” by Bruce M. Metzger and Michael D. Coogan (Editors), 102-104

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Vulgate

https://www.bibleodyssey.org/en/passages/main-articles/woman-caught-in-adultery

https://confessionalbibliology.com/2016/03/29/response-to-james-white-on-augustine-and-the-pericope-adulterae/

https://purelypresbyterian.com/2016/12/01/defense-of-the-pericope-adulterae/

https://www.ancient.eu/Cyrus_the_Great/

https://www.ancient.eu/Moses/

https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/martin-luther-quot-the-jews-and-their-lies-quot

https://www.christiancentury.org/article/critical-essay/on-luther-and-lies

https://www.logicallyfallacious.com/logicalfallacies/Special-Pleading

https://yourlogicalfallacyis.com/special-pleading

https://www.logicallyfallacious.com/logicalfallacies/Genetic-Fallacy

https://yourlogicalfallacyis.com/genetic

http://textualcriticism.scienceontheweb.net/FATHERS/Augustine2.html

0 notes

Photo

Book of Genesis

The Book of Genesis is the first book of the Jewish scriptures and the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. Genesis takes its name from the opening line in Hebrew – beresit, ("in the beginning") – later translated into Greek as genesis ("origin"). Genesis is the first text of what eventually became designated the Pentateuch, the Jewish Torah ("teachings"): five books of the Laws of Moses.

The Documentary Hypothesis

Genesis consists of a variety of literary details: myth, hymns, prayers, sacrifices, rituals, oracles, folk tales, and historical narratives. Tradition claimed that the first five books were written down by Moses, who passed them to his general Joshua when the Israelites arrived in Canaan from Egypt. In the 19th century, the social science disciplines of archaeology, anthropology, and sociology emerged and were utilized to study ancient civilizations and ancient texts. What is noteworthy in Genesis is that several of the stories are repeated, but with varying details. At times, the God of Israel is referred to as "Lord," but at other times as "God almighty." When this occurs we also find theological differences, as well as indications of changing historical contexts that included politics.

After the period of the united monarchy under King David and his son, Solomon (c. 900 BCE), two separate kingdoms were created: the Northern Kingdom of Israel and the South Kingdom of Judah. A way to explain the formation of the text was proposed by Julius Wellhausen (1844-1918), who taught at the University of Göttingen in Germany, in what became known as the Documentary Hypothesis. As we do not know who actually wrote the biblical texts, the various elements were assigned to a source:

J, the Jahwist, or Jerusalem source The Hebrew name of God (revealed in the book of Exodus) consisted of four consonants, YHWH ("I am that I am"), described as the tetragrammaton. We have the German J, for the pronouncement of the Y sound. The later Masoretic version added vowels, which gives us the English version, Jehovah (which does not appear in the Bible). The J source utilized anthropomorphic portraits of God; "the face of God," "the hand of God." In these texts, God often visits the earth.

E, the Elohim source The E comes from a form of the Canaanite el, pluralized as representing several aspects of the godhead, but also from the tribe of Ephraim, settled in the Northern Kingdom of Israel. The E source portrays God as a more abstract being who does not come to earth, but communicates through angels.

P, the Priestly source The P source is a collective term for priestly concerns. This includes the sacrifices, rituals, hymns, prayers, and the begats of Genesis. The Hebrew begat ("brought forth") was the term for procreation. All ancient cultures emphasized bloodlines in detailed genealogies. This validated concepts and practices handed down through the generations. In oral cultures, the repeated lists of the begats may have been a way to memorize oral traditions.

D, the Deuteronomist source This source was named after the last of the five books assigned to Moses (Deuteronomy). It is a collective term for the final form of the traditions that were written down. In 722 BCE, the Neo-Assyrian Empire invaded the Northern Kingdom, and refugees from the North migrated to Judah. This may be when northern traditions were first joined to southern traditions, combining the J and E sources.

In 587 BCE, the Babylonian Empire invaded Judah and destroyed the Temple of Solomon. At that time, some Jews were taken captive to the city of Babylon. This period is known as the Babylonian exile." The theory is that the "Deuteronomist," either a person or school of scribes, completed the final redaction, or editing, of all the combined sources while in Babylon, beginning c. 600 BCE, but with further editing over the next several centuries (in a range from 538-332 BCE).

Jews Mourning the Exile in Babylon

Eduard Bendemann (CC BY-SA)

Continue reading...

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

“who wrote the bible?” by richard elliott friedman

i liked it! it was written at a very very introductory level, and it was careful not to step on any Judeo-Christian toes in the process of explaining the process by which the half of the tanakh up to the end of 2 kings was written, but it was a very thorough explanation of the documentary hypothesis and how we know where their authors came from and so on

he also says that deuteronomy and joshua through 2 kings were almost certainly probably written by the prophet jeremiah (or possibly his scribe baruch, for whom we have definite archaeological evidence), and that all the sources were ultimately compiled by ezra the priest

but the used copy i bought on amazon came from someone who had taken a thick pen and a ruler and underlined at least a paragraph per page in perfectly parallel, except for sometimes when they lined up the ruler at a completely blank point on the page, including one time when they drew a line over the edge of the rest of the pages in the book

it’s like it was formerly owned by a robot

0 notes

Text

Reverend Moon and Jehovah vs. Jesus and God

'From the providence of restoration, there must be a lady who proclaims herself as the wife of Jehovah. Without finding this lady the providence cannot be carried on. Therefore he [Moon - ed.] looked for such a lady. So in South Korea he visited every religious group and all prominent ministers to find such a lady…. At that time there were many people who went between South Korea and North Korea, and he found out that there was a lady who was claiming herself to be the wife of Jehovah' History Of Unification Church Reverend Sun Myung Moon December 27, 1971

'The woman was called Grandmother Pak. She represented both restored Eve and Eve immediately after the Fall, so she was representing two divergent realities. She had flexible capacity; God sometimes entered her to perform His work, and Satan would also sometimes enter her to perform his work. ...I took the position of a mere child who did not know anything and served that grandmother with my heart and my life.' Sun Myung Moon’s Life In His Own Words

' Israel is the tribe of his inheritance: Jehovah of hosts is his name. Thou art my battle-axe and weapons of war: and with thee will I break in pieces the nations; and with thee will I destroy kingdoms; ... And they shall be desolate for ever, saith Jehovah.' Jer 51:19-26 ASV

If we interpret the Bible literally, regarding it as an infallible historical document, we are eventually confronted with a contradiction between our personal ideal of goodness and the so called 'goodness' of the 'God' of the Bible who, by his own admission, is jealous, wrathful and full of vengeance. The fear of the 'Lord' is constantly stressed throughout the Old Testament. He is expected to reward those who worship him and are not delinquent in their observance of the ritual law, by gratifying their worldly desires for material gains and worldly power. This cruel, bloodthirsty, and selfish 'God' is Yahweh (Jehovah) , who, as the historian Gibbon observed in 'The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire', is a 'being liable to passion and error, capricious in his favour, implacable in his resentment, meanly jealous of his superstitious worship, and confining his partial providence to a single [Jewish] people and to this transitory life.'

Scholarly research indicates that the Hebrew Bible, far from being an infallible historical text authored by the Supreme Being, is a heavily revised compilation* of at least two entirely separate works. Fused together in the Book of Genesis are two separate works known to scholars as the northern 'E' and southern 'J' traditions, which are supplemented by additional revisions and inserts. In 'E' (the Elohist passages) exists the pre-Judean tradition of the northern tribes of Joseph who exalted the Most High God El and His subordinate Elohim (angels). The 'J' or 'Jehovist' passages of Judah describe a totally alien entity, the morally deficient and belligerent Jehovah (YHWH), the 'Lord'. According to Max Dimont in 'Jews, God and History': 'In the 5th century B.C., Jewish priests combined portions of the 'J' and 'E' documents, adding a little handiwork of their own (known as the pious fraud), which are referred to as the 'JE' documents, since God in these passages is referred to as 'Jehovah Elohim' (translated as 'Lord God').' This is why within the Bible we encounter contradictory and conflicting images of God. First, we find the Most High God who created man and the universe in goodness. Later, we find the malevolent Yahweh, an angel, masquerading as the Supreme Being. The early Hebrews knew Yahweh as only one of many elohim. They distinguished between the Most High and the angel Yahweh as follows:

'When the Most High divided the nations, when He separated the sons of Adam, He set the bounds of the nations according to the number of the angels of God. And His people Jacob became the portion of Yahweh, Israel was the line of His inheritance.' ** Deuteronomy 32:8-9 Brenton's Septuagint

The spiritual Christians of the early centuries AD, who preserved the original teachings of Jesus, distinguished between the Heavenly Father and the god of the Hebrew Bible. Yahweh (YHWH) was not the Father revealed by Jesus. The Hebrew Bible revealed a tribal god who compels his tribe to force all other non Jewish [i.e. 'gentile'] tribes into submission. The God of Jesus was the universal Father of all humanity. The Hebrew god was a god of fear. Jesus' Heavenly Father was a God of love. In fact, Jesus never referred to the Heavenly Father as Yahweh. The Hebrews were under the delusion that they knew the Most High God, but they were ignorant of Him, and knew only a false god, an impostor, whose true nature was largely a mystery to all but the maniacal priests and rabbis who hid their deepest beliefs in the Talmud and Kabbalah.

Like the Hebrew Bible, reverend Moon's theology is a combination of disparate and conflicting doctrines. The publicly presented divine principle is a legitimate, biblically supported teaching about God, sin and the mission of Christ. Although not in strict accordance with current conventional Christian thought, it is in line with the core of Christian truth which is the absolute necessity of salvation through Christ. It differs from the conventional weak kneed Pauline Christianity in key particulars regarding the return of Christ and Christian responsibility at that time. But its position is no less biblically supported, if not more so, and it is intuitively more appealing to our logical sensibilities.

But it turns out that reverend Moon does not adhere to divine principle in thought or practice. In word and deed Moon adheres to the Babylonian mystery religion sex magic of 'divinely authorized' illicit 'providential' sex as practiced by Judah and his descendants in the kingly line of David as well as the wife of Jehovah mentioned earlier.

We see that after two millennia Yahweh returned to Jerusalem in 1947 at which time he began immediately working to 'break in pieces' the enemy nations of Zion in the Middle East. However, Moon has said that Korea had inherited the messianic mission of Israel. If that's so, does it mean that having failed to fulfill the messianic blessing of the God of Israel, Korea had to then inherit the curse of Judah and its god Jehovah before he returned to Zion? 'Almost every house in South Korea has a translated Talmud. But unlike Israel, even Korean mothers study it and read from it to their young children. ...in a country of almost 49 million people, many of whom believe in Buddhism and Christianity, there are more people who read the Talmud – or at least have a copy of it at home – than in the Jewish state. Much more.'

'Israel is the tribe of his inheritance: Jehovah of hosts is his name. Thou art my battle-axe and weapons of war: and with thee will I break in pieces the nations; and with thee will I destroy kingdoms; And I will render unto to all the inhabitants of Chaldea all their evil that they have done in Zion saith Jehovah.... And they shall be desolate for ever, saith Jehovah.' Jer 51:19-26 ASV

------------------------------

*All introductions to the Old Testament published throughout the twentieth century contained in some form or another the Documentary Hypothesis, which stated that the Pentateuch was a composite of (at least) four sources: the Yahwist (J), Elohist (E), Deuteronomist (D) and Priestly (P) writers. The existence of the Yahwist and Elohist writers, whose separate identities are discernible from the difference in their name for God —Yahweh and Elohim—, was able to explain the book of Genesis’ duplicate narratives, discordant chronologies, and contradictions. The Deuteronomist source of the Deuteronomic law code is differentiated by its very different theological tone, message, unique style and vocabulary, as is the Priestly source by its emphasis on cult, ritual law, and genealogies. These sources could be identified and arranged in chronological order according to their theological, linguistic, and historical emphases.

Their final form came about through a series of redactional stages that dovetailed these sources together. J (Yahwist) was dated to the Solomonic era (9th c. BC), or a century afterwards, and seems to have been a product of the Judean scribes of the southern kingdom. E (Elohist) was seen as a literary product of the northern kingdom and therefore must have been composed prior to its fall in 722 BC. J and E were redacted together probably not much later than the fall of Israel. To the composite JE text, D (Deuteronomist) was combined, which most probably occurred sometime in the 5th century BC. A further redactional process probably occurring in the 5th or early 4th century BC added the post-exilic composition P (Priestly) to this JED document.

**The Septuagint translators plainly understood that the 'sons of God' (beney 'elohim) spoken of in Deuteronomy 32:8 and elsewhere were spirit beings ('angels'), and rendered it that way several times (Job 1:6; 2:1; 38:7) in order to clarify the meaning.

0 notes

Text

Did Moses Write the Torah? Yes and No…

From the dark recesses of antiquity to the 1600’s, scholars accepted that the Pentateuch or Torah was written by Moses, the great Hebrew lawgiver. Though skepticism about the idea emerged in the Dark Ages, it was nevertheless the consensus among both historians and theologians for many a century. However, skepticism grew, until eventually the theory of Mosaic authorship of the Torah was discarded. There were several reasons for this, including the fact that Deuteronomy recorded Moses death and burial (Deuteronomy 34:5-12). Scholars also argued that the Torah was laced with repetitions and contradictions. One of these so-called contradictions was God’s statement to Moses in Exodus 6:2-3 that he had not revealed his name “YWHW” (Translated “LORD”) to Abraham, even though Abraham calls God “YWHW” in Genesis 14:22. Indeed, the name of God alternates in the Torah, at times being “Elohim” and at other times “YWHW”. Eventually, this led to a new theory of the origin of the Torah, one called “The Documentary Hypothesis”. The Documentary Hypothesis states that the Torah was written in four parts at four different points of history. These four documents are called J (Yahwist, because it used YWHW as God’s name), E (Elohist, because it uses Elohim as God’s name), D (Deuteronomy) and P (The Priestly Source, which includes a lot of ritual material as well as narrative). J is the oldest, dating to about 950 BC (about the time of David and Solomon), while E was written a hundred years later or more. D was written about 621-22 BC, while P was written about 500 BC. In 750 BC, J and E were combined as one text. In 600 BC D was added to them, and by 450 P was added to them as well, becoming the Torah. Considering that Moses would have lived around 1400 BC, this would mean that he didn’t write any part of the Torah. The Torah would be in this regard a Pseudepigrapha (“False ascribed to”), a kind of ancient book that falsely ascribed authorship to a famous religious figure (The Books of Enoch being big examples).