#Doctrine and Covenants application

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Hearken, O Ye People: A Call to Repent and Return to the Lord

“Hearken, O ye people” isn’t just an invitation—it’s a command from the Lord. Doctrine and Covenants 1 is His call to review our hearts, repent, and recommit to His covenant. Given as the preface to the revelations of this dispensation, this section emphasizes the urgency of listening to His voice and aligning our lives with His will. It’s not just for the early Saints; it’s for all of us today.…

#Apostasy in the Latter-days#Biblical parallels to Doctrine and Covenants 1 warnings#Book of Commandments history#Challenges of cultural drift from Christ-centered values#Christ-centered living in modern society#Doctrine and Covenants 1 study guide#Doctrine and Covenants application#Encouraging repentance through Latter-day Saint teachings#Faith and cultural shifts#Hearken and obey the Lord#How to apply Doctrine and Covenants in daily life#How to strengthen faith in a Christ-centered way#Joseph Smith revelations insights#Latter-day Saint teachings on obedience#Lessons from Doctrine and Covenants for modern Christians#Modern apostasy and repentance#Preface to Doctrine and Covenants#Prophetic counsel and warnings#Repentance and returning to Christ#Share the gospel through social media#Spiritual growth through scripture study#Strengthen faith with scripture study#Understanding apostasy in the Doctrine and Covenants#Voice of the Lord scripture study#Warnings in the Doctrine and Covenants

0 notes

Text

Ordo Salutis - The Order of Salvation

The phrase, “ordo salutis” is a Latin scholastic term that designates, “the order of salvation,” as it appears in Scripture. This is the theological doctrine dealing with the logical sequencing of the covenant planning and application of benefits in the redemptive work of God, through Jesus Christ, by the power of the holy Spirit….

Read more

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sunday Afternoon Session

Conducting: Henry B. Eyring

For All the Saints

Elder Dale G. Renlund

King Tutankhamun and the finding of Tuts tomb

He is our mark – if we imagine there is something beyond what He offers, we deny all His blessings

Focus on Him intentionally

Baptismal water doesn’t wash away sins. That is why we have the opportunity to repent.

Approach the sacrament the same way a new convert approaches baptism – with a contrite heart and spirit

With the temple close it can be easy to let little things get in the way of attending – do not take the temple for granted. When we do we look beyond the mark

Do not praise exotic sources for being enlightened – sometimes that is not the case

Remember and always focus on Jesus Christ. He is our Savior and Redeemer, the Mark towards whom we should look, and our Greatest Treasure

Elder John C Pingree Jr. 70

What is our understanding of truth in today’s world?

What is truth and why is it important?

Where do we find truth?

When we find truth how do we share it?

1 God is THE source of eternal truth.

2 The Holy Ghost testifies of all truth.

3 Prophets receive truth from God, and share that truth with us

4 We all play a crucial role in this process. God expects us to seek, receive and act on truth

Our ability to receive and understand truth is dependent on our relationship with God

Is the concept taught consistently in the scriptures and by living prophets?

Is it confirmed by the Holy Ghost?

Doctrine = eternal truths such as God is our eternal Father, Christ’s atonement etc

Unchangeable

Policy =application of doctrine based on current circumstances

Subject to change

Teach truth in a way that invites the converting power of the Holy Ghost

Truth should be conveyed with Christlike love – love without truth is hollow and lacks the promise of growth

Tell Me the Stories of Jesus

Elder Valeri V Cordon, 70

Help children establish a gospel culture

Righteous Intentional Parenting

1 Teach Freely

Liberally, generously, and without restraint

Spend meaningful time with them, use church resources (church moveis, come follow me)

2 Model Discipleship

By example keep the sabbath day holy, keep temple covenants.

3 Invite to Act

To seek individual revelation, work for and nurture their own testimony

We are God’s agents for our children. Create an environment where they can feel His love and guidance.

Accidental conversion is not a principle of the gospel of Jesus Christ

God will do everything He can without violating your agency.

As a parent you should do the same

Elder J. Kimo Esplin, 70

Hawaii and the battle of Okinawa

Baptisms for the dead, and temple work. People being taught in the spirit world.

Temple blessings can heal so much.

The Saviors work is to bind people together

Rejoice the Lord is King

Elder Garrit W. Gong Q of 12

Morse code locket “I I you”

Multilingual “I” “I” (Chinese ai) “You” = I love you

Languages of Gospel love

Warmth and Reverence

Service and Sacrifice

Covenant and Belonging

Daily sacrifices matter

Remember to speak with warmth and reverence about the Lord’s work

Sometimes things can affect our ability to serve, but hopefully never our desire

You need to feel the Lord’s love for those you serve – and for you when you serve.

When we serve in the gospel together, we find fewer faults and greater peace

Remember to minister with your hearts

Sociality and service often go together

The more we serve the better we can understand the nature of Christ.

Elder Christophe G. Giraud-Carrier 70

1 Samuel 16:7

God looks on the heart

We are His children, all of us without exception.

How sad is it that we honor labels more than we honor each other?

The gospel of Jesus Christ is the mediator

Discrimination is not ok

How we treat each other really matters.

I’ll Walk with You children’s song

Like Christ love others because it is the right thing to do.

Consider the Lillies

President Russell M. Nelson

What is the secret to living so long?

No what have I learned in almost a century if living

Heavenly Fathers plan for us is fabulous

This plan takes the mystery out of what comes next

What we do in this life matters

Savior’s atonement makes the plan possible

Adopt the practice of Thinking Celestial tm

Being spiritually minding

Mortality is a masterclass in learning what is of greatest eternal importance

Begin with the end in mind – carefully consider where each of your decisions will put you in the next life

Where will each decision place you? You get to choose

Take the long view – the eternal view

Put Jesus Christ first

Your obsession becomes your god – you look to it rather than to Him for solace

Struggling with addiction? Seek professional and spiritual help

Be chaste to attain celestial glory

Seek guidance from trusted voices

There are lots of things we can do to build faith

Temples!

Savai’i, Samoa

Cancún, Mexico

Piura, Peru

Huancayo, Peru

Viña del Mar, Chile

Goiãnia, Brazil

João Pessoa, Brazil

Calabar, Nigeria

Cape Coast, Ghana

Luanda, Angola

Mbuji-Mayi, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Laoag, Philippines

Osaka, Japan

Colorado Springs, Colorado

Tulsa, Oklahoma

Roanoke, Virginia

Kahului, Hawaii

Fairbanks, Alaska

Vancouver, Washington

Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia

Fun fact: he has announced 153 temples since becoming prophet

Teach me to Walk in the Light

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

why toyguru's an idiot pt. 1

and i mean, any lawyers feel free to weigh in on this, 'twas the work of an afternoon and a few spats in YouTube comment sections. transposing it here from a he-man forum bc i wanted to break shit down in an easier-to-digest format. there'll be a few supplementary arguments addressed in a later post, i'm just getting all my ducks in a row for efficiency's sake first. backstory to the situation (through me) is here and you can read ethan's post here. yes i capitalize Fair Use all the time, i mostly managed to type like a normal person but i'm never gonna be 100% Normal okay

Glossary

Copyright Infringement: "As a general matter, copyright infringement occurs when a copyrighted work is reproduced, distributed, performed, publicly displayed, or made into a derivative work without the permission of the copyright owner." - copyright.gov

Defamation: Any communication to a third party which may injure someone's reputation. There are certain exceptions which are protected—'mere vulgar abuse', for example, so insults are still A-okay. Typically, a defamation suit must prove that actual injury was done to the plaintiff, e.g. losing sales, somebody egged your house, that kind of thing, but defamation per se ('in itself') waives that for certain kinds of statements. Such as accusing someone of a crime, say, blackmail or harassment. Truth is an absolute defense for defamation: If you can prove it's true, it's not defamation, even if it injures that person's reputation.

Libel: If the defamation is published/written down, it's libel. This includes publishing things on the internet.

Bad Faith: While Good Faith is well-defined in law (the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealings, which governs all contract law), there's no consensus on Bad Faith. It's generally understood to mean ill will, dishonesty, deception—especially in order to gain an advantage. A good example is "surface bargaining" in organized labor, where one party goes through the motions of negotiation but has no intention of compromise.

Fair Use: The doctrine of Fair Use is an exception to standard copyright law, which provides for the use of copyrighted material under certain circumstances. Typically, it's what you cite when you've been brought to court for copyright infringement if you admit to the infringement (an affirmative defense), basically saying "Yes, okay, I did it, BUT here's why I think it doesn't matter." Officially it's no longer an affirmative defense, since (when correctly applied) Fair Use isn't copyright infringement, but—well. Its application is subjective.

Which brings us out of the glossary and into the meat of the matter.

Did Scott commit copyright infringement or was it fair use?

First, let's establish that yes, Ethan owns the copyright to his photos. In the US, copyright of photographs is granted from the moment of fixation. One may choose to register their photos with the Copyright Office, but it is not required unless they intend to bring alleged copyright infringement to court. There is a bulk rate that comes out to about 7¢ a photo, but it's a long and tedious process which is genuinely unnecessary without prospective court proceedings. Should Ethan and/or other artists whose work Scott has appropriated choose to pursue legal action, it's the method I'd recommend for registration with the Copyright Office, but again, not necessary.

Now then. Ethan's photographs (and indeed, the photographs of many other artists) were undeniably reproduced, publicly displayed, and made into a derivative work without the permission of the copyright holder. So, if it wasn't Fair Use, Scott (to use the legal jargon) super duper infringed that shit.

Let's take a look at Fair Use!

Title 17 of the United States Code (hereafter 17 U.S.C.) outlines copyright law in the US. Scott's 'representation' mentioned "the Copyright Act" because (well, I assume because) the Copyright Act of 1976, specifically, was the codification of Fair Use. We're concerned with section (§) 107:

Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include— (1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work. The fact that a work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors.

So, point by point—actually before we get to the determination factors, let's take a look at Scott's counterclaims (Ignoring the parts asserting that Ethan doesn't own his own photos, because nuh-uh):

"[...] this video is 100% Educational in nature and is eligible to use still images of consumer products as examples in a documentary as fair use."

Alright, first, a documentary is just a (typically) nonfictional film/movie composed of interviews, on-site footage, and reenactments. It's not someone talking over a slideshow. Even if Scott's work were a documentary, documentaries are not automatically protected by Fair Use. Just because there are pragmatic connotations of documentaries being educational, that doesn't change their semantic definition. Do you remember at the beginning of the pandemic when everyone was really into Tiger King? And then it turned out they lied and fabricated a bunch of stuff? Tiger King is a documentary.

Second. Please note that by calling it "a still image of a consumer product", in addition to dismissing Ethan's copyright a little more obliquely than usual, Scott is still materially wrong about his own rights as a (supposed) videographer. A still image of a consumer product is not, in itself, fair game. I can't just yammer on about, like, my politics or something and have a bunch of Mickey Mouse figurine pictures in the background, Disney would eat me alive. To claim Fair Use, the images must be utilized in one of the manners described by the doctrine. It's not that complicated! It's one paragraph!

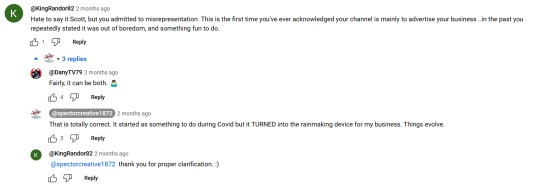

Third, and most significantly: Scott is here claiming that his videos are "100% Educational". So why's all his stuff monetized? Why did he tell Ethan he uses these videos to "feed his family"? Let's segue briefly into 17 U.S.C. § 107(1), which considers if the usage is commercial, or for nonprofit educational purposes. Nonprofit. Perhaps I'm biased, having only ever worked for nonprofits (and my college's gym, which I don't think counts despite never actually turning a profit), but to me nonprofit means any profits made will be invested back into the organization. Spector Creative, LLC is not a nonprofit. Scott Neitlich, the individual, is profiting from these videos. And while he could claim the proceeds were going into future video production, he'd need to demonstrate that through an audit—and like, we've all seen his videos lately. If the proceeds went anywhere, they could go to a camera. Or perhaps, a photography setup so he could take his own 'still images of consumer products'. He simply wouldn't be able to demonstrate that his expenses were business ones.

Un-segue. Counterclaim narrative 2:

"images are used under fair use doctrine. [...] I depend on this channel as my sole source of clients and am actively losing business due to his unjust and constant harassment."

You can't "use something under" the Fair Use doctrine, you're permitted to do something because of it. This is pedantic of me but whatever, I think we can intuit from all this that I'm a pedantic little freak in general. Anyway. He says he 'depends' on this channel, which he formerly implied contained only educational videos, and it's costing him 'business', which further undercuts his claims that his usage of Ethan's work is educational, and, as his "representation" has now said, that his channel is 'designed to educate, inform, and engage [his] audience on topics that are of significant educational value'. A channel cannot be a source of profit (and by Scott's own account, the SOLE source for referral of clients to generate further profit) and a nonprofit educational venture simultaneously. Actually, let me show you something he said in one of those YouTube comment sections rq, because he is A Fucking Idiot:

So more succinctly, it started out as being for fun (not even for education? I guess education can be pretty fun) before "evolving" into a mechanism for profit. This is also how I learned 'rainmaker' is a business colloquialism and not exclusively a reference to the conmen who would go around during droughts, but that's neither here nor there. Scott's representation also stated (in the same message):

"The images used are instrumental in illustrating these subjects more effectively and are used in a transformative manner that does not infringe upon or substitute the market for the original works."

I definitely prefer dealing with his representation's language, I must say. A coherent argument, if still flimsy, poorly researched, and somewhat disingenuous, is way more fun to disprove. Let's turn our attention back to those factors for consideration, specifically 17 U.S.C. § 107(1) and (2):

(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

Okay, so: We've established that Scott's work is of a commercial nature. Its educational value is dubious, though I suppose that's subjective (frankly all I've learned from him is that Mattel didn't own the copyright to the name Double Trouble when they made her in MOTUC, and I suppose obliquely that he's really fucking bad at picking names), but its use of Ethan's photos is far from 'instrumental'. Scott's use of vaguely-associated images has little to nothing to do with the actual words coming out of his mouth. How many times recently has he used screenshots of dictionary entries? Rather, the images (at least, Ethan's images) are serving their original purpose, showcasing the figures in question (heh) in an artistic composition and expression. Further, the videos I know to have been claimed are absolutely not transformative of the images themselves. I'm going to get technical for a second but bear with me—

Ringgold v. Black Entertainment Television, Inc., 126 F.3d 70 (2d Cir. 1997) found that the inclusion of a poster in the background of a TV shot which held the camera's focus was enough to determine infringement, as the accused had not obtained license from the copyright holder or her agent (the museum that sold the poster which reproduced her work). Because the poster was a deliberate set dressing to establish the location of the shot, and thus being used in its original capacity (as decorative artwork), it was not transformative enough to warrant Fair Use.

The Supreme Court actually addressed what qualifies something as transformative very recently, in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 143 S. Ct. 1258 (May 18, 2023), which I recommend reading at least the Wikipedia page for if you want a crash course in where we're at like, as a society regarding transformative use—but I digress. If an Andy Warhol print isn't transformative enough to find non-infringement in a commercial work, surely Scott's unaltered reproduction of copyrighted images isn't either.

Onto 17 U.S.C. § 107(3)

the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole;

This one is where I take a more subjective approach. The substantiality of the copyrighted work is often referred to as its "heart"; does the infringement take that which makes the copyrighted work unique or valuable? Los Angeles News Service v. KCAL-TV Channel 9, 108 F.3d 1119 (9th Cir. 1997) is the best example I could find offhand to demonstrate this, and frankly I think the court's finding is relevant, so I'm just going to post an excerpt of the Copyright Office's Index:

"The court found that while defendant’s use of the tape was arguably in the public interest because it was footage of a newsworthy event, the use was still commercial because defendant was in the business of gathering and selling news and competed with other stations for advertising dollars. Additionally, the court found that defendant’s airing of the footage with a voiceover failed to add anything new or transformative, and that although only thirty seconds of a four-minute video were used, it was still the “heart” of the work. Finally, the court found that defendant’s use of the footage could also potentially have a negative impact on plaintiff’s primary market, especially in light of defendant’s initial request to license the work."

So I bring it up because, to me—consumer of reviews—a good picture is a huge draw. It affects my decision to consume a review, because if I see a high quality photo, I know that the reviewer is invested in the process, and therefore more likely to have opinions I'll value. Also, pretty picture yay! Therefore a strong argument could be made that Ethan's photographs constitute the "heart" of his work, even though he also provides review and commentary on the figures. And as the court found above, a voiceover was not new or transformative enough to negate its commercial purpose, despite its purported Fair Use exemption of news reporting, because the competition between news stations for ad revenue provided a financial incentive for the appropriation of copyrighted works. Much like Scott's (monetized) channel is in competition with others, and is representative of his company and its interests, which is an entity in competition with other consultants and consulting firms. Like he didn't name it 'Toyguru', he named it Spector Creative. It's a company channel.

But I think the single most important argument against Fair Use is 17 U.S.C. § 107(4):

the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

I haven't had the chance to hammer this one into people as much as I'd like to. Weirdly, it never comes up—it seems like Scott's defenders haven't even read 17 U.S.C. § 107, isn't that crazy? Isn't that wild? My time's been better served shooting down the arguments they do make. But these infringements annihilate the potential market.

Before Scott and Ethan ever spoke, Scott perpetuated the devaluation of Ethan's product, both indirectly by encouraging the uncredited use of artists' work, and directly by, you know, stealing his art. If Ethan were to market himself as a toy photographer, there would be a significantly smaller clientele, because people will think they can just use and profit off of any old picture from Google Images if they can excuse it as "fair use". More egregiously—and this part makes me feel insane— how, in god's name, is anybody supposed to find Ethan to commission him for photographs if Scott erases his watermark like half the time.

All of the images I've identified from Scott's videos have been because I know how to identify uncited images, and track sources, not because he is promoting their work. I think the only artist I've ever seen him credit is Axel, and that's because it made him seem important and cool and legitimate. Regular people are not going to track down the pictures from a slideshow! If I handed my sister one of Ethan's photos and told her 'find the source for this image', she would stare at me blankly and google 'toy picture'. She might remember that watermarks exist for a reason with some prompting. Failing to mention where you got a picture from in like, a personal blog post, that's inconvenient (and potentially a dick move) but not the end of the world. Not only failing to credit the artists whose work you're using in a commercial context, but removing watermarks, failing to transform or iterate on the work at all? That's copyright infringement. Indisputably.

Ethan is fortunate enough to have a job outside his work, but if he didn't? If he decided to explore the potential market? He'd have to make his own advertisements, while Scott's company reaped in the profits for Ethan's labor and materials by using his art in their thumbnails without so much as a mention (well, a mention that wasn't accusing Ethan of a federal crime).

It comes down to Scott no longer producing video content, just audio over slideshows of content he didn't make or even ask permission to use. I won't suggest every creator take video of themselves, bc for a number of reasons I think that'd suck pretty bad, but he could have taken his own photos (presuming he owns the toys he's discussing), or used his LEGOsona, maybe even done some low-effort stop motion with that cutesy little set he built for it. But at the end of the day it was just too much work compared to grabbing other people's pics off the internet. And his behavior towards Ethan has been reprehensible since day one—lying, moving goal posts, libeling him, now trying to intimidate him with an implied lawyer. Guess what! That weighs against Fair Use, too!

Here's a fun little checklist that's sort of equivalent to a pro/con list for determining Fair Use, just a real basic sniff test. Take a look and see how things shake out for Scott.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books of the Bible

Here is a detailed list of the 66 books of the Bible, divided by the Old and New Testaments, along with their divisions and categories:

**Old Testament:**

**Pentateuch (5 books):**

1. Genesis

2. Exodus

3. Leviticus

4. Numbers

5. Deuteronomy

**Historical Books (12 books):**

6. Joshua

7. Judges

8. Ruth

9. 1 Samuel

10. 2 Samuel

11. 1 Kings

12. 2 Kings

13. 1 Chronicles

14. 2 Chronicles

15. Ezra

16. Nehemiah

17. Esther

**Poetry/Wisdom Books (5 books):**

18. Job

19. Psalms

20. Proverbs

21. Ecclesiastes

22. Song of Solomon

**Major Prophets (5 books):**

23. Isaiah

24. Jeremiah

25. Lamentations

26. Ezekiel

27. Daniel

**Minor Prophets (12 books):**

28. Hosea

29. Joel

30. Amos

31. Obadiah

32. Jonah

33. Micah

34. Nahum

35. Habakkuk

36. Zephaniah

37. Haggai

38. Zechariah

39. Malachi

**New Testament:**

**Gospels (4 books):**

40. Matthew

41. Mark

42. Luke

43. John

**History (1 book):**

44. Acts

**Pauline Epistles (13 books):**

45. Romans

46. 1 Corinthians

47. 2 Corinthians

48. Galatians

49. Ephesians

50. Philippians

51. Colossians

52. 1 Thessalonians

53. 2 Thessalonians

54. 1 Timothy

55. 2 Timothy

56. Titus

57. Philemon

**General Epistles (8 books):**

58. Hebrews

59. James

60. 1 Peter

61. 2 Peter

62. 1 John

63. 2 John

64. 3 John

65. Jude

**Apocalyptic (1 book):**

66. Revelation

This list represents the traditional order and grouping of the books of the Bible in most Christian denominations.

These are the 66 books that make up the Bible.

Title: The Significance of Each Book of the Bible

Introduction:

The Bible is a collection of 66 books that together form the inspired Word of God. Each book has its own unique message, themes, and significance that contribute to the overall story of God's redemption and love for humanity. Let's explore the importance of each book of the Bible.

Lesson Points:

1. The Old Testament:

- Genesis: The book of beginnings, detailing creation, the fall, and the establishment of God's covenant with His people.

- Exodus: The story of the Israelites' liberation from Egypt and the giving of the Law at Mount Sinai.

- Psalms: A collection of songs and prayers that express a range of human emotions and provide a guide for worship.

- Proverbs: Wisdom literature that offers practical advice for living a righteous and wise life.

- Isaiah: Prophecies about the coming Messiah and God's plan of salvation.

2. The New Testament:

- Matthew: Emphasizes Jesus as the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecies and the establishment of the kingdom of God.

- Acts: Chronicles the early spread of the Gospel and the growth of the early church.

- Romans: Explains the doctrine of justification by faith and the implications of salvation through Christ.

- Corinthians: Addresses issues within the church and provides practical guidance for Christian living.

- Revelation: Offers apocalyptic visions of the end times, the victory of Christ, and the establishment of the new heaven and earth.

3. Themes and Messages:

- Each book of the Bible contributes to the overarching themes of God's love, redemption, forgiveness, and salvation for all humanity.

- Together, these books provide a complete narrative of God's work in the world and His plan for His people.

Application:

- Take time to explore and study each book of the Bible, seeking to understand its unique message and significance.

- Reflect on how the themes and stories in the Bible can impact your own life and faith journey.

- Consider how the teachings and examples in the Bible can shape your beliefs and actions as a follower of Christ.

Conclusion:

The books of the Bible are not just separate entities but are interconnected parts of the larger story of God's redemption and love for humanity. Each book has its own importance and contributes to the overall message of God's plan for salvation. May we approach the study of the Bible with reverence and openness to the wisdom and guidance it offers for our lives.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Implied Covenant of Good Faith: The Silent Term in Every Contract

I. Introduction: The Unspoken Promise in Contractual Relationships II. Historical Origins: Kirke La Shelle v. Armstrong and the Formal Recognition of Good Faith III. Conceptual Foundations: Good Faith as a Tool of Justice and EfficiencyA. Ethical Imperative: Pacta Sunt Servanda and the Moral Dimension of Contracts B. Functional Utility: Reducing Transaction Costs and Ensuring Cooperative Performance C. Codification and Acceptance: From Common Law to UCC and the Restatement IV. Application in Commercial Contexts: From License Agreements to Supply Chains V. The Implied Covenant in Employment: From At-Will Doctrine to Fair Dealing VI. Limits and Controversies: Judicial Balancing and the Risk of Overreach VII. Conclusion: The Enduring Relevance of a Silent Covenant Implied Covenant of Good Faith: The Silent Term in Every Contract From Kirke La Shelle v. Armstrong to Employment Terminations

I. Introduction: The Unspoken Promise in Contractual Relationships

In the architecture of contract law, much attention is devoted to express terms—those commitments clearly articulated and mutually assented to by the parties. Yet, nestled silently within nearly every contract is an unexpressed but potent obligation: the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing. This principle ensures that neither party will do anything to destroy or injure the other’s right to receive the benefits of the agreement. Though invisible in wording, this covenant exerts formidable influence, restraining opportunistic behavior and imbuing contractual interpretation with a sense of justice.

From its judicial formulation in early 20th-century cases such as Kirke La Shelle v. Armstrong, the implied covenant has evolved to become a vital component of American contract law. Its reach extends across diverse contexts, including the often-contentious domain of employment terminations. This essay explores the origins, doctrinal development, and modern applications of this silent term, illuminating its indispensable function in upholding the ethical infrastructure of private agreements.

II. Historical Origins: Kirke La Shelle v. Armstrong and the Formal Recognition of Good Faith

The modern doctrine of the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing gained early prominence in the New York Court of Appeals case Kirke La Shelle Co. v. Armstrong, 263 N.Y. 79 (1933). There, the plaintiff held the exclusive right to produce a dramatic play. The defendant, by intentionally rendering the contract worthless through a separately orchestrated deal, effectively deprived the plaintiff of the benefit of its bargain. While no express term was violated, the court held that such conduct breached the implied covenant of good faith. Judge Pound, writing for the court, famously declared that “n every contract there is an implied covenant that neither party shall do anything which will have the effect of destroying or injuring the right of the other party to receive the fruits of the contract.” This statement crystallized the doctrine’s rationale: contracts are not merely bundles of explicit promises; they are also relational understandings that must be preserved from manipulation or subversion.

III. Conceptual Foundations: Good Faith as a Tool of Justice and Efficiency

The implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing operates at the intersection of moral integrity and legal pragmatism. Though often treated as a doctrinal mechanism for redressing contract breaches, it is more properly understood as an enduring normative standard—an ethical compass embedded in the jurisprudence of private obligation. Its theoretical underpinnings lie not only in the formal requirements of contract law, but in deeper philosophical commitments to justice, reciprocity, and trust as necessary conditions for human cooperation. A. Ethical Imperative: Pacta Sunt Servanda and the Moral Dimension of Contracts At its ethical core, the implied covenant of good faith revives and reinterprets the ancient legal maxim pacta sunt servanda—“agreements must be kept.” But unlike a rigid, formalist reading that emphasizes strict performance of express terms, the covenant insists on a richer, more holistic fidelity to the substance of the agreement. The obligation it imposes is not merely to avoid technical breach, but to refrain from actions that sabotage the mutual expectations upon which the contract was founded. This distinction becomes crucial in contexts where one party technically complies with the contract’s wording while rendering the other party’s benefits illusory or inaccessible. Such “bad faith opportunism” might manifest in withholding necessary cooperation, exploiting ambiguities for unilateral advantage, or engaging in strategic delay to frustrate performance. While these tactics may not violate any explicit term, they are antithetical to the relational foundation of contract law—a foundation predicated on trust, reciprocity, and the moral duty not to act deceptively or destructively toward one’s counterparty. Moreover, the covenant reflects an ethical ideal of fairness in exchange. It reminds contracting parties—and courts—that contracts are not mere tools for maximizing self-interest, but instruments for cooperative problem-solving, often between parties of unequal bargaining power. The implied covenant thus tempers the individualistic ethos of classical contract theory with the communitarian insight that obligations must be fulfilled not only formally, but honorably. B. Functional Utility: Reducing Transaction Costs and Ensuring Cooperative Performance Beyond its moral significance, the implied covenant also plays a vital functional role in making contract law workable and efficient. In an idealized world, parties could foresee every contingency and specify in minute detail how each should be handled. In reality, contracts are necessarily incomplete. The world is too complex, human relationships too fluid, and language too imprecise to anticipate and articulate every possible form of behavior that might threaten the contract’s aims. Absent the implied covenant, parties would be forced to draft exhaustively, enumerating prohibitions against every imaginable form of exploitation. This would raise transaction costs to an unsustainable level and deter productive agreements. The covenant, by contrast, operates as a “default term” supplied by law—an interpretive backstop that fills gaps, constrains discretion, and ensures that both parties act in ways consistent with the contract’s reasonable expectations. In economic terms, the covenant helps prevent opportunism—behavior that extracts private gains at the expense of collective surplus. Oliver Williamson, the Nobel Prize-winning economist, emphasized the importance of such legal constraints in preserving the integrity of long-term cooperative arrangements. The implied covenant promotes relational stability by signaling that the legal system will not reward strategic bad faith or manipulation of formal loopholes. This function is especially salient in contracts involving discretion, dependency, or long-term performance—such as franchise agreements, joint ventures, employment contracts, and licensing arrangements. In these cases, the parties rely not merely on written terms but on ongoing cooperation and mutual trust. The implied covenant safeguards this trust by ensuring that the exercise of discretion—whether in terminating, modifying, or enforcing the contract—is not arbitrary, retaliatory, or self-serving to the point of destruction. C. Codification and Acceptance: From Common Law to UCC and the Restatement The normative and practical force of the implied covenant is reflected in its codification and wide acceptance. Section 1-304 of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) declares: “Every contract or duty within this Act imposes an obligation of good faith in its performance and enforcement.” Though modest in appearance, this provision has profound consequences: it institutionalizes the principle that good faith is not optional but inherent in all commercial dealings covered by the UCC. Similarly, Section 205 of the Restatement (Second) of Contracts provides: “Every contract imposes upon each party a duty of good faith and fair dealing in its performance and enforcement.” The commentary to this section further clarifies that good faith excludes a variety of disloyal acts—such as evasion, subterfuge, and abuse of power—that undermine the agreed-upon structure of cooperation. Notably, these codifications do not treat the covenant as an ornamental principle or vague aspiration. Rather, they integrate it into the core of modern contract theory, treating it as an essential condition for market function and judicial fairness. Courts across jurisdictions have cited these provisions in interpreting ambiguous terms, policing abuses of discretion, and remedying concealed sabotage. In sum, the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing is both a moral commitment to cooperative honesty and a functional tool that preserves the efficiency and viability of contractual relations. By ensuring that the letter of the contract does not become a weapon against its spirit, the covenant sustains a legal order in which promises are not just formal obligations but expressions of mutual reliance, trust, and justice.

IV. Application in Commercial Contexts: From License Agreements to Supply Chains

In the world of commercial contracts, where transactions often involve high stakes, ongoing relationships, and significant asymmetries of power, the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing emerges not only as a legal doctrine but as a stabilizing force. It acts as a restraint on opportunism, especially where one party enjoys discretion—explicit or implicit—over key aspects of performance, enforcement, or termination. Courts have repeatedly invoked this covenant to prevent abuses of such discretion, thereby protecting the integrity of commercial arrangements from being hollowed out by self-interested exploitation. A. Discretion as a Point of Vulnerability The touchstone for many good faith disputes is discretionary power. When one party to a contract is granted unilateral discretion—whether to terminate, modify, approve, allocate resources, or perform obligations—the opportunity for opportunism inevitably arises. The implied covenant functions to cabin that discretion within the bounds of fairness and reasonableness. The underlying logic is that discretion must be exercised in a manner that does not deprive the other party of the expected benefits of the agreement. In Fortune v. National Cash Register Co., 373 Mass. 96 (1977), the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court confronted this exact problem. The plaintiff, a long-serving salesman, had secured a significant deal that would have entitled him to a substantial commission. Before the commission was paid, the employer terminated his contract under its at-will clause. Although technically permissible under the letter of the agreement, the court concluded that the termination, motivated by a desire to avoid compensating the employee, violated the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing. The decision reinforced the idea that discretion—especially when used to evade payment or subvert reliance interests—must be exercised in good faith. This principle has rippled through employment, agency, and sales agreements, discouraging the use of termination or other discretionary clauses as tools of unjust enrichment or avoidance of accrued obligations. Courts have not prohibited employers or principals from exercising discretion, but they have required that such exercises be anchored in legitimate business purposes rather than in malice, retaliation, or economic predation. B. Franchise and Licensing Agreements: The Struggle Against Cannibalization The implied covenant finds particularly fertile ground in franchise and licensing relationships, which are typically characterized by long-term collaboration, ongoing performance, and unequal bargaining power. These contracts often give the franchisor or licensor broad control over pricing, geographic expansion, marketing, and product development. When this discretion is exercised in ways that harm the franchisee or licensee, courts increasingly look to the implied covenant as a judicial compass. One common form of bad faith is territorial cannibalization, where a franchisor opens a competing, company-owned store near an existing franchise, thereby drawing away customers and diluting the franchisee’s investment. Even where the contract permits such openings, courts have sometimes found violations of good faith when the franchisor's actions are so economically destructive as to eviscerate the franchisee’s reasonable expectations under the agreement. In Burger King Corp. v. Weaver, 169 F.3d 1310 (11th Cir. 1999), the court held that the franchisor did not breach the implied covenant by opening a new location, but it acknowledged that such conduct could raise concerns if done arbitrarily or with clear intent to damage an existing franchisee. By contrast, in Atlantic City Coin & Slot Serv. Co. v. IGT, 14 F. Supp. 2d 644 (D.N.J. 1998), the court found that the licensor had breached the covenant by refusing to supply necessary parts and support to a licensee, thus rendering the licensee’s business operations unviable. These cases reflect a growing judicial awareness that contract law must accommodate relational dependencies in complex commercial environments. The implied covenant thus functions as a kind of “relational justice clause,” demanding that dominant parties exercise power in a way that sustains, rather than undermines, the mutual benefit at the heart of the agreement. C. Supply Chains and Procurement: Faith in the Flow of Commerce The globalized supply chain offers another realm where good faith plays a critical—if often underappreciated—role. Manufacturers, distributors, and retailers often operate through multi-tiered contracts in which the timing, quality, and volume of deliveries are left to one party’s discretion. For instance, a buyer may reserve the right to reject goods for nonconformity, or to demand “just-in-time” delivery based on shifting needs. When this discretion is exercised abusively—such as through excessive delay, arbitrary rejection, or manufactured “nonconformance” to escape obligations—courts have occasionally stepped in to enforce the implied covenant. In Net2Globe International, Inc. v. Time Warner Telecom of New York, 273 F. Supp. 2d 436 (S.D.N.Y. 2003), the court found that the defendant’s unreasonable delay in provisioning a telecommunications service, though not a literal breach of a deadline, constituted a breach of the covenant due to the deliberate frustration of the contract’s core purpose. These rulings reinforce that in the delicate and interdependent world of modern commerce, trust in the fair execution of contracts is indispensable. The implied covenant ensures that commercial players do not engage in post-contractual behavior designed to extract surplus or shift risk unfairly, particularly where one party’s discretion governs vital logistical or economic functions. D. Financial Instruments and Commercial Leases: Duty Within Formality Even in highly formalized instruments such as commercial leases and financial agreements, where parties often attempt to contract around uncertainty through precision, the implied covenant retains force. Courts have used it to protect tenants from landlords who impose arbitrary obstacles to renewal or refuse to make reasonable accommodations, and to prevent lenders from calling in loans or triggering default clauses in a manner calculated to seize collateral or restructure relationships on more favorable terms. In Wilshire Westwood Associates v. Atlantic Richfield Co., 20 Cal. App. 4th 732 (1993), a California court ruled that a lessor’s refusal to approve a tenant’s proposed assignee—despite a contractual “reasonableness” standard—was a breach of good faith, as the denial was not based on legitimate business concerns but on speculative or pretextual grounds. Similarly, courts have reviewed decisions made under “sole discretion” clauses in financing contracts to ensure they are not exercised in a capricious or abusive manner. While absolute discretion clauses are often upheld, the implied covenant can still serve as a backstop against fraud, manipulation, and conduct that is plainly inconsistent with commercial norms. In conclusion, the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing serves as an essential check on discretionary power in commercial settings. It fortifies the cooperative premises of complex transactions, deters strategic manipulation, and reaffirms the moral foundation upon which commercial law is built. By restraining opportunism and encouraging consistency with the contract’s spirit, the covenant helps ensure that private law remains not only a mechanism of enforcement but also a vessel for fairness, trust, and shared enterprise.

V. The Implied Covenant in Employment: From At-Will Doctrine to Fair Dealing

Perhaps the most controversial and dynamic arena for the implied covenant is employment law. In the United States, the employment-at-will doctrine permits employers to terminate employees for any reason not specifically prohibited by law. Yet courts in some jurisdictions have softened this harsh rule by invoking the implied covenant of good faith. In Cleary v. American Airlines, 111 Cal. App. 3d 443 (1980), the court held that a long-time employee could not be dismissed in bad faith, particularly when the termination was motivated by retaliation or a desire to deprive him of earned benefits. The reasoning echoed that of Kirke La Shelle: a party should not evade contractual obligations through tactical terminations. Still, the application of the covenant in employment remains inconsistent across states. Some courts, such as in New York, continue to maintain a strict interpretation of at-will employment and reject good faith limitations unless explicitly contracted. Read the full article

0 notes

Text

UNDERSTANDING THE BIBLE 2

1 BRETHREN, MY HEART'S DESIRE AND PRAYER to GOD FOR ISRAEL IS THAT THEY MAY BE SAVED.

2 For I bear them witness that they have a zeal for God, but not according to knowledge.

3 FOR THEY BEING IGNORANT OF God’s RIGHTEOUSNESS, AND SEEKING TO ESTABLISH THEIR OWN RIGHTEOUSNESS, HAVE NOT SUBMITTED TO THE RIGHTEOUSNESS OF GOD.

4 FOR CHRIST IS THE END OF THE LAW FOR RIGHTEOUSNESS TO EVERYONE WHO BELIEVES."

Romans 10:1-4 (NKJV)

Any number of Christians who claim to be Jesus' disciples or followers but are adherent of old testament law are ignorantly rendering the sacrificial work of Christ Jesus on the cross useless, they are rubbishing the work of mankind's salvation obtained through Jesus' death and resurrection:

16 KNOWING THAT A MAN IS NOT JUSTIFIED BY THE WORKS OF THE LAW BUT BY FAITH IN JESUS CHRIST, EVEN WE HAVE BELIEVED IN CHRIST JESUS, THAT WE MIGHT BE JUSTIFIED BY FAITH IN CHRIST AND NOT BY THE WORKS OF THE LAW; FOR BY THE WORKS OF THE LAW NO FLESH SHALL BE JUSTIFIED: 17 "BUT IF, WHILE WE SEEK TO BE JUSTIFIED BY CHRIST, WE OURSELVES ALSO ARE FOUND SINNERS, is Christ therefore a minister of sin? CERTAINLY NOT! 18 FOR IF I BUILD AGAIN THOSE THINGS WHICH I DESTROYED, I MAKE MYSELF A TRANSGRESSOR. 21 I DO NOT SET ASIDE THE GRACE OF GOD; FOR IF RIGHTEOUSNESS COMES THROUGH THE LAW, THEN CHRIST DIED IN VAIN.” (Galatians 2:16-18,21 NKJV).

Whoever claims to be a believer or a disciple or a Christian who is living by the old testament principles has set aside the grace of God. Such is rendering the sacrificial work of Christ Jesus on the cross useless. And there is a grievous consequence for doing such a thing: "OF HOW MUCH WORSE PUNISHMENT, DO YOU SUPPOSE, WILL HE BE THOUGHT WORTHY WHO HAS TRAMPLED THE SON OF GOD UNDERFOOT, COUNTED THE BLOOD OF THE COVENANT BY WHICH HE WAS SANCTIFIED A COMMON THING, AND INSULTED THE SPIRIT OF GRACE?" (Hebrews 10:20 NKJV).

The so-called believers who are still practicing the old testament principles are insulting the spirit of Grace and rendering the sacrificial blood of Jesus Christ common.

There are some so-called spiritual churches which their prophets and prophetesses still tell them to go and bath in the rivers, pray with the lightning of candles, burning of incense, and killing of animals for sacrifices. They usually deceive or bamboozle their followers with the scriptures found in the old testament of the Bible. The fact that those things are kept in the old testament of the Bible that we are using does not mean that believers in Christ should observe or practice them. Things written in the old testament are for our learnings, admonitions, that we would not repeat the mistakes made by many of those who walked with God then (1 Corinthians 10:11).

Also, It is said: "ALL SCRIPTURE IS GIVEN BY INSPIRATION OF GOD, AND IS PROFITABLE FOR DOCTRINE, FOR REPROOF, FOR CORRECTION, FOR INSTRUCTION IN RIGHTEOUSNESS" (2 Timothy 3:16 NKJV).

The meaning and application:

a. Some parts of the Bible, Scripture, is profitable for doctrine, that is, profitable for teaching.

b. Some for reproof; that is, for rebuke, reprimand, scolding, or talking-to.

c. Some for correction; in other words, they are written or recorded in the Bible to correct the contemporary believers that such things should not be done as seen done by those in the old testament days (1 Corinthians 10:11).

There are things found in the Bible, though they are found there, they are actually not meant for practice; they are for corrections and admonitions or warnings. They are not at all meant to be done and repeated by the new testament believers.

d. Some for instructions in righteousness. In other words, some part of the Bible are written for instructions; that is, for admonishments or warnings. They are meant to give guidance and directions to the believers in Christ Jesus.

Therefore, If you are ignorantly practicing the old testament principles that are meant for corrections as the things to be practiced, you are abusing the Bible. To abuse means to misuse; the incorrect or improper use. It means you are desecrating and profaning the Bible.

If you are guilty of this, repent today.

Peace.

• You will not fail in Jesus' name.

Should there be any ailment in your body, receive your healing now in Jesus' mighty name.

Hold of sickness is completely broken and never to raised or built again in Jesus' name.

Peace.

STEPS TO SALVATION

• Take notice of this:

IF you are yet to take the step of salvation, that is, yet to be born-again, do it now, tomorrow might be too late (2 Corinthians 6:1,2; Hebrews 3:7,8,15).

a. Acknowledge that you are a sinner and confess your Sins (1 John 1:9); And ask Jesus Christ to come into your life (Revelation 3:20).

b. Confess that you believe in your heart that Jesus Christ is Lord, and that you confess it with your mouth, Thus, you accept Him As your Lord and Saviour (Romans 10:9,10).

c. As you took the steps A and B your name is written in the Book of Life (Philippians 4:3; Revelation 3:8).

- If you took the steps As highlighted above, congratulations, It means you are saved—born-again. Join a Word based 1 in your area and Town or city, and be part of whatever they are doing there. Peace!

Note:

a. I want you to follow us for more edifying content.

b. Endeavour to share this message. God bless you.

#christianity#christian living#gospel#christian blog#jesus#the bible#devotion#faith#my writing#prayer

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Reductive-Institutional Approach to Scripture

April 26, 2025

Vincent Cheung

The Redemptive-Historical Framework

The redemptive-historical approach interprets Scripture as the progressive revelation of God’s plan, culminating in the person and work of Jesus Christ. Rather than treating biblical texts as isolated moral teachings or abstract doctrines, it recognizes that every passage contributes to a unified, unfolding narrative of redemption. In theory, this method guards against atomizing Scripture into scattered life lessons or disconnected theological points. It invites the reader to trace the divine initiative throughout history, to understand the covenants, the types, the promises, and the fulfillments that center on Christ. When rightly employed, it draws attention not merely to events or principles, but to the character and activity of God revealed across time, enabling a more integrated and God-centered understanding of the Bible as a whole.

The Corruption of the Framework

Although the redemptive-historical approach claims to magnify Christ, in the hands of preachers and scholars it most often functions as a means to limit what people are permitted to believe about him. They routinely use it to suppress the full testimony of Scripture, filtering every passage through a narrow framework that permits only certain pre-approved attributes or actions of Christ. In practice, they never implement a redemptive-historical approach to Scripture, but a reductive-institutional approach that mutilates Christ. A text might clearly reveal him as a healer, a miracle worker, or a provider in response to faith, but these features are then reclassified as merely illustrative or symbolic, never meant to apply to the reader, never meant to describe what Christ does now. In this way, the method is used to amputate the very truths it claims to reveal.

This results in a Christ who is not defined by the totality of Scripture, but by the restrictions imposed by the interpreter. The method becomes a tool of theological reductionism. Whatever Christ says about himself in a given passage is often discarded in favor of a generic summary that aligns with a predetermined portrait. By insisting that the text is “only about Christ,” and then dictating what that must mean, the theologian nullifies the revelation of Christ already present in the passage. It is a sleight of hand disguised as reverence, replacing exegesis with evasion. This not only flattens Christology, but disables the reader from receiving what the text promises, commands, and reveals.

The effect is spiritual disfigurement. A method that should expand the believer’s vision of Christ ends up shrinking it. A method that should inspire faith ends up installing unbelief. It is now common for those who espouse this approach to brazenly dismiss healing, miracles, prophetic gifts, or answered prayer as applications of the text, even when the text itself speaks plainly about these things. The redemptive-historical approach, as commonly practiced, has become a sophisticated technique for denying the power of God while maintaining a veneer of scholarship and a superficial allegiance to Scripture.

The Rightful Use of the Framework

The redemptive-historical approach is valid in principle. Scripture truly does reveal Christ throughout its history, covenants, types, and promises. But a proper use of the approach must begin with submission to the text itself. It must allow the passage to reveal Christ on its own terms, rather than force the passage to conform to a predetermined image of Christ. The method becomes faithful only when it listens to the voice of God in each specific place, drawing out what he says about himself in that context, without preemptively discarding aspects that make the interpreter uncomfortable. The aim is not to reduce all passages to a single pre-decided theme, but to encounter the manifold wisdom of God in the diversity of revelation.

A faithful use of this approach will expand our knowledge and strengthen our faith. Instead of silencing texts that speak of healing, miracles, or spiritual power, it will recognize these as dimensions of Christ’s self-revelation. It will not discard the Christ who heals in answer to faith, or the Christ who commands nature, or the Christ who empowers his people by the Spirit. It will allow the text to teach us how Christ reveals himself, how he deals with people, and what he expects from those who believe in him. A redemptive-historical reading that does not lead to greater faith in Christ and greater expectation of his miraculous power has failed both as a method and as a theology. Its proper function is not to confine, but to unfold. It is not to guard against misapplication by denying application altogether, but to rightly instruct us in who Christ is and what he is doing now.

From Text to Christ: What We Are Meant to See

When the redemptive-historical approach is used rightly, it restores the authority of the text, the fullness of Christ, and the inheritance of the believer. Instead of silencing Scripture, it allows each passage to speak in its own voice, revealing dimensions of Christ that are too often ignored. We see not only the Christ who forgives sins, but the Christ who heals bodies, drives out demons, pours out abundance, and empowers his people to act in his name. The miracles of Jesus are not merely signs that he is the Messiah. They are revelations of what the Messiah is like, and what he continues to do for those who believe.

A proper reading of the Old and New Testaments will affirm not only salvation from sin, but also the outpouring of the Spirit, the authority of faith, the increase of supernatural abilities and ministries, and the evident intervention of God. It will teach that we walk in the legacy of Abraham, Moses, Elijah, and Paul, not just as students of history, but as inheritors of promise. The same Christ who acted in the past is active now, and the same power that parted the sea and raised the dead is available to those who believe. This is not sentimental reading or motivational abuse of the text. It is the natural result of letting the text speak plainly about Christ and taking him seriously.

A faithful redemptive-historical reading will not leave the believer with less. It will leave him with more: more vision, more confidence, more obedience, and more faith. It will not reduce the Christian life to waiting for heaven. It will compel him to take possession of what Christ has already given, and to press forward in faith. When Scripture is read as it was meant to be read, the church does not shrink back into theological minimalism. It rises to proclaim and demonstrate the full gospel of Jesus Christ: in word, in power, and in truth.

0 notes

Text

Good morning.

Our detour through John's Good News now at an end, today we return to Mark's account of Jesus's ministry. Hot on the heels of his miracle of the multiplication of the loaves – and, as John would have it, the controversy that arose afterward – Jesus finds himself pulled into a different sort of controversy about food.

This argument will prove to be so frustrating to Jesus that, after he says his say, he'll leave Jewish territory entirely, aiming to hide from the crowds in Syro-Phoenecian Tyre.

But, as we've recently seen from John, Jesus is no stranger to frustrating arguments, nor to being misunderstood. Why is this particular argument what finally breaks his patience?

Let's first talk about the specific rule that kicks off this controversy: washing your hands before meals. In our time, this is fairly normal, to avoid getting germs inside you. In Jesus's time… insisting on it was a Jewish peculiarity. It seems to have derived from the Mosaic rules for the Temple priests, slowly expanded upon by concentric doctrinal safety fences until they included everyone. There's some confusion as to the timeline, however; modern Jewish reckoning says that the universally applicable mandate to wash before meals was invented after the Second Temple's destruction in 70 AD, adapting a Temple-related commandment which was to be "permanent", "from generation to generation" to a world where there was no Temple at all. And yet somehow Mark – writing in 75 AD at the latest – seemed to think it was already a long-established tradition during Jesus's ministry.

So this seems like an innocuous rule for Jesus to get so hung up on when people ask him why his disciples don't always follow it. He could easily turn around to his disciples and say, "hey, the Rabbis are the religious authorities for now, so do what they say", like he later would in Matthew's account. Or else he could have, like the Apostles eventually did, argued that those followers of his were covered under Noachide rather than Mosaic law.

But Jesus chose, instead, to put up a fight about the doctrine itself, as a proxy battle about Rabbinical extrapolations of God's law in general. And the fight he puts up is strange. He doesn't challenge their reasoning, as other rabbis might. Rather, he goes straight to the results of the reasoning, giving – in the full version of the encounter – an example of how Talmudic precedents (which were, at the time, oral rather than written) create a "letter of the law" that can contradict the law's spirit.

This is, after all, the weakness of a covenant based on statutes and decrees. It becomes easy to focus on the rules themselves, rather than remaining concerned with understanding the underlying principles which gave rise to those rules. Combine with that a practice of interpreting and extrapolating on those rules as caselaw, and you can quickly find that these minor deviations have multiplied to leave you hopelessly lost.

So Jesus bypasses the legalistic arguments, the arguments based on interpretation, and skips straight to the results. That's his approach to doctrine generally: skip to the results and use that to assess whether the process was correct. "By their fruits you shall know them."

And from here he goes one step further, and argues – though quietly – that even parts of the Mosaic law have outlived their service to that principle, to the purpose of the law that Moses himself provides today (i.e. "that you may live, and may enter into the land which God is giving you"). And this is the part that frustrates him: nobody – not the scholars he was arguing with, not the crowds, not even his own inner circle, fresh from their miraculous tour of the region – seems ready to go that far. Even when Jesus gives a more explicit hint as what he's saying, the Apostles don't seem to get the gist; the meaning of his words are added only in a parenthetical by Mark, who was writing decades later, long after the letter from Jerusalem that loosened this law more explicitly.

If part of Jesus's role was to move us from a covenant of statues and decrees, to the covenant of "God's logic is written in our hearts", that failure to even consider that the law might not be absolute must have been an incredibly frustrating experience. No wonder he wanted to throw up his hands and leave for a faraway region where there'd be no-one to argue with.

But… this deadly tendency which Jesus criticizes today… it's a problem for us Christians as well. We may not have Talmudic case law, but we absolutely have our own ironclad, human-derived doctrines, and without even the Jewish escape hatch of pikuach nefesh, of "most of the Law is suspended when necessary to save a specific human life, because the purpose of the law is that we might live".

So we should not take Jesus's words today as any kind of mark of Christian superiority. Rather – as always, when Jesus criticizes the religious authorities of his time – we should imagine him talking about the authorities of our time, and apply his warnings to our own religious dogmas and practices.

What fruit do they bear? Are they doctrines of life, or death? Are they still relevant to what's really important, or have they gotten so tied up in metaphysical inside baseball that they've got nothing to do with the outside world anymore?

Because only when we get this right can we become the sort of people Moses imagines, who the world can look at and recognize that there's something greater than ourselves behind what we're doing. Only then can we "welcome the word that has been planted in us", as the correspondent James urges us today. Only then can we transcend a legalistic covenant of statutes and become God's own people, his law written in our hearts.

0 notes

Text

Unveiling Modern Theophany: Joseph Smith's First Vision and Ancient Biblical Encounters

The First Vision, by Del Parson Joseph Smith’s First Vision stands as a pivotal moment in the history of the Church, comparable to significant prophetic encounters found in ancient scriptures. How does this modern theophany deepen our understanding of personal revelation and divine communication? In this post, I’ll explore the layers of Joseph’s experience within the context of biblical events,…

#Bible verses about standing firm in your testimony#Enduring trials for spiritual growth#Faith-based scripture study guide#First Vision as a pattern for seeking God’s guidance#God answers prayers Bible verses#God the Father and Jesus Christ revelation#Gospel Restoration study guide#How Joseph Smith’s First Vision teaches us to seek wisdom#How to hear God’s voice in prayer#How to receive personal revelation#How to remain faithful during spiritual challenges#Inductive Bible study techniques#James 1:5 asking God for wisdom#Joseph Smith First Vision study guide#Joseph Smith—History 1:1–26 explained#Overcoming doubt and finding spiritual answers#Overcoming spiritual opposition#Pattern for personal revelation#Practical application of Joseph Smith’s testimony#Practical steps for personal revelation#Prayer and scripture study guide for personal revelation#Scripture references for personal revelation and faith#Seeking truth in a confusing world#Spiritual breakthroughs after trials#Strengthening your testimony through scripture#Study tips for Doctrine and Covenants#The role of scripture in personal growth and revelation#Thompson Chain Reference Bible study#Understanding God’s will through prayer#Understanding the First Vision in the Restoration of the gospel

0 notes

Text

The phrase, “ordo salutis” is a Latin scholastic term that designates, “the order of salvation,” as it appears in Scripture. This is the theological doctrine dealing with the logical sequencing of the covenant planning and application of benefits in the redemptive work of God, through Jesus Christ, by the power of the holy Spirit…

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Comprehensive Guide to the Transfer of Property Act

The Transfer of Property Act (TPA) holds a pivotal position in the realm of real estate transactions in India. It serves as the legal framework governing the transfer of property rights, ensuring transparency, legality, and fairness in dealings. In this blog post, we delve into the intricacies of the Transfer of Property Act, shedding light on its key provisions and their implications.

Understanding the Basics:

The Transfer of Property Act, enacted in 1882, aims to regulate the process of transferring property rights from one party to another. Whether it's buying, selling, or leasing immovable property, the TPA provides a structured legal foundation for these transactions. It is essential for property owners, buyers, and legal professionals to have a comprehensive understanding of this act to navigate the complexities of real estate dealings.\

Key Provisions of the Transfer of Property Act:

Definition of 'Property':

The TPA defines 'property' in a broad context, encompassing both movable and immovable assets. Understanding this definition is crucial to discern the scope of the act and its applicability to different types of assets.

Modes of Property Transfer:

The act outlines various modes of transferring property, including sale, mortgage, lease, and gift. Each mode comes with its own set of legal requirements and implications, making it imperative for parties involved to adhere to the prescribed procedures.

Conditions and Covenants:

The TPA specifies conditions and covenants that parties must adhere to during property transactions. These include the transferor's capacity to transfer, the transferee's capacity to acquire, and the legality of the purpose for which the property is transferred.

Doctrine of Lis Pendens:

This doctrine, as outlined in the TPA, highlights the importance of disclosing ongoing legal proceedings related to the property during its transfer. Failure to disclose such information can render the transaction voidable.

Rights and Liabilities of Parties:

The act delineates the rights and liabilities of both transferors and transferees. Understanding these rights is crucial for safeguarding interests and avoiding legal disputes.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the Transfer of Property Act serves as the cornerstone of real estate transactions in India. Whether you are a property owner, buyer, or legal professional, a profound understanding of its provisions is indispensable for navigating the intricate landscape of property transfers. Stay informed, adhere to legal procedures, and ensure a smooth and lawful transfer of property rights under the guidance of the Transfer of Property Act.

0 notes

Text

youtube

COMMENTARY:

Jesus is the euangelion. He is the Gospels. Without Jesus, the Gospel don't exist. The Gospel are the Body of the Christ, The literature is alive. It is not broken pottery, alone. It includes broken pottery, but before it is broken and how it became broken.

The Gospels begin with the 10th Legion that regulated the area of Galilee from Capernaum to the Mount of Olives. They were part of the fabric of Pax Romana of the economic ecology of the Mediterranean basin for a thousand years. Jesus, JOhn Mark and Josephus grew up around these soldiers like the German kids grew up with GIs in the fifties when I was there. Everybody in that region was living large.Because of the Romans. The horizontal structures of the Roman Republic as defined by the Italian Cohort that formed the founding unit of the Praetorian Guard that was the core of the administrative state of Rome. The 10th Legion kept track of local politics as a routine function of force security, They had an excellent network of spies within their Area of Operations, or AO as we called it in Vietnam.

When it comes to soldiering, it's SOS/DD and another day in Paradise.

You and Richard Carrier and the JEsus Seminar are in denial of this fact It's offensive to me, YOu offend the literature of the Bible by devolving it to the finite status of history. Literature is the infinite game. Linguistics is an inquiry into the magic of language. At what point does the oral tradition become literature? The Gospel of Mark was never oral history. It was distilled from the intelligence archives of the 10th Legion, IEvery phrase in the Gospels and Acts book marked with the Greek word translated as "immediately" and variations, designated by εὐθὺς , This is an apparatus of the genre of military intelligence reports and appreciations. Each εὐθὺς is a spy report that was logged in to the evidence locker of the 10 Legion. Before Jesus was arrested, except for Acts 10:16 and the three applications in John, one describing the splitting of Jesus as a part of the unilateral covenant cutting ceremony of the Cross that Talked that became the origin of Hebrews and the Apostles Creed. Hebrews is the Christian doctrine of the Christian centurions of the Italian Cohort, The scuttle butt of the Talking Cross went through the 2000 soldiers in the Praetorian during the Jewish holiday and crowd control like Legion went into the 2000 pigs of Mark 5.

Your entire premise of the lost meaning of the Gospels is pure fallacy, The issue for me is whether you realize your scholarship is based on fallacy as a deliberate method of inquiry or because, as a religious fraud, it makes a whole lot more money than even the MAGA Mega Pro-Life Calvinist Evangelicals of the Campus Crusade for Christ Total Depravity Gospel. The Total Depravity Gosple is the doctrine of Christian Nationalism and MAGA Mike Johnson the David Koresh of the House Freedom Caucus.

0 notes

Text

Help! I Don’t Enjoy Reading the Old Testament

New Post has been published on https://www.koasinag.com/help-i-dont-enjoy-reading-the-old-testament/

Help! I Don’t Enjoy Reading the Old Testament

Help! I Don’t Enjoy Reading the Old Testament

February 13, 2024

by:

Jason S. DeRouchie

This article is part of the Help! series.

Nuturing Delight

The Old Testament (OT) is big and can feel daunting, especially because it is filled with perspectives, powers, and practices that seem so removed from Christians today. While we know that the psalmist found in it a perfect law that revives the soul, right precepts that rejoice the heart, and true rules that are altogether righteous (Ps. 19:7–9), we can struggle to really see how spending time in the initial three-fourths of the Christian Scriptures is really “sweeter than honey and dripping of the honeycomb” (Ps. 19:10). How can we nurture delight in the OT?

1. Remember that the Old Testament is Christian Scripture.

What we call the OT was the only Scripture Jesus had, and the apostles stressed that the prophets wrote God’s word to instruct Christians. Paul says, for example, that God’s guidance of Israel through the wilderness was “written down for our instruction, on whom the end of the ages has come” (1 Cor. 10:11). Indeed, “whatever was written down in former days was written for our instruction, that through endurance and through the encouragement of the Scriptures we might have hope” (Rom. 15:4).

Peter emphasized that “it was revealed to them [i.e., the OT prophets] that they were serving not themselves but you”—the church (1 Peter 1:12). This means that Moses and the prophets recognized that they were writing for a future community that would be able to know, see, and hear in ways most of Israel could not (Deut. 29:4; Deut. 30:8; Isa. 29:18; Isa. 30:8; Jer. 30:1–2, 24; Jer. 31:33; Daniel 12:5–10). In short, the OT is Christian Scripture that God wrote to instruct us. As Paul tells Timothy, these “sacred writings . . . are able to make you wise for salvation through faith in Christ Jesus,” and it is this “Scripture” that is “profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness” (2 Tim. 3:16). Old in OT does not mean unimportant or insignificant, and we should approach the text accordingly.

2. Interpret the Old Testament with the same care you would the New Testament.

To give the same care to the OT as to the NT means that we treat it as the very word of God (Mark 7:13; Mark 12:36), which Jesus considered authoritative (Matt. 4:3–4, 7, 10; Matt. 23:1–3), believed could not be broken (John 10:35), and called people to know so as to guard against doctrinal error and hell (Mark 12:24; Luke 16:28–31; Luke 24:25; John 5:46–47). Methodologically, caring for the OT means that we establish the text, make careful observations, consider the context, determine the meaning, and make relevant applications. We consider genre, literary boundaries, grammar, translation, structure, argument flow, key words and concepts, historical and literary contexts, and biblical, systematic, and practical theology.1 We study each passage within its given book (close context), within salvation history (continuing context), and in relationship to Christ and the rest of Scripture (complete context).

Many Christians will give years to understanding Mark and Romans and only weeks to Genesis, Psalms, and Isaiah, while rarely even touching the other books. When others take account of your life and ministry, may such realities not be said of you. We must consider how the OT bears witness about Christ (John 5:39; cf. Luke 24:25–26, 45–47) and faithfully proclaim “the whole counsel of God” (Acts 20:27), ever doing so as those rightly handling “the word of truth” (2 Tim. 2:15).

3. Treat properly the covenantal nature of the Old Testament.